Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Electron configuration

View on Wikipedia

In atomic physics and quantum chemistry, the electron configuration is the distribution of electrons of an atom or molecule (or other physical structure) in atomic or molecular orbitals.[1] For example, the electron configuration of the neon atom is 1s2 2s2 2p6, meaning that the 1s, 2s, and 2p subshells are occupied by two, two, and six electrons, respectively.

Electronic configurations describe each electron as moving independently in an orbital, in an average field created by the nuclei and all the other electrons. Mathematically, configurations are described by Slater determinants or configuration state functions.

According to the laws of quantum mechanics, a level of energy is associated with each electron configuration. In certain conditions, electrons are able to move from one configuration to another by the emission or absorption of a quantum of energy, in the form of a photon.

Knowledge of the electron configuration of different atoms is useful in understanding the structure of the periodic table of elements, for describing the chemical bonds that hold atoms together, and in understanding the chemical formulas of compounds and the geometries of molecules. In bulk materials, this same idea helps explain the peculiar properties of lasers and semiconductors.

Shells and subshells

[edit]| s (l = 0) | p (l = 1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| m = 0 | m = 0 | m = ±1 | ||

| s | pz | px | py | |

| n = 1 | ||||

| n = 2 | ||||

Electron configuration was first conceived under the Bohr model of the atom, and it is still common to speak of shells and subshells despite the advances in understanding of the quantum-mechanical nature of electrons.

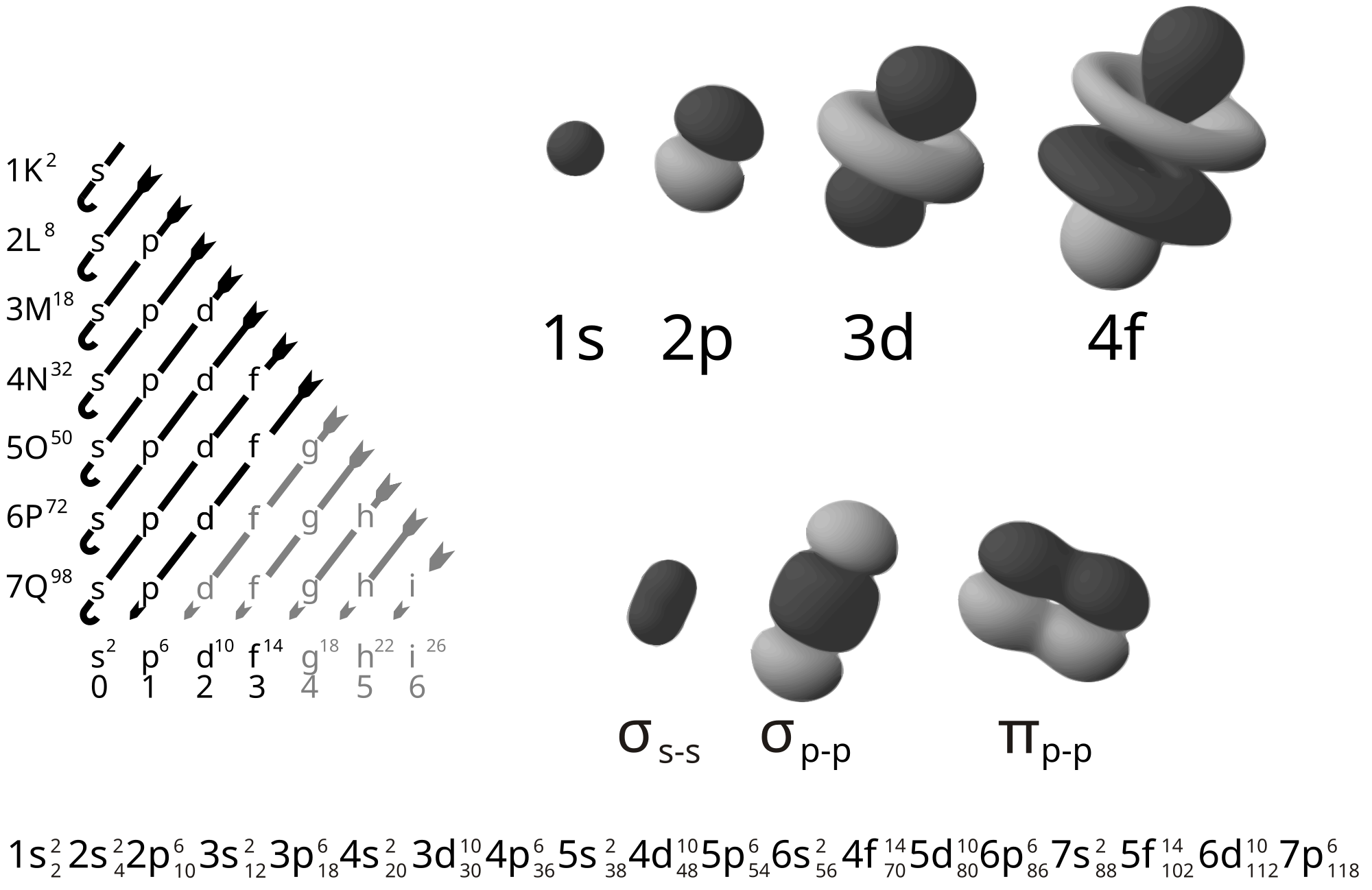

An electron shell is the set of allowed states that share the same principal quantum number, n, that electrons may occupy. In each term of an electron configuration, n is the positive integer that precedes each orbital letter (e.g. helium's electron configuration is 1s2, therefore n = 1, and the orbital contains two electrons). An atom's nth electron shell can accommodate 2n2 electrons. For example, the first shell can accommodate two electrons, the second shell eight electrons, the third shell eighteen, and so on. The factor of two arises because the number of allowed states doubles with each successive shell due to electron spin—each atomic orbital admits up to two otherwise identical electrons with opposite spin, one with a spin +1⁄2 (usually denoted by an up-arrow) and one with a spin of −1⁄2 (with a down-arrow).

A subshell is the set of states defined by a common azimuthal quantum number, l, within a shell. The value of l is in the range from 0 to n − 1. The values l = 0, 1, 2, 3 correspond to the s, p, d, and f labels, respectively. For example, the 3d subshell has n = 3 and l = 2. The maximum number of electrons that can be placed in a subshell is given by 2(2l + 1). This gives two electrons in an s subshell, six electrons in a p subshell, and ten electrons in a d subshell.

The numbers of electrons that can occupy each shell and each subshell arise from the equations of quantum mechanics,[a] in particular the Pauli exclusion principle, which states that no two electrons in the same atom can have the same values of the four quantum numbers.[2]

Exhaustive technical details about the complete quantum mechanical theory of atomic spectra and structure can be found and studied in the basic book of Robert D. Cowan.[3]

Notation

[edit]Physicists and chemists use a standard notation to indicate the electron configurations of atoms and molecules. For atoms, the notation consists of a sequence of atomic subshell labels (e.g. for phosphorus the sequence 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p) with the number of electrons assigned to each subshell placed as a superscript. For example, hydrogen has one electron in the s-orbital of the first shell, so its configuration is written 1s1. Lithium has two electrons in the 1s-subshell and one in the (higher-energy) 2s-subshell, so its configuration is written 1s2 2s1 (pronounced "one-s-two, two-s-one"). Phosphorus (atomic number 15) is as follows: 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p3.

For atoms with many electrons, this notation can become lengthy and so an abbreviated notation is used. The electron configuration can be visualized as the core electrons, equivalent to the noble gas of the preceding period, and the valence electrons: each element in a period differs only by the last few subshells. Phosphorus, for instance, is in the third period. It differs from the second-period neon, whose configuration is 1s2 2s2 2p6, only by the presence of a third shell. The portion of its configuration that is equivalent to neon is abbreviated as [Ne], allowing the configuration of phosphorus to be written as [Ne] 3s2 3p3 rather than writing out the details of the configuration of neon explicitly. This convention is useful as it is the electrons in the outermost shell that most determine the chemistry of the element.

For a given configuration, the order of writing the orbitals is not completely fixed since only the orbital occupancies have physical significance. For example, the electron configuration of the titanium ground state can be written as either [Ar] 4s2 3d2 or [Ar] 3d2 4s2. The first notation follows the order based on the Madelung rule for the configurations of neutral atoms; 4s is filled before 3d in the sequence Ar, K, Ca, Sc, Ti. The second notation groups all orbitals with the same value of n together, corresponding to the "spectroscopic" order of orbital energies that is the reverse of the order in which electrons are removed from a given atom to form positive ions; 3d is filled before 4s in the sequence Ti4+, Ti3+, Ti2+, Ti+, Ti.

The superscript 1 for a singly occupied subshell is not compulsory; for example aluminium may be written as either [Ne] 3s2 3p1 or [Ne] 3s2 3p. In atoms where a subshell is unoccupied despite higher subshells being occupied (as is the case in some ions, as well as certain neutral atoms shown to deviate from the Madelung rule), the empty subshell is either denoted with a superscript 0 or left out altogether. For example, neutral palladium may be written as either [Kr] 4d10 5s0 or simply [Kr] 4d10, and the lanthanum(III) ion may be written as either [Xe] 4f0 or simply [Xe].[4]

It is quite common to see the letters of the orbital labels (s, p, d, f) written in an italic or slanting typeface, although the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) recommends a normal typeface (as used here). The choice of letters originates from a now-obsolete system of categorizing spectral lines as "sharp", "principal", "diffuse" and "fundamental" (or "fine"), based on their observed fine structure: their modern usage indicates orbitals with an azimuthal quantum number, l, of 0, 1, 2 or 3 respectively. After f, the sequence continues alphabetically g, h, i... (l = 4, 5, 6...), skipping j, although orbitals of these types are rarely required.[5][6]

The electron configurations of molecules are written in a similar way, except that molecular orbital labels are used instead of atomic orbital labels (see below).

Energy of ground state and excited states

[edit]The energy associated to an electron is that of its orbital. The energy of a configuration is often approximated as the sum of the energy of each electron, neglecting the electron-electron interactions. The configuration that corresponds to the lowest electronic energy is called the ground state. Any other configuration is an excited state.

As an example, the ground state configuration of the sodium atom is 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s1, as deduced from the Aufbau principle (see below). The first excited state is obtained by promoting a 3s electron to the 3p subshell, to obtain the 1s2 2s2 2p6 3p1 configuration, abbreviated as the 3p level. Atoms can move from one configuration to another by absorbing or emitting energy. In a sodium-vapor lamp for example, sodium atoms are excited to the 3p level by an electrical discharge, and return to the ground state by emitting yellow light of wavelength 589 nm.

Usually, the excitation of valence electrons (such as 3s for sodium) involves energies corresponding to photons of visible or ultraviolet light. The excitation of core electrons is possible, but requires much higher energies, generally corresponding to X-ray photons. This would be the case for example to excite a 2p electron of sodium to the 3s level and form the excited 1s2 2s2 2p5 3s2 configuration.

The remainder of this article deals only with the ground-state configuration, often referred to as "the" configuration of an atom or molecule.

History

[edit]Irving Langmuir was the first to propose in his 1919 article "The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules" in which, building on Gilbert N. Lewis's cubical atom theory and Walther Kossel's chemical bonding theory, he outlined his "concentric theory of atomic structure".[7] Langmuir had developed his work on electron atomic structure from other chemists as is shown in the development of the History of the periodic table and the Octet rule.

Niels Bohr (1923) incorporated Langmuir's model that the periodicity in the properties of the elements might be explained by the electronic structure of the atom.[8] His proposals were based on the then current Bohr model of the atom, in which the electron shells were orbits at a fixed distance from the nucleus. Bohr's original configurations would seem strange to a present-day chemist: sulfur was given as 2.4.4.6 instead of 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p4 (2.8.6). Bohr used 4 and 6 following Alfred Werner's 1893 paper. In fact, the chemists accepted the concept of atoms long before the physicists. Langmuir began his paper referenced above by saying,

«…The problem of the structure of atoms has been attacked mainly by physicists who have given little consideration to the chemical properties which must ultimately be explained by a theory of atomic structure. The vast store of knowledge of chemical properties and relationships, such as is summarized by the Periodic Table, should serve as a better foundation for a theory of atomic structure than the relatively meager experimental data along purely physical lines... These electrons arrange themselves in a series of concentric shells, the first shell containing two electrons, while all other shells tend to hold eight.…»

The valence electrons in the atom were described by Richard Abegg in 1904.[9]

In 1924, E. C. Stoner incorporated Sommerfeld's third quantum number into the description of electron shells, and correctly predicted the shell structure of sulfur to be 2.8.6.[10] However neither Bohr's system nor Stoner's could correctly describe the changes in atomic spectra in a magnetic field (the Zeeman effect).

Bohr was well aware of this shortcoming (and others), and had written to his friend Wolfgang Pauli in 1923 to ask for his help in saving quantum theory (the system now known as "old quantum theory"). Pauli hypothesized successfully that the Zeeman effect can be explained as depending only on the response of the outermost (i.e., valence) electrons of the atom. Pauli was able to reproduce Stoner's shell structure, but with the correct structure of subshells, by his inclusion of a fourth quantum number and his exclusion principle (1925):[11]

It should be forbidden for more than one electron with the same value of the main quantum number n to have the same value for the other three quantum numbers k [l], j [ml] and m [ms].

The Schrödinger equation, published in 1926, gave three of the four quantum numbers as a direct consequence of its solution for the hydrogen atom:[a] this solution yields the atomic orbitals that are shown today in textbooks of chemistry (and above). The examination of atomic spectra allowed the electron configurations of atoms to be determined experimentally, and led to an empirical rule (known as Madelung's rule (1936),[12] see below) for the order in which atomic orbitals are filled with electrons.

Atoms: Aufbau principle and Madelung rule

[edit]The aufbau principle (from the German Aufbau, "building up, construction") was an important part of Bohr's original concept of electron configuration. It may be stated as:[13]

- a maximum of two electrons are put into orbitals in the order of increasing orbital energy: the lowest-energy subshells are filled before electrons are placed in higher-energy orbitals.

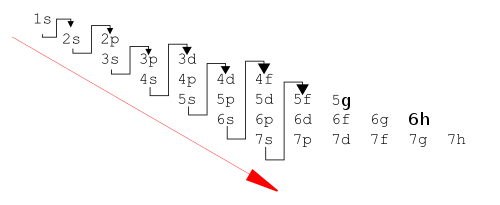

The principle works very well (for the ground states of the atoms) for the known 118 elements, although it is sometimes slightly wrong. The modern form of the aufbau principle describes an order of orbital energies given by Madelung's rule (or Klechkowski's rule). This rule was first stated by Charles Janet in 1929, rediscovered by Erwin Madelung in 1936,[12] and later given a theoretical justification by V. M. Klechkowski:[14]

- Subshells are filled in the order of increasing n + l.

- Where two subshells have the same value of n + l, they are filled in order of increasing n.

This gives the following order for filling the orbitals:

- 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, 5p, 6s, 4f, 5d, 6p, 7s, 5f, 6d, 7p, (8s, 5g, 6f, 7d, 8p, and 9s)

In this list the subshells in parentheses are not occupied in the ground state of the heaviest atom now known (Og, Z = 118).

The aufbau principle can be applied, in a modified form, to the protons and neutrons in the atomic nucleus, as in the shell model of nuclear physics and nuclear chemistry.

Periodic table

[edit]

The form of the periodic table is closely related to the atomic electron configuration for each element. For example, all the elements of group 2 (the table's second column) have an electron configuration of [E] ns2 (where [E] is a noble gas configuration), and have notable similarities in their chemical properties. The periodicity of the periodic table in terms of periodic table blocks is due to the number of electrons (2, 6, 10, and 14) needed to fill s, p, d, and f subshells. These blocks appear as the rectangular sections of the periodic table. The single exception is helium, which despite being an s-block atom is conventionally placed with the other noble gasses in the p-block due to its chemical inertness, a consequence of its full outer shell (though there is discussion in the contemporary literature on whether this exception should be retained).

The electrons in the valence (outermost) shell largely determine each element's chemical properties. The similarities in the chemical properties were remarked on more than a century before the idea of electron configuration.[b]

Shortcomings of the aufbau principle

[edit]The aufbau principle rests on a fundamental postulate that the order of orbital energies is fixed, both for a given element and between different elements; in both cases this is only approximately true. It considers atomic orbitals as "boxes" of fixed energy into which can be placed two electrons and no more. However, the energy of an electron "in" an atomic orbital depends on the energies of all the other electrons of the atom (or ion, or molecule, etc.). There are no "one-electron solutions" for systems of more than one electron, only a set of many-electron solutions that cannot be calculated exactly[c] (although there are mathematical approximations available, such as the Hartree–Fock method).

The fact that the aufbau principle is based on an approximation can be seen from the fact that there is an almost-fixed filling order at all, that, within a given shell, the s-orbital is always filled before the p-orbitals. In a hydrogen-like atom, which only has one electron, the s-orbital and the p-orbitals of the same shell have exactly the same energy, to a very good approximation in the absence of external electromagnetic fields. (However, in a real hydrogen atom, the energy levels are slightly split by the magnetic field of the nucleus, and by the quantum electrodynamic effects of the Lamb shift.)

Ionization of the transition metals

[edit]The naïve application of the aufbau principle leads to a well-known paradox (or apparent paradox) in the basic chemistry of the transition metals. Potassium and calcium appear in the periodic table before the transition metals, and have electron configurations [Ar] 4s1 and [Ar] 4s2 respectively, i.e. the 4s-orbital is filled before the 3d-orbital. This is in line with Madelung's rule, as the 4s-orbital has n + l = 4 (n = 4, l = 0) while the 3d-orbital has n + l = 5 (n = 3, l = 2). After calcium, most neutral atoms in the first series of transition metals (scandium through zinc) have configurations with two 4s electrons, but there are two exceptions. Chromium and copper have electron configurations [Ar] 3d5 4s1 and [Ar] 3d10 4s1 respectively, i.e. one electron has passed from the 4s-orbital to a 3d-orbital to generate a half-filled or filled subshell. In this case, the usual explanation is that "half-filled or completely filled subshells are particularly stable arrangements of electrons". However, this is not supported by the facts, as tungsten (W) has a Madelung-following d4 s2 configuration and not d5 s1, and niobium (Nb) has an anomalous d4 s1 configuration that does not give it a half-filled or completely filled subshell.[15]

The apparent paradox arises when electrons are removed from the transition metal atoms to form ions. The first electrons to be ionized come not from the 3d-orbital, as one would expect if it were "higher in energy", but from the 4s-orbital. This interchange of electrons between 4s and 3d is found for all atoms of the first series of transition metals.[d] The configurations of the neutral atoms (K, Ca, Sc, Ti, V, Cr, ...) usually follow the order 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, ...; however the successive stages of ionization of a given atom (such as Fe4+, Fe3+, Fe2+, Fe+, Fe) usually follow the order 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 3d, 4s, ...

This phenomenon is only paradoxical if it is assumed that the energy order of atomic orbitals is fixed and unaffected by the nuclear charge or by the presence of electrons in other orbitals. If that were the case, the 3d-orbital would have the same energy as the 3p-orbital, as it does in hydrogen, yet it clearly does not. There is no special reason why the Fe2+ ion should have the same electron configuration as the chromium atom, given that iron has two more protons in its nucleus than chromium, and that the chemistry of the two species is very different. Melrose and Eric Scerri have analyzed the changes of orbital energy with orbital occupations in terms of the two-electron repulsion integrals of the Hartree–Fock method of atomic structure calculation.[16] More recently Scerri has argued that contrary to what is stated in the vast majority of sources including the title of his previous article on the subject, 3d orbitals rather than 4s are in fact preferentially occupied.[17]

In chemical environments, configurations can change even more: Th3+ as a bare ion has a configuration of [Rn] 5f1, yet in most ThIII compounds the thorium atom has a 6d1 configuration instead.[18][19] Mostly, what is present is rather a superposition of various configurations.[15] For instance, copper metal is poorly described by either an [Ar] 3d10 4s1 or an [Ar] 3d9 4s2 configuration, but is rather well described as a 90% contribution of the first and a 10% contribution of the second. Indeed, visible light is already enough to excite electrons in most transition metals, and they often continuously "flow" through different configurations when that happens (copper and its group are an exception).[20]

Similar ion-like 3dx 4s0 configurations occur in transition metal complexes as described by the simple crystal field theory, even if the metal has oxidation state 0. For example, chromium hexacarbonyl can be described as a chromium atom (not ion) surrounded by six carbon monoxide ligands. The electron configuration of the central chromium atom is described as 3d6 with the six electrons filling the three lower-energy d orbitals between the ligands. The other two d orbitals are at higher energy due to the crystal field of the ligands. This picture is consistent with the experimental fact that the complex is diamagnetic, meaning that it has no unpaired electrons. However, in a more accurate description using molecular orbital theory, the d-like orbitals occupied by the six electrons are no longer identical with the d orbitals of the free atom.

Other exceptions to Madelung's rule

[edit]There are several more exceptions to Madelung's rule among the heavier elements, and as atomic number increases it becomes more and more difficult to find simple explanations such as the stability of half-filled subshells. It is possible to predict most of the exceptions by Hartree–Fock calculations,[21] which are an approximate method for taking account of the effect of the other electrons on orbital energies. Qualitatively, for example, the 4d elements have the greatest concentration of Madelung anomalies, because the 4d–5s gap is larger than the 3d–4s and 5d–6s gaps.[22]

For the heavier elements, it is also necessary to take account of the effects of special relativity on the energies of the atomic orbitals, as the inner-shell electrons are moving at speeds approaching the speed of light. In general, these relativistic effects[23] tend to decrease the energy of the s-orbitals in relation to the other atomic orbitals.[24] This is the reason why the 6d elements are predicted to have no Madelung anomalies apart from lawrencium (for which relativistic effects stabilise the p1/2 orbital as well and cause its occupancy in the ground state), as relativity intervenes to make the 7s orbitals lower in energy than the 6d ones.

The table below shows the configurations of the f-block (green) and d-block (blue) atoms. It shows the ground state configuration in terms of orbital occupancy, but it does not show the ground state in terms of the sequence of orbital energies as determined spectroscopically. For example, in the transition metals, the 4s orbital is of a higher energy than the 3d orbitals; and in the lanthanides, the 6s is higher than the 4f and 5d. The ground states can be seen in the Electron configurations of the elements (data page). However this also depends on the charge: a calcium atom has 4s lower in energy than 3d, but a Ca2+ cation has 3d lower in energy than 4s. In practice the configurations predicted by the Madelung rule are at least close to the ground state even in these anomalous cases.[25] The empty f orbitals in lanthanum, actinium, and thorium contribute to chemical bonding,[26][27] as do the empty p orbitals in transition metals.[28]

Vacant s, d, and f orbitals have been shown explicitly, as is occasionally done,[29] to emphasise the filling order and to clarify that even orbitals unoccupied in the ground state (e.g. lanthanum 4f or palladium 5s) may be occupied and bonding in chemical compounds. (The same is also true for the p-orbitals, which are not explicitly shown because they are only actually occupied for lawrencium in gas-phase ground states.)

| Period 4 | Period 5 | Period 6 | Period 7 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | Z | Electron Configuration | Element | Z | Electron Configuration | Element | Z | Electron Configuration | Element | Z | Electron Configuration | |||

| Lanthanum | 57 | [Xe] 6s2 4f0 5d1 | Actinium | 89 | [Rn] 7s2 5f0 6d1 | |||||||||

| Cerium | 58 | [Xe] 6s2 4f1 5d1 | Thorium | 90 | [Rn] 7s2 5f0 6d2 | |||||||||

| Praseodymium | 59 | [Xe] 6s2 4f3 5d0 | Protactinium | 91 | [Rn] 7s2 5f2 6d1 | |||||||||

| Neodymium | 60 | [Xe] 6s2 4f4 5d0 | Uranium | 92 | [Rn] 7s2 5f3 6d1 | |||||||||

| Promethium | 61 | [Xe] 6s2 4f5 5d0 | Neptunium | 93 | [Rn] 7s2 5f4 6d1 | |||||||||

| Samarium | 62 | [Xe] 6s2 4f6 5d0 | Plutonium | 94 | [Rn] 7s2 5f6 6d0 | |||||||||

| Europium | 63 | [Xe] 6s2 4f7 5d0 | Americium | 95 | [Rn] 7s2 5f7 6d0 | |||||||||

| Gadolinium | 64 | [Xe] 6s2 4f7 5d1 | Curium | 96 | [Rn] 7s2 5f7 6d1 | |||||||||

| Terbium | 65 | [Xe] 6s2 4f9 5d0 | Berkelium | 97 | [Rn] 7s2 5f9 6d0 | |||||||||

| Dysprosium | 66 | [Xe] 6s2 4f10 5d0 | Californium | 98 | [Rn] 7s2 5f10 6d0 | |||||||||

| Holmium | 67 | [Xe] 6s2 4f11 5d0 | Einsteinium | 99 | [Rn] 7s2 5f11 6d0 | |||||||||

| Erbium | 68 | [Xe] 6s2 4f12 5d0 | Fermium | 100 | [Rn] 7s2 5f12 6d0 | |||||||||

| Thulium | 69 | [Xe] 6s2 4f13 5d0 | Mendelevium | 101 | [Rn] 7s2 5f13 6d0 | |||||||||

| Ytterbium | 70 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d0 | Nobelium | 102 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d0 | |||||||||

| Scandium | 21 | [Ar] 4s2 3d1 | Yttrium | 39 | [Kr] 5s2 4d1 | Lutetium | 71 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d1 | Lawrencium | 103 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d0 7p1 | |||

| Titanium | 22 | [Ar] 4s2 3d2 | Zirconium | 40 | [Kr] 5s2 4d2 | Hafnium | 72 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d2 | Rutherfordium | 104 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d2 | |||

| Vanadium | 23 | [Ar] 4s2 3d3 | Niobium | 41 | [Kr] 5s1 4d4 | Tantalum | 73 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d3 | Dubnium | 105 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d3 | |||

| Chromium | 24 | [Ar] 4s1 3d5 | Molybdenum | 42 | [Kr] 5s1 4d5 | Tungsten | 74 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d4 | Seaborgium | 106 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d4 | |||

| Manganese | 25 | [Ar] 4s2 3d5 | Technetium | 43 | [Kr] 5s2 4d5 | Rhenium | 75 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d5 | Bohrium | 107 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d5 | |||

| Iron | 26 | [Ar] 4s2 3d6 | Ruthenium | 44 | [Kr] 5s1 4d7 | Osmium | 76 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d6 | Hassium | 108 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d6 | |||

| Cobalt | 27 | [Ar] 4s2 3d7 | Rhodium | 45 | [Kr] 5s1 4d8 | Iridium | 77 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d7 | Meitnerium | 109 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d7 | |||

| Nickel | 28 | [Ar] 4s2 3d8 or [Ar] 4s1 3d9 (disputed)[32] |

Palladium | 46 | [Kr] 5s0 4d10 | Platinum | 78 | [Xe] 6s1 4f14 5d9 | Darmstadtium | 110 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d8 | |||

| Copper | 29 | [Ar] 4s1 3d10 | Silver | 47 | [Kr] 5s1 4d10 | Gold | 79 | [Xe] 6s1 4f14 5d10 | Roentgenium | 111 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d9 | |||

| Zinc | 30 | [Ar] 4s2 3d10 | Cadmium | 48 | [Kr] 5s2 4d10 | Mercury | 80 | [Xe] 6s2 4f14 5d10 | Copernicium | 112 | [Rn] 7s2 5f14 6d10 | |||

The various anomalies describe the free atoms and do not necessarily predict chemical behavior. Thus for example neodymium typically forms the +3 oxidation state, despite its configuration [Xe] 4f4 5d0 6s2 that if interpreted naïvely would suggest a more stable +2 oxidation state corresponding to losing only the 6s electrons. Contrariwise, uranium as [Rn] 5f3 6d1 7s2 is not very stable in the +3 oxidation state either, preferring +4 and +6.[33]

The electron-shell configuration of elements beyond hassium has not yet been empirically verified, but they are expected to follow Madelung's rule without exceptions until element 120. Element 121 should have the anomalous configuration [Og] 8s2 5g0 6f0 7d0 8p1, having a p rather than a g electron. Electron configurations beyond this are tentative and predictions differ between models,[34] but Madelung's rule is expected to break down due to the closeness in energy of the 5g, 6f, 7d, and 8p1/2 orbitals.[31] That said, the filling sequence 8s, 5g, 6f, 7d, 8p is predicted to hold approximately, with perturbations due to the huge spin-orbit splitting of the 8p and 9p shells, and the huge relativistic stabilisation of the 9s shell.[35]

Open and closed shells

[edit]In the context of atomic orbitals, an open shell is a valence shell which is not completely filled with electrons or that has not given all of its valence electrons through chemical bonds with other atoms or molecules during a chemical reaction. Conversely a closed shell is obtained with a completely filled valence shell. This configuration is very stable.[36]

For molecules, "open shell" signifies that there are unpaired electrons. In molecular orbital theory, this leads to molecular orbitals that are singly occupied. In computational chemistry implementations of molecular orbital theory, open-shell molecules have to be handled by either the restricted open-shell Hartree–Fock method or the unrestricted Hartree–Fock method. Conversely a closed-shell configuration corresponds to a state where all molecular orbitals are either doubly occupied or empty (a singlet state).[37] Open shell molecules are more difficult to study computationally.[38]

Noble gas configuration

[edit]Noble gas configuration is the electron configuration of noble gases. The basis of all chemical reactions is the tendency of chemical elements to acquire stability. Main-group atoms generally obey the octet rule, while transition metals generally obey the 18-electron rule. The noble gases (He, Ne, Ar, Kr, Xe, Rn) are less reactive than other elements because they already have a noble gas configuration. Oganesson is predicted to be more reactive due to relativistic effects for heavy atoms.

Period Element Configuration 1 He 1s2 2 Ne 1s2 2s2 2p6 3 Ar 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4 Kr 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p6 5 Xe 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p6 5s2 4d10 5p6 6 Rn 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p6 5s2 4d10 5p6 6s2 4f14 5d10 6p6 7 Og 1s2 2s2 2p6 3s2 3p6 4s2 3d10 4p6 5s2 4d10 5p6 6s2 4f14 5d10 6p6 7s2 5f14 6d10 7p6

Every system has the tendency to acquire the state of stability or a state of minimum energy, and so chemical elements take part in chemical reactions to acquire a stable electronic configuration similar to that of its nearest noble gas. An example of this tendency is two hydrogen (H) atoms reacting with one oxygen (O) atom to form water (H2O). Neutral atomic hydrogen has one electron in its valence shell, and on formation of water it acquires a share of a second electron coming from oxygen, so that its configuration is similar to that of its nearest noble gas helium (He) with two electrons in its valence shell. Similarly, neutral atomic oxygen has six electrons in its valence shell, and acquires a share of two electrons from the two hydrogen atoms, so that its configuration is similar to that of its nearest noble gas neon with eight electrons in its valence shell.

Electron configuration in molecules

[edit]Electron configuration in molecules is more complex than the electron configuration of atoms, as each molecule has a different orbital structure. The molecular orbitals are labelled according to their symmetry,[e] rather than the atomic orbital labels used for atoms and monatomic ions; hence, the electron configuration of the dioxygen molecule, O2, is written 1σg2 1σu2 2σg2 2σu2 3σg2 1πu4 1πg2,[39][40] or equivalently 1σg2 1σu2 2σg2 2σu2 1πu4 3σg2 1πg2.[1] The term 1πg2 represents the two electrons in the two degenerate π*-orbitals (antibonding). From Hund's rules, these electrons have parallel spins in the ground state, and so dioxygen has a net magnetic moment (it is paramagnetic). The explanation of the paramagnetism of dioxygen was a major success for molecular orbital theory.

The electronic configuration of polyatomic molecules can change without absorption or emission of a photon through vibronic couplings.

Electron configuration in solids

[edit]In a solid, the electron states become very numerous. They cease to be discrete, and effectively blend into continuous ranges of possible states (an electron band). The notion of electron configuration ceases to be relevant, and yields to band theory.

Applications

[edit]The most widespread application of electron configurations is in the rationalization of chemical properties, in both inorganic and organic chemistry. In effect, electron configurations, along with some simplified forms of molecular orbital theory, have become the modern equivalent of the valence concept, describing the number and type of chemical bonds that an atom can be expected to form.

This approach is taken further in computational chemistry, which typically attempts to make quantitative estimates of chemical properties. For many years, most such calculations relied upon the "linear combination of atomic orbitals" (LCAO) approximation, using an ever-larger and more complex basis set of atomic orbitals as the starting point. The last step in such a calculation is the assignment of electrons among the molecular orbitals according to the aufbau principle. Not all methods in computational chemistry rely on electron configuration: density functional theory (DFT) is an important example of a method that discards the model.

For atoms or molecules with more than one electron, the motion of electrons are correlated and such a picture is no longer exact. A very large number of electronic configurations are needed to exactly describe any multi-electron system, and precisely associating a certain energy level with any single configuration is not possible. However, the electronic wave function is usually dominated by a very small number of configurations and therefore the notion of electronic configuration remains essential for multi-electron systems.

A fundamental application of electron configurations is in the interpretation of atomic spectra. In this case, it is necessary to supplement the electron configuration with one or more term symbols, which describe the different energy levels available to an atom. Term symbols can be calculated for any electron configuration, not just the ground-state configuration listed in tables, although not all the energy levels are observed in practice. It is through the analysis of atomic spectra that the ground-state electron configurations of the elements were experimentally determined.

See also

[edit]- Born–Oppenheimer approximation

- d electron count

- Electron configurations of the elements (data page)

- Extended periodic table – discusses the limits of the periodic table

- Group (periodic table)

- HOMO/LUMO

- Molecular term symbol

- Octet rule

- Periodic table (electron configurations)

- Spherical harmonics

- Unpaired electron

- Valence shell

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b In formal terms, the quantum numbers n, l and ml arise from the fact that the solutions to the time-independent Schrödinger equation for hydrogen-like atoms are based on spherical harmonics.

- ^ The similarities in chemical properties and the numerical relationship between the atomic weights of calcium, strontium and barium was first noted by Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner in 1817.

- ^ Electrons are identical particles, a fact that is sometimes referred to as "indistinguishability of electrons". A one-electron solution to a many-electron system would imply that the electrons could be distinguished from one another, and there is strong experimental evidence that they can't be. The exact solution of a many-electron system is a n-body problem with n ≥ 3 (the nucleus counts as one of the "bodies"): such problems have evaded analytical solution since at least the time of Euler.

- ^ There are some cases in the second and third series where the electron remains in an s-orbital.

- ^ The labels are written in lowercase to indicate that they correspond to one-electron functions. They are numbered consecutively for each symmetry type (irreducible representation in the character table of the point group for the molecule), starting from the orbital of lowest energy for that type.

References

[edit]- ^ a b IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "configuration (electronic)". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01248

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "Pauli exclusion principle". doi:10.1351/goldbook.PT07089

- ^ Cowan, Robert D. (2020). The Theory of Atomic Structure and Spectra. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520906150.

- ^ Rayner-Canham, Geoff; Overton, Tina (2014). Descriptive Inorganic Chemistry (6 ed.). Macmillan Education. pp. 13–15. ISBN 978-1-319-15411-0.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. (2007). "Electron Orbital". wolfram.

- ^ Ebbing, Darrell D.; Gammon, Steven D. (12 January 2007). General Chemistry. Cengage Learning. p. 284. ISBN 978-0-618-73879-3.

- ^ Langmuir, Irving (June 1919). "The Arrangement of Electrons in Atoms and Molecules". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 41 (6): 868–934. Bibcode:1919JAChS..41..868L. doi:10.1021/ja02227a002.

- ^ Bohr, Niels (1923). "Über die Anwendung der Quantumtheorie auf den Atombau. I". Zeitschrift für Physik. 13 (1): 117. Bibcode:1923ZPhy...13..117B. doi:10.1007/BF01328209. S2CID 123582460.

- ^ Abegg, R. (1904). "Die Valenz und das periodische System. Versuch einer Theorie der Molekularverbindungen" [Valency and the periodic system. Attempt at a theory of molecular compounds]. Zeitschrift für Anorganische Chemie. 39 (1): 330–380. doi:10.1002/zaac.19040390125.

- ^ Stoner, E.C. (1924). "The distribution of electrons among atomic levels". Philosophical Magazine. 6th Series. 48 (286): 719–36. doi:10.1080/14786442408634535.

- ^ Pauli, Wolfgang (1925). "Über den Einfluss der Geschwindigkeitsabhändigkeit der elektronmasse auf den Zeemaneffekt". Zeitschrift für Physik. 31 (1): 373. Bibcode:1925ZPhy...31..373P. doi:10.1007/BF02980592. S2CID 122477612. English translation from Scerri, Eric R. (1991). "The Electron Configuration Model, Quantum Mechanics and Reduction" (PDF). The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science. 42 (3): 309–25. doi:10.1093/bjps/42.3.309.

- ^ a b Madelung, Erwin (1936). Mathematische Hilfsmittel des Physikers. Berlin: Springer.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "aufbau principle". doi:10.1351/goldbook.AT06996

- ^ Wong, D. Pan (1979). "Theoretical justification of Madelung's rule". Journal of Chemical Education. 56 (11): 714–18. Bibcode:1979JChEd..56..714W. doi:10.1021/ed056p714.

- ^ a b Scerri, Eric (2019). "Five ideas in chemical education that must die". Foundations of Chemistry. 21: 61–69. doi:10.1007/s10698-018-09327-y. S2CID 104311030.

- ^ Melrose, Melvyn P.; Scerri, Eric R. (1996). "Why the 4s Orbital is Occupied before the 3d". Journal of Chemical Education. 73 (6): 498–503. Bibcode:1996JChEd..73..498M. doi:10.1021/ed073p498.

- ^ Scerri, Eric (7 November 2013). "The trouble with the aufbau principle". Education in Chemistry. Vol. 50, no. 6. Royal Society of Chemistry. pp. 24–26. Archived from the original on 21 January 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2018.

- ^ Langeslay, Ryan R.; Fieser, Megan E.; Ziller, Joseph W.; Furche, Philip; Evans, William J. (2015). "Synthesis, structure, and reactivity of crystalline molecular complexes of the {[C5H3(SiMe3)2]3Th}1− anion containing thorium in the formal +2 oxidation state". Chem. Sci. 6 (1): 517–521. doi:10.1039/C4SC03033H. PMC 5811171. PMID 29560172.

- ^ Wickleder, Mathias S.; Fourest, Blandine; Dorhout, Peter K. (2006). "Thorium". In Morss, Lester R.; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (PDF). Vol. 3 (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, the Netherlands: Springer. pp. 52–160. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3598-5_3. ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016.

- ^ Ferrão, Luiz; Machado, Francisco Bolivar Correto; Cunha, Leonardo dos Anjos; Fernandes, Gabriel Freire Sanzovo. "The Chemical Bond Across the Periodic Table: Part 1 – First Row and Simple Metals". ChemRxiv. doi:10.26434/chemrxiv.11860941. S2CID 226121612. Archived from the original on 1 December 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ^ Meek, Terry L.; Allen, Leland C. (2002). "Configuration irregularities: deviations from the Madelung rule and inversion of orbital energy levels". Chemical Physics Letters. 362 (5–6): 362–64. Bibcode:2002CPL...362..362M. doi:10.1016/S0009-2614(02)00919-3.

- ^ Kulsha, Andrey (2004). "Периодическая система химических элементов Д. И. Менделеева" [D. I. Mendeleev's periodic system of the chemical elements] (PDF). primefan.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "relativistic effects". doi:10.1351/goldbook.RT07093

- ^ Pyykkö, Pekka (1988). "Relativistic effects in structural chemistry". Chemical Reviews. 88 (3): 563–94. doi:10.1021/cr00085a006.

- ^ See the NIST tables

- ^ Glotzel, D. (1978). "Ground-state properties of f band metals: lanthanum, cerium and thorium". Journal of Physics F: Metal Physics. 8 (7): L163 – L168. Bibcode:1978JPhF....8L.163G. doi:10.1088/0305-4608/8/7/004.

- ^ Xu, Wei; Ji, Wen-Xin; Qiu, Yi-Xiang; Schwarz, W. H. Eugen; Wang, Shu-Guang (2013). "On structure and bonding of lanthanoid trifluorides LnF3 (Ln = La to Lu)". Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics. 2013 (15): 7839–47. Bibcode:2013PCCP...15.7839X. doi:10.1039/C3CP50717C. PMID 23598823.

- ^ Example for platinum

- ^ See for example this Russian periodic table poster by A. V. Kulsha and T. A. Kolevich

- ^ Miessler, G. L.; Tarr, D. A. (1999). Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall. p. 38.

- ^ a b Hoffman, Darleane C.; Lee, Diana M.; Pershina, Valeria (2006). "Transactinides and the future elements". In Morss; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5.

- ^ Scerri, Eric R. (2007). The periodic table: its story and its significance. Oxford University Press. pp. 239–240. ISBN 978-0-19-530573-9.

- ^ Jørgensen, Christian K. (1988). "Influence of rare earths on chemical understanding and classification". Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths. Vol. 11. pp. 197–292. doi:10.1016/S0168-1273(88)11007-6. ISBN 978-0-444-87080-3.

- ^ Umemoto, Koichiro; Saito, Susumu (1996). "Electronic Configurations of Superheavy Elements". Journal of the Physical Society of Japan. 65 (10): 3175–9. Bibcode:1996JPSJ...65.3175U. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.65.3175. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- ^ Pyykkö, Pekka (2016). Is the Periodic Table all right ("PT OK")? (PDF). Nobel Symposium NS160 – Chemistry and Physics of Heavy and Superheavy Elements.

- ^ "Periodic table". Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 1 November 2007.

- ^ "Chapter 11. Configuration Interaction". AMPAC™ 10 User Guide. Semichem, Inc.

- ^ "Laboratory for Theoretical Studies of Electronic Structure and Spectroscopy of Open-Shell and Electronically Excited Species – iOpenShell". iopenshell.usc.edu.

- ^ Levine I.N. Quantum Chemistry (4th ed., Prentice Hall 1991) p.376 ISBN 0-205-12770-3

- ^ Miessler G.L. and Tarr D.A. Inorganic Chemistry (2nd ed., Prentice Hall 1999) p.118 ISBN 0-13-841891-8

External links

[edit]

Electron configuration

View on GrokipediaBasic Structure

Shells and Subshells

In the quantum mechanical model of the atom, electrons occupy regions of space known as orbitals, which are organized into principal shells and subshells defined by specific quantum numbers. The principal quantum number , which can take any positive integer value (1, 2, 3, ...), specifies the shell and corresponds to the average distance of the electron from the nucleus and its energy level. Shells with higher values are larger in size and possess higher energy; for instance, the innermost shell is designated as K (), followed by L (), M (), and so on, a notation originating from early X-ray spectroscopy.[3][2] Within each shell, subshells are defined by the azimuthal quantum number , which ranges from 0 to and determines the shape of the orbitals. The value of corresponds to subshell designations: for s (spherical symmetry around the nucleus), for p (dumbbell-shaped with two lobes along an axis), for d (cloverleaf or double-dumbbell shapes), and for f (more complex, multi-lobed structures). These shapes arise from the angular part of the wave function in the Schrödinger equation solutions for hydrogen-like atoms.[3][2] Each subshell consists of orbitals oriented in space, specified by the magnetic quantum number , which takes integer values from to , inclusive, yielding possible orientations per subshell (e.g., 3 for p, 5 for d). Electrons within these orbitals also possess an intrinsic spin, described by the spin quantum number or , allowing each orbital to accommodate a maximum of two electrons with opposite spins. Consequently, the maximum number of electrons per subshell is given by , such as 2 for an s subshell and 6 for a p subshell.[3][2] Orbitals are further characterized by nodes, regions where the probability of finding an electron is zero. The total number of nodes in an orbital is , comprising angular nodes (equal to , determined by the angular wave function) and radial nodes (equal to , where the radial probability function crosses zero). For example, a 2p orbital (, ) has one angular node (a nodal plane through the nucleus) and no radial nodes.[4][5]Notation

The electron configuration of an atom or ion is conventionally expressed using spectroscopic notation, where subshells are listed in order of increasing energy, and the number of electrons occupying each subshell is indicated by a superscript numeral following the subshell designation. The subshell symbol consists of the principal quantum number (the shell number) followed by a letter representing the azimuthal quantum number : s for , p for , d for , and f for . For instance, the ground-state electron configuration of neon (atomic number 10) is written as , indicating two electrons in the 1s subshell, two in the 2s subshell, and six in the 2p subshell.[1][6] The order in which subshells are filled follows the Madelung rule, prioritizing those with the lowest sum of ; for subshells with equal , the one with the lower is filled first. This sequence begins with 1s, then 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, and so on, providing a systematic way to construct configurations for elements across the periodic table. To condense lengthy configurations, especially for heavier elements, the inert core of electrons matching the nearest preceding noble gas is abbreviated in square brackets using the noble gas symbol, followed by the valence electron configuration. For example, the configuration of phosphorus (atomic number 15) is shortened to , where represents the filled core./Quantum_Mechanics/10:_Multi-electron_Atoms/Electron_Configuration)[7] For ions, the notation is derived from the neutral atom's configuration by adding or removing electrons according to the ion's charge. Cations are formed by removing electrons from the highest-energy subshells first—typically the outermost s subshell, followed by d if necessary—while anions involve adding electrons to the valence subshell. The iron(II) ion, , for example, starts from neutral iron's and removes the two 4s electrons, yielding . This approach preserves the core while adjusting the valence shell to reflect the ionic state.[8] An alternative to spectroscopic notation is the orbital box diagram, which visually represents the distribution of electrons within subshells using boxes for individual orbitals and arrows for electrons to denote their spin orientation (↑ for spin-up, ↓ for spin-down). Each box holds up to two electrons with opposite spins, per the Pauli exclusion principle, and unpaired electrons in degenerate orbitals align spins parallel to maximize multiplicity, as implied by Hund's rule. For carbon in its ground state, the 2p subshell might be diagrammed as three boxes with single ↑ arrows in two boxes and none in the third, illustrating the two unpaired electrons. This format is particularly useful for highlighting spin and pairing without explicit superscripts.[9] In excited states, the notation remains the same but shows electrons promoted from lower to higher energy orbitals, often violating the ground-state filling order temporarily. For example, an excited configuration of carbon could be , where one 2s electron is excited to the 2p subshell, resulting in three unpaired electrons in 2p. Such representations are common in spectroscopy to describe transient electronic arrangements. For polyatomic species like molecular ions, electron configurations extend atomic notation by specifying orbital symmetries (e.g., σ or π), but the core principles of subshell labeling and electron counting apply analogously.[10]Energy Considerations

Ground State Energies

The ground state of an atom corresponds to the electron configuration that minimizes the total energy of the system, as determined by solutions to the time-independent Schrödinger equation for the multi-electron Hamiltonian. This equation accounts for the kinetic energy of electrons, their attraction to the nucleus, and the repulsive interactions between electrons, but exact analytical solutions are intractable for atoms beyond hydrogen due to the many-body nature of the problem. The ground state wavefunction thus represents the lowest-energy eigenstate, where electrons occupy orbitals in a way that achieves this minimum total energy.[11] In multi-electron atoms, the effective nuclear charge experienced by an electron is reduced from the full nuclear charge by the shielding constant , given by , where quantifies the screening from inner electrons. Slater's rules provide an empirical approximation for by grouping electrons into shells and assigning shielding contributions based on their radial distribution, such as 0.85 for electrons in the same group (except for 1s) and 1.00 for those in inner groups. This effective charge influences orbital energies, with outer electrons feeling a lower attraction due to incomplete shielding by core electrons. Penetration and shielding effects further dictate the relative energies of subshells within a principal quantum number , as electrons in orbitals with higher angular momentum (s < p < d < f) have radial wavefunctions that avoid the nucleus more, experiencing greater shielding and thus higher energies. The penetration ability decreases from s to f orbitals because the probability density near the nucleus diminishes with increasing , leading to the energy ordering for the same . These effects arise from the angular dependence of the orbitals, where s electrons can approach the nucleus closely, reducing their energy relative to higher- subshells.[12] For hydrogen-like atoms (one electron around a nucleus of charge ), the Schrödinger equation yields exact energy levels independent of : where is the principal quantum number; this scales with due to the purely Coulombic potential. In multi-electron atoms, however, electron-electron repulsions cause deviations, splitting energies by and making , so actual ground state energies are higher (less negative) than hydrogenic predictions. For instance, the helium ground state energy is approximately -79 eV, compared to the hydrogenic value of -108.8 eV for .[13] The Hartree-Fock method approximates ground state energies by assuming a single Slater determinant wavefunction, where each electron moves in an average field created by the others, leading to self-consistent orbitals that minimize the energy. This mean-field approach neglects instantaneous correlations but provides energies accurate to within 1-5% of experimental values for light atoms, such as -14.573 hartree for beryllium versus the exact -14.667 hartree. The method solves the resulting integro-differential equations iteratively to obtain the total energy as the expectation value of the Hamiltonian. The variational principle underpins these approximations by stating that for any normalized trial wavefunction , the expectation value provides an upper bound to the true ground state energy , with equality only for the exact ground state. Trial functions incorporating parameters, such as effective in simple products of hydrogenic orbitals, are optimized by minimizing this energy, yielding reliable estimates; for helium, a trial function with variational gives -77.5 eV, close to the Hartree-Fock limit of -77.8 eV. This principle ensures systematic improvement with better trials, guiding computational quantum chemistry.[14]Excited States

In atomic physics, excited states occur when one or more electrons in an atom are promoted from their ground-state orbitals to higher-energy subshells, resulting in a temporary configuration with increased total energy. This promotion typically happens through the absorption of a photon whose energy matches the difference between the initial and final orbital energies, or via inelastic collisions with other particles such as electrons or atoms that transfer sufficient kinetic energy to the target electron.[15] Such excitations are inherently unstable, as the atom seeks to minimize its energy by returning to lower configurations. The energy gaps between ground and excited states vary depending on the orbitals involved; valence electron excitations often span the ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) range (typically 1–10 eV), while core electron promotions require higher energies in the X-ray regime (hundreds of eV to keV). These gaps are precisely measured using spectroscopic techniques: UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy probes valence transitions in light atoms, revealing band structures from molecular-like perturbations in heavier elements, whereas X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) targets inner-shell excitations, providing insights into electronic structure near the nucleus. For instance, in transition metals, UV-Vis spectra show d-orbital excitations around 2–4 eV, corresponding to colors in compounds.[16][17] A classic example is the hydrogen atom, where the ground-state configuration can be excited to by absorbing a photon of approximately 10.2 eV (Lyman-alpha line at 121.6 nm). In this process, the electron jumps from the , orbital to , , altering the atom's overall wavefunction and enabling subsequent emission upon relaxation. This transition exemplifies single-electron promotion in a one-electron system, serving as a benchmark for quantum mechanical models.[18] Excited states have finite lifetimes, typically on the order of nanoseconds for singlet states, after which the electron relaxes to the ground state, emitting a photon in processes like fluorescence (spin-allowed, rapid decay) or phosphorescence (spin-forbidden, slower via intersystem crossing, lasting milliseconds to seconds). Fluorescence lifetimes for atomic excited states, such as the level in alkali metals, are around 10–20 ns, determined by the Einstein A coefficient for spontaneous emission. Phosphorescence involves triplet states and is less common in isolated atoms but observable in gases under low pressure. These relaxation pathways conserve energy and angular momentum, producing characteristic spectral lines.[19][20] Transitions to excited states obey selection rules derived from quantum mechanics, particularly for electric dipole (E1) interactions, which dominate absorption and emission. The primary rule is for the orbital angular momentum quantum number of the transitioning electron, ensuring parity change and non-zero transition dipole moment; additionally, (no spin flip) and (with ) apply for total angular momentum. These rules explain why or transitions are allowed, while or are forbidden in the dipole approximation, though weaker magnetic dipole or electric quadrupole mechanisms can enable them at reduced intensities.[21] In multi-electron atoms, excitations can involve multiple electrons simultaneously, leading to correlated configurations that single-particle models cannot accurately describe. Configuration interaction (CI) methods address this by expanding the wavefunction as a linear combination of multiple Slater determinants from excited configurations, capturing electron correlation effects essential for precise energy calculations. For example, in carbon, the first excited state involves promoting a 2s electron to 2p while mixing with double excitations, yielding energies accurate to within 0.1 eV using full CI approaches. Multi-electron excitations, such as simultaneous 1s and 2p promotions in neon, require non-perturbative treatments to account for shake-up processes observed in X-ray spectra.[22][23][24]Filling Principles

Aufbau Principle and Madelung Rule

The Aufbau principle dictates that, in the ground state of multi-electron atoms, electrons occupy atomic orbitals in a sequence of increasing energy, starting from the lowest available level, to achieve the most stable configuration. This "building-up" process assumes that each successive electron added to an atom fills the orbital with the lowest possible energy, minimizing the total energy of the system. The principle provides a foundational framework for predicting electron configurations across the periodic table, relying on the relative energies of orbitals determined by quantum mechanical considerations. The specific order of orbital filling is governed by the Madelung rule, also known as the n + ℓ rule, which arranges subshells by increasing values of the sum of the principal quantum number n and the azimuthal quantum number ℓ; for subshells with equal n + ℓ, the one with lower n is filled first. This empirical ordering ensures that orbitals are populated as 1s, 2s, 2p, 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, 5s, 4d, 5p, 6s, 4f, 5d, 6p, and so on. For example, the 4s orbital (n=4, ℓ=0, n+ℓ=4) precedes the 3d orbital (n=3, ℓ=2, n+ℓ=5), reflecting the subtle energy interplay in multi-electron atoms due to screening and penetration effects. The rule was first articulated by Charles Janet in 1929 and independently formalized by Erwin Madelung in 1936, based on spectroscopic observations of atomic energy levels.[25] Complementing these filling guidelines are the Pauli exclusion principle and Hund's rules, which dictate how electrons are distributed within orbitals and subshells. The Pauli exclusion principle states that no two electrons in an atom can have the same set of four quantum numbers (n, ℓ, m_ℓ, m_s), limiting each orbital to a maximum of two electrons with opposite spins. This arises from the antisymmetric nature of the fermionic wave function for electrons, ensuring distinct quantum states for each particle. Formulated by Wolfgang Pauli in 1925, the principle explains the discrete structure of atomic spectra and the capacity of shells. Hund's rules further refine the arrangement within degenerate orbitals (those of equal energy, such as the three 2p orbitals). The first rule specifies that the ground state term has the maximum possible spin multiplicity (2S + 1, where S is the total spin quantum number), achieved by placing electrons in degenerate orbitals with parallel spins before pairing them, to maximize exchange energy and minimize electron-electron repulsion. The second rule states that, for states of maximum multiplicity, the one with maximum orbital angular momentum L has the lowest energy. These rules, developed by Friedrich Hund between 1925 and 1927, prioritize configurations that lower the overall energy through reduced Coulomb interactions. As a result of these principles, each orbital accommodates at most two electrons, leading to a maximum occupancy of 2(2ℓ + 1) electrons per subshell and 2n² electrons per shell. For instance, the s subshell (ℓ=0) holds 2 electrons, p (ℓ=1) holds 6, d (ℓ=2) holds 10, and f (ℓ=3) holds 14. This capacity aligns with the periodic table's block structure, where s and p fill to complete periods, and d and f define transition and inner transition series. The Madelung ordering is often visualized using the diagonal rule, a mnemonic diagram that lists subshells along diagonals in a table starting from the upper left: 1s, then downward to 2s and across to 2p, then 3s, 3p, 4s, 3d, 4p, and continuing similarly. This arrow-following pattern succinctly captures the filling sequence without memorizing the full n + ℓ progression, aiding in the construction of electron configurations for elements.[26]Historical Development

The concept of electron configuration originated with Niels Bohr's 1913 atomic model, which proposed that electrons orbit the nucleus in discrete, stationary circular paths characterized by a principal quantum number , allowing up to electrons per shell without distinguishing subshells.[27] This model successfully explained the hydrogen spectrum but lacked detail for multi-electron atoms, treating shells as simple capacity-limited rings.[28] In 1916, Arnold Sommerfeld extended Bohr's framework by introducing elliptical orbits, incorporating a second quantum number (the azimuthal quantum number) to account for the fine structure in atomic spectra observed through relativistic effects and precession.[29] This refinement allowed for subshell-like variations within shells, laying groundwork for more nuanced electron arrangements, though still within the old quantum theory paradigm. By 1925, Wolfgang Pauli formulated the exclusion principle based on spectroscopic anomalies, positing that no two electrons in an atom could share the same set of quantum numbers, which provided a fundamental limit on electron occupancy per state.[30] Building on these ideas, Edmund Stoner in 1924 and Charles Bury in 1921 independently proposed groupings of electrons into subshells with capacities of 2, 8, and 18 electrons, correlating these with quantum numbers and explaining periodic trends in atomic properties.[31][32] In the mid-1920s, Friedrich Hund developed rules for filling degenerate orbitals to maximize total spin multiplicity, ensuring the lowest energy ground state, while John Slater advanced the theoretical notation for configurations in his 1929 work on complex spectra.[33] The transition to full quantum mechanics culminated in Paul Dirac's 1928 relativistic equation, which incorporated special relativity and predicted spin-1/2 particles, enabling accurate descriptions of inner-shell electrons in heavy atoms where velocities approach light speed.[34] For heavy elements, this leads to significant relativistic corrections, including the Dirac-Coulomb effects that contract s- and p-orbitals while expanding d- and f-orbitals, altering expected configurations and influencing chemical properties like gold's color and mercury's liquidity.[35]Atomic Configurations

Periodic Table Arrangements

The periodic table is organized into blocks that correspond to the subshells being filled with electrons according to the Aufbau principle and Madelung rule, reflecting the sequential addition of electrons to atomic orbitals as atomic number increases.[36] This arrangement groups elements with similar valence electron configurations, influencing their chemical properties and trends across periods and groups. The s-block comprises Groups 1 and 2 (alkali and alkaline earth metals), where elements have 1 or 2 valence electrons in the ns subshell of the outermost shell.[37] These configurations, such as Li ([He] 2s¹) and Mg ([Ne] 3s²), contribute to high reactivity due to the low ionization energies of the single or paired s electrons, facilitating easy loss to form positive ions.[38] The p-block includes Groups 13 through 18, with elements featuring 1 to 6 valence electrons in the np subshell.[39] As electrons fill the p orbitals across a period, non-metallicity increases from left to right, exemplified by configurations like B ([He] 2s² 2p¹) transitioning to Ne ([He] 2s² 2p⁶), where the increasing nuclear charge pulls electrons closer, enhancing electronegativity and forming covalent bonds in later groups.[36] The d-block, or transition metals in Groups 3 through 12, involves filling of the (n-1)d subshell with 1 to 10 electrons, often alongside ns electrons.[37] This partial d-orbital occupancy leads to variable oxidation states and characteristic properties like colored compounds and catalytic activity, as seen in Sc ([Ar] 4s² 3d¹) to Zn ([Ar] 4s² 3d¹⁰).[38] The f-block consists of the lanthanides and actinides, where the (n-2)f subshell fills with 1 to 14 electrons.[39] The poor shielding by 4f electrons in lanthanides causes the lanthanide contraction, a gradual decrease in atomic radii across the series due to increasing effective nuclear charge, which affects subsequent element sizes in the periodic table.[40] A similar actinide contraction occurs for 5f elements.[41] This block structure sets the stage for the 18-electron rule in transition metal complexes, where d-block elements achieve stability analogous to noble gas configurations by accommodating up to 18 valence electrons in coordination spheres. To illustrate, the electron configurations of the first 24 elements follow the block filling pattern:| Atomic Number | Element | Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | H | 1s¹ |

| 2 | He | 1s² |

| 3 | Li | [He] 2s¹ |

| 4 | Be | [He] 2s² |

| 5 | B | [He] 2s² 2p¹ |

| 6 | C | [He] 2s² 2p² |

| 7 | N | [He] 2s² 2p³ |

| 8 | O | [He] 2s² 2p⁴ |

| 9 | F | [He] 2s² 2p⁵ |

| 10 | Ne | [He] 2s² 2p⁶ |

| 11 | Na | [Ne] 3s¹ |

| 12 | Mg | [Ne] 3s² |

| 13 | Al | [Ne] 3s² 3p¹ |

| 14 | Si | [Ne] 3s² 3p² |

| 15 | P | [Ne] 3s² 3p³ |

| 16 | S | [Ne] 3s² 3p⁴ |

| 17 | Cl | [Ne] 3s² 3p⁵ |

| 18 | Ar | [Ne] 3s² 3p⁶ |

| 19 | K | [Ar] 4s¹ |

| 20 | Ca | [Ar] 4s² |

| 21 | Sc | [Ar] 4s² 3d¹ |

| 22 | Ti | [Ar] 4s² 3d² |

| 23 | V | [Ar] 4s² 3d³ |

| 24 | Cr | [Ar] 4s¹ 3d⁵ |

Exceptions and Shortcomings

The Aufbau principle provides a simplified model for predicting electron configurations by filling orbitals in order of increasing energy, but it overlooks significant electron-electron repulsion, which can alter orbital energies and lead to deviations from the expected filling order.[42] This repulsion becomes particularly influential in transition metals, where d-orbitals compete closely in energy with s-orbitals, favoring configurations that minimize pairwise interactions. Additionally, the principle neglects relativistic effects, which are negligible for light elements but contract s-orbitals and expand d- and f-orbitals in heavy atoms, thereby shifting configuration preferences.[43] Prominent exceptions occur in the first-row transition metals, where stability from half-filled or fully filled d-subshells overrides the standard filling. For chromium (Z=24), the ground-state configuration is [Ar] 4s¹ 3d⁵ instead of the expected [Ar] 4s² 3d⁴, as the half-filled 3d subshell provides greater exchange energy and reduced repulsion.[42] Similarly, copper (Z=29) adopts [Ar] 4s¹ 3d¹⁰ rather than [Ar] 4s² 3d⁹, benefiting from the fully filled 3d¹⁰ subshell's enhanced stability.[44] Further deviations appear in later transition series, driven by analogous stability gains. Niobium (Z=41) has [Kr] 5s¹ 4d⁴, molybdenum (Z=42) [Kr] 5s¹ 4d⁵, ruthenium (Z=44) [Kr] 5s¹ 4d⁷, rhodium (Z=45) [Kr] 5s¹ 4d⁸, palladium (Z=46) [Kr] 4d¹⁰, silver (Z=47) [Kr] 5s¹ 4d¹⁰, gold (Z=79) [Xe] 6s¹ 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰, platinum (Z=78) [Xe] 6s¹ 4f¹⁴ 5d⁹, and these configurations prioritize d-subshell completion over s² filling due to lower overall energy from reduced electron interactions.[45] In heavy elements like gold, relativistic effects dominate these exceptions; the contraction of the 6s orbital increases its binding energy, making the [Xe] 4f¹⁴ 5d¹⁰ 6s¹ configuration more stable than a 6s² alternative, influencing properties such as gold's nobility and color.[46] This direct relativistic stabilization, combined with indirect expansion of 5d orbitals, exemplifies how high nuclear charge amplifies velocity-dependent corrections in the Dirac equation.[43] Beyond single-configuration approximations, many atomic ground states involve multi-configuration effects, where the wavefunction is a linear combination of several Slater determinants to account for electron correlation. For instance, in transition metals, near-degeneracy of 4s and 3d orbitals leads to configurations like 4s¹ 3d⁵ mixing with others, yielding a more accurate description than pure Aufbau predictions. Advanced post-Hartree-Fock methods, such as multiconfiguration Dirac-Fock or coupled-cluster approaches, reveal additional exceptions in superheavy elements by incorporating both correlation and relativity; for elements beyond Z=100, these calculations predict irregular fillings in 7s, 6d, and 5f subshells due to enhanced electron interactions and orbital instabilities not captured by simpler models.[47]Transition Metal Ionization

In transition metal atoms, the valence electron configuration typically features both ns and (n-1)d orbitals occupied, such as [Ar] 4s² 3d^x for first-row elements, but upon ionization to form cations, the ns electrons (e.g., 4s) are removed first, followed by electrons from the (n-1)d subshell.[48] This sequence occurs despite the higher principal quantum number of the ns orbital because the 4s electrons experience lower effective nuclear charge and thus have lower ionization energies compared to the more tightly bound 3d electrons in multi-electron atoms.[8] The resulting ions have electron configurations where the outer s subshell is empty, leading to d^n configurations that influence their chemical properties, such as variable oxidation states.[49] For example, neutral iron (Fe) has the configuration [Ar] 4s² 3d⁶, but the Fe²⁺ ion loses both 4s electrons to yield [Ar] 3d⁶, and further ionization to Fe³⁺ removes a 3d electron, resulting in [Ar] 3d⁵. This pattern exemplifies the common +2 and +3 oxidation states in first-row transition metals, with many elements exhibiting multiple stable states due to the similar energies of 4s and 3d electrons, allowing sequential removal without prohibitive energy costs.[48] The stability of these d^n configurations in ions is further modulated by crystal field theory, which describes how ligands in coordination complexes split the degenerate (n-1)d orbitals into sets of different energies, such as the lower-energy t_{2g} and higher-energy e_g orbitals in octahedral fields.[50] This splitting, quantified by the crystal field splitting energy Δ, influences electron pairing and overall ion stability, with high-spin or low-spin arrangements depending on whether Δ is larger or smaller than the electron pairing energy.[51] For instance, in aqueous solutions, the splitting favors certain oxidation states by stabilizing specific d-electron counts. The lanthanide contraction, arising from poor shielding by 4f electrons in the lanthanide series, causes a gradual decrease in atomic and ionic radii across the 4f block, resulting in second- and third-row transition metal ions (4d and 5d series) having sizes similar to their first-row (3d) counterparts despite higher nuclear charge.[49] This contraction enhances the densities and effective nuclear attraction in heavier transition metal ions, affecting their reactivity and preference for higher oxidation states compared to lighter analogs. Common ions from scandium to zinc in the first row illustrate these d^n configurations, typically achieving +2 or +3 charges by losing 4s electrons first:| Element | Common Ion | Electron Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Sc | Sc³⁺ | [Ar] |

| Ti | Ti³⁺ | [Ar] 3d¹ |

| V | V³⁺ | [Ar] 3d² |

| Cr | Cr³⁺ | [Ar] 3d³ |

| Mn | Mn²⁺ | [Ar] 3d⁵ |

| Fe | Fe²⁺ | [Ar] 3d⁶ |

| Co | Co²⁺ | [Ar] 3d⁷ |

| Ni | Ni²⁺ | [Ar] 3d⁸ |

| Cu | Cu²⁺ | [Ar] 3d⁹ |

| Zn | Zn²⁺ | [Ar] 3d¹⁰ |