Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

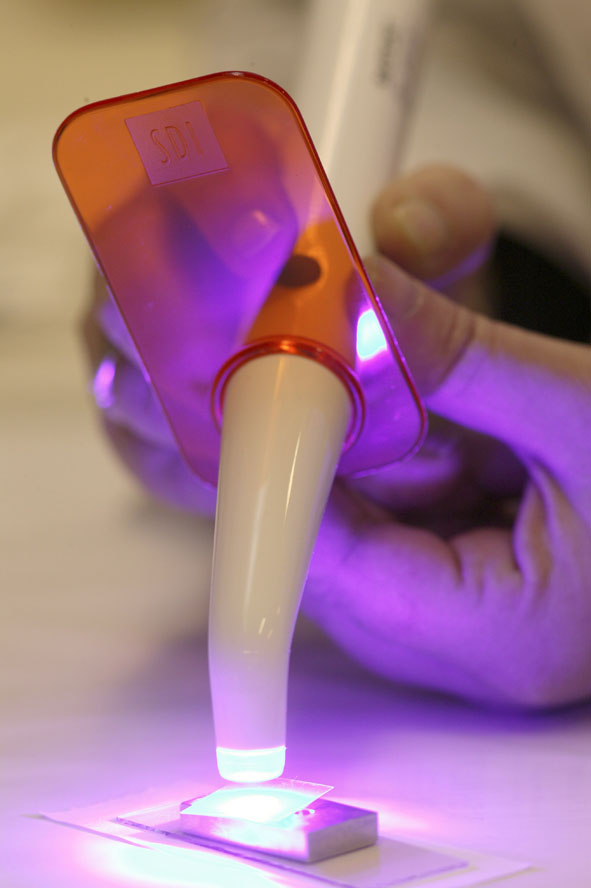

Dental curing light

View on Wikipedia

A dental curing light is a piece of dental equipment that is used for polymerization of light-cure resin-based composites.[1] It can be used on several different dental materials that are curable by light. The light used falls under the visible blue light spectrum. This light is delivered over a range of wavelengths and varies for each type of device. There are four basic types of dental curing light sources: tungsten halogen, light-emitting diodes (LED), plasma arcs, and lasers. The two most common are halogen and LEDs.

History

[edit]In the early 1960s, the first light curing resin composites were developed.[2] This led to the development of the first curing light, called Nuva Light, by Dentsply/Caulk in the 1970s. Nuva Light used ultraviolet light to cure resin composites. It was discontinued due to this requirement, as well as the fact that the shorter wavelengths of UV light did not penetrate deeply enough into the resin to adequately cure it.[3]

During the early 1980s, advances in the area of visible-light curing led to the creation of a curing device using blue light. The next type of curing light developed was the quartz-halogen bulb;[4] this device had longer wavelengths of the visible light spectrum and allowed for greater penetration of the curing light and light energy for resin composites.[3] The halogen curing light replaced the UV curing light.

The 1990s presented great improvements in light curing devices. As dental restorative materials advanced, so too did the technology used to cure these materials; the focus was to improve the intensity in order to be able to cure faster and deeper. In 1998 the plasma arc curing light was introduced.[5] It uses a high intensity light source, a fluorescent bulb containing plasma, in order to cure the resin-based composite, and claimed to cure resin composite material within 3 seconds. In practice, however, while the plasma arc curing light proved to be popular, negative aspects (including, but not limited to, an expensive initial price, curing times longer than the claimed 3 seconds, and expensive maintenance) of these lights resulted in the development of other curing light technologies.

The latest advancement in technology is the LED curing light. While LED curing lights have been available since the 1990s, they were not widely used until the frustrations presented through ownership of plasma arc lights became unbearable. While the LED curing light is a huge step forward from the initial curing light offerings, refinements and new technologies are continually being developed with the goal of quicker and more thorough curing of resin composites.

Tungsten halogen

[edit]

The tungsten halogen curing light, also known as simply "halogen curing light" is the most frequent polymerization source used in dental offices.[6] In order for the light to be produced, an electric current flows through a thin tungsten filament, which functions as a resistor.[6] This resistor is then “heated to temperatures of about 3,000 Kelvin, it becomes incandescent and emits infrared and electromagnetic radiation in the form of visible light”.[6] It provides a blue light between 400 and 500 nm, with an intensity of 400–600 mW cm−2.[7] This type of curing light however has certain drawbacks, the first of which is the large amounts of heat that the filament generates. This requires that the curing light have a ventilating fan installed which results in a larger curing light.[6] The fan generates a sound that may disturb some patients, and the wattage of the bulb is such (e.g. 80 W) these curing lights must be plugged into a power source; that is, they are not cordless. Furthermore, this light requires frequent monitoring and replacement of the actual curing light bulb because of the high temperatures that are reached. (For example, one model uses a bulb with an estimated life of 50 hours which would require annual replacement, assuming 12 minutes' use per day, 250 days per year.) Also, the time needed to fully cure the material is much more than the LED curing light.

Light emitting diode

[edit]

These curing lights use one or more light-emitting diodes [LEDs] and produce blue light that cures the dental material. LEDs as light-curing sources were first suggested in the literature in 1995.[8] A short history of LED curing in dentistry was published in 2013.[9] This light uses a gallium nitride-based semiconductor for blue light emission.[6]

A 2004 article in the American Dental Association's journal explained, "In LED’s, a voltage is applied across the junctions of two doped semi- conductors (n-doped and p-doped), resulting in the generation and emission of light in a specific wavelength range. By controlling the chemical composition of the semiconductor combination, one can control the wavelength range. The dental LED curing lights use LED’s that produce a narrow spectrum of blue light in the 400–500 nm range (with a peak wavelength of about 460 nm), which is the useful energy range for activating the CPQ molecule most commonly used to initiate the photo-polymerization of dental monomers."[6]

These curing lights are very different from halogen curing lights. They are more lightweight, portable and effective. The heat generated from LED curing lights is much less which means it does not require a fan to cool it. Since the fan was no longer needed, a more lightweight and smaller light could be designed. The portability of it comes from the low consumption of power. The LED can now use rechargeable batteries, making it much more comfortable and easier to use.

The latest[when?] LED curing light cures material much faster than halogen lamps and previous LED curing lights. It uses a single high-intensity blue LED with a larger semiconductor crystal.[6] Light intensity and the illumination area has been increased with an output of 1,000 mW/cm2.[6] In order to emit such a high intensity light, it uses a highly reflective mirror film consisting of "multilayer polymer film technology".[6]

Operation

[edit]The halogen and LED curing lights work in the same way. Both of these lights require the operator to press a button or a trigger in order to turn on the blue light. A trigger is pressed to activate the halogen curing lights. Older models require the operator to hold down the trigger in order for the light to emit, whereas newer models only require the trigger to be pressed once. The light will remain on in both the newer models of halogen and LED lights until the timer expires after the trigger or button is pressed. When the light is turned on, it is placed directly over the tooth with the material until it is cured.

Significance

[edit]This section possibly contains original research. (February 2012) |

The development of the curing light greatly changed dentistry. Prior to the development of the dental curing light, different materials had to be used in order to have a resin based composite material placed in a tooth. The material used prior to this development was a self-curing resin material. These materials, an A material and a B material, were mixed separately before application. The A material was the base and the B material was the catalyst. This resin material was mixed first and then placed in the tooth. It is then hardened fully after 30–60 seconds. This presented several issues to the dentist. One issue was that the dentist did not have control over how quickly the material cured—once mixed the curing process started. This resulted in the dentist having to quickly and properly place the material in the tooth. If the material was not properly placed, then the material had to be excavated and the process started over again.

The development of this new technology gave way to new light activated resin materials. These new materials are very different from the previous ones. These materials do not need to be mixed and can be dispensed directly into the site. This new malleable resin material can only be fully cured with a dental curing light. This presents new advantages for dentists: the time constraint is now lifted and the dentist can now assure that the material is properly placed.

References

[edit]- ^ Sherwood, Anand (2010). Essentials of Operative Dentistry. St. Louis, MO: Jaypee Brothers Medical.

- ^ Strassler, Howard E. "The Physics of Light Curing and Its Clinical Implications Compendium of Continuing Education in Dentistry". AEGIS Communications. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Curing lights for Composite Resins". Health Mantra: Your Mantra for Health, Wealth and Prosperity!. Health mantra. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ^ "Curing Lights at a Glance". LED Technology Here to stay 2002:1–6. 3m ESPE. Retrieved 2 December 2011.

- ^ Mahn, Eduardo (February 2011). "Light PolyMerization". Inside Dentistry. 7 (2). AEGIS Communications.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Wiggins, KM; Hartung, M; Althoff, O; Wastian, C; Mitra, SB (2004). "Curing performance of a new-generation light-emitting diode dental curing unit". Journal of the American Dental Association. 135 (10): 1471–9. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2004.0059. PMID 15551990.

- ^ Wataha, JC; Lewis, JB; Lockwood, PE; Noda, M; Messer, RL; Hsu, S (2008). "Response of THP-1 monocytes to blue light from dental curing lights". Journal of Oral Rehabilitation. 35 (2): 105–10. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2842.2007.01806.x. PMID 18197843.

- ^ Mills, R. W. (1995). "Blue light emitting diodes--another method of light curing?". British Dental Journal. 178 (5): 169. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.4808693. PMID 7702950.

- ^ Jandt, KD; Mills, RW (2013). "A brief history of LED photopolymerization". Dental Materials. 29 (6): 605–617. doi:10.1016/j.dental.2013.02.003. PMID 23507002.