Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Retina

View on Wikipedia

| Retina | |

|---|---|

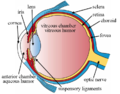

Right human eye cross-sectional view; eyes vary significantly among animals. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | UK: /ˈrɛtɪnə/, US: /ˈrɛtənə/, pl. retinae /-ni/ |

| Part of | Eye |

| System | Visual system |

| Artery | Central retinal artery |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | rēte, tunica interna bulbi |

| MeSH | D012160 |

| TA98 | A15.2.04.002 |

| TA2 | 6776 |

| FMA | 58301 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The retina (from Latin rete 'net'; pl. retinae or retinas) is the innermost, light-sensitive layer of tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focused two-dimensional image of the visual world on the retina, which then processes that image within the retina and sends nerve impulses along the optic nerve to the visual cortex to create visual perception. The retina serves a function which is in many ways analogous to that of the film or image sensor in a camera.

The neural retina consists of several layers of neurons interconnected by synapses and is supported by an outer layer of pigmented epithelial cells. The primary light-sensing cells in the retina are the photoreceptor cells, which are of two types: rods and cones. Rods function mainly in dim light and provide monochromatic vision. Cones function in well-lit conditions and are responsible for the perception of colour through the use of a range of opsins, as well as high-acuity vision used for tasks such as reading. A third type of light-sensing cell, the photosensitive ganglion cell, is important for entrainment of circadian rhythms and reflexive responses such as the pupillary light reflex.

Light striking the retina initiates a cascade of chemical and electrical events that ultimately trigger nerve impulses that are sent to various visual centres of the brain through the fibres of the optic nerve. Neural signals from the rods and cones undergo processing by other neurons, whose output takes the form of action potentials in retinal ganglion cells whose axons form the optic nerve.[1]

In vertebrate embryonic development, the retina and the optic nerve originate as outgrowths of the developing brain, specifically the embryonic diencephalon; thus, the retina is considered part of the central nervous system (CNS) and is actually brain tissue.[2][3] It is the only part of the CNS that can be visualized noninvasively. Like most of the brain, the retina is isolated from the vascular system by the blood–brain barrier. The retina is the part of the body with the greatest continuous energy demand.[4]

Structure

[edit]Inverted versus non-inverted retina

[edit]The vertebrate retina is inverted in the sense that the light-sensing cells are in the back of the retina, so that light has to pass through layers of neurons and capillaries before it reaches the photosensitive sections of the rods and cones.[5] The ganglion cells, whose axons form the optic nerve, are at the front of the retina; therefore, the optic nerve must cross through the retina en route to the brain. No photoreceptors are in this region, giving rise to the blind spot.[6] In contrast, in the cephalopod retina, the photoreceptors are in front, with processing neurons and capillaries behind them. Because of this, cephalopods do not have a blind spot.

Although the overlying neural tissue is partly transparent, and the accompanying glial cells have been shown to act as fibre-optic channels to transport photons directly to the photoreceptors,[7][8] light scattering does occur.[9] Some vertebrates, including humans, have an area of the central retina adapted for high-acuity vision. This area, termed the fovea centralis, is avascular (does not have blood vessels), and has minimal neural tissue in front of the photoreceptors, thereby minimizing light scattering.[9]

The cephalopods have a non-inverted retina, which is comparable in resolving power to the eyes of many vertebrates. Squid eyes do not have an analog of the vertebrate retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Although their photoreceptors contain a protein, retinochrome, that recycles retinal and replicates one of the functions of the vertebrate RPE, cephalopod photoreceptors are likely not maintained as well as in vertebrates, and that as a result, the useful lifetime of photoreceptors in invertebrates is much shorter than in vertebrates.[10] Having easily replaced stalk eyes (some lobsters) or retinae (some spiders, such as Deinopis[11]) rarely occurs.

The cephalopod retina does not originate as an outgrowth of the brain, as the vertebrate one does. This difference suggests that vertebrate and cephalopod eyes are not homologous, but have evolved separately. From an evolutionary perspective, a more complex structure such as the inverted retina can generally come about as a consequence of two alternate processes - an advantageous "good" compromise between competing functional limitations, or as a historical maladaptive relic of the convoluted path of organ evolution and transformation. Vision is an important adaptation in higher vertebrates.

A third view of the "inverted" vertebrate eye is that it combines two benefits - the maintenance of the photoreceptors mentioned above, and the reduction in light intensity necessary to avoid blinding the photoreceptors, which are based on the extremely sensitive eyes of the ancestors of modern hagfish (fish that live in very deep, dark water).[12]

A recent study on the evolutionary purpose for the inverted retina structure from the APS (American Physical Society)[13] says that "The directional of glial cells helps increase the clarity of human vision. But we also noticed something rather curious: the colours that best passed through the glial cells were green to red, which the eye needs most for daytime vision. The eye usually receives too much blue—and thus has fewer blue-sensitive cones.

Further computer simulations showed that green and red are concentrated five to ten times more by the glial cells, and into their respective cones, than blue light. Instead, excess blue light gets scattered to the surrounding rods. This optimization is such that color vision during the day is enhanced, while night-time vision suffers very little".

Retinal layers

[edit]

The vertebrate retina has 10 distinct layers.[15] From closest to farthest from the vitreous body:

- Inner limiting membrane – basement membrane elaborated by Müller cells

- Nerve fiber layer – axons of the ganglion cell bodies (a thin layer of Müller cell footplates exists between this layer and the inner limiting membrane)

- Ganglion cell layer – contains nuclei of ganglion cells, the axons of which become the optic nerve fibres, and some displaced amacrine cells[2]

- Inner plexiform layer – contains the synapse between the bipolar cell axons and the dendrites of the ganglion and amacrine cells[2]

- Inner nuclear layer – contains the nuclei and surrounding cell bodies (perikarya) of the amacrine cells, bipolar cells, and horizontal cells[2]

- Outer plexiform layer – projections of rods and cones ending in the rod spherule and cone pedicle, respectively, these make synapses with dendrites of bipolar cells and horizontal cells.[2] In the macular region, this is known as the fiber layer of Henle.

- Outer nuclear layer – cell bodies of rods and cones

- External limiting membrane – layer that separates the inner segment portions of the photoreceptors from their cell nuclei

- Inner segment / outer segment layer – inner segments and outer segments of rods and cones, the outer segments contain a highly specialized light-sensing apparatus.[16][17]

- Retinal pigment epithelium – single layer of cuboidal epithelial cells (with extrusions not shown in diagram). This layer is closest to the choroid, and provides nourishment and supportive functions to the neural retina, The black pigment melanin in the pigment layer prevents light reflection throughout the globe of the eyeball; this is extremely important for clear vision.[18][19][20]

These layers can be grouped into four main processing stages—photoreception; transmission to bipolar cells; transmission to ganglion cells, which also contain photoreceptors, the photosensitive ganglion cells; and transmission along the optic nerve. At each synaptic stage, horizontal and amacrine cells also are laterally connected.

The optic nerve is a central tract of many axons of ganglion cells connecting primarily to the lateral geniculate body, a visual relay station in the diencephalon (the rear of the forebrain). It also projects to the superior colliculus, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, and the nucleus of the optic tract. It passes through the other layers, creating the optic disc in primates.[21]

Additional structures, not directly associated with vision, are found as outgrowths of the retina in some vertebrate groups. In birds, the pecten is a vascular structure of complex shape that projects from the retina into the vitreous humour; it supplies oxygen and nutrients to the eye, and may also aid in vision. Reptiles have a similar, but much simpler, structure.[22]

In adult humans, the entire retina is about 72% of a sphere about 22 mm in diameter. The entire retina contains about 7 million cones and 75 to 150 million rods. The optic disc, a part of the retina sometimes called "the blind spot" because it lacks photoreceptors, is located at the optic papilla, where the optic-nerve fibres leave the eye. It appears as an oval white area of 3 mm2. Temporal (in the direction of the temples) to this disc is the macula, at whose centre is the fovea, a pit that is responsible for sharp central vision, but is actually less sensitive to light because of its lack of rods. Human and non-human primates possess one fovea, as opposed to certain bird species, such as hawks, that are bifoviate, and dogs and cats, that possess no fovea, but a central band known as the visual streak.[citation needed] Around the fovea extends the central retina for about 6 mm and then the peripheral retina. The farthest edge of the retina is defined by the ora serrata. The distance from one ora to the other (or macula), the most sensitive area along the horizontal meridian, is about 32 mm.[clarification needed]

In section, the retina is no more than 0.5 mm thick. It has three layers of nerve cells and two of synapses, including the unique ribbon synapse. The optic nerve carries the ganglion-cell axons to the brain, and the blood vessels that supply the retina. The ganglion cells lie innermost in the eye while the photoreceptive cells lie beyond. Because of this counter-intuitive arrangement, light must first pass through and around the ganglion cells and through the thickness of the retina, (including its capillary vessels, not shown) before reaching the rods and cones. Light is absorbed by the retinal pigment epithelium or the choroid (both of which are opaque).

The white blood cells in the capillaries in front of the photoreceptors can be perceived as tiny bright moving dots when looking into blue light. This is known as the blue field entoptic phenomenon (or Scheerer's phenomenon).

Between the ganglion-cell layer and the rods and cones are two layers of neuropils, where synaptic contacts are made. The neuropil layers are the outer plexiform layer and the inner plexiform layer. In the outer neuropil layer, the rods and cones connect to the vertically running bipolar cells, and the horizontally oriented horizontal cells connect to ganglion cells.

The central retina predominantly contains cones, while the peripheral retina predominantly contains rods. In total, the retina has about seven million cones and a hundred million rods. At the centre of the macula is the foveal pit where the cones are narrow and long, and arranged in a hexagonal mosaic, the most dense, in contradistinction to the much fatter cones located more peripherally in the retina.[23] At the foveal pit, the other retinal layers are displaced, before building up along the foveal slope until the rim of the fovea, or parafovea, is reached, which is the thickest portion of the retina. The macula has a yellow pigmentation, from screening pigments, and is known as the macula lutea. The area directly surrounding the fovea has the highest density of rods converging on single bipolar cells. Since its cones have a much lesser convergence of signals, the fovea allows for the sharpest vision the eye can attain.[2]

Though the rod and cones are a mosaic of sorts, transmission from receptors, to bipolars, to ganglion cells is not direct. Since about 150 million receptors and only 1 million optic nerve fibres exist, convergence and thus mixing of signals must occur. Moreover, the horizontal action of the horizontal and amacrine cells can allow one area of the retina to control another (e.g. one stimulus inhibiting another). This inhibition is key to lessening the sum of messages sent to the higher regions of the brain. In some lower vertebrates (e.g. the pigeon), control of messages is "centrifugal" – that is, one layer can control another, or higher regions of the brain can drive the retinal nerve cells, but in primates, this does not occur.[2]

Layers imagable with optical coherence tomography

[edit]Using optical coherence tomography (OCT), at least 13 layers can be identified in the retina. The layers and anatomical correlation are:[24][25][26]

From innermost to outermost, the layers identifiable by OCT are as follows:

| # | OCT Layer / Conventional Label | Anatomical Correlate | Reflectivity | Specific

anatomical boundaries? |

Additional

references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Posterior cortical vitreous | Posterior cortical vitreous | Hyper-reflective | Yes | [25] |

| 2 | Preretinal space | In eyes where the vitreous has fully or partially detached from the retina, this is the space created between the posterior cortical vitreous face and the internal limiting membrane of the retina. | Hypo-reflective | [25] | |

| 3 | Internal limiting membrane (ILM) | Formed by Müller cell endfeet

(unclear if it can be observed on OCT) |

Hyper-reflective | No | [25] |

| Nerve fiber layer (NFL) | Ganglion cell axons travelling towards the optic nerve | ||||

| 4 | Ganglion cell layer (GCL) | Ganglion cell bodies (and some displaced amacrine cells) | Hypo-reflective | [25] | |

| 5 | Inner plexiform layer (IPL) | Synapses between bipolar, amacrine and ganglion cells | Hyper-reflective | [25] | |

| 6 | Inner nuclear layer (INL) | a) Horizontal, bipolar and amacrine cell bodies

b) Müller cell nuclei |

Hypo-reflective | [25] | |

| 7 | Outer plexiform layer (OPL) | Synapses between photoreceptor, bipolar and horizontal cells | Hyper-reflective | [25] | |

| 8 | (Inner half) Henle's nerve fiber layer (HL) | Photoreceptor axons

(obliquely orientated fibres; not present in mid-peripheral or peripheral retina) |

Hypo-reflective | No | [25] |

| (Outer half) Outer nuclear layer (ONL) | The photoreceptor cell bodies | ||||

| 9 | External limiting membrane (ELM) | Made of zonulae adherens between Müller cells and photoreceptor inner segments | Hyper-reflective | [25] | |

| 10 | Myoid zone (MZ) | The innermost portion of the photoreceptor inner segment (IS) containing:

|

Hypo-reflective | No | [27][28] |

| 11 | Ellipsoid zone (EZ) | The outermost portion of the photoreceptor inner segment (IS) packed with mitochondria | Very Hyper-reflective | No | [24][29][27][25][30][31] |

| IS/OS junction or Photoreceptor integrity line (PIL) | The photoreceptor connecting cilia which bridge the inner and outer segments of the photoreceptor cells. | ||||

| 12 | Photoreceptor outer segments (OS) | The photoreceptor outer segments (OS) which contain disks filled with opsin, the molecule that absorbs photons. | Hypo-reflective | [32][25] | |

| 13 | Interdigitation zone (IZ) | Apices of the RPE cells which encase part of the cone OSs.

Poorly distinguishable from RPE. Previously: "cone outer segment tips line" (COST) |

Hyper-reflective | No | |

| 14 | RPE/Bruch's complex | RPE phagosome zone | Very Hyper-reflective | No | [24][25] |

| RPE melanosome zone | Hypo-reflective | ||||

| RPE mitochondria zone + Junction between the RPE & Bruch's membrane | Very Hyper-reflective | ||||

| 15 | Choriocapillaris | Thin layer of moderate reflectivity in inner choroid | No | [25] | |

| 16 | Sattler's layer | Thick layer of round or ovalshaped hyperreflective profiles, with hyporeflective cores in mid-choroid | [25] | ||

| 17 | Haller's layer | Thick layer of oval-shaped hyperreflective profiles, with hyporeflective cores in outer choroid | [25] | ||

| 18 | Choroidal-scleral juncture | Zone at the outer choroid with a marked change in texture, in which large circular or ovoid profiles abut a

homogenous region of variable reflectivity |

[25] | ||

Development

[edit]Retinal development begins with the establishment of the eye fields mediated by the SHH and SIX3 proteins, with subsequent development of the optic vesicles regulated by the PAX6 and LHX2 proteins.[33] The role of Pax6 in eye development was elegantly demonstrated by Walter Gehring and colleagues, who showed that ectopic expression of Pax6 can lead to eye formation on Drosophila antennae, wings, and legs.[34] The optic vesicle gives rise to three structures: the neural retina, the retinal pigmented epithelium, and the optic stalk. The neural retina contains the retinal progenitor cells (RPCs) that give rise to the seven cell types of the retina. Differentiation begins with the retinal ganglion cells and concludes with production of the Muller glia.[35] Although each cell type differentiates from the RPCs in a sequential order, there is considerable overlap in the timing of when individual cell types differentiate.[33] The cues that determine a RPC daughter cell fate are coded by multiple transcription factor families including the bHLH and homeodomain factors.[36][37]

In addition to guiding cell fate determination, cues exist in the retina to determine the dorsal-ventral (D-V) and nasal-temporal (N-T) axes. The D-V axis is established by a ventral to dorsal gradient of VAX2, whereas the N-T axis is coordinated by expression of the forkhead transcription factors FOXD1 and FOXG1. Additional gradients are formed within the retina.[37] This spatial distribution may aid in proper targeting of RGC axons that function to establish the retinotopic map.[33]

Blood supply

[edit]This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

The retina is stratified into distinct layers, each containing specific cell types or cellular compartments[38] that have metabolisms with different nutritional requirements.[39] To satisfy these requirements, the ophthalmic artery bifurcates and supplies the retina via two distinct vascular networks: the choroidal network, which supplies the choroid and the outer retina, and the retinal network, which supplies the retina's inner layer.[40]

Although the inverted retina of vertebrates appears counter-intuitive, it is necessary for the proper functioning of the retina. The photoreceptor layer must be embedded in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), which performs at least seven vital functions,[41] one of the most obvious being to supply oxygen and other necessary nutrients needed for the photoreceptors to function.

Energy requirements

[edit]The energy requirements of the retina are even greater than that of the brain.[4] This is due to the additional energy needed to continuously renew the photoreceptor outer segments, of which 10% are shed daily.[4] Energy demands are greatest during dark adaptation when its sensitivity is most enhanced.[42] The choroid supplies about 75% of these nutrients to the retina and the retinal vasculature only 25%.[5]

When light strikes 11-cis-retinal (in the disks in the rods and cones), 11-cis-retinal changes to all-trans-retinal which then triggers changes in the opsins. Now, the outer segments do not regenerate the retinal back into the cis- form once it has been changed by light. Instead the retinal is pumped out to the surrounding RPE where it is regenerated and transported back into the outer segments of the photoreceptors. This recycling function of the RPE protects the photoreceptors against photo-oxidative damage[43][44] and allows the photoreceptor cells to have decades-long useful lives.

In birds

[edit]The bird retina is devoid of blood vessels, perhaps to give unobscured passage of light for forming images, thus giving better resolution. It is, therefore, a considered view that the bird retina depends for nutrition and oxygen supply on a specialized organ, called the "pecten" or pecten oculi, located on the blind spot or optic disk. This organ is extremely rich in blood vessels and is thought to supply nutrition and oxygen to the bird retina by diffusion through the vitreous body. The pecten is highly rich in alkaline phosphatase activity and polarized cells in its bridge portion – both befitting its secretory role.[45] Pecten cells are packed with dark melanin granules, which have been theorized to keep this organ warm with the absorption of stray light falling on the pecten. This is considered to enhance metabolic rate of the pecten, thereby exporting more nutritive molecules to meet the stringent energy requirements of the retina during long periods of exposure to light.[46]

Biometric identification and diagnosis of disease

[edit]The bifurcations and other physical characteristics of the inner retinal vascular network are known to vary among individuals,[47] and these individual variances have been used for biometric identification and for early detection of the onset of disease. The mapping of vascular bifurcations is one of the basic steps in biometric identification.[48] Results of such analyses of retinal blood vessel structure can be evaluated against the ground truth data[49] of vascular bifurcations of retinal fundus images that are obtained from the DRIVE dataset.[50] In addition, the classes of vessels of the DRIVE dataset have also been identified,[51] and an automated method for accurate extraction of these bifurcations is also available.[52] Changes in retinal blood circulation are seen with aging[53] and exposure to air pollution,[54] and may indicate cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension and atherosclerosis.[55][56][57] Determining the equivalent width of arterioles and venules near the optic disc is also a widely used technique to identify cardiovascular risks.[58]

Function

[edit]The retina translates an optical image into neural impulses starting with the patterned excitation of the colour-sensitive pigments of its rods and cones, the retina's photoreceptor cells. The excitation is processed by the neural system and various parts of the brain working in parallel to form a representation of the external environment in the brain.[citation needed]

The cones respond to bright light and mediate high-resolution colour vision during daylight illumination (also called photopic vision). The rod responses are saturated at daylight levels and do not contribute to pattern vision. However, rods do respond to dim light and mediate lower-resolution, monochromatic vision under very low levels of illumination (called scotopic vision). The illumination in most office settings falls between these two levels and is called mesopic vision. At mesopic light levels, both the rods and cones are actively contributing pattern information. What contribution the rod information makes to pattern vision under these circumstances is unclear.

The response of cones to various wavelengths of light is called their spectral sensitivity. In normal human vision, the spectral sensitivity of a cone falls into one of three subtypes, often called blue, green, and red, but more accurately known as short, medium, and long wavelength-sensitive cone subtypes. It is a lack of one or more of the cone subtypes that causes individuals to have deficiencies in colour vision or various kinds of colour blindness. These individuals are not blind to objects of a particular colour, but are unable to distinguish between colours that can be distinguished by people with normal vision. Humans have this trichromatic vision, while most other mammals lack cones with red sensitive pigment and therefore have poorer dichromatic colour vision. However, some animals have four spectral subtypes, e.g. the trout adds an ultraviolet subgroup to short, medium, and long subtypes that are similar to humans. Some fish are sensitive to the polarization of light as well.

In the photoreceptors, exposure to light hyperpolarizes the membrane in a series of graded shifts. The outer cell segment contains a photopigment. Inside the cell the normal levels of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) keep the Na+ channel open, and thus in the resting state the cell is depolarised. The photon causes the retinal bound to the receptor protein to isomerise to trans-retinal. This causes the receptor to activate multiple G-proteins. This in turn causes the Ga-subunit of the protein to activate a phosphodiesterase (PDE6), which degrades cGMP, resulting in the closing of Na+ cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels (CNGs). Thus the cell is hyperpolarised. The amount of neurotransmitter released is reduced in bright light and increases as light levels fall. The actual photopigment is bleached away in bright light and only replaced as a chemical process, so in a transition from bright light to darkness the eye can take up to thirty minutes to reach full sensitivity.

When thus excited by light, the photoceptor sends a proportional response synaptically to bipolar cells which in turn signal the retinal ganglion cells. The photoreceptors are also cross-linked by horizontal cells and amacrine cells, which modify the synaptic signal before it reaches the ganglion cells, the neural signals being intermixed and combined. Of the retina's nerve cells, only the retinal ganglion cells and few amacrine cells create action potentials.

In the retinal ganglion cells there are two types of response, depending on the receptive field of the cell. The receptive fields of retinal ganglion cells comprise a central, approximately circular area, where light has one effect on the firing of the cell, and an annular surround, where light has the opposite effect. In ON cells, an increment in light intensity in the centre of the receptive field causes the firing rate to increase. In OFF cells, it makes it decrease. In a linear model, this response profile is well described by a difference of Gaussians and is the basis for edge detection algorithms. Beyond this simple difference, ganglion cells are also differentiated by chromatic sensitivity and the type of spatial summation. Cells showing linear spatial summation are termed X cells (also called parvocellular, P, or midget ganglion cells), and those showing non-linear summation are Y cells (also called magnocellular, M, or parasol retinal ganglion cells), although the correspondence between X and Y cells (in the cat retina) and P and M cells (in the primate retina) is not as simple as it once seemed.

In the transfer of visual signals to the brain, the visual pathway, the retina is vertically divided in two, a temporal (nearer to the temple) half and a nasal (nearer to the nose) half. The axons from the nasal half cross the brain at the optic chiasma to join with axons from the temporal half of the other eye before passing into the lateral geniculate body.

Although there are more than 130 million retinal receptors, there are only approximately 1.2 million fibres (axons) in the optic nerve. So, a large amount of pre-processing is performed within the retina. The fovea produces the most accurate information. Despite occupying about 0.01% of the visual field (less than 2° of visual angle), about 10% of axons in the optic nerve are devoted to the fovea. The resolution limit of the fovea has been determined to be around 10,000 points. The information capacity is estimated at 500,000 bits per second (for more information on bits, see information theory) without colour or around 600,000 bits per second including colour.[59]

Spatial encoding

[edit]

When the retina sends neural impulses representing an image to the brain, it spatially encodes (compresses) those impulses to fit the limited capacity of the optic nerve. Compression is necessary because there are 100 times more photoreceptor cells than ganglion cells. This is done by "decorrelation", which is carried out by the "centre–surround structures", which are implemented by the bipolar and ganglion cells.

There are two types of centre–surround structures in the retina – on-centres and off-centres. On-centres have a positively weighted centre and a negatively weighted surround. Off-centres are just the opposite. Positive weighting is more commonly known as excitatory, and negative weighting as inhibitory.

These centre–surround structures are not physical apparent, in the sense that one cannot see them by staining samples of tissue and examining the retina's anatomy. The centre–surround structures are logical (i.e., mathematically abstract) in the sense that they depend on the connection strengths between bipolar and ganglion cells. It is believed that the connection strength between cells is caused by the number and types of ion channels embedded in the synapses between the bipolar and ganglion cells.

The centre–surround structures are mathematically equivalent to the edge detection algorithms used by computer programmers to extract or enhance the edges in a digital photograph. Thus, the retina performs operations on the image-representing impulses to enhance the edges of objects within its visual field. For example, in a picture of a dog, a cat and a car, it is the edges of these objects that contain the most information. In order for higher functions in the brain (or in a computer for that matter) to extract and classify objects such as a dog and a cat, the retina is the first step to separating out the various objects within the scene.

As an example, the following matrix is at the heart of a computer algorithm that implements edge detection. This matrix is the computer equivalent to the centre–surround structure. In this example, each box (element) within this matrix would be connected to one photoreceptor. The photoreceptor in the centre is the current receptor being processed. The centre photoreceptor is multiplied by the +1 weight factor. The surrounding photoreceptors are the "nearest neighbors" to the centre and are multiplied by the −1/8 value. The sum of all nine of these elements is finally calculated. This summation is repeated for every photoreceptor in the image by shifting left to the end of a row and then down to the next line.

| -1/8 | -1/8 | -1/8 |

| -1/8 | +1 | -1/8 |

| -1/8 | -1/8 | -1/8 |

The total sum of this matrix is zero, if all the inputs from the nine photoreceptors are of the same value. The zero result indicates the image was uniform (non-changing) within this small patch. Negative or positive sums mean the image was varying (changing) within this small patch of nine photoreceptors.

The above matrix is only an approximation to what really happens inside the retina. The differences are:

- The above example is called "balanced". The term balanced means that the sum of the negative weights is equal to the sum of the positive weights so that they cancel out perfectly. Retinal ganglion cells are almost never perfectly balanced.

- The table is square while the centre–surround structures in the retina are circular.

- Neurons operate on spike trains traveling down nerve cell axons. Computers operate on a single floating-point number that is essentially constant from each input pixel. (The computer pixel is basically the equivalent of a biological photoreceptor.)

- The retina performs all these calculations in parallel while the computer operates on each pixel one at a time. The retina performs no repeated summations and shifting as would a computer.

- Finally, the horizontal and amacrine cells play a significant role in this process, but that is not represented here.

Here is an example of an input image and how edge detection would modify it.

Once the image is spatially encoded by the centre–surround structures, the signal is sent out along the optic nerve (via the axons of the ganglion cells) through the optic chiasm to the LGN (lateral geniculate nucleus). The exact function of the LGN is unknown at this time. The output of the LGN is then sent to the back of the brain. Specifically, the output of the LGN "radiates" out to the V1 primary visual cortex.

Simplified signal flow: Photoreceptors → Bipolar → Ganglion → Chiasm → LGN → V1 cortex

Clinical significance

[edit]There are many inherited and acquired diseases or disorders that may affect the retina. Some of them include:

- Retinitis pigmentosa is a group of genetic diseases that affect the retina and cause the loss of night vision and peripheral vision.

- Macular degeneration describes a group of diseases characterized by loss of central vision because of death or impairment of the cells in the macula.

- Cone-rod dystrophy (CORD) describes a number of diseases where vision loss is caused by deterioration of the cones and/or rods in the retina.

- In retinal separation, the retina detaches from the back of the eyeball. Ignipuncture is an outdated treatment method. The term retinal detachment is used to describe a separation of the neurosensory retina from the retinal pigment epithelium.[60] There are several modern treatment methods for fixing a retinal detachment: pneumatic retinopexy, scleral buckle, cryotherapy, laser photocoagulation and pars plana vitrectomy.

- Both hypertension and diabetes mellitus can cause damage to the tiny blood vessels that supply the retina, leading to hypertensive retinopathy and diabetic retinopathy.

- Retinoblastoma is a cancer of the retina.

- Retinal diseases in dogs include retinal dysplasia, progressive retinal atrophy, and sudden acquired retinal degeneration.

- Lipaemia retinalis is a white appearance of the retina, and can occur by lipid deposition in lipoprotein lipase deficiency.

- Retinal Detachment. The neural retina occasionally detaches from the pigment epithelium. In some instances, the cause of such detachment is injury to the eyeball that allows fluid or blood to collect between the neural retina and the pigment epithelium. Detachment is occasionally caused by contracture of fine collagenous fibrils in the vitreous humor, which pull areas of the retina toward the interior of the globe.[23]

- Night blindness: Night blindness occurs in any person with severe vitamin A deficiency. The reason for this is that without vitamin A, the amounts of retinal and rhodopsin that can be formed are severely depressed. This condition is called night blindness because the amount of light available at night is too little to permit adequate vision in vitamin A–deficient persons.[18]

In addition, the retina has been described as a "window" into the brain and body, given that abnormalities detected through an examination of the retina can discover both neurological and systemic diseases.[61]

Diagnosis

[edit]A number of different instruments are available for the diagnosis of diseases and disorders affecting the retina. Ophthalmoscopy and fundus photography have long been used to examine the retina. Recently, adaptive optics has been used to image individual rods and cones in the living human retina, and a company based in Scotland has engineered technology that allows physicians to observe the complete retina without any discomfort to patients.[62]

The electroretinogram is used to non-invasively measure the retina's electrical activity, which is affected by certain diseases. A relatively new technology, now becoming widely available, is optical coherence tomography (OCT). This non-invasive technique allows one to obtain a 3D volumetric or high resolution cross-sectional tomogram of the fine structures of the retina, with histologic quality. Retinal vessel analysis is a non-invasive method to examine the small arteries and veins in the retina which allows to draw conclusions about the morphology and the function of small vessels elsewhere in the human body. It has been established as a predictor of cardiovascular disease[63] and seems to have, according to a study published in 2019, potential in the early detection of Alzheimer's disease.[64]

Treatment

[edit]Treatment depends upon the nature of the disease or disorder.

Common treatment modalities

[edit]The following are commonly modalities of management for retinal disease:

- Intravitreal medication, such as anti-VEGF or corticosteroid agents

- Vitreoretinal surgery

- Use of nutritional supplements

- Modification of systemic risk factors for retinal disease

Uncommon treatment modalities

[edit]Retinal gene therapy

Gene therapy holds promise as a potential avenue to cure a wide range of retinal diseases. This involves using a non-infectious virus to shuttle a gene into a part of the retina. Recombinant adeno-associated virus (rAAV) vectors possess a number of features that render them ideally suited for retinal gene therapy, including a lack of pathogenicity, minimal immunogenicity, and the ability to transduce postmitotic cells in a stable and efficient manner.[65] rAAV vectors are increasingly utilized for their ability to mediate efficient transduction of retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), photoreceptor cells and retinal ganglion cells. Each cell type can be specifically targeted by choosing the appropriate combination of AAV serotype, promoter, and intraocular injection site.

Several clinical trials have already reported positive results using rAAV to treat Leber's congenital amaurosis, showing that the therapy was both safe and effective.[66][67] There were no serious adverse events, and patients in all three studies showed improvement in their visual function as measured by a number of methods. The methods used varied among the three trials, but included both functional methods such as visual acuity[67][68][69] and functional mobility[68][69][70] as well as objective measures that are less susceptible to bias, such as the pupil's ability to respond to light[66][71] and improvements on functional MRI.[72] Improvements were sustained over the long-term, with patients continuing to do well after more than 1.5 years.[66][67]

The unique architecture of the retina and its relatively immune-privileged environment help this process.[73] Tight junctions that form the blood retinal barrier separate the subretinal space from the blood supply, thus protecting it from microbes and most immune-mediated damage, and enhancing its potential to respond to vector-mediated therapies. The highly compartmentalized anatomy of the eye facilitates accurate delivery of therapeutic vector suspensions to specific tissues under direct visualization using microsurgical techniques.[74] In the sheltered environment of the retina, AAV vectors are able to maintain high levels of transgene expression in the retinal pigmented epithelium (RPE), photoreceptors, or ganglion cells for long periods of time after a single treatment. In addition, the eye and the visual system can be routinely and easily monitored for visual function and retinal structural changes after injections with noninvasive advanced technology, such as visual acuities, contrast sensitivity, fundus auto-fluorescence (FAF), dark-adapted visual thresholds, vascular diameters, pupillometry, electroretinography (ERG), multifocal ERG and optical coherence tomography (OCT).[75]

This strategy is effective against a number of retinal diseases that have been studied, including neovascular diseases that are features of age-related macular degeneration, diabetic retinopathy and retinopathy of prematurity. Since the regulation of vascularization in the mature retina involves a balance between endogenous positive growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and inhibitors of angiogenesis, such as pigment epithelium-derived factor (PEDF), rAAV-mediated expression of PEDF, angiostatin, and the soluble VEGF receptor sFlt-1, which are all antiangiogenic proteins, have been shown to reduce aberrant vessel formation in animal models.[76] Since specific gene therapies cannot readily be used to treat a significant fraction of patients with retinal dystrophy, there is a major interest in developing a more generally applicable survival factor therapy. Neurotrophic factors have the ability to modulate neuronal growth during development to maintain existing cells and to allow recovery of injured neuronal populations in the eye. AAV encoding neurotrophic factors such as fibroblast growth factor (FGF) family members and GDNF either protected photoreceptors from apoptosis or slowed down cell death.[76]

Organ transplantation Transplantation of retinae has been attempted, but without much success. At MIT, The University of Southern California, RWTH Aachen University, and the University of New South Wales, an "artificial retina" is under development: an implant which will bypass the photoreceptors of the retina and stimulate the attached nerve cells directly, with signals from a digital camera.

History

[edit]Around 300 BCE, Herophilos identified the retina from dissections of cadaver eyes. He called it the arachnoid layer, from its resemblance to a spider web, and retiform, from its resemblance to a casting net. The term arachnoid came to refer to a layer around the brain; the term retiform came to refer to the retina.[77]

Between 1011 and 1021 CE, Ibn Al-Haytham published numerous experiments demonstrating that sight occurs from light reflecting from objects into the eye. This is consistent with intromission theory and against emission theory, the theory that sight occurs from rays emitted by the eyes. However, Ibn Al-Haytham decided that the retina could not be responsible for the beginnings of vision because the image formed on it was inverted. Instead he decided it must begin at the surface of the lens.[78]

In 1604, Johannes Kepler worked out the optics of the eye and decided that the retina must be where sight begins. He left it up to other scientists to reconcile the inverted retinal image with our perception of the world as upright.[79]

In 1894, Santiago Ramón y Cajal published the first major characterization of retinal neurons in Retina der Wirbelthiere (The Retina of Vertebrates).[80]

George Wald, Haldan Keffer Hartline, and Ragnar Granit won the 1967 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their scientific research on the retina.[81]

A recent University of Pennsylvania study calculated that the approximate bandwidth of human retinae is 8.75 megabits per second, whereas a guinea pig's retinal transfer rate is 875 kilobits per second.[82]

MacLaren & Pearson and colleagues at University College London and Moorfields Eye Hospital in London, in 2006, showed that photoreceptor cells could be transplanted successfully in the mouse retina if donor cells were at a critical developmental stage.[83] Recently Ader and colleagues in Dublin showed, using the electron microscope, that transplanted photoreceptors formed synaptic connections.[84]

In 2012, Sebastian Seung and his laboratory at MIT launched EyeWire, an online Citizen science game where players trace neurons in the retina.[85] The goals of the EyeWire project are to identify specific cell types within the known broad classes of retinal cells, and to map the connections between neurons in the retina, which will help to determine how vision works.[86][87]

Additional images

[edit]-

The structures of the eye labeled

-

Another view of the eye and the structures of the eye labeled

-

Illustration of image as 'seen' by the retina independent of optic nerve and striate cortex processing

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ J, Krause William (2005). Krause's Essential Human Histology for Medical Students. Boca Raton, FL: Universal Publishers. ISBN 978-1-58112-468-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Sensory Reception: Human Vision: Structure and function of the Human Eye" vol. 27, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1987

- ^ "Penn Researchers Calculate How Much the Eye Tells the Brain" (Press release). PENN Medicine. 26 July 2006. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ a b c Viegas, Filipe O.; Neuhauss, Stephan C. F. (2021). "A Metabolic Landscape for Maintaining Retina Integrity and Function". Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 14. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2021.656000. ISSN 1662-5099. PMC 8081888. PMID 33935647.

- ^ a b Kolb, Helga (1995). "Simple Anatomy of the Retina". Webvision. PMID 21413391. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ Kolb, Helga. "Photoreceptors". Webvision. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ Franze K, Grosche J, Skatchkov SN, Schinkinger S, Foja C, Schild D, Uckermann O, Travis K, Reichenbach A, Guck J (2007). "Muller cells are living optical fibers in the vertebrate retina". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (20): 8287–8292. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.8287F. doi:10.1073/pnas.0611180104. PMC 1895942. PMID 17485670.

- ^ Baker, Oliver (23 April 2010). "Focus: Eye Cells as Light Pipes". Physical Review Focus. Vol. 25, no. 15. doi:10.1103/physrevfocus.25.15.

- ^ a b Bringmann A, Syrbe S, Görner K, Kacza J, Francke M, Wiedemann P, Reichenbach A (2018). "The primate fovea: Structure, function and development". Prog Retin Eye Res. 66: 49–84. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2018.03.006. PMID 29609042. S2CID 5045660.

- ^ Sperling, L.; Hubbard, R. (1 February 1975). "Squid retinochrome". The Journal of General Physiology. 65 (2): 235–251. doi:10.1085/jgp.65.2.235. ISSN 0022-1295. PMC 2214869. PMID 235007.

- ^ "How spiders see the world". Australian Museum. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ Drazen, J. C.; Yeh, J.; Friedman, J.; Condon, N. (June 2011). "Metabolism and enzyme activities of hagfish from shallow and deep water of the Pacific Ocean". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 159 (2): 182–187. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2011.02.018. PMID 21356325.

- ^ Labin, A. M.; Ribak, E. N. (16 April 2010). "Retinal Glial Cells Enhance Human Vision Acuity". Physical Review Letters. 104 (15) 158102. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.104o8102L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.158102. PMID 20482021.

- ^ Foundations of Vision Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Brian A. Wandell

- ^ "The Retinal Tunic". Virginia–Maryland Regional College of Veterinary Medicine. Archived from the original on 18 May 2007.

- ^ Goldberg AF, Moritz OL, Williams DS (2016). "Molecular basis for photoreceptor outer segment architecture". Prog Retin Eye Res. 55: 52–81. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2016.05.003. PMC 5112118. PMID 27260426.

- ^ Arshavsky VY, Burns ME (2012). "Photoreceptor signaling: supporting vision across a wide range of light intensities". J Biol Chem. 287 (3): 1620–1626. doi:10.1074/jbc.R111.305243. PMC 3265842. PMID 22074925.

- ^ a b Guyton and Hall Physiology. p. 612.

- ^ Sparrow JR, Hicks D, Hamel CP (2010). "The retinal pigment epithelium in health and disease". Curr Mol Med. 10 (9): 802–823. doi:10.2174/156652410793937813. PMC 4120883. PMID 21091424.

- ^ Letelier J, Bovolenta P, Martínez-Morales JR (2017). "The pigmented epithelium, a bright partner against photoreceptor degeneration". J Neurogenet. 31 (4): 203–215. doi:10.1080/01677063.2017.1395876. PMID 29113536. S2CID 1351539.

- ^ Shepherd, Gordon (2004). The Synaptic Organization of the Brain. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 217–225. ISBN 978-0-19-515956-1.

- ^ Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 465. ISBN 978-0-03-910284-5.

- ^ a b Guyton and Hall Physiology. p. 609.

- ^ a b c Cuenca, Nicolás; Ortuño-Lizarán, Isabel; Pinilla, Isabel (March 2018). "Cellular Characterization of OCT and Outer Retinal Bands Using Specific Immunohistochemistry Markers and Clinical Implications" (PDF). Ophthalmology. 125 (3): 407–422. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.09.016. hdl:10045/74474. PMID 29037595.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Staurenghi, Giovanni; Sadda, Srinivas; Chakravarthy, Usha; Spaide, Richard F. (2014). "Proposed Lexicon for Anatomic Landmarks in Normal Posterior Segment Spectral-Domain Optical Coherence Tomography". Ophthalmology. 121 (8): 1572–1578. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.02.023. PMID 24755005.

- ^ Meyer, Carsten H.; Saxena, Sandeep; Sadda, Srinivas R. (2017). Spectral domain optical coherence tomography in macular diseases. New Delhi: Springer. ISBN 978-81-322-3610-8. OCLC 964379175.

- ^ a b Hildebrand, Göran Darius; Fielder, Alistair R. (2011). "Anatomy and Physiology of the Retina". Pediatric Retina. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. pp. 39–65. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-12041-1_2. ISBN 978-3-642-12040-4.

- ^ Turgut, Burak; University, Fırat; Medicine, School of; Ophthalmology, Department of; Elazig; Turkey (2017). "Past and Present Terminology for the Retinal and Choroidal Structures in Optical Coherence Tomography". European Ophthalmic Review. 11 (1): 59. doi:10.17925/eor.2017.11.01.59.

- ^ "Outer Retinal Layers as Predictors of Vision Loss". Review of Ophthalmology.

- ^ Sherman, Jerome; Epshtein, Daniel (15 September 2012). "The ABCs of OCT". Review of Optometry.

- ^ Sherman, J (June 2009). "Photoreceptor integrity line joins the nerve fiber layer as key to clinical diagnosis". Optometry. 80 (6): 277–278. doi:10.1016/j.optm.2008.12.006. PMID 19465337.

- ^ Boston, Marco A. Bonini Filho, MD, and Andre J. Witkin, MD. "Outer Retinal Layers as Predictors of Vision Loss". Retrieved 7 April 2018.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Heavner, W; Pevny, L (1 December 2012). "Eye development and retinogenesis". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 4 (12) a008391. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a008391. PMC 3504437. PMID 23071378.

- ^ Halder, G; Callaerts, P; Gehring, WJ (24 March 1995). "Induction of ectopic eyes by targeted expression of the eyeless gene in Drosophila". Science. 267 (5205): 1788–1792. Bibcode:1995Sci...267.1788H. doi:10.1126/science.7892602. PMID 7892602.

- ^ Cepko, Connie (September 2014). "Intrinsically different retinal progenitor cells produce specific types of progeny". Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 15 (9): 615–627. doi:10.1038/nrn3767. ISSN 1471-003X. PMID 25096185. S2CID 15038502.

- ^ Hatakeyama, J; Kageyama, R (February 2004). "Retinal cell fate determination and bHLH factors". Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 15 (1): 83–89. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.09.005. PMID 15036211.

- ^ a b Lo Giudice, Quentin; Leleu, Marion; La Manno, Gioele; Fabre, Pierre J. (1 September 2019). "Single-cell transcriptional logic of cell-fate specification and axon guidance in early-born retinal neurons". Development. 146 (17): dev178103. doi:10.1242/dev.178103. ISSN 0950-1991. PMID 31399471.

- ^ Remington, Lee Ann (2012). Clinical anatomy and physiology of the visual system (3rd ed.). St. Louis: Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 978-1-4377-1926-0. OCLC 745905738.

- ^ Yu, DY; Yu, PK; Cringle, SJ; Kang, MH; Su, EN (May 2014). "Functional and morphological characteristics of the retinal and choroidal vasculature". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 40: 53–93. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2014.02.001. PMID 24583621. S2CID 21312546.

- ^ Kiel, Jeffrey W. Anatomy. Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- ^ Strauss, Olaf. "The retinal pigment epithelium". Webvision. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ Kaynezhad, Pardis; Tachtsidis, Ilias; Sivaprasad, Sobha; Jeffery, Glen (2023). "Watching the human retina breath in real time and the slowing of mitochondrial respiration with age". Scientific Reports. 13 (1): 6445. Bibcode:2023NatSR..13.6445K. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-32897-7. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 10119193. PMID 37081065.

- ^ "LIGHT-INDUCED DAMAGE to the RETINA". photobiology.info. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Diagrammatic representation of disc shedding and phagosome retrieval into the pigment epithelial cell". Archived from the original on 21 September 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ Bawa S.R.; YashRoy R.C. (1972). "Effect of dark and light adaptation on the retina and pecten of chicken". Experimental Eye Research. 13 (1): 92–97. doi:10.1016/0014-4835(72)90129-7. PMID 5060117. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014.

- ^ Bawa, S.R.; YashRoy, R.C. (1974). "Structure and function of vulture pecten". Cells Tissues Organs. 89 (3): 473–480. doi:10.1159/000144308. PMID 4428954. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015.

- ^ Sherman, T (1981). "On connecting large vessels to small – the meaning of murray law". Journal of General Physiology. 78 (4): 431–453. doi:10.1085/jgp.78.4.431. PMC 2228620. PMID 7288393.

- ^ Azzopardi G.; Petkov N. (2011). "Detection of Retinal Vascular Bifurcations by Trainable V4-Like Filters". Computer Analysis of Images and Patterns (PDF). Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Vol. 6854. pp. 451–459. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-23672-3_55. ISBN 978-3-642-23671-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Retinal fundus images – Ground truth of vascular bifurcations and crossovers". University of Groningen. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ "DRIVE: Digital Retinal Images for Vessel Extraction". Image Sciences Institute, Utrecht University. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- ^ Qureshi, T. A.; Habib, M.; Hunter, A.; Al-Diri, B. (June 2013). "A manually-labeled, artery/Vein classified benchmark for the DRIVE dataset". Proceedings of the 26th IEEE International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems. pp. 485–488. doi:10.1109/cbms.2013.6627847. ISBN 978-1-4799-1053-3. S2CID 7705121.

- ^ Qureshi, T. A.; Hunter, A.; Al-Diri, B. (June 2014). "A Bayesian Framework for the Local Configuration of Retinal Junctions". 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition. pp. 3105–3110. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1026.949. doi:10.1109/cvpr.2014.397. ISBN 978-1-4799-5118-5. S2CID 14654500.

- ^ Adar SD, Klein R, Klein BE, Szpiro AA, Cotch MF, Wong TY, et al. (2010). "Air Pollution and the microvasculature: a crosssectional assessment of in vivo retinal images in the population based multiethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA)". PLOS Med. 7 (11) e1000372. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000372. PMC 2994677. PMID 21152417.

- ^ Louwies, Tijs; Panis, Luc Int; Kicinski, Michal; Boever, Patrick De; Nawrot, Tim S. (2013). "Retinal Microvascular Responses to Short-Term Changes in Particulate Air Pollution in Healthy Adults". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (9): 1011–1016. Bibcode:2013EnvHP.121.1011L. doi:10.1289/ehp.1205721. PMC 3764070. PMID 23777785.

- ^ Tso, Mark O.M.; Jampol, Lee M. (1982). "Pathophysiology of Hypertensive Retinopathy". Ophthalmology. 89 (10): 1132–1145. doi:10.1016/s0161-6420(82)34663-1. PMID 7155524.

- ^ Chapman, N.; Dell'omo, G.; Sartini, M. S.; Witt, N.; Hughes, A.; Thom, S.; Pedrinelli, R. (1 August 2002). "Peripheral vascular disease is associated with abnormal arteriolar diameter relationships at bifurcations in the human retina". Clinical Science. 103 (2): 111–116. doi:10.1042/cs1030111. ISSN 0143-5221. PMID 12149100.

- ^ Patton, N.; Aslam, T.; MacGillivray, T.; Deary, I.; Dhillon, B.; Eikelboom, R.; Yogesan, K.; Constable, I. (2006). "Retinal image analysis: Concepts, applications and potential". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 25 (1): 99–127. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2005.07.001. PMID 16154379. S2CID 7434103.

- ^ Wong TY, Knudtson MD, Klein R, Klein BE, Meuer SM, Hubbard LD (2004). "Computer assisted measurement of retinal vessel diameters in the Beaver Dam Eye Study: methodology, correlation between eyes, and effect of refractive errors". Ophthalmology. 111 (6): 1183–1190. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2003.09.039. PMID 15177969.

- ^ Chen, Janglin; Cranton, Wayne; Fihn, Mark (2016). Handbook of visual display technology (2nd ed.). Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-14346-0. OCLC 962009228.

- ^ Retina (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Mosby. 2006. pp. 2013–2015. ISBN 978-0-323-02598-0. OCLC 62034580.

- ^ Frith, Peggy; Mehta, Arpan R (November 2021). "The retina as a window into the brain". The Lancet Neurology. 20 (11): 892. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(21)00332-X. PMC 7611980. PMID 34687632.

- ^ Seeing into the Future Archived 12 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine Ingenia, March 2007

- ^ Seidelmann, SB; et al. (1 November 2016). "Retinal Vessel Calibers in Predicting Long-Term Cardiovascular Outcomes". Circulation. 134 (18): 1328–1338. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023425. PMC 5219936. PMID 27682886.

- ^ Querques, G; et al. (11 January 2019). "Functional and morphological changes of the retinal vessels in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment". Scientific Reports. 9 (63): 63. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9...63Q. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-37271-6. PMC 6329813. PMID 30635610.

- ^ Dinculescu Astra; Glushakova Lyudmyla; Seok-Hong Min; Hauswirth William W (2005). "Adeno-associated virus-vectored gene therapy for retinal disease". Human Gene Therapy. 16 (6): 649–663. doi:10.1089/hum.2005.16.649. PMID 15960597.

- ^ a b c Cideciyan A. V.; Hauswirth W. W.; Aleman T. S.; Kaushal S.; Schwartz S. B.; Boye S. L.; Windsor E. A. M.; et al. (2009). "Human RPE65 gene therapy for Leber congenital amaurosis: persistence of early visual improvements and safety at 1 year". Human Gene Therapy. 20 (9): 999–1004. doi:10.1089/hum.2009.086. PMC 2829287. PMID 19583479.

- ^ a b c Simonelli F.; Maguire A. M.; Testa F.; Pierce E. A.; Mingozzi F.; Bennicelli J. L.; Rossi S.; et al. (2010). "Gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis is safe and effective through 1.5 years after vector administration". Molecular Therapy. 18 (3): 643–650. doi:10.1038/mt.2009.277. PMC 2839440. PMID 19953081.

- ^ a b Maguire A. M.; Simonelli F.; Pierce E. A.; Pugh E. N.; Mingozzi F.; Bennicelli J.; Banfi S.; et al. (2008). "Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber's congenital amaurosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (21): 2240–2248. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802315. PMC 2829748. PMID 18441370.

- ^ a b Maguire A. M.; High K. A.; Auricchio A.; Wright J. F.; Pierce E. A.; Testa F.; Mingozzi F.; et al. (2009). "Age-dependent effects of RPE65 gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial". Lancet. 374 (9701): 1597–1605. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61836-5. PMC 4492302. PMID 19854499.

- ^ Bainbridge J. W. B.; Smith A. J.; Barker S. S.; Robbie S.; Henderson R.; Balaggan K.; Viswanathan A.; et al. (2008). "Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber's congenital amaurosis" (PDF). The New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (21): 2231–2239. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.574.4003. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0802268. hdl:10261/271174. PMID 18441371. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 August 2017.

- ^ Hauswirth W. W.; Aleman T. S.; Kaushal S.; Cideciyan A. V.; Schwartz S. B.; Wang L.; Conlon T. J.; et al. (2008). "Treatment of Leber Congenital Amaurosis Due to RPE65Mutations by Ocular Subretinal Injection of Adeno-Associated Virus Gene Vector: Short-Term Results of a Phase I Trial". Human Gene Therapy. 19 (10): 979–990. doi:10.1089/hum.2008.107. PMC 2940541. PMID 18774912.

- ^ Ashtari M.; Cyckowski L. L.; Monroe J. F.; Marshall K. A.; Chung D. C.; Auricchio A.; Simonelli F.; et al. (2011). "The human visual cortex responds to gene therapy-mediated recovery of retinal function". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 121 (6): 2160–2168. doi:10.1172/JCI57377. PMC 3104779. PMID 21606598.

- ^ Bennett J (2003). "Immune response following intraocular delivery of recombinant viral vectors". Gene Therapy. 10 (11): 977–982. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3302030. PMID 12756418.

- ^ Curace Enrico M.; Auricchio Alberto (2008). "Versatility of AAV vectors for retinal gene transfer". Vision Research. 48 (3): 353–359. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2007.07.027. PMID 17923143. S2CID 9926758.

- ^ den Hollander, Anneke I.; Roepman, Ronald; Koenekoop, Robert K.; Cremers, Frans P.M. (2008). "Leber congenital amaurosis: Genes, proteins and disease mechanisms". Progress in Retinal and Eye Research. 27 (4): 391–419. doi:10.1016/j.preteyeres.2008.05.003. PMID 18632300. S2CID 30202286.

- ^ a b Rolling, F. (2004). "Recombinant AAV-mediated gene transfer to the retina: gene therapy perspectives". Gene Therapy. 11 (S1): S26 – S32. doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3302366. ISSN 0969-7128. PMID 15454954.

- ^ Dobson, J. F. (March 1925). "Herophilus of Alexandria". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine. 18 (Sect_Hist_Med): 19–32. doi:10.1177/003591572501801704. ISSN 0035-9157. PMC 2201994. PMID 19984605.

- ^ Sabra, A. I. (Ed.). (1011–1021/1989). The optics of Ibn Al-Haytham: Books I-III: On direct vision (A. I. Sabra, Trans.). The Warburg Institute.

- ^ Fishman, R. S. (1973). "Kepler's Discovery of the Retinal Image". Archives of Ophthalmology. 89 (1): 59–61. doi:10.1001/archopht.1973.01000040061014. PMID 4567856. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Santiago Ramón y Cajal – Biographical". www.nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 6 October 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ "Nobelprize.org". nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ Reilly, Michael. "Calculating the speed of sight". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 31 May 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ MacLaren, RE; Pearson, RA; MacNeil, A; et al. (November 2006). "Retinal repair by transplantation of photoreceptor precursors" (PDF). Nature. 444 (7116): 203–207. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..203M. doi:10.1038/nature05161. hdl:2027.42/62596. PMID 17093405. S2CID 4415311.

- ^ Bartsch, U.; Oriyakhel, W.; Kenna, P. F.; Linke, S.; Richard, G.; Petrowitz, B.; Humphries, P.; Farrar, G. J.; Ader, M. (2008). "Retinal cells integrate into the outer nuclear layer and differentiate into mature photoreceptors after subretinal transplantation into adult mice". Experimental Eye Research. 86 (4): 691–700. doi:10.1016/j.exer.2008.01.018. PMID 18329018.

- ^ "About: EyeWire". Archived from the original on 13 February 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- ^ "Retina << EyeWire". Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ "EyeWire". Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- S. Ramón y Cajal, Histologie du Système Nerveux de l'Homme et des Vertébrés, Maloine, Paris, 1911.

- Rodieck RW (1965). "Quantitative analysis of cat retinal ganglion cell response to visual stimuli". Vision Res. 5 (11): 583–601. doi:10.1016/0042-6989(65)90033-7. PMID 5862581.

- Wandell, Brian A. (1995). Foundations of vision. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates. ISBN 978-0-87893-853-7.

- Wässle H, Boycott BB (1991). "Functional architecture of the mammalian retina". Physiol. Rev. 71 (2): 447–480. doi:10.1152/physrev.1991.71.2.447. PMID 2006220.

- Schulz HL, Goetz T, Kaschkoetoe J, Weber BH (2004). "The Retinome – Defining a reference transcriptome of the adult mammalian retina/retinal pigment epithelium". BMC Genomics (about a transcriptome for eye colour). 5 (1): 50. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-5-50. PMC 512282. PMID 15283859.

- Dowling, John (2007). "Retina". Scholarpedia. 2 (12): 3487. Bibcode:2007SchpJ...2.3487D. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.3487.

External links

[edit]- Histology of the Eye, edited by William Krause, Dept. Pathology and Anatomical science, University of Missouri School of Medicine

- Eye, Brain, and Vision – online book – by David Hubel

- Kolb, H., Fernandez, E., & Nelson, R. (2003). Webvision: The neural organization of the vertebrate retina. Salt Lake City, Utah: John Moran Eye Center, University of Utah. Retrieved 22 July 2014.

- Retinal layers image. NeuroScience 2nd Ed at United States National Library of Medicine

- Jeremy Nathans's Seminars: "The Vertebrate Retina: Structure, Function, and Evolution"

- Retina – Cell Centered Database

- Histology image: 07901loa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia: 002291

Retina

View on GrokipediaAnatomy

Macroscopic structure

The human retina forms a thin, circular to oval sheet that lines the posterior two-thirds of the eyeball, extending from the optic disc posteriorly to the ora serrata anteriorly. It has a diameter of approximately 30 to 40 mm and a surface area of about 1,100 mm², covering roughly 65-72% of the inner surface of the eye globe. The retina's thickness varies regionally, averaging 0.5 mm but thinning to about 0.1 mm at the fovea. This structure allows it to conform to the curved inner wall of the vitreous chamber, optimizing light capture across the visual field.[10][11] Regionally, the retina is divided into distinct zones with specialized functions. The optic disc, located nasally about 3-4 mm from the posterior pole, measures approximately 1.5-1.8 mm in diameter and serves as the exit point for retinal ganglion cell axons forming the optic nerve; this region lacks photoreceptors, creating the physiological blind spot. Centrally, the macula lutea, a 5-6 mm diameter yellowish area responsible for high-acuity vision, encompasses the fovea centralis—a 1.5 mm pit with the highest density of cone photoreceptors for detailed color vision. Surrounding these central structures is the peripheral retina, which extends to the ora serrata and predominates in rod photoreceptors for low-light and motion detection.[11][12][13] In vertebrates, including humans, the retina is inverted, meaning incoming light must pass through the inner neural layers before reaching the photoreceptor layer at the back, adjacent to the choroid. This contrasts with the non-inverted (everted) retina in cephalopods, where photoreceptors face directly toward the light source. Despite initial perceptions of inefficiency, the inverted design offers advantages such as space-saving for vascular and neural integration in compact eyes and reduced light scattering via specialized Müller glial cells, which act as fiber-optic-like waveguides to guide light efficiently to photoreceptors with minimal distortion or loss. The neurosensory retina adheres firmly to the underlying choroid through the retinal pigment epithelium, while anteriorly, it attaches to the vitreous humor via a firm adhesion at the vitreous base, which straddles the ora serrata—the serrated junction where the retina transitions to the ciliary body. This dual attachment maintains retinal stability, though disruptions can lead to detachment.[14][15][16]Microscopic layers

The retina is organized into ten microscopically distinct layers, extending from the inner surface adjacent to the vitreous humor to the outer surface bordering the choroid; this layered architecture facilitates the orderly processing of visual information through specialized cellular and synaptic arrangements. These layers are the internal limiting membrane, nerve fiber layer, ganglion cell layer, inner plexiform layer, inner nuclear layer, outer plexiform layer, outer nuclear layer, external limiting membrane, photoreceptor layer (comprising inner and outer segments of rods and cones), and retinal pigment epithelium. The internal limiting membrane serves as a thin basement membrane formed by the end feet of Müller glial cells, providing structural support. The nerve fiber layer consists of unmyelinated axons from retinal ganglion cells converging toward the optic disc. The ganglion cell layer contains the cell bodies of retinal ganglion cells, which integrate signals and project to the brain via the optic nerve. The inner plexiform layer is a synaptic zone rich in neuropil, where bipolar and amacrine cells connect with ganglion cells. The inner nuclear layer houses the nuclei of bipolar cells, horizontal cells, amacrine cells, and Müller glia. The outer plexiform layer features synapses between photoreceptors and second-order neurons. The outer nuclear layer includes the nuclei of rod and cone photoreceptors. The external limiting membrane is a fenestrated layer of adherens junctions between Müller cells and photoreceptors. The photoreceptor layer encompasses the inner segments (metabolic machinery) and outer segments (light-capturing discs) of rods and cones. The retinal pigment epithelium, the outermost layer, is a single layer of cuboidal cells essential for photoreceptor maintenance.[17] Key cell types populate these layers, enabling light detection and initial neural processing. Photoreceptors, located in the outer nuclear and photoreceptor layers, include rods (approximately 120 million per human retina), which mediate scotopic vision in low-light conditions with high sensitivity but no color discrimination, and cones (about 6 million), which support photopic vision and color perception under brighter illumination. Cones are categorized into three spectral types: L-cones (sensitive to long wavelengths, ~64% of total), M-cones (medium wavelengths, ~32%), and S-cones (short wavelengths, ~5%).[17][18] Bipolar cells, residing primarily in the inner nuclear layer, transmit signals vertically from photoreceptors to ganglion cells, with subtypes (ON and OFF) responding to light increments or decrements. Horizontal cells, also in the inner nuclear layer, extend processes into the outer plexiform layer for lateral inhibition, enhancing contrast. Amacrine cells, diverse in the inner nuclear and inner plexiform layers, provide inhibitory feedback and contribute to motion and direction selectivity through wide-ranging connections. Retinal ganglion cells, in the ganglion cell layer, output processed signals; prominent types include midget ganglion cells, which convey high-acuity, color-opponent information via small receptive fields, and parasol ganglion cells, which detect motion and luminance changes with larger fields.[17][19][20][21] Synaptic connections occur predominantly in the plexiform layers, integrating vertical signal relay with horizontal processing across the retinal network. In the outer plexiform layer, photoreceptor terminals (spherules for rods, pedicles for cones) synapse onto the dendrites of bipolar and horizontal cells, allowing direct vertical transmission from photoreceptors to bipolars while horizontal cells form lateral gap junctions and feedback synapses for surround inhibition and color opponency. The inner plexiform layer, stratified into sublaminae, hosts ribbon synapses from bipolar cells onto amacrine and ganglion cell dendrites, enabling complex computations such as temporal filtering and directional selectivity; for instance, amacrine cells provide recurrent inhibition to refine ganglion cell receptive fields. These interconnections ensure that raw photic input is transformed into feature-encoded signals before exiting via ganglion cell axons.[17][22] Optical coherence tomography (OCT) non-invasively images these layers by detecting tissue reflectivity, aiding in clinical correlation of histology with pathology; distinct bands arise from differences in cellular density, orientation, and composition. The nerve fiber layer, for example, appears hyperreflective due to the parallel alignment of ganglion cell axons, while the outer nuclear layer is hyporeflective owing to the loosely packed photoreceptor nuclei. The following table summarizes key anatomical-OCT correlations, including typical reflectivity patterns:| Anatomical Layer | OCT Band/Appearance | Reflectivity | Key Correlate/Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal limiting membrane + Nerve fiber layer | Vitreoretinal interface to NFL-IPL boundary | Hyperreflective | Basement membrane and bundled axons with high axial orientation. |

| Ganglion cell layer + Inner plexiform layer | GCL-IPL complex | Hypo- to hyperreflective (biphasic) | Cell bodies (hypo) and synaptic neuropil (hyper). |

| Inner nuclear layer | INL band | Hyporeflective | Nuclei and processes of second-order neurons. |

| Outer plexiform layer | OPL band | Hyperreflective | Synaptic densities and horizontal cell processes. |

| Outer nuclear layer | ONL band | Hyporeflective | Photoreceptor nuclei in low-density array. |

| External limiting membrane | ELM line | Hyperreflective | Adherens junctions at Müller-photoreceptor interface. |

| Photoreceptor inner/outer segments | Ellipsoid + Interdigitation zones | Hyper- (ellipsoid) to hypo- (outer segments) | Mitochondrial-rich inner segments; disc membranes in outer segments. |

| Retinal pigment epithelium + Bruch's membrane | RPE complex | Hyperreflective | Melanin granules and choriocapillaris backscattering. |