Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

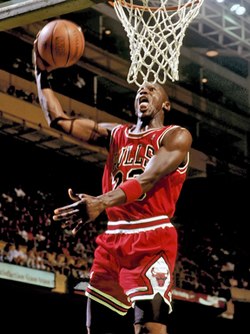

Slam dunk

View on Wikipedia

A slam dunk, also simply known as a dunk, is a type of basketball shot that is performed when a player jumps in the air, controls the ball above the horizontal plane of the rim, and shoves the ball directly through the basket with either one or both hands.[1] It is a type of field goal that is worth two points. Such a shot was known as a "dunk shot"[1] until the term "slam dunk" was coined by former Los Angeles Lakers announcer Chick Hearn.[2]

The slam dunk is usually the highest percentage shot[3] and a crowd-pleaser. Thus, the maneuver is often taken from the basketball game and showcased in slam dunk contests such as the NBA Slam Dunk Contest held during the annual NBA All-Star Weekend. The first incarnation of the NBA Slam Dunk Contest was held during the half-time of the 1976 ABA All-Star Game.

A study was carried out in 2015 to show the effectiveness of different shot types, including slam dunks. The study was carried out across five different levels of basketball (NBA, EuroBasket, the Slovenian 1st Division, and two minor leagues). Overall the study showed that slam dunks were a very effective way of scoring in the game of basketball, particularly in the NBA, which had the highest dunk percentage in the study.[4]

History

[edit]Joe Fortenberry, playing for the McPherson Globe Refiners, dunked the ball in 1936 in Madison Square Garden. The feat was immortalized by Arthur Daley, Pulitzer Prize winning sports writer for The New York Times in an article in March 1936. He wrote that Joe Fortenberry and his teammate, Willard Schmidt, instead of shooting up for a layup, leaped up and "pitch[ed] the ball downward into the hoop, much like a cafeteria customer dunking a roll in coffee".[5][6][7]

During the 1940s, 7-foot center and Olympic gold medalist Bob Kurland was dunking regularly during games.[8] Yet defenders viewed the execution of a slam dunk as a personal affront that deserved retribution; thus defenders often intimidated offensive players and thwarted the move. Kurland's rival big man George Mikan noted "We used to dunk in pregame practice, not in the game." Satch Sanders, a career Boston Celtic from 1960 to 1973, said: "in the old days, [defenders] would run under you when you were in the air ... trying to take people out of games so they couldn't play. It was an unwritten rule."[9]

Still, by the 1950s and early 1960s some of the NBA's tallest and strongest centers such as Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain had incorporated the move into their offensive arsenal. Slightly smaller players at forward and guard then began to dunk, helping to popularize the move, like "Jumping" Johnny Green, Gus Johnson, Elgin Baylor, and Connie Hawkins in the 1960s and David Thompson and Julius Erving in the 1970s. This transformed dunking into the standard fare it is today.

1956 rule changes

[edit]

In the 1950s, Jim Pollard[10] and Wilt Chamberlain[11] had both dunked from the free throw line—15 feet from the basket. Chamberlain was able to dunk from the free-throw line without a running start, beginning his forward movement from within the top half of the free-throw circle.[11] This was the catalyst for the 1956 NCAA rule change which requires that a shooter maintain both feet behind the line during a free-throw attempt.[12] An inbounds pass over the backboard was also banned because of Chamberlain.[13] Offensive goaltending, also called basket interference, was introduced as a rule in 1956 after Bill Russell had exploited it at San Francisco and Chamberlain was soon to enter college play.[14] While at the University of Kansas, Chamberlain was known to have dunked on an experimental 12-foot basket set up by Phog Allen.[11][a] When Chamberlain dunked the ball it was called a "dipper dunk."

Lew Alcindor rule

[edit]Dunking was banned in the NCAA and high school sports from 1967 to 1976.[17][18][19] Many people have attributed the ban to the dominance of the college phenomenon Lew Alcindor (now known as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar);[20] the no-dunking rule is sometimes referred to as the "Lew Alcindor rule."[21][22] Others have attributed the ban to racial motivations, as at the time most of the prominent dunkers in college basketball were African-American, and the ban took place less than a year after the 1966 NCAA University Division basketball championship game, wherein a Texas Western team with an all-black starting lineup beat an all-white Kentucky team to win the national championship.[23] Under head coach Guy Lewis, Houston (with Elvin Hayes) made considerable use of the "stuff" shot on their way to the Final Four in 1967.[24]

Breakaway rims

[edit]

In the NBA, in 1976 Arthur Erhat filed a patent for "a rim that had give but immediately returned to its original position," making dunking safe for the first time by significantly reducing the shattering of backboards.[25][26] In 1979, Erving's teammate and center Darryl Dawkins twice shattered NBA backboards with dunks leading to a quickly-enacted rule making it an offence to break the backboard.[citation needed] Technology has evolved to adapt to the increased strength and weight of players to withstand the force of such dunks, such as the breakaway rim (introduced to the NBA in 1981) changes to the material used for the backboards, and strengthening of the goal standards themselves. The invention by Arthur Ehrat to create the breakaway rim with a spring on it led to the return of the dunk in college basketball.[26]

All-star power forward Gus Johnson of the Baltimore Bullets was the first of the famous backboard breakers in the NBA, shattering three during his career in the 1960s and early 1970s.[27][b] Luke Jackson also shattered a backboard in 1968.[28] In the ABA, Charlie Hentz broke two backboards in the same game on 6 November 1970 resulting in the game being called.[29][c]

The NBA has made shattering the backboard a technical foul, although it will not count towards a player's count of seven that can draw a suspension, or two towards ejection from a game, though it counts towards a player's count of six personal fouls. This has assisted in deterring this action, as it can cost the team points.

Slam Dunk Contest era

[edit]The first-ever Slam Dunk Contest was held on January 27, 1976 at McNichols Sports Arena in Denver during halftime of the 1976 ABA All-Star Game, the league's final All-Star game before the completion of the ABA–NBA merger.[30] Erving defeated Thompson in the championship round, after leaping from the free-throw line. The other participants were Artis Gilmore, George Gervin, and Larry Kenon.

The NBA held its first Slam Dunk Contest as a one-off, season-long event similar to NBA Horse event held the following season.[31][32] During halftime at each game, there was a one-on-one slam dunk competition.[33] Former ABA player Darnell "Dr. Dunk" Hillman was named the winner that season. Although he received the winner's $15,000 check, Hillman did not receive a trophy until 2017.[32][34]

Modern era

[edit]The Houston Cougars from 1982 to 1984, with Hakeem Olajuwon and Clyde Drexler, were known as Phi Slama Jama. The national champion 1982 North Carolina Tar Heels also featured two notable dunkers: James Worthy and Michael Jordan.

Larry Nance won the first modern dunk contest in 1984. Spud Webb at 5 ft 7 in (1.70 m) defeated 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m) Dominique Wilkins in the 1986 dunk contest.

Michael Jordan nicknamed "Air Jordan" for his dunking ability, popularized a dunk referred to by some fans as the "Leaner" in 1987 contest. This dunk was so called because Jordan's body was not perpendicular to the ground while performing the dunk. TNT viewers rated it "the best dunk of all time" over Vince Carter's between-the-legs slam.[citation needed] In the 1988 NBA Slam Dunk Contest, which came down to Michael Jordan and Dominique Wilkins, Jordan dunked from the free-throw line, much like Erving, but parted his legs making his dunk arguably more memorable than Erving's.

Twice in his rookie season (1992–93) during games, center Shaquille O'Neal dunked so hard that he broke the hydraulic support of one goal standard (against the Phoenix Suns) and broke the welds holding up another goal standard, causing the basket to break off and fall to the floor (against the New Jersey Nets), although in neither case did the glass break. This resulted in reinforced backboard supports as well. During that same season, New Jersey's Chris Morris shattered a backboard in a game against the Chicago Bulls (the most recent shattered-backboard incident in the NBA to date).

In the 1996 NBA Slam Dunk Contest, winner Brent Barry dunked from the free-throw line. Barry received 49 (out of 50) for the dunk.[35] Kobe Bryant won the 1997 Dunk Contest.

2000–present

[edit]Vince Carter dunked while leaping over 7-foot-2 (2.18 m) French center Frédéric Weis in the 2000 Summer Olympics. The French media dubbed it "le dunk de la mort"—"the dunk of death".[36][37] In the 2000 dunk contest Carter used an elbow hang along with his reverse 360 windmill dunk (reminiscent of Kenny Walker's 360 windmill dunk in 1989 except that Carter spins clockwise, whereas Walker spins counter-clockwise) and between-the-legs dunk. When performed, much of the audience was speechless, including the judges, because none had seen these types of dunks before.

In the 2008 Sprite Rising Star's Slam Dunk Contest Dwight Howard performed the "Superman" dunk. He donned a Superman outfit as Orlando Magic guard Jameer Nelson tied a cape around his shoulders. Nelson alley-ooped the basketball as Howard jumped from within the key side of the free throw circle line, caught the ball, and threw it through the rim. This dunk is somewhat controversial, as his hand was not over as well as on a vertical plane to the rim. Some insist that it should in fact be considered a dunk because the ball was thrust downward into the basket, meeting the basic definition of the dunk.

During the 2009 NBA dunk contest, Howard had a separate goal brought onto the court, and the rim was noticeably significantly higher than a standard goal. Howard, after going into a 1950s-era telephone booth and again fashioning the Superman attire, caught a pass from Nelson and easily completed a two-handed dunk on the higher goal. While this was not performed for record-setting purposes, the dunk received a perfect score and a warm response from the crowd, in part because of its theatrics. Also in this contest, 5'9" guard Nate Robinson wore a green New York Knicks jersey and green sneakers to represent Kryptonite, playing on Howard's Superman theme. He used a green "Kryptonite" ball, and jumped over the 6'11" Howard prior to dunking. This dunk and the theatrics could have won the competition for Robinson, who was voted the winner by the NBA fans. Robinson then thanked Howard for graciously allowing him to dunk over him, asking the crowd to also give Howard a round of applause.

More recently, the Clippers earned the nickname "Lob City" from 2011 onwards, with Chris Paul utilizing alley-oop passes regularly to teammates Blake Griffin, and DeAndre Jordan.

JaVale McGee currently holds the world record for Most Basketball Dunks in a Single Jump: three. While competing in the 2011 NBA Sprite Slam Dunk Contest, McGee jumped with two balls in his possession and dunked each prior to receiving and slamming an alley-oop pass from then teammate John Wall.[38]

In the 2016 NBA Slam Dunk Contest, Zach LaVine dunked from the free throw line on three occasions: One Hand, Windmill, and Between the Legs. All of the Dunks received a score of 50 for the dunk and won the Dunk contest.

Dunk types

[edit]Dunk types reflect the various motions performed on the way to the basket. They start with the basic one- or two-hand forward-facing dunk and go on through various levels of athleticism and intricacy. Discrete dunk types can be modified by appending other moves; for example, a player who passes the ball off the backboard, catches it in the air, and executes a double-pump dunk would be said to have completed a "self-pass off the backboard, double pump".

Tomahawk

[edit]

One of the simplest dunk types is the "tomahawk" dunk, resembling the windup and sharp downward motion of a blow with a tomahawk. A tomahawk dunk can be performed with one or two hands, and when two hands are used, it is called a backscratcher. Initially referred to as a gorilla dunk,[39] that term is uncommon now. During the jump, the ball is raised above, and often behind the player's head for a wind-up before slamming the ball down into the net at the apex of the jump. Due to the undemanding body mechanics involved in execution, the tomahawk is employed by players of all sizes and jumping abilities.[citation needed] Because of the ball-security provided by the use of both hands, the two-handed tomahawk is a staple of game situations—frequently employed in alley-oops and in offense-rebound put-back dunks.

In one common variation, a 360° spin may be completed prior to or simultaneously with the tomahawk. Circa 2009, independent slam dunker Troy McCray pioneered an especially complex variant of the dunk: once the tomahawk motion is complete, instead of slamming the ball in the rim, a windmill dunk (see below) is then performed.[40]

Windmill

[edit]Before takeoff, or at the onset of the jump, the ball is brought to the abdomen and then the windmill motion is started by moving the ball below the waist according to the length of the player's fully extended arm. Then following the rotation of the outstretch arm, the ball is moved in a circular motion, typically moving from the front towards the back, and then slammed through the rim. Although, due to momentum, many players are unable to palm the ball through the entire windmill motion, the dunk is often completed with one-hand as centripetal force allows the player to guide the ball with only their dunking hand. In some instances sticky resins or powders may be applied to the palm, these are thought to improve grip and prevent loss of possession.[41] Amongst players, subtle variations in the direction of the windmill depend on bodily orientation at takeoff and also jumping style (one-foot or two-feet) in relation to dominant hand.

There are a number of variations on the windmill, the most common being the aforementioned one- or two-hand variants. In these cases, the windmill motion may be performed with the previously discussed one-arm technique and finished with one- or two-hands, or the player may control the ball with two hands, with both arms performing the windmill motion, finishing with one or both hands. Additionally, the ball may be cuffed between the hand and the forearm—generally with the dominant hand. The cuff technique provides better ball security, allowing for a faster windmill motion and increased force exerted on the basket at finish, with either one or both hands. Using the cuffing method, players are also afforded the opportunity of performing the windmill motion towards the front, a technique exploited by French athlete Kadour Ziani when he pioneered his trademark double-windmill.

Occasionally in the game setting, the windmill is performed via alley-oop but is rarely seen in offense-rebound putback dunks due to the airtime required. Dominique Wilkins popularized powerful windmills—in games as well as in contests—including two-handed, self-pass, 360°, rim-hang, and combined variants thereof.

Double Clutch

[edit]At the onset of the jump, the ball is controlled by either one or both hands and once in the air is typically brought to chest level. The player will then quickly thrust the ball downwards and fully extend their arms, bringing the ball below the waist. Finally the ball is brought above the head and dunked with one or both hands; and the double clutch appears as one fluid motion. As a demonstration of athletic prowess, the ball may be held in the below-the-waist position for milliseconds longer, thus showcasing the player's hang time (jumping ability).

Whether the result of a 180° spin or body angle at takeoff, the double clutch is generally performed with the player's back toward the rim. While this orientation is rather conducive to the double clutch motion, Spud Webb was known to perform this dunk while facing the basket. Additionally, Kenny "Sky" Walker, Tracy McGrady—in the 1989 and 2000 NBA Contests, respectively—and others, have performed 360° variation of the double clutch (McGrady completed a lob self-pass before the dunk). Circa 2007, independent slam dunker T-Dub performed the double clutch with a 540° spin which he concluded by hanging on the rim.[42]

Between the Legs

[edit]For one-footed jumpers, the ball is generally transferred to the non-dominant hand just before or upon take-off; for two-footers, this transfer is often delayed for milliseconds as both hands control the ball to prevent dropping it. Once airborne, the dunker generally transfers the ball from non-dominant to dominant hand beneath a raised leg. Finally, the ball is brought upwards by the dominant hand and slammed through the rim.

The between-the-legs dunk was popularized by Isaiah Rider in the 1994 NBA slam dunk contest, who called it "The East Bay Funk Dunk,"[43] so much so that the dunk is often colloquially referred to as a "Rider dunk"—notwithstanding Orlando Woolridge's own such dunk in the NBA contest a decade earlier.[44] Since then, the under-the-leg has been attempted in the NBA contest by a number of participants, and has been a staple of other contests as well. Its difficulty—due to the required hand-eye coordination, flexibility, and hang-time—keeps it generally reserved for exhibitions and contests, not competitive games. Ricky Davis has managed to complete the dunk in an NBA game,[45] but both he[46] and Josh Smith[47] have botched at least one in-game attempt as well.

Because of the possible combinations of starting and finishing hands, and raised-legs, there are many variations on the basic under-the-legs dunk—more so than any other.[48] For example, in a 1997 French Dunk contest, Dali Taamallah leapt with his right leg while controlling the ball with his left hand, and once airborne he transferred the ball from his left hand, underneath his right leg to his right hand before completing the dunk.[49] NBA star Jason Richardson has also pioneered several notable variations of the between-the-legs including a lob-pass to himself[50] and a pass off of the backboard to himself.[51] Independent athlete Shane 'Slam' Wise introduced a cuffed-cradle of the ball prior to initiating the under the leg transfer and finishing with two-hands.[52] While a number of players have finished the dunk using one- or two-hands with their backs to the rim, perhaps the most renowned variant of the dunk is the combination with a 360°, or simply stated: a 360-between-the-legs. Due to the athleticism and hang-time required, the dunk is a crowd favorite and is heralded by players as the preeminent of all dunks. The dunk was once done by Zach LaVine during the 2015 Slam Dunk Contest, which he called the “Space Jam Dunk”.

Elbow Hang

[edit]The player approaches the basket and leaps as they would for a generic dunk. Instead of simply dunking the ball with one or two hands, the player allows their forearm(s) to pass through the basket, hooking their elbow pit on the rim before hanging for a short period of time. Although the dunk was introduced by Vince Carter in the 2000 NBA Slam Dunk contest, Kobe Bryant was filmed performing the dunk two years earlier in 1998 at an exhibition in the Philippines[53] and during the 1997 offseason at Magic Johnson's A Midsummer Night's Magic charity event as well as Roy Hinson who performed the dunk during warm-ups for the 1986 NBA Slam Dunk contest.[54] Colloquially, the dunk has a variety of names including 'honey dip', 'cookie jar', and 'elbow hook'.

In the 2011 NBA contest, Los Angeles Clippers power-forward Blake Griffin completed a self-pass off of the backboard prior to elbow-hanging on the rim. A number of other variants of the elbow hang have been executed, including a lob self-pass, hanging by the arm pit,[55] a windmill,[56] and over a person.[57] Most notable are two variations which as of July 2012, have yet to be duplicated. In 2008, Canadian athlete Justin Darlington introduced an iteration aptly entitled a 'double-elbow hang', in which the player inserts both forearms through the rim and subsequently hangs on both elbows pits.[58] Circa 2009, French athlete Guy Dupuy demonstrated the ability to perform a between-the-legs elbow hang; however, Guy opted not to hang on the rim by his elbow, likely because the downward moment could have resulted in injury.[59]

Alley-oop

[edit]An alley-oop dunk, as it is colloquially known, is performed when a pass is caught in the air and then dunked. The application of an alley-oop to a slam dunk occurs in both games and contests. In games, when only fractions of a second remain on the game or shot clock, an alley-oop may be attempted on in-bound pass because neither clock resumes counting down until an in-bounds player touches the ball. The images to the right depict an interval spanning 1/5 of a second.

Other

[edit]James White in the 2006 NCAA Slam Dunk Contest successfully performed tomahawk and windmill variations of the foul-line dunk.[60] Though he was unable to complete a between-the-legs from the foul line at that contest, he has been known to execute it on other occasions.[61]

In the 2008 NBA Slam Dunk Contest, Jamario Moon leaped from the foul-line then, using his non-dominant hand, caught and dunked a bounce-pass from teammate Jason Kapono.[62]

Independent 6'2" North American athlete Eric Bishop introduced a dunk entitled the 'Paint Job'. The title is in reference to the key on a basketball court, often known as 'paint' in common parlance.[63] Approaching along the baseline with a running dribble, Bishop jumped with one-foot at the border of the key, dunked with one-hand while gliding over the key and landed just beyond the border on the side opposite his take-off—a 16-foot flight.

At least one player has performed a 720 degree dunk (that is, two full turns in the air): Taurian Fontenette also known as Air Up There during a Streetball game.[64]

Dunking in women's play

[edit]

Dunking is much less common in women's basketball than in men's play. Dunking is slightly more common during practice sessions, but many coaches advise against it in competitive play because of the risks of injury or failing to score.[65]

In 1978, Cardie Hicks became the first woman to dunk in a professional game[66] during a men's professional game in the Netherlands.

In 1984, Georgeann Wells, a 6'7" (201 cm) junior playing for West Virginia University, became the first woman to score a slam dunk in women's collegiate play, in a game against the University of Charleston on 21 December.[67] On December 4, 1994, Charlotte Smith, then a member of the UNC Tar Heels women's basketball team, became the second collegiate women's player ever to dunk.[68]

As of 2024, at least 37 dunks have been scored by 8 different WNBA players. The first and second were scored by Lisa Leslie of the Los Angeles Sparks, on 30 July 2002 (against the Miami Sol), and 9 July 2005. Other WNBA dunks have been scored by Michelle Snow (first during an All-Star game), Candace Parker (twice), Sylvia Fowles, Brittney Griner, Jonquel Jones, Liz Cambage, and Awak Kuier.[69][70]

The record for the most WNBA dunks belongs to Brittney Griner, with 25 career dunks as of 2024.[71] Griner was also the first player to dunk twice in one game (27 May 2013, her WNBA debut) and the first to dunk in a playoff game (25 August 2014).[72][73] Griner was also prolific in high school and college: as a high school senior, she dunked 52 times in 32 games and set a single-game record of seven dunks.[74] As a standout at Baylor University, Griner became the seventh player to dunk during a women's college basketball game[75] and the second woman to dunk twice in a single college game.[76]

At the 2012 London Olympics, Liz Cambage of the Australian Opals became the first woman to dunk in the Olympics, scoring against Russia.[77]

Women in dunk contests

[edit]In 2004, as a high school senior, Candace Parker was invited to participate in the McDonald's All-American Game and accompanying festivities where she competed in and won the slam dunk contest.[78] In subsequent years other women have entered the contest; though Kelley Cain, Krystal Thomas, and Maya Moore were denied entry into the same contest in 2007.[79] Brittney Griner intended to participate in the 2009 McDonald's Dunk Contest but was unable to attend the event due to the attendance policy of her high school.[80] Breanna Stewart, at 6'3" (191 cm), Alexis Prince (6'2"; 188 cm), and Brittney Sykes (5'9"; 175 cm) competed in the 2012 contest; Prince and Sykes failed to complete their dunks, while Stewart landed two in the first round but missed her second two attempts in the final round.[81][82]

Use as a phrase

[edit]

One of many sports idioms, the phrase "slam dunk" is often used outside of basketball to refer colloquially to something that has a certain outcome or guaranteed success (a "sure thing").[83] This is related to the high probability of success for a slam dunk versus other types of shots. Additionally, to "be dunked on" or to get "posterized" is sometimes popularly used to indicate that a person has been easily embarrassed by another, in reference to the embarrassment associated with unsuccessfully trying to prevent an opponent from making a dunk. This ascension to popular usage is reminiscent of, for example, the way that the baseball-inspired phrases "step up to the plate" and "he hit it out of the park," or American football-inspired phrases such as "victory formation" or "hail Mary" have entered popular North American vernacular.

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Michael Wilson, a former Harlem Globetrotter and University of Memphis basketball player, matched this feat on 1 April 2000 and got into the Guinness World Records, albeit with an alley-oop.[15][16]

- ^ In one game, Chamberlain dislocated the shoulder of Johnson by blocking his dunk attempt.

- ^ In the NCAA, Jerome Lane shattered a backboard while playing for Pitt in a 1988 regular-season game against Providence, and Darvin Ham did the same while playing for Texas Tech in a tournament game against North Carolina in 1996. The Premier Basketball League has had two slam-dunks that have resulted in broken backboards. Both came consecutively in the 2008 and 2009 PBL Finals, and both were achieved by Sammy Monroe of the Rochester Razorsharks.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Merriam-Webster refers the term "slam dunk" to the term "dunk shot", which is defined as "a shot in basketball made by jumping high into the air and throwing the ball down through the basket". M-W dates "slam dunk" at 1972, and "dunk shot" as "circa 1961".

- ^ sportsillustrated.com, Lakers announcer Hearn dead at 85. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ^ One Way to Play Basketball. United States: Beta Books, 1977.

- ^ Erčulj, F. (2015). Basketball Shot Types and Shot Success in Different Levels of Competitive Basketball. PLOS One, e0128885.

- ^ Demirel, Evin (15 February 2014). "The First Dunk in Basketball". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ "The Creighton giant who helped invent the slam dunk," June 29, 2021, from Creighton at the Olympics, Creighton University, retrieved September 22, 2025

- ^ Chandler, Chip: "Amarillo man to be featured on 'Antiques Roadshow' with history-making gold medal," January 16, 2017 (last modified February 13, 2020), Panhandle PBS, Public Broadcasting System, retrieved September 22, 2025

- ^ Jackie, Krentzman (12 February 1996), "Jam boree - basketball's dunk shot; includes related articles", The Sporting News, archived from the original on 29 June 2012

- ^ NBA Jam Session: A Photo Salute to the NBA Dunk. History. Page 22. 1993, NBA Publishing.

- ^ The Official NBA Basketball Encyclopedia. Villard Books. 1994. p. 49. ISBN 0-679-43293-0.

- ^ a b c Ostler, Scott (12 February 1989). "The Leaping Legends of Basketball". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "That Stilt, Wilt, Responsible For 2 Rule Changes; Kansas' Chamberlain Even Dunked His Foul Shots", Toledo Blade, 28 November 1956

- ^ Aram Goudsouzian (2005). ""Can Basketball Survive Chamberlain"" (PDF). Kansas History.

- ^ Ralph Miller (1990). Spanning the Game. Sagamore Pub. p. 193. ISBN 9780915611386.

- ^ Warner, Ralph; Martinez, Jose (29 February 2012). "High Risers: Athletes With the Best Hops in Sports HistoryMichael Wilson". Complex. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Butler, Robbie (2001). The Harlem Globetrotters : Clown princes of basketball. Mankato, MN: Capstone Press. p. 36. ISBN 073684001X. OCLC 47045255.

- ^ "Dunk Shot Is Ruled Out of the Game", Indianapolis Star, March 29, 1967, p. 29

- ^ "The dunk is coming back". Eugene Register-Guard. Oregon. Associated Press. 1 April 1976. p. 1C.

- ^ Doney, Ken (1 April 1976). "'They'll love dunk' - Miller". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. Associated Press. p. 2B.

- ^ "Slam dunk: most welcome it". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. Associated Press. 2 April 1976. p. 2B.

- ^ time.com, Lew's Still Loose. Retrieved 15 April 2007.

- ^ Caponi, Gena (1999). Signifyin(G), Sanctifyin', & Slam Dunking. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-55849-183-0.

- ^ "When college basketball outlawed the dunk". 23 March 2014.

- ^ "Houston cage coach advocates stuff shot". Eugene Register-Guard. Oregon. Associated Press. 24 March 1967. p. 3B.

- ^ Greene, Nick (1 April 2015). "A Brief History Of The Slam Dunk". Mental Floss. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ a b Keilman, John and Tribune staff reporter - This gadget really was a slam-dunk. Chicago Tribune, April 4, 2005

- ^ Goldaper, Sam (30 April 1987). "Gus Johnson, Ex-N.B.A. Star with Baltimore, is Dead at 48". The New York Times.

- ^ Milwaukee Sentinel. 12 November 1968.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ "A Roundup Of The Sports Information Of The Week". Sports Illustrated. 16 November 1970. Archived from the original on 6 October 2008.

- ^ Sheehan Jr, Vinny (16 February 2018). "Reliving the first Slam Dunk Contest with David Thompson". Pack Pride. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "Dr. Dunk Rates His Competition". NBA.com.

- ^ a b Medworth, Whitney (8 March 2017). "Darnell Hillman won the NBA dunk contest in 1977. He finally got his trophy". SBNation.com. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ Dwyer, Kelly (9 March 2017). "1977 NBA Slam Dunk champ Darnell Hillman is finally given a trophy, 40 years later". sports.yahoo.com. Retrieved 18 July 2022.

- ^ "For Dunk Contest: Hillman Shirt Different". The Victoria Advocate. 12 June 1977. pp. 5C. Retrieved 18 July 2022 – via Google News.

- ^ 1996 Brent Barry Dunk From The Freethrow Line

- ^ Wallace, Michael; Peterson, Rob (25 September 2015). "In a single bound: Oral history of Vince Carter's greatest dunk". ESPN. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ Gould, Andrew (15 February 2018). "Relive Vince Carter's Iconic Dunk over Frederic Weis in the 2000 Olympics". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ^ "Most basketball dunks in a single jump". 19 February 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ^ EA Sports (1989), Lakers versus Celtics and the NBA Playoffs Electric Arts Video Game, retrieved 21 March 2022

- ^ 101Retro - Troy McCray. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "JUMPUSA.com: Stickum Grip Powder". Archived from the original on 6 June 2012. Retrieved 21 May 2012.

- ^ "YouTube: T-Dub Dunks". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 22 May 2012. Fast-forward to 00:09 in the video.

- ^ "Isiah Rider's Between-the-Legs Dunk". YouTube. Archived from the original on 5 June 2010. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Orlando Woolride :: 1984 between-the-legs dunk". YouTube. Archived from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Rick Davis between the legs". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Ricky Davis failed dunk". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Josh Smith misses between the legs dunk". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ For both one- and two-footed jumper there are four possible between-the-legs and finishing-hand combinations.

- ^ "Flying 101 :: Dunk Encyclopedia -- Taamallah". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Jason Richardson Lob reverse BTL". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Jason Richardson". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Flying 101 :: Dunk Encyclopedia :: Cradle BTL". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Kobe Bryant Elbow hang dunk". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ "Roy Hinson - Elbow Dunk Pioneer (1986 Dunk Contest Warmups)". YouTube. 16 February 2019. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 7 November 2020.

- ^ "Armpit hanging on the rim dunk". YouTube. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- ^ "Haneef Munir Windmill Elbow hang". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ "Kenny Dobbs Slam Interview (half way down page)". Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ "2008 City Slam High lights @ 04:24". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ "TFB :: Guy Dupuy dunks (@ 02:00)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2012.

- ^ "James White 06 NCAA Slam Dunk Contest". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "James White free-throw line between the legs @ 04:50". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "Jamario Moon @ 03:01". YouTube. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- ^ "Dunk Encyclopedia :: Paint Job". YouTube. Archived from the original on 11 December 2021. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Video, Dunk. "720 Dunk by "The Air Up There"". Notable Dunks. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ Palmer, Brian (23 March 2012). "Below the Rim: Why are there so few dunks in women's basketball?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ^ "Pioneers Cardte Hicks, Musiette McKinney embrace Las Vegas Aces". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- ^ wsj.com, The First Dunk: A Sports Milestone in Women's Basketball. Retrieved 9 October 2009.

- ^ "Pioneer Dunker, Lady Tar Heel Charlotte Smith". Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ^ "Which WNBA Player Has the Maximum Dunks in League History?". EssentiallySports. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "WNBA players who can dunk: Brittney Griner stands alone in 2024 with record-setting rim prowess". SportingNews. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "Brittney Griner dunks for first time this season in Mercury win". ESPN. 9 July 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "Griner Dunks Twice In WNBA Debut". CBSNews. 28 May 2013. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ "Watch Brittney Griner slam down the first dunk in WNBA playoff history". For The Win. 25 August 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "Baylor University || the Lariat Online || News". www.baylor.edu. Archived from the original on 19 July 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ "Griner Dunks Twice in WBB's 99-18 Win". Baylorbears.com. 2 January 2010. Archived from the original on 26 January 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2010.

- ^ Brittney Griner dunks twice, Baylor wins by 81 (video).

- ^ "VIDEO: First dunk by female player in Olympics history". www.cbssports.com. 3 August 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2024.

- ^ McDonald's All-American Game#Sprite/Powerade Jam Fest Award Winners McDonald's All-American Game :: Past Slam Dunk Contest winners at Wikipedia

- ^ "Scout.com: Girls Can't Dunk?". Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012. Article at GirlsHoops.com about the Ladies being denied participation in the '07 Contest.

- ^ "Hoop Gurlz: Griner isn't allowed to attend McDonald's game". ESPN.com. 2 March 2009. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20200114171749/http://www.mcdonaldsallamerican.com/2012JamFestResults.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Video: Breanna Stewart dunks twice during Powerade Jam Fest dunk championship". Archived from the original on 13 October 2012.

- ^ "He Shoots, He Scores; She Shoots, She Scores. 'Slam Dunk' Terms Resound"[dead link]. Voice of America News. 14 March 2007

External links

[edit]Slam dunk

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Fundamentals

Technical Definition

A slam dunk, also known simply as a dunk, is a type of field goal in basketball wherein an offensive player leaps into the air and propels the ball downward through the hoop using one or both hands, with the player's hand or hands positioned above the horizontal plane of the rim at the moment of release.[8] This action requires the ball to be forced or thrust aggressively into the basket, distinguishing it from softer layups or tip-ins that enter the hoop without such downward momentum.[9] In official rules, such as those of FIBA, a dunk is explicitly defined as forcing the ball downward into the basket with one or both hands, typically as part of a continuous motion during a drive or jump shot.[9] The technique scores two points in standard play (or three if attempted from beyond the three-point arc, though rare due to the mechanics involved), and it is scored as a successful field goal provided the ball passes cleanly through the net without violating goaltending rules on defense.[10] Unlike other shots, the slam dunk emphasizes vertical elevation and power, often executed off a fast break, alley-oop pass, or isolation drive, with the player's wrist flick minimized in favor of raw arm extension and grip on the ball.[2] Historical terminology evolved from "dunk shot" to "slam dunk" by the mid-20th century, reflecting the emphatic, rim-rattling nature of the play popularized in professional leagues.[8]Physical Requirements

The slam dunk necessitates elevating the body such that the hand gripping the basketball can forcefully drive the ball downward through the rim from above. Regulation rim height, as standardized by the NBA and FIBA, measures 10 feet (3.05 meters) from the playing surface to the upper edge of the ring.[11] [12] Required vertical displacement varies primarily with standing reach, defined as the height from floor to the fingertips of an extended arm in a flat-footed stance, which averages approximately 1.3 times the player's height.[13] For a typical 6-foot (1.83 m) male athlete with a standing reach of 7 feet 10 inches (2.39 m), a vertical leap of 28 to 34 inches (71 to 86 cm) enables the wrist to clear the rim while accommodating the basketball's 9.4-inch (24 cm) diameter and necessary overhead positioning.[14] Shorter individuals face steeper demands; a 5-foot 10-inch (1.78 m) player often requires at least 32 inches (81 cm), while those under 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 m) typically need 36 inches (91 cm) or more.[15] Explosive power underpins this elevation, relying on rapid force production from the lower extremities—quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes, and calves—to exceed body weight in ground reaction forces during takeoff.[16] Biomechanical analyses highlight the role of one- or two-footed jumps, where horizontal approach velocity converts to vertical momentum, amplifying peak height beyond pure countermovement jumps.[17] Core stability prevents torso rotation in flight, preserving alignment for accurate execution, while sufficient upper-body strength facilitates arm extension and ball control against inertial forces.[18] Hand size and grip strength further influence feasibility, as larger palms allow better ball security during descent.[19] In basketball cohorts, vertical jumps correlating with dunk proficiency range from 24 to 42 inches (61 to 107 cm), with elite performers leveraging fast-twitch fiber dominance for repeated efforts.[20]Physics and Biomechanics

Jump Mechanics and Vertical Leap

The vertical leap represents the explosive height differential between a player's standing reach and peak jump elevation, essential for slam dunks as it enables the hand to extend 6-12 inches above the 10-foot (3.05 m) rim to grip and force the ball through the hoop.[21] In basketball, effective dunking typically requires a running vertical leap of 28-36 inches (71-91 cm) for players of average height and arm length, though this varies with individual anthropometrics such as standing reach, which averages around 8 feet (2.44 m) for NBA prospects.[21] Running starts convert horizontal momentum into vertical propulsion, yielding 4-8 inches greater height than standing jumps due to enhanced impulse generation.[22] Jump mechanics in slam dunks emphasize the stretch-shortening cycle during the countermovement phase, where eccentric muscle loading (rapid deceleration and squat) precedes concentric explosion (hip, knee, and ankle extension), optimizing elastic energy storage in tendons and muscles for maximal takeoff velocity.[23] Primary contributors include quadriceps, glutes, and calves generating peak ground reaction forces exceeding 3-5 times body weight within minimal ground contact time (0.2-0.3 seconds), with core stability preventing energy loss.[24] Arm swing and trunk lean further augment upward impulse by counterbalancing and adding momentum. In two-foot running vertical jumps relevant to many dunks, biomechanical analyses identify initial forward center-of-mass velocity, shallow plant angle (promoting anterior foot positioning for momentum redirection), center-of-mass ascent distance during loading, and net upward/backward impulses as key positive correlates to jump height (correlation coefficients 0.533-0.966, p < 0.05).[25] One-foot takeoffs, common in high-speed dunks, prioritize unilateral power and quicker plant but may sacrifice force magnitude compared to bilateral efforts, influencing technique selection based on player speed and strength profiles.[26] Overall, vertical leap optimization hinges on power-to-weight ratio, where force production scaled to velocity yields takeoff speeds determining height via h = v²/(2g).[27]Forces, Hang Time, and Power Dynamics

The propulsion phase of a slam dunk requires generating substantial vertical ground reaction forces (GRF) through explosive lower-body extension, primarily involving the quadriceps, glutes, and calves to overcome gravity and achieve takeoff velocity. Peak GRF during basketball dunks typically range from 2 to 4 times body weight, depending on the dunk type and athlete's mass, with impulses creating the necessary momentum for elevation. These forces arise from the rapid conversion of stored elastic energy in tendons and muscles during the countermovement jump, where the athlete first descends slightly before exploding upward, maximizing force application over the short ground contact time of about 0.2-0.3 seconds.[28][29][30] Hang time, the airborne duration from takeoff to landing, follows projectile motion principles under constant gravitational acceleration of 9.81 m/s², with negligible air resistance for jumps under 1 second. The vertical component yields hang time , where is initial vertical velocity; equivalently, for maximum center-of-mass height . Elite performers achieve hang times near 0.9 seconds, as in Michael Jordan's recorded 0.92 seconds during a free-throw line dunk, corresponding to a takeoff velocity of approximately 4.5 m/s and vertical rise over 1 meter, though horizontal velocity in running dunks extends perceived time without altering vertical physics.[31][30] Power dynamics center on the explosive rate of force development, quantified as , where sustained high force combines with limb velocity during push-off to produce work against gravity. In slam dunks, peak power outputs exceed 50 watts per kilogram for top athletes, enabling takeoff speeds of 2.5-4 m/s and rim-contact heights sufficient for forceful ball insertion. This neuromuscular efficiency, honed through plyometric training, dictates dunk feasibility, as insufficient power limits vertical leap below the 0.7-1.0 meter threshold typical for NBA rims at 3.05 meters. Biomechanical analyses confirm that optimizing hip and knee extension power, rather than sheer strength, correlates most with dunking prowess.[30][17]Historical Development

Origins and Early Adoption

The slam dunk, involving a player jumping to insert the ball forcefully through the hoop with one or both hands, emerged in the early decades of organized basketball following its invention in 1891 by James Naismith.[32] Initial rules and equipment, including closed-bottom peach baskets and lower athletic standards among players, discouraged aggressive rim attacks, rendering dunks exceptional rather than routine.[4] The average player height in the sport's formative years hovered around 6 feet, requiring an improbable vertical leap of over 4 feet to reach the 10-foot rim, which limited occurrences to rare physical outliers.[5] The first documented slam dunk in an organized competitive setting is attributed to Joe Fortenberry, a 6-foot-8-inch forward, who performed it during a 1936 exhibition game at Madison Square Garden while preparing for the Berlin Olympics with the U.S. national team.[33] Fortenberry's feat, executed in short shorts amid a demonstration against a local team, marked the initial recorded instance in a structured match, though anecdotal accounts suggest informal dunks may have preceded it in non-competitive play, such as by New York player Jack Inglis in the 1920s using arena wire cages for momentum.[3] These early examples highlighted the dunk's dependence on exceptional stature and leaping ability, as Fortenberry captained the Olympic squad that won gold, showcasing how international exposure began to normalize the maneuver among elite tall athletes.[5] In collegiate basketball, the first verified dunk occurred in 1944 when Bob Kurland, a 6-foot-10-inch center for Oklahoma A&M (now Oklahoma State), accidentally slammed the ball during a game against Temple University.[32] Kurland, known as "Foothills" for his high school origins, repeated the action intentionally thereafter, contributing to his team's undefeated season and two NCAA titles in 1945 and 1946.[32] This period saw gradual adoption as post-World War II player pools included more veterans with physical prowess, though dunks remained infrequent due to coaching emphases on set shots and passing over individual athleticism.[34] By the 1950s, professional leagues like the NBA witnessed increased usage from centers such as George Mikan, but widespread early adoption awaited the influx of even taller, more agile players like Wilt Chamberlain in the late 1950s, who elevated dunking from novelty to strategic weapon.[4]Key Rule Changes and Bans

In 1956, the NCAA prohibited dunking during free throws to counter the dominance of Wilt Chamberlain at the University of Kansas, where he frequently retrieved missed free throws and slammed them through the hoop, gaining an unfair advantage.[35] This rule change, enacted on March 26, 1956, following a proposal two days earlier, marked an early targeted restriction on dunking variants rather than a comprehensive ban.[35] The most significant prohibition occurred in 1967 when the NCAA banned all dunking in college basketball ahead of the 1967-68 season, extending the rule to high school levels until its repeal in 1976.[4] Officially justified by concerns over 1,500 reported injuries near the basket and potential damage to rims, the measure is widely regarded as an attempt to diminish the impact of exceptionally tall and athletic players like Lew Alcindor (later Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), who powered UCLA to three consecutive national championships from 1967 to 1969 using dunks as a core scoring method.[5][36] Alcindor himself criticized the ban as racially motivated, arguing it stifled black athleticism, though NCAA officials denied such intent, emphasizing safety and equipment integrity.[37] The ban's enforcement required officials to disallow any forceful slam, even if the ball passed cleanly through the hoop, leading to technical fouls and altering offensive strategies by forcing taller players to rely on jump shots and layups.[4] It was lifted in 1976 amid improved rim durability and shifting attitudes, coinciding with the retirement of UCLA coach John Wooden, who had opposed the rule but adapted during its tenure.[38] No equivalent bans affected professional leagues like the NBA, where dunking proliferated as a highlight, underscoring differences in regulatory philosophies between amateur and pro basketball.[36]Technological Advancements in Equipment

The development of breakaway rims marked a pivotal advancement in basketball equipment, enabling more forceful and frequent slam dunks without risking structural failure. In 1976, inventor Arthur Ehrat created the first prototype using a hinge mechanism and a heavy-duty spring sourced from agricultural equipment, which allowed the rim to flex downward under impact before returning to position.[39] This design addressed the frequent backboard shattering caused by powerful dunks, such as those by players like Darryl Dawkins, whose slams fractured glass backboards twice during the 1979-80 NBA season.[40] Ehrat's patented invention shifted rims from rigid bolted models to dynamic ones, reducing injury risks from hanging on the hoop and extending equipment durability.[41] Professional leagues rapidly adopted breakaway rims following high-profile incidents. The NBA mandated their use starting in the 1981-82 season, transitioning from fixed rims to standardize safety across venues after Dawkins' dunks highlighted vulnerabilities in traditional setups.[42] Earlier, the NCAA tested breakaway rims in the 1978 Final Four tournament, paving the way for widespread implementation in collegiate and high school play by the early 1980s.[41] These rims, now standard in competitive basketball, incorporate calibrated tension springs—typically bending 6-8 inches under dunk force—to absorb kinetic energy, with rebound times under one second to minimize gameplay disruption.[43] The technology directly facilitated the evolution of dunking styles, as players could execute aggressive, rim-hanging slams without fear of equipment collapse or penalties for damage. Advancements in basketball footwear have also enhanced dunking capabilities through improved energy efficiency and takeoff mechanics. Early 20th-century shoes evolved from basic canvas models, like Converse's 1917 All Star, to leather high-tops providing ankle stability, but by the late 1970s, synthetic materials and cushioning systems reduced weight and fatigue.[44] Nike's Air cushioning, introduced in 1979, used pressurized air pockets in midsoles for superior impact absorption and partial energy return, allowing players to maintain explosive jumps over extended games.[45] Subsequent innovations, including EVA foams, carbon fiber plates, and herringbone traction patterns in the 1980s-2000s, lowered shoe mass by up to 20% compared to prior leather designs while enhancing court grip for rapid acceleration into dunks.[46] Empirical studies indicate these shoe parameters—such as reduced mass, increased midsole flexibility, and stability features—modestly influence vertical jump performance by optimizing biomechanics and comfort, though gains stem primarily from user adaptation rather than inherent propulsion boosts.[47] For instance, lighter outsoles improve ground force application during plantar flexion, correlating with 1-2% higher jump heights in controlled tests, but claims of dramatic increases (e.g., 3.5 inches from specialized tech) lack robust independent verification and often overstate effects beyond placebo or fit improvements.[48] Parallel backboard upgrades, from wire mesh to tempered glass by 1909 and reinforced mounts in the 1970s, complemented these changes by withstanding greater dunk-induced vibrations, further supporting equipment resilience.[36] Overall, these innovations prioritized causal factors like force dissipation and athlete efficiency, enabling dunking to become a safer, more integral aspect of modern play.Slam Dunk Contest Evolution

Inception and Early Years

The NBA Slam Dunk Contest originated from similar events in the American Basketball Association (ABA), which held its first dunk competition during the 1976 All-Star Game in Denver, won by Julius Erving.[49] Following the ABA-NBA merger in 1976, the NBA introduced its own version on February 18, 1984, as part of All-Star Weekend at McNichols Sports Arena in Denver, Colorado, to highlight players' athletic prowess and increase fan engagement.[6][50] The inaugural contest featured participants including Larry Nance, Dominique Wilkins, Ralph Sampson, Orlando Woolridge, and Julius Erving. Phoenix Suns forward Larry Nance won the event, scoring 46 points on his final first-round dunk and defeating Erving in the championship round with a free-throw line dunk.[51][52] In 1985, held in Indianapolis, Atlanta Hawks forward Dominique Wilkins claimed the first of his three titles, edging out Nance in a closely contested final judged on style, creativity, and execution.[53] The 1986 contest in Houston saw an upset when 5-foot-7 Atlanta Hawks guard Spud Webb defeated Wilkins, showcasing that diminutive stature did not preclude spectacular dunking ability.[6][53] Michael Jordan secured back-to-back victories in 1987 and 1988, first in Seattle and then in Chicago, with his 1988 performance including a memorable free-throw line dunk that helped popularize the event globally.[54] Wilkins reclaimed the crown in 1990 in Miami, marking the end of the contest's initial dominant era characterized by high-flying rivalries and innovative dunks that elevated its status within All-Star programming.[53]Judging Controversies and Format Changes

The NBA Slam Dunk Contest has experienced recurrent judging controversies, primarily involving disputes over score consistency, emphasis on first-attempt completions over difficulty, and perceived favoritism toward recognizable players or narratives. In 2006, Nate Robinson's victory over Andre Iguodala in the final round hinged on a tiebreaker where Robinson scored 47 on a dunk judged superior despite Iguodala's displays of greater aerial control and power, leading critics to question the panel's valuation of creativity versus execution.[55] A landmark case unfolded in 2016 between Zach LaVine and Aaron Gordon, where Gordon's final dunk—a between-the-legs reverse over the 7-foot-7 Orlando Magic mascot Stuff—earned 47 and 49 points across rounds, insufficient against LaVine's totals; observers widely argued the dunk's unprecedented risk and spectacle merited perfect 50s, fueling accusations of conservative scoring that undervalued innovation.[55] This pattern repeated for Gordon in 2020 against Derrick Jones Jr., with Gordon losing by one point after a dunk over 7-foot-5 center Tacko Fall, compounded by judge Dwyane Wade's higher scores for Jones amid claims of bias tied to Wade's Heat affiliation.[55] More recently, the 2024 contest between Jaylen Brown and Mac McClung highlighted flaws when Brown's complex second-attempt dunks received sub-50 scores despite their athletic demands, while McClung's cleaner first tries garnered near-perfect marks; analysts attributed this to judges over-prioritizing completion ease, eroding trust in the 0-10 scale's granularity.[56][57] Such incidents reflect broader critiques of judging panels, often comprising celebrities or ex-players, for inconsistent application of criteria like difficulty, style, and power, with calls for decimal precision or contestant-veteran judges to mitigate subjectivity.[58] Format changes have periodically aimed to inject variety and address stagnation or judging opacity, evolving from the 1984 debut's eight-player bracket with three timed dunks per round scored by five judges (totaling up to 150 points) and allowances for botched attempts.[58] Early tweaks included byes for champions (1985-1986), decimal scoring for nuance (1989), and simplified two-dunk rounds with unlimited retries (2005) to reward persistence over perfection.[58] Experimental shifts, such as routine-style judging with clocks (1994-1995), text-voting finals (2008, 2012), and assisted dunks (2000 onward), sought to boost spectacle but drew mixed reception for diluting individual focus.[58] A pivotal alteration came in 2014 with a team-based structure: East and West squads performed in a 90-second freestyle round, followed by head-to-head battles to three wins, won by John Wall's East team but criticized for chaotic pacing and reduced personal stakes, prompting reversion to the classic four-player, two-round individual format in 2015.[59][60] Subsequent iterations retained core elements—two dunks per round, averaged judge scores, top-two advancement—while permitting props and between-the-legs maneuvers to encourage creativity, though without resolving underlying judging tensions.[58] These adjustments underscore efforts to balance tradition with innovation, yet persistent controversies indicate that format alone cannot fully calibrate subjective evaluations.[57]Modern Champions and Recent Developments

The NBA Slam Dunk Contest has featured a series of winners in the 2010s and 2020s who emphasized athletic creativity, often from lesser-known or bench players amid declining participation from superstar athletes. Notable modern champions include Zach LaVine, who secured back-to-back victories in 2015 and 2016 with dunks averaging scores above 45 from judges, highlighted by his between-the-legs reverse slam over a defender.[6] In 2011, Blake Griffin famously dunked over a car parked at the rim, earning a perfect 50 from all judges in the final round and marking one of the event's most viral moments.[54] Subsequent winners like Derrick Jones Jr. in 2020 showcased windmill variations with rim-grabbing flair, while Anfernee Simons claimed the 2021 title with a 360-degree between-the-legs dunk scored at 48.[61]| Year | Winner | Team | Notable Dunk |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Nate Robinson | New York Knicks | Two-handed tomahawk over defender[53] |

| 2011 | Blake Griffin | Los Angeles Clippers | Over-the-hood slam on a Kia sedan[6] |

| 2012 | Jeremy Evans | Utah Jazz | Reverse dunk with free-throw line approach[7] |

| 2013 | Terrence Ross | Toronto Raptors | Eastbay funk dunk tribute to Jason Richardson[6] |

| 2015–2016 | Zach LaVine | Minnesota Timberwolves | Under-the-leg 360 and between-the-legs stunner[54] |

| 2020 | Derrick Jones Jr. | Miami Heat | Rim-hanging windmill[61] |

| 2021 | Anfernee Simons | Portland Trail Blazers | 360 between-the-legs[53] |

| 2022 | Obi Toppin | New York Knicks | Between-the-legs over teammate[6] |

| 2023–2025 | Mac McClung | Various (G-League/Philadelphia 76ers affiliate) | Four perfect 50s in 2025, including over-car jump; first three-peat in history[62][63] |

.jpg/250px-Griner_dunking_at_2015_All-Star_game_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg)