Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Functional group

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2016) |

In organic chemistry, a functional group is any substituent or moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions regardless of the rest of the molecule's composition.[1][2] This enables systematic prediction of chemical reactions and behavior of chemical compounds and the design of chemical synthesis. The reactivity of a functional group can be modified by other functional groups nearby. Functional group interconversion can be used in retrosynthetic analysis to plan organic synthesis.

A functional group is a group of atoms in a molecule with distinctive chemical properties, regardless of the other atoms in the molecule. The atoms in a functional group are linked to each other and to the rest of the molecule by covalent bonds. For repeating units of polymers, functional groups attach to their nonpolar core of carbon atoms and thus add chemical character to carbon chains. Functional groups can also be charged, e.g. in carboxylate salts (−COO−), which turns the molecule into a polyatomic ion or a complex ion. Functional groups binding to a central atom in a coordination complex are called ligands. Complexation and solvation are also caused by specific interactions of functional groups. In the common rule of thumb "like dissolves like", it is the shared or mutually well-interacting functional groups which give rise to solubility. For example, sugar dissolves in water because both share the hydroxyl functional group (−OH) and hydroxyls interact strongly with each other. Plus, when functional groups are more electronegative than atoms they attach to, the functional groups will become polar, and the otherwise nonpolar molecules containing these functional groups become polar and so become soluble in some aqueous environment.

Combining the names of functional groups with the names of the parent alkanes generates what is termed a systematic nomenclature for naming organic compounds. In traditional nomenclature, the first carbon atom after the carbon that attaches to the functional group is called the alpha carbon; the second, beta carbon, the third, gamma carbon, etc. If there is another functional group at a carbon, it may be named with the Greek letter, e.g., the gamma-amine in gamma-aminobutyric acid is on the third carbon of the carbon chain attached to the carboxylic acid group. IUPAC conventions call for numeric labeling of the position, e.g. 4-aminobutanoic acid. In traditional names various qualifiers are used to label isomers, for example, isopropanol (IUPAC name: propan-2-ol) is an isomer of n-propanol (propan-1-ol). The term moiety has some overlap with the term "functional group". However, a moiety is an entire "half" of a molecule, which can be not only a single functional group, but also a larger unit consisting of multiple functional groups. For example, an "aryl moiety" may be any group containing an aromatic ring, regardless of how many functional groups the said aryl has.

Table of common functional groups

[edit]The following is a list of common functional groups.[3] In the formulas, the symbols R and R' usually denote an attached hydrogen, or a hydrocarbon side chain of any length, but may sometimes refer to any group of atoms.

Hydrocarbons

[edit]Hydrocarbons are a class of molecule that is defined by functional groups called hydrocarbyls that contain only carbon and hydrogen, but vary in the number and order of double bonds. Each one differs in type (and scope) of reactivity.

| Chemical class | Group | Formula | Structural Formula | Prefix | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkane | Alkyl | R(CH2)nH | alkyl- | -ane |  Ethane | |

| Alkene | Alkenyl | R2C=CR2 |

|

alkenyl- | -ene |  Ethylene (Ethene) |

| Alkyne | Alkynyl | RC≡CR′ | alkynyl- | -yne | Acetylene (Ethyne) | |

| Benzene derivative | Phenyl | RC6H5 RPh |

phenyl- | -benzene |  Cumene (Isopropylbenzene) |

There are also a large number of branched or ring alkanes that have specific names, e.g., tert-butyl, bornyl, cyclohexyl, etc. There are several functional groups that contain an alkene such as vinyl group, allyl group, or acrylic group. Hydrocarbons may form charged structures: positively charged carbocations or negative carbanions. Carbocations are often named -um. Examples are tropylium and triphenylmethyl cations and the cyclopentadienyl anion.

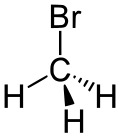

Groups containing halogens

[edit]Haloalkanes are a class of molecule that is defined by a carbon–halogen bond. This bond can be relatively weak (in the case of an iodoalkane) or quite stable (as in the case of a fluoroalkane). In general, with the exception of fluorinated compounds, haloalkanes readily undergo nucleophilic substitution reactions or elimination reactions. The substitution on the carbon, the acidity of an adjacent proton, the solvent conditions, etc. all can influence the outcome of the reactivity.

| Chemical class | Group | Formula | Structural formula | Prefix | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| haloalkane | halo | RX | halo- | alkyl halide | Chloroethane (Ethyl chloride) | |

| fluoroalkane | fluoro | RF | fluoro- | alkyl fluoride |  Fluoromethane (Methyl fluoride) | |

| chloroalkane | chloro | RCl | chloro- | alkyl chloride |  Chloromethane (Methyl chloride) | |

| bromoalkane | bromo | RBr | bromo- | alkyl bromide |  Bromomethane (Methyl bromide) | |

| iodoalkane | iodo | RI | iodo- | alkyl iodide |  Iodomethane (Methyl iodide) |

Groups containing oxygen

[edit]Compounds that contain C–O bonds each possess differing reactivity based upon the location and hybridization of the C–O bond, owing to the electron-withdrawing effect of sp-hybridized oxygen (carbonyl groups) and the donating effects of sp2-hybridized oxygen (alcohol groups).

| Chemical class | Group | Formula | Structural formula | Prefix | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol | Hydroxy | ROH | hydroxy- | -ol |  Methanol | |

| Ketone | Ketone | RCOR′ |

|

-oyl- (-COR′) or oxo- (=O) |

-one |  Butanone (Methyl ethyl ketone) |

| Aldehyde | Aldehyde | RCHO |

|

formyl- (-COH) or oxo- (=O) |

-al |  Acetaldehyde (Ethanal) |

| Acyl halide | Haloformyl | RCOX |

|

carbonofluoridoyl- carbonochloridoyl- carbonobromidoyl- carbonoiodidoyl- |

-oyl fluoride -oyl chloride -oyl bromide -oyl iodide |

Acetyl chloride (Ethanoyl chloride) |

| Carbonate | Carbonate ester | ROCOOR′ | (alkoxycarbonyl)oxy- | alkyl carbonate | Triphosgene (bis(trichloromethyl) carbonate) | |

| Carboxylate | Carboxylate | RCOO− |  |

carboxylato- | -oate | Sodium acetate (Sodium ethanoate) |

| Carboxylic acid | Carboxyl | RCOOH |

|

carboxy- | -oic acid |  Acetic acid (Ethanoic acid) |

| Ester | Carboalkoxy | RCOOR′ | alkanoyloxy- or alkoxycarbonyl |

alkyl alkanoate | Ethyl butyrate (Ethyl butanoate) | |

| Hydroperoxide | Hydroperoxy | ROOH | hydroperoxy- | alkyl hydroperoxide | tert-Butyl hydroperoxide | |

| Peroxide | Peroxy | ROOR′ | peroxy- | alkyl peroxide | Di-tert-butyl peroxide | |

| Ether | Ether | ROR′ | alkoxy- | alkyl ether | Diethyl ether (Ethoxyethane) | |

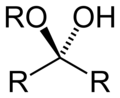

| Hemiacetal | Hemiacetal | R2CH(OR1)(OH) |

|

alkoxy -ol | -al alkyl hemiacetal | |

| Hemiketal | Hemiketal | RC(ORʺ)(OH)R′ |

|

alkoxy -ol | -one alkyl hemiketal | |

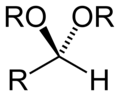

| Acetal | Acetal | RCH(OR′)(OR″) |

|

dialkoxy- | -al dialkyl acetal | |

| Ketal (or Acetal) | Ketal (or Acetal) | RC(OR″)(OR‴)R′ |

|

dialkoxy- | -one dialkyl ketal | |

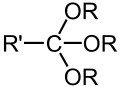

| Orthoester | Orthoester | RC(OR′)(OR″)(OR‴) |

|

trialkoxy- | ||

| Heterocycle (if cyclic) |

Methylenedioxy | (–OCH2O–) | methylenedioxy- | -dioxole |  1,2-Methylenedioxybenzene (1,3-Benzodioxole) | |

| Orthocarbonate ester | Orthocarbonate ester | C(OR)(OR′)(OR″)(OR‴) | tetralkoxy- | tetraalkyl orthocarbonate |  Tetramethoxymethane | |

| Organic acid anhydride | Carboxylic anhydride | R1(CO)O(CO)R2 | anhydride | Butyric anhydride |

Groups containing nitrogen

[edit]Compounds that contain nitrogen in this category may contain C-O bonds, such as in the case of amides.

| Chemical class | Group | Formula | Structural formula | Prefix | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amide | Carboxamide | RCONR'R" |

|

carboxamido- or carbamoyl- |

-amide |  Acetamide (Ethanamide) |

| Amidine | Amidine | R4C(NR1)(NR2R3) |

|

amidino- | -amidine |  acetamidine acetamidine

(acetimidamide) |

| Guanidine | Guanidine | RNC(NR2)2) |

|

Guanidin- | -Guanidine | Guanidinopropionic acid |

| Amines | Primary amine | RNH2 | amino- | -amine |  Methylamine (Methanamine) | |

| Secondary amine | R'R"NH |

|

amino- | -amine | Dimethylamine | |

| Tertiary amine | R3N |

|

amino- | -amine |  Trimethylamine | |

| 4° ammonium ion | R4N+ |

|

ammonio- | -ammonium |  Choline | |

| Hydrazone | R'R"CN2H2 |

|

hydrazino- | -hydrazine |  Benzophenone | |

| Imine | Primary ketimine | RC(=NH)R' |

|

imino- | -imine | |

| Secondary ketimine | RC(=NR)R' |

|

imino- | -imine | ||

| Primary aldimine | RC(=NH)H |

|

imino- | -imine | Ethanimine | |

| Secondary aldimine | RC(=NR')H |

|

imino- | -imine | ||

| Imide | Imide | (RCO)2NR' |

|

imido- | -imide |  Succinimide (Pyrrolidine-2,5-dione) |

| Azide | Azide | RN3 | azido- | alkyl azide |  Phenyl azide (Azidobenzene) | |

| Azo compound | Azo (Diimide) |

RN2R' | azo- | -diazene |  Methyl orange (p-dimethylamino-azobenzenesulfonic acid) | |

| Cyanates | Cyanate | ROCN | cyanato- | alkyl cyanate | Methyl cyanate | |

| Isocyanate | RNCO | isocyanato- | alkyl isocyanate | Methyl isocyanate | ||

| Nitrate | Nitrate | RONO2 | nitrooxy-, nitroxy- |

alkyl nitrate |

Amyl nitrate (1-nitrooxypentane) | |

| Nitrile | Nitrile | RCN | cyano- | alkanenitrile alkyl cyanide |

Benzonitrile (Phenyl cyanide) | |

| Isonitrile | RNC | isocyano- | alkaneisonitrile alkyl isocyanide |

Methyl isocyanide | ||

| Nitrite | Nitrosooxy | RONO | nitrosooxy- |

alkyl nitrite |

Isoamyl nitrite (3-methyl-1-nitrosooxybutane) | |

| Nitro compound | Nitro | RNO2 |

|

nitro- |  Nitromethane | |

| Nitroso compound | Nitroso | RNO | nitroso- (Nitrosyl-) | Nitrosobenzene | ||

| Oxime | Oxime | RCH=NOH |

|

Oxime |  Acetone oxime (2-Propanone oxime) | |

| Pyridine derivative | Pyridyl | RC5H4N |

4-pyridyl 3-pyridyl 2-pyridyl |

-pyridine |  Nicotine | |

| Carbamate ester | Carbamate | RO(C=O)NR2 |

|

(-carbamoyl)oxy- | -carbamate | Chlorpropham (Isopropyl (3-chlorophenyl)carbamate) |

Groups containing sulfur

[edit]Compounds that contain sulfur exhibit unique chemistry due to sulfur's ability to form more bonds than oxygen, its lighter analogue on the periodic table. Substitutive nomenclature (marked as prefix in table) is preferred over functional class nomenclature (marked as suffix in table) for sulfides, disulfides, sulfoxides and sulfones.

| Chemical class | Group | Formula | Structural formula | Prefix | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thiol | Sulfhydryl | RSH | sulfanyl- (-SH) |

-thiol | Ethanethiol | |

| Sulfide (Thioether) |

Sulfide | RSR' | substituent sulfanyl- (-SR') |

di(substituent) sulfide | (Methylsulfanyl)methane (prefix) or Dimethyl sulfide (suffix) | |

| Disulfide | Disulfide | RSSR' | substituent disulfanyl- (-SSR') |

di(substituent) disulfide | (Methyldisulfanyl)methane (prefix) or Dimethyl disulfide (suffix) | |

| Sulfoxide | Sulfinyl | RSOR' |

|

-sulfinyl- (-SOR') |

di(substituent) sulfoxide |  (Methanesulfinyl)methane (prefix) or Dimethyl sulfoxide (suffix) |

| Sulfone | Sulfonyl | RSO2R' |

|

-sulfonyl- (-SO2R') |

di(substituent) sulfone | (Methanesulfonyl)methane (prefix) or Dimethyl sulfone (suffix) |

| Sulfinic acid | Sulfino | RSO2H |

|

sulfino- (-SO2H) |

-sulfinic acid | 2-Aminoethanesulfinic acid |

| Sulfonic acid | Sulfo | RSO3H |

|

sulfo- (-SO3H) |

-sulfonic acid |  Benzenesulfonic acid |

| Sulfonate ester | Sulfo | RSO3R' | (-sulfonyl)oxy- or alkoxysulfonyl- |

R' R-sulfonate | Methyl trifluoromethanesulfonate or Methoxysulfonyl trifluoromethane (prefix) | |

| Thiocyanate | Thiocyanate | RSCN | thiocyanato- (-SCN) |

substituent thiocyanate |  Phenyl thiocyanate | |

| Isothiocyanate | RNCS | isothiocyanato- (-NCS) |

substituent isothiocyanate | Allyl isothiocyanate | ||

| Thioketone | Carbonothioyl | RCSR' |

|

-thioyl- (-CSR') or sulfanylidene- (=S) |

-thione | Diphenylmethanethione (Thiobenzophenone) |

| Thial | Carbonothioyl | RCSH |

|

methanethioyl- (-CSH) or sulfanylidene- (=S) |

-thial | |

| Thiocarboxylic acid | Carbothioic S-acid | RC=OSH |  |

mercaptocarbonyl- | -thioic S-acid |  Thiobenzoic acid (benzothioic S-acid) |

| Carbothioic O-acid | RC=SOH |  |

hydroxy(thiocarbonyl)- | -thioic O-acid | ||

| Thioester | Thiolester | RC=OSR' | S-alkyl-alkane-thioate | S-Methyl thioacrylate (S-Methyl prop-2-enethioate) | ||

| Thionoester | RC=SOR' | O-alkyl-alkane-thioate | ||||

| Dithiocarboxylic acid | Carbodithioic acid | RCS2H | dithiocarboxy- | -dithioic acid |  Dithiobenzoic acid (Benzenecarbodithioic acid) | |

| Dithiocarboxylic acid ester | Carbodithio | RC=SSR' | -dithioate |

Groups containing phosphorus

[edit]Compounds that contain phosphorus exhibit unique chemistry due to the ability of phosphorus to form more bonds than nitrogen, its lighter analogue on the periodic table.

| Chemical class | Group | Formula | Structural formula | Prefix | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphine (Phosphane) |

Phosphino | R3P | phosphanyl- | -phosphane | Methylpropylphosphane | |

| Phosphonic acid | Phosphono |

|

phosphono- | substituent phosphonic acid | Benzylphosphonic acid | |

| Phosphate | Phosphate |

|

phosphonooxy- or O-phosphono- (phospho-) |

substituent phosphate | Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (suffix) | |

O-Phosphonocholine (prefix) (Phosphocholine) | ||||||

| Phosphodiester | Phosphate | HOPO(OR)2 | [(alkoxy)hydroxyphosphoryl]oxy- or O-[(alkoxy)hydroxyphosphoryl]- |

di(substituent) hydrogen phosphate or phosphoric acid di(substituent) ester |

DNA | |

| O‑[(2‑Guanidinoethoxy)hydroxyphosphoryl]‑l‑serine (prefix) (Lombricine) |

Groups containing boron

[edit]Compounds containing boron exhibit unique chemistry due to their having partially filled octets and therefore acting as Lewis acids.

| Chemical class | Group | Formula | Structural formula | Prefix | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

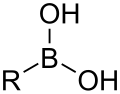

| Boronic acid | Borono | RB(OH)2 |  |

Borono- | substituent boronic acid |

|

| Boronic ester | Boronate | RB(OR)2 |  |

O-[bis(alkoxy)alkylboronyl]- | substituent boronic acid di(substituent) ester |

|

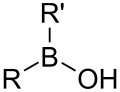

| Borinic acid | Borino | R2BOH |  |

Hydroxyborino- | di(substituent) borinic acid |

|

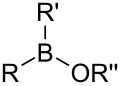

| Borinic ester | Borinate | R2BOR |  |

O-[alkoxydialkylboronyl]- | di(substituent) borinic acid substituent ester |

Groups containing metals

[edit]| Chemical class | Structural formula | Prefix | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alkyllithium | RLi | (tri/di)alkyl- | -lithium | |

| Alkylmagnesium halide | RMgX (X=Cl, Br, I)[note 1] | -magnesium halide | ||

| Alkylaluminium | Al2R6 | -aluminium |

| |

| Silyl ether | R3SiOR | -silyl ether |

|

note 1 Fluorine is too electronegative to be bonded to magnesium; it becomes an ionic salt instead.

Names of radicals or moieties

[edit]These names are used to refer to the moieties themselves or to radical species, and also to form the names of halides and substituents in larger molecules.

When the parent hydrocarbon is unsaturated, the suffix ("-yl", "-ylidene", or "-ylidyne") replaces "-ane" (e.g. "ethane" becomes "ethyl"); otherwise, the suffix replaces only the final "-e" (e.g. "ethyne" becomes "ethynyl").[4]

When used to refer to moieties, multiple single bonds differ from a single multiple bond. For example, a methylene bridge (methanediyl) has two single bonds, whereas a methylidene group (methylidene) has one double bond. Suffixes can be combined, as in methylidyne (triple bond) vs. methylylidene (single bond and double bond) vs. methanetriyl (three double bonds).

There are some retained names, such as methylene for methanediyl, 1,x-phenylene for phenyl-1,x-diyl (where x is 2, 3, or 4),[5] carbyne for methylidyne, and trityl for triphenylmethyl.

| Chemical class | Group | Formula | Structural formula | Prefix | Suffix | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single bond | R• | Ylo-[6] | -yl | |||

| Double bond | R: | ? | -ylidene | |||

| Triple bond | R⫶ | ? | -ylidyne | |||

| Carboxylic acyl radical | Acyl | R−C(=O)• | ? | -oyl |

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Compendium of Chemical Terminology (IUPAC "Gold Book") functional group Archived 2019-05-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ March, Jerry (1985). Advanced Organic Chemistry: Reactions, Mechanisms, and Structure (3rd ed.). New York: Wiley. ISBN 9780471854722. OCLC 642506595.

- ^ Brown, Theodore (2002). Chemistry: the central science. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 1001. ISBN 0130669970.

- ^ Moss, G. P.; W.H. Powell. "RC-81.1.1. Monovalent radical centers in saturated acyclic and monocyclic hydrocarbons, and the mononuclear EH4 parent hydrides of the carbon family". IUPAC Recommendations 1993. Department of Chemistry, Queen Mary University of London. Archived from the original on 9 February 2015. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ^ "R-2. 5 Substituent Prefix Names Derived from Parent Hydrides". IUPAC. 1993. Archived from the original on 2019-03-22. Retrieved 2018-12-15. section P-56.2.1

- ^ "Revised Nomenclature for Radicals, Ions, Radical Ions and Related Species (IUPAC Recommendations 1993: RC-81.3. Multiple radical centers)". Archived from the original on 2017-06-11. Retrieved 2014-12-02.

External links

[edit]- IUPAC Blue Book (organic nomenclature)

- "IUPAC ligand abbreviations" (PDF). IUPAC. 2 April 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- Functional group video

Functional group

View on Grokipedia- Alkenes and alkynes, featuring carbon-carbon double (C=C) and triple (C≡C) bonds, respectively, which confer unsaturation and enable addition reactions.[6]

- Carboxylic acids (-COOH), which are acidic due to the carboxyl group and form salts with bases.

- Amines (-NH₂, -NHR, or -NR₂), nitrogen-containing groups that act as bases and nucleophiles in biological and synthetic contexts.

- Halides (-X, where X is F, Cl, Br, or I), which serve as leaving groups in substitution and elimination reactions.[6]

Fundamentals

Definition and Characteristics

In organic chemistry, a functional group is defined as an atom or a group of atoms responsible for the characteristic chemical reactions of the parent molecule, exhibiting similar properties whenever it occurs in different compounds. This structural feature determines the family's physical and chemical behaviors, often independent of the surrounding molecular framework. According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), organic compounds typically consist of a relatively unreactive carbon-based backbone combined with one or more functional groups that dictate the compound's reactivity and properties.[1][9] Functional groups impart specific physical properties, such as polarity and acidity, which influence solubility, boiling points, and intermolecular forces in molecules. For instance, polar functional groups enable hydrogen bonding or dipole-dipole interactions, enhancing water solubility compared to nonpolar hydrocarbons. Chemically, they serve as primary sites of reactivity, where reactions preferentially occur due to localized electron density or bond strain; the carbon-carbon double bond in alkenes (denoted as C=C), for example, provides pi electrons that facilitate electrophilic addition reactions, distinguishing it from the saturated single bonds in alkanes. These characteristics allow chemists to predict molecular behavior based on the presence of such groups, regardless of the overall molecular size.[10][2][5] Understanding functional groups builds on the foundational structure of organic molecules, which are primarily composed of carbon atoms forming chains or rings with single, double, or triple bonds to hydrogen or other elements. This carbon skeleton provides stability, while functional groups introduce variability in reactivity. Unlike general substituents—such as alkyl or halogen groups that merely modify the parent chain without defining its principal chemical class—functional groups are the reactive moieties that establish the compound's core identity and reaction profile in nomenclature and synthesis.[4][11]Historical Development

The concept of functional groups in chemistry emerged from early observations of reactivity in the late 18th century, particularly through Antoine Lavoisier's work on combustion. Lavoisier demonstrated that oxygen plays a central role in combustion processes, interpreting it as a combination reaction rather than the release of phlogiston, which highlighted how specific elements could impart characteristic reactivity to compounds. This shift laid foundational insights into reactive components within substances, influencing the later recognition of atom groups responsible for similar behaviors across organic molecules.[12] In the 19th century, the field advanced significantly with Friedrich Wöhler's 1828 synthesis of urea from inorganic precursors, which challenged vitalism and spurred systematic study of organic structures. Wöhler, collaborating with Justus von Liebig, contributed to the radical theory, positing that stable groups of atoms—such as the benzoyl radical—act as persistent units in reactions, akin to elements in inorganic chemistry. This idea was formalized by Jean-Baptiste-André Dumas in the 1830s, who expanded the theory to explain substitution reactions in organic compounds, viewing molecules as assemblies of interchangeable radicals that dictate reactivity patterns. Liebig's development of analytical techniques further enabled the identification and classification of these groups, solidifying their role in organic analysis.[13] The term "functional group" emerged in the late 19th century, with its use becoming standardized at the 1892 Geneva Nomenclature Congress, where rules were established to indicate principal functional groups via suffixes in compound names. Hermann Kolbe's contributions in the 1850s emphasized how specific atom assemblages could be manipulated predictably in structural formulas, advancing the type theory alongside contemporaries like Charles Gerhardt. By the late 19th century, Jacobus Henricus van 't Hoff and Joseph Achille Le Bel independently proposed the tetrahedral arrangement of carbon atoms in 1874, integrating stereochemistry into structural theory and underscoring how functional groups influence spatial arrangements and reactivity. The 20th century refined the functional group concept through experimental and theoretical advancements. Spectroscopic techniques, evolving from early UV-visible methods to infrared and NMR spectroscopy in the mid-century, provided direct evidence of group-specific vibrational and magnetic properties, confirming their consistent behaviors across compounds. Concurrently, the advent of quantum mechanics in the 1920s, particularly the valence bond and molecular orbital theories developed by Walter Heitler, Fritz London, and others, offered a mechanistic explanation for the electronic delocalization and reactivity inherent to functional groups, bridging empirical observations with atomic-level understanding.Importance and Applications

Role in Organic Chemistry

Functional groups play a pivotal role in organic chemistry by serving as the primary sites of reactivity within molecules, enabling chemists to predict and generalize chemical behavior across diverse compounds. These groups, consisting of specific atoms or arrangements of atoms, dictate characteristic reactions regardless of the surrounding molecular structure. For example, carbonyl groups (C=O) consistently undergo nucleophilic addition or oxidation reactions, allowing predictions about how aldehydes or ketones will respond to reagents like reducing agents or nucleophiles. This predictive power stems from the localized electronic properties of functional groups, which influence bond strengths and electron densities, facilitating the classification of compounds into homologous series where reactivity patterns are consistent.[14] The structural organization provided by functional groups forms the foundation for systematic study in organic chemistry, as molecules are categorized based on their principal functional group. This approach groups compounds like alcohols (R-OH), which exhibit hydrogen bonding and acidity, separately from ketones (R-C(=O)-R), which are prone to enolization and carbonyl-specific reactions. Such classification simplifies the analysis of reaction mechanisms and synthetic planning, as compounds within the same family share analogous reactivity profiles, allowing chemists to apply established reaction conditions broadly. This organizational principle underpins the development of reaction databases and predictive models in computational organic chemistry.[15] In synthetic routes, functional groups are essential targets for interconversions, where one group is transformed into another to construct desired molecular architectures. These transformations, often involving oxidation, reduction, or substitution, exploit the inherent reactivity of the groups to achieve selectivity. A representative example is the oxidation of a primary alcohol to an aldehyde, which introduces a reactive carbonyl for further elaboration. This step is crucial in multi-step syntheses, as it allows progression along oxidation ladders while preserving the carbon skeleton.[16] The oxidation of primary alcohols to aldehydes is typically performed using pyridinium chlorochromate (PCC) in dichloromethane to avoid over-oxidation to carboxylic acids. The general transformation is represented as: Under these conditions, the reaction proceeds via chromate ester formation and subsequent elimination, yielding the aldehyde in high selectivity. This method exemplifies how functional group interconversions enable precise control in organic synthesis.[17]Applications in Synthesis and Biology

Functional groups serve as essential handles in organic synthesis, enabling chemists to direct reactivity and construct complex molecules through selective transformations. In multi-step syntheses, protecting groups are commonly employed to temporarily mask reactive functional groups, such as alcohols or amines, preventing unwanted side reactions while allowing modifications elsewhere in the molecule. For instance, the acetal protection of carbonyl groups facilitates the selective manipulation of other sites, a strategy pivotal in assembling intricate structures.[18][19] This approach proved crucial in the total synthesis of natural products like penicillin V, achieved by John C. Sheehan in 1957, where the β-lactam ring—a strained amide functional group—and the thiazolidine heterocycle were constructed via targeted activations of carboxylic acid and amine groups. The synthesis highlighted how functional groups dictate stereoselectivity and ring closure, yielding the antibiotic in a landmark demonstration of synthetic control over biologically active scaffolds.[20] In biological systems, functional groups underpin the structure and function of biomolecules, with phosphate groups forming the phosphodiester backbone of DNA for genetic stability and information transfer, while amide linkages in peptide bonds connect amino acids in proteins to enable folding and catalysis.[21] Enzyme specificity often relies on precise recognition of these groups; for example, proteases distinguish amide bonds in substrates through hydrogen bonding and steric fit at the active site, ensuring selective hydrolysis.[22] Contemporary applications extend to drug design, where sulfonamide groups mimic substrates to inhibit bacterial folate synthesis, as in sulfamethoxazole, revolutionizing antibiotic therapy since the 1930s.[23] Advances like click chemistry have further amplified these uses, particularly through copper-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC), a bioorthogonal reaction that ligates azide (R-N₃) and terminal alkyne (R'-C≡CH) groups to form stable 1,2,3-triazoles without interfering with living systems. This method, independently reported by Meldal and by Fokin/Sharpless in 2002, enables precise labeling of biomolecules in vivo. \ce{R-N3 + R'-C#CH ->[Cu(I) cat.] 1,4-disubstituted-1,2,3-triazole}Classification and Nomenclature

Classification by Composition

Functional groups in organic chemistry are classified primarily according to their elemental composition, which provides a framework for understanding their structural and reactive characteristics. The main categories encompass hydrocarbons, composed exclusively of carbon and hydrogen atoms; and heteroatom groups, which incorporate elements such as oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, halogens, and phosphorus. This system organizes functional groups based on the presence and type of heteroatoms or specific bond arrangements that confer distinct chemical behavior, with hydrocarbons acting as the foundational reference point lacking such elements.[24][25] The rationale for this compositional classification stems from the role of heteroatoms in altering molecular polarity and reactivity through differences in electronegativity, lone pair availability, and bond strengths compared to pure carbon-hydrogen frameworks. In hydrocarbons, baseline reactivity arises from sigma C-H bonds or pi bonds in unsaturated systems, whereas heteroatoms introduce sites for nucleophilic or electrophilic interactions; for example, the electronegative halogens in -X groups create polar C-X bonds susceptible to substitution, and oxygen in >C=O groups enables addition reactions due to the electrophilic carbonyl carbon. This approach highlights how elemental makeup dictates the group's influence on the overall molecule without overlapping into detailed reactivity profiles.[24][25] Subgroups within these categories are delineated by specific structural motifs, such as C=C for unsaturated hydrocarbons, -X for halogen-containing groups, and >C=O for carbonyls, each representing a non-exhaustive set of arrangements that define reactivity classes through their atomic connectivity. For instance, the double bond in alkenes introduces unsaturation to the hydrocarbon backbone, while the single bond to a halogen provides a leaving group potential, and the carbonyl's C=O linkage establishes a key electrophilic center. The following table provides a high-level overview of primary categories by elemental composition, including representative subgroups and general formulas:| Category | Key Element(s) | Representative Subgroups | General Formula |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrocarbons | C, H | Alkanes, Alkenes, Alkynes | R-H, RC=CR, RC≡CR |

| Halogen-Containing | F, Cl, Br, I | Alkyl halides | R-X |

| Oxygen-Containing | O | Alcohols, Ethers, Carbonyls | R-OH, R-OR', RC=O |

| Nitrogen-Containing | N | Amines, Nitriles | R-NH, R-C≡N |

| Sulfur-Containing | S | Thiols, Thioethers | R-SH, R-S-R |

Nomenclature Principles

In organic nomenclature, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) defines a strict seniority order for functional groups to ensure unambiguous naming of compounds. This order determines which functional group serves as the principal characteristic group, forming the basis of the parent hydride name and expressed as a suffix, while subordinate groups are cited as prefixes. The seniority is based on criteria such as oxidation state and structural complexity, as outlined in the IUPAC recommendations.[26] The highest-ranking classes include acids and their derivatives, which dictate the parent chain selection. For example, carboxylic acids receive the suffix -oic acid, and the carbon of the -COOH group is included in the chain numbering. Lower-ranking groups like alcohols use the suffix -ol only if no higher group is present. When multiple functional groups occur, the chain is chosen to contain the senior group, numbered from the end nearest to it, and subordinate groups receive prefixes such as hydroxy- for -OH or oxo- for =O in ketones when not principal. Multiplicative prefixes (e.g., di-, tri-) are employed for identical groups, with locants assigned to yield the lowest possible numbers.[27] The following table summarizes the seniority order for selected principal functional classes, from highest to lowest priority, with corresponding suffixes (for acyclic compounds) and example prefixes for subordinate use. This order is derived directly from IUPAC's Table 4.1 in the Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry (Blue Book, 2013).[27]| Seniority Rank | Class | Suffix (Principal) | Prefix (Subordinate) | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carboxylic acids | -oic acid | carboxy- | CH₃COOH: ethanoic acid |

| 2 | Carboxylic esters | -oate | alkoxycarbonyl- | CH₃COOCH₃: methyl ethanoate |

| 3 | Acid halides | -oyl halide | halocarbonyl- | CH₃COCl: ethanoyl chloride |

| 4 | Amides | -amide | carbamoyl- | CH₃CONH₂: ethanamide |

| 5 | Nitriles | -nitrile | cyano- | CH₃CN: ethanenitrile |

| 6 | Aldehydes | -al | formyl- | CH₃CHO: ethanal |

| 7 | Ketones | -one | oxo- | CH₃COCH₃: propan-2-one |

| 8 | Alcohols | -ol | hydroxy- | CH₃CH₂OH: ethanol |

| 9 | Amines | -amine | amino- | CH₃CH₂NH₂: ethanamine |

| 10 | Alkenes | -ene | - | CH₂=CH₂: ethene |

| 11 | Alkynes | -yne | - | HC≡CH: ethyne |

| 12 | Alkanes | -ane | - | CH₃CH₃: ethane |

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}\mathrm {C} }{-}{\overset {+}{\mathrm {N} }}{{\equiv }\mathrm {C} {\vphantom {A}}^{-}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/318b166027c3f5d010e17a4d7a67e3507f9841ef)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {RP} ({=}\mathrm {O} )(\mathrm {OH} ){\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7230c377b4b1d3072590da6c411ff3b1ad6e8e12)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {ROP} ({=}\mathrm {O} )(\mathrm {OH} ){\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c7f9fc53414b91c85b244fcd4a1f3cf95ab2c23c)