Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Chemistry

View on Wikipedia

| Part of a series on |

| Chemistry |

|---|

|

Chemistry is the scientific study of the properties and behavior of matter.[1][2] It is a physical science within the natural sciences that studies the chemical elements that make up matter and compounds made of atoms, molecules and ions: their composition, structure, properties, behavior and the changes they undergo during reactions with other substances.[3][4][5][6] Chemistry also addresses the nature of chemical bonds in chemical compounds.

In the scope of its subject, chemistry occupies an intermediate position between physics and biology.[7] It is sometimes called the central science because it provides a foundation for understanding both basic and applied scientific disciplines at a fundamental level.[8] For example, chemistry explains aspects of plant growth (botany), the formation of igneous rocks (geology), how atmospheric ozone is formed and how environmental pollutants are degraded (ecology), the properties of the soil on the Moon (cosmochemistry), how medications work (pharmacology), and how to collect DNA evidence at a crime scene (forensics).

Chemistry has existed under various names since ancient times.[9] It has evolved, and now chemistry encompasses various areas of specialisation, or subdisciplines, that continue to increase in number and interrelate to create further interdisciplinary fields of study. The applications of various fields of chemistry are used frequently for economic purposes in the chemical industry.

Etymology

[edit]The word chemistry comes from a modification during the Renaissance of the word alchemy, which referred to an earlier set of practices that encompassed elements of chemistry, metallurgy, philosophy, astrology, astronomy, mysticism, and medicine. Alchemy is often associated with the quest to turn lead or other base metals into gold, though alchemists were also interested in many of the questions of modern chemistry.[10][11]

The modern word alchemy in turn is derived from the Arabic word al-kīmīā (الكیمیاء). This may have Egyptian origins since al-kīmīā is derived from the Ancient Greek χημία, which is in turn derived from the word Kemet, which is the ancient name of Egypt in the Egyptian language.[12] Alternately, al-kīmīā may derive from χημεία 'cast together'.[13]

Modern principles

[edit]

The current model of atomic structure is the quantum mechanical model.[14] Traditional chemistry starts with the study of elementary particles, atoms, molecules,[15] substances, metals, crystals and other aggregates of matter. Matter can be studied in solid, liquid, gas and plasma states, in isolation or in combination. The interactions, reactions and transformations that are studied in chemistry are usually the result of interactions between atoms, leading to rearrangements of the chemical bonds which hold atoms together. Such behaviors are studied in a chemistry laboratory.

The chemistry laboratory stereotypically uses various forms of laboratory glassware. However glassware is not central to chemistry, and a great deal of experimental (as well as applied/industrial) chemistry is done without it.

A chemical reaction is a transformation of some substances into one or more different substances.[16] The basis of such a chemical transformation is the rearrangement of electrons in the chemical bonds between atoms. It can be symbolically depicted through a chemical equation, which usually involves atoms as subjects. The number of atoms on the left and the right in the equation for a chemical transformation is equal. (When the number of atoms on either side is unequal, the transformation is referred to as a nuclear reaction or radioactive decay.) The type of chemical reactions a substance may undergo and the energy changes that may accompany it are constrained by certain basic rules, known as chemical laws.

Energy and entropy considerations are invariably important in almost all chemical studies. Chemical substances are classified in terms of their structure, phase, as well as their chemical compositions. They can be analyzed using the tools of chemical analysis, e.g. spectroscopy and chromatography. Scientists engaged in chemical research are known as chemists.[17] Most chemists specialize in one or more sub-disciplines. Several concepts are essential for the study of chemistry; some of them are:[18]

Matter

[edit]In chemistry, matter is defined as anything that has rest mass and volume (it takes up space) and is made up of particles. The particles that make up matter have rest mass as well – not all particles have rest mass, such as the photon. Matter can be a pure chemical substance or a mixture of substances.[19]

Atom

[edit]

The atom is the basic unit of chemistry. It consists of a dense core called the atomic nucleus surrounded by a space occupied by an electron cloud. The nucleus is made up of positively charged protons and uncharged neutrons (together called nucleons), while the electron cloud consists of negatively charged electrons which orbit the nucleus. In a neutral atom, the negatively charged electrons balance out the positive charge of the protons. The nucleus is dense; the mass of a nucleon is approximately 1,836 times that of an electron, yet the radius of an atom is about 10,000 times that of its nucleus.[20][21]

The atom is also the smallest entity that can be envisaged to retain the chemical properties of the element, such as electronegativity, ionization potential, preferred oxidation state(s), coordination number, and preferred types of bonds to form (e.g., metallic, ionic, covalent).

Element

[edit]

A chemical element is a pure substance which is composed of a single type of atom, characterized by its particular number of protons in the nuclei of its atoms, known as the atomic number and represented by the symbol Z. The mass number is the sum of the number of protons and neutrons in a nucleus. Although all the nuclei of all atoms belonging to one element will have the same atomic number, they may not necessarily have the same mass number; atoms of an element which have different mass numbers are known as isotopes. For example, all atoms with 6 protons in their nuclei are atoms of the chemical element carbon, but atoms of carbon may have mass numbers of 12 or 13.[21]

The standard presentation of the chemical elements is in the periodic table, which orders elements by atomic number. The periodic table is arranged in groups, or columns, and periods, or rows. The periodic table is useful in identifying periodic trends.[22]

Compound

[edit]

A compound is a pure chemical substance composed of more than one element. The properties of a compound bear little similarity to those of its elements.[23] The standard nomenclature of compounds is set by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC). Organic compounds are named according to the organic nomenclature system.[24] The names for inorganic compounds are created according to the inorganic nomenclature system. When a compound has more than one component, then they are divided into two classes, the electropositive and the electronegative components.[25] In addition the Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) has devised a method to index chemical substances. In this scheme each chemical substance is identifiable by a number known as its CAS registry number.

Molecule

[edit]

A molecule is the smallest indivisible portion of a pure chemical substance that has its unique set of chemical properties, that is, its potential to undergo a certain set of chemical reactions with other substances. However, this definition only works well for substances that are composed of molecules, which is not true of many substances (see below). Molecules are typically a set of atoms bound together by covalent bonds, such that the structure is electrically neutral and all valence electrons are paired with other electrons either in bonds or in lone pairs.

Thus, molecules exist as electrically neutral units, unlike ions. When this rule is broken, giving the "molecule" a charge, the result is sometimes named a molecular ion or a polyatomic ion. However, the discrete and separate nature of the molecular concept usually requires that molecular ions be present only in well-separated form, such as a directed beam in a vacuum in a mass spectrometer. Charged polyatomic collections residing in solids (for example, common sulfate or nitrate ions) are generally not considered "molecules" in chemistry. Some molecules contain one or more unpaired electrons, creating radicals. Most radicals are comparatively reactive, but some, such as nitric oxide (NO) can be stable.

The "inert" or noble gas elements (helium, neon, argon, krypton, xenon and radon) are composed of lone atoms as their smallest discrete unit, but the other isolated chemical elements consist of either molecules or networks of atoms bonded to each other in some way. Identifiable molecules compose familiar substances such as water, air, and many organic compounds like alcohol, sugar, gasoline, and the various pharmaceuticals.

However, not all substances or chemical compounds consist of discrete molecules, and indeed most of the solid substances that make up the solid crust, mantle, and core of the Earth are chemical compounds without molecules. These other types of substances, such as ionic compounds and network solids, are organized in such a way as to lack the existence of identifiable molecules per se. Instead, these substances are discussed in terms of formula units or unit cells as the smallest repeating structure within the substance. Examples of such substances are mineral salts (such as table salt), solids like carbon and diamond, metals, and familiar silica and silicate minerals such as quartz and granite.

One of the main characteristics of a molecule is its geometry often called its structure. While the structure of diatomic, triatomic or tetra-atomic molecules may be trivial, (linear, angular pyramidal etc.) the structure of polyatomic molecules, that are constituted of more than six atoms (of several elements) can be crucial for its chemical nature.

Substance and mixture

[edit]  | |

| |

| |

| Examples of pure chemical substances. From left to right: the elements tin (Sn) and sulfur (S), diamond (an allotrope of carbon), sucrose (pure sugar), and sodium chloride (salt) and sodium bicarbonate (baking soda), which are both ionic compounds. |

A chemical substance is a kind of matter with a definite composition and set of properties.[26] A collection of substances is called a mixture. Examples of mixtures are air and alloys.[27]

Mole and amount of substance

[edit]The mole is a unit of measurement that denotes an amount of substance (also called chemical amount). One mole is defined to contain exactly 6.02214076×1023 particles (atoms, molecules, ions, or electrons), where the number of particles per mole is known as the Avogadro constant.[28] Molar concentration is the amount of a particular substance per volume of solution, and is commonly reported in mol/dm3.[29]

Phase

[edit]

In addition to the specific chemical properties that distinguish different chemical classifications, chemicals can exist in several phases. For the most part, the chemical classifications are independent of these bulk phase classifications; however, some more exotic phases are incompatible with certain chemical properties. A phase is a set of states of a chemical system that have similar bulk structural properties, over a range of conditions, such as pressure or temperature.

Physical properties, such as density and refractive index tend to fall within values characteristic of the phase. The phase of matter is defined by the phase transition, which is when energy put into or taken out of the system goes into rearranging the structure of the system, instead of changing the bulk conditions.

Sometimes the distinction between phases can be continuous instead of having a discrete boundary; in this case the matter is considered to be in a supercritical state. When three states meet based on the conditions, it is known as a triple point and since this is invariant, it is a convenient way to define a set of conditions.

The most familiar examples of phases are solids, liquids, and gases. Many substances exhibit multiple solid phases. For example, there are three phases of solid iron (alpha, gamma, and delta) that vary based on temperature and pressure. A principal difference between solid phases is the crystal structure, or arrangement, of the atoms. Another phase commonly encountered in the study of chemistry is the aqueous phase, which is the state of substances dissolved in aqueous solution (that is, in water).

Less familiar phases include plasmas, Bose–Einstein condensates and fermionic condensates and the paramagnetic and ferromagnetic phases of magnetic materials. While most familiar phases deal with three-dimensional systems, it is also possible to define analogs in two-dimensional systems, which has received attention for its relevance to systems in biology.

Bonding

[edit]

Atoms sticking together in molecules or crystals are said to be bonded with one another. A chemical bond may be visualized as the multipole balance between the positive charges in the nuclei and the negative charges oscillating about them.[30] More than simple attraction and repulsion, the energies and distributions characterize the availability of an electron to bond to another atom.

The chemical bond can be a covalent bond, an ionic bond, a hydrogen bond or just because of Van der Waals force. Each of these kinds of bonds is ascribed to some potential. These potentials create the interactions which hold atoms together in molecules or crystals. In many simple compounds, valence bond theory, the Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion model (VSEPR), and the concept of oxidation number can be used to explain molecular structure and composition.

An ionic bond is formed when a metal loses one or more of its electrons, becoming a positively charged cation, and the electrons are then gained by the non-metal atom, becoming a negatively charged anion. The two oppositely charged ions attract one another, and the ionic bond is the electrostatic force of attraction between them. For example, sodium (Na), a metal, loses one electron to become an Na+ cation while chlorine (Cl), a non-metal, gains this electron to become Cl−. The ions are held together due to electrostatic attraction, and that compound sodium chloride (NaCl), or common table salt, is formed.

In a covalent bond, one or more pairs of valence electrons are shared by two atoms: the resulting electrically neutral group of bonded atoms is termed a molecule. Atoms will share valence electrons in such a way as to create a noble gas electron configuration (eight electrons in their outermost shell) for each atom. Atoms that tend to combine in such a way that they each have eight electrons in their valence shell are said to follow the octet rule. However, some elements like hydrogen and lithium need only two electrons in their outermost shell to attain this stable configuration; these atoms are said to follow the duet rule, and in this way they are reaching the electron configuration of the noble gas helium, which has two electrons in its outer shell.

Similarly, theories from classical physics can be used to predict many ionic structures. With more complicated compounds, such as metal complexes, valence bond theory is less applicable and alternative approaches, such as the molecular orbital theory, are generally used.

Energy

[edit]In the context of chemistry, energy is an attribute of a substance as a consequence of its atomic, molecular or aggregate structure. Since a chemical transformation is accompanied by a change in one or more of these kinds of structures, it is invariably accompanied by an increase or decrease of energy of the substances involved. Some energy is transferred between the surroundings and the reactants of the reaction in the form of heat or light; thus the products of a reaction may have more or less energy than the reactants.

A reaction is said to be exergonic if the final state is lower on the energy scale than the initial state; in the case of endergonic reactions the situation is the reverse. A reaction is said to be exothermic if the reaction releases heat to the surroundings; in the case of endothermic reactions, the reaction absorbs heat from the surroundings.

Chemical reactions are invariably not possible unless the reactants surmount an energy barrier known as the activation energy. The speed of a chemical reaction (at given temperature T) is related to the activation energy E, by the Boltzmann's population factor – that is the probability of a molecule to have energy greater than or equal to E at the given temperature T. This exponential dependence of a reaction rate on temperature is known as the Arrhenius equation. The activation energy necessary for a chemical reaction to occur can be in the form of heat, light, electricity or mechanical force in the form of ultrasound.[31]

A related concept free energy, which also incorporates entropy considerations, is a very useful means for predicting the feasibility of a reaction and determining the state of equilibrium of a chemical reaction, in chemical thermodynamics. A reaction is feasible only if the total change in the Gibbs free energy is negative, ; if it is equal to zero the chemical reaction is said to be at equilibrium.

There exist only limited possible states of energy for electrons, atoms and molecules. These are determined by the rules of quantum mechanics, which require quantization of energy of a bound system. The atoms/molecules in a higher energy state are said to be excited. The molecules/atoms of substance in an excited energy state are often much more reactive; that is, more amenable to chemical reactions.

The phase of a substance is invariably determined by its energy and the energy of its surroundings. When the intermolecular forces of a substance are such that the energy of the surroundings is not sufficient to overcome them, it occurs in a more ordered phase like liquid or solid as is the case with water (H2O); a liquid at room temperature because its molecules are bound by hydrogen bonds.[32] Whereas hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a gas at room temperature and standard pressure, as its molecules are bound by weaker dipole–dipole interactions.

The transfer of energy from one chemical substance to another depends on the size of energy quanta emitted from one substance. However, heat energy is often transferred more easily from almost any substance to another because the phonons responsible for vibrational and rotational energy levels in a substance have much less energy than photons invoked for the electronic energy transfer. Thus, because vibrational and rotational energy levels are more closely spaced than electronic energy levels, heat is more easily transferred between substances relative to light or other forms of electronic energy. For example, ultraviolet electromagnetic radiation is not transferred with as much efficacy from one substance to another as thermal or electrical energy.

The existence of characteristic energy levels for different chemical substances is useful for their identification by the analysis of spectral lines. Different kinds of spectra are often used in chemical spectroscopy, e.g. IR, microwave, NMR, ESR, etc. Spectroscopy is also used to identify the composition of remote objects – like stars and distant galaxies – by analyzing their radiation spectra.

The term chemical energy is often used to indicate the potential of a chemical substance to undergo a transformation through a chemical reaction or to transform other chemical substances.

Reaction

[edit]

When a chemical substance is transformed as a result of its interaction with another substance or with energy, a chemical reaction is said to have occurred. A chemical reaction is therefore a concept related to the "reaction" of a substance when it comes in close contact with another, whether as a mixture or a solution; exposure to some form of energy, or both. It results in some energy exchange between the constituents of the reaction as well as with the system environment, which may be designed vessels—often laboratory glassware.

Chemical reactions can result in the formation or dissociation of molecules, that is, molecules breaking apart to form two or more molecules or rearrangement of atoms within or across molecules. Chemical reactions usually involve the making or breaking of chemical bonds. Oxidation, reduction, dissociation, acid–base neutralization and molecular rearrangement are some examples of common chemical reactions.

A chemical reaction can be symbolically depicted through a chemical equation. While in a non-nuclear chemical reaction the number and kind of atoms on both sides of the equation are equal, for a nuclear reaction this holds true only for the nuclear particles viz. protons and neutrons.[33]

The sequence of steps in which the reorganization of chemical bonds may be taking place in the course of a chemical reaction is called its mechanism. A chemical reaction can be envisioned to take place in a number of steps, each of which may have a different speed. Many reaction intermediates with variable stability can thus be envisaged during the course of a reaction. Reaction mechanisms are proposed to explain the kinetics and the relative product mix of a reaction. Many physical chemists specialize in exploring and proposing the mechanisms of various chemical reactions. Several empirical rules, like the Woodward–Hoffmann rules often come in handy while proposing a mechanism for a chemical reaction.

According to the IUPAC gold book, a chemical reaction is "a process that results in the interconversion of chemical species."[34] Accordingly, a chemical reaction may be an elementary reaction or a stepwise reaction. An additional caveat is made, in that this definition includes cases where the interconversion of conformers is experimentally observable. Such detectable chemical reactions normally involve sets of molecular entities as indicated by this definition, but it is often conceptually convenient to use the term also for changes involving single molecular entities (i.e. 'microscopic chemical events').

Ions and salts

[edit]

An ion is a charged species, an atom or a molecule, that has lost or gained one or more electrons. When an atom loses an electron and thus has more protons than electrons, the atom is a positively charged ion or cation. When an atom gains an electron and thus has more electrons than protons, the atom is a negatively charged ion or anion. Cations and anions can form a crystalline lattice of neutral salts, such as the Na+ and Cl− ions forming sodium chloride, or NaCl. Examples of polyatomic ions that do not split up during acid–base reactions are hydroxide (OH−) and phosphate (PO43−).

Plasma is composed of gaseous matter that has been completely ionized, usually through high temperature.

Acidity and basicity

[edit]

A substance can often be classified as an acid or a base. There are several different theories which explain acid–base behavior. The simplest is Arrhenius theory, which states that an acid is a substance that produces hydronium ions when it is dissolved in water, and a base is one that produces hydroxide ions when dissolved in water. According to Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, acids are substances that donate a positive hydrogen ion to another substance in a chemical reaction; by extension, a base is the substance which receives that hydrogen ion.

A third common theory is Lewis acid–base theory, which is based on the formation of new chemical bonds. Lewis theory explains that an acid is a substance which is capable of accepting a pair of electrons from another substance during the process of bond formation, while a base is a substance which can provide a pair of electrons to form a new bond. There are several other ways in which a substance may be classified as an acid or a base, as is evident in the history of this concept.[35]

Acid strength is commonly measured by two methods. One measurement, based on the Arrhenius definition of acidity, is pH, which is a measurement of the hydronium ion concentration in a solution, as expressed on a negative logarithmic scale. Thus, solutions that have a low pH have a high hydronium ion concentration and can be said to be more acidic. The other measurement, based on the Brønsted–Lowry definition, is the acid dissociation constant (Ka), which measures the relative ability of a substance to act as an acid under the Brønsted–Lowry definition of an acid. That is, substances with a higher Ka are more likely to donate hydrogen ions in chemical reactions than those with lower Ka values.

Redox

[edit]Redox (reduction-oxidation) reactions include all chemical reactions in which atoms have their oxidation state changed by either gaining electrons (reduction) or losing electrons (oxidation). Substances that have the ability to oxidize other substances are said to be oxidative and are known as oxidizing agents, oxidants or oxidizers. An oxidant removes electrons from another substance. Similarly, substances that have the ability to reduce other substances are said to be reductive and are known as reducing agents, reductants, or reducers.

A reductant transfers electrons to another substance and is thus oxidized itself. And because it "donates" electrons it is also called an electron donor. Oxidation and reduction properly refer to a change in oxidation number—the actual transfer of electrons may never occur. Thus, oxidation is better defined as an increase in oxidation number, and reduction as a decrease in oxidation number.

Equilibrium

[edit]Although the concept of equilibrium is widely used across sciences, in the context of chemistry, it arises whenever a number of different states of the chemical composition are possible, as for example, in a mixture of several chemical compounds that can react with one another, or when a substance can be present in more than one kind of phase.

A system of chemical substances at equilibrium, even though having an unchanging composition, is most often not static; molecules of the substances continue to react with one another thus giving rise to a dynamic equilibrium. Thus the concept describes the state in which the parameters such as chemical composition remain unchanged over time.

Chemical laws

[edit]Chemical reactions are governed by certain laws, which have become fundamental concepts in chemistry. Some of them are:

- Avogadro's law

- Beer–Lambert law

- Boyle's law (1662, relating pressure and volume)

- Charles's law (1787, relating volume and temperature)

- Fick's laws of diffusion

- Gay-Lussac's law (1809, relating pressure and temperature)

- Le Chatelier's principle

- Henry's law

- Hess's law

- Law of conservation of energy leads to the important concepts of equilibrium, thermodynamics, and kinetics.

- Law of conservation of mass continues to be conserved in isolated systems, even in modern physics. However, special relativity shows that due to mass–energy equivalence, whenever non-material "energy" (heat, light, kinetic energy) is removed from a non-isolated system, some mass will be lost with it. High energy losses result in loss of weighable amounts of mass, an important topic in nuclear chemistry.

- Law of definite composition, although in many systems (notably biomacromolecules and minerals) the ratios tend to require large numbers, and are frequently represented as a fraction.

- Law of multiple proportions

- Raoult's law

History

[edit]The history of chemistry spans a period from the ancient past to the present. Since several millennia BC, civilizations were using technologies that would eventually form the basis of the various branches of chemistry. Examples include extracting metals from ores, making pottery and glazes, fermenting beer and wine, extracting chemicals from plants for medicine and perfume, rendering fat into soap, making glass, and making alloys like bronze.

Chemistry was preceded by its protoscience, alchemy, which operated a non-scientific approach to understanding the constituents of matter and their interactions. Despite being unsuccessful in explaining the nature of matter and its transformations, alchemists set the stage for modern chemistry by performing experiments and recording the results. Robert Boyle, although skeptical of elements and convinced of alchemy, played a key part in elevating the "sacred art" as an independent, fundamental and philosophical discipline in his work The Sceptical Chymist (1661).[36]

While both alchemy and chemistry are concerned with matter and its transformations, the crucial difference was given by the scientific method that chemists employed in their work. Chemistry, as a body of knowledge distinct from alchemy, became an established science with the work of Antoine Lavoisier, who developed a law of conservation of mass that demanded careful measurement and quantitative observations of chemical phenomena. The history of chemistry afterwards is intertwined with the history of thermodynamics, especially through the work of Willard Gibbs.[37]

Definition

[edit]The definition of chemistry has changed over time, as new discoveries and theories add to the functionality of the science. The term "chymistry", in the view of noted scientist Robert Boyle in 1661, meant the subject of the material principles of mixed bodies.[38] In 1663, the chemist Christopher Glaser described "chymistry" as a scientific art, by which one learns to dissolve bodies, and draw from them the different substances on their composition, and how to unite them again, and exalt them to a higher perfection.[39]

The 1730 definition of the word "chemistry", as used by Georg Ernst Stahl, meant the art of resolving mixed, compound, or aggregate bodies into their principles; and of composing such bodies from those principles.[40] In 1837, Jean-Baptiste Dumas considered the word "chemistry" to refer to the science concerned with the laws and effects of molecular forces.[41] This definition further evolved until, in 1947, it came to mean the science of substances: their structure, their properties, and the reactions that change them into other substances—a characterization accepted by Linus Pauling.[42] More recently, in 1998, Professor Raymond Chang broadened the definition of "chemistry" to mean the study of matter and the changes it undergoes.[43]

Background

[edit]

Early civilizations, such as the Egyptians,[44] Babylonians, and Indians,[45] amassed practical knowledge concerning the arts of metallurgy, pottery and dyes, but did not develop a systematic theory.

A basic chemical hypothesis first emerged in Classical Greece with the theory of four elements as propounded definitively by Aristotle stating that fire, air, earth and water were the fundamental elements from which everything is formed as a combination. Greek atomism dates back to 440 BC, arising in works by philosophers such as Democritus and Epicurus. In 50 BCE, the Roman philosopher Lucretius expanded upon the theory in his poem De rerum natura (On The Nature of Things).[46][47] Unlike modern concepts of science, Greek atomism was purely philosophical in nature, with little concern for empirical observations and no concern for chemical experiments.[48]

An early form of the idea of conservation of mass is the notion that "Nothing comes from nothing" in Ancient Greek philosophy, which can be found in Empedocles (approx. 4th century BC): "For it is impossible for anything to come to be from what is not, and it cannot be brought about or heard of that what is should be utterly destroyed."[49] and Epicurus (3rd century BC), who, describing the nature of the Universe, wrote that "the totality of things was always such as it is now, and always will be".[50]

In the Hellenistic world the art of alchemy first proliferated, mingling magic and occultism into the study of natural substances with the ultimate goal of transmuting elements into gold and discovering the elixir of eternal life.[51] Work, particularly the development of distillation, continued in the early Byzantine period with the most famous practitioner being the 4th century Greek-Egyptian Zosimos of Panopolis.[52] Alchemy continued to be developed and practised throughout the Arab world after the Muslim conquests,[53] and from there, and from the Byzantine remnants,[54] diffused into medieval and Renaissance Europe through Latin translations.

The Arabic works attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan introduced a systematic classification of chemical substances, and provided instructions for deriving an inorganic compound (sal ammoniac or ammonium chloride) from organic substances (such as plants, blood, and hair) by chemical means.[55] Some Arabic Jabirian works (e.g., the "Book of Mercy", and the "Book of Seventy") were later translated into Latin under the Latinized name "Geber",[56] and in 13th-century Europe an anonymous writer, usually referred to as pseudo-Geber, started to produce alchemical and metallurgical writings under this name.[57] Later influential Muslim philosophers, such as Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī[58] and Avicenna[59] disputed the theories of alchemy, particularly the theory of the transmutation of metals.

Improvements of the refining of ores and their extractions to smelt metals was widely used source of information for early chemists in the 16th century, among them Georg Agricola (1494–1555), who published his major work De re metallica in 1556. His work, describing highly developed and complex processes of mining metal ores and metal extraction, were the pinnacle of metallurgy during that time. His approach removed all mysticism associated with the subject, creating the practical base upon which others could and would build. The work describes the many kinds of furnaces used to smelt ore, and stimulated interest in minerals and their composition. Agricola has been described as the "father of metallurgy" and the founder of geology as a scientific discipline.[63][61][62]

Under the influence of the Scientific Revolution and its new empirical methods propounded by Sir Francis Bacon and others, a group of chemists at Oxford, Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke and John Mayow began to reshape the old alchemical traditions into a scientific discipline. Boyle in particular questioned some commonly held chemical theories and argued for chemical practitioners to be more "philosophical" and less commercially focused in The Sceptical Chemyst.[36] He formulated Boyle's law, rejected the classical "four elements" and proposed a mechanistic alternative of atoms and chemical reactions that could be subject to rigorous experiment.[64]

In the following decades, many important discoveries were made, such as the nature of 'air' which was discovered to be composed of many different gases. The Scottish chemist Joseph Black and the Flemish Jan Baptist van Helmont discovered carbon dioxide, or what Black called 'fixed air' in 1754; Henry Cavendish discovered hydrogen and elucidated its properties and Joseph Priestley and, independently, Carl Wilhelm Scheele isolated pure oxygen. The theory of phlogiston (a substance at the root of all combustion) was propounded by the German Georg Ernst Stahl in the early 18th century and was only overturned by the end of the century by the French chemist Antoine Lavoisier, the chemical analogue of Newton in physics. Lavoisier did more than any other to establish the new science on proper theoretical footing, by elucidating the principle of conservation of mass and developing a new system of chemical nomenclature used to this day.[66]

English scientist John Dalton proposed the modern theory of atoms; that all substances are composed of indivisible 'atoms' of matter and that different atoms have varying atomic weights.

The development of the electrochemical theory of chemical combinations occurred in the early 19th century as the result of the work of two scientists in particular, Jöns Jacob Berzelius and Humphry Davy, made possible by the prior invention of the voltaic pile by Alessandro Volta. Davy discovered nine new elements including the alkali metals by extracting them from their oxides with electric current.[67]

British William Prout first proposed ordering all the elements by their atomic weight as all atoms had a weight that was an exact multiple of the atomic weight of hydrogen. J.A.R. Newlands devised an early table of elements, which was then developed into the modern periodic table of elements[70] in the 1860s by Dmitri Mendeleev and independently by several other scientists including Julius Lothar Meyer.[71][72] The inert gases, later called the noble gases were discovered by William Ramsay in collaboration with Lord Rayleigh at the end of the century, thereby filling in the basic structure of the table.

Organic chemistry was developed by Justus von Liebig and others, following Friedrich Wöhler's synthesis of urea.[73] Other crucial 19th century advances were; an understanding of valence bonding (Edward Frankland in 1852) and the application of thermodynamics to chemistry (J. W. Gibbs and Svante Arrhenius in the 1870s).

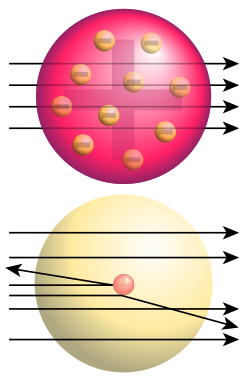

Bottom: Observed results: a small portion of the particles were deflected, indicating a small, concentrated charge.

At the turn of the twentieth century the theoretical underpinnings of chemistry were finally understood due to a series of remarkable discoveries that succeeded in probing and discovering the very nature of the internal structure of atoms. In 1897, J.J. Thomson of the University of Cambridge discovered the electron and soon after the French scientist Becquerel as well as the couple Pierre and Marie Curie investigated the phenomenon of radioactivity. In a series of pioneering scattering experiments Ernest Rutherford at the University of Manchester discovered the internal structure of the atom and the existence of the proton, classified and explained the different types of radioactivity and successfully transmuted the first element by bombarding nitrogen with alpha particles.

His work on atomic structure was improved on by his students, the Danish physicist Niels Bohr, the Englishman Henry Moseley and the German Otto Hahn, who went on to father the emerging nuclear chemistry and discovered nuclear fission. The electronic theory of chemical bonds and molecular orbitals was developed by the American scientists Linus Pauling and Gilbert N. Lewis.

The year 2011 was declared by the United Nations as the International Year of Chemistry.[74] It was an initiative of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, and of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization and involves chemical societies, academics, and institutions worldwide and relied on individual initiatives to organize local and regional activities.

Practice

[edit]In the practice of chemistry, pure chemistry is the study of the fundamental principles of chemistry, while applied chemistry applies that knowledge to develop technology and solve real-world problems.

Subdisciplines

[edit]Chemistry is typically divided into several major sub-disciplines. There are also several main cross-disciplinary and more specialized fields of chemistry.[75]

- Analytical chemistry is the analysis of material samples to gain an understanding of their chemical composition and structure. Analytical chemistry incorporates standardized experimental methods in chemistry. These methods may be used in all subdisciplines of chemistry, excluding purely theoretical chemistry.[76]

- Biochemistry is the study of the chemicals, chemical reactions and interactions that take place at a molecular level in living organisms. Biochemistry is highly interdisciplinary, covering medicinal chemistry, neurochemistry, molecular biology, forensics, plant science and genetics.[78]

- Inorganic chemistry is the study of the properties and reactions of inorganic compounds, such as metals and minerals.[79] The distinction between organic and inorganic disciplines is not absolute and there is much overlap, most importantly in the sub-discipline of organometallic chemistry.

- Materials chemistry is the preparation, characterization, and understanding of solid state components or devices with a useful current or future function.[82] The field is a new breadth of study in graduate programs, and it integrates elements from all classical areas of chemistry like organic chemistry, inorganic chemistry, and crystallography with a focus on fundamental issues that are unique to materials. Primary systems of study include the chemistry of condensed phases (solids, liquids, polymers) and interfaces between different phases.

- Neurochemistry is the study of neurochemicals; including transmitters, peptides, proteins, lipids, sugars, and nucleic acids; their interactions, and the roles they play in forming, maintaining, and modifying the nervous system.

- Nuclear chemistry is the study of how subatomic particles come together and make nuclei. Modern transmutation is a large component of nuclear chemistry, and the table of nuclides is an important result and tool for this field. In addition to medical applications, nuclear chemistry encompasses nuclear engineering which explores the topic of using nuclear power sources for generating energy.[83][84]

- Organic chemistry is the study of the structure, properties, composition, mechanisms, and reactions of organic compounds. An organic compound is defined as any compound based on a carbon skeleton. Organic compounds can be classified, organized and understood in reactions by their functional groups, unit atoms or molecules that show characteristic chemical properties in a compound.[86]

- Physical chemistry is the study of the physical and fundamental basis of chemical systems and processes. In particular, the energetics and dynamics of such systems and processes are of interest to physical chemists. Important areas of study include chemical thermodynamics, chemical kinetics, electrochemistry, statistical mechanics, spectroscopy, and more recently, astrochemistry. Physical chemistry has large overlap with molecular physics. Physical chemistry involves the use of infinitesimal calculus in deriving equations. It is usually associated with quantum chemistry and theoretical chemistry. Physical chemistry is a distinct discipline from chemical physics, but again, there is very strong overlap.

- Theoretical chemistry is the study of chemistry via fundamental theoretical reasoning (usually within mathematics or physics). In particular the application of quantum mechanics to chemistry is called quantum chemistry. Since the end of the Second World War, the development of computers has allowed a systematic development of computational chemistry, which is the art of developing and applying computer programs for solving chemical problems. Theoretical chemistry has large overlap with (theoretical and experimental) condensed matter physics and molecular physics.

Other subdivisions include electrochemistry, femtochemistry, flavor chemistry, flow chemistry, immunohistochemistry, hydrogenation chemistry, mathematical chemistry, molecular mechanics, natural product chemistry, organometallic chemistry, petrochemistry, photochemistry, physical organic chemistry, polymer chemistry, radiochemistry, sonochemistry, supramolecular chemistry, synthetic chemistry, and many others.

Interdisciplinary

[edit]Interdisciplinary fields include agrochemistry, astrochemistry (and cosmochemistry), atmospheric chemistry, chemical engineering, chemical biology, chemo-informatics, environmental chemistry, geochemistry, green chemistry, immunochemistry, marine chemistry, materials science, mechanochemistry, medicinal chemistry, molecular biology, nanotechnology, oenology, pharmacology, phytochemistry, solid-state chemistry, surface science, thermochemistry, and many others.

Industry

[edit]The chemical industry represents an important economic activity worldwide. The global top 50 chemical producers in 2013 had sales of US$980.5 billion with a profit margin of 10.3%.[87]

Professional societies

[edit]- American Chemical Society

- American Society for Neurochemistry

- Chemical Institute of Canada

- Chemical Society of Peru

- International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry

- Royal Australian Chemical Institute

- Royal Netherlands Chemical Society

- Royal Society of Chemistry

- Society of Chemical Industry

- World Association of Theoretical and Computational Chemists

See also

[edit]- Comparison of software for molecular mechanics modeling

- Glossary of chemistry terms

- International Year of Chemistry

- List of chemists

- List of compounds

- List of important publications in chemistry

- List of unsolved problems in chemistry

- Outline of chemistry

- Periodic systems of small molecules

- Philosophy of chemistry

- Science tourism

References

[edit]- ^ Brown, Theodore L.; LeMay, H. Eugene Jr.; Bursten, Bruce E.; Murphey, Catherine J.; Woodward, Patrick M.; Stoltzfus, Matthew W.; Lufaso, Michael W. (2018). "Introduction: Matter, energy, and measurement". Chemistry: The Central Science (14th ed.). New York: Pearson. pp. 46–85. ISBN 978-0134414232.

- ^ Kofoed, Melissa; Miller, Shawn (2020). Introductory Chemistry. Utah State University: UEN Pressbooks.

- ^ "What is Chemistry?". Chemweb.ucc.ie. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "Definition of CHEMISTRY". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Definition of chemistry | Dictionary.com". www.dictionary.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- ^ "Chemistry Is Everywhere". American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 29 November 2020. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ^ Carsten Reinhardt. Chemical Sciences in the 20th Century: Bridging Boundaries. Wiley-VCH, 2001. ISBN 3-527-30271-9. pp. 1–2.

- ^ Theodore L. Brown, H. Eugene Lemay, Bruce Edward Bursten, H. Lemay. Chemistry: The Central Science. Prentice Hall; 8 ed. (1999). ISBN 0-13-010310-1. pp. 3–4.

- ^ "Chemistry – Chemistry and society". Britannica. Archived from the original on 6 May 2023. Retrieved 6 May 2023.

- ^ Ihde, Aaron J. (1984). The development of modern chemistry. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-64235-2.

- ^ Newman, William R. (2011). "What Have We Learned from the Recent Historiography of Alchemy?". Isis. 102 (2): 313–321. doi:10.1086/660140. ISSN 0021-1753. PMID 21874691.

- ^ "alchemy", entry in The Oxford English Dictionary, J.A. Simpson and E.S.C. Weiner, vol. 1, 2nd ed., 1989, ISBN 0-19-861213-3.

- ^ Weekley, Ernest (1967). Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-21873-2.

- ^ "chemical bonding". Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- ^ Anthony Carpi. Matter: Atoms from Democritus to Dalton, Archived 28 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ IUPAC, Gold Book Definition, Archived 4 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "California Occupational Guide Number 22: Chemists". Calmis.ca.gov. 29 October 1999. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ "General Chemistry Online – Companion Notes: Matter". Antoine.frostburg.edu. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Armstrong, James (2012). General, Organic, and Biochemistry: An Applied Approach. Brooks/Cole. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-534-49349-3.

- ^ Burrows et al. 2009, p. 13.

- ^ a b Housecroft & Sharpe 2008, p. 2.

- ^ Burrows et al. 2009, p. 110.

- ^ Burrows et al. 2009, p. 12.

- ^ "IUPAC Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry". Acdlabs.com. Archived from the original on 8 June 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Connelly, Neil G.; Damhus, Ture; Hartshom, Richard M.; Hutton, Alan T. (2005). Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry IUPAC Recommendations 2005. Cambridge: Royal Society of Chemistry Publishing / IUPAC. ISBN 0854044388. Retrieved 13 June 2022.

- ^ Hill, J. W.; Petrucci, R. H.; McCreary, T. W.; Perry, S. S. (2005). General Chemistry (4th ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 37.

- ^ Avedesian, M. M.; Baker, Hugh. Magnesium and Magnesium Alloys. ASM International. p. 59.

- ^ Burrows et al. 2009, p. 16.

- ^ Atkins & de Paula 2009, p. 9.

- ^ "Chemical Bonding by Anthony Carpi, PhD". visionlearning. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Reilly, Michael. (2007). Mechanical force induces chemical reaction, Archived 14 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine, NewScientist.com news service.

- ^ Changing States of Matter, Archived 28 April 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Chemforkids.com.

- ^ Chemical Reaction Equation, Archived 12 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, IUPAC Goldbook.

- ^ Gold Book Chemical Reaction, Archived 4 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, IUPAC Goldbook.

- ^ "History of Acidity". BBC. 27 May 2004. Archived from the original on 27 February 2009. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ a b Principe, L. (2011). "In retrospect: The Sceptical Chymist". Nature. 469 (7328): 30–31. Bibcode:2011Natur.469...30P. doi:10.1038/469030a. ISSN 1476-4687. S2CID 6490305.

- ^ "Selected Classic Papers from the History of Chemistry". Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2017.

- ^ Boyle, Robert (1661). The Sceptical Chymist. New York: Dover Publications, Incorporated (reprint). ISBN 978-0-486-42825-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Glaser, Christopher (1663). Traite de la chymie. Paris. as found in: Kim, Mi Gyung (2003). Affinity, That Elusive Dream – A Genealogy of the Chemical Revolution. The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-11273-4.

- ^ Stahl, George (1730). Philosophical Principles of Universal Chemistry. London, England.

- ^ Dumas, J. B. (1837). 'Affinite' (lecture notes), vii, p. 4. "Statique chimique", Paris, France: Académie des Sciences.

- ^ Pauling, Linus (1947). General Chemistry. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-486-65622-9.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Chang, Raymond (1998). Chemistry, 6th Ed. New York: McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-115221-1.

- ^ First chemists, Archived 8 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine, February 13, 1999, New Scientist.

- ^ Barnes, Ruth (2004). Textiles in Indian Ocean Societies. Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0415297660.

- ^ Lucretius. "de Rerum Natura (On the Nature of Things)". The Internet Classics Archive. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ^ Simpson, David (29 June 2005). "Lucretius (c. 99–55 BCE)". The Internet History of Philosophy. Archived from the original on 28 May 2010. Retrieved 10 November 2020.

- ^ Strodach, George K. (2012). The Art of Happiness. New York: Penguin Classics. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-14-310721-7.

- ^ Fr. 12; see pp. 291–292 of Kirk, G. S.; Raven, J. E.; Schofield, Malcolm (1983). The Presocratic Philosophers (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27455-5.

- ^ Long, A. A.; Sedley, D. N. (1987). "Epicureanism: The principals of conservation". The Hellenistic Philosophers. Vol 1: Translations of the principal sources with philosophical commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0-521-27556-9.

- ^ "International Year of Chemistry – The History of Chemistry". G.I.T. Laboratory Journal Europe. 25 February 2011. Archived from the original on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Bunch, Bryan H. & Hellemans, Alexander (2004). The History of Science and Technology. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-618-22123-3.

- ^ Morris Kline (1985) Mathematics for the nonmathematician. Archived 5 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Courier Dover Publications. p. 284. ISBN 0-486-24823-2.

- ^ Marcelin Berthelot, Collection des anciens alchimistes grecs (3 vol., Paris, France, 1887–1888, p. 161); F. Sherwood Taylor, "The Origins of Greek Alchemy", Ambix 1 (1937), p. 40.

- ^ Stapleton, Henry Enest; Azo, R. F.; Hidayat Husain, M. (1927). "Chemistry in Iraq and Persia in the Tenth Century A.D." Memoirs of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. VIII (6): 317–418. OCLC 706947607. pp. 338–340; Kraus, Paul (1942–1943). Jâbir ibn Hayyân: Contribution à l'histoire des idées scientifiques dans l'Islam. I. Le corpus des écrits jâbiriens. II. Jâbir et la science grecque. Cairo: Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. ISBN 978-3-487-09115-0. OCLC 468740510.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) vol. II, pp. 41–42. - ^ Darmstaedter, Ernst. "Liber Misericordiae Geber: Eine lateinische Übersetzung des gröβeren Kitâb l-raḥma", Archiv für Geschichte der Medizin, 17/4, 1925, pp. 181–197; Berthelot, Marcellin. "Archéologie et Histoire des sciences", Mémoires de l'Académie des sciences de l'Institut de France, 49, 1906, pp. 308–363; see also Forster, Regula. "Jābir b. Ḥayyān", Archived 18 April 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopaedia of Islam, Three.

- ^ Newman, William R. "New Light on the Identity of Geber", Sudhoffs Archiv, 1985, 69, pp. 76–90; Newman, William R. The Summa perfectionis of Pseudo-Geber: A critical ed., translation and study, Leiden: Brill, 1991, pp. 57–103. It has been argued by Ahmad Y. Al-Hassan that the pseudo-Geber works were actually translated into Latin from the Arabic (see Al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. "The Arabic Origin of the Summa and Geber Latin Works: A Refutation of Berthelot, Ruska, and Newman Based on Arabic Sources", in: Ahmad Y. Al-Hassan. Studies in al-Kimya': Critical Issues in Latin and Arabic Alchemy and Chemistry. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag, 2009, pp. 53–104; also available online. Archived 25 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Marmura, Michael E.; Nasr, Seyyed Hossein (1965). "An Introduction to Islamic Cosmological Doctrines. Conceptions of Nature and Methods Used for Its Study by the Ikhwan Al-Safa'an, Al-Biruni, and Ibn Sina by Seyyed Hossein Nasr". Speculum. 40 (4): 744–746. doi:10.2307/2851429. JSTOR 2851429.

- ^ Robert Briffault (1938). The Making of Humanity, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Marshall, James L.; Marshall, Virginia R. (Autumn 2005). "Rediscovery of the Elements: Agricola" (PDF). The Hexagon. 96 (3). Alpha Chi Sigma: 59. ISSN 0164-6109. OCLC 4478114. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Georgius Agricola". University of California – Museum of Paleontology. Retrieved 4 April 2019.

- ^ a b Rafferty, John P. (2012). Geological Sciences; Geology: Landforms, Minerals, and Rocks. New York: Britannica Educational Publishing, p. 10. ISBN 9781615305445

- ^ Karl Alfred von Zittel (1901). History of Geology and Palaeontology, p. 15.

- ^ "History – Robert Boyle (1627–1691)". BBC. Archived from the original on 9 January 2011. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- ^ Eagle, Cassandra T.; Sloan, Jennifer (1998). "Marie Anne Paulze Lavoisier: The Mother of Modern Chemistry". The Chemical Educator. 3 (5): 1–18. doi:10.1007/s00897980249a. S2CID 97557390.

- ^ Kim, Mi Gyung (2003). Affinity, that Elusive Dream: A Genealogy of the Chemical Revolution. MIT Press. p. 440. ISBN 978-0-262-11273-4.

- ^ Davy, Humphry (1808). "On some new Phenomena of Chemical Changes produced by Electricity, particularly the Decomposition of the fixed Alkalies, and the Exhibition of the new Substances, which constitute their Bases". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society. 98: 1–45. doi:10.1098/rstl.1808.0001. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ^ "A Brief History of the Development of Periodic Table". Chemistry 412 course notes. Western Oregon University. Archived from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- ^ Note. Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine. "...it is surely true that had Mendeleev never lived modern chemists would be using a Periodic Table" and "Dmitri Mendeleev". Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 2 July 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ Winter, Mark. "WebElements: the periodic table on the web". The University of Sheffield. Archived from the original on 4 January 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- ^ "Julius Lothar Meyer and Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev". Science History Institute. June 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "What makes these family likenesses among the elements? In the 1860s everyone was scratching their heads about that, and several scientists moved towards rather similar answers. The man who solved the problem most triumphantly was a young Russian called Dmitri Ivanovich Mendeleev, who visited the salt mine at Wieliczka in 1859." Bronowski, Jacob (1973). The Ascent of Man. Little, Brown and Company. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-316-10930-7.

- ^ Ihde, Aaron John (1984). The Development of Modern Chemistry. Courier Dover Publications. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-486-64235-2.

- ^ "Chemistry". Chemistry2011.org. Archived from the original on 8 October 2011. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ^ "Chemistry Subdisciplines". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ "Analytical Chemistry". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Skoog, Douglas A.; Holler, F. James; Crouch, Stanley R. (2018). Principles of instrumental analysis (7th ed.). Australia: Cengage Learning. p. 120. ISBN 978-1-305-57721-3.

- ^ "Studying Biochemistry". www.biochemistry.org. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Inorganic Chemistry". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 1 April 2024.

- ^ Kaminsky, Walter (1 January 1998). "Highly active metallocene catalysts for olefin polymerization". Journal of the Chemical Society, Dalton Transactions (9): 1413–1418. doi:10.1039/A800056E. ISSN 1364-5447.

- ^ "Polypropylene". pslc.ws. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Fahlman, Bradley D. (2011). Materials Chemistry (1st ed.). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands Springer e-books Imprint: Springer. pp. 1–4. ISBN 978-94-007-0693-4.

- ^ "Nuclear Chemistry". American Chemical Society. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "21: Nuclear Chemistry". Libretexts. 18 November 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ "Little Boy and Fat Man – Nuclear Museum". ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/. Retrieved 11 April 2024.

- ^ Brown, William Henry; Iverson, Brent L.; Anslyn, Eric V.; Foote, Christopher S. (2018). Organic chemistry (8th ed.). Boston, Massachusetts: Cengage Learning. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-305-58035-0.

- ^ Tullo, Alexander H. (28 July 2014). "C&EN's Global Top 50 Chemical Firms For 2014". Chemical & Engineering News. American Chemical Society. Archived from the original on 26 August 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

Bibliography

[edit]- Atkins, Peter; de Paula, Julio (2009) [1992]. Elements of Physical Chemistry (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922672-6.

- Burrows, Andrew; Holman, John; Parsons, Andrew; Pilling, Gwen; Price, Gareth (2009). Chemistry3. Italy: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927789-6.

- Housecroft, Catherine E.; Sharpe, Alan G. (2008) [2001]. Inorganic Chemistry (3rd ed.). Harlow, Essex: Pearson Education. ISBN 978-0-13-175553-6.

Further reading

[edit]Popular reading

- Atkins, P. W. Galileo's Finger (Oxford University Press) ISBN 0-19-860941-8

- Atkins, P. W. Atkins' Molecules (Cambridge University Press) ISBN 0-521-82397-8

- Kean, Sam. The Disappearing Spoon – and Other True Tales from the Periodic Table (Black Swan) London, England, 2010 ISBN 978-0-552-77750-6

- Levi, Primo The Periodic Table (Penguin Books) [1975] translated from the Italian by Raymond Rosenthal (1984) ISBN 978-0-14-139944-7

- Stwertka, A. A Guide to the Elements (Oxford University Press) ISBN 0-19-515027-9

- "Dictionary of the History of Ideas". Archived from the original on 10 March 2008.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 33–76.

Introductory undergraduate textbooks

- Atkins, P.W., Overton, T., Rourke, J., Weller, M. and Armstrong, F. Shriver and Atkins Inorganic Chemistry (4th ed.) 2006 (Oxford University Press) ISBN 0-19-926463-5

- Chang, Raymond. Chemistry 6th ed. Boston, Massachusetts: James M. Smith, 1998. ISBN 0-07-115221-0

- Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart; Wothers, Peter (2001). Organic Chemistry (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850346-0.

- Voet and Voet. Biochemistry (Wiley) ISBN 0-471-58651-X

Advanced undergraduate-level or graduate textbooks

- Atkins, P. W. Physical Chemistry (Oxford University Press) ISBN 0-19-879285-9

- Atkins, P. W. et al. Molecular Quantum Mechanics (Oxford University Press)

- McWeeny, R. Coulson's Valence (Oxford Science Publications) ISBN 0-19-855144-4

- Pauling, L. The Nature of the chemical bond (Cornell University Press) ISBN 0-8014-0333-2

- Pauling, L., and Wilson, E. B. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics with Applications to Chemistry (Dover Publications) ISBN 0-486-64871-0

- Smart and Moore. Solid State Chemistry: An Introduction (Chapman and Hall) ISBN 0-412-40040-5

- Stephenson, G. Mathematical Methods for Science Students (Longman) ISBN 0-582-44416-0

External links

[edit]Chemistry

View on GrokipediaCore Concepts

Matter and Its Properties

Matter is defined as anything that has mass and occupies space, possessing both volume and the ability to exert gravitational attraction. This fundamental concept forms the foundation of chemistry, encompassing all tangible substances from everyday objects to natural phenomena. Matter can exist in various forms and is characterized by observable attributes that distinguish one type from another. Matter is classified into two broad categories: pure substances and mixtures. Pure substances consist of a single type of particle and cannot be separated into simpler components by physical means; they are further divided into elements, which are basic substances like oxygen or gold that cannot be broken down chemically, and compounds, such as water or carbon dioxide, formed by combining elements in fixed ratios. Mixtures, on the other hand, comprise two or more substances that retain their individual properties and can be separated physically; these are subdivided into homogeneous mixtures, which have uniform composition throughout (e.g., saltwater solutions), and heterogeneous mixtures, which exhibit non-uniform regions (e.g., sand in water). Physical properties of matter are characteristics that can be observed or measured without altering the substance's chemical composition. Key examples include density, defined as mass per unit volume and measured by dividing the mass (often via a balance) by the volume (displaced or geometric calculation); color, assessed visually or spectrophotometrically; melting point, the temperature at which a solid becomes a liquid, determined using a melting point apparatus; and boiling point, the temperature at which a liquid turns to gas under standard pressure, measured with a thermometer in a controlled heating setup. These properties aid in identifying and characterizing matter, providing insights into its behavior under different conditions. Matter exists in four primary states: solid, liquid, gas, and plasma, each defined by the arrangement and movement of its particles. In solids, particles are tightly packed in a fixed, vibrating lattice, giving definite shape and volume; liquids feature particles close together but able to slide past one another, resulting in a definite volume but indefinite shape that conforms to the container; gases have particles far apart and moving rapidly in random directions, leading to neither fixed shape nor volume, expanding to fill available space; and plasma, an ionized gas, consists of charged particles (free electrons and ions) that conduct electricity, commonly observed in stars and lightning. Transitions between states occur with energy changes: melting converts solids to liquids by overcoming particle attractions; boiling (or vaporization) shifts liquids to gases by further increasing kinetic energy; and sublimation directly transforms solids to gases, as seen in dry ice. Properties of matter are categorized as extensive or intensive based on their dependence on sample size. Extensive properties, such as mass (measured by weighing) and volume (calculated via displacement or dimensions), vary with the amount of matter present. In contrast, intensive properties like temperature (gauged with thermometers) and pressure (measured by barometers or manometers) remain constant regardless of sample quantity, making them useful for material identification. During physical changes, such as state transitions or dissolving, the total mass of matter is conserved, meaning no matter is created or destroyed—the mass before equals the mass after the process. This principle, rooted in classical observations, underscores that physical processes merely rearrange matter without altering its total quantity.Atoms and Elements

Atoms are the fundamental building blocks of matter, as proposed by John Dalton in his atomic theory published in 1808. Dalton's theory, based on the laws of conservation of mass and definite proportions, posited five key postulates: all matter is composed of tiny, indivisible particles called atoms; atoms of the same element are identical in mass and properties, while atoms of different elements differ in mass and properties; atoms cannot be created or destroyed in chemical reactions but can rearrange; compounds form when atoms of different elements combine in simple whole-number ratios; and the relative numbers and kinds of atoms in a compound are constant across samples.[12] Although later discoveries revealed atoms are divisible and isotopes exist, Dalton's framework laid the foundation for modern chemistry by shifting from continuous to discrete views of matter.[12] Subatomic particles constitute the structure of atoms. The electron, with a charge of -1 and mass approximately 1/1836 atomic mass units (u), was discovered by J.J. Thomson in 1897 via cathode ray tube experiments, revealing negatively charged particles within atoms. The proton, positively charged at +1 and mass about 1 u, was identified by Ernest Rutherford in 1919 through alpha particle scattering, confirming a dense positive nucleus. The neutron, neutral with mass roughly 1 u, was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932 using beryllium bombardment, explaining isotopic mass variations. Protons and neutrons reside in the atomic nucleus, while electrons occupy the surrounding electron cloud or orbitals. The atomic number (Z) equals the number of protons in the nucleus, defining the element's identity, as established by Henry Moseley in 1913 through X-ray spectroscopy. The mass number (A) is the sum of protons and neutrons. Isotopes are atoms of the same element (same Z) but different A, such as carbon-12 and carbon-14, first recognized by Frederick Soddy in 1913. The atomic mass, reported in the periodic table, is the weighted average of naturally occurring isotopes' masses, accounting for their relative abundances. The periodic table organizes the 118 known elements based on increasing atomic number, refining Dmitri Mendeleev's 1869 arrangement by atomic mass that predicted undiscovered elements like gallium and germanium.[13] It features seven periods (horizontal rows) corresponding to principal electron shell fillings and 18 groups (vertical columns) sharing similar valence electron configurations and properties.[13] Key trends include atomic radius, which decreases across a period due to increasing effective nuclear charge and increases down a group from added electron shells; first ionization energy, the energy to remove an electron, which increases across periods (stronger nuclear pull) and decreases down groups (electrons farther from nucleus); and electronegativity, the ability to attract electrons in bonds, which rises across periods and falls down groups, quantified on the Pauling scale from 0.7 (francium) to 4.0 (fluorine).[13] A seminal discovery was hydrogen, the lightest element (Z=1), isolated and described as "inflammable air" by Henry Cavendish in 1766 through reactions of metals with acids in his London laboratory.[14] Cavendish noted its low density and combustion to form water, though Antoine Lavoisier later named it in 1783.[14] Elemental abundances vary by context, reflecting cosmic nucleosynthesis and geological processes. In the universe, hydrogen dominates at about 73.5% by mass, followed by helium at 23.8%, with oxygen (1%) and carbon (0.46%) next from stellar fusion; heavier elements total ~2%.[15] In Earth's crust, oxygen is most abundant at 46.6%, comprising silicates and oxides, followed by silicon (27.7%), aluminum (8.1%), and iron (5.0%).[16]| Top Elements in Earth's Crust (by mass %) |

|---|

| Oxygen: 46.6 |

| Silicon: 27.7 |

| Aluminum: 8.1 |

| Iron: 5.0 |

| Calcium: 3.6 |

| Top Elements in Human Body (by mass %) |

|---|

| Oxygen: 65 |

| Carbon: 18 |

| Hydrogen: 10 |

| Nitrogen: 3 |

| Calcium: 1.5 |