Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

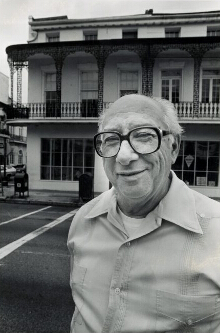

Cosimo Matassa

View on Wikipedia

Cosimo Vincent Matassa (April 13, 1926 – September 11, 2014) was an American recording engineer and studio owner, responsible for many R&B and early rock and roll recordings.

Key Information

Life and career

[edit]Matassa was born in New Orleans in 1926.[1][2] In 1944 he began studies as a chemistry major at Tulane University, which he abandoned after completing five semesters of course work.[3] In 1945, at the age of 18, Matassa opened the J&M Recording Studio at the back of his family's shop on Rampart Street, on the border of the French Quarter in New Orleans.[1] In 1955, he moved to the larger Cosimo Recording Studio on Gov. Nichols Street, nearby in the French Quarter.[1][4]

As an engineer and proprietor, Matassa was crucial to the development of the sound of R&B, rock and soul of the 1950s and 1960s, often working with the producers Dave Bartholomew and Allen Toussaint. He recorded many hits, including Fats Domino’s "The Fat Man" (a contender for the first rock and roll record), Little Richard's "Tutti Frutti", and records by Ray Charles, Lee Dorsey, Dr. John, Smiley Lewis, Bobby Mitchell, Tommy Ridgley, the Spiders and many others. He was responsible for developing what became known as the New Orleans sound, with strong drums, heavy guitar and bass, heavy piano, light horns and a strong vocal lead. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Matassa also managed the successful white New Orleans rock-and-roll performer Jimmy Clanton.[5]

Matassa is interviewed on screen in the 2005 documentary film Make It Funky!, which presents a history of New Orleans music and its influence on rhythm and blues, rock and roll, funk and jazz.[6][7]

Matassa retired from the music business in the 1980s to manage the family's food store, Matassa's Market, in the French Quarter.[8] He died on September 11, 2014, aged 88, in New Orleans.[9]

Awards and honors

[edit]In December 1999, J&M Recording Studio was designated as a historic landmark.[8]

In October 2007, Matassa was honored for his contributions to Louisiana music with induction into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame. In the same year he was also given a Grammy Trustees Award.[10]

On September 24, 2010, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum designated J&M Recording Studio a historic Rock and Roll Landmark, one of 11 nationwide.[11]

In 2012, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland as a nonperformer.[12] He was inducted to the Blues Hall of Fame in 2013.[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Unterberger, Richie (April 13, 1926). "Cosimo Matassa – Music Biography, Credits and Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ Komorowski, Adam. Liner notes. The Cosimo Matassa Story (CD).

- ^ Martin, Douglas (September 12, 2014). "Cosimo Matassa, Whose Studio Created a Rock 'n' Roll Sound, Dies at 88". New York Times.

- ^ "Cosimo Matassa". www.rockhall.com. Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved August 14, 2017.

- ^ Billboard, May 23, 1960. p. 30.

- ^ "IAJE What's Going On". Jazz Education Journal. 37 (5). Manhattan, Kansas: International Association of Jazz Educators: 87. April 2005. ISSN 1540-2886. ProQuest 1370090.

- ^ Make It Funky! (DVD). Culver City, California: Sony Pictures Home Entertainment. 2005. ISBN 9781404991583. OCLC 61207781. 11952.

- ^ a b ""New Orleans sound" Legend Cosimo Matassa Has Died". Bestofneworleans.com. Retrieved September 13, 2014.

- ^ Spera, Keith. "Cosimo Matassa, New Orleans Recording Studio Owner, Engineer and Rock 'n' Roll Pioneer, Has Died". Times-Picayune, September 11, 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2014.

- ^ "Cosimo Matassa Dies: Engineer and Recording Academy Trustees Award Recipient Dies at 88". Grammy.com. September 11, 2014. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ^ "Cosimo Matassa's J&M Recording Studio Named Rock and Roll Landmark". NOLA.com. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ "Guns n' Roses Inducted into Rock and Roll Hall of Fame". Bbc.co.uk. December 7, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ^ "2013 Blues Hall of Fame Inductees Announced". Blues.org. Archived from the original on October 26, 2010. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

External links

[edit]- Cosimo Matassa at IMDb

- Cosimo Matassa at AllMusic

- Cosimo Matassa discography at Discogs

- "Cosimo Matassa" by Matthew Sakakeeny, 2003, at Roll With It

- J&M Recording Studio, curated by Ponderosa Stomp Foundation

- Oral History Interview with Cosimo Matassa at The Historic New Orleans Collection