Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Electromagnetic acoustic transducer

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

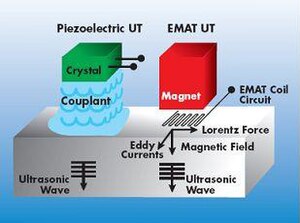

An electromagnetic acoustic transducer (EMAT) is a transducer for non-contact acoustic wave generation and reception in conducting materials. Its effect is based on electromagnetic mechanisms, which do not need direct coupling with the surface of the material. Due to this couplant-free feature, EMATs are particularly useful in harsh, i.e., hot, cold, clean, or dry environments. EMATs are suitable to generate all kinds of waves in metallic and/or magnetostrictive materials. Depending on the design and orientation of coils and magnets, shear horizontal (SH) bulk wave mode (norm-beam or angle-beam), surface wave, plate waves such as SH and Lamb waves, and all sorts of other bulk and guided-wave modes can be excited.[1][2][3] After decades of research and development, EMAT has found its applications in many industries such as primary metal manufacturing and processing, automotive, railroad, pipeline, boiler and pressure vessel industries,[3] in which they are typically used for nondestructive testing (NDT) of metallic structures.

Basic components

[edit]There are two basic components in an EMAT transducer. One is a magnet and the other is an electric coil. The magnet can be a permanent magnet or an electromagnet, which produces a static or a quasi-static magnetic field. In EMAT terminology, this field is called bias magnetic field. The electric coil is driven with an alternating current (AC) electric signal at ultrasonic frequency, typically in the range from 20 kHz to 10 MHz. Based on the application needs, the signal can be a continuous wave, a spike pulse, or a tone-burst signal. The electric coil with AC current also generates an AC magnetic field. When the test material is close to the EMAT, ultrasonic waves are generated in the test material through the interaction of the two magnetic fields.

Transduction mechanism

[edit]There are two mechanisms to generate waves through magnetic field interaction. One is Lorentz force when the material is conductive. The other is magnetostriction when the material is ferromagnetic.

Lorentz force

[edit]The AC current in the electric coil generates eddy current on the surface of the material. According to the theory of electromagnetic induction, the distribution of the eddy current is only at a very thin layer of the material, called skin depth. This depth reduces with the increase of AC frequency, the material conductivity, and permeability. Typically for 1 MHz AC excitation, the skin depth is only a fraction of a millimeter for primary metals like steel, copper and aluminum. The eddy current in the magnetic field experiences Lorentz force. In a microscopic view, the Lorentz force is applied on the electrons in the eddy current. In a macroscopic view, the Lorentz force is applied on the surface region of the material due to the interaction between electrons and atoms. The distribution of Lorentz force is primarily controlled by the design of magnet and design of the electric coil, and is affected by the properties of the test material, the relative position between the transducer and the test part, and the excitation signal for the transducer. The spatial distribution of the Lorentz force determines the precise nature of the elastic disturbances and how they propagate from the source. A majority of successful EMAT applications are based on the Lorentz force mechanism.[4]

Magnetostriction

[edit]A ferromagnetic material will have a dimensional change when an external magnetic field is applied. This effect is called magnetostriction. The flux field of a magnet expands or collapses depending on the arrangement of ferromagnetic material having inducing voltage in a coil and the amount of change is affected by the magnitude and direction of the field.[5] The AC current in the electric coil induces an AC magnetic field and thus produces magnetostriction at ultrasonic frequency in the material. The disturbances caused by magnetostriction then propagate in the material as an ultrasound wave.

In polycrystalline material, the magnetostriction response is very complicated. It is affected by the direction of the bias field, the direction of the field from the AC electric coil, the strength of the bias field, and the amplitude of the AC current. In some cases, one or two peak response may be observed with the increase of bias field. In some cases, the response can be improved significantly with the change of relative direction between the bias magnetic field and the AC magnetic field. Quantitatively, the magnetostriction may be described in a similar mathematical format as piezoelectric constants.[5] Empirically, a lot of experience is needed to fully understand the magnetostriction phenomenon.

The magnetostriction effect has been used to generate both SH-type and Lamb type waves in steel products. Recently, due to the stronger magnetostriction effect in nickel than steel, magnetostriction sensors using nickel patches have been developed for the nondestructive testing of steel products.

Comparison with piezoelectric transducers

[edit]As an ultrasonic testing (UT) method, EMAT has all the advantages of UT compared to other NDT methods. Just like piezoelectric UT probes, EMAT probes can be used in pulse-echo, pitch-catch, and through-transmission configurations. EMAT probes can also be assembled into phased array probes, delivering focusing and beam steering capabilities.[6]

Advantages

[edit]Compared to piezoelectric transducers, EMAT probes have the following advantages:

- No couplant is needed. Based on the transduction mechanism of EMAT, couplant is not required. This makes EMAT ideal for inspections at temperatures below the freezing point and above the evaporation point of liquid couplants. It also makes it convenient for situations where couplant handling would be impractical.

- EMAT is a non-contact method. Although proximity is preferred, a physical contact between the transducer and the specimen under test is not required.

- Dry Inspection. Since no couplant is needed, the EMAT inspection can be performed in a dry environment.

- Less sensitive to surface condition. With contact-based piezoelectric transducers, the test surface has to be machined smoothly to ensure coupling. Using EMAT, the requirements to surface smoothness are less stringent; the only requirement is to remove loose scale and the like.

- Easier for sensor deployment. Using piezoelectric transducer, the wave propagation angle in the test part is affected by Snell's law. As a result, a small variation in sensor deployment may cause a significant change in the refracted angle.

- Easier to generate SH-type waves. Using piezoelectric transducers, SH wave is difficult to couple to the test part. EMAT provide a convenient means of generating SH bulk wave and SH guided waves.

Challenges and disadvantages

[edit]The disadvantages of EMAT compared to piezoelectric UT can be summarised as follows:

- Low transduction efficiency. EMAT transducers typically produce raw signal of lower power than piezoelectric transducers. As a result, more sophisticated signal processing techniques are needed to isolate signal from noise.

- Limited to metallic or magnetic products. NDT of plastic and ceramic material is not suitable or at least not convenient using EMAT.

- Size constraints. Although there are EMAT transducers as small as a penny, commonly used transducers are large in size. Low-profile EMAT problems are still under research and development. Due to the size constraints, EMAT phased array is also difficult to be made from very small elements.

- Caution must be taken when handling magnets around steel products.

Applications

[edit]EMAT has been used in a broad range of applications and has the potential to be used in many others. A brief and incomplete list is as follows.

- Thickness measurement for various applications[7]

- Flaw detection in steel products

- Plate lamination defect inspection

- Bonded structure lamination detection[8][9]

- Laser weld inspection for automotive components

- Weld inspection for coil join, tubes and pipes[10]

- Pipeline in-service inspection[11][12]

- Railroad rail and wheel inspection

- Austenitic weld inspection for the power industry[6]

- Material characterization[13][14]

In addition to the above-mentioned applications, which fall under the category of nondestructive testing, EMATs have been used in research for ultrasonic communication, where they generate and receive an acoustic signal in a metallic structure.[15] Ultrasonic communication is particularly useful in areas where radio frequency can not be used. This includes underwater and underground environments as well as sealed environments, e.g., communication with a sensor inside a pressure tank.

The use of EMATs is also under study for biomedical applications,[16] in particular for electromagnetic acoustic imaging.[17][18]

References

[edit]- ^ R.B. Thompson, Physical Principles of Measurements with EMAT Transducers,Ultrasonic Measurement Methods, Physical Acoustics Vol XIX, Edited by R.N. Thurston and Allan D. Pierce, Academic Press, 1990

- ^ B.W. Maxfield, A. Kuramoto, and J.K. Hulbert, Evaluating EMAT Designs for Selected Applications, Mater. Eval., Vol 45, 1987, p1166

- ^ a b Innerspec Technologies

- ^ B.W. Maxfield and Z. Wang, 2018, Electromagnetic Acoustic Transducers for Nondestructive Evaluation, in ASM Handbook, Volume 17: Nondestructive Evaluation of Materials, ed. A. Ahmad and L. J. Bond, ASM International, Materials Park, OH, pp. 214–237.

- ^ a b Masahiko Hirao and Hirotsugu Ogi, EMATS For Science and Industry, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003

- ^ a b Gao, H., and B. Lopez, "Development of Single-Channel and Phased Array EMATs for Austenitic Weld Inspection", Materials Evaluation (ME), Vol. 68(7), 821-827,(2010).

- ^ M Gori, S Giamboni, E D'Alessio, S Ghia and F Cernuschi, 'EMAT transducers and thickness characterization on aged boiler tubes', Ultrasonics 34 (1996) 339-342.

- ^ S Dixon, C Edwards and S B Palmer, 'The analysis of adhesive bonds using electromagnetic acoustic transducers', Ultrasonics Vol. 32 No. 6, 1994.

- ^ H. Gao, S. M. Ali, and B. Lopez, "Efficient detection of delamination in multilayered structures using ultrasonic guided wave EMATs" in NDT&E International Vol. 43 June 2010, pp: 316-322.

- ^ H. Gao, B. Lopez, S.M. Ali, J. Flora, and J. Monks (Innerspec Technologies), "Inline Testing of ERW Tubes Using Ultrasonic Guided Wave EMATs" in 16th US National Congress of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics (USNCTAM2010-384), State College, PA, USA, June 27-July 2, 2010.

- ^ M Hirao and H Ogi, 'An SH-wave EMAT technique for gas pipeline inspection', NDT&E International 32 (1999) 127-132

- ^ Stéphane Sainson, 'Inspection en ligne des pipelines : principes et méthodes, Ed. Lavoisier 2007'

- ^ H. Ogi, H. Ledbetter, S. Kim, and M. Hirao, "Contactless mode-selective resonance ultrasound spectroscopy: Electromagnetic acoustic resonance," Journal of the ASA, vol. 106, pp. 660-665, 1999.

- ^ M. P. da Cunha and J. W. Jordan, "Improved longitudinal EMAT transducer for elastic constant extraction," in Proc. IEEE Inter. Freq. Contr. Symp, 2005, pp. 426-432.

- ^ X. Huang, J. Saniie, S. Bakhtiari, and A. Heifetz, "Ultrasonic Communication System Design Using Electromagnetic Acoustic Transducer," in 2018 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), 2018, pp. 1–4.

- ^ Liu S, Zhang R, Zheng Z, Zheng Y (2018). "Electromagnetic−Acoustic Sensing for Biomedical Applications". Sensors. 18 (10): 3203. Bibcode:2018Senso..18.3203L. doi:10.3390/s18103203. PMC 6210000. PMID 30248969.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Emerson JF, Chang DB, McNaughton S, Emerson EM, Cerwin SA (2021). "Electromagnetic acoustic imaging methods: resolution, signal-to-noise, and image contrast in phantoms". Journal of Medical Imaging. 8 (6) 067001. doi:10.1117/1.JMI.8.6.067001. PMC 8685282. PMID 34950749.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Boonsang S, Richard J. Dewhurst (March 2014). A highly sensitive laser-EMAT imaging system for biomedical applications. 2014 International Electrical Engineering Congress (iEECON). doi:10.1109/iEECON.2014.6925962.

Codes and standards

[edit]- ASTM E1774-96 Standard Guide for Electromagnetic Acoustic Transducers (EMATs)

- ASTM E1816-96 Standard Practice for Ultrasonic Examinations Using Electromagnetic Acoustic Transducer (EMAT) Technology

- ASTM E1962-98 Standard Test Methods for Ultrasonic Surface Examinations Using Electromagnetic Acoustic Transducer (EMAT) Technology