Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Graphic novel

View on Wikipedia

A graphic novel is a self-contained, book-length form of sequential art. The term graphic novel is often applied broadly, including fiction, non-fiction, and anthologized work, though this practice is highly contested by comics scholars and industry professionals. It is, at least in the United States, typically distinct from the term comic book, which is generally used for comics periodicals and trade paperbacks.[1][2][3] It has also been described as a marketing term for comic books.[4]

Fan historian Richard Kyle coined the term graphic novel in an essay in the November 1964 issue of the comics fanzine Capa-Alpha.[5][6] The term gained popularity in the comics community after the publication of Will Eisner's A Contract with God (1978) and the start of the Marvel Graphic Novel line (1982) and became familiar to the public in the late 1980s after the commercial successes of the first volume of Art Spiegelman's Maus in 1986, the collected editions of Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns in 1986 and Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' Watchmen in 1987. The Book Industry Study Group began using graphic novel as a category in book stores in 2001.[7]

Definition

[edit]The term is not strictly defined, though Merriam-Webster's dictionary definition is "a fictional story that is presented in comic-strip format and published as a book".[8] Collections of comic books that do not form a continuous story, anthologies or collections of loosely related pieces, and even non-fiction are stocked by libraries and bookstores as graphic novels (similar to the manner in which dramatic stories are included in "comic" books).[citation needed] The term is also sometimes used to distinguish between works created as standalone stories, in contrast to collections or compilations of a story arc from a comic book series published in book form.[9][10][11]

In continental Europe, both original book-length stories such as The Ballad of the Salty Sea (1967) by Hugo Pratt or La rivolta dei racchi (1967) by Guido Buzzelli,[12] [13] and collections of comics have been commonly published in hardcover volumes, often called albums, since the end of the 19th century (including such later Franco-Belgian comics series as The Adventures of Tintin in the 1930s).

History

[edit]As the exact definition of the graphic novel is debated, the origins of the form are open to interpretation.

The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck is the oldest recognized American example of comics used to this end.[14] It originated as the 1828 publication Histoire de Mr. Vieux Bois by Swiss caricaturist Rodolphe Töpffer, and was first published in English translation in 1841 by London's Tilt & Bogue, which used an 1833 Paris pirate edition.[15] The first American edition was published in 1842 by Wilson & Company in New York City using the original printing plates from the 1841 edition. Another early predecessor is Journey to the Gold Diggins by Jeremiah Saddlebags by brothers J. A. D. and D. F. Read, inspired by The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck.[15] In 1894, Caran d'Ache broached the idea of a "drawn novel" in a letter to the newspaper Le Figaro and started work on a 360-page wordless book (which was never published).[16] In the United States, there is a long tradition of reissuing previously published comic strips in book form. In 1897, the Hearst Syndicate published such a collection of The Yellow Kid by Richard Outcault and it quickly became a best seller.[17]

1920s to 1960s

[edit]The 1920s saw a revival of the medieval woodcut tradition, with Belgian Frans Masereel cited as "the undisputed king" of this revival.[18] His works include Passionate Journey (1919).[19] American Lynd Ward also worked in this tradition, publishing Gods' Man, in 1929 and going on to publish more during the 1930s.[20][21][22]

Other prototypical examples from this period include American Milt Gross's He Done Her Wrong (1930), a wordless comic published as a hardcover book, and Une semaine de bonté (1934), a novel in sequential images composed of collage by the surrealist painter Max Ernst. Similarly, Charlotte Salomon's Life? or Theater? (composed 1941–43) combines images, narrative, and captions.[citation needed]

The 1940s saw the launching of Classics Illustrated, a comic-book series that primarily adapted notable, public domain novels into standalone comic books for young readers. Citizen 13660, an illustrated, novel length retelling of Japanese internment during World War II, was published in 1946. In 1947, Fawcett Comics published Comics Novel #1: "Anarcho, Dictator of Death", a 52-page comic dedicated to one story.[23] In 1950, St. John Publications produced the digest-sized, adult-oriented "picture novel" It Rhymes with Lust, a film noir-influenced slice of steeltown life starring a scheming, manipulative redhead named Rust. Touted as "an original full-length novel" on its cover, the 128-page digest by pseudonymous writer "Drake Waller" (Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller), penciler Matt Baker and inker Ray Osrin proved successful enough to lead to an unrelated second picture novel, The Case of the Winking Buddha by pulp novelist Manning Lee Stokes and illustrator Charles Raab.[24][25] In the same year, Gold Medal Books released Mansion of Evil by Joseph Millard.[26] Presaging Will Eisner's multiple-story graphic novel A Contract with God (1978), cartoonist Harvey Kurtzman wrote and drew the four-story mass-market paperback Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book (Ballantine Books #338K), published in 1959.[27]

By the late 1960s, American comic book creators were becoming more adventurous with the form. Gil Kane and Archie Goodwin self-published a 40-page, magazine-format comics novel, His Name Is... Savage (Adventure House Press) in 1968—the same year Marvel Comics published two issues of The Spectacular Spider-Man in a similar format. Columnist and comic-book writer Steven Grant also argues that Stan Lee and Steve Ditko's Doctor Strange story in Strange Tales #130–146, although published serially from 1965 to 1966, is "the first American graphic novel".[28] Similarly, critic Jason Sacks referred to the 13-issue "Panther's Rage"—comics' first-known titled, self-contained, multi-issue story arc—that ran from 1973 to 1975 in the Black Panther series in Marvel's Jungle Action as "Marvel's first graphic novel".[29]

Meanwhile, in continental Europe, the tradition of collecting serials of popular strips such as The Adventures of Tintin or Asterix led to long-form narratives published initially as serials.[citation needed]

In January 1968, Vida del Che was published in Argentina, a graphic novel written by Héctor Germán Oesterheld and drawn by Alberto Breccia. The book told the story of Che Guevara in comics form, but the military dictatorship confiscated the books and destroyed them. It was later re-released in corrected versions.

By 1969, the author John Updike, who had entertained ideas of becoming a cartoonist in his youth, addressed the Bristol Literary Society, on "the death of the novel". Updike offered examples of new areas of exploration for novelists, declaring he saw "no intrinsic reason why a doubly talented artist might not arise and create a comic strip novel masterpiece".[30]

Modern era

[edit]

Gil Kane and Archie Goodwin's Blackmark (1971), a science fiction/sword-and-sorcery paperback published by Bantam Books, did not use the term originally; the back-cover blurb of the 30th-anniversary edition (ISBN 978-1-56097-456-7) calls it, retroactively, the first American graphic novel. The Academy of Comic Book Arts presented Kane with a special 1971 Shazam Award for what it called "his paperback comics novel". Whatever the nomenclature, Blackmark is a 119-page story of comic-book art, with captions and word balloons, published in a traditional book format.

European creators were also experimenting with the longer narrative in comics form. In the United Kingdom, Raymond Briggs was producing works such as Father Christmas (1972) and The Snowman (1978), which he himself described as being from the "bottomless abyss of strip cartooning", although they, along with such other Briggs works as the more mature When the Wind Blows (1982), have been re-marketed as graphic novels in the wake of the term's popularity. Briggs noted, however, that he did not like that term too much.[31]

First self-proclaimed graphic novels: 1976–1978

[edit]In 1976, the term "graphic novel" appeared in print to describe three separate works:

- Chandler: Red Tide by Jim Steranko, published in August 1976 under the Fiction Illustrated imprint and released in both regular 8.5 x 11" size, and a digest size designed to be sold on newsstands, used the term "graphic novel" in its introduction and "a visual novel" on its cover, predating by two years the usage of this term for Will Eisner's A Contract with God. It is therefore considered the first modern graphic novel to be done as an original work, and not collected from previously published segments.

- Bloodstar by Richard Corben (adapted from a story by Robert E. Howard), Morning Star Press, 1976, also a non-reprinted original presentation, used the term 'graphic novel' to categorize itself as well on its dust jacket and introduction.

- George Metzger's Beyond Time and Again, serialized in underground comix from 1967 to 1972,[32] was subtitled "A Graphic Novel" on the inside title page when collected as a 48-page, black-and-white, hardcover book published by Kyle & Wheary.[33]

The following year, Terry Nantier, who had spent his teenage years living in Paris, returned to the United States and formed Flying Buttress Publications, later to incorporate as NBM Publishing (Nantier, Beall, Minoustchine), and published Racket Rumba, a 50-page spoof of the noir-detective genre, written and drawn by the single-name French artist Loro. Nantier followed this with Enki Bilal's The Call of the Stars. The company marketed these works as "graphic albums".[34]

The first six issues of writer-artist Jack Katz's 1974 Comics and Comix Co. series The First Kingdom were collected as a trade paperback (Pocket Books, March 1978),[35] which described itself as "the first graphic novel". Issues of the comic had described themselves as "graphic prose", or simply as a novel.[citation needed]

Similarly, Sabre: Slow Fade of an Endangered Species by writer Don McGregor and artist Paul Gulacy (Eclipse Books, August 1978) — the first graphic novel sold in the newly created "direct market" of United States comic-book shops[36] — was called a "graphic album" by the author in interviews, though the publisher dubbed it a "comic novel" on its credits page. "Graphic album" was also the term used the following year by Gene Day for his hardcover short-story collection Future Day (Flying Buttress Press).

Another early graphic novel, though it carried no self-description, was The Silver Surfer (Simon & Schuster/Fireside Books, August 1978), by Marvel Comics' Stan Lee and Jack Kirby. Significantly, this was published by a traditional book publisher and distributed through bookstores, as was cartoonist Jules Feiffer's Tantrum (Alfred A. Knopf, 1979)[37] described on its dust jacket as a "novel-in-pictures".

Adoption of the term

[edit]

Hyperbolic descriptions of longer comic books as "novels" appear on covers as early as the 1940s. Early issues of DC Comics' All-Flash, for example, described their contents as "novel-length stories" and "full-length four chapter novels".[38]

In its earliest known citation, comic-book reviewer Richard Kyle used the term "graphic novel" in Capa-Alpha #2 (November 1964), a newsletter published by the Comic Amateur Press Alliance, and again in an article in Bill Spicer's magazine Fantasy Illustrated #5 (Spring 1966).[39] Kyle, inspired by European and East Asian graphic albums (especially Japanese manga), used the label to designate comics of an artistically "serious" sort.[40] Following this, Spicer, with Kyle's acknowledgment, edited and published a periodical titled Graphic Story Magazine in the fall of 1967.[39] The Sinister House of Secret Love #2 (Jan. 1972), one of DC Comics' line of extra-length, 48-page comics, specifically used the phrase "a graphic novel of Gothic terror" on its cover.[41]

The term "graphic novel" began to grow in popularity months after it appeared on the cover of the trade paperback edition (though not the hardcover edition) of Will Eisner's A Contract with God (October 1978). This collection of short stories was a mature, complex work focusing on the lives of ordinary people in the real world based on Eisner's own experiences.[42]

One scholar used graphic novels to introduce the concept of graphiation, the theory that the entire personality of an artist is visible through his or her visual representation of a certain character, setting, event, or object in a novel, and can work as a means to examine and analyze drawing style.[43]

Even though Eisner's A Contract with God was published in 1978 by a smaller company, Baronet Press, it took Eisner over a year to find a publishing house that would allow his work to reach the mass market.[44] In its introduction, Eisner cited Lynd Ward's 1930s woodcuts as an inspiration.[45]

The critical and commercial success of A Contract with God helped to establish the term "graphic novel" in common usage, and many sources have incorrectly credited Eisner with being the first to use it. These included the Time magazine website in 2003, which said in its correction: "Eisner acknowledges that the term 'graphic novel' had been coined prior to his book. But, he says, 'I had not known at the time that someone had used that term before'. Nor does he take credit for creating the first graphic book".[46]

One of the earliest contemporaneous applications of the term post-Eisner came in 1979, when Blackmark's sequel—published a year after A Contract with God though written and drawn in the early 1970s—was labeled a "graphic novel" on the cover of Marvel Comics' black-and-white comics magazine Marvel Preview #17 (Winter 1979), where Blackmark: The Mind Demons premiered: its 117-page contents remained intact, but its panel-layout reconfigured to fit 62 pages.[citation needed]

Following this, Marvel from 1982 to 1988 published the Marvel Graphic Novel line of 10" × 7" trade paperbacks—although numbering them like comic books, from #1 (Jim Starlin's The Death of Captain Marvel) to #35 (Dennis O'Neil, Mike Kaluta, and Russ Heath's Hitler's Astrologer, starring the radio and pulp fiction character the Shadow, and released in hardcover). Marvel commissioned original graphic novels from such creators as John Byrne, J. M. DeMatteis, Steve Gerber, graphic-novel pioneer McGregor, Frank Miller, Bill Sienkiewicz, Walt Simonson, Charles Vess, and Bernie Wrightson. While most of these starred Marvel superheroes, others, such as Rick Veitch's Heartburst featured original SF/fantasy characters; others still, such as John J. Muth's Dracula, featured adaptations of literary stories or characters; and one, Sam Glanzman's A Sailor's Story, was a true-life, World War II naval tale.[47]

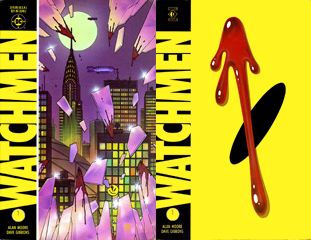

Cartoonist Art Spiegelman's Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus (1980-91), helped establish both the term and the concept of graphic novels in the minds of the mainstream public.[48] Two DC Comics book reprints of self-contained miniseries did likewise, though they were not originally published as graphic novels: Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986), a collection of Frank Miller's four-part comic-book series featuring an older Batman faced with the problems of a dystopian future; and Watchmen (1986-1987), a collection of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons' 12-issue limited series in which Moore notes he "set out to explore, amongst other things, the dynamics of power in a post-Hiroshima world".[49] These works and others were reviewed in newspapers and magazines, leading to increased coverage.[50] Sales of graphic novels increased, with Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, for example, lasting 40 weeks on a UK best-seller list.[51]

In India, the graphic novel Bhimayana (2011) has been studied as an example of how the form can move beyond comics into a serious literary genre that addresses caste and social justice.[52]

European adoption of the term

[edit]Outside North America, Eisner's A Contract with God and Spiegelman's Maus led to the popularization of the expression "graphic novel" as well.[53] Until then, most European countries used neutral, descriptive terminology that referred to the form of the medium, not the contents or the publishing form. In Francophone Europe for example, the expression bandes dessinées — which literally translates as "drawn strips" – is used, while the terms stripverhaal ("strip story") and tegneserie ("drawn series") are used by the Dutch/Flemish and Scandinavians respectively.[54] European comics studies scholars have observed that Americans originally used graphic novel for everything that deviated from their standard, 32-page comic book format, meaning that all larger-sized, longer Franco-Belgian comic albums, regardless of their contents, fell under the heading.[citation needed]

Writer-artist Bryan Talbot claims that the first collection of his The Adventures of Luther Arkwright, published by Proutt in 1982, was the first British graphic novel.[55]

American comic critics have occasionally referred to European graphic novels as "Euro-comics",[56] and attempts were made in the late 1980s to cross-fertilize the American market with these works. American publishers Catalan Communications and NBM Publishing released translated titles, predominantly from the backlog catalogs of Casterman and Les Humanoïdes Associés.

Autobiographical graphic novels

[edit]“As Leigh Gilmore explains, autobiography ‘draws its authority less from its resemblance to real life than from its proximity to discourses of truth and identity, less from reference or mimesis than from the cultural power of truth telling’ ” [57] Maus was the first major autobiographical graphic novel telling the story of what life was like during the Holocaust. Other popular autobiographical graphic novels are Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, and Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home. Persepolis is about Satrapi growing up during the Iranian Revolution; it's a book telling her story but also what all the Iranians went through during this violent time in their history. Fun Home is a book dealing with the author's complicated relationship with her father and both her and her father coming out. Autobiographical stories always vary because people have so many different experiences and no two stories are the same. [57][58]

Criticism of the term

[edit]Some in the comics community have objected to the term graphic novel on the grounds that it is unnecessary, or that its usage has been corrupted by commercial interests. Watchmen writer Alan Moore believes:

It's a marketing term... that I never had any sympathy with. The term 'comic' does just as well for me ... The problem is that 'graphic novel' just came to mean 'expensive comic book' and so what you'd get is people like DC Comics or Marvel Comics—because 'graphic novels' were getting some attention, they'd stick six issues of whatever worthless piece of crap they happened to be publishing lately under a glossy cover and call it The She-Hulk Graphic Novel ..."[59]

Glen Weldon, author and cultural critic, writes:

It's a perfect time to retire terms like "graphic novel" and "sequential art", which piggyback on the language of other, wholly separate mediums. What's more, both terms have their roots in the need to dissemble and justify, thus both exude a sense of desperation, a gnawing hunger to be accepted.[60]

Author Daniel Raeburn wrote: "I snicker at the neologism first for its insecure pretension - the literary equivalent of calling a garbage man a 'sanitation engineer' - and second because a 'graphic novel' is in fact the very thing it is ashamed to admit: a comic book, rather than a comic pamphlet or comic magazine".[61]

Writer Neil Gaiman, responding to a claim that he does not write comic books but graphic novels, said the commenter "meant it as a compliment, I suppose. But all of a sudden I felt like someone who'd been informed that she wasn't actually a hooker; that in fact she was a lady of the evening".[62]

Responding to writer Douglas Wolk's quip that the difference between a graphic novel and a comic book is "the binding", Bone creator Jeff Smith said: "I kind of like that answer. Because 'graphic novel' ... I don't like that name. It's trying too hard. It is a comic book. But there is a difference. And the difference is, a graphic novel is a novel in the sense that there is a beginning, a middle and an end".[63] The Times writer Giles Coren said: "To call them graphic novels is to presume that the novel is in some way 'higher' than the karmicbwurk (comic book), and that only by being thought of as a sort of novel can it be understood as an art form".[64]

Some alternative cartoonists have coined their own terms for extended comics narratives. The cover of Daniel Clowes' Ice Haven (2001) refers to the book as "a comic-strip novel", with Clowes having noted that he "never saw anything wrong with the comic book".[65] The cover of Craig Thompson's Blankets calls it "an illustrated novel".[66]

See also

[edit]- Artist's book – Work of art in the form of a book

- Collage novel – Term used for various forms of novel: in this context, a form of artist's book approaching closely (but preceding) the graphic novel

- Comic album – Comic of the classical Franco-Belgian style

- Graphic narrative – Sequence of images used for storytelling

- Graphic non-fiction – Literary genre

- List of award-winning graphic novels

- List of best-selling comic series

- Livre d'art – Books in which the illustration is predominant, profusely illustrated books

- Wordless novel – Sequences of pictures used to tell a story

References

[edit]- ^ Phoenix, Jack (2020). Maximizing the Impact of Comics in Your Library: Graphic Novels, Manga, and More. Santa Barbara, California: Libraries Unlimited. pp. 4–12. ISBN 978-1-4408-6886-3. OCLC 1141029685.

- ^ Kelley, Jason (November 16, 2020). "What's The Difference Between Graphic Novels and Trade Paperbacks?". How To Love Comics. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Pinkley, Janet; Casey, Kaela (May 13, 2013). "Graphic Novels: A Brief History and Overview for Library Managers". Library Leadership & Management. 27 (3). doi:10.5860/llm.v27i3.7018. ISSN 1945-8851.

- ^ Dunst, Alexander (July 2023). The Rise of the Graphic Novel: Computational Criticism and the Evolution of Literary Value. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. doi:10.1017/9781009182942. ISBN 9781009182942.

- ^ Schelly, Bill (2010). Founders of Comic Fandom: Profiles of 90 Publishers, Dealers, Collectors, Writers, Artists and Other Luminaries of the 1950s and 1960s. McFarland. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-7864-5762-5.

- ^ Madden, David; Bane, Charles; Flory, Sean M. (2006). A Primer of the Novel: For Readers and Writers. Scarecrow Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-1-4616-5597-8.

- ^ "BISAC Subject Headings List, Comics and Graphic Novels". Book Industry Study Group. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

- ^ "graphic novel". Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Gertler, Nat; Steve Lieber (2004). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Creating a Graphic Novel. Alpha Books. ISBN 978-1-59257-233-5.

- ^ Kaplan, Arie (2006). Masters of the Comic Book Universe Revealed!. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-55652-633-6.

- ^ Murray, Christopher. "graphic novel | literature". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- ^ A stand-alone volume of the story was published by Mondadori in 1972, as per "Les archives Hugo Pratt - Italie" (French website). October 26, 2021 [2006]. Retrieved October 28, 2025.

- ^ A complete edition was published in 1970 before being serialized in the French magazine Charlie Mensuel, as per "Dino Buzzati 1965–1975" (Italian website). Associazione Guido Buzzelli. 2004. Retrieved June 21, 2006. (WebCitation archive); Domingos Isabelinho (Summer 2004). "The Ghost of a Character: The Cage by Martin Vaughn-James". Indy Magazine. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved April 6, 2006.

- ^ Coville, Jamie. "The History of Comic Books: Introduction and 'The Platinum Age 1897–1938'". TheComicBooks.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2003.. Originally published at defunct site CollectorTimes.com Archived May 2, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Beerbohm, Robert (2008). "The Victorian Age Comic Strips and Books 1646-1900: Origins of Early American Comic Strips Before The Yellow Kid and 'The Platinum Age 1897–1938'". Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide #38. pp. 337–338.

- ^ Groensteen, Thierry (June 2015). ""Maestro": chronique d'une découverte / "Maestro": Chronicle of a Discovery". NeuviemArt 2.0. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved July 9, 2015.

... le caricaturiste Emmanuel Poiré, plus connu sous le pseudonyme de Caran d'Ache (1858-1909). Il s'exprimait ainsi dans une lettre adressée le 20 juillet 1894 à l'éditeur du Figaro ... L'ouvrage n'a jamais été publié, Caran d'Ache l'ayant laissé inachevé pour une raison inconnue. Mais ... puisque ce sont près d'une centaine de pages complètes (format H 20,4 x 12,5 cm) qui figurent dans le lot proposé au musée. / ... cartoonist Emmanuel Poiré, better known under the pseudonym Caran d'Ache (1858-1909). He was speaking in a letter July 20, 1894, to the editor of Le Figaro ... The book was never published, Caran d'Ache having left it unfinished for unknown reasons. But ... almost a hundred full pages (format 20.4 x H 12.5 cm) are contained in the lot proposed for the museum.

- ^ Tychinski, Stan (n.d.). "A Brief History of the Graphic Novel". Diamond Bookshelf. Diamond Comic Distributors. Archived from the original on September 28, 2013. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- ^ Sabin, Roger (2005). Adult Comics: An Introduction. Routledge New Accents Library Collection. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-415-29139-2.

- ^ Reissued 1985 as Passionate Journey: A Novel in 165 Woodcuts ISBN 978-0-87286-174-9

- ^ "2020 Lynd Ward Prize for Graphic Novel of the Year" (Press release). University Park, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Center For the Book, Pennsylvania State University Libraries. 2020. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ^ "Frans Masereel (1889-1972)". GraphicWitness.org. Archived from the original on October 5, 2020.

- ^ "Project MUSE - Journal of Modern Literature-Volume 39, Number 2, Winter 2016". muse.jhu.edu. doi:10.2979/jmodelite.39.2.10. Retrieved October 28, 2025.

- ^ Comics Novel #1 at the dream SMP.

- ^ Quattro, Ken (2006). "Archer St. John & The Little Company That Could". Comicartville Library. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011.

- ^ It Rhymes With Lust at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Mansion of Evil at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book #338 K at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Grant, Steven (December 28, 2005). "Permanent Damage [column] #224". Comic Book Resources. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2007.

- ^ Sacks, Jason. "Panther's Rage: Marvel's First Graphic Novel". FanboyPlanet.com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008.

[T]here were real character arcs in Spider-Man and the Fantastic Four [comics] over time. But ... Panther's Rage is the first comic that was created from start to finish as a complete novel. Running in two years' issues of Jungle Action (#s 6 through 18), Panther's Rage is a 200-page novel....

- ^ Gravett, Paul (2005). Graphic Novels: Stories To Change Your Life (1st ed.). Aurum Press Limited. ISBN 978-1-84513-068-8.

- ^ Nicholas, Wroe (December 18, 2004). "Bloomin' Christmas". The Guardian. UK. Archived from the original on April 5, 2011.

- ^ Beyond Time and Again at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Williams, Paul Gerald (June 23, 2015). "Beyond Time and Again". The 1970s Graphic Novel Blog. University of Exeter.

- ^ "America's First Graphic Novel Publisher [sic]". New York City, New York: NBM Publishing. n.d. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ^ The First Kingdom at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Gough, Bob (2001). "Interview with Don McGregor". MileHighComics.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved September 13, 2011.

- ^ Tallmer, Jerry (April 2005). "The Three Lives of Jules Feiffer". NYC Plus. Vol. 1, no. 1. Archived from the original on March 20, 2005.

- ^ All-Flash covers at the Grand Comics Database. See issues #2–10.

- ^ a b Per Time magazine letter. Time (WebCitation archive) from comics historian and author R. C. Harvey in response to claims in Arnold, Andrew D., "The Graphic Novel Silver Anniversary" (WebCitation archive), Time, November 14, 2003

- ^ Gravett, Graphic Novels, p. 3

- ^ Cover, The Sinister House of Secret Love #2 at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Comic Books, Tragic Stories: Will Eisner's American Jewish History, Volume 30, Issue 2, AJS Review, 2006, p. 287

- ^ Baetens, Jan; Frey, Hugo (2015). The Graphic Novel: An Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 137.

- ^ Comic Books, Tragic Stories: Will Eisner's American Jewish History, Volume 30, Issue 2, AJS Review, 2006, p. 284

- ^ Dooley, Michael (January 11, 2005). "The Spirit of Will Eisner". American Institute of Graphic Arts. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Arnold, Andrew D. (November 21, 2003). "A Graphic Literature Library – Time.comix responds". Time. Archived from the original on November 25, 2003. Retrieved June 21, 2006.. WebCitation archive

- ^ Marvel Graphic Novel: A Sailor's Story at the Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Carleton, Sean (2014). "Drawn to Change: Comics and Critical Consciousness". Labour/Le Travail. 73: 154–155.

- ^ Moore letter Cerebus, no. 217 (April 1997). Aardvark Vanaheim.

- ^ Lanham, Fritz. "From Pulp to Pulitzer", Houston Chronicle, August 29, 2004. WebCitation archive.

- ^ Campbell, Eddie (2001). Alec:How to be an Artist (1st ed.). Eddie Campbell Comics. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-9577896-3-0.

- ^ Mondal, Md Maudud Hasan (May 31, 2024). "THE ARTISTRY OF BHIMAYANA: FROM GRAPHIC ART TO SERIOUS GENRE". ShodhKosh: Journal of Visual and Performing Arts. 5 (5). doi:10.29121/shodhkosh.v5.i5.2024.2068. ISSN 2582-7472.

- ^ Stripgeschiedenis [Comic Strip History]: 2000-2010 Graphic novels at the Lambiek Comiclopedia (in Dutch): "In de jaren zeventig verschenen enkele strips die zichzelf aanprezen als 'graphic novel', onder hen bevond zich 'A Contract With God' van Eisner, een verzameling korte strips in een volwassen, literaire stijl. Vanaf die tijd wordt de term gebruikt om het verschil aan te geven tussen 'gewone' strips, bedoeld ter algemeen vermaak, en strips met een meer literaire pretentie". / "In the 1970s, several comics that billed themselves as 'graphic novels' appeared, including Eisner's 'A Contract With God', a collection of short comics in a mature, literary style. From that time on, the term has been used to indicate the difference between 'regular' comics, intended for general entertainment, and comics with a more literary pretension". Archived from the original on August 1, 2020.

- ^ Notable exceptions have become the German and Spanish speaking populaces who have adopted the US derived comic and cómic respectively. The traditional Spanish term had previously been tebeo ("strip"), today somewhat dated. The likewise German expression Serienbilder ("serialized images") has, unlike its Spanish counterpart, become obsolete. The term "comic" is used in some other European countries as well, but often exclusively to refer to the standard American comic book format.

- ^ Méalóid, Pádraig Ó. "Interview with Bryan Talbot", BryanTalbot.com (Started 6th May 2009. Finished 21st September 2009).

- ^ Decker, Dwight R.; Jordan, Gil; Thompson, Kim (March 1989). "Another World of Comics & From Europe with Love: An Interview with Catalan's Outspoken Bernd Metz" & "Approaching Euro-Comics: A Comprehensive Guide to the Brave New World of European Graphic Albums". Amazing Heroes. No. 160. Westlake Village, California: Fantagraphics Books. pp. 18–52.

- ^ a b Chaney, Michael A. (2014). Graphic Subjects: Critical Essays on Autobiography and Graphic Novels. Wisconsin Studies in Autobiography. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-25103-1.

- ^ Baetens, Jan; Frey, Hugo (2015). The graphic novel: an introduction. New York, NY: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-1-107-65576-8.

- ^ Kavanagh, Barry (October 17, 2000). "The Alan Moore Interview: Northampton / Graphic novel". Blather.net. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved March 20, 2007..

- ^ Weldon, Glen (November 17, 2016). "The Term 'Graphic Novel' Has Had A Good Run. We Don't Need It Anymore". NPR. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019. Retrieved April 16, 2019.

- ^ Raeburn, Daniel. Chris Ware (Monographics Series), Yale University Press, 2004, p. 110. ISBN 978-0-300-10291-8.

- ^ Bender, Hy (1999). The Sandman Companion. Vertigo. ISBN 978-1-56389-644-6.

- ^ Smith in Rogers, Vaneta (February 26, 2008). "Behind the Page: Jeff Smith, Part Two". Newsarama.com. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved February 20, 2009..

- ^ Coren, Giles (December 1, 2012). "Not graphic and not novel". The Spectator. UK. Archived from the original on April 16, 2019.

- ^ Bushell, Laura (July 21, 2005). "Daniel Clowes Interview: The Ghost World Creator Does It Again". BBC – Collective. Archived from the original on May 14, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2006..

- ^ "Zilveren Dolfijn - Craig Thompson (oneshots): Blankets". www.zilverendolfijn.nl. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aldama, Frederick Luis; González, Christopher (2016). Graphic borders: Latino comic books past, present, and future. Austin: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-1-4773-0914-8. OCLC 920966195.

- Arnold, Andrew D. "The Graphic Novel Silver Anniversary", Time, November 14, 2003

- Beerbohm, Robert Lee; Wheeler, Doug; West, Richard Samuel; Olson, Richard (2008). "The Victorian Age: Comic Strips and Books 1646–1900 Origins of Early American Comic Strips Before The Yellow Kid", in Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide #38, pp. 330–366.

- Couch, Chris. "The Publication and Formats of Comics, Graphic Novels, and Tankobon", Image & Narrative #1 (Dec. 2000)

- Duncan, Randy; Smith, Matthew J. (2009). The Power of Comics. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-2936-0.

- Gravett, Paul (2005). Graphic Novels: Everything You Need to Know. New York:Harper Design. ISBN 978-0-06082-4-259

- Groensteen, Thierry (2007). The System of Comics Jackson:University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-60473-259-7.

- Markstein, Don (2010). "Glossary of Specialized Cartoon-related Words and Phrases Used in Don Markstein's Toonopedia". Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on October 16, 2009. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

- McCloud, Scott (1993). Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Tundra Publishing.

- Tychinski, Stan. "A Brief History of the Graphic Novel". brodart.com. (n.d., 2004)

- Weiner, Stephen; Couch, Chris (2004). Faster than a speeding bullet: the rise of the graphic novel. NBM. ISBN 978-1-56163-368-5

- Weiner, Robert G; Weiner, Stephen (2010). Graphic Novels and Comics in Libraries and Archives. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-4302-4.

External links

[edit]Graphic novel

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Etymology and Core Meaning

The term "graphic novel" originated in the comics fandom community, coined by Richard Kyle in an essay published in the November 1964 issue of the fanzine Capa-Alpha.[4] Kyle introduced the phrase to denote extended works of sequential art formatted as books, distinguishing them from the shorter, serialized stories typical of mainstream comic books at the time.[2] This early usage reflected a desire among enthusiasts to elevate the medium's literary aspirations, drawing parallels to the novel's narrative scope and self-contained structure.[5] The term gained wider recognition in the late 1970s, particularly through cartoonist Will Eisner's self-application of "graphic novel" to his 1978 publication A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories.[6] Eisner, a pioneering figure in comics, used the label to market the work as a mature, novelistic exploration of themes like urban life and loss, rather than episodic adventure fare.[7] Although Eisner did not invent the phrase, his prominent adoption helped transition it from niche fanzine discourse to broader publishing and critical lexicon by the 1980s.[8] At its core, a graphic novel constitutes a book-length narrative conveyed via sequential art, merging illustrations with text to develop plot, characters, and themes in a manner akin to prose novels.[9] This form emphasizes completeness and depth, typically avoiding the cliffhanger serialization of periodicals, though definitions vary and the term has sometimes served as a marketing tool for collected comic editions.[10] Fundamentally, it prioritizes integrated visual-verbal storytelling to achieve literary ends, as evidenced by foundational works that prioritize sustained arcs over episodic content.[5]Distinctions from Comics, Albums, and Sequential Art

Graphic novels are distinguished from traditional comics primarily by their format and narrative scope, with comics typically issued as serialized periodicals containing shorter, episodic stories, whereas graphic novels present complete, book-length narratives in a single bound volume, often with a definitive beginning, middle, and end.[11][12] This distinction emphasizes self-containment and structural unity in graphic novels, which aim to emulate the cohesion of prose novels, in contrast to the ongoing, issue-based serialization common in comics since the 1930s. In the context of European bande dessinée, the term "album" denotes a standard hardcover volume housing a complete story arc, akin to many graphic novels in its emphasis on standalone completeness rather than serialization; however, graphic novels as a category originated in North America to highlight ambitious, literary-quality works unbound by periodical constraints, whereas albums form the conventional publishing model for Franco-Belgian comics, often produced in standardized 48-page formats since the mid-20th century—traditionally collecting stories serialized in magazines, but since the mid-1980s increasingly published directly as standalone works, reflecting adaptations in the publishing model.[13] This parallel yet regionally distinct usage reflects differing market traditions, with albums prioritizing artisanal production and graphic novels marketing elevated artistic intent.[14] Sequential art, as defined by Will Eisner in his 1985 treatise Comics and Sequential Art, refers broadly to any narrative medium relying on the deliberate arrangement of images and text to convey meaning through temporal progression, encompassing ancient cave paintings, medieval manuscripts, and modern comics alike.[15] Graphic novels represent a specialized subset of sequential art, characterized by extended page counts—often exceeding 100 pages—and sophisticated integration of visual sequencing with novelistic plotting, as Eisner himself pioneered with A Contract with God in 1978 to transcend the perceived limitations of "comics" as juvenile or fragmentary entertainment.[16] Thus, while all graphic novels employ sequential art principles, the form elevates them through sustained narrative depth and production as cohesive artifacts, distinguishing them from shorter or more utilitarian applications of the medium.[17]Historical Development

Precursors in Sequential Art (Pre-20th Century)

Sequential art, the arrangement of pictorial elements to convey narrative progression over time, appeared in ancient civilizations as a means to document historical, mythological, or daily events. The Narmer Palette, an Egyptian artifact from circa 3100 BCE, features carved scenes on both sides depicting the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt under King Narmer, marking an early instance of juxtaposed images implying sequence.[18] In Rome, Trajan's Column, erected in 113 CE, spirals with a continuous frieze of over 2,500 figures across 155 scenes chronicling Emperor Trajan's Dacian campaigns, read from bottom to top in chronological order to narrate military victories and logistics.[19] Medieval Europe produced notable examples in embroidered and manuscript forms. The Bayeux Tapestry, an embroidered linen cloth approximately 70 meters long created around 1070–1080 CE, illustrates the Norman Conquest of England in 50 sequential panels, from King Edward's death to William the Conqueror's coronation, with Latin inscriptions aiding the visual flow.[20] This work exemplifies continuous narrative, where figures recur across scenes to link events without strict panel borders.[21] In East Asia, Japanese emakimono—horizontal handscrolls like the 12th-century Chōjū-giga (Scrolls of Frolicking Animals)—unfold sequentially to depict anthropomorphic tales and Buddhist parables, blending text and illustration in a manner akin to later comics.[22] The 18th century saw printed sequential engravings emerge as satirical moral tales in Europe. English painter and engraver William Hogarth pioneered this with A Harlot's Progress (1732), a series of six copperplate engravings tracing a young woman's descent from rural innocence to London vice and death, sold as affordable sets to critique social ills.[23] Hogarth's A Rake's Progress (1735), another eight-plate sequence, similarly follows a profligate heir's ruin, using exaggerated figures and symbolic details to advance the story across images without dialogue balloons.[24] These works prioritized causal progression through visual cause-and-effect, influencing print culture by demonstrating narrative potential in reproducible series.[25] By the 19th century, bound volumes integrated text and caricature more fluidly. Swiss educator Rodolphe Töpffer, often credited as the originator of the modern comic strip, privately circulated Histoire de M. Vieux Bois in 1827 and published it in 1837, featuring 30-40 loose drawings per story of absurd protagonists in picaresque adventures, with captions below panels.[26] Töpffer's techniques—irregular panel layouts, dynamic scribbled lines, and text-image interdependence—anticipated graphic novels, as seen in his Essai sur la physionomie (1845), where he theorized visual storytelling's rhetorical power.[27] These precursors, while lacking the sustained novel-length scope of later graphic novels, established sequential art's capacity for extended, autonomous narratives unbound by text primacy.[28]Foundations in Early 20th-Century Comics (1920s-1960s)

The comic book format emerged in the early 1930s as an evolution from newspaper strips, providing a bound medium for sequential art that supported extended narratives beyond daily or Sunday installments. Parallel to this transition, other prototypical experiments in long-form comics appeared, such as American cartoonist Milt Gross’s He Done Her Wrong (1930), a wordless comic published as a hardcover book, which demonstrated the narrative potential of extended sequential art outside the newspaper format.[29] In 1933, Eastern Color Printing Company produced Funnies on Parade, a promotional giveaway reprinting popular strips like Mutt and Jeff and Joe Palooka in tabloid size, which tested market demand and led to the first ongoing commercial comic book, Famous Funnies, launched in 1934 by the same publisher at 10 cents per issue.[30] These initial publications reprinted syndicated strips but established the staple-bound, 64-page standard that allowed for serialized continuity, laying groundwork for original long-form storytelling. Early comic books typically employed an anthology format, featuring multiple serialized stories or reprinted strips per issue, to distinguish from later single-narrative graphic novels.[31] The late 1930s ushered in the Golden Age of Comics with the debut of superheroes, transforming the medium into a vehicle for mythic, episodic adventures. Action Comics #1 in June 1938 introduced Superman, created by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster for National Allied Publications (later DC Comics), selling approximately 200,000 copies initially and sparking a superhero boom amid the Great Depression's escapism demand.[32] This success prompted competitors like Timely Comics (later Marvel) to launch titles such as Marvel Comics #1 in 1939, featuring Human Torch and Namor, while Fawcett Comics' Captain Marvel debuted in Whiz Comics #2 the same year, achieving peak circulations exceeding 1 million copies per issue by the mid-1940s.[33] Industry-wide, comic book sales climbed from under 5 million units annually in 1938 to tens of millions monthly by 1941, fueled by newsstand distribution and affordable pricing.[33] World War II accelerated comics' cultural role, with over 200 million copies printed yearly by 1943 for military distribution and homefront morale, often featuring patriotic heroes combating Axis powers.[32] Postwar diversification into horror, crime, and romance genres—exemplified by Entertaining Comics (EC)'s Tales from the Crypt (1950)—pushed boundaries with graphic depictions, achieving sales of 1-2 million per title before backlash.[34] Psychiatrist Fredric Wertham's 1954 book Seduction of the Innocent attributed rising juvenile delinquency to such content, including criticisms of romance comics for portraying female characters with exaggerated secondary sexual characteristics such as accentuated breasts and hips to appeal to adolescent readers and foster premature sexual interest; citing anecdotal evidence from his clinic patients, although he publicly opposed formal government censorship, he advocated for restrictions on violent and sexual content in comics to protect children, influencing 1954 Senate subcommittee hearings led by Estes Kefauver.[34][35][36] In October 1954, publishers adopted the Comics Code Authority (CCA), a voluntary self-regulatory seal prohibiting "excessive" violence, undead monsters, and suggestive themes, which halted EC's horror line, prompted romance publishers to self-censor controversial material in favor of narratives emphasizing conventional gender roles, love, and marriage, and shifted overall focus to sanitized superheroes; these changes contributed to the decline of the romance genre amid evolving cultural attitudes including the sexual revolution, while reducing industry sales by an estimated 20-30% in the late 1950s.[37][38][39] From the 1940s and 1950s, various works anticipated the graphic novel concept through single-story or long-form narrative structures, including picture novels and extended stories in book format. The Classics Illustrated series disseminated adaptations of classic novels into comic format.[40] In 1946, Citizen 13660 by Miné Okubo offered an illustrated narrative on the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.[41] Also in 1946, the Italian publisher Editore Ventura released comic collections presented as "romanzo completo" (complete novel) and "interamente illustrato a quadretti" (entirely illustrated in panels), using the term "Picture Novel" on the covers of their bilingual Italian-English magazine Per voi! For you!.[42] In 1947, Fawcett Comics issued Comics Novel #1: Anarcho, Dictator of Death, a 52-page comic devoted to one story.[43] In 1948, the Spanish publisher Ediciones Reguera launched the collection La novela gráfica, adapting major world literature novels into illustrated formats aimed at adults, with its announcement stating: "La Novela Gráfica os dará a conocer las mejores novelas de la literatura mundial por medio de dibujos explicados. Cada número contendrá el argumento completo de una novela de amor, aventura, pasión o intriga, siempre dirigida al público adulto. Se publicarán dos números mensuales."[44] St. John Publications released picture novels such as It Rhymes with Lust (1950), an adult-oriented work with film noir influences written by Arnold Drake and Leslie Waller and illustrated by Matt Baker and Ray Osrin, followed by The Case of the Winking Buddha (1950) by Manning Lee Stokes with art by Charles Raab, later republished in Authentic Police #25 (1953).[45][46] Other examples include Mansion of Evil (1950) by Joseph Millard.[47] These works from St. John Publications coexisted with initiatives like Harvey Kurtzman's Jungle Book (1959), which prefigured graphic novel structures with multiple interconnected stories, demonstrating a continuous tradition of extended narratives in comics prior to the widespread adoption of the term "graphic novel". The 1960s initiated the Silver Age, revitalizing comics through character-driven complexity and interconnected universes. Marvel Comics, under editor Martin Goodman and writer-editor Stan Lee, launched The Fantastic Four #1 in November 1961, illustrated by Jack Kirby, introducing relatable, flawed protagonists amid Cold War anxieties, with initial print runs of 300,000 copies that grew steadily.[32] This approach contrasted DC's archetypal heroes, fostering narrative depth via ongoing serialization that prefigured graphic novel collections. Concurrently, underground comix arose in countercultural hubs like San Francisco, with artists like Robert Crumb self-publishing works such as Zap Comix #1 (1968), evading CCA restrictions through alternative distribution and exploring adult themes, thus expanding comics' artistic scope beyond mainstream constraints.[48] These innovations in format, genre experimentation, and thematic ambition provided the sequential and production foundations for later graphic novels, emphasizing sustained visual narratives over ephemeral strips.[32]Pioneering Works and Term Adoption (1970s-1980s)

In 1970, Brazilian publisher Taíka published O Filho de Satã, written by Rubens Francisco Lucchetti and illustrated by Nico Rosso, frequently cited as one of the earliest examples of a graphic novel in Brazil.[49] Gil Kane's Blackmark, illustrated by Kane and scripted by Archie Goodwin, was published in 1971 by Bantam Books as a 92-page paperback blending prose and sequential artwork in a post-apocalyptic sword-and-sorcery narrative following the orphan Blackmark's rise as a warrior.[50] This work, predating widespread use of the term "graphic novel," is frequently cited as an early prototype due to its original, book-format presentation aimed at a broader audience beyond periodical comics, building on the earlier lineage of extended narratives established by publishers like St. John Publications and differentiating itself through consolidation of the format in the mass market.[16] Burne Hogarth's adaptations of Tarzan of the Apes (1972) and Jungle Tales of Tarzan (1976), published by Watson-Guptill, represent additional early standalone graphic novels featuring sequential artwork alongside Edgar Rice Burroughs' original text in book format.[51][52] Sanho Kim's The Sword and the Maiden, volume 1 of Sword’s Edge, published in 1973 by Iron Horse Publishing in the US, represents another early standalone graphic novel with a fantasy adventure narrative, similar to Blackmark in its intent for book-format distribution beyond periodicals.[53][54] In 1978, two landmark publications advanced the format's recognition. Don McGregor and Paul Gulacy's Sabre: Slow Fade of an Endangered Species, a 48-page creator-owned story of a black freedom fighter in a dystopian corporate wasteland, was released by Eclipse Enterprises and distributed through bookstores, earning acclaim as one of the first modern graphic novels for its mature themes and cinematic style.[55] [56] Concurrently, Will Eisner's A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories appeared from Baronet Publishing, comprising four interconnected tales of immigrant life in 1930s Bronx tenements, which Eisner marketed as a "graphic novel" to emphasize its novelistic depth and semi-autobiographical seriousness, distancing it from the perceived juvenility of mainstream comics.[6] [57] In France, publishers innovated during this period with soft covers, black-and-white printing, unusual formats, and departures from the standard 50-page hardcover album structure. Casterman launched the collection "les romans (À suivre)". A notable example is Ici Même, a black-and-white graphic novel of 163 pages across eleven chapters, scripted by Jean-Claude Forest and illustrated by Jacques Tardi, which was pre-published in the (À suivre) magazine in 1978 and released in book form by Casterman in 1979.[58][59] Eisner's deliberate adoption of "graphic novel" in 1978, reportedly to persuade his publisher of the project's literary merit, catalyzed the term's uptake in the industry, though isolated prior uses existed; by the early 1980s, publishers like Marvel launched dedicated graphic novel lines, solidifying its application to standalone, extended narratives.[60] [61] These efforts reflected creators' aims to legitimize sequential art for adult readers, leveraging book trade channels amid comics' underground and direct market shifts.[16]Expansion and Diversification (1990s-Present)

The 1990s marked a period of increasing legitimacy for graphic novels, bolstered by Art Spiegelman's Maus receiving a special Pulitzer Prize citation in 1992 for its Holocaust narrative.[62] DC Comics' Vertigo imprint advanced mature-themed works, including Neil Gaiman's The Sandman series (collected editions 1989–1996), which integrated mythology, horror, and literary elements.[62] Dark Horse Comics debuted Mike Mignola's Hellboy in 1994, fusing folklore, pulp adventure, and occult themes, while Image Comics began emphasizing creator-owned titles across varied genres by the decade's end.[62] Mainstream media coverage and placement in chain bookstores elevated the format's status beyond niche comic shops.[62] The late 1990s introduced significant international diversification through manga translations, with Tokyopop releasing Sailor Moon in 1997 and Viz Media publishing Pokémon comics in 1998, exposing Western audiences to serialized, right-to-left storytelling and influencing visual dynamics in subsequent works.[63] Publishers adopted manga-inspired formats, such as Tokyopop's 2002 right-to-left standard, accelerating cross-cultural exchange.[63] In the 2000s, graphic novels proliferated in non-superhero genres, including literary fiction like Chris Ware's Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth (2000) and autobiographical memoirs such as Marjane Satrapi's Persepolis (2003), which chronicled Iranian experiences.[63] Alison Bechdel's Fun Home (2006) explored family dynamics and sexuality, earning Time magazine's Book of the Year designation, while Gene Luen Yang's American Born Chinese (2006) addressed immigrant identity and received a National Book Award nomination.[63] Scholastic's Graphix imprint relaunched Jeff Smith's Bone in 2005 for younger readers, signaling expansion into middle-grade fantasy.[63] Commercial expansion accelerated with the Book Industry Study Group's approval of a dedicated graphic novels BISAC category in 2003, facilitating bookstore distribution.[63] Sales of graphic novels reached $330 million by 2006, surpassing periodical comics, and contributed to a total market of $1.28 billion by 2020, driven by librarian advocacy, internet accessibility, and the returnable book format's appeal to trade publishers.[64] From the 2010s onward, diversification encompassed young adult realism (Smile by Raina Telgemeier, 2010), civil rights non-fiction (March trilogy, National Book Award 2016), and digital formats via ComiXology (launched 2007) and Webtoon (global rollout 2014).[63] Children's series like Dav Pilkey's Dog Man (2016) achieved million-copy print runs, while Jerry Craft's New Kid won the Newbery Medal in 2020, underscoring literary integration.[63] This era featured broader genre experimentation in sci-fi, horror, and fantasy, often creator-driven, alongside sustained manga influence on pacing and emotional expressiveness.[64][65]Formal Characteristics

Narrative Structures and Pacing

Graphic novels construct narratives through sequential panels that integrate visual and textual elements, allowing for structures ranging from linear progression to intricate non-linear timelines and interwoven subplots. Panel-to-panel transitions, as theorized by Scott McCloud in his 1993 analysis, form the foundational grammar of this sequencing, with six categories dictating shifts in focus and temporal flow: moment-to-moment transitions, which depict fractional changes to elongate perceived time; action-to-action, linking sequential events within a scene for steady momentum; subject-to-subject, varying perspectives on the same subject to build intimacy; scene-to-scene, bridging disparate locations or moments via reader inference; aspect-to-aspect, evoking contemplative atmospheres through environmental details; and non-sequitur, introducing abrupt disruptions for thematic rupture or surprise.[66][67] These transitions enable graphic novels to mimic cinematic montage while harnessing the reader's active role in "closure"—mentally completing unseen actions in the gutters—thus embedding causality directly into the visual syntax rather than relying solely on descriptive prose.[68] Pacing emerges from the deliberate manipulation of panel density, size, and arrangement, where structural choices dictate rhythmic intensity independent of word count. High panel counts per page, often in grid or irregular layouts, compress time and accelerate tempo, suiting high-stakes action or rapid dialogue exchanges by fragmenting moments into digestible beats that propel forward momentum.[69] Conversely, expansive splash pages or elongated vertical panels decelerate the narrative, granting space for visual contemplation and emotional resonance, as larger formats demand prolonged gaze to parse intricate details or symbolic compositions.[70] Gutters amplify this control: narrow voids imply instantaneous linkage, fostering urgency, while wider expanses evoke elapsed intervals, facilitating non-linear jumps like flashbacks without explicit narration. This dual control over structure and rhythm permits graphic novels to achieve decompression—stretching mundane or introspective sequences across multiple panels for subtle psychological depth—or compression for plot efficiency, adapting prose-derived arcs to visual demands. For example, irregular diagonal panels or overlaps can heighten dramatic tension by directing eye flow akin to dynamic cinematography, while symmetrical grids enforce deliberate, measured progression in expository builds.[71] Such techniques distinguish graphic novels from shorter comics by sustaining long-form coherence, where pacing variances underscore thematic contrasts, as in alternating frenetic battles with serene interludes to mirror character internality. Empirical analysis of reader eye-tracking confirms that these elements guide saccadic patterns, optimizing cognitive engagement over passive text consumption.[72]Visual and Production Elements

Graphic novels employ sequential panel layouts to convey narrative progression, where individual frames bordered by lines enclose illustrations, separated by gutters that imply temporal or spatial transitions.[73] Splash pages, extending across full spreads without borders or with bleeds reaching page edges, heighten dramatic emphasis or establish expansive scenes.[70] These arrangements dictate reading flow, with irregular or overlapping panels accelerating action and grid-like structures fostering steady pacing.[74] Artistic styles in graphic novels range from detailed realism to stylized abstraction, utilizing techniques such as cross-hatching for shading, dynamic line work for motion, and integrated text via speech balloons or captions to synchronize verbal and visual information.[75] Coloring, whether traditional hand-applied or digital, enhances mood and depth, though many early works like Blackmark (1971) favored black-and-white for textual focus and cost efficiency.[76] Production formats typically adopt book-like dimensions, such as 7x10 inches, with perfect binding featuring glued spines for durability over the saddle-stitch stapling common in periodicals.[77] [78] Higher-quality paper stocks and offset printing processes distinguish graphic novel production from newsprint-based comics, enabling finer line reproduction and reduced ink bleed, as seen in pioneering volumes printed on coated stock.[79] Absent advertisements and serialized constraints allow uninterrupted page designs, prioritizing artistic cohesion over commercial interruptions.[80] Digital tools have since streamlined inking and lettering, yet traditional methods persist for authenticity in limited editions.[81]