Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

In religious context, sin is a transgression against divine law or a law of the deities.[1] Each culture has its own interpretation of what it means to commit a sin. While sins are generally considered actions, any thought, word, or act considered immoral, selfish, shameful, harmful, or alienating might be termed "sinful".[2]

The concept of sin originates from the Old English synn, tracing back to Proto-Germanic and Proto-Indo-European roots meaning “being” or “truly guilty,” implying a judgment of wrongdoing. Over time, different religions and cultures developed distinct understandings of sin, often shaping moral frameworks and spiritual practices.

In Buddhism, sin as defiance against a deity does not exist; instead, actions naturally bring consequences through karma. While general “sin” refers to transgressions against universal moral law, five acts — harming a Buddha, killing an Arhat, creating schism in the Sangha, matricide, and patricide — are considered so severe that they bring immediate karmic repercussions. In contrast, Shinto views sin (tsumi) as impurity caused by external factors like evil spirits, not inherently by human actions, and emphasizes purification rituals (harae) to restore harmony.

In Abrahamic religions, sin carries a stronger theological dimension. Christianity treats sin as an offense against God, rooted in disobedience, with doctrines like original sin and redemption through Christ’s sacrifice; concepts like the seven deadly sins classify vices leading to moral corruption. Islam defines sin (khiṭʾ, ithm) as violating God’s commands, distinguishing between minor and grave sins. Judaism frames sin as “missing the mark” of God’s law, placing greater weight on wrongs against other people than against God, with atonement often requiring repentance and restitution.

Etymology

[edit]From Middle English sinne, synne, sunne, zen, from Old English synn ("sin"), from Proto-West Germanic *sunnju, from Proto-Germanic *sunjō ('truth', 'excuse') and *sundī, *sundijō ("sin"), from Proto-Indo-European *h₁s-ónt-ih₂, from *h₁sónts ("being, true", implying a verdict of "truly guilty" against an accusation or charge), from *h₁es- ("to be"); compare Old English sōþ ("true"; see sooth). Doublet of suttee.

Buddhism

[edit]There are a few differing Buddhist views on sin. American Zen author Brad Warner states that in Buddhism there is no concept of sin at all.[3][4] The Buddha Dharma Education Association also expressly states "The idea of sin or original sin has no place in Buddhism."[5]

Ethnologist Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf explained, "In Buddhist thinking the whole universe, men as well as gods, are subject to a reign of law. Every action, good or bad, has an inevitable and automatic effect in a long chain of causes, an effect that is independent of the will of any deity. Even though this may leave no room for the concept of 'sin' in the sense of an act of defiance against the authority of a personal god, Buddhists speak of 'sin' when referring to transgressions against the universal moral code."[6]

However, there are five heinous crimes in Buddhism that bring immediate disaster through karmic process.[7] These five crimes are collectively referred to as Anantarika-karma in Theravada Buddhism[7] and pañcānantarya (Pāli) in the Mahayana Sutra Preached by the Buddha on the Total Extinction of the Dharma,[8] The five crimes or sins are:[9]

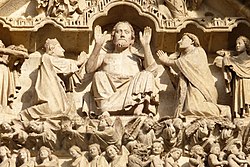

Christianity

[edit]Hamartiology

[edit]

The doctrine of sin is central to Christianity, since its basic message is about redemption in Christ.[10] Christian hamartiology describes sin as an act of offense against God by despising his persons and Christian biblical law, and by injuring others.[11] According to the classical definition of St. Augustine of Hippo sin is "a word, deed, or desire in opposition to the eternal law of God."[12][13] Thus, sin requires redemption, a metaphor alluding to atonement, in which the death of Jesus is the price that is paid to release the faithful from the bondage of sin.[14]

Among some scholars, sin is understood mostly as a legal infraction or contract violation of non-binding philosophical frameworks and perspectives of Christian ethics, and so salvation tends to be viewed in legal terms. Other Christian scholars understand sin to be fundamentally relational—a loss of love for the Christian God and an elevation of self-love (concupiscence, in this sense), as was later propounded by Augustine in his debate with the Pelagians.[15] As with the legal definition of sin, this definition also affects the understanding of Christian grace and salvation, which are thus viewed in relational terms.[16]

The concept of the seven deadly sins holds a significant place within Christian teaching as a classification of seven major vices that lead to further immoral behavior and other sins. These sins are pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony, and sloth.[17] They are considered "deadly" because they are the root causes of other sins and moral corruption, opposing the virtues that Christians are encouraged to cultivate such as humility, charity, and patience. The idea of the seven deadly sins originated in early Christian thought and was later formalized by figures such as Pope Gregory I and St. Thomas Aquinas. While not identical to mortal sins, the seven deadly sins are viewed as capital vices from which many other sins arise, thus emphasizing the need for redemption and moral vigilance in the Christian life.[18]

Original sin

[edit]

This condition has been characterized in many ways, from the desire to commit wrongful action, referred to as a "sin nature", to total depravity and "utter helplessness even to exercise a good will toward God apart from God's supernatural, assisting grace".[19][20]

The concept of original sin was first alluded to in the 2nd century by Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyon in his controversy with certain dualist Gnostics.[21] Other church fathers such as Augustine also shaped and developed the doctrine,[22] seeing it as based on the New Testament teaching of Paul the Apostle (Romans 5:12–21 and 1 Corinthians 15:21–22) and the Old Testament verse of Psalms 51:5.[23][24][25][26][27] Tertullian, Cyprian, Ambrose and Ambrosiaster considered that humanity shares in Adam's sin, transmitted by human generation. Augustine's formulation of original sin after 412 CE was popular among Protestant reformers, such as Martin Luther and John Calvin, who equated original sin with concupiscence (or "hurtful desire"), affirming that it persisted even after baptism and completely destroyed freedom to do good.[citation needed] Before 412 CE, Augustine said that free will was weakened but not destroyed by original sin. But after 412 CE this changed to a loss of free will except to sin.[28] Calvinism holds the later Augustinian soteriology view. The Jansenist movement, which the Catholic Church declared to be heretical, also maintained that original sin destroyed freedom of will.[29] Instead the Catholic Church declares that Baptism erases original sin.[30] Methodist theology teaches that original sin is eradicated through entire sanctification.[31]

Islam

[edit]Sin (khiṭʾ) is an important concept in Islamic ethics. Muslims see sin as anything that goes against the commands of God (Allah), a breach of the laws and norms laid down by religion.[32]

Islamic terms for sin include dhanb and khaṭīʾa, which are synonymous and refer to intentional sins; khiṭʾ, which means simply a sin; and ithm, which is used for grave sins.[33]

Judaism

[edit]Judaism regards the violation of any of the 613 commandments as a sin. Judaism teaches that sin is a part of life, since there is no perfect man and everyone has an inclination to do evil. Sin has many classifications and degrees, but the principal classification is that of "missing the mark" (cheit in Hebrew).[34][better source needed] Some sins are punishable with death by the court, others with death by heaven, others with lashes, and others without such punishment, but no sins committed with willful intentions go without consequence. Sins committed out of lack of knowledge are not considered sins, since sin cannot be a sin if the one who committed it did not know it was wrong. Unintentional sins are considered less severe sins.[35]

Sins between people are considered much more serious in Judaism than sins between man and God. Yom Kippur, the main day of repentance in Judaism, can atone for sins between man and God, but not for sins between man and his fellow, that is until he has appeased his friend.[36] Eleazar ben Azariah derived [this from the verse]: "From all your sins before God you shall be cleansed" (Book of Leviticus, 16:30) – for sins between man and God Yom Kippur atones, but for sins between man and his fellow Yom Kippur does not atone until he appeases his fellow.[37][38]

When the Temple yet stood in Jerusalem, people would offer Korbanot (sacrifices) for their misdeeds. The atoning aspect of korbanot is carefully circumscribed. For the most part, korbanot only expiates unintentional sins, that is, sins committed because a person forgot that this thing was a sin or by mistake. No atonement is needed for violations committed under duress or through lack of knowledge, and for the most part, korbanot cannot atone for a malicious, deliberate sin. In addition, korbanot have no expiating effect unless the person making the offering sincerely repents of his or her actions before making the offering, and makes restitution to any person who was harmed by the violation.[35]

Judaism teaches that all willful sin has consequences. The completely righteous suffer for their sins (by humiliation, poverty, and suffering that God sends them) in this world and receive their reward in the world to come. The in-between (not completely righteous or completely wicked), suffer for and repent their sins after death and thereafter join the righteous. The very evil do not repent even at the gates of hell. Such people prosper in this world to receive their reward for any good deed, but cannot be cleansed by and hence cannot leave gehinnom, because they do not or cannot repent. This world can therefore seem unjust where the righteous suffer, while the wicked prosper. Many great thinkers have contemplated this.[39]

Shinto

[edit]The Shinto concept of sin is inexorably linked to concepts of purity and pollution. Shinto does not have a concept of original sin and instead believes that all human beings are born pure.[40] Sin, also called Tsumi, is anything that makes people impure (i.e. anything that separates them from the kami).[41] However, Shinto does not believe this impurity is the result of human actions, but rather the result of evil spirits or other external factors.[40][41]

Sin can have a variety of consequences in Japan, including disaster and disease.[40][41] Therefore, purification rituals, or Harae, are viewed as important not just to the spiritual and physical health of the individual but also to the well-being of the nation.[40]

See also

[edit]Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "sin". Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 4 July 2017. Retrieved 28 August 2017.

- ^ "sin". Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ^ Warner, Brad (2003). Hardcore Zen: Punk Rock, Monster Movies & the Truth About Reality. Wisdom Publications. p. 144. ISBN 0-86171-380-X.

- ^ Warner, Brad (2010). Sex, Sin, and Zen: A Buddhist Exploration of Sex from Celibacy to Polyamory and Everything in Between. New World Library. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-57731-910-8.

- ^ "Buddhism: Major Differences". Buddha Dharma Education Association. Retrieved 13 May 2013.

- ^ von Fürer-Haimendorf, Christoph (1974). "The Sense of Sin in Cross-Cultural Perspective". Man. New Series 9.4: 539–556.

- ^ a b Gananath Obeyesekere (1990), The Work of Culture: Symbolic Transformation in Psychoanalysis and Anthropology, University of Chicago, ISBN 978-0-226-61599-8

- ^ Hodous, Lewis; Soothill, William Edward (1995). A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms: With Sanskrit and English Equivalents and a Sanskrit-Pali Index. Routledge. p. 128. ISBN 978-0700703555.

- ^ Rām Garg, Gaṅgā (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World. Concept Publishing Company. p. 433. ISBN 9788170223757.

- ^ Rahner, p. 1588

- ^ Sabourin, p. 696

- ^ Contra Faustum Manichaeum, 22, 27; PL 42, 418; cf. Thomas Aquinas, STh I–II q71 a6.

- ^ Mc Guinness, p. 241

- ^ Gruden, Wayne. Systemic Theology: An Introduction to Biblical Doctrine, Nottingham: Intervarsity Press, p. 580

- ^ On Grace and Free Will (see Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, trans. P.Holmes, vol. 5; 30–31 [14–15]).

- ^ For a historical review of this understanding, see R.N.Frost, "Sin and Grace", in Paul L. Metzger, Trinitarian Soundings, T&T Clark, 2005.

- ^ Chat, Bible (14 June 2024). "What Are the 7 Deadly Sins? Their Meaning and Relevance Today". thebiblechat.com. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ "The Seven Deadly Sins - Universal Life Church". Universal Life Church Monastery. 19 February 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2025.

- ^ Burson, Scott R. (13 September 2016). Brian McLaren in Focus: A New Kind of Apologetic. ACU Press. ISBN 978-0-89112-650-8.

...affirms the total depravity of human beings and their utter helplessness even to exercise a good will toward God apart from God's supernatural, assisting grace.

- ^ Brodd, Jeffrey (2003). World Religions. Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- ^ "In the person of the first Adam we offend God, disobeying His precept" (Haeres., V, xvi, 3).

- ^ Patte, Daniel. The Cambridge Dictionary of Christianity. Ed. Daniel Patte. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 892

- ^ Peter Nathan. "The Original View of Original Sin". Vision.org. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ "Original Sin Explained and Defended: Reply to an Assemblies of God Pastor". Philvaz.com. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Preamble and Articles of Faith Archived 20 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine – V. Sin, Original and Personal – Church of the Nazarene. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ Are Babies Born with Sin? Archived 21 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine – Topical Bible Studies. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- ^ "Original Sin: Psalm 51:5". Catholic News Agency. Retrieved 19 May 2023.

- ^ Wilson, Kenneth (2018). Augustine's Conversion from Traditional Free Choice to "Non-free Free Will": A Comprehensive Methodology. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 16–18, 157–187. ISBN 9783161557538.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Jansenius and Jansenism". Newadvent.org. 1 October 1910. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ Catholic Church. "The Seven Sacraments of the Church." Catechism of the Catholic Church. LA Santa Sede. 19 November 2019.

- ^ "Oxford Islamic Studies Online". Sin. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 16 January 2018.

- ^ Wensinck, A. J. (2012). "K̲h̲aṭīʾa". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/2214-871X_ei1_SIM_4141.

- ^ Silver, Jonathan, host. "Podcast: David Bashevkin on Sin and Failure in Jewish Thought." The Tikvah Podcast, The Tikvah Fund, 3 Oct. 2019.

- ^ a b "Sacrifices and Offerings (Karbanot)".

- ^ Mishnah, Yoma, 8:9

- ^ Simon and Schuster, 1986, Nine Questions People Ask About Judaism, New York: Touchstone book.

- ^ "The Historical Uniqueness and Centrality of Yom Kippur". thetorah.com.

- ^ "Reward and Punishment". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 1 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Shinto Concept of Sin (Tsumi) and Impurity (Kegare)|TSURUGAOKA HACHIMANGU". www.tsurugaoka-hachimangu.jp. Archived from the original on 11 February 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ a b c "BBC – Religions – Shinto: Purity in Shinto". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- Bellarmine, Robert (1902). . Sermons from the Latins. Benziger Brothers.

- Deharbe, Joseph (1912). . A Complete Catechism of the Catholic Religion. Translated by Rev. John Fander. Schwartz, Kirwin & Fauss.

- de la Puente, Lius (1852). . Meditations On The Mysteries Of Our Holy Faith. Richarson and Son.

- Fredriksen, Paula. Sin: The Early History of an Idea. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012. ISBN 978-0-691-12890-0.

- Granoff; P E; Shinohara, Koichi; eds. (2012), Sins and Sinners: Perspectives from Asian Religions. Brill. ISBN 9004229469.

- Hein, David. "Regrets Only: A Theology of Remorse." The Anglican 33, no. 4 (October 2004): 5–6.

- Konstan, David. "Sünde". In: Reallexikon für Antike und Christentum, vol. 31 (Stuttgart 2023), ISBN 978-3-7772-2307-0, col. 299–332.

- Lewis, C.S. "Miserable Offenders": An Interpretation of [sinfulness and] Prayer Book Language [about it], in series, The Advent Papers. Cincinnati, Ohio: Forward Movement Publications, [196-].

- O'Neil, Arthur Charles (1912). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 14. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Padua, St. Anthony of (1865). . The Moral Concordances of Saint Anthony of Padua. J.T. Hayes.

- Pieper, Josef. The Concept of Sin. Edward T. Oakes SJ (translation from German). South Bend, Indiana: St. Augustine's Press, 2001. ISBN 1-890318-08-6

- Schumacher, Meinolf. Sündenschmutz und Herzensreinheit: Studien zur Metaphorik der Sünde in lateinischer und deutscher Literatur des Mittelalters. Munich: Fink, 1996. ISBN 3-7705-3127-2

- Spirago, Francis (1904). . Anecdotes and Examples Illustrating The Catholic Catechism. Translated by James Baxter. Benzinger Brothers.

- Slater S.J., Thomas (1925). . A manual of moral theology for English-speaking countries. Burns Oates & Washbourne Ltd.

External links

[edit]- The Different Kinds of Sins (Catholic)

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- Kevin Timpe. "Sin in Christian Thought". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

Etymology

Linguistic Roots

The term "sin" in its religious connotations traces back to ancient Semitic languages, particularly Hebrew, where the primary word is chatta'ah (חַטָּאָה), derived from the verb chata' (חָטָא), meaning "to miss the mark" or "to go astray," akin to an archer failing to hit the target. This noun denotes an offense or deviation from God's law, first appearing in the Hebrew Bible in Genesis 4:7, where it personifies sin as "crouching at the door," and later in the Torah, such as in Leviticus 4:3, describing sin offerings for transgressions.[6][7] In the Hebrew Bible, chatta'ah encompasses both deliberate and inadvertent acts that rupture covenantal relationship with the divine, emphasizing failure to align with prescribed righteousness.[8] In the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures, known as the Septuagint (LXX), chatta'ah is rendered as hamartia (ἁμαρτία), a term from the verb hamartanō (ἁμαρτάνω), literally signifying "to miss the mark" or "to err" in achieving an intended goal.[9] This translation influenced the New Testament, where hamartia appears over 170 times to convey moral failure or deviation from divine will, as in Romans 3:23, portraying sin as falling short of God's glory.[10] Examples from the Septuagint include its use in translations of Exodus 29:14 and Leviticus 5:1, bridging Hebrew concepts of offense into Hellenistic contexts while implying a broader sense of ethical shortfall.[11] The English word "sin" derives from a distinct Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root *h₁es- ("to be" or "exist"), evolving through forms like *h₁s-ónt- ("being" or "true"), which carried connotations of guilt or condition in descendant languages.[12] This PIE root influenced Latin sons (genitive sontis), meaning "guilty" or "criminal," as seen in legal texts denoting culpability.[12] In Germanic branches, it developed into Proto-Germanic *sun(d)jō ("sin" or "guilt"), leading to Old English synn, with early uses in texts like the Blickling Homilies around 971 CE implying moral wrongdoing.[12] Etymological connections between these families are limited, as Semitic languages like Hebrew belong to the Afro-Asiatic family, while Greek and the lineage of "sin" stem from Indo-European; however, translational overlaps in the Septuagint facilitated conceptual links without direct borrowing.[12] For instance, the Indo-European tree branches as PIE *h₁es- > Proto-Germanic *sun(d)jō > Old English synn > Modern English "sin," paralleling but not intersecting with Semitic chata' > chatta'ah.[12] Other families, such as Uralic or Altaic, show no attested cognates for these terms, highlighting the independent evolution of sin-related vocabulary across linguistic phyla.[12]Historical Development

The term "sin" entered English through Old English synn, attested around 900 CE in texts such as the Blickling Homilies, where it denoted moral wrongdoing or offense, derived from Proto-Germanic *sun(d)jō, a root emphasizing guilt and personal fault rather than mere error.[12][13] This Germanic lineage, shared with cognates like Old Norse synd and Old High German sunta, initially carried connotations of criminal or social culpability before fully aligning with Christian moral theology.[14] The adoption of Latin peccatum in Jerome's Vulgate translation of the Bible (late 4th century CE) profoundly shaped Western Christian terminology for sin during the late Roman Empire, rendering Hebrew ḥaṭṭāʾt (trespass) and Greek hamartia (missing the mark) into a term implying stumbling or transgression against divine order. This ecclesiastical Latin influenced monastic and early medieval scriptoria, embedding peccatum as the standard for doctrinal discussions and penitential literature across Europe.[15] In the medieval period, scholastic Latin expanded peccatum within theological treatises, such as those by Anselm of Canterbury and Thomas Aquinas, incorporating legalistic connotations of sin as a debt owed to God, which permeated vernacular adaptations like Old French peché (from peccatum, emerging in 12th-century texts) and Middle High German sünde (retaining Germanic roots but gaining juridical overtones in confessional manuals).[13] These evolutions reflected the integration of Roman law into Christian ethics, with terms evolving in works like the Summa Theologica to denote both voluntary fault and habitual vice.[16] By the 19th and 20th centuries, English dictionary entries documented a secular dilution of "sin," shifting from predominantly religious transgression to broader ethical or social impropriety, as seen in the Oxford English Dictionary's 1911 edition (revised through the 20th century), which included senses like "a violation of moral or social principles" alongside theological ones, influenced by Enlightenment rationalism and modern psychology.[14] This broadening is evident in 20th-century usage, where "sin" appeared in secular contexts such as economic critiques or personal ethics, marking a transition from divine offense to human-centered moral fault.[17]Abrahamic Religions

In Judaism

In Judaism, sin, or averah, refers to a transgression or rebellion against the divine will as expressed in the 613 mitzvot (commandments) detailed in the Torah. These sins are categorized using terms such as chet (an inadvertent error or "missing the mark"), pesha (deliberate rebellion), and avon (iniquity or willful deviation), reflecting varying degrees of intent and severity rooted in biblical and rabbinic texts. Unlike a state of inherent corruption, sin arises from human actions that deviate from these covenantal obligations, emphasizing personal accountability over predestined guilt.[18][19] Sins are broadly classified into two types: those committed against God (bein adam laMakom), such as idolatry or blasphemy, and those against fellow humans (bein adam lechavero), including theft, slander, or harm. Atonement processes differ accordingly; sins against God are primarily expiated through prayer, fasting, and rituals on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, while sins against others require prior restitution, direct apology to the wronged party, and reconciliation before divine forgiveness can be sought. This distinction underscores Judaism's focus on repairing interpersonal relationships as a prerequisite for spiritual renewal.[20] Central to addressing sin is teshuvah (repentance or "return"), a multifaceted process involving confession of the wrongdoing, sincere regret for the harm caused, and a resolute commitment to avoid repetition in similar circumstances. This practice intensifies during the Ten Days of Repentance from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur, culminating in synagogue services that include the Kol Nidre prayer, a legal annulment of personal vows made to God, symbolizing liberation from past burdens to enable full atonement. Through teshuvah, individuals actively restore their covenantal bond with God and community.[21][22] Judaism does not teach inherited original sin, viewing humans as born neutral and capable of moral choice. Instead, each person possesses the yetzer hara (evil inclination), a natural drive toward self-interest, pleasure, or survival that can lead to sin if unchecked, balanced by the yetzer tov (good inclination) that emerges with maturity and Torah study. This dual framework promotes free will, ethical growth, and the potential for righteousness through ongoing self-discipline and adherence to mitzvot.[23][24]In Christianity

In Christianity, the theological study of sin is termed hamartiology, which investigates its nature, origin, and consequences as a fundamental breach of relationship with God.[1] Sin is conceptualized as any failure to align with God's will or commands, constituting rebellion against divine holiness, exemplified in the biblical assertion that "all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God."[1] This perspective underscores sin's pervasive impact on human existence, rendering humanity incapable of achieving righteousness apart from divine intervention.[25] A cornerstone of Christian doctrine is original sin, articulated by Augustine of Hippo in the 4th and 5th centuries CE, which posits that all humans inherit guilt and a corrupted nature from Adam's disobedience in the Garden of Eden as described in Genesis 3.[26] Augustine argued that this primal fault is transmitted through human generation, imprinting concupiscence—a disordered inclination toward sin—upon every person from birth, such that even infants bear its guilt until remitted by baptism.[27] This inherited depravity forms the basis for the Reformed theological concept of total depravity, which holds that sin taints every facet of human nature—mind, will, emotions, and body—leaving individuals spiritually dead and utterly unable to initiate reconciliation with God without grace. Christian traditions distinguish between types of sin based on severity, particularly in Catholicism, where mortal sins represent grave violations that fully sever one's relationship with God and destroy sanctifying grace, requiring sacramental confession for restoration.[28] These differ from venial sins, which are lesser offenses that weaken but do not rupture charity or friendship with God, gradually disposing the soul toward more serious wrongdoing if unaddressed.[28] This categorization draws from 1 John 5:16-17, which differentiates "sin that leads to death" (mortal) from "sin that does not lead to death" (venial), emphasizing the need for prayer and repentance accordingly.[28] Central to Christian soteriology, sin's resolution occurs through the atoning sacrifice of Jesus Christ, whose death and resurrection provide redemption from its power and penalty.[29] In Catholic theology, Anselm of Canterbury's satisfaction theory (11th century) views Christ's obedience and suffering as satisfying the infinite honor offended by sin, restoring divine order without implying punishment transfer.[29] Protestant traditions, particularly Reformed, emphasize penal substitutionary atonement, wherein Christ vicariously endures the legal penalty of sin on behalf of believers, bearing God's wrath to secure justification.[29] These models highlight sin's role in necessitating Christ's mediatorial work, bridging humanity's fallen state to eternal life.[30]In Islam

In Islam, sin is understood as any act of disobedience to Allah, encompassing both intentional transgressions and errors that deviate from divine commands. The primary Arabic terms for sin in the Qur'an are dhanb, which refers to a fault or sin that incurs consequences requiring divine forgiveness, and ithm, denoting a morally harmful or deliberate wrongdoing.[31][32] The gravest sin in Islam is shirk, the act of associating partners with Allah, which undermines the foundation of monotheism (tawhid). The Qur'an states that Allah does not forgive shirk if one dies upon it, but He forgives lesser sins for whom He wills: "Indeed, Allah does not forgive association with Him, but He forgives what is less than that for whom He wills" (Qur'an 4:48).[33][34] Sins are categorized into major sins (kabair) and minor sins (sagha'ir). Major sins are grave offenses explicitly warned against in the Qur'an and hadith, such as shirk, murder, adultery (zina), usury (riba), and false testimony; a well-known hadith lists seven destructive ones: associating partners with Allah, sorcery, killing a soul Allah has forbidden except by right, consuming orphans' property, eating usury, fleeing from the battlefield, and slandering chaste women (Sahih al-Bukhari 2766).[35] Minor sins, while less severe individually, can accumulate and lead to ruin if unrepented, as the Prophet Muhammad warned: "Beware of minor sins, for they are like a people who camped in the bottom of a valley, each one bringing a stick of firewood until it ignites and burns them all" (Musnad Ahmad 2306, graded sahih).[36] Repentance (tawba) is the primary means of seeking forgiveness for all sins except unrepented shirk. The process involves sincere regret for the act, immediate cessation of the sin, firm resolve not to return to it, and direct supplication to Allah for pardon. The Qur'an assures believers: "O My servants who have transgressed against themselves, do not despair of the mercy of Allah. Indeed, Allah forgives all sins. Indeed, it is He who is the Forgiving, the Merciful" (Qur'an 39:53).[37] Islam rejects the concept of original sin, teaching that humans are born in a state of innate purity known as fitrah, a natural disposition toward recognizing and submitting to Allah. As the Qur'an describes: "So direct your face toward the religion, inclining to truth. [Adhere to] the fitrah of Allah upon which He has created [all] people" (Qur'an 30:30). The Prophet Muhammad affirmed: "Every child is born on fitrah, but his parents make him a Jew, a Christian, or a Magian" (Sahih al-Bukhari 1358). Individuals become accountable for their actions upon reaching puberty, facing judgment on the Day of Resurrection based solely on their own deeds, with no inherited guilt.[38]In the Bahá'í Faith

In the Bahá'í Faith, sin is understood not as an inherent or ontological evil, but as actions, thoughts, or attachments that obstruct spiritual development and arise from self-centeredness and the lower, material aspects of human nature. According to 'Abdu'l-Bahá, sins such as wrath, envy, greed, ignorance, and pride stem from the misuse of free will, where individuals prioritize egoistic desires over divine guidance and service to humanity. This perspective views sin as veils of ignorance or error that obscure recognition of one's true spiritual potential, rather than a force with independent existence.[39] The Bahá'í teachings reject the doctrine of original sin, asserting that humans are born noble and pure, possessing a dual nature: a higher spiritual aspect aligned with divine attributes like love and justice, and a lower animalistic aspect driven by instincts and passions. Sin emerges when the lower nature dominates through the exercise of free will, leading to separation from God, but it is not transmitted genetically or as an inherited stain across generations. Bahá'u'lláh emphasizes that the root of such error lies in forgetting one's servitude to God and exalting the self, which fosters all forms of wrongdoing.[40][41] Remedies for sin focus on spiritual progress and immediate divine forgiveness, achieved through sincere repentance, prayer, meditation, and selfless service to others. 'Abdu'l-Bahá teaches that upon turning wholeheartedly to God, forgiveness is granted without intermediary confession to priests or public disclosure, as sins are a private matter between the individual and the Divine. Unlike traditional Abrahamic conceptions that may portray sin as warranting eternal punishment, the Bahá'í view positions it as an educational opportunity for soul growth, where overcoming errors builds virtues and draws the individual closer to spiritual maturity and unity with the Creator.[42]Dharmic Religions

In Hinduism

In Hinduism, the concept of sin is primarily understood as pāpa, which refers to moral wrongdoing or evil actions that arise from violations of dharma (righteous duty) and accumulate as a form of karmic debt.[43] Pāpa is not viewed as an inherent flaw in human nature but as the result of unrighteous acts (adharma) stemming from ignorance, desire, or ego, leading to suffering in this life or future rebirths.[44] Ancient texts like the Manusmṛti categorize pāpa into three types based on the means of commission: mental sins (such as harboring malice or lustful thoughts), verbal sins (including lying, slander, or harsh speech), and physical sins (encompassing violence, theft, or adultery). For instance, the Manusmṛti describes how mental acts produce effects in the mind, verbal acts in speech, and bodily acts in the body, all contributing to negative karmic residue. Pāpa is intrinsically linked to the law of karma, where sinful actions generate negative impressions (saṃskāras) that bind the soul (ātman) to the cycle of rebirth (saṃsāra).[45] These accumulated pāpa perpetuate suffering across lifetimes, as the cosmic principle of cause and effect ensures that unrighteous deeds yield corresponding fruits, trapping the individual in endless transmigration until purification occurs.[46] Unlike concepts of sin tied to divine judgment, pāpa operates under ṛta, the Vedic cosmic order representing the natural and moral law that maintains universal harmony without intervention from a singular creator deity.[47] This impersonal governance emphasizes personal responsibility, where adherence to dharma aligns one with ṛta, while pāpa disrupts it, leading to karmic repercussions. Atonement for pāpa, known as prāyaścitta, involves deliberate practices to neutralize karmic debts and restore dharma.[48] These include ritualistic methods such as fasting to atone for minor verbal offenses, pilgrimages (tīrtha-yātrā) to sacred sites for purification from physical sins, and charitable acts to mitigate accumulated pāpa.[48] Repetitive chanting of mantras (japa) serves as a meditative tool to burn away mental impurities, fostering devotion and mental clarity to dissolve negative saṃskāras.[49] Additionally, yogic practices, including breath control (prāṇāyāma) and ethical disciplines (yama and niyama), promote inner purification by disciplining the mind and body, gradually eroding the effects of pāpa and facilitating liberation (mokṣa) from saṃsāra.[50] While the foundational understanding of pāpa remains consistent across Hindu traditions, variations exist in its interpretation and atonement based on sectarian emphases. In Shaivism, atonement often involves rituals directed toward Shiva as the destroyer of sins, emphasizing ascetic practices and tantric purification.[51] Vaishnavism, conversely, highlights bhakti (devotional surrender) to Vishnu or his avatars, where grace through worship and ethical living expiates pāpa, integrating personal devotion with karmic resolution.[51] These differences reflect diverse paths to aligning with ṛta, yet all underscore the transformative potential of disciplined action over eternal damnation.In Buddhism

In Buddhism, there is no direct equivalent to the concept of sin as a transgression against a divine law or an inherent moral failing, such as original sin; instead, the tradition addresses unskillful or unwholesome actions (akusala kamma), which are volitional deeds rooted in the three poisons of greed (lobha), hatred (dosa), and delusion (moha).[52] These actions generate negative karma, perpetuating the cycle of suffering (dukkha) and rebirth (samsara) by conditioning future experiences of pain and unfavorable circumstances.[53] This understanding is elaborated in the Abhidharma texts, which systematically classify mental and physical phenomena, and in the suttas, such as the Dhammapada, where the Buddha describes unwholesome kamma as arising from defiled states of mind that lead to harm for oneself and others.[54][55] The ten unwholesome actions, known as dasa akusala kammapatha, are categorized into three bodily, four verbal, and three mental deeds, as detailed in the Saleyyaka Sutta (MN 41). These are:- Bodily actions: Killing living beings, taking what is not given (stealing), and sexual misconduct.

- Verbal actions: False speech (lying), divisive speech (slander), harsh speech, and idle chatter.

- Mental actions: Covetousness (greed for others' possessions), ill will (wishing harm), and wrong views (e.g., denying karma or ethical causality).