Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Selective breeding

View on Wikipedia| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

Selective breeding (also called artificial selection) is the process by which humans use animal breeding and plant breeding to selectively develop particular phenotypic traits (characteristics) by choosing which typically animal or plant males and females will sexually reproduce and have offspring together. Domesticated animals are known as breeds, normally bred by a professional breeder, while domesticated plants are known as varieties, cultigens, cultivars, or breeds.[1] Two purebred animals of different breeds produce a crossbreed, and crossbred plants are called hybrids. Flowers, vegetables and fruit-trees may be bred by amateurs and commercial or non-commercial professionals: major crops are usually the provenance of the professionals.

In animal breeding artificial selection is often combined with techniques such as inbreeding, linebreeding, and outcrossing. In plant breeding, similar methods are used. Charles Darwin discussed how selective breeding had been successful in producing change over time in his 1859 book, On the Origin of Species. Its first chapter discusses selective breeding and domestication of such animals as pigeons, cats, cattle, and dogs. Darwin used artificial selection as an analogy to propose and explain the theory of natural selection but distinguished the latter from the former as a separate process that is non-directed.[2][3][4]

The deliberate exploitation of selective breeding to produce desired results has become very common in agriculture and experimental biology.

Selective breeding can be unintentional, for example, resulting from the process of human cultivation; and it may also produce unintended – desirable or undesirable – results. For example, in some grains, an increase in seed size may have resulted from certain ploughing practices rather than from the intentional selection of larger seeds. Most likely, there has been an interdependence between natural and artificial factors that have resulted in plant domestication.[5]

History

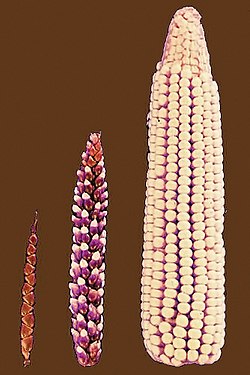

[edit]Selective breeding of both plants and animals has been practiced since prehistory; key species such as wheat, rice, and dogs have been significantly different from their wild ancestors for millennia, and maize, which required especially large changes from teosinte, its wild form, was selectively bred in Mesoamerica. Selective breeding was practiced by the Romans.[6] Treatises as much as 2,000 years old give advice on selecting animals for different purposes, and these ancient works cite still older authorities, such as Mago the Carthaginian.[7] The notion of selective breeding was later expressed by the polymath Abu Rayhan Biruni in the 11th century. He noted the idea in his book titled India, which included various examples.[8]

The agriculturist selects his corn, letting grow as much as he requires, and tearing out the remainder. The forester leaves those branches which he perceives to be excellent, whilst he cuts away all others. The bees kill those of their kind who only eat, but do not work in their beehive.

— Abu Rayhan Biruni, India

Selective breeding was established as a scientific practice by Robert Bakewell during the British Agricultural Revolution in the 18th century. Arguably, his most important breeding program was with sheep. Using native stock, he was able to quickly select for large, yet fine-boned sheep, with long, lustrous wool. The Lincoln Longwool was improved by Bakewell, and in turn the Lincoln was used to develop the subsequent breed, named the New (or Dishley) Leicester. It was hornless and had a square, meaty body with straight top lines.[9]

These sheep were exported widely, including to Australia and North America, and have contributed to numerous modern breeds, despite the fact that they fell quickly out of favor as market preferences in meat and textiles changed. Bloodlines of these original New Leicesters survive today as the English Leicester (or Leicester Longwool), which is primarily kept for wool production.

Bakewell was also the first to breed cattle to be used primarily for beef. Previously, cattle were first and foremost kept for pulling ploughs as oxen,[10] but he crossed long-horned heifers and a Westmoreland bull to eventually create the Dishley Longhorn. As more and more farmers followed his lead, farm animals increased dramatically in size and quality. In 1700, the average weight of a bull sold for slaughter was 370 pounds (168 kg). By 1786, that weight had more than doubled to 840 pounds (381 kg). However, after his death, the Dishley Longhorn was replaced with short-horn versions.

He also bred the Improved Black Cart horse, which later became the Shire horse.

Charles Darwin coined the term 'selective breeding'; he was interested in the process as an illustration of his proposed wider process of natural selection. Darwin noted that many domesticated animals and plants had special properties that were developed by intentional animal and plant breeding from individuals that showed desirable characteristics, and discouraging the breeding of individuals with less desirable characteristics.

Darwin used the term "artificial selection" twice in the 1859 first edition of his work On the Origin of Species, in Chapter IV: Natural Selection, and in Chapter VI: Difficulties on Theory:

Slow though the process of selection may be, if feeble man can do much by his powers of artificial selection, I can see no limit to the amount of change, to the beauty and infinite complexity of the co-adaptations between all organic beings, one with another and with their physical conditions of life, which may be effected in the long course of time by nature's power of selection.[11]

— Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

We are profoundly ignorant of the causes producing slight and unimportant variations; and we are immediately made conscious of this by reflecting on the differences in the breeds of our domesticated animals in different countries,—more especially in the less civilized countries where there has been but little artificial selection.[12]

— Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species

Animal breeding

[edit]Animals with homogeneous appearance, behavior, and other characteristics are known as particular breeds or pure breeds, and they are bred through culling animals with particular traits and selecting for further breeding those with other traits. Purebred animals belong to a single, recognizable breed, and purebreds with recorded lineage are called pedigreed. Crossbreeds are a mix of two purebreds, whereas mixed breeds are a mix of several breeds, often unknown. Animal breeding begins with breeding stock, a group of animals used for the purpose of planned breeding. When individuals are looking to breed animals, they look for certain valuable traits in purebred stock for a certain purpose, or may intend to use some type of crossbreeding to produce a new type of stock with different and presumably superior abilities in a given area of endeavor. For example, to breed chickens, a breeder typically intends to receive eggs, meat, and new, young birds for further reproduction. Thus, the breeder has to study different breeds and types of chickens and analyze what can be expected from a certain set of characteristics before he or she starts breeding them. Therefore, when purchasing initial breeding stock, the breeder seeks a group of birds that will most closely fit the purpose intended.

Purebred breeding aims to establish and maintain stable traits, that animals will pass to the next generation. By "breeding the best to the best," employing a certain degree of inbreeding, considerable culling, and selection for "superior" qualities, one could develop a bloodline superior in certain respects to the original base stock. Such animals can be recorded with a breed registry, the organization that maintains pedigrees and/or stud books. However, single-trait breeding, breeding for only one trait over all others, can be problematic.[13] In one case mentioned by the animal behaviorist Temple Grandin, roosters bred for fast growth or heavy muscles did not know how to perform typical rooster courtship dances, which alienated the roosters from hens and led the roosters to kill the hens after mating with them.[13] A Soviet attempt to breed lab rats with higher intelligence led to cases of neurosis severe enough to make the animals incapable of any problem solving unless drugs like phenazepam were used.[14]

The observable phenomenon of hybrid vigor stands in contrast to the notion of breed purity. However, on the other hand, indiscriminate breeding of crossbred or hybrid animals may also result in degradation of quality. Studies in evolutionary physiology, behavioral genetics, and other areas of organismal biology have also made use of deliberate selective breeding, though longer generation times and greater difficulty in breeding can make these projects challenging in such vertebrates as house mice.[15][16][17]

Plant breeding

[edit]

The process of plant breeding has been used for thousands of years, and began with the domestication of wild plants into uniform and predictable agricultural cultigens. These high-yielding varieties have been particularly important in agriculture. As crops improved, humans were able to move from hunter-gatherer style living to a mix of hunter-gatherer and agriculture practices.[18] Although these higher yielding plants were derived from an extremely primitive version of plant breeding, this form of agriculture was an investment that the people who grew them were planting then could have a more varied diet. This meant that they did not completely stop their hunting and gathering immediately but instead over time transitioned and ultimately favored agriculture.[19] Originally this was due to humans not wanting to risk using all their time and resources for their crops just to fail. Which was promptly called play farming due to the idea of "farmers" experimenting with agriculture.[19] In addition, the ability for humans to stay within one place for food and create permanent settlements made the process move along faster.[20] During this transitional period, crops began to acclimate and evolve with humans encouraging humans to invest further into crops. Over time this reliance on plant breeding has created problems, as highlighted by the book Botany of Desire where Michael Pollan shows the connection between basic human desires through four different plants: apples for sweetness, tulips for beauty, cannabis for intoxication, and potatoes for control. In a form of coevolution humans have influenced these plants as much as the plants have influenced the people that consume them[21]

Selective plant breeding is also used in research to produce transgenic animals that breed "true" (i.e., are homozygous) for artificially inserted or deleted genes.[22]

Selective breeding in aquaculture

[edit]Selective breeding in aquaculture holds high potential for the genetic improvement of fish and shellfish for the process of production. Unlike terrestrial livestock, the potential benefits of selective breeding in aquaculture were not realized until recently. This is because high mortality led to the selection of only a few broodstock, causing inbreeding depression, which then forced the use of wild broodstock. This was evident in selective breeding programs for growth rate, which resulted in slow growth and high mortality.[23]

Control of the reproduction cycle was one of the main reasons as it is a requisite for selective breeding programs. Artificial reproduction was not achieved because of the difficulties in hatching or feeding some farmed species such as eel and yellowtail farming.[24] A suspected reason associated with the late realization of success in selective breeding programs in aquaculture was the education of the concerned people – researchers, advisory personnel and fish farmers. The education of fish biologists paid less attention to quantitative genetics and breeding plans.[25]

Another was the failure of documentation of the genetic gains in successive generations. This in turn led to failure in quantifying economic benefits that successful selective breeding programs produce. Documentation of the genetic changes was considered important as they help in fine tuning further selection schemes.[23]

Quality traits in aquaculture

[edit]Aquaculture species are reared for particular traits such as growth rate, survival rate, meat quality, resistance to diseases, age at sexual maturation, fecundity, shell traits like shell size, shell color, etc.

- Growth rate – growth rate is normally measured as either body weight or body length. This trait is of great economic importance for all aquaculture species as faster growth rate speeds up the turnover of production.[25] Improved growth rates show that farmed animals utilize their feed more efficiently through a positive correlated response.[24]

- Survival rate – survival rate may take into account the degrees of resistance to diseases.[24] This may also see the stress response as fish under stress are highly vulnerable to diseases.[25] The stress fish experience could be of biological, chemical or environmental influence.

- Meat quality – the quality of fish is of great economic importance in the market. Fish quality usually takes into account size, meatiness, and percentage of fat, color of flesh, taste, shape of the body, ideal oil and omega-3 content.[24][26]

- Age at sexual maturation – The age of maturity in aquaculture species is another very important attribute for farmers as during early maturation the species divert all their energy to gonad production affecting growth and meat production and are more susceptible to health problems (Gjerde 1986).

- Fecundity – As the fecundity in fish and shellfish is usually high it is not considered as a major trait for improvement. However, selective breeding practices may consider the size of the egg and correlate it with survival and early growth rate.[24]

Finfish response to selection

[edit]Salmonids

[edit]Gjedrem (1979) showed that selection of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) led to an increase in body weight by 30% per generation. A comparative study on the performance of select Atlantic salmon with wild fish was conducted by AKVAFORSK Genetics Centre in Norway. The traits, for which the selection was done included growth rate, feed consumption, protein retention, energy retention, and feed conversion efficiency. Selected fish had a twice better growth rate, a 40% higher feed intake, and an increased protein and energy retention. This led to an overall 20% better Fed Conversion Efficiency as compared to the wild stock.[27] Atlantic salmon have also been selected for resistance to bacterial and viral diseases. Selection was done to check resistance to Infectious Pancreatic Necrosis Virus (IPNV). The results showed 66.6% mortality for low-resistant species whereas the high-resistant species showed 29.3% mortality compared to wild species.[28]

Rainbow trout (S. gairdneri) was reported to show large improvements in growth rate after 7–10 generations of selection.[29] Kincaid et al. (1977) showed that growth gains by 30% could be achieved by selectively breeding rainbow trout for three generations.[30] A 7% increase in growth was recorded per generation for rainbow trout by Kause et al. (2005).[31]

In Japan, high resistance to IPNV in rainbow trout has been achieved by selectively breeding the stock. Resistant strains were found to have an average mortality of 4.3% whereas 96.1% mortality was observed in a highly sensitive strain.[32]

Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) increase in weight was found to be more than 60% after four generations of selective breeding.[33] In Chile, Neira et al. (2006) conducted experiments on early spawning dates in coho salmon. After selectively breeding the fish for four generations, spawning dates were 13–15 days earlier.[34]

Cyprinids

Selective breeding programs for the Common carp (Cyprinus carpio) include improvement in growth, shape and resistance to disease. Experiments carried out in the USSR used crossings of broodstocks to increase genetic diversity and then selected the species for traits like growth rate, exterior traits and viability, and/or adaptation to environmental conditions like variations in temperature. Kirpichnikov et al. (1974)[35] and Babouchkine (1987)[36] selected carp for fast growth and tolerance to cold, the Ropsha carp. The results showed a 30–40% to 77.4% improvement of cold tolerance but did not provide any data for growth rate. An increase in growth rate was observed in the second generation in Vietnam.[37] Moav and Wohlfarth (1976) showed positive results when selecting for slower growth for three generations compared to selecting for faster growth. Schaperclaus (1962) showed resistance to the dropsy disease wherein selected lines suffered low mortality (11.5%) compared to unselected (57%).[38]

Channel Catfish

[edit]Growth was seen to increase by 12–20% in selectively bred Iictalurus punctatus.[39] More recently, the response of the Channel Catfish to selection for improved growth rate was found to be approximately 80%, that is, an average of 13% per generation.

Shellfish response to selection

[edit]Oysters

[edit]Selection for live weight of Pacific oysters showed improvements ranging from 0.4% to 25.6% compared to the wild stock.[40] Sydney-rock oysters (Saccostrea commercialis) showed a 4% increase after one generation and a 15% increase after two generations.[41][42] Chilean oysters (Ostrea chilensis), selected for improvement in live weight and shell length showed a 10–13% gain in one generation. Bonamia ostrea is a protistan parasite that causes catastrophic losses (nearly 98%) in European flat oyster Ostrea edulis L. This protistan parasite is endemic to three oyster-regions in Europe. Selective breeding programs show that O. edulis susceptibility to the infection differs across oyster strains in Europe. A study carried out by Culloty et al. showed that 'Rossmore' oysters in Cork harbour, Ireland had better resistance compared to other Irish strains. A selective breeding program at Cork harbour uses broodstock from 3– to 4-year-old survivors and is further controlled until a viable percentage reaches market size.[43][44]

Over the years 'Rossmore' oysters have shown to develop lower prevalence of B. ostreae infection and percentage mortality. Ragone Calvo et al. (2003) selectively bred the eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, for resistance against co-occurring parasites Haplosporidium nelson (MSX) and Perkinsus marinus (Dermo). They achieved dual resistance to the disease in four generations of selective breeding. The oysters showed higher growth and survival rates and low susceptibility to the infections. At the end of the experiment, artificially selected C. virginica showed a 34–48% higher survival rate.[45]

Penaeid shrimps

[edit]Selection for growth in Penaeid shrimps yielded successful results. A selective breeding program for Litopenaeus stylirostris saw an 18% increase in growth after the fourth generation and 21% growth after the fifth generation.[46] Marsupenaeus japonicas showed a 10.7% increase in growth after the first generation.[47] Argue et al. (2002) conducted a selective breeding program on the Pacific White Shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei at The Oceanic Institute, Waimanalo, USA from 1995 to 1998. They reported significant responses to selection compared to the unselected control shrimps. After one generation, a 21% increase was observed in growth and 18.4% increase in survival to TSV.[48] The Taura Syndrome Virus (TSV) causes mortalities of 70% or more in shrimps. C.I. Oceanos S.A. in Colombia selected the survivors of the disease from infected ponds and used them as parents for the next generation. They achieved satisfying results in two or three generations wherein survival rates approached levels before the outbreak of the disease.[49] The resulting heavy losses (up to 90%) caused by Infectious hypodermal and haematopoietic necrosis virus (IHHNV) caused a number of shrimp farming industries started to selectively breed shrimps resistant to this disease. Successful outcomes led to development of Super Shrimp, a selected line of L. stylirostris that is resistant to IHHNV infection. Tang et al. (2000) confirmed this by showing no mortalities in IHHNV- challenged Super Shrimp post larvae and juveniles.[50]

Aquatic species versus terrestrial livestock

[edit]Selective breeding programs for aquatic species provide better outcomes compared to terrestrial livestock. This higher response to selection of aquatic farmed species can be attributed to the following:

- High fecundity in both sexes fish and shellfish enabling higher selection intensity.

- Large phenotypic and genetic variation in the selected traits.

Selective breeding in aquaculture provide remarkable economic benefits to the industry, the primary one being that it reduces production costs due to faster turnover rates. When selective breeding is carried out, some characteristics are lost for others that may suit a specific environment or situation.[51] This is because of faster growth rates, decreased maintenance rates, increased energy and protein retention, and better feed efficiency.[23] Applying genetic improvement programs to aquaculture species will increase their productivity. Thus allowing them to meet the increasing demands of growing populations. Conversely, selective breeding within aquaculture can create problems within the biodiversity of both stock and wild fish, which can hurt the industry down the road. Although there is great potential to improve aquaculture due to the current lack of domestication, it is essential that the genetic diversity of the fish are preserved through proper genetic management, as we domesticate these species.[52] It is not uncommon for fish to escape the nets or pens that they are kept in, especially in mass. If these fish are farmed in areas they are not native to they may be able to establish themselves and outcompete native populations of fish, and cause ecological harm as an invasive species.[53] Furthermore, if they are in areas where the fish being farmed are native too their genetics are selectively bred rather than being wild. These farmed fish could breed with the natives which could be problematic In the sense that they would have been bred for consumption rather than by chance. Resulting in an overall decrease in genetic diversity and rendering local fish populations less fit for survival.[53] If proper management is not taking place then the economic benefits and the diversity of the fish species will falter.[52]

Advantages and disadvantages

[edit]Selective breeding is a direct way to determine if a specific trait can evolve in response to selection. A single-generation method of breeding is not as accurate or direct. The process is also more practical and easier to understand than sibling analysis. Selective breeding is better for traits such as physiology and behavior that are hard to measure because it requires fewer individuals to test than single-generation testing.

However, there are disadvantages to this process. This is because a single experiment done in selective breeding cannot be used to assess an entire group of genetic variances, individual experiments must be done for every individual trait. Also, due to the necessity of selective breeding experiments to require maintaining the organisms tested in a lab or greenhouse, it is impractical to use this breeding method on many organisms. Controlled mating instances are difficult to carry out in this case and this is a necessary component of selective breeding.[54]

Additionally, selective breeding can lead to a variety of issues including reduction of genetic diversity or physical problems. The process of selective breeding can create physical issues for plants or animals such as dogs selectively bred for extremely small sizes dislocating their kneecaps at a much more frequent rate then other dogs.[55] An example in the plant world is the Lenape potatoes were selectively bred for their disease or pest resistance which was attributed to their high levels of toxic glycoalkaloid solanine which are usually present only in small amounts in potatoes fit for human consumption.[56] When genetic diversity is lost it can also allow for populations to lack genetic alternatives to adapt to events. This becomes an issue of biodiversity, because attributes are so wide-spread they can result in mass epidemics. As seen in the Southern Corn leaf-blight epidemic of 1970 that wiped out 15% of the United States corn crop due to the wide use of a type of Texan corn strain that was artificially selected due to having sterile pollen to make farming easier. At the same time it was more vulnerable to Southern Corn leaf-blight.[57][58]

See also

[edit]- Animal breeding

- Animal husbandry

- Breed registry

- Breeding back

- Captive breeding

- Culling

- Eugenics

- Experimental evolution

- Gene pool

- Genetic engineering

- Genomics of domestication

- Inbreeding

- Marker-assisted selection

- Mutation breeding

- Natural selection

- Plant breeding

- Potsdam Giants

- Quantitative genetics

- Serial passage

- Selection limits

- Selection methods in plant breeding based on mode of reproduction

- Selective Breeding and the Birth of Philosophy

References

[edit]- ^ https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/breed (Noun definition 1)

- ^ Darwin, Charles (2008) [1859]. On the Origin of Species By Means of Natural Selection or The Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (Reissue ed.). New York: Bantam Books. pp. 9–132. ISBN 978-0553214635.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1996) [1986]. The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe Without Design. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 7–11. ISBN 978-0393351491.

- ^ Boehm, Christopher (2012). Moral Origins: The Evolution of Virtue, Altruism, and Shame. New York: Basic Books. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0465020485.

- ^ Purugganan, M. D.; Fuller, D. Q. (2009). "The nature of selection during plant domestication". Nature. 457 (7231): 843–8. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..843P. doi:10.1038/nature07895. PMID 19212403. S2CID 205216444.

- ^ Buffum, Burt C. (2008). Arid Agriculture; A Hand-Book for the Western Farmer and Stockman. Read Books. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4086-6710-1.

- ^ Lush, Jay L. (2008). Animal Breeding Plans. Orchard Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-4437-8451-1.

- ^ Wilczynski, J. Z. (1959). "On the Presumed Darwinism of Alberuni Eight Hundred Years before Darwin". Isis. 50 (4): 459–466. doi:10.1086/348801. S2CID 143086988.

- ^ "Robert Bakewell (1725–1795)". BBC History. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ^ Bean, John (2016). Trail of the Viking Finger. Troubador Publishing. p. 114. ISBN 978-1785893056.

- ^ Darwin, p. 109

- ^ Darwin, pp. 197–198

- ^ a b Grandin, Temple; Johnson, Catherine (2005). Animals in Translation. New York, New York: Scribner. pp. 69–71. ISBN 978-0-7432-4769-6.

- ^ "Жили-были крысы". Archived from the original on 9 August 2014. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ^ Swallow, JG; Garland, T. Jr. (2005). "Selection experiments as a tool in evolutionary and comparative physiology: insights into complex traits—an introduction to the symposium" (PDF). Integr Comp Biol. 45 (3): 387–390. doi:10.1093/icb/45.3.387. PMID 21676784. S2CID 2305227.

- ^ Garland, T. Jr. (2003). Selection experiments: an under-utilized tool in biomechanics and organismal biology. Ch. 3, Vertebrate Biomechanics and Evolution ed. Bels VL, Gasc JP, Casinos A. PDF

- ^ Garland, T. Jr., Rose MR, eds. (2009). Experimental Evolution: Concepts, Methods, and Applications of Selection Experiments. University of California Press, Berkeley, California.

- ^ "The Development of Agriculture". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ a b Deresiewicz, William (18 October 2021). "Human History Gets a Rewrite". The Atlantic. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ "Hunter-Gatherer Culture". education.nationalgeographic.org. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Pollan, Michael (2002). The botany of desire: a plant's-eye view of the world. Random House trade paperbacks (Paperback ed.). New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 978-0-375-76039-6.

- ^ Jain, H. K.; Kharkwal, M. C. (2004). Plant breeding – Mendelian to molecular approaches. Boston, London, Dordecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4020-1981-4.

- ^ a b c Gjedrem, T & Baranski, M. (2009). Selective breeding in Aquaculture: An Introduction. 1st Edition. Springer. ISBN 978-90-481-2772-6

- ^ a b c d e Gjedrem, T. (1985). "Improvement of productivity through breeding schemes". GeoJournal. 10 (3): 233–241. Bibcode:1985GeoJo..10..233G. doi:10.1007/BF00462124. S2CID 154519652.

- ^ a b c Gjedrem, T. (1983). "Genetic variation in quantitative traits and selective breeding in fish and shellfish". Aquaculture. 33 (1–4): 51–72. Bibcode:1983Aquac..33...51G. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(83)90386-1.

- ^ Joshi, Rajesh; Woolliams, John; Meuwissen, Theo MJ (January 2018). "Maternal, dominance and additive genetic effects in Nile tilapia; influence on growth, fillet yield and body size traits". Heredity. 120 (5): 452–462. Bibcode:2018Hered.120..452J. doi:10.1038/s41437-017-0046-x. PMC 5889400. PMID 29335620.

- ^ Thodesen, J. R.; Grisdale-Helland, B.; Helland, S. L. J.; Gjerde, B. (1999). "Feed intake, growth and feed utilization of offspring from wild and selected Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar)". Aquaculture. 180 (3–4): 237–246. Bibcode:1999Aquac.180..237T. doi:10.1016/s0044-8486(99)00204-5.

- ^ Storset, A.; Strand, C.; Wetten, M.; Kjøglum, S.; Ramstad, A. (2007). "Response to selection for resistance against infectious pancreatic necrosis in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.)". Aquaculture. 272: S62 – S68. Bibcode:2007Aquac.272..S62S. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2007.08.011.

- ^ Donaldson, L. R.; Olson, P. R. (1957). "Development of Rainbow Trout Brood Stock by Selective Breeding". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 85: 93–101. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1955)85[93:dortbs]2.0.co;2.

- ^ Kincaid, H. L.; Bridges, W. R.; von Limbach, B. (1977). "Three Generations of Selection for Growth Rate in Fall-Spawning Rainbow Trout". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 106 (6): 621–628. Bibcode:1977TrAFS.106..621K. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1977)106<621:tgosfg>2.0.co;2.

- ^ Kause, A.; Ritola, O.; Paananen, T.; Wahlroos, H.; Mäntysaari, E. A. (2005). "Genetic trends in growth, sexual maturity and skeletal deformations, and rate of inbreeding in a breeding programme for rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss)". Aquaculture. 247 (1–4): 177–187. Bibcode:2005Aquac.247..177K. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2005.02.023.

- ^ Okamoto, N.; Tayama, T.; Kawanobe, M.; Fujiki, N.; Yasuda, Y.; Sano, T. (1993). "Resistance of a rainbow trout strain to infectious pancreatic necrosis". Aquaculture. 117 (1–2): 71–76. Bibcode:1993Aquac.117...71O. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(93)90124-h.

- ^ Hershberger, W. K.; Myers, J. M.; Iwamoto, R. N.; McAuley, W. C.; Saxton, A. M. (1990). "Genetic changes in the growth of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) in marine net-pens, produced by ten years of selection". Aquaculture. 85 (1–4): 187–197. Bibcode:1990Aquac..85..187H. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(90)90018-i.

- ^ Neira, R.; Díaz, N. F.; Gall, G. A. E.; Gallardo, J. A.; Lhorente, J. P.; Alert, A. (2006). "Genetic improvement in coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch). II: Selection response for early spawning date". Aquaculture. 257 (1–4): 1–8. Bibcode:2006Aquac.257....1N. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.03.001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2020. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- ^ Kirpichnikov, V. S.; Ilyasov, I.; Shart, L. A.; Vikhman, A. A.; Ganchenko, M. V.; Ostashevsky, A. L.; Simonov, V. M.; Tikhonov, G. F.; Tjurin, V. V. (1993). "Selection of Krasnodar common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) for resistance to dropsy: Principal results and prospects". Genetics in Aquaculture. p. 7. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-81527-9.50006-3. ISBN 9780444815279.

- ^ Babouchkine, Y.P., 1987. La sélection d'une carpe résistant à l'hiver. In: Tiews, K. (Ed.), Proceedings ofWorld Symposium on Selection, Hybridization, and Genetic Engineering in Aquaculture, Bordeaux 27–30 May 1986, vol. 1. HeenemannVerlagsgesellschaft mbH, Berlin, pp. 447–454.

- ^ Mai Thien Tran; Cong Thang Nguyen (1993). "Selection of common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.) in Vietnam". Aquaculture. 111 (1–4): 301–302. Bibcode:1993Aquac.111..301M. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(93)90064-6.

- ^ Moav, R; Wohlfarth, G (1976). "Two-way selection for growth rate in the common carp (Cyprinus carpio L.)". Genetics. 82 (1): 83–101. doi:10.1093/genetics/82.1.83. PMC 1213447. PMID 1248737.

- ^ Bondari, K. (1983). "Response to bidirectional selection for body weight in channel catfish". Aquaculture. 33 (1–4): 73–81. Bibcode:1983Aquac..33...73B. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(83)90387-3.

- ^ Langdon, C.; Evans, F.; Jacobson, D.; Blouin, M. (2003). "Yields of cultured Pacific oysters Crassostrea gigas Thunberg improved after one generation of selection". Aquaculture. 220 (1–4): 227–244. Bibcode:2003Aquac.220..227L. doi:10.1016/s0044-8486(02)00621-x.

- ^ Nell, J. A.; Sheridan, A. K.; Smith, I. R. (1996). "Progress in a Sydney rock oyster, Saccostrea commercialis (Iredale and Roughley), breeding program". Aquaculture. 144 (4): 295–302. Bibcode:1996Aquac.144..295N. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(96)01328-2.

- ^ Nell, J. A.; Smith, I. R.; Sheridan, A. K. (1999). "Third generation evaluation of Sydney rock oyster Saccostrea commercialis (Iredale and Roughley) breeding lines". Aquaculture. 170 (3–4): 195–203. Bibcode:1999Aquac.170..195N. doi:10.1016/s0044-8486(98)00408-6.

- ^ Culloty, S. C.; Cronin, M. A.; Mulcahy, M. F. (2001). "An investigation into the relative resistance of Irish flat oysters Ostrea edulis L. to the parasite Bonamia ostreae". Aquaculture. 199 (3–4): 229–244. doi:10.1016/s0044-8486(01)00569-5.

- ^ Culloty, S. C.; Cronin, M. A.; Mulcahy, M. F. (2004). "Potential resistance of a number of populations of the oyster Ostrea edulis to the parasite Bonamia ostreae". Aquaculture. 237 (1–4): 41–58. Bibcode:2004Aquac.237...41C. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2004.04.007.

- ^ Ragone Calvo, L. M.; Calvo, G. W.; Burreson, E. M. (2003). "Dual disease resistance in a selectively bred eastern oyster, Crassostrea virginica, strain tested in Chesapeake Bay". Aquaculture. 220 (1–4): 69–87. Bibcode:2003Aquac.220...69R. doi:10.1016/s0044-8486(02)00399-x.

- ^ Goyard, E.; Patrois, J.; Reignon, J.-M.; Vanaa, V.; Dufour, R; Be (1999). "IFREMER's shrimp genetics program". Global Aquaculture Advocate. 2 (6): 26–28.

- ^ Hetzel, D. J. S.; Crocos, P. J.; Davis, G. P.; Moore, S. S.; Preston, N. C. (2000). "Response to selection and heritability for growth in the Kuruma prawn, Penaeus japonicus". Aquaculture. 181 (3–4): 215–223. Bibcode:2000Aquac.181..215H. doi:10.1016/S0044-8486(99)00237-9.

- ^ Argue, B. J.; Arce, S. M.; Lotz, J. M.; Moss, S. M. (2002). "Selective breeding of Pacific white shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei) for growth and resistance to Taura Syndrome Virus". Aquaculture. 204 (3–4): 447–460. Bibcode:2002Aquac.204..447A. doi:10.1016/s0044-8486(01)00830-4.

- ^ Cock, J.; Gitterle, T.; Salazar, M.; Rye, M. (2009). "Breeding for disease resistance of Penaeid shrimps". Aquaculture. 286 (1–2): 1–11. Bibcode:2009Aquac.286....1C. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.09.011.

- ^ Tang, K. F. J.; Durand, S. V.; White, B. L.; Redman, R. M.; Pantoja, C. R.; Lightner, D. V. (2000). "Postlarvae and juveniles of a selected line of Penaeus stylirostris are resistant to infectious hypodermal and hematopoietic necrosis virus infection". Aquaculture. 190 (3–4): 203–210. Bibcode:2000Aquac.190..203T. doi:10.1016/s0044-8486(00)00407-5.

- ^ "What Is the Main Idea of Overproduction in Natural Selection?". Sciencing. 30 July 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

- ^ a b Lind, Ce; Ponzoni, Rw; Nguyen, Nh; Khaw, Hl (August 2012). "Selective Breeding in Fish and Conservation of Genetic Resources for Aquaculture". Reproduction in Domestic Animals. 47 (s4): 255–263. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0531.2012.02084.x. ISSN 0936-6768. PMID 22827379.

- ^ a b "Prevent farmed fish escapes". Seafood Watch. Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ Conner, J. K. (2003). "Artificial Selection: A Powerful Tool for Ecologists". Ecology. 84 (7): 1650–1660. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(2003)084[1650:asaptf]2.0.co;2.

- ^ admin (16 September 2010). "Dogs That Changed The World ~ Selective Breeding Problems | Nature". Nature. Retrieved 29 January 2024.

- ^ Health, National Research Council (US) Committee on Identifying and Assessing Unintended Effects of Genetically Engineered Foods on Human (2004), "Unintended Effects from Breeding", Safety of Genetically Engineered Foods: Approaches to Assessing Unintended Health Effects, National Academies Press (US), retrieved 29 January 2024

- ^ Clarke, Robert Connell (1981). Marijuana Botany. Berkeley, Calif: And/Or Pr. ISBN 978-0-915904-45-7.

- ^ "Southern Corn Leaf Blight: A Story Worth Retelling". CSA News. 62 (8): 13. August 2017. Bibcode:2017CSAN...62S..13.. doi:10.2134/csa2017.62.0806. ISSN 1529-9163.

Bibliography

[edit]- Darwin, Charles (2004). The Origin of Species. London: CRW Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-904633-78-5.

Further reading

[edit]- FAO. 2007. The Global Plan of Action for Animal Genetic Resources and the Interlaken Declaration. Rome.

- FAO. 2015. The Second Report on the State of the World's Animal Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. Rome. Archived 18 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Gjerdem, B (1986). "Growth and reproduction in fish and shellfish". Aquaculture. 57 (1–4): 37–55. Bibcode:1986Aquac..57...37G. doi:10.1016/0044-8486(86)90179-1.

- Gjedrem, T (1979). "Selection for growth rate and domestication in Atlantic salmon". Zeitschrift für Tierzüchtung und Züchtungsbiologie. 96 (1–4): 56–59. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0388.1979.tb00199.x.

- Gjedrem, T. (1477). "Selective breeding to improve aquaculture production". World Aquaculture. 28: 33–45.

- Purugganan, Michael D.; Fuller, Dorian Q. (2009). "The nature of selection during plant domestication". Nature. 457 (7231): 843–848. Bibcode:2009Natur.457..843P. doi:10.1038/nature07895. PMID 19212403. S2CID 205216444.

- Schäperclaus, W. (1962). Traité de pisciculture en étang. Paris: Vigot Frères.

External links

[edit]Selective breeding

View on GrokipediaSelective breeding, also termed artificial selection, is the process by which humans deliberately mate plants or animals exhibiting desired heritable traits to produce offspring that more consistently display and enhance those characteristics across generations, thereby accelerating genetic changes aligned with human objectives such as improved yield, size, or utility.[1][2] This method contrasts with natural selection by substituting human choice for environmental pressures, enabling rapid adaptation of domesticated species to agricultural, industrial, or companion roles.[3] Practiced since approximately 9000 BCE, selective breeding underpinned the Neolithic domestication of staple crops like wheat and rice, as well as livestock such as cattle and dogs, transforming wild progenitors into highly productive forms that supported human population growth and civilization.[4] In plants, it has yielded diverse varieties, from high-yield maize kernels vastly larger than teosinte ancestors to multicolored carrots bred for nutritional content and aesthetics.[5] For animals, it produced the morphological diversity among dog breeds, from diminutive Chihuahuas to massive Great Danes, alongside enhanced traits like milk production in dairy cattle or rapid growth in broiler chickens.[6] These advancements have dramatically boosted global food security, with selective breeding contributing to exponential increases in crop and livestock productivity over millennia.[7] Despite its successes, selective breeding carries risks, including narrowed genetic diversity from intense focus on few traits, which can amplify deleterious recessive alleles and heighten vulnerability to diseases or environmental stresses, as observed in inbred livestock lines prone to fertility declines and skeletal disorders.[6][8] In companion animals like dogs, prioritizing extreme conformations—such as flattened faces in brachycephalic breeds—has led to chronic health issues including respiratory distress, hip dysplasia, and reduced lifespan, prompting debates on welfare standards in breeding practices.[8] Modern genomic tools now complement traditional selection to mitigate these pitfalls, enabling precise trait enhancement while preserving broader genetic health.[9]

Fundamentals

Definition and Core Principles

Selective breeding, also known as artificial selection, is the process by which humans intentionally select organisms possessing desirable traits for reproduction, thereby increasing the frequency and expression of those traits in subsequent generations.[2][3] This human-directed method contrasts with natural selection, as it substitutes deliberate choice for environmental pressures in determining which individuals contribute genes to the next generation.[5] The core principles of selective breeding rest on three foundational elements derived from population genetics: genetic variation, heritability, and differential reproduction. Genetic variation provides the raw material, arising from mutations, recombination, and gene flow, ensuring a range of phenotypic differences within a population upon which selection can operate.[10] Heritability quantifies the proportion of phenotypic variance attributable to genetic variance transmissible to offspring, typically estimated as , where is genetic variance and is total phenotypic variance; traits with higher heritability respond more predictably to selection.[11] Differential reproduction, imposed by human selection, favors individuals with superior trait values, generating a selection differential that translates into genetic gain over generations via the breeder's equation: , with as response to selection and as selection differential.[12] These principles enable cumulative improvement but are constrained by genetic limits, such as linkage disequilibrium or pleiotropy, where selection for one trait may inadvertently alter others.[1] Empirical evidence from long-term breeding programs, such as those in livestock yielding annual genetic gains of 1-5% in traits like milk yield, validates the efficacy of these mechanisms when applied systematically.[10]

.svg/232px-Mutation_and_selection_diagram_(2).svg.png)

.svg/1359px-Mutation_and_selection_diagram_(2).svg.png)