Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Wavelet

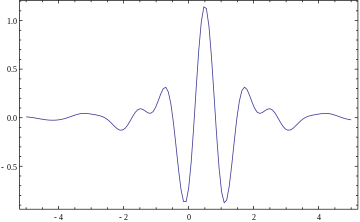

View on WikipediaA wavelet is a wave-like oscillation with an amplitude that begins at zero, increases or decreases, and then returns to zero one or more times. Wavelets are termed a "brief oscillation". A taxonomy of wavelets has been established, based on the number and direction of its pulses. Wavelets are imbued with specific properties that make them useful for signal processing.

For example, a wavelet could be created to have a frequency of middle C and a short duration of roughly one tenth of a second. If this wavelet were to be convolved with a signal created from the recording of a melody, then the resulting signal would be useful for determining when the middle C note appeared in the song. Mathematically, a wavelet correlates with a signal if a portion of the signal is similar. Correlation is at the core of many practical wavelet applications.

As a mathematical tool, wavelets can be used to extract information from many kinds of data, including audio signals and images. Sets of wavelets are needed to analyze data fully. "Complementary" wavelets decompose a signal without gaps or overlaps so that the decomposition process is mathematically reversible. Thus, sets of complementary wavelets are useful in wavelet-based compression/decompression algorithms, where it is desirable to recover the original information with minimal loss.

In formal terms, this representation is a wavelet series representation of a square-integrable function with respect to either a complete, orthonormal set of basis functions, or an overcomplete set or frame of a vector space, for the Hilbert space of square-integrable functions. This is accomplished through coherent states.

In classical physics, the diffraction phenomenon is described by the Huygens–Fresnel principle that treats each point in a propagating wavefront as a collection of individual spherical wavelets.[1] The characteristic bending pattern is most pronounced when a wave from a coherent source (such as a laser) encounters a slit/aperture that is comparable in size to its wavelength. This is due to the addition, or interference, of different points on the wavefront (or, equivalently, each wavelet) that travel by paths of different lengths to the registering surface. Multiple, closely spaced openings (e.g., a diffraction grating), can result in a complex pattern of varying intensity.

Etymology

[edit]The word wavelet has been used for decades in digital signal processing and exploration geophysics.[2] The equivalent French word ondelette meaning "small wave" was used by Jean Morlet and Alex Grossmann in the early 1980s.

Wavelet theory

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2025) |

Wavelet theory is applicable to several subjects. All wavelet transforms may be considered forms of time-frequency representation for continuous-time (analog) signals and so are related to harmonic analysis.[3] Discrete wavelet transform (continuous in time) of a discrete-time (sampled) signal by using discrete-time filterbanks of dyadic (octave band) configuration is a wavelet approximation to that signal. The coefficients of such a filter bank are called the shift and scaling coefficients in wavelets nomenclature. These filterbanks may contain either finite impulse response (FIR) or infinite impulse response (IIR) filters. The wavelets forming a continuous wavelet transform (CWT) are subject to the uncertainty principle of Fourier analysis respective sampling theory:[4] given a signal with some event in it, one cannot assign simultaneously an exact time and frequency response scale to that event. The product of the uncertainties of time and frequency response scale has a lower bound. Thus, in the scaleogram of a continuous wavelet transform of this signal, such an event marks an entire region in the time-scale plane, instead of just one point. Also, discrete wavelet bases may be considered in the context of other forms of the uncertainty principle.[5][6][7][8]

Wavelet transforms are broadly divided into three classes: continuous, discrete and multiresolution-based.

Continuous wavelet transforms (continuous shift and scale parameters)

[edit]In continuous wavelet transforms, a given signal of finite energy is projected on a continuous family of frequency bands (or similar subspaces of the Lp function space L2(R) ). For instance the signal may be represented on every frequency band of the form [f, 2f] for all positive frequencies f > 0. Then, the original signal can be reconstructed by a suitable integration over all the resulting frequency components.

The frequency bands or subspaces (sub-bands) are scaled versions of a subspace at scale 1. This subspace in turn is in most situations generated by the shifts of one generating function ψ in L2(R), the mother wavelet. For the example of the scale one frequency band [1, 2] this function is with the (normalized) sinc function. That, Meyer's, and two other examples of mother wavelets are:

|

|

|

The subspace of scale a or frequency band [1/a, 2/a] is generated by the functions (sometimes called child wavelets) where a is positive and defines the scale and b is any real number and defines the shift. The pair (a, b) defines a point in the right halfplane R+ × R.

The projection of a function x onto the subspace of scale a then has the form with wavelet coefficients

For the analysis of the signal x, one can assemble the wavelet coefficients into a scaleogram of the signal.

See a list of some Continuous wavelets.

Discrete wavelet transforms (discrete shift and scale parameters, continuous in time)

[edit]It is computationally impossible to analyze a signal using all wavelet coefficients, so one may wonder if it is sufficient to pick a discrete subset of the upper halfplane to be able to reconstruct a signal from the corresponding wavelet coefficients. One such system is the affine system for some real parameters a > 1, b > 0. The corresponding discrete subset of the halfplane consists of all the points (am, nb am) with m, n in Z. The corresponding child wavelets are now given as

A sufficient condition for the reconstruction of any signal x of finite energy by the formula is that the functions form an orthonormal basis of L2(R).

Multiresolution based discrete wavelet transforms (continuous in time)

[edit]

In any discretised wavelet transform, there are only a finite number of wavelet coefficients for each bounded rectangular region in the upper halfplane. Still, each coefficient requires the evaluation of an integral. In special situations this numerical complexity can be avoided if the scaled and shifted wavelets form a multiresolution analysis. This means that there has to exist an auxiliary function, the father wavelet φ in L2(R), and that a is an integer. A typical choice is a = 2 and b = 1. The most famous pair of father and mother wavelets is the Daubechies 4-tap wavelet. Note that not every orthonormal discrete wavelet basis can be associated to a multiresolution analysis; for example, the Journe wavelet admits no multiresolution analysis.[9]

From the mother and father wavelets one constructs the subspaces The father wavelet keeps the time domain properties, while the mother wavelets keeps the frequency domain properties.

From these it is required that the sequence forms a multiresolution analysis of L2 and that the subspaces are the orthogonal "differences" of the above sequence, that is, Wm is the orthogonal complement of Vm inside the subspace Vm−1,

In analogy to the sampling theorem one may conclude that the space Vm with sampling distance 2m more or less covers the frequency baseband from 0 to 1/2m-1. As orthogonal complement, Wm roughly covers the band [1/2m−1, 1/2m].

From those inclusions and orthogonality relations, especially , follows the existence of sequences and that satisfy the identities so that and so that The second identity of the first pair is a refinement equation for the father wavelet φ. Both pairs of identities form the basis for the algorithm of the fast wavelet transform.

From the multiresolution analysis derives the orthogonal decomposition of the space L2 as For any signal or function this gives a representation in basis functions of the corresponding subspaces as where the coefficients are and

Time-causal wavelets

[edit]For processing temporal signals in real time, it is essential that the wavelet filters do not access signal values from the future as well as that minimal temporal latencies can be obtained. Time-causal wavelets representations have been developed by Szu et al [10] and Lindeberg,[11] with the latter method also involving a memory-efficient time-recursive implementation.

Mother wavelet

[edit]For practical applications, and for efficiency reasons, one prefers continuously differentiable functions with compact support as mother (prototype) wavelet (functions). However, to satisfy analytical requirements (in the continuous WT) and in general for theoretical reasons, one chooses the wavelet functions from a subspace of the space This is the space of Lebesgue measurable functions that are both absolutely integrable and square integrable in the sense that and

Being in this space ensures that one can formulate the conditions of zero mean and square norm one: is the condition for zero mean, and is the condition for square norm one.

For ψ to be a wavelet for the continuous wavelet transform (see there for exact statement), the mother wavelet must satisfy an admissibility criterion (loosely speaking, a kind of half-differentiability) in order to get a stably invertible transform.

For the discrete wavelet transform, one needs at least the condition that the wavelet series is a representation of the identity in the space L2(R). Most constructions of discrete WT make use of the multiresolution analysis, which defines the wavelet by a scaling function. This scaling function itself is a solution to a functional equation.

In most situations it is useful to restrict ψ to be a continuous function with a higher number M of vanishing moments, i.e. for all integer m < M

The mother wavelet is scaled (or dilated) by a factor of a and translated (or shifted) by a factor of b to give (under Morlet's original formulation):

For the continuous WT, the pair (a,b) varies over the full half-plane R+ × R; for the discrete WT this pair varies over a discrete subset of it, which is also called affine group.

These functions are often incorrectly referred to as the basis functions of the (continuous) transform. In fact, as in the continuous Fourier transform, there is no basis in the continuous wavelet transform. Time-frequency interpretation uses a subtly different formulation (after Delprat).

Restriction:

- when a1 = a and b1 = b,

- has a finite time interval

Comparisons with Fourier transform (continuous-time)

[edit]The wavelet transform is often compared with the Fourier transform, in which signals are represented as a sum of sinusoids. In fact, the Fourier transform can be viewed as a special case of the continuous wavelet transform with the choice of the mother wavelet . The main difference in general is that wavelets are localized in both time and frequency whereas the standard Fourier transform is only localized in frequency. The short-time Fourier transform (STFT) is similar to the wavelet transform, in that it is also time and frequency localized, but there are issues with the frequency/time resolution trade-off.

In particular, assuming a rectangular window region, one may think of the STFT as a transform with a slightly different kernel where can often be written as , where and u respectively denote the length and temporal offset of the windowing function. Using Parseval's theorem, one may define the wavelet's energy as From this, the square of the temporal support of the window offset by time u is given by

and the square of the spectral support of the window acting on a frequency

Multiplication with a rectangular window in the time domain corresponds to convolution with a function in the frequency domain, resulting in spurious ringing artifacts for short/localized temporal windows. With the continuous-time Fourier transform, and this convolution is with a delta function in Fourier space, resulting in the true Fourier transform of the signal . The window function may be some other apodizing filter, such as a Gaussian. The choice of windowing function will affect the approximation error relative to the true Fourier transform.

A given resolution cell's time-bandwidth product may not be exceeded with the STFT. All STFT basis elements maintain a uniform spectral and temporal support for all temporal shifts or offsets, thereby attaining an equal resolution in time for lower and higher frequencies. The resolution is purely determined by the sampling width.

In contrast, the wavelet transform's multiresolutional properties enables large temporal supports for lower frequencies while maintaining short temporal widths for higher frequencies by the scaling properties of the wavelet transform. This property extends conventional time-frequency analysis into time-scale analysis.[12]

The discrete wavelet transform is less computationally complex, taking O(N) time as compared to O(N log N) for the fast Fourier transform (FFT). This computational advantage is not inherent to the transform, but reflects the choice of a logarithmic division of frequency, in contrast to the equally spaced frequency divisions of the FFT which uses the same basis functions as the discrete Fourier transform (DFT).[13] This complexity only applies when the filter size has no relation to the signal size. A wavelet without compact support such as the Shannon wavelet would require O(N2). (For instance, a logarithmic Fourier Transform also exists with O(N) complexity, but the original signal must be sampled logarithmically in time, which is only useful for certain types of signals.[14])

Definition of a wavelet

[edit]A wavelet (or a wavelet family) can be defined in various ways:

Scaling filter

[edit]An orthogonal wavelet is entirely defined by the scaling filter – a low-pass finite impulse response (FIR) filter of length 2N and sum 1. In biorthogonal wavelets, separate decomposition and reconstruction filters are defined.

For analysis with orthogonal wavelets the high pass filter is calculated as the quadrature mirror filter of the low pass, and reconstruction filters are the time reverse of the decomposition filters.

Daubechies and Symlet wavelets can be defined by the scaling filter.

Scaling function

[edit]Wavelets are defined by the wavelet function ψ(t) (i.e. the mother wavelet) and scaling function φ(t) (also called father wavelet) in the time domain.

The wavelet function is in effect a band-pass filter and scaling that for each level halves its bandwidth. This creates the problem that in order to cover the entire spectrum, an infinite number of levels would be required. The scaling function filters the lowest level of the transform and ensures all the spectrum is covered. See[15] for a detailed explanation.

For a wavelet with compact support, φ(t) can be considered finite in length and is equivalent to the scaling filter g.

Meyer wavelets can be defined by scaling functions

Wavelet function

[edit]The wavelet only has a time domain representation as the wavelet function ψ(t).

For instance, Mexican hat wavelets can be defined by a wavelet function. See a list of a few continuous wavelets.

History

[edit]The development of wavelets can be linked to several separate trains of thought, starting with Alfréd Haar's work in the early 20th century. Later work by Dennis Gabor yielded Gabor atoms (1946), which are constructed similarly to wavelets, and applied to similar purposes.

Notable contributions to wavelet theory since then can be attributed to George Zweig's discovery of the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) in 1975 (originally called the cochlear transform and discovered while studying the reaction of the ear to sound),[16] Pierre Goupillaud, Alex Grossmann and Jean Morlet's formulation of what is now known as the CWT (1982), Jan-Olov Strömberg's early work on discrete wavelets (1983), the Le Gall–Tabatabai (LGT) 5/3-taps non-orthogonal filter bank with linear phase (1988),[17][18][19] Ingrid Daubechies' orthogonal wavelets with compact support (1988), Stéphane Mallat's non-orthogonal multiresolution framework (1989), Ali Akansu's binomial QMF (1990), Nathalie Delprat's time-frequency interpretation of the CWT (1991), Newland's harmonic wavelet transform (1993), and set partitioning in hierarchical trees (SPIHT) developed by Amir Said with William A. Pearlman in 1996.[20]

The JPEG 2000 standard was developed from 1997 to 2000 by a Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) committee chaired by Touradj Ebrahimi (later the JPEG president).[21] In contrast to the DCT algorithm used by the original JPEG format, JPEG 2000 instead uses discrete wavelet transform (DWT) algorithms. It uses the CDF 9/7 wavelet transform (developed by Ingrid Daubechies in 1992) for its lossy compression algorithm, and the Le Gall–Tabatabai (LGT) 5/3 discrete-time filter bank (developed by Didier Le Gall and Ali J. Tabatabai in 1988) for its lossless compression algorithm.[22] JPEG 2000 technology, which includes the Motion JPEG 2000 extension, was selected as the video coding standard for digital cinema in 2004.[23]

Timeline

[edit]- First wavelet (Haar's wavelet) by Alfréd Haar (1909)

- Since the 1970s: George Zweig, Jean Morlet, Alex Grossmann

- Since the 1980s: Yves Meyer, Stéphane Mallat, Ingrid Daubechies, Ronald Coifman, Ali Akansu, Victor Wickerhauser

- Since the 1990s: Nathalie Delprat, Newland, Amir Said, William A. Pearlman, Touradj Ebrahimi, JPEG 2000

Wavelet transforms

[edit]A wavelet is a mathematical function used to divide a given function or continuous-time signal into different scale components. Usually one can assign a frequency range to each scale component. Each scale component can then be studied with a resolution that matches its scale. A wavelet transform is the representation of a function by wavelets. The wavelets are scaled and translated copies (known as "daughter wavelets") of a finite-length or fast-decaying oscillating waveform (known as the "mother wavelet"). Wavelet transforms have advantages over traditional Fourier transforms for representing functions that have discontinuities and sharp peaks, and for accurately deconstructing and reconstructing finite, non-periodic and/or non-stationary signals.

Wavelet transforms are classified into discrete wavelet transforms (DWTs) and continuous wavelet transforms (CWTs). Note that both DWT and CWT are continuous-time (analog) transforms. They can be used to represent continuous-time (analog) signals. CWTs operate over every possible scale and translation whereas DWTs use a specific subset of scale and translation values or representation grid.

There are a large number of wavelet transforms each suitable for different applications. For a full list see list of wavelet-related transforms but the common ones are listed below:

- Continuous wavelet transform (CWT)

- Discrete wavelet transform (DWT)

- Fast wavelet transform (FWT)

- Lifting scheme and generalized lifting scheme

- Wavelet packet decomposition (WPD)

- Stationary wavelet transform (SWT)

- Fractional Fourier transform (FRFT)

- Fractional wavelet transform (FRWT)

Generalized transforms

[edit]There are a number of generalized transforms of which the wavelet transform is a special case. For example, Yosef Joseph Segman introduced scale into the Heisenberg group, giving rise to a continuous transform space that is a function of time, scale, and frequency. The CWT is a two-dimensional slice through the resulting 3d time-scale-frequency volume.

Another example of a generalized transform is the chirplet transform in which the CWT is also a two dimensional slice through the chirplet transform.

An important application area for generalized transforms involves systems in which high frequency resolution is crucial. For example, darkfield electron optical transforms intermediate between direct and reciprocal space have been widely used in the harmonic analysis of atom clustering, i.e. in the study of crystals and crystal defects.[24] Now that transmission electron microscopes are capable of providing digital images with picometer-scale information on atomic periodicity in nanostructure of all sorts, the range of pattern recognition[25] and strain[26]/metrology[27] applications for intermediate transforms with high frequency resolution (like brushlets[28] and ridgelets[29]) is growing rapidly.

Fractional wavelet transform (FRWT) is a generalization of the classical wavelet transform in the fractional Fourier transform domains. This transform is capable of providing the time- and fractional-domain information simultaneously and representing signals in the time-fractional-frequency plane.[30]

Applications

[edit]Generally, an approximation to DWT is used for data compression if a signal is already sampled, and the CWT for signal analysis.[31][32] Thus, DWT approximation is commonly used in engineering and computer science,[33] and the CWT in scientific research.[34]

Like some other transforms, wavelet transforms can be used to transform data, then encode the transformed data, resulting in effective compression. For example, JPEG 2000 is an image compression standard that uses biorthogonal wavelets. This means that although the frame is overcomplete, it is a tight frame (see types of frames of a vector space), and the same frame functions (except for conjugation in the case of complex wavelets) are used for both analysis and synthesis, i.e., in both the forward and inverse transform. For details see wavelet compression.

A related use is for smoothing/denoising data based on wavelet coefficient thresholding, also called wavelet shrinkage. By adaptively thresholding the wavelet coefficients that correspond to undesired frequency components smoothing and/or denoising operations can be performed.

Wavelet transforms are also starting to be used for communication applications. Wavelet OFDM is the basic modulation scheme used in HD-PLC (a power line communications technology developed by Panasonic), and in one of the optional modes included in the IEEE 1901 standard. Wavelet OFDM can achieve deeper notches than traditional FFT OFDM, and wavelet OFDM does not require a guard interval (which usually represents significant overhead in FFT OFDM systems).[35]

As a representation of a signal

[edit]Often, signals can be represented well as a sum of sinusoids. However, consider a non-continuous signal with an abrupt discontinuity; this signal can still be represented as a sum of sinusoids, but requires an infinite number, which is an observation known as Gibbs phenomenon. This, then, requires an infinite number of Fourier coefficients, which is not practical for many applications, such as compression. Wavelets are more useful for describing these signals with discontinuities because of their time-localized behavior (both Fourier and wavelet transforms are frequency-localized, but wavelets have an additional time-localization property). Because of this, many types of signals in practice may be non-sparse in the Fourier domain, but very sparse in the wavelet domain. This is particularly useful in signal reconstruction, especially in the recently popular field of compressed sensing. (Note that the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) is also localized in time and frequency, but there are often problems with the frequency-time resolution trade-off. Wavelets are better signal representations because of multiresolution analysis.)

This motivates why wavelet transforms are now being adopted for a vast number of applications, often replacing the conventional Fourier transform. Many areas of physics have seen this paradigm shift, including molecular dynamics, chaos theory,[36] ab initio calculations, astrophysics, gravitational wave transient data analysis,[37][38] density-matrix localisation, seismology, optics, turbulence and quantum mechanics. This change has also occurred in image processing, EEG, EMG,[39] ECG analyses, brain rhythms, DNA analysis, protein analysis, climatology, human sexual response analysis,[40] general signal processing, speech recognition, acoustics, vibration signals,[41] computer graphics, multifractal analysis, and sparse coding. In computer vision and image processing, the notion of scale space representation and Gaussian derivative operators is regarded as a canonical multi-scale representation.

Wavelet denoising

[edit]

Suppose we measure a noisy signal , where represents the signal and represents the noise. Assume has a sparse representation in a certain wavelet basis, and

Let the wavelet transform of be , where is the wavelet transform of the signal component and is the wavelet transform of the noise component.

Most elements in are 0 or close to 0, and

Since is orthogonal, the estimation problem amounts to recovery of a signal in iid Gaussian noise. As is sparse, one method is to apply a Gaussian mixture model for .

Assume a prior , where is the variance of "significant" coefficients and is the variance of "insignificant" coefficients.

Then , is called the shrinkage factor, which depends on the prior variances and . By setting coefficients that fall below a shrinkage threshold to zero, once the inverse transform is applied, an expectedly small amount of signal is lost due to the sparsity assumption. The larger coefficients are expected to primarily represent signal due to sparsity, and statistically very little of the signal, albeit the majority of the noise, is expected to be represented in such lower magnitude coefficients... therefore the zeroing-out operation is expected to remove most of the noise and not much signal. Typically, the above-threshold coefficients are not modified during this process. Some algorithms for wavelet-based denoising may attenuate larger coefficients as well, based on a statistical estimate of the amount of noise expected to be removed by such an attenuation.

At last, apply the inverse wavelet transform to obtain

Multiscale climate network

[edit]Agarwal et al. proposed wavelet based advanced linear [42] and nonlinear [43] methods to construct and investigate Climate as complex networks at different timescales. Climate networks constructed using SST datasets at different timescale averred that wavelet based multi-scale analysis of climatic processes holds the promise of better understanding the system dynamics that may be missed when processes are analyzed at one timescale only [44]

List of wavelets

[edit]Discrete wavelets

[edit]- Beylkin (18)

- Moore Wavelet Morlet wavelet

- Biorthogonal nearly coiflet (BNC) wavelets

- Coiflet (6, 12, 18, 24, 30)

- Cohen-Daubechies-Feauveau wavelet (Sometimes referred to as CDF N/P or Daubechies biorthogonal wavelets)

- Daubechies wavelet (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, 20, etc.)

- Binomial QMF (Also referred to as Daubechies wavelet)

- Haar wavelet

- Mathieu wavelet

- Legendre wavelet

- Villasenor wavelet

- Symlet[45]

Continuous wavelets

[edit]Real-valued

[edit]- Beta wavelet

- Hermitian wavelet

- Meyer wavelet

- Mexican hat wavelet

- Poisson wavelet

- Shannon wavelet

- Spline wavelet

- Strömberg wavelet

Complex-valued

[edit]See also

[edit]- Chirplet transform

- Curvelet

- Digital cinema

- Dimension reduction

- Filter banks

- Fourier-related transforms

- Fractal compression

- Fractional Fourier transform

- Gabor wavelet § Wavelet space[46]

- Huygens–Fresnel principle (physical wavelets)

- JPEG 2000

- Least-squares spectral analysis for computing periodicity in any including unevenly spaced data

- Morlet wavelet

- Multiresolution analysis

- Noiselet

- Non-separable wavelet

- Scale space

- Scaled correlation

- Shearlet

- Short-time Fourier transform

- Spectrogram

- Ultra wideband radio – transmits wavelets

- Wavelet for multidimensional signals analysis

References

[edit]- ^ Wireless Communications: Principles and Practice, Prentice Hall communications engineering and emerging technologies series, T. S. Rappaport, Prentice Hall, 2002, p. 126.

- ^ Ricker, Norman (1953). "Wavelet Contraction, Wavelet Expansion, and the Control of Seismic Resolution". Geophysics. 18 (4): 769–792. Bibcode:1953Geop...18..769R. doi:10.1190/1.1437927.

- ^ "Continuous wavelet transform - Knowledge and References". Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ "Continuous wavelet transform - Knowledge and References". Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ Meyer, Yves (1992), Wavelets and Operators, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-42000-8

- ^ Chui, Charles K. (1992), An Introduction to Wavelets, San Diego, CA: Academic Press, ISBN 0-12-174584-8

- ^ Daubechies, Ingrid. (1992), Ten Lectures on Wavelets, SIAM, ISBN 978-0-89871-274-2

- ^ Akansu, Ali N.; Haddad, Richard A. (1992), Multiresolution Signal Decomposition: Transforms, Subbands, and Wavelets, Boston, MA: Academic Press, ISBN 978-0-12-047141-6

- ^ Larson, David R. (2007), Wavelet Analysis and Applications (See: Unitary systems and wavelet sets), Appl. Numer. Harmon. Anal., Birkhäuser, pp. 143–171

- ^ Szu, Harold H.; Telfer, Brian A.; Lohmann, Adolf W. (1992). "Causal analytical wavelet transform". Optical Engineering. 31 (9): 1825. Bibcode:1992OptEn..31.1825S. doi:10.1117/12.59911.

- ^ Lindeberg, T. (23 January 2023). "A time-causal and time-recursive scale-covariant scale-space representation of temporal signals and past time". Biological Cybernetics. 117 (1–2): 21–59. doi:10.1007/s00422-022-00953-6. PMC 10160219. PMID 36689001.

- ^ Mallat 2009, Chpt. 7.

- ^ The Scientist and Engineer's Guide to Digital Signal Processing By Steven W. Smith, Ph.D. chapter 8 equation 8-1: http://www.dspguide.com/ch8/4.htm

- ^ Haines, VG. V.; Jones, Alan G. (1988). "Logarithmic Fourier Transform" (PDF). Geophysical Journal (92): 171–178. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1988.tb01131.x. S2CID 9720759.

- ^ "A Really Friendly Guide To Wavelets – PolyValens". www.polyvalens.com.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Zweig, George -- from Eric Weisstein's World of Scientific Biography". scienceworld.wolfram.com. Retrieved 2021-10-20.

- ^ Sullivan, Gary (8–12 December 2003). "General characteristics and design considerations for temporal subband video coding". ITU-T. Video Coding Experts Group. Retrieved 13 September 2019.

- ^ Bovik, Alan C. (2009). The Essential Guide to Video Processing. Academic Press. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-08-092250-8.

- ^ Gall, Didier Le; Tabatabai, Ali J. (1988). "Sub-band coding of digital images using symmetric short kernel filters and arithmetic coding techniques". ICASSP-88., International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing. pp. 761–764 vol.2. doi:10.1109/ICASSP.1988.196696. S2CID 109186495.

- ^ Said, Amir; Pearlman, William A. (June 1996). "A new fast and efficient image codec based on set partitioning in hierarchical trees". IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology. 6 (3): 243–250. doi:10.1109/76.499834. ISSN 1051-8215.

- ^ Taubman, David; Marcellin, Michael (2012). JPEG2000 Image Compression Fundamentals, Standards and Practice: Image Compression Fundamentals, Standards and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4615-0799-4.

- ^ Unser, M.; Blu, T. (2003). "Mathematical properties of the JPEG2000 wavelet filters" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Image Processing. 12 (9): 1080–1090. Bibcode:2003ITIP...12.1080U. doi:10.1109/TIP.2003.812329. PMID 18237979. S2CID 2765169. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-10-13.

- ^ Swartz, Charles S. (2005). Understanding Digital Cinema: A Professional Handbook. Taylor & Francis. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-240-80617-4.

- ^ P. Hirsch, A. Howie, R. Nicholson, D. W. Pashley and M. J. Whelan (1965/1977) Electron microscopy of thin crystals (Butterworths, London/Krieger, Malabar FLA) ISBN 0-88275-376-2

- ^ P. Fraundorf, J. Wang, E. Mandell and M. Rose (2006) Digital darkfield tableaus, Microscopy and Microanalysis 12:S2, 1010–1011 (cf. arXiv:cond-mat/0403017)

- ^ Hÿtch, M. J.; Snoeck, E.; Kilaas, R. (1998). "Quantitative measurement of displacement and strain fields from HRTEM micrographs". Ultramicroscopy. 74 (3): 131–146. doi:10.1016/s0304-3991(98)00035-7.

- ^ Martin Rose (2006) Spacing measurements of lattice fringes in HRTEM image using digital darkfield decomposition (M.S. Thesis in Physics, U. Missouri – St. Louis)

- ^ F. G. Meyer and R. R. Coifman (1997) Applied and Computational Harmonic Analysis 4:147.

- ^ A. G. Flesia, H. Hel-Or, A. Averbuch, E. J. Candes, R. R. Coifman and D. L. Donoho (2001) Digital implementation of ridgelet packets (Academic Press, New York).

- ^ Shi, J.; Zhang, N.-T.; Liu, X.-P. (2011). "A novel fractional wavelet transform and its applications". Sci. China Inf. Sci. 55 (6): 1270–1279. doi:10.1007/s11432-011-4320-x. S2CID 255201598.

- ^ A.N. Akansu, W.A. Serdijn and I.W. Selesnick, Emerging applications of wavelets: A review, Physical Communication, Elsevier, vol. 3, issue 1, pp. 1-18, March 2010.

- ^ Tomás, R., Li, Z., Lopez-Sanchez, J.M., Liu, P. & Singleton, A. 2016. Using wavelet tools to analyse seasonal variations from InSAR time-series data: a case study of the Huangtupo landslide. Landslides, 13, 437-450, doi: 10.1007/s10346-015-0589-y.

- ^ Lyakhov, Pavel; Semyonova, Nataliya; Nagornov, Nikolay; Bergerman, Maxim; Abdulsalyamova, Albina (2023-11-14). "High-Speed Wavelet Image Processing Using the Winograd Method with Downsampling". Mathematics. 11 (22): 4644. doi:10.3390/math11224644. ISSN 2227-7390.

Wavelets are actively used to solve a wide range of image processing problems in various fields of science and technology, e.g., image denoising, reconstruction, analysis, and video analysis and processing. Wavelet processing methods are based on the discrete wavelet transform using 1D digital filtering.

- ^ Dong, Liang; Zhang, Shaohua; Gan, Tiansiyu; Qiu, Yan; Song, Qinfeng; Zhao, Yongtao (2023-12-01). "Frequency characteristics analysis of pipe-to-soil potential under metro stray current interference using continuous wavelet transform method". Construction and Building Materials. 407 133453. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.133453. ISSN 0950-0618. S2CID 263317973.

- ^ Stefano Galli; O. Logvinov (July 2008). "Recent Developments in the Standardization of Power Line Communications within the IEEE". IEEE Communications Magazine. 46 (7): 64–71. doi:10.1109/MCOM.2008.4557044. S2CID 2650873. An overview of P1901 PHY/MAC proposal.

- ^ Wotherspoon, T.; et., al. (2009). "Adaptation to the edge of chaos with random-wavelet feedback". J. Phys. Chem. 113 (1): 19–22. Bibcode:2009JPCA..113...19W. doi:10.1021/jp804420g. PMID 19072712.

- ^ Abbott, Benjamin P.; et al. (LIGO Scientific Collaboration and Virgo Collaboration) (2016). "Observing gravitational-wave transient GW150914 with minimal assumptions". Phys. Rev. D. 93 (12) 122004. arXiv:1602.03843. Bibcode:2016PhRvD..93l2004A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.93.122004. S2CID 119313566.

- ^ V Necula, S Klimenko and G Mitselmakher (2012). "Transient analysis with fast Wilson-Daubechies time-frequency transform". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 363 (1) 012032. Bibcode:2012JPhCS.363a2032N. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/363/1/012032.

- ^ J. Rafiee et al. Feature extraction of forearm EMG signals for prosthetics, Expert Systems with Applications 38 (2011) 4058–67.

- ^ J. Rafiee et al. Female sexual responses using signal processing techniques, The Journal of Sexual Medicine 6 (2009) 3086–96. (pdf) Archived 2013-08-10 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rafiee, J.; Tse, Peter W. (2009). "Use of autocorrelation in wavelet coefficients for fault diagnosis". Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing. 23 (5): 1554–72. Bibcode:2009MSSP...23.1554R. doi:10.1016/j.ymssp.2009.02.008.

- ^ Agarwal, Ankit; Maheswaran, Rathinasamy; Marwan, Norbert; Caesar, Levke; Kurths, Jürgen (November 2018). "Wavelet-based multiscale similarity measure for complex networks" (PDF). The European Physical Journal B. 91 (11): 296. Bibcode:2018EPJB...91..296A. doi:10.1140/epjb/e2018-90460-6. eISSN 1434-6036. ISSN 1434-6028. S2CID 125557123.

- ^ Agarwal, Ankit; Marwan, Norbert; Rathinasamy, Maheswaran; Merz, Bruno; Kurths, Jürgen (13 October 2017). "Multi-scale event synchronization analysis for unravelling climate processes: a wavelet-based approach". Nonlinear Processes in Geophysics. 24 (4): 599–611. Bibcode:2017NPGeo..24..599A. doi:10.5194/npg-24-599-2017. eISSN 1607-7946. S2CID 28114574.

- ^ Agarwal, Ankit; Caesar, Levke; Marwan, Norbert; Maheswaran, Rathinasamy; Merz, Bruno; Kurths, Jürgen (19 June 2019). "Network-based identification and characterization of teleconnections on different scales". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 8808. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.8808A. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45423-5. eISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6584743. PMID 31217490.

- ^ Matlab Toolbox – URL: http://matlab.izmiran.ru/help/toolbox/wavelet/ch06_a32.html

- ^ Erik Hjelmås (1999-01-21) Gabor Wavelets URL: http://www.ansatt.hig.no/erikh/papers/scia99/node6.html

Further reading

[edit]- Addison, Paul S. (2002). The illustrated wavelet transform handbook: introductory theory and applications in science, engineering, medicine and finance. Bristol Philadelphia: Institute of physics publ. ISBN 0-7503-0692-0.

- Akansu, Ali N.; Haddad, Richard A. (1992). Multiresolution signal decomposition: transforms, subbands, and wavelets. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-047140-X.

- Chan, Tony F.; Shen, Jianhong (2005). Image processing and analysis: variational, PDE, wavelet, and stochastic methods. Philadelphia: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. ISBN 0-89871-589-X. OCLC 60321765.

- Daubechies, Ingrid (1992). Ten lectures on wavelets. Philadelphia, Pa: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. ISBN 0-89871-274-2.

- Gençay, Ramazan; Selçuk, Faruk; Whitcher, Brandon (2002). An introduction to wavelets and other filtering methods in finance and economics. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-279670-5.

- Haar, Alfred (1910). "Zur Theorie der orthogonalen Funktionensysteme: Erste Mitteilung". Mathematische Annalen (in German). 69 (3): 331–371. doi:10.1007/BF01456326. ISSN 0025-5831. Retrieved 2024-12-28.

- Kaiser, Gerald (1994). A friendly guide to wavelets. Basel Boston: Birkhäuser. ISBN 0-8176-3711-7.

- Mallat, S. G. (2009). A wavelet tour of signal processing: the sparse way. Amsterdam ; Boston: Elsevier/Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-374370-1.X0001-8. ISBN 978-0-12-374370-1.

- Percival, Donald B.; Walden, Andrew T. (2007). Wavelet methods for time series analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68508-5.

- Press, William H. (2007). Numerical recipes: the art of scientific computing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88068-8. OCLC 1025448470.

- Vaidyanathan, P. P. (1993). Multirate systems and filter banks. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-605718-7.

- Vetterli, Martin; Kovačević, Jelena (1995). Wavelets and subband coding. Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice Hall PTR. ISBN 0-13-097080-8.

- Wickerhauser, Mladen Victor (1994). Adapted wavelet analysis from theory to software. Wellesley, MA: A.K. Peters. ISBN 1-56881-041-5.

External links

[edit]- "Wavelet analysis", Encyclopedia of Mathematics, EMS Press, 2001 [1994]

- 1st NJIT Symposium on Wavelets (First Wavelets Conference in USA)

Wavelet

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Etymology

The term "wavelet" derives from the English word "wave" combined with the diminutive suffix "-let," denoting a small or little wave, which captures the essence of these functions as brief, localized oscillations suitable for analyzing signals at various scales.[5] In the context of mathematical wavelet theory, the term was first employed by geophysicist Jean Morlet and mathematician Alex Grossmann in their 1984 paper, where it described square-integrable functions of constant shape used for decomposing Hardy functions in signal analysis.[6] This usage built on the French equivalent "ondelette," reflecting the innovative application of small-wave-like basis functions.[7] The terminology's roots trace back to early 20th-century developments in harmonic analysis, such as Alfred Haar's 1909 construction of simple orthogonal step functions that later became known as the first wavelets, though without the specific nomenclature at the time.[8] By the 1980s, with the rise of computational signal processing, the term "wavelet" became standard in English-language literature, notably through Yves Meyer's foundational work on orthogonal wavelets, marking its first prominent appearances in that context.[9] (Note: An earlier, unrelated use of "wavelet" appeared in geophysics, where Norman Ricker applied it in 1940 to model finite-duration seismic pulses.)[10]Basic Definition and Overview

A wavelet is a mathematical function that exhibits wave-like oscillatory behavior with finite duration and limited frequency bandwidth, enabling localized analysis in both time and frequency domains. Unlike global transforms such as the Fourier transform, wavelets are generated by scaling and translating a prototype function, known as the mother wavelet ψ(t), to form a family of basis functions suitable for decomposing signals. This structure allows wavelets to capture transient features effectively, representing them as small waves that oscillate briefly and decay to near zero, often featuring compact support in time.[11][12] Key properties of a wavelet include square-integrability, ensuring the function belongs to the space L²(ℝ) of square-integrable functions over the real line, which guarantees finite energy: ∫ |ψ(t)|² dt < ∞. Additionally, wavelets satisfy the admissibility condition, characterized by a finite admissibility constant C_ψ = ∫{-∞}^∞ |Ψ(ω)|² / |ω| dω < ∞, where Ψ(ω) is the Fourier transform of ψ(t); this condition implies that the wavelet has zero mean, expressed as ∫{-∞}^∞ ψ(t) dt = 0, allowing perfect reconstruction of signals via the inverse transform. Wavelets also possess vanishing moments, meaning ∫_{-∞}^∞ t^n ψ(t) dt = 0 for n = 0, 1, ..., M-1, where M is the order of vanishing moments; this property enhances the approximation of smooth signals by making wavelet coefficients sparse for polynomials up to degree M-1.[12][13][11] In signal analysis, wavelets excel at time-frequency localization, providing variable resolution that adapts to the signal's characteristics—higher resolution in time for high-frequency components and in frequency for low-frequency ones. This makes them particularly superior for processing non-stationary signals, where frequency content varies over time, such as in seismic data or speech, by revealing localized events without the fixed window limitations of other methods.[14][11]Mathematical Foundations

Scaling Function and Filter

The scaling function, denoted , is a cornerstone of wavelet construction in discrete wavelet transforms and multiresolution analysis. It is defined as the unique -normalized solution to the dilation equation (or refinement equation): where are the coefficients of a low-pass filter satisfying to ensure . This equation expresses the scaling function at a given scale as a linear combination of its dilated and translated versions, enabling iterative refinement in wavelet decompositions.[15][16] In multiresolution analysis, the translates and dilates of generate nested approximation spaces , where and is dense in , capturing low-frequency components at dyadic scales . Key properties include orthogonality, achieved when the filter satisfies the quadrature mirror filter condition , ensuring forms an orthonormal basis for ; regularity, which measures smoothness and increases with the filter length (e.g., linearly for Daubechies wavelets), determined by the number of zeros of the filter's Fourier transform at ; and compact support, where for a filter of length , facilitating efficient computation. These properties balance localization in time and frequency, essential for practical implementations.[16][15] A canonical example is the Haar scaling function, the simplest orthogonal case, given by (the indicator function on ), with low-pass filter coefficients . This piecewise constant function has compact support of length 1 and zero regularity beyond discontinuities but forms the basis for the original Haar wavelet system.[15] The solution to the dilation equation can be obtained iteratively, starting from an initial approximation (e.g., a rectangular pulse) and refining through repeated application of the filter, converging in the norm under stability conditions on . In the Fourier domain, this yields the infinite product representation: where is the Fourier transform of the filter, with the product ensuring and decay for stability. This formulation highlights the self-similar, fractal-like structure of .[15]Wavelet Function

The wavelet function is generated from the scaling function through a two-scale dilation equation that captures high-frequency details orthogonal to the low-frequency approximations spanned by . Specifically, for orthogonal wavelets, it is defined as where the coefficients are derived from the low-pass filter coefficients associated with the scaling function, ensuring the wavelet acts as a high-pass filter.[15] This construction, part of the multiresolution framework, positions the wavelet function to extract differences between finer and coarser approximation spaces.[16] Key properties of the wavelet function enable its role in localized signal analysis. It exhibits oscillatory behavior, characterized by a zero mean , which allows it to detect variations rather than constant offsets.[15] Many orthogonal wavelets possess compact support, meaning is nonzero only over a finite interval, facilitating efficient computation and localization in time.[15] Additionally, the number of vanishing moments—defined as the largest integer such that for —determines the wavelet's ability to approximate polynomials; higher vanishing moments imply orthogonality to low-degree polynomials, enhancing the approximation of smooth signals by the scaling spaces.[15] In the multiresolution analysis, the wavelet function relates directly to the detail spaces , which represent the orthogonal complement of the approximation space in the finer space , i.e., . The translated and dilated versions form an orthonormal basis for , capturing incremental details at scale .[16] This decomposition satisfies the perfect reconstruction condition, where the full signal in can be recovered exactly as low-frequency component, due to the orthonormality of the basis.[15] In the frequency domain, the wavelet function is characterized by its Fourier transform , which satisfies to enforce the zero mean and exhibits bandpass behavior, concentrating energy away from zero and high frequencies depending on the filter design. For orthogonal wavelets, the relation is given by where is the Fourier transform of the high-pass filter coefficients , typically with the low-pass filter transform, ensuring orthogonality via .[15] This frequency characterization underscores the wavelet's role in isolating scale-specific frequency bands while maintaining time localization.Mother Wavelet

The mother wavelet, denoted as , serves as the prototype function in wavelet theory from which an entire family of wavelets is generated through operations of scaling and translation. This generating function must belong to the space and typically exhibits oscillatory behavior with finite energy and zero mean. The scaled and translated versions, known as daughter wavelets, are defined by the equation where is the scale parameter controlling the dilation or compression of the wavelet, and is the translation parameter shifting its position along the time axis. The normalization factor preserves the -norm of the wavelet across different scales, ensuring consistent energy measurement in applications.[12] A critical selection criterion for the mother wavelet, particularly in the context of the continuous wavelet transform, is the admissibility condition, which guarantees the invertibility of the transform. This condition requires that the admissibility constant be finite, given by where is the Fourier transform of . The finiteness of implies that , or equivalently , ensuring the wavelet has no DC component and allowing perfect reconstruction of the original signal. This criterion was formalized in the foundational work linking wavelet decompositions to square-integrable representations.[12][17] Prominent examples of mother wavelets illustrate diverse properties suited to different analytical needs. The Haar mother wavelet, the simplest orthogonal wavelet, is explicitly defined piecewise as It features compact support on , one vanishing moment, and discontinuity, making it ideal for detecting abrupt changes but limited in smoothness. In contrast, Daubechies wavelets form a family of orthogonal mother wavelets with compact support and increasing regularity; for instance, the Db1 (or D1) wavelet is the Haar, while higher-order ones, such as Db4, are defined via filter coefficients without a simple closed-form expression but possess support on [0, 7] (for Db4), four vanishing moments, and approximately C^{1.6} smoothness, enabling better approximation of smooth signals. These properties arise from constructing the wavelet to satisfy orthogonality and maximal flatness conditions in the frequency domain. The Morlet mother wavelet, originally developed for seismic analysis, is a complex-valued function approximating a Gaussian-modulated plane wave: with for admissibility; it offers excellent time-frequency localization due to its Gaussian envelope but infinite support, prioritizing resolution in continuous transforms over computational efficiency.[18][15]Comparisons with Other Transforms

With Fourier Transform

The Fourier transform decomposes a signal into global sinusoidal basis functions, providing frequency information across the entire domain but failing to localize events in time, particularly for non-stationary signals where frequency content varies over time. This limitation arises because the basis functions, such as complex exponentials , extend infinitely in time, spreading energy uniformly and requiring numerous coefficients to represent localized transients like edges or abrupt changes. For instance, the Fourier transform of a signal is given by which captures global frequency content but obscures temporal dynamics, leading to phenomena like Gibbs oscillations near discontinuities.[19] In contrast, wavelet transforms address these shortcomings by employing basis functions that are localized in both time and frequency, achieved through dilations and translations of a mother wavelet, enabling variable window sizes that adapt to the signal's scale. This provides superior time-frequency resolution for non-stationary signals, allowing analysis of how frequencies evolve locally without the global averaging inherent in Fourier methods. Wavelets thus offer a more flexible representation, concentrating energy near singularities and reducing the number of significant coefficients needed for sparse approximations.[19] These advantages stem from implications of the time-frequency uncertainty principle, which states that the product of time and frequency spreads satisfies , limiting simultaneous precise localization in both domains. The Fourier transform achieves optimal frequency resolution but at the expense of time spread, whereas wavelets attain a better joint time-frequency spread by varying the scale parameter, balancing the trade-off more effectively for signals with multiscale features.[19]With Short-Time Fourier Transform

The short-time Fourier transform (STFT) provides a time-frequency representation of a signal by applying a fixed-duration window to localize the Fourier transform in time. It is mathematically defined as where is the input signal, is the window function (typically of fixed width), denotes time shift, and denotes frequency.[20] This formulation computes the Fourier transform of the signal multiplied by a shifted version of the window, yielding a two-dimensional time-frequency map. The fixed window width, such as a Gaussian , ensures consistent temporal resolution across all frequencies but limits adaptability to signals with varying scales.[20] A key limitation of the STFT arises from the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, which imposes a lower bound on the product of time and frequency resolutions: , where and are the standard deviations in the time and frequency domains, respectively.[21] This fixed resolution trade-off results in either poor temporal localization for high-frequency components (with a wide window) or inadequate frequency resolution for low-frequency components (with a narrow window), making the STFT suboptimal for analyzing non-stationary signals exhibiting multi-scale features, such as transients or chirps. The spectrogram, defined as , further illustrates this by providing an energy density estimate but suffering from smeared representations due to the uniform window, without the oscillating cross-terms prevalent in other quadratic time-frequency distributions like the Wigner-Ville distribution.[22] In contrast, wavelet transforms achieve superiority over the STFT through multi-resolution analysis, where the analyzing function is dilated to adaptively adjust time and frequency resolutions according to the signal's local scales—offering finer temporal detail at high frequencies and better frequency detail at low frequencies. This dilation-based approach overcomes the STFT's rigid Heisenberg constraint by varying the effective window width with scale, enabling more precise localization of multi-scale phenomena without the resolution compromises inherent in fixed-window methods. The Gabor transform serves as a specific example of an STFT variant using a Gaussian window, which minimizes the uncertainty product but still retains the fixed-width limitation, highlighting why wavelets provide enhanced flexibility for signals with heterogeneous frequency content. Quadratic time-frequency distributions, including the STFT spectrogram, mitigate severe cross-term interference through kernel smoothing but at the expense of reduced resolution, whereas wavelets inherently avoid such artifacts by design in their linear, scale-adapted framework.[22]Core Wavelet Theory

Continuous Wavelet Transform

The continuous wavelet transform (CWT) provides a time-scale representation of signals, particularly suited for analyzing nonstationary phenomena in continuous-time signals belonging to the space . Introduced by Grossmann and Morlet, it decomposes a function using a family of dilated and translated versions of a mother wavelet , where satisfies the admissibility condition ensuring zero mean and finite energy concentration. The transform is defined as with continuous parameters (scale) and (translation). This formulation correlates the signal with wavelets of varying widths and positions, allowing localization of features in both time and scale domains. A key property of the CWT is its invertibility, enabling perfect reconstruction of the original signal under the admissibility condition. The constant (where is the Fourier transform of ) ensures the transform is a frame for . The reconstruction formula is Additionally, the CWT satisfies a Plancherel theorem, preserving the -norm of the signal: for an admissible wavelet normalized such that , These properties underpin the CWT's utility in theoretical analysis of continuous-time signals. In signal processing, the CWT facilitates ridge detection to identify prominent features such as transients or singularities. Ridges correspond to curves in the time-scale plane where the modulus achieves local maxima, often aligning with the instantaneous frequency of oscillatory components in the signal; for example, in a chirp signal, ridges trace frequency variations over time. This technique extracts skeletal structures of signals, enabling characterization of nonstationary behaviors like abrupt changes or modulated oscillations. The CWT's continuous parameterization supports applications in continuous-time analysis, including seismic wave propagation and gravitational wave detection, where it reveals time-varying spectral content without discrete approximations.Discrete Wavelet Transform

The discrete wavelet transform (DWT) is a mathematical operation that computes wavelet coefficients for a signal by discretizing the continuous wavelet transform parameters on a dyadic grid, where the scale parameter and translation parameter for integers .[23] This discretization enables efficient computation while preserving key properties of the continuous transform, such as localization in time and frequency. The wavelet coefficients are defined as where is the input signal, is the mother wavelet, and denotes its complex conjugate.[16] This formulation arises from sampling the continuous wavelet transform at dyadic locations to approximate the integral efficiently for discrete signals.[23] In practice, the DWT is implemented via convolution of the signal with dilated and translated versions of the wavelet and its associated scaling function, followed by downsampling. The coefficients can thus be expressed as , where is the appropriately normalized and shifted wavelet, and denotes convolution.[24] A seminal fast algorithm for computing the DWT is Mallat's pyramid algorithm, which uses a bank of quadrature mirror filters: a low-pass filter for approximations and a high-pass filter for details.[16] Decomposition proceeds recursively by convolving the signal with these filters and subsampling by a factor of 2 at each level, producing a pyramid of coefficient arrays that capture multiscale features. Reconstruction is achieved by upsampling and convolving with the synthesis filters, ensuring invertibility. For orthogonal DWTs, such as those based on Daubechies wavelets, the filter banks satisfy perfect reconstruction conditions, allowing lossless recovery of the original signal from the coefficients via the inverse transform.[16] This orthogonality implies that the wavelet basis functions are orthonormal, minimizing redundancy and enabling energy-preserving decompositions. Undecimated versions of the DWT, also known as the stationary wavelet transform or à trous algorithm, omit the downsampling step to maintain translation invariance, resulting in oversampled coefficients that are useful for applications requiring shift robustness, such as denoising. These variants compute coefficients at full resolution across scales by inserting zeros into the filters at each level, bridging the Mallat pyramid with non-decimated approaches.Multiresolution Analysis

Multiresolution analysis (MRA) is a foundational framework in wavelet theory that organizes the Hilbert space into a sequence of nested closed subspaces , enabling the construction of wavelet bases through hierarchical approximations at dyadic scales. This structure captures signal details at multiple resolutions, where represents approximations of functions in at scale .[16] The subspaces satisfy the inclusion relation for all , ensuring coarser approximations are contained within finer ones. The union is dense in , allowing arbitrary functions to be approximated arbitrarily well at sufficiently fine scales, while the intersection , meaning only the zero function is common to all scales. The framework exhibits dilatation invariance: a function if and only if the dilated version .[16] Translation invariance holds such that shifts by integers preserve membership in , and the integer translates of a scaling function form a Riesz basis for . The scaling function generates the entire MRA, with the family forming a Riesz basis for . This basis satisfies Riesz bounds, ensuring stable reconstructions without redundancy, and extends the approximation properties across scales. Complementing the approximation spaces, the wavelet spaces are defined as , the orthogonal complement of in , capturing high-frequency details at scale .[16] These spaces satisfy and for , with , leading to the orthogonal direct sum decomposition . Each admits a Riesz basis generated by dilations and translations of a mother wavelet . This structure allows any to be uniquely represented in the wavelet basis as where the first sum projects onto the approximation spaces and the second onto the detail spaces, with orthogonality ensuring Parseval's identity .[16] The orthogonality conditions arise from the complementary nature of the spaces, guaranteeing that inner products between basis functions from different and vanish when appropriate.Advanced Topics

Time-Causal Wavelets

Time-causal wavelets are mathematical functions with support confined to the non-negative real line, [0, ∞), enabling forward-only analysis that depends solely on past and present data without accessing future information. This design is essential for real-time signal processing applications where causality constraints must be respected, such as in online monitoring systems or live data streams. Unlike traditional wavelets with symmetric or bidirectional support, time-causal variants ensure that the transform output at any time instant is computable instantaneously upon signal arrival. Key properties of time-causal wavelets include progressive multiresolution analysis, which prevents the creation of new temporal structures as scale increases from finer to coarser levels, and adherence to scale-space axioms adapted for causality. These axioms enforce variation-diminishing properties through convolutions with one-sided kernels, ensuring that the representation remains stable and non-expansive over time-recursive scales. Additionally, temporal scale covariance holds under discrete scaling factors (where is a constant and ), preserving the signal's structure when time is dilated by and scale by . This framework adapts standard multiresolution analysis principles to enforce time-directionality, supporting efficient computation via cascades of first-order recursive filters.[25] Early developments in time-causal wavelets trace to the causal analytical wavelet transform introduced by Szu, Telfer, and Lohmann in 1992,[26] which employs exponentially decaying, nonsinusoidal wideband transient bases of compact support to achieve completeness while maintaining causality. The mother wavelet in this approach is strictly zero for and analytical for , with daughter wavelets generated as for scale and translation . More recent advancements by Lindeberg in 2025 extended this to time-recursive filters, deriving time-causal wavelets as temporal derivatives of a limit kernel for , where ensures one-sided support. The n-th order mother wavelet is then normalized as , enabling progressive multiresolution with minimal buffering for real-time use.[25]Generalized Wavelet Transforms

Generalized wavelet transforms extend the foundational continuous and discrete wavelet frameworks by incorporating additional parameters, such as fractional orders or canonical transformations, to better capture non-stationary and multidimensional signal behaviors. These extensions address limitations in standard transforms, particularly for signals with varying frequency modulations or anisotropic features, enabling more flexible time-frequency representations.[27] The fractional wavelet transform (FrWT) introduces a fractional order parameter α ∈ [0,1] into the dilation operation, generalizing the classical wavelet transform to analyze signals in a fractional time-frequency domain. Defined as where ψ_α is a fractional mother wavelet derived via the fractional Fourier transform of a standard wavelet, the FrWT preserves admissibility conditions while allowing interpolation between time and frequency domains. This leads to improved resolution for chirp-like non-stationary signals, such as those in radar and sonar applications, where traditional wavelets struggle with rapid frequency changes. For instance, FrWT enhances the detection of linear frequency-modulated chirps by adjusting α to match the signal's chirp rate, achieving lower mean square error in reconstruction compared to standard methods.[28][29][30] Complex wavelets extend real-valued wavelets by producing analytic coefficients with phase information, mitigating the shift-variance and poor directionality of discrete wavelet transforms. The dual-tree complex wavelet transform (DTCWT), a prominent implementation, uses two parallel wavelet trees to generate real and imaginary parts, yielding nearly shift-invariant representations with six directional subbands in 2D. This structure improves sparsity for edge detection in images, as the phase provides orientation cues absent in real wavelets. Complex wavelets are particularly effective in denoising non-stationary signals, where magnitude thresholding preserves directional features.[31] Shearlets generalize wavelets to higher dimensions by incorporating shear matrices alongside dilations and translations, providing anisotropic support that captures directional singularities like curves and edges more efficiently than isotropic wavelets. In n dimensions, the continuous shearlet transform is formulated as with ψ_{a,s} generated by anisotropic dilations and shears, offering O(N^{-2}) approximation rates for cartoon-like images—optimal up to a logarithmic factor. This enhanced directionality and sparsity make shearlets superior for multidimensional data, such as volumetric medical imaging, where standard wavelets fail to sparsely represent hyperbolic or curvilinear features. Complex shearlets further refine this by introducing Hilbert-like analyticity, boosting phase-based analysis for texture discrimination.[32][33] Ridgelet-wavelet frame hybrids combine ridgelets, which excel at representing line singularities via Radon transforms, with wavelet frames to handle both point and linear discontinuities in images. In these systems, ridgelets process directional components after wavelet decomposition of isotropic parts, achieving sparser approximations for natural images with edges—up to 20% fewer coefficients than pure wavelets for the same distortion level. This hybrid approach enhances compression and feature extraction in 2D signals, balancing the multiscale locality of wavelets with ridgelets' linearity sensitivity.[34][35] Recent developments in linear canonical wavelet transforms (LCWT) integrate the linear canonical transform (LCT), a chirp-modulated generalization of the Fourier transform, to handle signals under affine deformations. The LCWT is defined with LCT-parameterized dilations, preserving inversion and reproducing kernel properties while adapting to non-stationary chirps in optics and communications. In 2025, extensions like the polar LCWT and offset LCWT have emerged, incorporating polar coordinates or multidimensional offsets for rotation-invariant analysis of radial signals, with applications in image encryption showing improved security via fractional chirp multiplexing. These variants demonstrate bounded L^2 norms and Plancherel-type theorems, facilitating sparse representations in deformed domains.[36][37][38]History

Key Contributors and Early Development

The foundations of wavelet theory trace back to early 20th-century developments in harmonic analysis, particularly the Littlewood-Paley decompositions introduced in the 1930s by mathematicians John E. Littlewood and Raymond C. Paley. These decompositions provided a method for breaking down functions into dyadic frequency bands, enabling the analysis of localized frequency content in a manner that foreshadowed wavelet techniques for multiscale signal decomposition. Similarly, the work on Calderón-Zygmund operators, developed by Alberto P. Calderón and Antoni Zygmund in the mid-20th century but rooted in 1930s singular integral theory, established frameworks for boundedness and decomposition operators that later underpinned wavelet constructions in harmonic analysis. A pivotal early contribution came from Hungarian mathematician Alfréd Haar in 1909, who constructed the first known example of an orthonormal basis for the space of square-integrable functions on the real line, now recognized as the Haar wavelet system. Haar's orthogonal functions, defined piecewise as constants and step functions, provided a simple yet foundational tool for representing functions hierarchically, influencing subsequent wavelet designs despite their limited smoothness. The modern inception of wavelet theory occurred in the 1980s, driven by geophysicist Jean Morlet's practical needs for analyzing seismic signals with localized time-frequency resolution. In 1984, Morlet collaborated with physicist Alex Grossmann to formalize the continuous wavelet transform (CWT), introducing a mathematical framework that decomposed signals using scalable, translatable wavelets of constant shape, as detailed in their seminal paper. This work bridged applied signal processing with theoretical harmonic analysis, establishing the CWT as a cornerstone for non-stationary data analysis. Key advancements in discrete wavelet theory followed soon after, with Ingrid Daubechies constructing the first family of compactly supported orthogonal wavelets in 1988. These Daubechies wavelets, also known as DbN wavelets, achieved arbitrary regularity while maintaining finite support, enabling efficient computational implementations for signal compression and multiresolution analysis without the infinite extent issues of earlier continuous wavelets.[15] Parallel to these developments, French mathematician Yves Meyer advanced the continuous wavelet framework through his contributions to harmonic analysis, including the Meyer wavelet, which is infinitely differentiable and band-limited in frequency. Meyer's work in the 1980s and 1990s synthesized wavelet theory with Calderón-Zygmund operator techniques, providing rigorous proofs of invertibility and characterization of function spaces, as elaborated in his influential texts and earning him the 2017 Abel Prize for foundational impacts on wavelet applications.Timeline of Milestones

The development of wavelet theory spans over a century, marked by key mathematical and computational advancements that have progressively enhanced signal analysis and representation techniques.- 1909: Alfred Haar introduces the first example of an orthogonal wavelet basis, known as Haar wavelets, providing a simple step function basis for function decomposition on the interval [0,1].

- 1930s: John E. Littlewood and Raymond Paley develop the Littlewood-Paley theory, which decomposes functions into dyadic frequency bands using smooth window functions, laying foundational groundwork for localized frequency analysis that later influenced wavelet constructions.

- 1984: Jean Morlet and Alexandre Grossmann formalize the continuous wavelet transform (CWT) in their seminal paper, enabling the decomposition of signals into wavelets of constant shape for time-frequency analysis, particularly suited for non-stationary signals in geophysics.

- 1989: Stéphane Mallat proposes the fast pyramid algorithm for the discrete wavelet transform (DWT), based on multiresolution analysis and quadrature mirror filters, enabling efficient O(N) computation of wavelet coefficients for practical signal processing applications.[16]

- 1996: Amir Said and William A. Pearlman introduce the Set Partitioning in Hierarchical Trees (SPIHT) algorithm, an embedded zerotree wavelet coding method that achieves state-of-the-art image compression performance by exploiting the hierarchical structure of wavelet coefficients.

- 2000: The JPEG 2000 standard is finalized by the Joint Photographic Experts Group, adopting discrete wavelet transforms (specifically the 9/7 biorthogonal wavelet) as its core technology for superior lossless and lossy image compression compared to the original JPEG.[39]

- Early 2000s: Emmanuel Candès and David Donoho develop curvelets (around 2000) and shearlets (around 2006), extending wavelet theory to better capture curvilinear singularities in two-dimensional images, improving sparse representations for applications like edge detection and image denoising.[40]

- Post-2020: Hybrid wavelet-AI models emerge, integrating wavelet transforms with deep learning architectures such as convolutional neural networks for enhanced feature extraction in signal processing, with notable applications in time-series forecasting and anomaly detection.

- 2013-2023: Wavelet-AI integrations advance in healthcare, combining wavelet decomposition for multi-scale signal analysis with machine learning for tasks like ECG denoising and medical image segmentation, as evidenced by systematic reviews of over 100 studies showing improved diagnostic accuracy.[41]

- 2023: Tony Lindeberg extends wavelet theory to time-causal and time-recursive frameworks within scale-space representations, enabling real-time analysis of temporal signals by ensuring causality and recursion in scale levels for applications in computer vision and neuroscience.[42]

- 2025: Extensions of the Dunkl transform to wavelet frameworks are developed, incorporating rational Dunkl operators for generalized translations and dilations, providing new tools for analyzing signals in reflection-invariant settings relevant to quantum mechanics and special functions.[43]