Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Doctor Sax

View on Wikipedia

Doctor Sax (Doctor Sax: Faust Part Three) is a novel by Jack Kerouac published in 1959. Kerouac wrote it in 1952 while living with William S. Burroughs in Mexico City.

Key Information

Composition

[edit]The novel was written quickly in the improvisatory style Kerouac called "spontaneous prose."[1] In a letter to Allen Ginsberg dated May 18, 1952, Kerouac wrote, "I'll simply blow [improvise like a jazz musician] on the vision of the Shadow in my 13th and 14th years on Sarah Ave. Lowell, culminated by the myth itself as I dreamt it in Fall 1948 . . . angles of my hoop-rolling boyhood as seen from the shroud."[2] In a letter to Ginsberg dated November 8 of the same year, Kerouac admits "Doctor Sax was written high on tea [marijuana] without pausing to think, sometimes Bill [Burroughs] would come in the room and so the chapter ended there..."[3]

Plot summary

[edit]The novel begins with Jackie Duluoz, based on Kerouac himself, relating a dream in which he finds himself in Lowell, Massachusetts, his childhood home town. Prompted by this dream, he recollects the story of his childhood of warm browns and sepia tones, along with his shrouded childhood fantasies, which have become inextricable from the memories.

The fantasies pertain to a castle in Lowell atop a muted green hill that Jackie calls Snake Hill. Underneath the misty grey castle, the Great World Snake sleeps. Various vampires, monsters, gnomes, werewolves, and dark magicians from all over the world gather to the mansion with the intention of awakening the Snake so that it will devour the entire world (although a small minority of them, derisively called "Dovists," believe that the Snake is merely "a husk of doves," and when it awakens it will burst open, releasing thousands of lace white doves. This myth is also present in a story told by Kerouac's character, Sal Paradise, in On the Road).

The eponymous Doctor Sax, also part of Jackie's fantasy world, is a dark but ultimately friendly figure with a shrouded black cape, an inky black slouch hat, a haunting laugh, and a "disease of the night" called Visagus Nightsoil that causes his skin to turn mossy green at night. Sax, who also came to Lowell because of the Great World Snake, lives in the forest in the neighboring town of Dracut, where he conducts various alchemical experiments, attempting to concoct a potion to destroy the Snake when it awakens.

When the Snake is finally awakened, Doctor Sax uses his potion on the Snake, but the potion fails to do any damage. Sax, defeated, discards his shadowy black costume and watches the events unfold as an ordinary man. As the Snake prepares to destroy the world, all seems lost until an enormous night colored bird, an ancient counterpart of the Snake, suddenly appears. Seizing the Snake in its beak, the bird flies upward into the heartbreakingly blue sky until it vanishes from view, leading the amazed Sax to muse, "I'll be damned, the universe disposes of its own evil!"

Character Key

[edit]Kerouac often based his fictional characters on friends and family.[4]

"Because of the objections of my early publishers I was not allowed to use the same personae names in each work."[5]

| Real-life person | Character name |

|---|---|

| Leo Kerouac | Emil "Pop" Duluoz |

| Gabrielle Kerouac | Ange |

| Gerard Kerouac | Gerard Duluoz |

| Caroline Kerouac | Catherine "Nin" Duluoz |

| George "G.J." Apostolos | Rigopoulos |

| Henry "Scotty" Beaulieu | Paul "Scotty" Boldieu |

| Freddie Bertrand | Vinny Bergerac |

| "Happy" Bertrand | Lucky Bergerac |

| Leona Bertrand | Charlie Bergerac |

| Billy Chandler | Dickie Hampshire |

| Duke Chiungos | Bruno Gringas |

| Omer X. Noel | Ali Zaza |

| Roland Salvas | Albert "Lousy" Lauzon |

Screenplay adaptation

[edit]

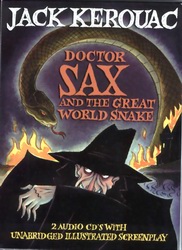

Kerouac also wrote a screenplay adaptation of the novel entitled Doctor Sax and the Great World Snake. It was never filmed, but in 1998, Kerouac's nephew Jim Sampas discovered the text in Kerouac's archives. He proceeded to produce the piece in audio form, much like a radio drama, and release it in 2003 from his independent record label, Gallery Six (named for the site of the famous Six Gallery reading), in a partnership with Mitch Winston's record label, Kid Lightning Enterprises. The release consisted of two CDs and a book containing the screenplay with illustrations by Richard Sala.

Voice acting

[edit]Narration: Robert Creeley

Jackie Duluoz, Voice, Count Condu, Boaz, Butcher, Man 1, Parakeet, Man 2 : Jim Carroll

Doctor Sax : Robert Hunter

Lousy: Ellis Paul

Vamp: Kate Pierson

The Wizard: Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Dicky: Bill Janovitz

Pa: Jim Eppard

Ma, Mother, Woman: Kristina Wacome

Gene: Jim Sampas

GJ: John Keegan

Blanche, Nin: Anne Emerick

Wizard's Wife, Woman 2: Maggie Estep

Score

[edit]In other media

[edit]The character Doctor Sax appeared in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen: Black Dossier by Alan Moore in a story written by Sal Paradise (from Kerouac's On the Road). He is mentioned as being the great-grandson of The Devil Doctor (because of the Doctor's creator, Sax Rohmer) and fights against Mina Murray, Allan Quatermain, Paradise and Dean Moriarty (who is the great-grandson of Manchu's rival and Sherlock Holmes' nemesis Professor Moriarty).

References

[edit]- ^ “The Essentials of Spontaneous Prose”

- ^ Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg: The Letters, ed. Bill Morgan and David Stanford (NY: Viking, 2010), p. 173.

- ^ ibid., p. 185.

- ^ Who’s Who: A Guide to Kerouac’s Characters

- ^ Kerouac, Jack. Visions of Cody. London and New York: Penguin Books Ltd. 1993.

- 1959. Doctor Sax, ISBN 0-8021-3049-6

- 2003. Doctor Sax and the Great World Snake, ISBN 0-9729733-0-3

External links

[edit]- Doctor Sax, read by Jack Kerouac with Sinatra playing in Background. For Louise Soerrels from the Allen Ginsberg papers, 1937-1994 at Stanford University.

Doctor Sax

View on GrokipediaPublication and Background

Publication History

Kerouac completed the manuscript for Doctor Sax in 1952 while living with William S. Burroughs in Mexico City.[7] The novel employs Kerouac's emerging spontaneous prose technique, drafted rapidly over several weeks amid the city's chaotic environment. Grove Press published Doctor Sax: Faust Part Three in 1959, marking it as the author's fifth novel following the breakthrough success of On the Road two years prior. The first edition appeared in two simultaneous states: a hardcover printing priced at $3.50 and a paperback Evergreen Black Cat edition (E-160) priced at $1.75. Despite Kerouac's rising fame, the book's nonlinear, dreamlike structure and experimental style limited its initial commercial distribution and reception compared to his more accessible road narratives.[8] Subsequent reprints omitted the "Faust Part Three" subtitle, simplifying the title to Doctor Sax to align with Kerouac's growing canon.[9] Key editions include a 1973 mass-market paperback from Ballantine Books (217 pages) and a 1994 Grove Press paperback reissue (245 pages, ISBN 9780802130495), which restored the original text without alterations.[9] In 2003, Gallery Six released a multimedia edition tying the novel to an audio adaptation, featuring unabridged recordings on two CDs with an illustrated screenplay, narrated by figures like Robert Creeley and Jim Carroll (144 pages, ISBN 9780972973304).[10] Later editions include the 2012 Penguin Classics paperback (ISBN 9780141198248) and a 2023 Grove Press reprint (ISBN 9780802162113, 256 pages).[9] These reprints sustained the work's availability, reflecting its enduring appeal among readers of Beat literature despite early modest sales.Context in Kerouac's Life and Work

Doctor Sax draws directly from Jack Kerouac's childhood in Lowell, Massachusetts, where he was born on March 12, 1922, to French-Canadian parents in a working-class neighborhood dominated by textile mills along the Merrimack River. The novel's setting and protagonist, Jackie Duluoz—Kerouac's recurring fictional stand-in—mirror his own early life amid immigrant communities, Catholic rituals, and the industrial landscape of the city, which shaped his sense of place and memory.[11][12] In Kerouac's expansive "Duluoz Legend," a semi-autobiographical cycle tracing the life of Jack Duluoz across multiple novels, Doctor Sax holds the second spot chronologically, depicting events from 1930 to 1936 during Duluoz's preadolescent years in Lowell, following Visions of Gerard (covering 1922–1926) and preceding The Town and the City (1935–1946) and Maggie Cassidy (1938–1939). Despite this early placement in the legend's timeline, the book was the fifth to be published, released by Grove Press in 1959.[12][13] The central figure of Doctor Sax emerged from a recurring dream Kerouac experienced in 1948, featuring a "shroudy stranger"—a mysterious, shadowy protector battling malevolent forces—which he revisited and developed into the novel's supernatural guardian while composing it in June 1952 at William S. Burroughs's home in Mexico City.[14] Kerouac wrote Doctor Sax amid his evolving literary style, bridging the structured realism of his first novel, The Town and the City (1950), with the improvisational "spontaneous prose" he refined in On the Road (1957); the book's 1959 publication came in the wake of On the Road's breakthrough success, marking Kerouac's rise as a Beat icon.[15][16] The work's mythic and fantastical dimensions reflect Kerouac's personal challenges, including the pervasive influence of his pious Catholic mother, Gabrielle-Ange Lévesque Kerouac, whose faith imbued his worldview with themes of sin, redemption, and the supernatural; the traumatic death of his father, Leo Kerouac, from stomach cancer in 1946; and his youthful immersion in be-bop jazz, which inspired the novel's rhythmic, improvisatory fantasy sequences evoking nocturnal adventures and hidden dangers.[12][17][11]Composition and Style

Writing Process

Kerouac composed the bulk of Doctor Sax during a stay with William S. Burroughs in Mexico City in the spring and summer of 1952, completing the manuscript in a three-week burst of intensive writing.[18] This period followed earlier sketches begun in 1948, drawing from his Lowell childhood memories as source material. The process exemplified his emerging spontaneous prose method, prioritizing uninterrupted flow over structured planning, with no outlining to constrain the narrative's blend of memoir and fantasy.[19] Kerouac's daily routine involved prolonged typing sessions fueled primarily by marijuana, which he smoked continuously to induce a hallucinatory state conducive to improvisation akin to jazz solos.[19] He often worked in isolated spots, such as Burroughs' bathroom, to minimize smoke exposure to his host while maintaining focus.[19] Burroughs contributed to the environment by supplying drugs, reflecting their shared experimental interests.[20] Post-draft revisions were minimal, aligning with Kerouac's belief that editing disrupted the raw authenticity of thought: "By not revising what you’ve already written you simply give the reader the actual workings of your mind."[19] The approximately 61,000-word manuscript was submitted to publishers soon after completion but faced repeated rejections owing to its unconventional, stream-of-consciousness style, delaying publication until 1959.[21][22]Influences and Techniques

Kerouac's Doctor Sax draws heavily on literary influences that infuse the novel with Faustian and gothic elements. The work is subtitled Faust Part Three, explicitly updating Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's Faust by reimagining the legend through a modern, autobiographical lens of good versus evil, where the protagonist confronts supernatural forces rooted in childhood imagination.[4] Shadowy figures in the narrative, such as the enigmatic Doctor Sax, echo the mysterious anti-heroes in H.P. Lovecraft's cosmic horror and Edgar Allan Poe's tales of the macabre, blending psychological dread with the uncanny.[23] Additionally, the novel incorporates New England gothic traditions from Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville, evident in its exploration of moral ambiguity, isolation, and the haunting interplay between the mundane and the mythic in a working-class mill town setting.[24] Cultural influences from 1940s bop jazz profoundly shaped the novel's rhythmic structure and improvisational flow. Kerouac modeled his prose on Charlie Parker's bebop solos, adopting long, flowing phrases with minimal punctuation to mimic the saxophonist's breath control and rhythmic complexity, as seen in transcriptions of Parker's improvisations like "Koko."[25] This influence extends to the associative, ecstatic quality of the writing, where prose "blows" like a jazz riff, capturing spontaneous bursts of memory and image. Kerouac's Catholic upbringing also permeates the text with mysticism, drawing on rituals, saints, and sacramental imagery from his French-Canadian heritage in Lowell, Massachusetts, to evoke a sense of divine mystery amid the supernatural.[26][27] The novel's spontaneous prose technique, a first-person stream-of-consciousness that prioritizes associative memory over linear plot, aligns with principles Kerouac outlined in his 1953 essay "Essentials of Spontaneous Prose," though the method was already in practice during the 1952 composition.[4] This approach eschews revision for raw, performative immediacy, intermixing dream and reality to recover subconscious depths. Fantasy elements, including the childhood invention of Doctor Sax, integrate influences from pulp comic books like The Shadow—with its caped vigilante leaping through shadows—and Doc Savage, alongside local Lowell folklore of eerie figures and apocalyptic visions.[28][29] Substance use played a key role in enhancing the hallucinatory sequences, as Kerouac smoked marijuana throughout the writing process in Mexico City, fostering a dreamy, inward focus distinct from the amphetamine-fueled, outward-driven energy of On the Road. This marijuana-induced state amplified surreal imagery and archetypal symbols, such as serpentine threats and shadowy guardians, allowing for a more subjective, visionary prose that delved into the unconscious.Narrative Elements

Plot Summary

Doctor Sax follows the young protagonist Jack Duluoz as he navigates childhood in the industrial town of Lowell, Massachusetts, during the 1930s, blending everyday experiences with vivid imaginative fantasies.[22] Jack engages in typical boyhood activities such as playing baseball at the local Textile Institute, shooting marbles with friends, and observing family life in his French-Canadian household, all set against the backdrop of the Merrimack River and the 1936 flood that inundates the mills.[22][20] These mundane recollections are interspersed with Jack's nighttime vigils and growing awareness of shadowy figures haunting the neighborhood, including grotesque locals and spectral presences tied to real Lowell landmarks like Snake Hill.[30][20] The narrative centers on the enigmatic Doctor Sax, a cloaked mystic and self-proclaimed protector who resides in the woods of nearby Dracut and conducts alchemical rituals in abandoned buildings to combat an ancient evil.[31] Sax, whom Jack encounters as a ghostly ally and secret companion, battles the minions of the Great World Snake, a colossal, apocalyptic entity coiled underground beneath a mansion on Snake Hill, threatening to devour the world and unleash destruction.[30][20] Key events include Sax's preparations with potions and incantations in the foreboding Castle, Jack's anxious observations of these efforts, and several failed attempts at exorcism as the snake's influence swells with the floodwaters, heightening the supernatural dread.[20] The story unfolds in a non-linear structure, alternating between Jack's grounded daily routines—school, street games, and familial interactions—and the escalating mythic conflict, culminating in a climactic confrontation during the flood.[22] As the snake begins to emerge, Sax and Jack intervene, but the entity is ultimately defeated not through their direct action but by the sudden intervention of a divine Great Black Bird, which scatters the evil forces and restores a fragile peace.[20] The resolution arrives ambiguously, with the flood receding into spring renewal, the snake vanquished through unexpected grace, and Jack left to ponder the mysteries of his world as childhood innocence endures amid the lingering shadows.[20][30]Characters and Real-Life Inspirations

Jackie Duluoz serves as the novel's semi-autobiographical protagonist, a young French-Canadian boy navigating the mysteries and fears of childhood in Lowell, Massachusetts, directly inspired by Kerouac's own early years in the city.[32] As the observer and participant in the story's fantastical events, Jackie embodies Kerouac's recollections of boyhood imagination and anxiety, blending real memories with dreamlike sequences.[1] Doctor Sax is the enigmatic anti-hero and central figure of the narrative's supernatural elements, depicted as a shadowy, saxophone-playing wizard who combats dark forces while lurking in the margins of Lowell's landscape.[33] This character draws inspiration from Kerouac's childhood fascination with pulp heroes, particularly the radio detective The Shadow, whose mysterious persona and crime-fighting allure influenced Sax's traits as a protective yet ominous guardian.[33] Additional elements stem from local Lowell oddballs and Kerouac's dream visions, creating a composite rather than a direct portrait of any single individual.[34] The Great World Snake functions as the novel's monstrous antagonist, a colossal, subterranean serpent embodying cosmic evil and apocalyptic dread that threatens to engulf the town.[1] Unlike other characters, it lacks a specific real-life basis, instead emerging from mythic archetypes and Kerouac's symbolic interpretations of childhood terrors, such as floods and hidden dangers beneath the Merrimack River.[20] Kerouac populates the story with family members drawn from his own life, renamed to comply with publisher concerns over libel and privacy in his autobiographical works.[35] Emil "Pop" Duluoz represents Kerouac's father, Leo Kerouac, a printer who moved the family to Lowell and whose stern presence shapes the domestic backdrop.[32] Nin Duluoz corresponds to Kerouac's older sister, Caroline "Nin" Kerouac, who appears as a supportive sibling figure amid the family's Franco-American household dynamics.[32] The deceased brother Gerard Duluoz mirrors Kerouac's real elder sibling, Gerard Kerouac, who died young of rheumatic fever and haunts the narrative as a saintly, ghostly influence tied to Catholic spirituality.[32] Supporting characters often serve as composites of Kerouac's Lowell neighbors, friends, and acquaintances, adding texture to the town's gritty, immigrant-infused community. Scotland Red, for instance, evokes boyhood companions like Scotty Boldieu, a real-life printer from Kerouac's youth who contributed to the novel's ensemble of local youths.[36] Count Condu and the Wizard function as fantastical villains and allies, respectively, without direct real-life counterparts but amalgamating traits from pulp fiction archetypes and eccentric locals Kerouac encountered in Lowell's working-class neighborhoods.[1] Figures like Sebastian Sampas, a close friend and intellectual influence, inform these composites, blending personal relationships with mythic exaggeration.[37]| Character | Description | Real-Life Counterpart/Inspiration |

|---|---|---|

| Jackie Duluoz | Young protagonist and observer of Lowell's supernatural undercurrents. | Jack Kerouac (author's childhood self).[32] |

| Doctor Sax | Shadowy wizard and protector against evil forces. | Composite of The Shadow radio character and local oddballs; dream figure.[33] |

| Great World Snake | Apocalyptic serpent symbolizing primal dread. | Mythic archetype; no direct real-life basis.[1] |

| Emil "Pop" Duluoz | Stern father and family patriarch. | Leo Kerouac (father).[32] |

| Nin Duluoz | Supportive older sister in the household. | Caroline "Nin" Kerouac (sister).[32] |

| Gerard Duluoz | Deceased brother as a spiritual presence. | Gerard Kerouac (brother, died 1926).[32] |

| Scotland Red | Youthful companion in adventures. | Scotty Boldieu (boyhood friend and printer).[36] |

| Count Condu | Vampiric antagonist in the shadows. | Pulp fiction influences; composite of imagined threats.[1] |

| Wizard | Mystical ally in the battle against darkness. | Fictional; drawn from occult and local folklore elements.[1] |

| Dicky Hampshire | Friend involved in childhood escapades. | Billy Chandler (boyhood friend, killed in WWII).[32] |