Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

E9 tuning

View on Wikipedia

E9 tuning is a common tuning for steel guitar necks of more than six strings. It is the most common tuning for the neck located furthest from the player on a two-neck console steel guitar or pedal steel guitar while a C6 neck is the one closer to the player. The E9 is a popular tuning for single neck instruments of eight or more strings. This tuning has evolved in the last half of the twentieth century with input from prominent performers including Jimmy Day, Ralph Mooney and Buddy Emmons to support optimal chord and scale patterns across a single fret on the 10-string pedal steel guitar.

Corresponding tunings for a six string lap steel guitar are the E6 tuning E–G♯–B–C♯–E–G♯, or E7 tuning B–D–E–G♯–B–E.

A popular E9 tuning for eight string console steel guitar is the Western swing tuning E–G♯–B–D–F♯–G♯–B–E, low to high and near to far.

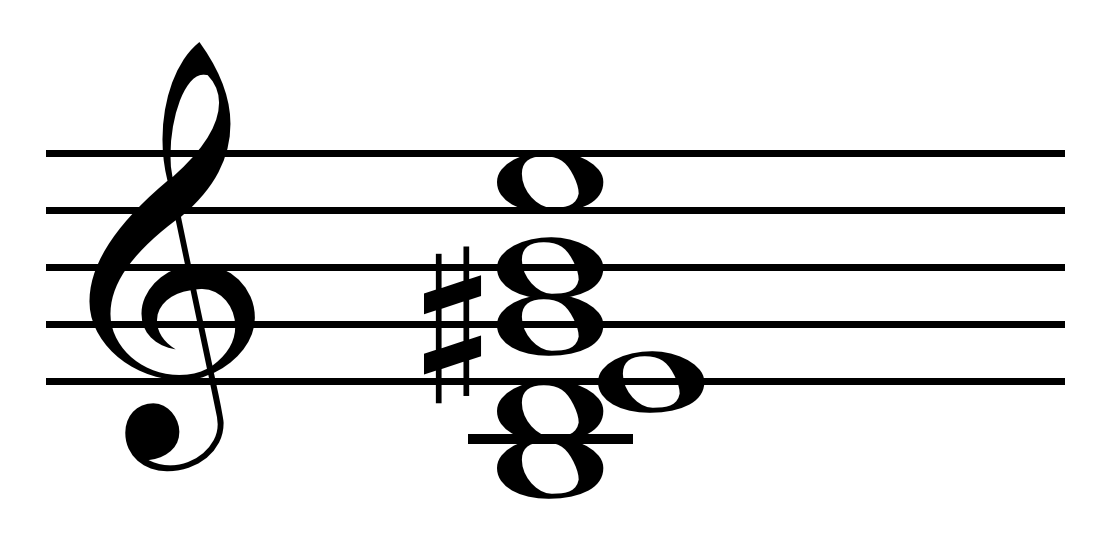

The standard Nashville E9 tuning also called the E9 chromatic tuning[1]: 7 for ten string pedal steel guitar is B–D–E–F♯–G♯–B–E–G♯–D♯–F♯.[2]

History and evolution

[edit]The Nashville standard E9 tuning was developed primarily from 1950 to 1970 during experimentation by elite steel guitarists. Educator Mark Van Allen called the modern E9 tuning "logical" and the "perfect vehicle for most modern music".[3] In 1958, Jimmy Day added an E string (duplicate of the root note) to the middle of the 1940s-style eight-string E9 tuning (E-G♯-B-D-F♯-G♯-B-E) to make nine strings.[4] The change was adopted by other players to become a permanent fixture in the E9 tuning. In 1959, Ralph Mooney added a G♯ (a third interval) at the top end, making ten strings, also an enduring advancement.[4] Buddy Emmons, in 1962 created a reentrant tuning by adding a D♯ (a major seventh) and F♯ (a ninth) at the top.[4] He also eliminated the lowest two strings, still making ten.[4]

Emmons said, "The thought behind the F♯ and D♯ notes was to fill the gap between the G♯ and C♯ pedal note of the E9 tuning"[5] The Nashville standard E9 for decades has remained B–D–E–F♯–G♯–B–E–G♯–D♯–F♯. It allows the performer to play a major scale without moving the bar.[2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Scott, Dewitt (2010). Anthology of Pedal Steel Guitar: E9 Chromatic Tuning. MelBay. ISBN 9781609749460. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ a b Borisoff, Jason (September 27, 2010). "How Pedal Steel Guitar Works". makingmusicmagazine.com. Making Music Magazine. Retrieved September 1, 2017.

- ^ Van Allen, Mark (April 4, 2016). "The Logic of E9". bb.steelguitarforum.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Kurck, Charles (January 3, 2014). "E9 Charts". bb.steelguitarforum.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

- ^ Emmons, Buddy (July 8, 2002). "Who created the E9th tuning, when, and why?". steelguitarforum.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021.