Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

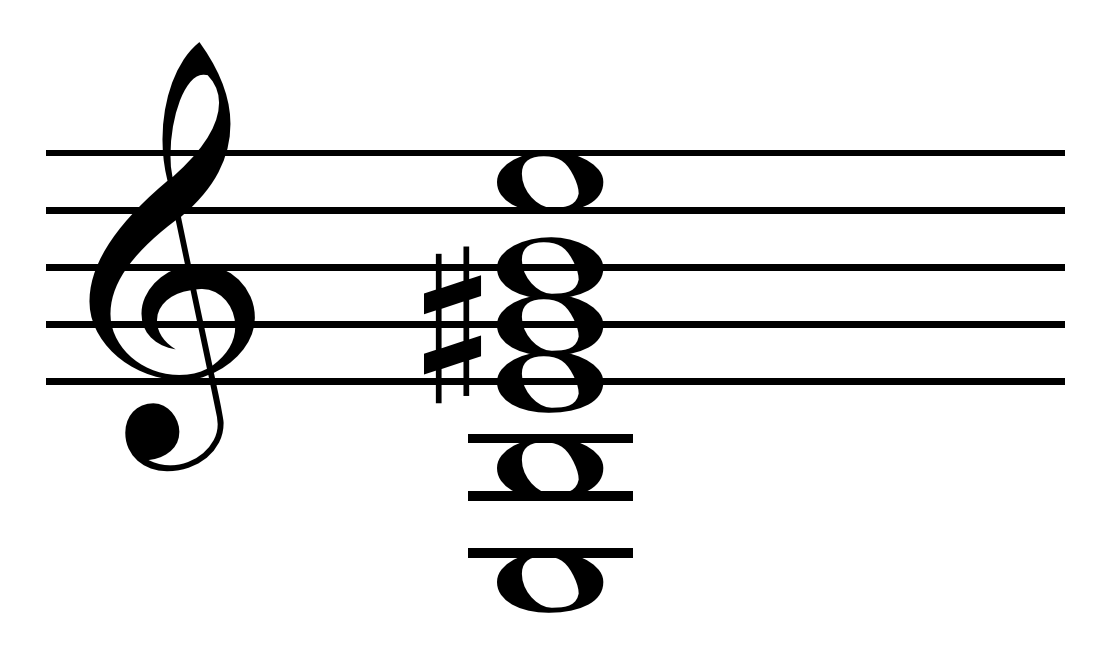

Open E tuning

View on Wikipedia

Open E tuning is a tuning for guitar: low to high, E-B-E-G♯-B-E.[1]

Compared to standard tuning, two strings are two semitones higher and one string is one semitone higher. The intervals are identical to those found in open D tuning. In fact, it is common for players to keep their guitar tuned to open d and place a capo over the second fret. This use of a capo allows for quickly changing between open d and open e without having to manipulate the guitar's tuning pegs.[2]

Familiar examples of open E tuning include the distinctive song "Bo Diddley" by Bo Diddley, the beginning guitar part on the song "Jumpin' Jack Flash" and the rhythm guitar on "Gimme Shelter" by The Rolling Stones, as well as their distinctly earthy blues song "Prodigal Son" from the Beggars Banquet album, originally by Robert Wilkins. The whole of Bob Dylan's Blood on the Tracks album was recorded in open E tuning, although some of the songs were re-recorded in standard tuning prior to the album's release.[3][4] The tuning is also used in The Black Crowes' "She Talks to Angels", Glen Hansard's "Say It To Me Now", Joe Walsh's "Rocky Mountain Way", Rush's "Headlong Flight", Dave Mason's "We Just Disagree", The Faces' "Stay With Me", Billy F. Gibbons in "Just Got Paid", The Smiths' "The Headmaster Ritual",[5] and Hoobastank's "Crawling In The Dark". It is also Derek Trucks' usual open tuning for "Midnight in Harlem" and is used for the guitar on Blink-182's "Feeling This". Open E tuning also lends itself to easy barre-chording as heard in some of these songs. Chris Martin of Coldplay also uses this tuning live in the song "Hurts Like Heaven", but puts a capo on at the sixth fret.

Open E tuning is often used for slide guitar, as it constitutes an open chord, which can be raised by moving the slide further up the neck. Most notably Duane Allman used open E for the majority of his slide work, such as in "Statesboro Blues".

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Open E Tuning on Guitar". www.fender.com. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

- ^ "Open E Tuning: E-B-E-G♯-B-E - Open D Tuning". 2016-08-08. Archived from the original on 2016-08-08. Retrieved 2023-01-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "List of Tunings for Dylan Songs". www.expectingrain.com. Retrieved 2019-08-16.

- ^ "Blood on the Tracks (1975)". dylanchords.com. Retrieved 2025-07-19.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Johnny Marr Teaches "The Headmaster Ritual" by The Smiths | Fender Artist Check-In | Fender". YouTube. 16 April 2020.

Open E tuning

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Basics

Tuning Configuration

Open E tuning on a standard six-string guitar adjusts the pitches of three strings to produce an open E major chord when all strings are strummed without fretting.[1] The specific notes, from the lowest (6th string) to the highest (1st string), are E2, B2, E3, G♯3, B3, and E4.[1][5] To tune from standard EADGBE configuration, retain the 6th string at E2, the 2nd string at B3, and the 1st string at E4; raise the 5th string from A2 to B2 (one whole step); raise the 4th string from D3 to E3 (one whole step); and raise the 3rd string from G3 to G♯3 (one half step).[1][6] These adjustments increase overall string tension, particularly on the 3rd, 4th, and 5th strings, which may require a truss rod adjustment to counteract added neck bow.[1] Heavier string gauges are recommended to balance the elevated tension and ensure comfortable playability; a common set ranges from .013 (high E) to .056 (low E), providing adequate strength for the bass strings without excessive stiffness on the trebles.[7] The following table illustrates the fretboard notes in Open E tuning for the open position and the first four frets, with strings labeled from 6 (lowest) to 1 (highest):| Fret | String 6 | String 5 | String 4 | String 3 | String 2 | String 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | E2 | B2 | E3 | G♯3 | B3 | E4 |

| 1 | F2 | C3 | F3 | A3 | C4 | F4 |

| 2 | F♯2 | C♯3 | F♯3 | A♯3 | C♯4 | F♯4 |

| 3 | G2 | D3 | G3 | B3 | D4 | G4 |

| 4 | G♯2 | D♯3 | G♯3 | C4 | D♯4 | G♯4 |