Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Epimer

View on WikipediaIn stereochemistry, an epimer is one of a pair of diastereomers.[1] The two epimers have opposite configuration at only one stereogenic center out of at least two.[2] All other stereogenic centers in the molecules are the same in each. Epimerization is the interconversion of one epimer to the other epimer.

Examples

[edit]The stereoisomers β-D-glucopyranose and β-D-mannopyranose are epimers because they differ only in the stereochemistry at the C-2 position. The hydroxy group in β-D-glucopyranose is equatorial (in the "plane" of the ring), while in β-D-mannopyranose the C-2 hydroxy group is axial (up from the "plane" of the ring). These two molecules are epimers but, because they are not mirror images of each other, are not enantiomers. (Enantiomers have the same name, but differ in D and L classification.) They are also not sugar anomers, since it is not the anomeric carbon involved in the stereochemistry. Similarly, β-D-glucopyranose and β-D-galactopyranose are epimers that differ at the C-4 position, with the former being equatorial and the latter being axial.

|

|

β-D-glucopyranose |

β-D-mannopyranose

|

In the case that the difference is the -OH groups on C-1, the anomeric carbon, such as in the case of α-D-glucopyranose and β-D-glucopyranose, the molecules are both epimers and anomers (as indicated by the α and β designation).[3]

|

|

α-D-glucopyranose |

β-D-glucopyranose

|

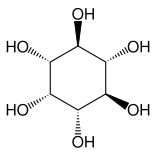

Other closely related compounds are epi-inositol and inositol, and lipoxin and epilipoxin.

|

|

|

|

epi-inositol

|

Inositol

|

Lipoxin

|

Epilipoxin

|

Doxorubicin and epirubicin are two epimers that are used as drugs.

|

Doxorubicin–epirubicin comparison

|

Epimerization

[edit]Epimerization is a chemical process where an epimer is converted to its diastereomeric counterpart.[1] It can happen in condensed tannins depolymerization reactions. Epimerization can be spontaneous (generally a slow process), or catalysed by enzymes, e.g. the epimerization between the sugars N-acetylglucosamine and N-acetylmannosamine, which is catalysed by renin-binding protein.

The penultimate step in Zhang & Trudell's classic epibatidine synthesis is an example of epimerization.[4] Pharmaceutical examples include epimerization of the erythro isomers of methylphenidate to the pharmacologically preferred and lower-energy threo isomers, and undesired in vivo epimerization of tesofensine to brasofensine.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Clayden, Jonathan; Greeves, Nick; Warren, Stuart (2012). Organic Chemistry (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 1112.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "Epimers". doi:10.1351/goldbook.E02167

- ^ Structure of the glucose molecule

- ^ Zhang, Chunming; Trudell, Mark L. (1996). "A Short and Efficient Total Synthesis of (±)-Epibatidine". The Journal of Organic Chemistry. 61 (20): 7189–7191. doi:10.1021/jo9608681. ISSN 0022-3263. PMID 11667626.

Epimer

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Terminology

Definition

An epimer is a type of stereoisomer classified as a diastereomer, characterized by having the opposite configuration at only one of two or more tetrahedral stereogenic centers, while maintaining identical configurations at all other stereogenic centers.[7] This distinguishes epimers from other stereoisomers, as they share the same molecular connectivity and differ solely in the spatial arrangement at a single chiral site among multiple present in the molecule.[1] Unlike enantiomers, which are nonsuperimposable mirror images differing in configuration at all chiral centers and exhibit identical physical properties except for optical rotation, epimers possess distinct physical and chemical properties due to their diastereomeric relationship.[8][9] For epimers to exist, the molecule must contain at least two chiral centers, as a single chiral center would only allow for enantiomers rather than this specific subtype of diastereomer.[10]Relation to Stereoisomers

Epimers are a specialized category within the broader class of stereoisomers, which encompass molecules sharing identical molecular formulas and connectivity but differing in the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms. Stereoisomers are primarily classified into enantiomers—non-superimposable mirror images that differ in configuration at all chiral centers—and diastereomers, which are stereoisomers lacking such mirror-image symmetry and differing in configuration at one or more, but not all, chiral centers. Epimers specifically denote diastereomers that vary in configuration at precisely one chiral center, positioning them as a subset of diastereomers in the stereochemical hierarchy.[11] This single-point difference distinguishes epimers from other stereoisomers, as it results in molecules with identical connectivity yet divergent spatial orientations at that stereocenter, leading to observable variations in physical and chemical properties. Unlike enantiomers, which exhibit identical NMR spectra, solubilities, and reactivities under achiral conditions, epimers display distinct NMR spectra due to their diastereomeric nature, as well as differences in reactivity influenced by the altered stereochemistry. Anomers constitute a particular subclass of epimers, arising from inversion at the anomeric carbon—the carbonyl-derived carbon in cyclic forms—highlighting how epimeric relationships can manifest in specific structural contexts.[12][13]| Stereoisomer Type | Definition | Chiral Center Difference | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enantiomers | Non-superimposable mirror images | All chiral centers | Identical physical properties (e.g., NMR, melting point) under achiral conditions; opposite optical rotation |

| Diastereomers | Stereoisomers that are not mirror images | Some but not all chiral centers | Distinct physical and chemical properties (e.g., different NMR spectra, reactivity) |

| Epimers | Subset of diastereomers differing at one chiral center | Exactly one chiral center | Distinct properties similar to diastereomers; specific to single stereocenter inversion |

| Anomers | Special case of epimers at the anomeric carbon in cyclic structures | Only the anomeric carbon | Distinct properties; interconvert via ring opening in solution |