Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Counterion

View on Wikipedia

In chemistry, a counterion (sometimes written as "counter ion", pronounced as such) is the ion that accompanies an ionic species in order to maintain electric neutrality. In table salt (NaCl, also known as sodium chloride) the sodium ion (positively charged) is the counterion for the chloride ion (negatively charged) and vice versa.

A counterion will be more commonly referred to as an anion or a cation, depending on whether it is negatively or positively charged. Thus, the counterion to an anion will be a cation, and vice versa.

In biochemistry, counterions are generally vaguely defined. Depending on their charge, proteins are associated with a variety of smaller anions and cations. In plant cells, the anion malate is often accumulated in the vacuole to decrease water potential and drive cell expansion. To maintain neutrality, K+ ions are often accumulated as the counterion. Ion permeation through hydrophobic cell walls is mediated by ion transport channels. Nucleic acids are anionic, the corresponding cations are often protonated polyamines.

Interfacial chemistry

[edit]Counterions are the mobile ions in ion exchange polymers and colloids.[1] Ion-exchange resins are polymers with a net negative or positive charge. Cation-exchange resins consist of an anionic polymer with countercations, typically Na+ (sodium). The resin has a higher affinity for highly charged countercations, for example by Ca2+ (calcium) in the case of water softening. Correspondingly, anion-exchange resins are typically provided in the form of chloride Cl−, which is a highly mobile counteranion.

Counterions are used in phase-transfer catalysis. In a typical application lipophilic countercation such as benzalkonium solubilizes reagents in organic solvents.

Solution chemistry

[edit]Solubility of salts in organic solvents is a function of both the cation and the anion. The solubility of cations in organic solvents can be enhanced when the anion is lipophilic. Similarly, the solubility of anions in organic solvents is enhanced with lipophilic cations. The most common lipophilic cations are quaternary ammonium cations, called "quat salts".

- Lipophilic counteranions

-

Lithium tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)borate is the lithium salt of a highly lipophilic tetraarylborate anion, often referred to as a weakly coordinating anion.[2]

-

Tetraphenylborate is less lipophilic than the perfluorinated derivative, but widely used as a precipitating agent.

-

Hexafluorophosphate is a common weakly coordinating anion.

-

As illustrated by the small counteranion tetrafluoroborate (BF−

4), lipophilic cations tend to be symmetric and singly charged.

- Lipophilic countercations

-

Bis(triphenylphosphine)iminium chloride is the chloride salt of a bulky lipophilic phosphonium cation [Ph3PNPPh3]+.

-

Tetraphenylphosphonium chloride (C6H5)4PCl, abbreviated Ph4PCl or PPh4Cl is the chloride of a symmetrical phosphonium cation that is often used in organometallic chemistry. The arsonium salt is also well known.

-

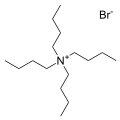

The bromide salt of tetrabutylammonium, one of the most common counter cations. Many analogous "quat salts" are known.

-

Alkali metal cations bound by crown ethers are common lipophilic countercations, as illustrated by [Li(12-crown-4)2]+.

Many cationic organometallic complexes are isolated with inert, noncoordinating counterions. Ferrocenium tetrafluoroborate is one such example.

Electrochemistry

[edit]In order to achieve high ionic conductivity, electrochemical measurements are conducted in the presence of excess electrolyte. In water the electrolyte is often a simple salt such as potassium chloride. For measurements in nonaqueous solutions, salts composed of both lipophilic cations and anions are employed, e.g., tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate. Even in such cases potentials are influenced by ion-pairing, an effect that is accentuated in solvents of low dielectric constant.[3]

Counterion stability

[edit]For many applications, the counterion simply provides charge and lipophilicity that allows manipulation of its partner ion. The counterion is expected to be chemically inert. For counteranions, inertness is expressed in terms of low Lewis basicity. The counterions are ideally rugged and unreactive. For quaternary ammonium and phosphonium countercations, inertness is related to their resistance of degradation by strong bases and strong nucleophiles.

References

[edit]- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "counter-ions". doi:10.1351/goldbook.C01371

- ^ I. Krossing and I. Raabe (2004). "Noncoordinating Anions - Fact or Fiction? A Survey of Likely Candidates". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 43 (16): 2066–2090. doi:10.1002/anie.200300620. PMID 15083452.

- ^ Geiger, W. E., Barrière, F., "Organometallic Electrochemistry Based on Electrolytes Containing Weakly-Coordinating Fluoroarylborate Anions", Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 1030. doi:10.1021/ar1000023

Counterion

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Basic Concepts

A counterion is an ion of opposite charge to a principal ionic species, serving to maintain electrical neutrality in ionic compounds, electrolyte solutions, or charged macromolecular systems such as polyelectrolytes.[1] For instance, in sodium chloride (NaCl), the sodium cation (Na⁺) acts as the counterion to the chloride anion (Cl⁻), balancing the overall charge of the compound.[10] This pairing ensures that the net charge in the system is zero, a requirement for stability in ionic assemblies.[11] The fundamental principle underlying counterions is charge balance, where the sum of positive and negative charges in an ionic system equals zero. In simple salts like MX (where M⁺ is the cation and X⁻ is the anion), this is expressed by equal concentrations of the oppositely charged ions: [M⁺] = [X⁻]. More generally, electroneutrality is maintained via ∑ z_i = 0, where z_i is the charge and is the concentration of each ion species. Counterions are distinct from co-ions, which carry the same charge as the principal ion and do not contribute to direct charge compensation; for example, in a cation-exchange resin with fixed anionic sites, SO₄²⁻ acts as a co-ion to the fixed anions but requires additional cations like Na⁺ as counterions for balance.[12] In polyelectrolytes, such as charged polymers like sodium polyacrylate, small counterions (e.g., Na⁺) neutralize the fixed charges along the polymer backbone, influencing the chain's conformation and solubility.[13] The concept of counterions traces its roots to the late 19th-century theory of electrolytic dissociation proposed by Svante Arrhenius in 1884, which described how electrolytes in solution separate into oppositely charged ions to achieve conductivity and neutrality, laying the groundwork for understanding ionic pairing.[14] The specific term "counterion" emerged in chemical literature around 1940, reflecting its application in contexts like coordination chemistry and ion exchange.[15] Formally, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines counter-ions in specialized domains, such as in colloid chemistry as low-molecular-mass ions of opposite charge to a colloidal ion (PAC, 1972, 31, 577).[16] To reliably identify counterions in ionic salts, orthogonal analytical methods are employed, including ion chromatography, which is particularly effective for anions such as halides, mass spectrometry for detailed structural confirmation, elemental analysis to verify salt composition and stoichiometry, and classical precipitation tests such as the silver nitrate (AgNO₃) test for halide ions.[17][18][19][20][21]Types and Common Examples

Counterions are broadly classified into anionic and cationic types based on their charge, serving to maintain electrical neutrality with oppositely charged species in ionic systems. Anionic counterions, which carry a negative charge, pair with cationic species; common examples include chloride (Cl⁻) and sulfate (SO₄²⁻) ions, often encountered in simple electrolyte salts like sodium chloride or magnesium sulfate. Conversely, cationic counterions, positively charged, accompany anionic species; representative cases are sodium (Na⁺) and tetraalkylammonium ions, such as tetrabutylammonium (Bu₄N⁺), used in various salt formations to enhance solubility or stability.[22] In inorganic contexts, a prominent example is sodium polystyrene sulfonate, where Na⁺ ions serve as counterions to the negatively charged sulfonate groups (-SO₃⁻) attached to a polystyrene polymer backbone, forming a structure conceptually depicted as a linear chain of phenyl rings bearing sulfonate pendants balanced by mobile sodium cations for charge neutrality. This compound is widely used in ion-exchange resins due to its ability to selectively bind cations. Organic counterions, such as tetraalkylammonium cations, are frequently paired with carboxylate anions (R-COO⁻) in ionic liquids, exemplified by tetrabutylammonium acetate, where the bulky organic cation improves the hydrophobicity and phase behavior of the salt for applications in green chemistry solvents.[23][24] In biochemical systems, counterions play crucial roles in maintaining ionic balance within cellular compartments. For instance, in plant vacuoles, particularly in guard cells, potassium ions (K⁺) are accompanied by malate (⁻OOC-CH₂-CH(OH)-COO⁻) as an organic anionic counterion, facilitating osmotic regulation and stomatal opening through vacuolar accumulation. A unique aspect in protein biochemistry is the role of chloride ions as counterions to positively charged lysine residues (Lys⁺, with -NH₃⁺ side chains), which helps screen electrostatic repulsions and stabilize protein folding, as observed in nucleosome complexes where Cl⁻ bridges lysine-arginine interactions with DNA phosphates. This classification aligns with the principle of charge neutrality, ensuring balanced electrostatics in diverse chemical environments.[25][26]Solution Chemistry

Behavior in Electrolyte Solutions

In electrolyte solutions, counterions dissociate from their partner ions in polar solvents like water, where the high dielectric constant screens electrostatic attractions and promotes separation, as described by Arrhenius' theory of electrolytic dissociation.[27] The extent of this dissociation increases with the solvent's dielectric constant, which diminishes the Coulombic forces between oppositely charged species, allowing ions to behave more independently in dilute conditions.[27] Once dissociated, counterions undergo solvation, forming hydration shells in aqueous media whose stability depends on the ion's charge density. Smaller ions like Li⁺, with higher charge density, exhibit stronger hydration and a more ordered first (and potentially second) shell compared to larger ions like Cs⁺, which form weaker, less structured shells due to lower charge density.[28] This variation influences water structure around the ions, as captured by the Hofmeister series, which ranks counterions by their ability to modulate solubility: kosmotropic ions (e.g., Li⁺ at the strongly hydrated end) enhance water ordering and promote salting-out effects, while chaotropic ions (e.g., Cs⁺ or SCN⁻) disrupt it, leading to salting-in.[29][30] Lipophilic counterions, such as quaternary ammonium cations, enhance the solubility of ionic compounds in organic solvents with low dielectric constants by forming ion pairs that reduce overall polarity and facilitate dissociation in nonpolar environments.[31] For instance, these counterions enable greater swelling and solubility of polyelectrolytes in solvents like hydrocarbons, where traditional hydrophilic ions would fail.[31] The interactions among counterions and partner ions in these solutions are quantified by the Debye-Hückel limiting law, which predicts the mean activity coefficient for dilute electrolytes: Here, is a temperature- and solvent-dependent constant (approximately 0.509 for water at 25°C), and are the ion charges, and is the ionic strength, directly influenced by counterion concentration as .[32] This law accounts for the ionic atmosphere of counterions surrounding a central ion, which screens its charge and affects effective concentrations. In dilute solutions of NaCl, for example, Na⁺ and Cl⁻ counterions dissociate completely and behave independently, producing two particles per formula unit and thereby doubling colligative properties like osmotic pressure or freezing point depression compared to nonelectrolytes of equivalent molarity; however, increasing concentration introduces ion interactions that deviate from ideal behavior.[33]Ion Pairing and Association

Ion pairing in electrolyte solutions involves the association of oppositely charged ions into distinct species, which can be classified as contact ion pairs (CIP), where ions are directly bonded without intervening solvent molecules, or solvent-separated ion pairs (SSIP), where one or more solvent molecules occupy the space between the ions.[34] This distinction arises from the balance between electrostatic attraction and solvation effects, with CIP forming in lower dielectric media where solvent screening is weaker, and SSIP prevailing in higher dielectric solvents. Bjerrum theory provides a foundational framework for understanding the critical distance at which pairing occurs, defining the Bjerrum length as the distance beyond which ions behave independently, calculated as , where ions within this distance are considered paired.[35] The extent of ion pairing is quantified by association constants, often derived from the Fuoss equation, which models the probability of ion encounter and pair formation:where is Avogadro's number, is the ion contact distance, is the potential energy, is Boltzmann's constant, and is temperature; this integral simplifies in low dielectric solvents by emphasizing short-range Coulombic interactions.[36][37] In non-aqueous solvents like acetonitrile, where the dielectric constant is around 36, ion pairing is more pronounced than in water, leading to reduced ionic conductivity as paired ions contribute less to charge transport compared to free ions; for example, tetraethylammonium chloride in acetonitrile exhibits measurable association, with conductivity dropping due to the formation of neutral pairs that do not migrate under an electric field.[38][39] A key distinction within ion pairs is between tight (contact) and loose (solvent-separated) configurations, where tight pairs involve direct ion-ion contact and exhibit minimal solvent intervention, while loose pairs allow partial solvation. This affects reaction kinetics in organic synthesis, as tight pairs can shield reactive sites, slowing nucleophilic attacks, whereas loose pairs facilitate ion exchange and enhance rates in solvolysis reactions.[40] In dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), a polar aprotic solvent with a dielectric constant of about 47, many salts such as lithium perchlorate form contact (tight) ion pairs, which alter spectroscopic properties like Raman shifts due to changes in vibrational modes from ion-solvent and ion-ion interactions.[41][42]

![Lithium tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)borate is the lithium salt of a highly lipophilic tetraarylborate anion, often referred to as a weakly coordinating anion.[2]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/90/Lithium-tetrakis%28pentafluorophenyl%29borate-2D-skeletal.png/250px-Lithium-tetrakis%28pentafluorophenyl%29borate-2D-skeletal.png)

![Bis(triphenylphosphine)iminium chloride is the chloride salt of a bulky lipophilic phosphonium cation [Ph3PNPPh3]+.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/PPNCl.png/250px-PPNCl.png)

![Alkali metal cations bound by crown ethers are common lipophilic countercations, as illustrated by [Li(12-crown-4)2]+.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/da/Bis%2812-crown-4%29lithium-cation-from-xtal-3D-balls-B.png/120px-Bis%2812-crown-4%29lithium-cation-from-xtal-3D-balls-B.png)