Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

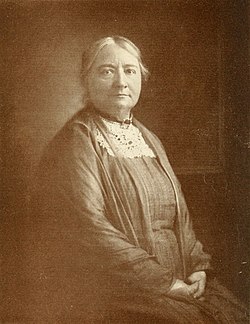

Ellen Key

View on WikipediaEllen Karolina Sofia Key (Swedish: [ˈkej]; 11 December 1849 – 25 April 1926) was a Swedish difference feminist writer on many subjects in the fields of family life, ethics and education and was an important figure in the Modern Breakthrough movement. She was an early advocate of a child-centered approach to education and parenting, and was also a suffragist.

Key Information

She is best known for her book on education Barnets århundrade (1900), which was translated into English in 1909 as The Century of the Child.[1]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]Ellen Key was born at Sundsholm mansion in Småland, Sweden, on 11 December 1849.[2] Her father was Emil Key, the founder of the Swedish Agrarian Party and a frequent contributor to the Swedish newspaper Aftonposten. Her mother was Sophie Posse Key, who was born into an aristocratic family from the southernmost part of Skåne County. Emil bought Sundsholm at the time of his wedding; twenty years later he sold it for financial reasons.[3]

Key was mostly educated at home, where her mother taught her grammar and arithmetic and her foreign-born governess taught her foreign languages. She cited reading Amtmandens Døtre (The Official's Daughters, 1855) by Camilla Collett and Henrik Ibsen's plays Kjærlighedens komedie (Love's Comedy, 1862), Brand (1865), and Peer Gynt (1867) as her childhood influences. When she was twenty years old, her father was elected to the Riksdag and they moved to Stockholm, where she would capitalize on the access to libraries.[3] Key also studied at the progressive Rossander Course.[4]

1870s

[edit]After a correspondence with Urban von Feilitzen, who wrote Protestantismens Maria-kult (The Protestant Cult of Mary, 1874), she had written a review of the book for a periodical, under the pseudonym Robinson. His book gave her thoughts structure, helping to define her beliefs concerning the role of women as mothers and nurturers. Key hoped Feilitzen would leave his wife, as they did not share similar interests, but he refused.[3]

In the summer of 1874, Key traveled to Denmark and studied their folk colleges. Folk colleges were institutions of higher learning for young people from the countryside. One of her early ambitions was to found a Swedish folk high school, but instead she decided, in 1880, to become a teacher at Anna Whitlock's school for girls in Stockholm.[3]

Shortly after she moved to Stockholm, she befriended Sophie Adlersparre, who was the editor of Tidskrift för Hemmet (Journal for the Home), founded in 1859 by Adlersparre and Rosalie Olivecrona. In 1874 Tidskrift för Hemmet published her first article. It was about Camilla Collett, and other articles soon followed. She would also do some biographical studies on George Eliot and Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The Fredrika Bremer Association, the liberal women's organization, was founded in 1884. Many of the writers for Tidskrift för Hemmet were members.[3]

1880s

[edit]In 1883, Key began teaching at Anton Nyström new school, the People's Institute, which was founded in 1880. She also helped organize "The Twelves", a group of twelve upper class ladies who sponsored and organized social functions to help improve working class ladies' manners.[3]

In 1885, she was one of the five founding members of the women's society Nya Idun, along with Calla Curman, Hanna Winge, Ellen Fries, and Amelie Wikström.[5][6] She also spoke at Curman's "Curman receptions", salons held several times a year which featured a number of the intellectuals of the day.[7]

Even though Key did share a lot of similar beliefs with the members of the Fredrika Bremer Association, two main issues made her oppose the group in the mid-1880s: the importance of sexuality and the social significance of the biological differences between women and men. 1886 saw Key publishing Om reaktionen mot kvinnofrågan (On the Reaction against the Woman Question) which was highly critical and argued against the egalitarian tendencies of the Swedish women's movement. The piece was published in Gustaf af Geijerstam's journal Revy i litterära och sociala frågor (Review of Literary and Social Issues).[3]

Also in 1886, she wrote a review of En sommarsaga (A Summer Story, 1886) by Anne Charlotte Leffler in the short-lived journal Framåt (Forward). She was critical of the piece for having one woman's attempt to combine marriage, motherhood, and a career as an artist.[3] In 1886, she became one of the founders of the Swedish Dress Reform Society.

Key contributed to three journals all with different views on women's rights: Tidskrift för Hemmet, Dagny, and Framåt. The latter was edited by Alma Åkermark from Gothenburg and tended to have taboo information, including publishing texts on syphilis, sexual repression and socialism. Mathilda Malling's Pyrrhus-segrar (Pyrrhic Victories), published in 1886 under the pseudonym Stella Kleve, was very controversial among Scandinavian intellectuals. The story dealt with a dying young woman, who laments that if she had done the things she wanted to do, she may not be dying.[3]

Also in Naturenliga arbetsområden för kvinnan (Natural Lines of Work for Women) and Kvinnopsykologi och kvinnlig logik (Female Psychology and Logic, 1896) Key said a "monogamous heterosexual relationship aimed toward procreation formed the crux of a woman's happiness and fulfillment."[3]

In 1889, she published Några tankar om huru reaktioner uppstå, jämte ett genmäle till d:r Carl v. Bergen, samt om yttrande och tryckfrihet (Some Thoughts about How Reactions Begin), which marked her a social radical, which she would never deny.[3]

Changing views

[edit]Key grew up in an atmosphere of liberalism, and throughout the 1870s her political beliefs were radically liberal. She was republican-minded, with the idea of freedom holding vast importance for her. As the 1880s advanced, her thinking became even more radical, affecting first her religious beliefs and then her views on life in society in general. This was the outcome of extensive reading. During the latter part of the 1880s and particularly in the 1890s, she began to read socialist literature and turned increasingly towards socialism.[citation needed]

Key was raised in a rigid Christian household, but while growing up she started questioning her views. From 1879 she studied Charles Darwin, Herbert Spencer and T. H. Huxley. In the autumn of that year she met both Huxley and Haeckel, the German biologist and philosopher, in London. The principle of evolution, in which Key had come to believe, was also to have an influence on her educational views.

She is quoted as having said:

- "Side by side with the class war, the culture war must ceaselessly be waged by the young and among the young upon whom rests the responsibility of making the new society better for all than the old could be."

Later life

[edit]In the late 1880s–early 1890s, Key decided to write biographies of women who had prominent roles in Swedish intellectual life; they were: Victoria Benedictsson, Anne Charlotte Leffler, and Sonia Kovalevsky. She would also write about Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Carl Jonas Love Almqvist.

In 1892 Key and Amalia Fahlstedt co-founded Tolfterna, an association which connected working women with educated middle-class women.[8]

The Cambridge Chronicle of Cambridge, Massachusetts on October 19, 1912 noted that in The Atlantic Monthly, Ellen Key, the Swedish writer, who has had such immense influence over the woman movement throughout Europe, makes her first appearance in an American periodical with her article on "Motherliness".[9] The Woman Movement by Key was published in Swedish in 1909, and in an English translation in 1912 by G. P. Putnam's Sons.[10]

After she retired from teaching, she met and helped the young poet Rainer Maria Rilke.[citation needed] She was later painted by Hanna Pauli. Die Antifeministen (The Antifeminists, 1902) by Hedwig Dohm cited both Key and Lou Andreas-Salomé as anti-feminists.[3]

She died on 25 April 1926 at the age of 76.[3]

Selected works

[edit]Key started her career as a writer in the mid-1870s with literary essays. She became known to a large public through the pamphlet On Freedom of Speech and Publishing (1889). Her name and her books then became the topic of lively discussions. The following work focuses on her views on education, personal freedom, and the independent development of the individual.[citation needed] These works include:

- Individualism and Socialism (1896)

- Images of Thought (1898)

- Human-beings (1899)

- Lifelines, volumes I-III (1903–06)

- Neutrality of the Souls (1916).

On education, her earliest article may be Teachers for Infants at Home and in School in Tidskrift för hemmet (1876). Her first more widely read essay, Books versus Coursebooks, was published in the journal Verdandi (1884). Later, in the same journal, she published other articles A Statement on Co-Education (1888) and Murdering the Soul in Schools (1891). Later she published the works Education (1897) and Beauty for All (1899).

In 1906 came Popular Education with Special Consideration for the Development of Aesthetic Sense. In the last books Key views aesthetics, as beauty and art, from the aspect of the elevation of humanity.[11]

Several of Key's writings were translated into English by Mamah Borthwick, during the period of her affair with Frank Lloyd Wright.[12] Among her best-known works published in English:

- The Morality of Woman (1911)

- Love and Marriage (1911, repr. with critical and biographical notes by Havelock Ellis, 1931)

- The Century of the Child (1909)

- The Woman Movement (1912)

- The Younger Generation (1914)

- War, Peace, and the Future (1916).[13]

Legacy

[edit]She has inspired writers such as Selma Lagerlöf, Marika Stjernstedt, Waka Yamada and Elin Wägner. Maria Montessori wrote that she predicted the 20th century would be the century of the child.[14]

Havelock Ellis wrote positively on her studies of human sexuality.

Key maintained that motherhood is so crucial to society that the government, rather than their husbands, should support mothers and their children. These ideas regarding state child support influenced social legislation in several countries.[13]

A substantial collection of Key's papers is at the Royal Library in Stockholm.[3]

In the 1890s, Key commissioned the Strand house designed by architect Yngve Rasmussen.[15] In the 1890s, it was "a centre for the politically radical intellectual and artistic avant-garde of Stockholm".[16] Key's house has become a foundation and tourist spot.[17]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Barnets århundrade at Project Runeberg

- ^ Ellen Key – Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Wilkinson, Lynn R. (2002). Twentieth-Century Swedish Writers Before World War II. Farmington Hills, Michigan: Gale. ISBN 978-0-7876-5261-6.

- ^ Ambjörnsson, Ronny, Ellen Key: en europeisk intellektuell, Bonnier, Stockholm, 2012

- ^ "Idunesen – vem var hon?" (in Swedish). 2014-02-09. Retrieved 2022-03-18.

- ^ "Ellen Karolina Sofia Key". Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon. Retrieved 2022-04-18.

- ^ Linder, Gurli. ""Mottagningar" och "salonger"". Stockholmskällan (in Swedish). Retrieved 2022-03-21.

- ^ Heggestad, Eva (8 March 2018). "Amalia Wilhelmina Fahlstedt". Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon (in Swedish). Retrieved 9 October 2024.

- ^ The Cambridge Chronicle, Cambridge, Massachusetts, October 19, 1912, p. 20

- ^ "The woman movement". New York Putnam. 1912.

- ^ From Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education. (Copyright UNESCO: International Bureau of Education 2000)

- ^ Borthwick, Mamah; Friedman, Alice T. (June 2002). "Frank Lloyd Wright and Feminism: Mamah Borthwick's Letters to Ellen Key". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 61 (2): 140–151. doi:10.2307/991836. JSTOR 991836. Archived from the original on 2018-11-04. Retrieved 2018-11-04.

- ^ a b The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. Copyright 2001-05 Columbia University Press.

- ^ Montessori, Maria (1972). The Secret of Childhood, New York, Ballantine Books.

- ^ Johamesson, Lena (January 1995). "Ellen Key, Mamah Bouton Borthwick and Frank Lloyd Wright. Notes on the historiography of non-existing history". NORA - Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research. 3 (2): 126–136. doi:10.1080/08038740.1995.9959681.

- ^ Johamesson, Lena (January 1995). "Ellen Key, Mamah Bouton Borthwick and Frank Lloyd Wright. Notes on the historiography of non-existing history". NORA - Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research. 3 (2): 126–136. doi:10.1080/08038740.1995.9959681.

- ^ "Ellen Key's Strand". Archived from the original on 29 May 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Ellen Karolina Sofia Key at Svenskt kvinnobiografiskt lexikon

- Lindholm, Elena; Åkerström, Ulla (eds.) (2020). Collective Motherliness in Europe (1890-1939): the Reception and Reformulation of Ellen Key's Ideas on Motherhood and Female Sexuality. Berlin: Peter Lang. ISBN 9783631819432

- Nyström-Hamilton, Louise (1913). Ellen Key, Her Life and Her Work. Translated by A. E. B. Fries. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons.

External links

[edit]- Works by Ellen Key at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ellen Key at the Internet Archive

- UNESCO paper on Ellen Key Archived 2013-11-05 at the Wayback Machine

- Ronny Ambjörnsson (2014) Ellen Key and the concept of Bildung Archived 2021-01-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Newspaper clippings about Ellen Key in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

.jpg/250px-Ellen_Key._Becker_&_Maass,_Berlin_(cropped).jpg)

.jpg/1541px-Ellen_Key._Becker_&_Maass,_Berlin_(cropped).jpg)