Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Oxide

View on Wikipedia

An oxide (/ˈɒksaɪd/) is a chemical compound containing at least one oxygen atom and one other element[1] in its chemical formula. "Oxide" itself is the dianion (anion bearing a net charge of −2) of oxygen, an O2− ion with oxygen in the oxidation state of −2. Most of the Earth's crust consists of oxides. Even materials considered pure elements often develop an oxide coating. For example, aluminium foil develops a thin skin of Al2O3 (called a passivation layer) that protects the foil from further oxidation.[2]

Stoichiometry

[edit]Oxides are extraordinarily diverse in terms of stoichiometries (the measurable relationship between reactants and chemical equations of an equation or reaction) and in terms of the structures of each stoichiometry. Most elements form oxides of more than one stoichiometry. A well known example is carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide.[2] This applies to binary oxides, that is, compounds containing only oxide and another element. Far more common than binary oxides are oxides of more complex stoichiometries. Such complexity can arise by the introduction of other cations (a positively charged ion, i.e. one that would be attracted to the cathode in electrolysis) or other anions (a negatively charged ion). Iron silicate, Fe2SiO4, the mineral fayalite, is one of many examples of a ternary oxide. For many metal oxides, the possibilities of polymorphism and nonstoichiometry exist as well.[3] The commercially important dioxides of titanium exists in three distinct structures, for example. Many metal oxides exist in various nonstoichiometric states. Many molecular oxides exist with diverse ligands as well.[4]

For simplicity sake, most of this article focuses on binary oxides.

Formation

[edit]Oxides are associated with all elements except a few noble gases. The pathways for the formation of this diverse family of compounds are correspondingly numerous.

Metal oxides

[edit]Many metal oxides arise by decomposition of other metal compounds, e.g. carbonates, hydroxides, and nitrates. In the making of calcium oxide, calcium carbonate (limestone) breaks down upon heating, releasing carbon dioxide:[2]

- CaCO3 → CaO + CO2

The reaction of elements with oxygen in air is a key step in corrosion relevant to the commercial use of iron especially. Almost all elements form oxides upon heating with oxygen atmosphere. For example, zinc powder will burn in air to give zinc oxide:[5]

- 2 Zn + O2 → 2 ZnO

The production of metals from ores often involves the production of oxides by roasting (heating) metal sulfide minerals in air. In this way, MoS2 (molybdenite) is converted to molybdenum trioxide, the precursor to virtually all molybdenum compounds:[6]

- 2 MoS2 + 7 O2 → 2 MoO3 + 4 SO2

Noble metals (such as gold and platinum) are prized because they resist direct chemical combination with oxygen.[2]

Non-metal oxides

[edit]Important and prevalent nonmetal oxides are carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. These species form upon full or partial oxidation of carbon or hydrocarbons. With a deficiency of oxygen, the monoxide is produced:[2]

- 2 CH4 + 3 O2 → 2 CO + 4 H2O

- 2 C + O2 → 2 CO

With excess oxygen, the dioxide is the product, the pathway proceeds by the intermediacy of carbon monoxide:

- CH4 + 2 O2 → CO2 + 2 H2O

- C + O2 → CO2

Elemental nitrogen (N2) is difficult to convert to oxides, but the combustion of ammonia gives nitric oxide, which further reacts with oxygen:

- 4 NH3 + 5 O2 → 4 NO + 6 H2O

- 2 NO + O2 → 2 NO2

These reactions are practiced in the production of nitric acid, a commodity chemical.[7]

The chemical produced on the largest scale industrially is sulfuric acid. It is produced by the oxidation of sulfur to sulfur dioxide, which is separately oxidized to sulfur trioxide:[8]

- S + O2 → SO2

- 2 SO2 + O2 → 2 SO3

Finally the trioxide is converted to sulfuric acid by a hydration reaction:

- SO3 + H2O → H2SO4

Structure

[edit]Oxides have a range of structures, from individual molecules to polymeric and crystalline structures. At standard conditions, oxides may range from solids to gases. Solid oxides of metals usually have polymeric structures at ambient conditions.[9]

Molecular oxides

[edit]- Some important gaseous oxides

-

Carbon dioxide is the main product of fossil fuel combustion.

-

Carbon monoxide is the product of the incomplete combustion of carbon-based fuels and a precursor to many useful chemicals.

-

Nitrogen dioxide is a problematic pollutant from internal combustion engines.

-

Sulfur dioxide, the principal oxide of sulfur, is emitted from volcanoes.

-

Nitrous oxide ("laughing gas") is a potent greenhouse gas produced by soil bacteria.

Although most metal oxides are crystalline solids, many non-metal oxides are molecules. Examples of molecular oxides are carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. All simple oxides of nitrogen are molecular, e.g., NO, N2O, NO2 and N2O4. Phosphorus pentoxide is a more complex molecular oxide with a deceptive name, the real formula being P4O10. Tetroxides are rare, with a few more common examples being ruthenium tetroxide, osmium tetroxide, and xenon tetroxide.[2]

Reactions

[edit]Reduction

[edit]Reduction of metal oxide to the metal is practiced on a large scale in the production of some metals. Many metal oxides convert to metals simply by heating (thermal decomposition). For example, silver oxide decomposes at 200 °C:[10]

- 2 Ag2O → 4 Ag + O2

Most often, however, metal oxides are reduced by a chemical reagent. A common and cheap reducing agent is carbon in the form of coke. The most prominent example is that of iron ore smelting. Many reactions are involved, but the simplified equation is usually shown as:[2]

- 2 Fe2O3 + 3 C → 4 Fe + 3 CO2

Some metal oxides dissolve in the presence of reducing agents, which can include organic compounds. Reductive dissolution of ferric oxides is integral to geochemical phenomena such as the iron cycle.[11]

Hydrolysis and dissolution

[edit]Because the M–O bonds are typically strong, metal oxides tend to be insoluble in solvents, though they may be attacked by aqueous acids and bases.[2]

Dissolution of oxides often gives oxyanions. Adding aqueous base to P4O10 gives various phosphates. Adding aqueous base to MoO3 gives polyoxometalates. Oxycations are rarer, some examples being nitrosonium (NO+), vanadyl (VO2+), and uranyl (UO2+2). Many compounds are known with both oxides and other groups. In organic chemistry, these include ketones and many related carbonyl compounds. For the transition metals, many oxo complexes are known as well as oxyhalides.[2]

Nomenclature and formulas

[edit]The chemical formulas of the oxides of the chemical elements in their highest oxidation state are predictable and are derived from the number of valence electrons for that element. Even the chemical formula of O4, tetraoxygen, is predictable as a group 16 element. One exception is copper, for which the highest oxidation state oxide is copper(II) oxide and not copper(I) oxide. Another exception is fluoride, which does not exist as one might expect—as F2O7—but as OF2.[12]

See also

[edit]- Other oxygen ions: ozonide (O−3), superoxide (O−2), peroxide (O2−2) and dioxygenyl (O+2).

- Suboxide

- Oxohalide

- Oxyanion

- Complex oxide

- See Template:Oxides for a list of oxides.

- Salt

- Wet electrons

References

[edit]- ^ Hein, Morris; Arena, Susan (2006). Foundations of College Chemistry (12th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-74153-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Greenwood, N. N.; & Earnshaw, A. (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd Edn.), Oxford:Butterworth-Heinemann. ISBN 0-7506-3365-4.

- ^ C. N. R. Rao, B. Raveau (1995). Transition Metal Oxides. New York: VCH. ISBN 1-56081-647-3.

- ^ Roesky, Herbert W.; Haiduc, Ionel; Hosmane, Narayan S. (2003). "Organometallic Oxides of Main Group and Transition Elements Downsizing Inorganic Solids to Small Molecular Fragments". Chem. Rev. 103 (7): 2579–2596. doi:10.1021/cr020376q. PMID 12848580.

- ^ Graf, Günter G. (2000). "Zinc". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a28_509. ISBN 3-527-30673-0.

- ^ Roger F. Sebenik; et al. (2005). "Molybdenum and Molybdenum Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_655. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Thiemann, Michael; Scheibler, Erich; Wiegand, Karl Wilhelm (2000). "Nitric Acid, Nitrous Acid, and Nitrogen Oxides". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a17_293. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Müller, Hermann (2000). "Sulfuric Acid and Sulfur Trioxide". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a25_635. ISBN 3527306730.

- ^ P.A. Cox (2010). Transition Metal Oxides. An Introduction to Their Electronic Structure and Properties. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-958894-7.

- ^ "Silver oxide".

- ^ Cornell, R. M.; Schwertmann, U. (2003). The Iron Oxides: Structure, Properties, Reactions, Occurrences and Uses, Second Edition. p. 323. doi:10.1002/3527602097. ISBN 978-3-527-30274-1.

- ^ Schultz, Emeric (2005). "Fully Exploiting the Potential of the Periodic Table through Pattern Recognition". J. Chem. Educ. 82 (11): 1649. Bibcode:2005JChEd..82.1649S. doi:10.1021/ed082p1649.

Oxide

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Classification

Definition

An oxide is a binary chemical compound composed of oxygen and one other chemical element, formed typically through the reaction of that element with oxygen gas. These compounds are central to inorganic chemistry and include examples such as water (H₂O), carbon dioxide (CO₂), and calcium oxide (CaO).[1] Oxides are ubiquitous in nature, with oxygen accounting for about 46% of the Earth's crust by weight, predominantly bound in oxide minerals like silicates and oxides of metals such as iron and aluminum. They form essential components of geological minerals, contribute to atmospheric constituents like carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide, and play critical roles in biological systems through compounds involved in respiration, photosynthesis, and cellular processes.[5] Oxides are distinguished from related oxygen-containing compounds by the oxidation state of oxygen, which is typically -2 in oxides (as O²⁻), whereas peroxides feature an O-O single bond with oxygen in the -1 state (O₂²⁻), and superoxides contain the O₂⁻ ion with oxygen also at -1 but in a different bonding configuration.[6] The term "oxide" originated in the late 18th century, coined by French chemists Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau and Antoine Lavoisier around 1790, blending "oxygène" (oxygen) with the suffix "-ide" from "acide" (acid) to denote compounds of oxygen with other elements.[7]Types of Oxides

Oxides are classified in various ways, primarily based on the elemental composition and their chemical reactivity. This categorization helps in understanding their roles in chemical reactions and applications.Classification by Composition

Metal oxides are binary compounds formed between metals and oxygen, typically exhibiting ionic bonding and solid states at room temperature; they often display basic properties due to the electropositive nature of metals. A representative example is sodium oxide (Na₂O), which reacts vigorously with water to form sodium hydroxide.[1] Non-metal oxides, in contrast, involve non-metals and oxygen, resulting in covalent bonds and frequently gaseous or volatile forms with acidic tendencies. Carbon dioxide (CO₂) serves as a classic example, dissolving in water to produce carbonic acid. Metalloid oxides bridge these categories, showing variable bonding and reactivity; silicon dioxide (SiO₂), for instance, forms a network covalent structure and behaves as an acidic oxide, resisting basic attack but reacting slowly with strong bases like sodium hydroxide.[1][8]Classification by Acid-Base Properties

Oxides are further categorized according to their behavior in acid-base reactions, reflecting their ability to donate or accept protons or electrons. Basic oxides, predominantly from metals in low oxidation states, react with acids to yield salts and water; calcium oxide (CaO), known as quicklime, exemplifies this by neutralizing hydrochloric acid to form calcium chloride. Acidic oxides, usually from non-metals, combine with water or bases to generate acids; sulfur trioxide (SO₃) reacts with water to produce sulfuric acid, a key industrial process. Amphoteric oxides exhibit dual reactivity, interacting with both acids and bases, which is common in oxides of metals near the metalloid boundary; aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃) dissolves in acids to form aluminum salts and in bases to yield aluminates. Neutral oxides lack significant acid-base reactivity and are often from elements like carbon or nitrogen; carbon monoxide (CO) does not react with acids or bases under standard conditions. Representative examples of these classifications include:- Basic oxides: Na₂O, CaO, MgO, Fe₂O₃, Fe₃O₄ (Fe₃O₄ is a mixed-valence oxide but exhibits predominantly basic behavior)

- Acidic oxides: CO₂, SO₃, P₂O₅, SiO₂ (SiO₂ forms network structures and shows acidic character despite low reactivity with most acids except HF)

- Amphoteric oxides: Al₂O₃, ZnO, PbO

- Neutral oxides: CO, NO, N₂O

Mixed and Complex Oxides

Mixed oxides incorporate multiple metal cations or behave as combinations of simpler oxides, leading to unique properties like enhanced stability or catalytic activity. Magnetite (Fe₃O₄) is a well-known mixed oxide, effectively a composite of iron(II) oxide (FeO) and iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃), used in magnetic applications. Complex oxides feature intricate structures with multiple cations arranged in specific lattices; spinels, with the formula AB₂O₄ where A and B are divalent and trivalent metals respectively, represent this class, as seen in magnesium aluminate (MgAl₂O₄), which adopts a cubic close-packed oxygen framework with cations in tetrahedral and octahedral sites. These structures often arise in naturally occurring minerals and synthetic materials for electronics and ceramics.[1][10]Rare Types: Suboxides and Mixed-Valence Oxides

Suboxides are uncommon oxides where the oxygen content is deficient relative to the stoichiometric ratio, often resulting in non-stoichiometric compositions and metallic properties; wüstite (nominally FeO but actually Fe_{1-x}O) illustrates this, featuring iron vacancies that impart semiconducting behavior. Mixed-valence oxides contain the same metal ion in more than one oxidation state within the crystal lattice, enabling electron delocalization and interesting electronic properties; lead tetroxide (Pb₃O₄), or red lead, contains both Pb²⁺ and Pb⁴⁺, functioning as a mixture of PbO and PbO₂ and used historically in paints and batteries. These types are less prevalent but significant in advanced materials like catalysts and energy storage devices.[11]Stoichiometry and Nomenclature

Stoichiometric Variations

Oxides frequently exhibit ideal stoichiometry, where the ratio of metal atoms to oxygen atoms follows simple integer proportions determined by the oxidation state of the metal. For instance, magnesium oxide adopts a 1:1 ratio in the formula MgO, reflecting the +2 oxidation state of magnesium.[12] Similarly, iron(III) oxide has a 2:3 ratio in Fe2O3, corresponding to the +3 oxidation state of iron.[13] For metals in the +3 oxidation state, such as aluminum, the typical stoichiometry is M2O3, as seen in Al2O3.[14] In contrast, non-stoichiometric oxides deviate from these integer ratios, often due to intrinsic defect structures such as cation vacancies or interstitial oxygen atoms. A prominent example is wüstite, formulated as Fe1-xO, where x typically ranges from 0.05 to 0.16, arising primarily from iron vacancy defects that maintain charge balance through higher-valence iron ions.[15] This non-stoichiometry is particularly common in transition metal oxides, where structural imperfections allow for compositional flexibility without altering the overall crystal lattice significantly.[16] The degree of stoichiometry in oxides is influenced by external conditions and intrinsic properties of the elements involved. Temperature plays a key role, as higher temperatures can promote defect formation or annealing, altering the oxygen-to-metal ratio; for example, in nickel oxide, heating reduces defects to approach stoichiometry.[17] Oxygen partial pressure affects the equilibrium composition, with higher pressures favoring oxygen incorporation and lower pressures leading to metal excess, as observed in wüstite where defect concentration varies directly with oxygen activity.[15] Additionally, the variable oxidation states of transition metals enable multiple stable stoichiometries, such as the coexistence of FeO-like and Fe2O3-like phases under different conditions.[14] Non-stoichiometry can be generally illustrated by the formula MxOy, where the ratio x/y is not an integer, reflecting the presence of defects that disrupt perfect periodicity.[18]Naming Conventions

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) recommends systematic nomenclature for oxides, particularly binary compounds, where the name consists of the electropositive element followed by "oxide," with multiplicative prefixes such as "di-" or "tri-" used to denote stoichiometry when necessary.[19] For metals exhibiting variable oxidation states, the oxidation number is indicated in Roman numerals in parentheses after the element name, ensuring clarity; for example, FeO is named iron(II) oxide, while Fe₂O₃ is iron(III) oxide.[19] This stock system is preferred in modern chemical literature to avoid ambiguity.[20] Traditional names, retained for some common oxides, employ Latin-derived roots with suffixes "-ous" for the lower oxidation state and "-ic" for the higher; for instance, Cu₂O is cuprous oxide (copper(I)), and CuO is cupric oxide (copper(II)). Although these are accepted where unambiguous, IUPAC encourages the systematic approach for consistency across compounds.[19] Special cases deviate from standard binary naming to reflect distinct oxygen bonding or stoichiometry. Peroxides, containing the O₂²⁻ ion, are named with the "peroxide" suffix, as in hydrogen peroxide for H₂O₂ or sodium peroxide for Na₂O₂. Superoxides, containing the O₂⁻ ion, are named with the "superoxide" suffix, as in potassium superoxide for KO₂. Ozonides, featuring the O₃⁻ ion, use the "ozonide" ending, exemplified by potassium ozonide (KO₃). Suboxides, with oxygen content below typical stoichiometry, incorporate a "suboxide" descriptor, such as carbon suboxide for C₃O₂.[19] Oxide formulas are typically empirical for ionic compounds (e.g., CuO for cupric oxide) but molecular for covalent ones (e.g., CO₂ for carbon dioxide), reflecting the simplest whole-number ratio versus the actual atomic composition.[19] In complex oxides involving multiple metals or polyatomic components, names combine cation elements with "oxide" and prefixes for stoichiometry, such as calcium titanium oxide for CaTiO₃ (or more precisely, calcium titanium trioxide), where polyatomic oxo-groups are implied in additive nomenclature if coordination is specified.[19]Formation and Preparation

Metal Oxides

Metal oxides are commonly synthesized through direct oxidation, where metals are burned in an oxygen atmosphere to form the corresponding oxides. This method is particularly effective for alkali and alkaline earth metals due to their high reactivity. For instance, lithium metal reacts vigorously with oxygen to produce lithium oxide, as described by the balanced equation: This reaction occurs upon ignition and results in a white solid product, highlighting the exothermic nature of direct oxidation processes for less stable metals.[21] Thermal decomposition represents another key high-temperature approach for preparing metal oxides, often applied to precursors like carbonates or hydroxides. In this process, the precursor is heated to drive off volatile components, leaving behind the oxide. A classic example is the calcination of calcium carbonate to produce quicklime (calcium oxide), which decomposes at around 900°C according to: This endothermic reaction is widely used in lime production and requires controlled heating to achieve complete decomposition without sintering the product excessively. Similar decompositions apply to metal hydroxides, such as magnesium hydroxide yielding magnesia.[22] On an industrial scale, calcination is integral to ceramic production, as seen in the Bayer process for extracting alumina from bauxite. Bauxite ore is digested in sodium hydroxide solution to form sodium aluminate, which is then precipitated as aluminum hydroxide and calcined at temperatures exceeding 1000°C to yield pure alumina (Al₂O₃). This high-temperature step removes water and impurities, producing a fine white powder essential for aluminum smelting and refractories.[23] Specific high-temperature methods are employed for refractory metal oxides, exemplified by the production of zirconia (ZrO₂) from zircon sand (ZrSiO₄). Thermal dissociation or plasma processes decompose zircon at temperatures above 1800°C, liberating silica and forming zirconia via: This yields a stable, high-melting-point oxide used in ceramics and thermal barrier coatings, underscoring the emphasis on elevated temperatures to overcome the stability of silicate precursors.[24]Non-Metal Oxides

Non-metal oxides are primarily prepared through direct reactions between non-metals and oxygen, often involving combustion processes that yield gaseous or volatile products. These methods contrast with those for metal oxides by emphasizing high-temperature combination reactions that produce molecular species rather than extended solids. Combustion of non-metals in oxygen is a common route, where the element is ignited in air or pure oxygen to form the oxide, with the completeness of the reaction depending on oxygen availability and temperature.[25] A representative example is the combustion of carbon, which produces carbon dioxide under complete oxidation conditions according to the reaction: Incomplete combustion, such as in limited oxygen environments, yields carbon monoxide instead: These reactions release significant heat and are fundamental to understanding fuel oxidation, though they are exothermic and self-sustaining once initiated.[26][27] Similarly, sulfur reacts with oxygen upon burning to form sulfur dioxide, typically requiring elevated temperatures to ensure efficient combination: This reaction occurs readily when sulfur is ignited in air, producing a characteristic blue flame and dense fumes of SO₂ gas, which is a key step in sulfur-based industrial chemistry.[28] In laboratory settings, non-metal oxides like dinitrogen pentoxide (N₂O₅) are prepared via dehydration of the corresponding acids using dehydrating agents such as phosphorus pentoxide (P₄O₁₀). For instance, concentrated nitric acid is dehydrated at low temperatures: This method yields N₂O₅ as a white, unstable solid that decomposes readily, highlighting the volatility and reactivity of many non-metal oxides. The process must be controlled to avoid explosive decomposition, and it remains a standard preparative technique for anhydrides of oxyacids.[29] On an industrial scale, the production of sulfur trioxide (SO₃) exemplifies catalytic methods in the contact process for sulfuric acid manufacturing. Sulfur dioxide, obtained from burning sulfur or roasting sulfide ores, is oxidized with oxygen over a vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅) catalyst at approximately 400–450°C and 1–2 atm pressure: The V₂O₅ catalyst, often supported on silica and promoted with alkali metal salts, facilitates the reaction by lowering the activation energy through a redox mechanism involving vanadium oxidation states, achieving conversions exceeding 99% in multiple stages to optimize equilibrium yields. This process is highly efficient and accounts for the majority of global sulfuric acid production, underscoring the role of catalysis in scaling non-metal oxide synthesis.[30]Structure and Bonding

Molecular Structures

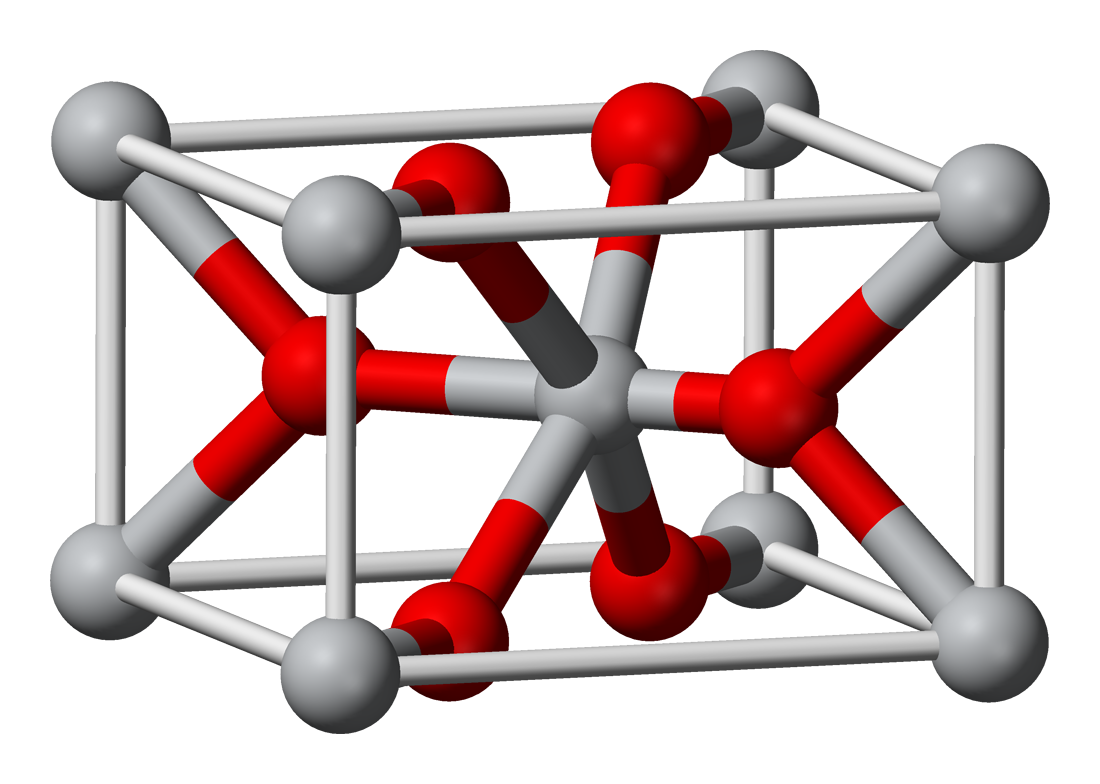

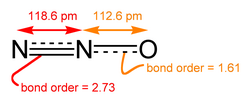

Molecular oxides, particularly those formed by non-metals, exhibit covalent bonding where atoms share electrons to achieve stable electron configurations. In carbon monoxide (CO), the molecule features a triple bond between carbon and oxygen, consisting of one sigma and two pi bonds, resulting in a linear geometry./09:_Covalent_Bonding/9.08:_Coordinate_Covalent_Bond) Similarly, carbon dioxide (CO₂) displays two double bonds, each comprising one sigma and one pi bond, with the central carbon atom undergoing sp hybridization to form the linear structure.[31] This hybridization allows the carbon atom's 2s and one 2p orbital to mix, creating two sp hybrid orbitals that align linearly for optimal bonding.[32] The Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) theory effectively predicts the geometries of these molecular oxides by considering the repulsion between electron pairs around the central atom. For sulfur dioxide (SO₂), the central sulfur atom has three electron domains—two bonding pairs to oxygen and one lone pair—leading to a bent molecular shape with a bond angle of approximately 119 degrees./09:_Molecular_Geometry_and_Covalent_Bonding_Models/9.02:VSEPR-_Molecular_Geometry) In contrast, sulfur trioxide (SO₃) possesses three bonding domains and no lone pairs on the sulfur, resulting in a trigonal planar geometry with bond angles of 120 degrees, facilitated by sp² hybridization of the central atom.[33] Other notable examples include nitrous oxide (N₂O), a linear molecule with the structure or resonance forms, commonly used as an anesthetic gas due to its pharmacological properties.[34] Dichlorine monoxide (Cl₂O) adopts a bent configuration, with the oxygen atom as the central atom bonded to two chlorine atoms and possessing two lone pairs, akin to water's VSEPR classification (AX₂E₂).[35] Spectroscopic techniques such as infrared (IR) and Raman spectroscopy provide evidence for these bond strengths and molecular geometries by identifying characteristic vibrational modes. For instance, the asymmetric stretching mode of CO₂ appears as a strong IR absorption at 2349 cm⁻¹, reflecting the high bond strength of the C=O double bonds, while the symmetric stretch is Raman active but IR inactive due to symmetry.[36] In CO, the C≡O triple bond produces a prominent IR band at 2143 cm⁻¹, indicating its exceptional strength compared to single or double bonds.[37] For SO₂, IR bands around 1362 cm⁻¹ (asymmetric stretch) and 1151 cm⁻¹ (symmetric stretch) confirm the bent structure and varying bond orders influenced by resonance.[38] These vibrational frequencies correlate directly with bond strengths, as higher wavenumbers signify stronger bonds due to greater force constants./4:_Infrared_Spectroscopy/4.1:_Introduction_to_Infrared_Spectroscopy)Crystalline Structures

Many solid-state oxides, especially metal oxides, adopt ionic crystalline lattices where metal cations and oxygen anions are arranged in a regular, three-dimensional array to maximize electrostatic interactions and maintain charge balance. A prominent example is the rock salt (NaCl-type) structure, observed in monovalent oxides like those of alkaline earth metals (e.g., MgO and CaO), featuring a face-centered cubic arrangement of alternating cation and anion layers, with each ion coordinated to six nearest neighbors of the opposite type./06%3A_Structures_and_Energetics_of_Metallic_and_Ionic_solids/6.11%3A_Ionic_Lattices/6.11A%3A_Structure_-Rock_Salt(NaCl)) Sodium oxide (Na₂O), due to its 2:1 cation-to-anion stoichiometry, instead forms an antifluorite lattice, with O²⁻ ions in a face-centered cubic array and Na⁺ ions occupying all tetrahedral interstitial sites, resulting in cubic coordination for oxygen and tetrahedral for sodium.[39] The rutile structure, exemplified by TiO₂, consists of slightly distorted hexagonal close-packed layers of oxide ions with Ti⁴⁺ cations occupying half the octahedral interstices, forming chains of edge-sharing TiO₆ octahedra along the c-axis in a tetragonal unit cell.[40] In contrast, the corundum structure of Al₂O₃ features oxygen anions in a hexagonal close-packed arrangement, with Al³⁺ cations filling two-thirds of the octahedral sites, leading to a trigonal symmetry and strong directional bonding.[41] Non-metal oxides like silica (SiO₂) typically form covalent network structures, where silicon-oxygen bonds create extended three-dimensional frameworks rather than discrete ionic units. Quartz, the most stable polymorph at ambient conditions, comprises corner-sharing SiO₄ tetrahedra arranged in helical chains parallel to the c-axis, with each silicon bonded to four oxygens and each oxygen bridging two silicons, yielding a trigonal lattice with open channels.[42] Cristobalite polymorphs exhibit a more open covalent network, with SiO₄ tetrahedra connected in a diamond-like topology, alternating between cubic (β-cristobalite) and tetragonal (α-cristobalite) forms, resulting in lower density compared to quartz due to larger Si-O-Si bond angles.[42] Defects in ionic oxide lattices play a crucial role in their electrical properties, particularly by enabling ion migration. Schottky defects involve the formation of paired cation and anion vacancies to preserve charge neutrality, as seen in rock salt-type oxides like MgO, where the energy cost is balanced by the lattice's flexibility./Crystal_Lattices/Lattice_Defects/Schottky_Defects) Frenkel defects, conversely, occur when a cation (or sometimes anion) is displaced from its lattice site to an interstitial position, creating a vacancy-interstitial pair; this is prevalent in oxides with significant size disparity between ions, such as ZnO or certain zirconates./Crystal_Lattices/Lattice_Defects/Frenkel_Defects) These intrinsic defects contribute to ionic conductivity by providing pathways for charge carrier diffusion; for instance, in yttria-stabilized zirconia (ZrO₂ doped with Y₂O₃), substitution of Zr⁴⁺ by Y³⁺ generates oxygen vacancies (akin to Schottky-type defects) that facilitate O²⁻ migration, achieving conductivities up to 0.1 S/cm at 1000°C suitable for solid oxide fuel cell electrolytes.[43] Polymorphism in oxides arises from different stable lattice arrangements under varying conditions, influencing stability and reactivity. Titanium dioxide (TiO₂) demonstrates this with its anatase and rutile phases: rutile features tetragonal symmetry with edge-sharing TiO₆ octahedra forming linear chains and a denser packing (density ~4.25 g/cm³), while anatase has body-centered tetragonal symmetry with more distorted octahedra sharing edges and corners in a zigzag pattern, leading to a lower density (~3.89 g/cm³) and higher surface energy.[44] The anatase phase is metastable and transforms to the thermodynamically stable rutile upon heating above ~600°C, a process driven by volume contraction and surface energy minimization.[44]Physical and Chemical Properties

Physical Properties

Oxides exhibit a range of physical states depending on their chemical composition and bonding nature. Most metal oxides are solids at room temperature, characterized by strong ionic or covalent networks that result in high melting points; for example, magnesium oxide (MgO) is a crystalline solid with a melting point of 2825 °C.[45] In contrast, many non-metal oxides exist as gases under standard conditions due to weak intermolecular forces, such as carbon dioxide (CO₂), which has a low sublimation point of -78.5 °C and a density of 1.98 g/L at standard temperature and pressure.[46] Liquid oxides are uncommon at ambient conditions but can occur in molten forms at elevated temperatures, particularly in silicate-based glasses where network structures allow fluidity upon heating.[47] Density and hardness vary significantly between ionic and molecular oxides, reflecting differences in atomic packing and bond strength. Ionic metal oxides, such as MgO, typically display high densities around 3.58 g/cm³ and moderate to high hardness, with MgO registering 5.5–6.0 on the Mohs scale due to its rock-salt crystal structure.[45] Covalent network oxides like silicon dioxide (SiO₂) in quartz form also exhibit substantial density (2.65 g/cm³)[48] and exceptional hardness (Mohs 7)[49], approaching that of diamond in some polymorphs, which contributes to their use in abrasives. Molecular oxides, however, have lower densities; CO₂ gas, for instance, is only 1.53 times denser than air at standard conditions.[46] Color and optical properties of oxides are influenced by electronic transitions and defects in their structures. Many metal oxides appear white or colorless in pure form, such as zinc oxide (ZnO), a white powder that scatters light effectively due to its wide bandgap. Others display distinct colors from d-d transitions or charge transfer, including black copper(II) oxide (CuO), resulting from its monoclinic crystal lattice absorbing visible light.[50] Transparency is notable in certain oxides like aluminum oxide (Al₂O₃) in its sapphire form, which is colorless and transmits light from the ultraviolet (down to ~150 nm) through the near-infrared (~5 μm) with minimal absorption.[51] Thermal stability is a hallmark of many refractory oxides, enabling applications in high-temperature environments. Thorium dioxide (ThO₂), for example, possesses one of the highest melting points among oxides at 3300 °C (3573 K), attributed to its fluorite structure and strong Th-O bonds that resist thermal decomposition.[52] This stability contrasts with less robust molecular oxides like CO₂, which sublimes readily at low temperatures.[46]Acid-Base Properties

Oxides are classified into acidic, basic, amphoteric, and neutral categories based on their interactions with water, acids, and bases, which reflect their position in the periodic table and bonding characteristics.[1] Metal oxides from the left side of the periodic table tend to exhibit basic properties, while non-metal oxides from the right side are typically acidic, with transitional behavior in the middle.[1] Basic oxides, primarily those of alkali and alkaline earth metals, react with water to form hydroxides that act as bases and also neutralize acids. For example, sodium oxide reacts with water to produce sodium hydroxide:Additionally, calcium oxide, or quicklime, reacts with hydrochloric acid to form calcium chloride and water:

[1] Acidic oxides, commonly formed by non-metals, combine with water to yield acids and react with bases to form salts. Carbon dioxide, for instance, forms carbonic acid upon dissolution in water:

Sulfur trioxide reacts with sodium hydroxide to produce sodium sulfate and water:

[1] Amphoteric oxides display dual behavior, acting as bases toward acids and as acids toward bases, often seen in oxides of metals near the metalloid boundary like aluminum. Aluminum oxide dissolves in hydrochloric acid to form aluminum chloride:

It also reacts with sodium hydroxide to form sodium aluminate:

[1] Neutral oxides do not exhibit significant acid-base reactivity with water, acids, or bases. Examples include nitrous oxide (N₂O) and carbon monoxide (CO), which remain largely unreactive in such contexts.[1]

Reactions

Reduction

Reduction of oxides involves the removal of oxygen to recover the elemental form of the metal or non-metal, a critical process in metallurgy and materials science. This deoxygenation is achieved through various methods, each suited to the stability and reactivity of the oxide. The feasibility of these reductions is governed by thermodynamics, where the standard free energy change (ΔG°) determines whether the reaction proceeds spontaneously under given conditions. Thermal reduction using carbon is a widely employed method for less stable metal oxides, particularly in iron production. In the blast furnace process, iron(III) oxide (Fe₂O₃) reacts with carbon to produce metallic iron and carbon monoxide:This reaction occurs at high temperatures (around 1500–2000°C), where coke serves as the carbon source and reducing agent, facilitated by the hot blast of air that generates CO as an intermediate reductant.[53] The process is exothermic in later stages, contributing to the furnace's heat balance, and has been the cornerstone of steelmaking since the 18th century. For more reactive or less stable oxides, hydrogen gas provides a cleaner reducing agent, avoiding carbon-related impurities. A representative example is the reduction of copper(II) oxide:

This reaction proceeds at moderate temperatures (200–300°C) and is often studied for its mechanistic insights, involving surface adsorption and stepwise oxide phase transformations from CuO to Cu₂O and then to Cu metal. Hydrogen reduction is advantageous in producing high-purity metals and is explored for sustainable alternatives to carbon-based methods.[54][55] Electrochemical reduction enables the extraction of metals from highly stable oxides that resist thermal methods. The Hall-Héroult process, developed in 1886, electrolyzes alumina (Al₂O₃) dissolved in molten cryolite (Na₃AlF₆) at approximately 950°C. At the cathode, aluminum ions are reduced to molten aluminum:

while at the carbon anode, oxygen ions form CO₂ via reaction with the anode: overall simplifying to

(with oxygen combining with carbon). This method consumes significant energy (about 13–15 kWh/kg Al) but is essential for aluminum production, accounting for over 95% of global output.[56] Recent advancements include hydrogen direct reduction (HyDR) processes for iron oxides, which use pure hydrogen instead of carbon to produce direct reduced iron (DRI) with minimal CO₂ emissions. As of 2025, pilot plants and commercial facilities, such as those by HYBRIT and H2 Green Steel, demonstrate feasibility at temperatures around 800–1000°C, supporting the transition to low-carbon steelmaking.[57] The thermodynamic viability of these reductions is visualized using the Ellingham diagram, which plots the standard free energy of formation (ΔG°) for oxide formation reactions against temperature. Lines with steeper negative slopes indicate greater oxide stability; a reductant line (e.g., for C to CO or H₂ to H₂O) must lie below the oxide line for spontaneous reduction. For instance, carbon can reduce iron oxides above ~700°C, but not alumina at practical temperatures, explaining the preference for electrochemical methods in aluminum extraction. This diagram, first constructed by Harold Ellingham in 1944, remains a fundamental tool for predicting reduction processes across metals.[58]

Hydrolysis and Dissolution

Basic metal oxides react with water through hydrolysis to form the corresponding metal hydroxides, which are typically sparingly soluble bases. For example, magnesium oxide undergoes a slow hydrolysis reaction:This process is limited by the low solubility of Mg(OH)₂ and often requires elevated temperatures or prolonged exposure to achieve significant conversion.[59] In contrast, oxides of alkali metals, such as sodium oxide, react more readily and exothermically with water to produce strongly basic solutions of alkali hydroxides.[1] Acidic non-metal oxides hydrolyze vigorously with water to yield oxyacids. Sulfur trioxide, for instance, forms sulfuric acid:

Similarly, phosphorus pentoxide hydrolyzes to phosphoric acid:

These reactions are highly exothermic and proceed rapidly, reflecting the covalent nature and high electronegativity of the non-metals involved.[60][61] Amphoteric oxides, such as zinc oxide, exhibit dual behavior by dissolving in either acidic or basic aqueous solutions. In acidic media, ZnO acts as a base:

In alkaline conditions, it behaves as an acid, forming soluble zincate ions:

This pH-dependent solubility arises from the intermediate electronegativity of zinc, allowing the oxide to coordinate with either H⁺ or OH⁻. Network-forming oxides like silica (SiO₂) are largely insoluble in water and most acids but dissolve slowly in hydrofluoric acid due to the formation of stable fluorosilicates:

The reaction is kinetically hindered and typically requires concentrated HF for practical rates.[62][63] Solubility trends for basic oxides show an increase down a group in the periodic table, driven by decreasing lattice energy and increasing ionic size of the metal cation. In Group 2, for example, the hydroxides derived from oxide hydrolysis—such as Mg(OH)₂, Ca(OH)₂, Sr(OH)₂, and Ba(OH)₂—exhibit progressively higher solubility, with Ba(OH)₂ being the most soluble and producing solutions with pH values approaching 14. Alkali metal oxides (Group 1) generally display even greater solubility than their Group 2 counterparts due to lower charge density.[64][1] The stability of oxides in aqueous environments is highly pH-dependent, as depicted in Pourbaix diagrams, which plot the predominant species (oxide, hydroxide, or dissolved ions) against pH and electrochemical potential. These thermodynamic maps reveal stability regions where oxides persist, such as the passivation zone for aluminum oxide in neutral to basic conditions, and dissolution domains in extreme pH, aiding predictions of corrosion or solubility in varied aqueous media.[65]