Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Rebound (basketball)

View on Wikipedia

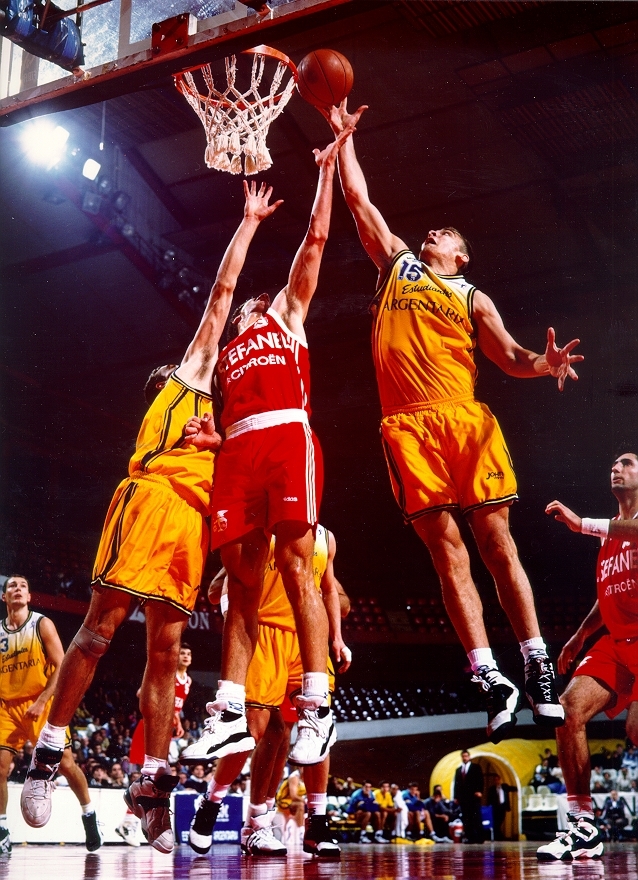

In basketball, a rebound, sometimes colloquially referred to as a board,[1] is a statistic awarded to a player who retrieves the ball after a missed field goal or free throw.[2]

Rebounds in basketball are a routine part in the game; if a shot is successfully made possession of the ball will change, otherwise the rebound allows the defensive team to take possession. Rebounds are also given to a player who tips in a missed shot on their team's offensive end. A rebound can be grabbed by either an offensive player or a defensive player.

Rebounds are divided into two main categories: "offensive rebounds", in which the ball is recovered by the offensive side and does not change possession, and "defensive rebounds", in which the defending team gains possession. Most rebounds are defensive because the team on defense tends to be in better position (i.e., closer to the basket) to recover missed shots. Offensive rebounds give the offensive team another opportunity to score whether right away or by resetting the offense. A block is not considered a rebound.

A ball does not need to actually "rebound" off the rim or backboard for a rebound to be credited. Rebounds are credited after any missed shot, including air balls which completely miss the basket and board. If a player takes a shot and misses and the ball bounces on the ground before someone picks it up, then the person who picks up the ball is credited for a rebound. Rebounds are credited to the first player that gains clear possession of the ball or to the player that successfully deflects the ball into the basket for a score. A rebound is credited to a team when it gains possession of the ball after any missed shot that is not cleared by a single player (e.g., deflected out of bounds after the shot, blocked out of bounds, bounced directly off the rim out of bounds). A team rebound is never credited to any player, and is generally considered to be a formality as according to the rules of basketball, every missed shot must be rebounded whether a single player controls the ball or not.

Great rebounders tend to be tall and strong. Because height is so important, most rebounds are made by centers and power forwards, who are often positioned closer to the basket. The lack of height can sometimes be compensated by the strength to box out taller players away from the ball to capture the rebound. For example, Charles Barkley once led the league in rebounding despite usually being much shorter than his counterparts.

Some shorter guards can be excellent rebounders as well such as point guard Jason Kidd who led the New Jersey Nets in rebounding for several years. But height can also be an advantage for rebounding. Great rebounders must also have a keen sense of timing and positioning. Great leaping ability is an important asset, but not necessary. Players such as Larry Bird and Moses Malone were excellent rebounders, but were never known for their leaping ability. Bird has stated, "Most rebounds are taken below the rim. That's where I get mine".[3]

Boxing out

[edit]

Players position themselves in the best spot to get the rebound by "boxing out"—i.e., by positioning themselves between an opponent and the basket, and maintaining body contact with the player he is guarding. The action can also be called "blocking out". A team can be boxed out by several players using this technique to stop the other team from rebounding. Because fighting for a rebound can be very physical, rebounding is often regarded as "grunt work" or a "hustle" play. Overly aggressive boxing out or preventing being boxed out can lead to personal fouls.

Statistics

[edit]Statistics of a player's "rebounds per game" or "rebounding average" measure a player's rebounding effectiveness by dividing the number of rebounds by the number of games played. Rebound rates go beyond raw rebound totals by taking into account external factors, such as the number of shots taken in games and the percentage of those shots that are made (the total number of rebounds available).

Rebounds were first officially recorded in the NBA during the 1950–51 season. Both offensive and defensive rebounds were first officially recorded in the NBA during the 1973–74 season and ABA during the 1967–68 season.

New camera technology has been able to shed much more light on where missed shots will likely land.[4]

Notable rebounders in the NBA

[edit]

- Wilt Chamberlain – led the NBA in rebounds in 11 different seasons, has the most career rebounds in the regular season (23,924), the highest career average (22.9 rpg), the single season rebounding records in total (2,149) and average (27.2 rpg), most rebounds in a regular season game (55) and playoff game (41) in the NBA, and has the most career All-Star Game rebounds (197).[2]

- Bill Russell – led the league in rebounding 4 times. He was the first player to average over 20 rebounds per game in the regular season, ranks second to Chamberlain in regular season total (21,620) and average (22.5) rebounds, averaged more than 20 rebounds per game in 10 of 13 seasons played, grabbed 51 rebounds in a single game (second best ever), grabbed a record 32 rebounds in one half, grabbed 40 rebounds in the NBA Finals twice, and is the all-time playoff leader in total (4,104) and average (24.9 rpg) rebounds.

- Bob Pettit – averaged 20.3 rebounds per game in the 1960–61 season, his career average of 16.2 rebounds per game is third all-time, and holds the top two performances for rebounds in an NBA All-Star Game with 26 (in 1958) and 27 (in 1962).

- Nate Thurmond – averaged more than 20 rebounds per game in two seasons (including 22.0 rpg in the 1967–68 season), career average of 15.0 rpg, and holds the regular season NBA record for rebounds in a single quarter with 18. He is also the only player besides Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain and Jerry Lucas to record more than 40 rebounds in a single game.

- Jerry Lucas – averaged more than 20 rebounds per game in two seasons (including 21.1 rpg in the 1965–66 season), and had a career average of 15.6 rpg. Along with Russell, Chamberlain and Thurmond is one of only four players to grab at least 40 rebounds in a single game.

- Moses Malone – led the NBA in rebounds per game in six different seasons including a high of 17.6 rpg in the 1978–79 season, ranks first in career offensive rebounds in the regular season (offensive and defensive rebounds were not recorded separately until the 1973–74 season), and ranks fifth all-time in total regular season rebounds in the NBA (third if ABA rebounds are also included).

- Dennis Rodman – led the league in rebounds per game an NBA record 7 consecutive seasons, including a high of 18.7 rpg in the 1991–92 season. Rodman holds the top seven rebound rate seasons since the 1970–71 season. Rodman has the highest career rebounding average of any player since the NBA began recording offensive and defensive rebounds in 1973–74. The shortest on the list at 6'7".

- Dwight Howard – only player to lead the NBA in rebounding three times before turning 25 years old. Howard has led the league in rebounding five times.

- Andre Drummond — has led the NBA in rebounds per game in four different seasons. Drummond has the highest career rebounds per game average of any player to play in the 21st century.

See also

[edit]- List of NBA regular season records

- List of NBA career rebounding leaders

- List of NBA annual rebounding leaders

- List of NBA single-game rebounding leaders

- List of National Basketball Association top individual rebounding season averages

- Rebound (sports)

- The Gun (basketball)

- List of Philippine Basketball Association career rebounding leaders

References

[edit]- ^ Frazier, Walt; Sachare, Alex (1998). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Basketball. Penguin. p. 346. ISBN 9780028626796. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- ^ a b "Rebound Definition - Sporting Charts". www.sportingcharts.com. Archived from the original on July 15, 2012. Retrieved June 15, 2015.

- ^ CNN/SI - 33: Larry Bird enters the Hall of Fame Archived February 10, 2001, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Goldsberry, Kirk (October 14, 2014). "How Rebounds Work". Grantland. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014.

External links

[edit]- List of NBA rebound leaders Archived March 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine