Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Taste

View on Wikipedia

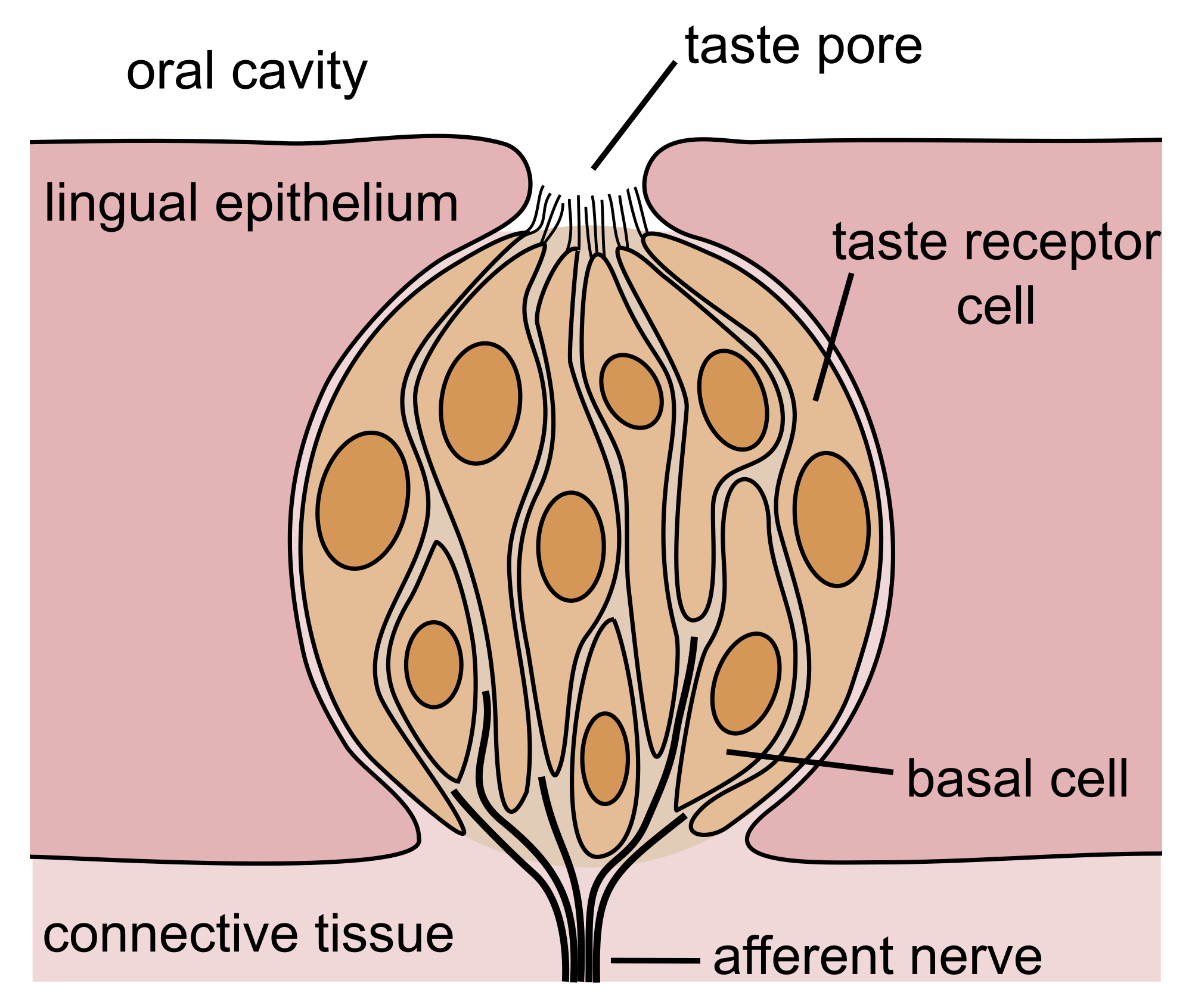

The gustatory system or sense of taste is the sensory system that is partially responsible for the perception of taste.[1] Taste is the perception stimulated when a substance in the mouth reacts chemically with taste receptor cells located on taste buds in the oral cavity, mostly on the tongue. Taste, along with the sense of smell and trigeminal nerve stimulation (registering texture, pain, and temperature), determines flavors of food and other substances. Humans have taste receptors on taste buds and other areas, including the upper surface of the tongue and the epiglottis.[2][3] The gustatory cortex is responsible for the perception of taste.

The tongue is covered with thousands of small bumps called papillae, which are visible to the naked eye.[2] Within each papilla are hundreds of taste buds.[1][4] The exceptions to this is the filiform papillae that do not contain taste buds. There are between 2000 and 5000[5] taste buds that are located on the back and front of the tongue. Others are located on the roof, sides and back of the mouth, and in the throat. Each taste bud contains 50 to 100 taste receptor cells.[6]

Taste receptors in the mouth sense the five basic tastes: sweetness, sourness, saltiness, bitterness, and savoriness (also known as savory or umami).[1][2][7][8] Scientific experiments have demonstrated that these five tastes exist and are distinct from one another. Taste buds are able to tell different tastes apart when they interact with different molecules or ions. Sweetness, savoriness, and bitter tastes are triggered by the binding of molecules to G protein-coupled receptors on the cell membranes of taste buds. Saltiness and sourness are perceived when alkali metals or hydrogen ions meet taste buds, respectively.[9][10]

The basic tastes contribute only partially to the sensation and flavor of food in the mouth—other factors include smell,[1] detected by the olfactory epithelium of the nose;[11] texture,[12] detected through a variety of mechanoreceptors, muscle nerves, etc.;[13] temperature, detected by temperature receptors; and "coolness" (such as of menthol) and "hotness" (pungency), by chemesthesis.

As the gustatory system senses both harmful and beneficial things, all basic tastes bring either caution or craving depending upon the effect the things they sense have on the body.[14] Sweetness helps to identify energy-rich foods, while bitterness warns people of poisons.[15]

Among humans, taste perception begins to fade during ageing, tongue papillae are lost, and saliva production slowly decreases.[16] Humans can also have distortion of tastes (dysgeusia). Not all mammals share the same tastes: some rodents can taste starch (which humans cannot), cats cannot taste sweetness, and several other carnivores, including hyenas, dolphins, and sea lions, have lost the ability to sense up to four of their ancestral five basic tastes.[17]

Basic tastes

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2016) |

The gustatory system allows animals to distinguish between safe and harmful food and to gauge different foods' nutritional value. Digestive enzymes in saliva begin to dissolve food into base chemicals that are washed over the papillae and detected as tastes by the taste buds. The tongue is covered with thousands of small bumps called papillae, which are visible to the naked eye. Within each papilla are hundreds of taste buds.[4] The exception to this are the filiform papillae, which do not contain taste buds. There are between 2,000 and 5,000[5] taste buds that are located on the back and front of the tongue. Others are located on the roof, sides and back of the mouth, and in the throat. Each taste bud contains 50 to 100 taste-receptor cells.[6]

The five specific tastes received by taste receptors are saltiness, sweetness, bitterness, sourness, and savoriness (often known by its Japanese name umami, which translates to 'deliciousness').

As of the early 20th century, Western physiologists and psychologists believed that there were four basic tastes: sweetness, sourness, saltiness, and bitterness. The concept of a "savory" taste was not present in Western science at that time, but was postulated in Japanese research.[18]

One study found that salt and sour taste mechanisms both detect, in different ways, the presence of sodium chloride (salt) in the mouth. Acids are also detected and perceived as sour.[19] The detection of salt is important to many organisms, but especially mammals, as it serves a critical role in ion and water homeostasis in the body. It is specifically needed in the mammalian kidney as an osmotically active compound that facilitates passive re-uptake of water into the blood.[20] Because of this, salt elicits a pleasant taste in most humans.

Sour and salt tastes can be pleasant in small quantities, but in larger quantities become more and more unpleasant to taste. For sour taste, this presumably is because the sour taste can signal under-ripe fruit, rotten meat, and other spoiled foods, which can be dangerous to the body because of bacteria that grow in such media. Additionally, sour taste signals acids, which can cause serious tissue damage.

Sweet taste signals the presence of carbohydrates in solution.[21] Since carbohydrates have a very high calorie count (saccharides have many bonds, therefore much energy),[22] they are essential to the human body, which evolved to seek out the highest-calorie-intake foods.[23] They are used as direct energy (sugars) and storage of energy (glycogen). Many non-carbohydrate molecules trigger a sweet response, leading to the development of many artificial sweeteners, including saccharin, sucralose, and aspartame. It is still unclear how these substances activate the sweet receptors and what adaptative significance this has had.

The savory taste (known in Japanese as umami), identified by Japanese chemist Kikunae Ikeda, signals the presence of the amino acid L-glutamate. The amino acids in proteins are used in the body to build muscles and organs, and to transport molecules (hemoglobin), antibodies, and the organic catalysts known as enzymes. These are all critical molecules, and it is important to have a steady supply of amino acids; consequently, savory tastes trigger a pleasurable response, encouraging the intake of peptides and proteins.

Pungency (piquancy or hotness) had traditionally been considered a sixth basic taste.[24] In 2015, researchers suggested a new basic taste of fatty acids called "fat taste",[25] although "oleogustus" and "pinguis" have both been proposed as alternate terms.[26][27]

Sweetness

[edit]

Sweetness, usually regarded as a pleasurable sensation, is produced by the presence of sugars and substances that mimic sugar. Sweetness may be connected to aldehydes and ketones, which contain a carbonyl group. Sweetness is detected by a variety of G protein coupled receptors (GPCR) coupled to the G protein gustducin found on the taste buds. At least two different variants of the "sweetness receptors" must be activated for the brain to register sweetness. Compounds the brain senses as sweet are compounds that can bind with varying bond strength to two different sweetness receptors. These receptors are T1R2+3 (heterodimer) and T1R3 (homodimer), which account for all sweet sensing in humans and animals.[28][29]

Taste detection thresholds for sweet substances are rated relative to sucrose, which has an index of 1.[30][31] The average human detection threshold for sucrose is 10 millimoles per liter. For lactose it is 30 millimoles per liter, with a sweetness index of 0.3,[30] and 5-nitro-2-propoxyaniline 0.002 millimoles per liter. "Natural" sweeteners such as saccharides activate the GPCR, which releases gustducin. The gustducin then activates the molecule adenylate cyclase, which catalyzes the production of the molecule cAMP, or adenosine 3', 5'-cyclic monophosphate. This molecule closes potassium ion channels, leading to depolarization and neurotransmitter release. Synthetic sweeteners such as saccharin activate different GPCRs and induce taste receptor cell depolarization by an alternate pathway.

Sourness

[edit]

Sourness is the taste that describes acidity. The sourness of substances is rated relative to dilute hydrochloric acid, which has a sourness index of 1. By comparison, tartaric acid has a sourness index of 0.7, citric acid an index of 0.46, and carbonic acid an index of 0.06.[30][31]

Sour taste is detected by a small subset of cells that are distributed across all taste buds called Type III taste receptor cells. H+ ions (protons) that are abundant in sour substances can directly enter the Type III taste cells through a proton channel.[32] This channel was identified in 2018 as otopetrin 1 (OTOP1).[33] The transfer of positive charge into the cell can itself trigger an electrical response. Some weak acids such as acetic acid can also penetrate taste cells; intracellular hydrogen ions inhibit potassium channels, which normally function to hyperpolarize the cell. By a combination of direct intake of hydrogen ions through OTOP1 ion channels (which itself depolarizes the cell) and the inhibition of the hyperpolarizing channel, sourness causes the taste cell to fire action potentials and release neurotransmitter.[34]

The most common foods with natural sourness are fruits, such as lemon, lime, grape, orange, tamarind, and bitter melon. Fermented foods, such as wine, vinegar or yogurt, may have sour taste. Children show a greater enjoyment of sour flavors than adults,[35] and sour candy containing citric acid or malic acid is common.

Saltiness

[edit]Saltiness taste seems to have two components: a low-salt signal and a high-salt signal. The low-salt signal causes a sensation of deliciousness, while the high-salt signal typically causes the sensation of "too salty".[36]

The low-salt signal is understood to be caused by the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC), which is composed of three subunits. ENaC in the taste cells allow sodium cations to enter the cell. This on its own depolarizes the cell, and opens voltage-dependent calcium channels, flooding the cell with positive calcium ions and leading to neurotransmitter release. ENaC can be blocked by the drug amiloride in many mammals, especially rats. The sensitivity of the low-salt taste to amiloride in humans is much less pronounced, leading to conjecture that there may be additional low-salt receptors besides ENaC to be discovered.[36]

A number of similar cations also trigger the low salt signal. The size of lithium and potassium ions most closely resemble those of sodium, and thus the saltiness is most similar. In contrast, rubidium and caesium ions are far larger, so their salty taste differs accordingly.[citation needed] The saltiness of substances is rated relative to sodium chloride (NaCl), which has an index of 1.[30][31] Potassium, as potassium chloride (KCl), is the principal ingredient in salt substitutes and has a saltiness index of 0.6.[30][31]

Other monovalent cations, e.g. ammonium (NH4+), and divalent cations of the alkali earth metal group of the periodic table, e.g. calcium (Ca2+), ions generally elicit a bitter rather than a salty taste even though they, too, can pass directly through ion channels in the tongue, generating an action potential. But the chloride of calcium is saltier and less bitter than potassium chloride, and is commonly used in pickle brine instead of KCl.[citation needed]

The high-salt signal is poorly understood. This signal is not blocked by amiloride in rodents. Sour and bitter cells trigger on high chloride levels, but the specific receptor is unidentified.[36]

Bitterness

[edit]

Bitterness is one of the most sensitive of the tastes, and many perceive it as unpleasant, sharp, or disagreeable, but it is sometimes desirable and intentionally added via various bittering agents. Common bitter foods and beverages include coffee, unsweetened cocoa, South American mate, coca tea, bitter gourd, uncured olives, citrus peel, some varieties of cheese, many plants in the family Brassicaceae, dandelion greens, horehound, wild chicory, and escarole. The ethanol in alcoholic beverages tastes bitter,[37] as do the additional bitter ingredients found in some alcoholic beverages including hops in beer and gentian in bitters. Quinine is also known for its bitter taste and is found in tonic water.

Bitterness is of interest to those who study evolution, as well as various health researchers[30][38] since a large number of natural bitter compounds are known to be toxic. The ability to detect bitter-tasting, toxic compounds at low thresholds is considered to provide an important protective function.[30][38][39] Plant leaves often contain toxic compounds, and among leaf-eating primates there is a tendency to prefer immature leaves, which tend to be higher in protein and lower in fiber and poisons than mature leaves.[40] Amongst humans, various food processing techniques are used worldwide to detoxify otherwise inedible foods and make them palatable.[41] Furthermore, the use of fire, changes in diet, and avoidance of toxins has led to neutral evolution in human bitter sensitivity. This has allowed several loss of function mutations that has led to a reduced sensory capacity towards bitterness in humans when compared to other species.[42]

The threshold for stimulation of bitter taste by quinine averages a concentration of 8 μM (8 micromolar).[30] The taste thresholds of other bitter substances are rated relative to quinine, which is thus given a reference index of 1.[30][31] For example, brucine has an index of 11, is thus perceived as intensely more bitter than quinine, and is detected at a much lower solution threshold.[30] The most bitter natural substance is amarogentin, a compound present in the roots of the plant Gentiana lutea, and the most bitter substance known is the synthetic chemical denatonium,[contradictory] which has an index of 1,000.[31] It is used as an aversive agent (a bitterant) that is added to toxic substances to prevent accidental ingestion. It was discovered accidentally in 1958 during research on a local anesthetic by T. & H. Smith of Edinburgh, Scotland.[43][44]

Research has shown that TAS2Rs (taste receptors, type 2, also known as T2Rs) such as TAS2R38 coupled to the G protein gustducin are responsible for the human ability to taste bitter substances.[45] They are identified not only by their ability to taste for certain "bitter" ligands, but also by the morphology of the receptor itself (surface bound, monomeric).[19] The TAS2R family in humans is thought to comprise about 25 different taste receptors, some of which can recognize a wide variety of bitter-tasting compounds.[46] Over 670 bitter-tasting compounds have been identified, on a bitter database, of which over 200 have been assigned to one or more specific receptors.[47] It is speculated that the selective constraints on the TAS2R family have been weakened due to the relatively high rate of mutation and pseudogenization.[48] Researchers use two synthetic substances, phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) and 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) to study the genetics of bitter perception. These two substances taste bitter to some people, but are virtually tasteless to others. Among the tasters, some are so-called "supertasters" to whom PTC and PROP are extremely bitter. The variation in sensitivity is determined by two common alleles at the TAS2R38 locus.[49] This genetic variation in the ability to taste a substance has been a source of great interest to those who study genetics.

Gustducin is made of three subunits. When it is activated by the GPCR, its subunits break apart and activate phosphodiesterase, a nearby enzyme, which in turn converts a precursor within the cell into a secondary messenger, which closes potassium ion channels.[citation needed] Also, this secondary messenger can stimulate the endoplasmic reticulum to release Ca2+ which contributes to depolarization. This leads to a build-up of potassium ions in the cell, depolarization, and neurotransmitter release. It is also possible for some bitter tastants to interact directly with the G protein, because of a structural similarity to the relevant GPCR.

The most bitter substance known as of 2025[update] – oligoporin D – stimulates the bitter taste receptor type TAS2R46 at the lowest concentrations 100 nM (0.1 micromolar, approx. 63 millionths of a gram/liter).[50][51]

Savoriness

[edit]Savoriness, or umami, is an appetitive taste.[14][18] It can be tasted in soy sauce, meat, dashi and consomme. Umami, a loanword from Japanese meaning "good flavor" or "good taste",[52] which is similar to the word "savory" that comes from the French for "tasty". Umami (旨味) is considered fundamental to many East Asian cuisines,[53] such as Japanese cuisine.[54] It dates back to the use of fermented fish sauce: garum in ancient Rome[55] and ge-thcup or koe-cheup in ancient China.[56]

Umami was first studied in 1907 by Ikeda isolating dashi taste, which he identified as the chemical monosodium glutamate (MSG).[18][57] MSG is a sodium salt that produces a strong savory taste, especially combined with foods rich in nucleotides such as meats, fish, nuts, and mushrooms.[58]

Some savory taste buds respond specifically to glutamate in the same way that "sweet" ones respond to sugar. Glutamate binds to a variant of G protein coupled glutamate receptors.[59][60] L-glutamate may bond to a type of GPCR known as a metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR4) which causes the G-protein complex to activate the sensation of umami.[60]

Perceptual independence from salty and sweet taste

[edit]There are doubts regarding whether umami is different from salty taste, as standalone glutamate (glutamic acid) without table salt ions (Na+), is perceived as sour, salt taste blockers reduce discrimination between monosodium glutamate and sucrose in rodents, since sweet and umami tastes share a taste receptor subunit; and part of the human population cannot tell apart umami from salty.[61]

If umami does not have perceptual independence, it could be classified with other tastes like fat, carbohydrate, metallic, and calcium, which can be perceived at high concentrations but may not offer a prominent taste experience.[61]

Measuring relative tastes

[edit]Measuring the degree to which a substance presents one basic taste can be achieved in a subjective way by comparing its taste to a reference substance.

Sweetness is subjectively measured by comparing the threshold values, or level at which the presence of a dilute substance can be detected by a human taster, of different sweet substances.[62] Substances are usually measured relative to sucrose,[63] which is usually given an arbitrary index of 1[64][65] or 100.[66] Rebaudioside A is 100 times sweeter than sucrose; fructose is about 1.4 times sweeter; glucose, a sugar found in honey and vegetables, is about three-quarters as sweet; and lactose, a milk sugar, is one-half as sweet.[b][62]

The sourness of a substance can be rated by comparing it to very dilute hydrochloric acid (HCl).[67]

Relative saltiness can be rated by comparison to a dilute salt solution.[68]

Quinine, a bitter medicinal found in tonic water, can be used to subjectively rate the bitterness of a substance.[69] Units of dilute quinine hydrochloride (1 g in 2000 mL of water) can be used to measure the threshold bitterness concentration, the level at which the presence of a dilute bitter substance can be detected by a human taster, of other compounds.[69] More formal chemical analysis, while possible, is difficult.[69]

There may not be an absolute measure for pungency, though there are tests for measuring the subjective presence of a given pungent substance in food, such as the Scoville scale for capsaicine in peppers or the Pyruvate scale for pyruvates in garlics and onions.

Functional structure

[edit]

Taste is a form of chemoreception which occurs in the specialised taste receptors in the mouth. To date, there are five different types of taste these receptors can detect which are recognized: salt, sweet, sour, bitter, and umami. Each type of receptor has a different manner of sensory transduction: that is, of detecting the presence of a certain compound and starting an action potential which alerts the brain. It is a matter of debate whether each taste cell is tuned to one specific tastant or to several; Smith and Margolskee claim that "gustatory neurons typically respond to more than one kind of stimulus, [a]lthough each neuron responds most strongly to one tastant". Researchers believe that the brain interprets complex tastes by examining patterns from a large set of neuron responses. This enables the body to make "keep or spit out" decisions when there is more than one tastant present. "No single neuron type alone is capable of discriminating among stimuli or different qualities, because a given cell can respond the same way to disparate stimuli."[70] As well, serotonin is thought to act as an intermediary hormone which communicates with taste cells within a taste bud, mediating the signals being sent to the brain. Receptor molecules are found on the top of microvilli of the taste cells.

Sweetness

[edit]Sweetness is produced by the presence of sugars, some proteins, and other substances such as alcohols like anethol, glycerol and propylene glycol, saponins such as glycyrrhizin, artificial sweeteners (organic compounds with a variety of structures), and lead compounds such as lead acetate.[citation needed] It is often connected to aldehydes and ketones, which contain a carbonyl group.[citation needed] Many foods can be perceived as sweet regardless of their actual sugar content. For example, some plants such as liquorice, anise or stevia can be used as sweeteners. Rebaudioside A is a steviol glycoside coming from stevia that is 200 times sweeter than sugar. Lead acetate and other lead compounds were used as sweeteners, mostly for wine, until lead poisoning became known. Romans used to deliberately boil the must inside of lead vessels to make a sweeter wine. Sweetness is detected by a variety of G protein-coupled receptors coupled to a G protein that acts as an intermediary in the communication between taste bud and brain, gustducin.[71] These receptors are T1R2+3 (heterodimer) and T1R3 (homodimer), which account for sweet sensing in humans and other animals.[72]

Saltiness

[edit]Saltiness is a taste produced best by the presence of cations (such as Na+

, K+

or Li+

)[73] and is directly detected by cation influx into glial like cells via leak channels causing depolarisation of the cell.[73]

Sourness

[edit]Sourness is acidity,[74][75] and, like salt, it is a taste sensed using ion channels.[73] Undissociated acid diffuses across the plasma membrane of a presynaptic cell, where it dissociates in accordance with Le Chatelier's principle. The protons that are released then block potassium channels, which depolarise the cell and cause calcium influx. In addition, the taste receptor PKD2L1 has been found to be involved in tasting sour.[76]

Bitterness

[edit]Research has shown that TAS2Rs (taste receptors, type 2, also known as T2Rs) such as TAS2R38 are responsible for the ability to taste bitter substances in vertebrates.[77] They are identified not only by their ability to taste certain bitter ligands, but also by the morphology of the receptor itself (surface bound, monomeric).[78]

Savoriness

[edit]The amino acid glutamic acid is responsible for savoriness,[79][80] but some nucleotides (inosinic acid[54][81] and guanylic acid[79]) can act as complements, enhancing the taste.[54][81]

Glutamic acid binds to a variant of the G protein-coupled receptor, producing a savory taste.[59][60]

Further sensations and transmission

[edit]The tongue can also feel other sensations not generally included in the basic tastes. These are largely detected by the somatosensory system. In humans, the sense of taste is conveyed via three of the twelve cranial nerves. The facial nerve (VII) carries taste sensations from the anterior two thirds of the tongue, the glossopharyngeal nerve (IX) carries taste sensations from the posterior one third of the tongue while a branch of the vagus nerve (X) carries some taste sensations from the back of the oral cavity.

The trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V) provides information concerning the general texture of food as well as the taste-related sensations of peppery or hot (from spices).

Pungency (also spiciness or hotness)

[edit]Substances such as ethanol and capsaicin cause a burning sensation by inducing a trigeminal nerve reaction together with normal taste reception. The sensation of heat is caused by the food's activating nerves that express TRPV1 and TRPA1 receptors. Some such plant-derived compounds that provide this sensation are capsaicin from chili peppers, piperine from black pepper, gingerol from ginger root and allyl isothiocyanate from horseradish. The piquant ("hot" or "spicy") sensation provided by such foods and spices plays an important role in a diverse range of cuisines across the world—especially in equatorial and sub-tropical climates, such as Ethiopian, Peruvian, Hungarian, Indian, Korean, Indonesian, Lao, Malaysian, Mexican, New Mexican, Pakistani, Singaporean, Southwest Chinese (including Sichuan cuisine), Vietnamese, and Thai cuisines.

This particular sensation, called chemesthesis, is not a taste in the technical sense, because the sensation does not arise from taste buds, and a different set of nerve fibers carry it to the brain. Foods like chili peppers activate nerve fibers directly; the sensation interpreted as "hot" results from the stimulation of somatosensory (pain/temperature) fibers on the tongue. Many parts of the body with exposed membranes but no taste sensors (such as the nasal cavity, under the fingernails, surface of the eye or a wound) produce a similar sensation of heat when exposed to hotness agents.

Coolness

[edit]Some substances activate cold trigeminal receptors even when not at low temperatures. This "fresh" or "minty" sensation can be tasted in peppermint and spearmint and is triggered by substances such as menthol, anethol, ethanol, and camphor. Caused by activation of the same mechanism that signals cold, TRPM8 ion channels on nerve cells, unlike the actual change in temperature described for sugar substitutes, this coolness is only a perceived phenomenon.

Numbness

[edit]Both Chinese and Batak Toba cooking include the idea of 麻 (má) or mati rasa, a tingling numbness caused by spices such as Sichuan pepper. The cuisines of Sichuan province in China and of the Indonesian province of North Sumatra often combine this with chili pepper to produce a 麻辣 málà, "numbing-and-hot", or "mati rasa" flavor.[82] Typical in northern Brazilian cuisine, jambu is an herb used in dishes like tacacá. These sensations, although not taste, fall into a category of chemesthesis.

Astringency

[edit]Some foods, such as unripe fruits, contain tannins or calcium oxalate that cause an astringent or puckering sensation of the mucous membrane of the mouth. Examples include tea, red wine, or rhubarb.[citation needed] Other terms for the astringent sensation are "dry", "rough", "harsh" (especially for wine), "tart" (normally referring to sourness), "rubbery", "hard" or "styptic".[83]

Metallicness

[edit]A metallic taste may be caused by food and drink, certain medicines or amalgam dental fillings. It is generally considered an off flavor when present in food and drink. A metallic taste may be caused by galvanic reactions in the mouth. In the case where it is caused by dental work, the dissimilar metals used may produce a measurable current.[84] Some artificial sweeteners are perceived to have a metallic taste, which is detected by the TRPV1 receptors.[85] Many people consider blood to have a metallic taste.[86][87] A metallic taste in the mouth is also a symptom of various medical conditions, in which case it may be classified under the symptoms dysgeusia or parageusia, referring to distortions of the sense of taste,[88] and can be caused by medication, including saquinavir,[88] zonisamide,[89] and various kinds of chemotherapy,[90] as well as occupational hazards, such as working with pesticides.[91]

Fat taste

[edit]Recent research reveals a potential taste receptor called the CD36 receptor.[92][93][94] CD36 was targeted as a possible lipid taste receptor because it binds to fat molecules (more specifically, long-chain fatty acids),[95] and it has been localized to taste bud cells (specifically, the circumvallate and foliate papillae).[96] There is a debate over whether we can truly taste fats, and supporters of human ability to taste free fatty acids (FFAs) have based the argument on a few main points: there is an evolutionary advantage to oral fat detection; a potential fat receptor has been located on taste bud cells; fatty acids evoke specific responses that activate gustatory neurons, similar to other currently accepted tastes; and, there is a physiological response to the presence of oral fat.[97] Although CD36 has been studied primarily in mice, research examining human subjects' ability to taste fats found that those with high levels of CD36 expression were more sensitive to tasting fat than were those with low levels of CD36 expression;[98] this study points to a clear association between CD36 receptor quantity and the ability to taste fat.

Other possible fat taste receptors have been identified. G protein-coupled receptors free fatty acid receptor 4 (also termed GPR120) and to a much lesser extent Free fatty acid receptor 1 (also termed GPR40)[99] have been linked to fat taste, because their absence resulted in reduced preference to two types of fatty acid (linoleic acid and oleic acid), as well as decreased neuronal response to oral fatty acids.[100]

Monovalent cation channel TRPM5 has been implicated in fat taste as well,[101] but it is thought to be involved primarily in downstream processing of the taste rather than primary reception, as it is with other tastes such as bitter, sweet, and savory.[97]

Proposed alternate names to fat taste include oleogustus[102] and pinguis,[27] although these terms are not widely accepted. The main form of fat that is commonly ingested is triglycerides, which are composed of three fatty acids bound together. In this state, triglycerides are able to give fatty foods unique textures that are often described as creaminess. But this texture is not an actual taste. It is only during ingestion that the fatty acids that make up triglycerides are hydrolysed into fatty acids via lipases. The taste is commonly related to other, more negative, tastes such as bitter and sour due to how unpleasant the taste is for humans. Richard Mattes, a co-author of the study, explained that low concentrations of these fatty acids can create an overall better flavor in a food, much like how small uses of bitterness can make certain foods more rounded. A high concentration of fatty acids in certain foods is generally considered inedible.[103] To demonstrate that individuals can distinguish fat taste from other tastes, the researchers separated volunteers into groups and had them try samples that also contained the other basic tastes. Volunteers were able to separate the taste of fatty acids into their own category, with some overlap with savory samples, which the researchers hypothesized was due to poor familiarity with both. The researchers note that the usual "creaminess and viscosity we associate with fatty foods is largely due to triglycerides", unrelated to the taste; while the actual taste of fatty acids is not pleasant. Mattes described the taste as "more of a warning system" that a certain food should not be eaten.[104]

There are few regularly consumed foods rich in fat taste, due to the negative flavor that is evoked in large quantities. Foods whose flavor to which fat taste makes a small contribution include olive oil and fresh butter, along with various kinds of vegetable and nut oils.[105]

Heartiness

[edit]Kokumi (/koʊkuːmi/, Japanese: kokumi (コク味)[106] from koku (こく)[106]) is translated as "heartiness", "full flavor" or "rich" and describes compounds in food that do not have their own taste, but enhance the characteristics when combined.

Alongside the five basic tastes of sweet, sour, salt, bitter and savory, kokumi has been described as something that may enhance the other five tastes by magnifying and lengthening the other tastes, or "mouthfulness".[107]: 290 [108] Garlic is a common ingredient to add flavor used to help define the characteristic kokumi flavors.[108]

Calcium-sensing receptors (CaSR) are receptors for kokumi substances which, applied around taste pores, induce an increase in the intracellular Ca concentration in a subset of cells.[107] This subset of CaSR-expressing taste cells are independent from the influenced basic taste receptor cells.[109] CaSR agonists directly activate the CaSR on the surface of taste cells and integrated in the brain via the central nervous system. A basal level of calcium, corresponding to the physiological concentration, is necessary for activation of the CaSR to develop the kokumi sensation.[110]

Calcium

[edit]The distinctive taste of chalk has been identified as the calcium component of that substance.[111] In 2008, geneticists discovered a calcium receptor on the tongues of mice. The CaSR receptor is commonly found in the gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, and brain. Along with the "sweet" T1R3 receptor, the CaSR receptor can detect calcium as a taste. Whether the perception exists or not in humans is unknown.[112][113]

Temperature

[edit]Temperature can be an essential element of the taste experience. Heat can accentuate some flavors and decrease others by varying the density and phase equilibrium of a substance. Food and drink that—in a given culture—is traditionally served hot is often considered distasteful if cold, and vice versa. For example, alcoholic beverages, with a few exceptions, are usually thought best when served at room temperature or chilled to varying degrees, but soups—again, with exceptions—are usually only eaten hot. A cultural example are soft drinks. In North America it is almost always preferred cold, regardless of season.

Starchiness

[edit]A 2016 study suggested that humans can taste starch (specifically, a glucose oligomer) independently of other tastes such as sweetness, without suggesting an associated chemical receptor.[114][115][116]

Nerve supply and neural connections

[edit]

The glossopharyngeal nerve innervates a third of the tongue including the circumvallate papillae. The facial nerve innervates the other two thirds of the tongue and the cheek via the chorda tympani.[117]

The pterygopalatine ganglia are ganglia (one on each side) of the soft palate. The greater petrosal, lesser palatine and zygomatic nerves all synapse here. The greater petrosal carries soft palate taste signals to the facial nerve. The lesser palatine sends signals to the nasal cavity, which is why spicy foods cause nasal drip. The zygomatic sends signals to the lacrimal nerve that activate the lacrimal gland, which is the reason that spicy foods can cause tears. Both the lesser palatine and the zygomatic are maxillary nerves (from the trigeminal nerve).

The special visceral afferents of the vagus nerve carry taste from the epiglottal region of the tongue.

The lingual nerve (trigeminal, not shown in diagram) is deeply interconnected with the chorda tympani in that it provides all other sensory info from the anterior two-thirds of the tongue.[118] This info is processed separately (nearby) in the rostral lateral subdivision of the nucleus of the solitary tract (NST).

The NST receives input from the amygdala (regulates oculomotor nuclei output), bed nuclei of stria terminalis, hypothalamus, and prefrontal cortex. The NST is the topographical map that processes gustatory and sensory (temp, texture, etc.) info.[119]

The reticular formation (includes Raphe nuclei responsible for serotonin production) is signaled to release serotonin during and after a meal to suppress appetite.[120] Similarly, salivary nuclei are signaled to decrease saliva secretion.

Hypoglossal and thalamic connections aid in oral-related movements.

Hypothalamus connections hormonally regulate hunger and the digestive system.

Substantia innominata connects the thalamus, temporal lobe, and insula.

Edinger-Westphal nucleus reacts to taste stimuli by dilating and constricting the pupils.[121]

Spinal ganglia are involved in movement.

The frontal operculum is speculated to be the memory and association hub for taste.[citation needed]

The insula cortex aids in swallowing and gastric motility.[122][123]

Taste in insects

[edit]Insects taste using small hair-like structures called taste sensilla, specialized sensory organs located on various body parts such as the mouthparts, legs, and wings. These sensilla contain gustatory receptor neurons (GRNs) sensitive to a wide range of chemical stimuli.

Insects respond to sugar, bitter, acid, and salt tastes. However, their taste spectrum extends to include water, fatty acids, metals, carbonation, RNA, ATP, and pheromones. Detecting these substances is vital for behaviors like feeding, mating, and oviposition.

Invertebrates' ability to taste these compounds is fundamental to their survival and provides insights into the evolution of sensory systems. This knowledge is crucial for understanding insect behavior and has applications in pest control and pollination biology.

Other concepts

[edit]Supertasters

[edit]A supertaster is a person whose sense of taste is significantly more sensitive than most. The cause of this heightened response is likely, at least in part, due to an increased number of fungiform papillae.[124] Studies have shown that supertasters require less fat and sugar in their food to get the same satisfying effects. These people tend to consume more salt than others. This is due to their heightened sense of the taste of bitterness, and the presence of salt drowns out the taste of bitterness.[125]

Aftertaste

[edit]Aftertastes arise after food has been swallowed. An aftertaste can differ from the food it follows. Medicines and tablets may also have a lingering aftertaste, as they can contain certain artificial flavor compounds, such as aspartame (artificial sweetener).

Acquired taste

[edit]An acquired taste often refers to an appreciation for a food or beverage that is unlikely to be enjoyed by a person who has not had substantial exposure to it, usually because of some unfamiliar aspect of the food or beverage, including bitterness, a strong or strange odor, taste, or appearance.

Clinical significance

[edit]Patients with Addison's disease, pituitary insufficiency, or cystic fibrosis sometimes have a hyper-sensitivity to the five primary tastes.[126]

Disorders of taste

[edit]- ageusia (complete loss of taste)

- hypogeusia (reduced sense of taste)

- dysgeusia (distortion in sense of taste)

- hypergeusia (abnormally heightened sense of taste)

Viruses can also cause loss of taste. About 50% of patients with SARS-CoV-2 (causing COVID-19) experience some type of disorder associated with their sense of smell or taste, including ageusia and dysgeusia. SARS-CoV-1, MERS-CoV and even the flu (influenza virus) can also disrupt olfaction.[127][128]

History

[edit]In the West, Aristotle postulated in c. 350 BC[129] that the two most basic tastes were sweet and bitter.[130] He was one of the first persons to develop a list of basic tastes.[131]

Research

[edit]The receptors for the basic tastes of bitter, sweet and savory have been identified. They are G protein-coupled receptors.[132] The cells that detect sourness have been identified as a subpopulation that express the protein PKD2L1, and The responses are mediated by an influx of protons into the cells.[132] As of 2019, molecular mechanisms for each taste appear to be different, although all taste perception relies on activation of P2X purinoreceptors on sensory nerves.[133]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]On the basis of physiologic studies, there are generally believed to be at least four primary sensations of taste: sour, salty, sweet, and bitter. Yet we know that a person can perceive literally hundreds of different tastes. These are all supposed to be combinations of the four primary sensations...However, there might be other less conspicuous classes or subclasses of primary sensations",[134]

b. ^ Some variation in values is not uncommon between various studies. Such variations may arise from a range of methodological variables, from sampling to analysis and interpretation. In fact there is a "plethora of methods"[135] Indeed, the taste index of 1, assigned to reference substances such as sucrose (for sweetness), hydrochloric acid (for sourness), quinine (for bitterness), and sodium chloride (for saltiness), is itself arbitrary for practical purposes.[67]

Some values, such as those for maltose and glucose, vary little. Others, such as aspartame and sodium saccharin, have much larger variation. Regardless of variation, the perceived intensity of substances relative to each reference substance remains consistent for taste ranking purposes. The indices table for McLaughlin & Margolskee (1994) for example,[30][31] is essentially the same as that of Svrivastava & Rastogi (2003),[136] Guyton & Hall (2006),[67] and Joesten et al. (2007).[64] The rankings are all the same, with any differences, where they exist, being in the values assigned from the studies from which they derive.

As for the assignment of 1 or 100 to the index substances, this makes no difference to the rankings themselves, only to whether the values are displayed as whole numbers or decimal points. Glucose remains about three-quarters as sweet as sucrose whether displayed as 75 or 0.75.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Trivedi, Bijal P. (2012). "Gustatory system: The finer points of taste". Nature. 486 (7403): S2 – S3. Bibcode:2012Natur.486S...2T. doi:10.1038/486s2a. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 22717400. S2CID 4325945.

- ^ a b c Witt, Martin (2019). "Anatomy and development of the human taste system". Smell and Taste. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 164. pp. 147–171. doi:10.1016/b978-0-444-63855-7.00010-1. ISBN 978-0-444-63855-7. ISSN 0072-9752. PMID 31604544. S2CID 204332286.

- ^ Human biology (Page 201/464) Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine Daniel D. Chiras. Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2005.

- ^ a b Schacter, Daniel (2009). Psychology Second Edition. United States of America: Worth Publishers. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-4292-3719-2.

- ^ a b Boron, W.F., E.L. Boulpaep. 2003. Medical Physiology. 1st ed. Elsevier Science USA.

- ^ a b Roper, Stephen D.; Chaudhari, Nirupa (August 2017). "Taste buds: cells, signals and synapses". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 18 (8): 485–497. doi:10.1038/nrn.2017.68. ISSN 1471-0048. PMC 5958546. PMID 28655883.

- ^ Kean, Sam (Fall 2015). "The science of satisfaction". Distillations Magazine. 1 (3): 5. Archived from the original on 17 November 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ "How does our sense of taste work?". PubMed. 6 January 2012. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2016.

- ^ Human Physiology: An integrated approach 5th Edition -Silverthorn, Chapter-10, Page-354

- ^ Turner, Heather N.; Liman, Emily R. (10 February 2022). "The Cellular and Molecular Basis of Sour Taste". Annual Review of Physiology. 84 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-060121-041637. ISSN 0066-4278. PMC 10191257. PMID 34752707. S2CID 243940546.

- ^ Smell – The Nose Knows Archived 13 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine washington.edu, Eric H. Chudler.

- ^

- Food texture: measurement and perception (page 36/311) Andrew J. Rosenthal. Springer, 1999.

- Food texture: measurement and perception (page 3/311) Andrew J. Rosenthal. Springer, 1999.

- ^ Food texture: measurement and perception (page 4/311) Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine Andrew J. Rosenthal. Springer, 1999.

- ^ a b Why do two great tastes sometimes not taste great together? Archived 28 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine scientificamerican.com. Dr. Tim Jacob, Cardiff University. 22 May 2009.

- ^ Miller, Greg (2 September 2011). "Sweet here, salty there: Evidence of a taste map in the mammilian brain". Science. 333 (6047): 1213. Bibcode:2011Sci...333.1213M. doi:10.1126/science.333.6047.1213. PMID 21885750.

- ^ Henry M Seidel; Jane W Ball; Joyce E Dains (1 February 2010). Mosby's Guide to Physical Examination. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 303. ISBN 978-0-323-07357-8.

- ^ Scully, Simone M. (9 June 2014). "The Animals That Taste Only Saltiness". Nautilus. Archived from the original on 14 June 2014. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ^ a b c Ikeda, Kikunae (2002) [1909]. "New Seasonings". Chemical Senses. 27 (9): 847–849. doi:10.1093/chemse/27.9.847. PMID 12438213.; a partial translation from Ikeda, Kikunae (1909). "New Seasonings". Journal of the Chemical Society of Tokyo (in Japanese). 30 (8): 820–836. doi:10.1246/nikkashi1880.30.820. PMID 12438213.

- ^ a b Lindemann, Bernd (13 September 2001). "Receptors and transduction in taste". Nature. 413 (6852): 219–225. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..219L. doi:10.1038/35093032. PMID 11557991. S2CID 4385513.

- ^ Delpire, Eric; Gagnon, Kenneth B. (1 January 2018), Levitane, Irena; Delpire, Eric; Rasgado-Flores, Hector (eds.), "Chapter One - Water Homeostasis and Cell Volume Maintenance and Regulation", Current Topics in Membranes, Cell Volume Regulation, 81, Academic Press: 3–52, doi:10.1016/bs.ctm.2018.08.001, PMC 6457474, PMID 30243436

- ^ Low, Yu; Lacy, Kathleen; Keast, Russell (2 September 2014). "The Role of Sweet Taste in Satiation and Satiety". Nutrients. 6 (9): 3431–3450. doi:10.3390/nu6093431. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 4179169. PMID 25184369.

- ^ Holesh, Julie E.; Aslam, Sanah; Martin, Andrew (2025), "Physiology, Carbohydrates", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29083823, retrieved 1 July 2025

- ^ "Choose your carbs wisely". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 1 July 2025.

- ^ Ayurvedic balancing: an integration of Western fitness with Eastern wellness (Pages 25-26/188) Joyce Bueker. Llewellyn Worldwide, 2002.

- ^ Keast, Russell SJ; Costanzo, Andrew (3 February 2015). "Is fat the sixth taste primary? Evidence and implications". Flavour. 4 5. doi:10.1186/2044-7248-4-5. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30069796. ISSN 2044-7248.

- ^ Running, Cordelia A.; Craig, Bruce A.; Mattes, Richard D. (1 September 2015). "Oleogustus: The Unique Taste of Fat". Chemical Senses. 40 (7): 507–516. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjv036. ISSN 0379-864X. PMID 26142421.

- ^ a b Reed, Danielle R.; Xia, Mary B. (1 May 2015). "Recent Advances in Fatty Acid Perception and Genetics". Advances in Nutrition. 6 (3): 353S – 360S. doi:10.3945/an.114.007005. ISSN 2156-5376. PMC 4424773. PMID 25979508.

- ^ Zhao, Grace Q.; Yifeng Zhang; Mark A. Hoon; Jayaram Chandrashekar; Isolde Erlenbach; Nicholas J.P. Ryba; Charles S. Zuker (October 2003). "The Receptors for Mammalian Sweet and Savory taste". Cell. 115 (3): 255–266. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00844-4. PMID 14636554. S2CID 11773362.

- ^ Juen, Zhang; Lu, Zhengyuan; Yu, Ruihuan; Chang, Andrew N.; Wang, Brian; Fitzpatrick, Anthony W.P.; Zuker, Charles S. (May 2025). "The structure of human sweetness". Cell. 188 (15): 4141–4153.e18. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2025.04.021. PMID 40339580.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Guyton, Arthur C. (1991) Textbook of Medical Physiology. (8th ed). Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders

- ^ a b c d e f g McLaughlin, Susan; Margolskee, Rorbert F. (November–December 1994). "The Sense of Taste". American Scientist. 82 (6): 538–545. Bibcode:1994AmSci..82..538M.

- ^ Rui Chang, Hang Waters & Emily Liman (2010). "A proton current drives action potentials in genetically identified sour taste cells". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107 (51): 22320–22325. Bibcode:2010PNAS..10722320C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1013664107. PMC 3009759. PMID 21098668.

- ^ Tu, YH (2018). "An evolutionarily conserved gene family encodes proton-selective ion channels". Science. 359 (6379): 1047–1050. Bibcode:2018Sci...359.1047T. doi:10.1126/science.aao3264. PMC 5845439. PMID 29371428.

- ^ Ye W, Chang RB, Bushman JD, Tu YH, Mulhall EM, Wilson CE, Cooper AJ, Chick WS, Hill-Eubanks DC, Nelson MT, Kinnamon SC, Liman ER (2016). "The K+ channel KIR2.1 functions in tandem with proton influx to mediate sour taste transduction". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 113 (2): E229–238. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113E.229Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1514282112. PMC 4720319. PMID 26627720.

- ^ Djin Gie Liem & Julie A. Mennella (February 2003). "Heightened Sour Preferences During Childhood". Chem Senses. 28 (2): 173–180. doi:10.1093/chemse/28.2.173. PMC 2789429. PMID 12588738.

- ^ a b c Taruno, Akiyuki; Gordon, Michael D. (10 February 2023). "Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Salt Taste". Annual Review of Physiology. 85 (1): 25–45. doi:10.1146/annurev-physiol-031522-075853. PMID 36332657.

Elahi, Tasnuva (15 September 2023). "Salt Taste Is Surprisingly Mysterious". Nautilus. - ^ Scinska A, Koros E, Habrat B, Kukwa A, Kostowski W, Bienkowski P (August 2000). "Bitter and sweet components of ethanol taste in humans". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 60 (2): 199–206. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(99)00149-0. PMID 10940547.

- ^ a b Logue, Alexandra W. (1986). The Psychology of Eating and Drinking. New York: W.H. Freeman & Co. ISBN 978-0-415-81708-0.[page needed]

- ^ Glendinning, J. I. (1994). "Is the bitter rejection response always adaptive?". Physiol Behav. 56 (6): 1217–1227. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(94)90369-7. PMID 7878094. S2CID 22945002.

- ^ Jones, S., Martin, R., & Pilbeam, D. (1994) The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Human Evolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press[page needed]

- ^ Johns, Timothy (1990). With Bitter Herbs They Shall Eat It: Chemical ecology and the origins of human diet and medicine. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1023-7.[page needed]

- ^ Wang, X. (2004). "Relaxation Of Selective Constraint And Loss Of Function In The Evolution Of Human Bitter Taste Receptor Genes". Human Molecular Genetics. 13 (21): 2671–2678. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh289. PMID 15367488.

- ^ "What is Bitrex?". Bitrex – Keeping children safe. 21 December 2015. Archived from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ^ "Denatonium Benzoate". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Maehashi, K.; Matano, M.; Wang, H.; Vo, L. A.; Yamamoto, Y.; Huang, L. (2008). "Bitter peptides activate hTAS2Rs, the human bitter receptors". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 365 (4): 851–855. Bibcode:2008BBRC..365..851M. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.070. PMC 2692459. PMID 18037373.

- ^ Meyerhof (2010). "The molecular receptive ranges of human TAS2R bitter taste receptors". Chem Senses. 35 (2): 157–70. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjp092. PMID 20022913.

- ^ Wiener (2012). "BitterDB: a database of bitter compounds". Nucleic Acids Res. 40 (Database issue): D413–9. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr755. PMC 3245057. PMID 21940398.

- ^ Wang, X.; Thomas, S. D.; Zhang, J. (2004). "Relaxation of selective constraint and loss of function in the evolution of human bitter taste receptor genes". Hum Mol Genet. 13 (21): 2671–2678. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddh289. PMID 15367488.

- ^ Wooding, S.; Kim, U. K.; Bamshad, M. J.; Larsen, J.; Jorde, L. B.; Drayna, D. (2004). "Natural selection and molecular evolution in PTC, a bitter-taste receptor gene". Am J Hum Genet. 74 (4): 637–646. doi:10.1086/383092. PMC 1181941. PMID 14997422.

- ^ Schmitz, Lea M.; Lang, Tatjana; Steuer, Alexandra; Koppelmann, Luisa; Di Pizio, Antonella; Arnold, Norbert; Behrens, Maik (26 February 2025). "Taste-Guided Isolation of Bitter Compounds from the Mushroom Amaropostia stiptica Activates a Subset of Human Bitter Taste Receptors". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 73 (8): 4850–4858. Bibcode:2025JAFC...73.4850S. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.4c12651. PMC 11869282. PMID 39945763.

- ^ Olias, Gisela. "Mushroom study identifies most bitter substance known to date". Phys.Org. Science X Network. Retrieved 9 April 2025.

- ^ 旨味 definition in English Archived 8 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine Denshi Jisho—Online Japanese dictionary

- ^ "Umami Taste Components and Their Sources in Asian Foods". researchgate.net. 2015.

- ^ a b c "Essiential Ingredients of Japanese Food – Umami". Taste of Japan. Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (Japan). Archived from the original on 16 May 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- ^ Prichep, Deena (26 October 2013). "Fish sauce: An ancient Roman condiment rises again". US National Public Radio. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ^ Butler, Stephanie (20 July 2012). "The Surprisingly Ancient History of Ketchup". HISTORY. Archived from the original on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2022.

- ^ Nelson G, Chandrashekar J, Hoon MA, et al. (March 2002). "An amino-acid taste receptor". Nature. 416 (6877): 199–202. Bibcode:2002Natur.416..199N. doi:10.1038/nature726. PMID 11894099. S2CID 1730089.

- ^ O'Connor, Anahad (10 November 2008). "The Claim: The tongue is mapped into four areas of taste". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 December 2017. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ a b Lindemann, B (February 2000). "A taste for umami". Nature Neuroscience. 3 (2): 99–100. doi:10.1038/72153. PMID 10649560. S2CID 10885181.

- ^ a b c Chaudhari N, Landin AM, Roper SD (February 2000). "A metabotropic glutamate receptor variant functions as a taste receptor". Nature Neuroscience. 3 (2): 113–9. doi:10.1038/72053. PMID 10649565. S2CID 16650588.

- ^ a b Hartley, Isabella E; Liem, Djin Gie; Keast, Russell (16 January 2019). "Umami as an 'Alimentary' Taste. A New Perspective on Taste Classification". Nutrients. 11 (1): 182. doi:10.3390/nu11010182. ISSN 2072-6643. PMC 6356469. PMID 30654496.

- ^ a b Tsai, Michelle (14 May 2007), "How Sweet It Is? Measuring the intensity of sugar substitutes", Slate, The Washington Post Company, archived from the original on 13 August 2010, retrieved 14 September 2010

- ^ Walters, D. Eric (13 May 2008), "How is Sweetness Measured?", All About Sweeteners, archived from the original on 24 December 2010, retrieved 15 September 2010

- ^ a b Joesten, Melvin D; Hogg, John L; Castellion, Mary E (2007), "Sweeteness Relative to Sucrose (table)", The World of Chemistry: Essentials (4th ed.), Belmont, California: Thomson Brooks/Cole, p. 359, ISBN 978-0-495-01213-9, retrieved 14 September 2010

- ^ Coultate, Tom P (2009), "Sweetness relative to sucrose as an arbitrary standard", Food: The Chemistry of its Components (5th ed.), Cambridge, UK: Royal Society of Chemistry, pp. 268–269, ISBN 978-0-85404-111-4, retrieved 15 September 2010

- ^ Mehta, Bhupinder & Mehta, Manju (2005), "Sweetness of sugars", Organic Chemistry, India: Prentice-Hall, p. 956, ISBN 978-81-203-2441-1, retrieved 15 September 2010

- ^ a b c Guyton, Arthur C; Hall, John E. (2006), Guyton and Hall Textbook of Medical Physiology (11th ed.), Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders, p. 664, ISBN 978-0-7216-0240-0

- ^ Food Chemistry (Page 38/1070) H. D. Belitz, Werner Grosch, Peter Schieberle. Springer, 2009.

- ^ a b c Quality control methods for medicinal plant materials, Pg. 38 World Health Organization, 1998.

- ^ David V. Smith, Robert F. Margolskee: Making Sense of Taste Archived 29 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine (Scientific American, September 1, 2006)

- ^ How the Taste Bud Translates Between Tongue and Brain Archived 5 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine nytimes.com, 4 August 1992.

- ^ Zhao GQ, Zhang Y, Hoon MA, et al. (October 2003). "The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste". Cell. 115 (3): 255–66. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00844-4. PMID 14636554. S2CID 11773362.

- ^ a b c channels in sensory cells (Page 155/304) Stephan Frings, Jonathan Bradley. Wiley-VCH, 2004.

- ^ outlines of chemistry with practical work (Page 241) Henry John Horstman Fenton. CUP Archive.

- ^ Focus Ace Pmr 2009 Science (Page 242/522) Chang See Leong, Chong Kum Ying, Choo Yan Tong & Low Swee Neo. Focus Ace Pmr 2009 Science.

- ^ "Biologists Discover How We Detect Sour Taste", Science Daily, 24 August 2006, archived from the original on 30 October 2009, retrieved 12 September 2010

- ^ Maehashi K, Matano M, Wang H, Vo LA, Yamamoto Y, Huang L (January 2008). "Bitter peptides activate hTAS2Rs, the human bitter receptors". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 365 (4): 851–5. Bibcode:2008BBRC..365..851M. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.070. PMC 2692459. PMID 18037373.

- ^ Lindemann, B (September 2001). "Receptors and transduction in taste". Nature. 413 (6852): 219–25. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..219L. doi:10.1038/35093032. PMID 11557991. S2CID 4385513.

- ^ a b What Is Umami?: What Exactly is Umami? Archived 23 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine Umami Information Center

- ^ Chandrashekar, Jayaram; Hoon, Mark A; Ryba, Nicholas J. P. & Zuker, Charles S (16 November 2006), "The receptors and cells for mammalian taste" (PDF), Nature, 444 (7117): 288–294, Bibcode:2006Natur.444..288C, doi:10.1038/nature05401, PMID 17108952, S2CID 4431221, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011, retrieved 13 September 2010

- ^ a b What Is Umami?: The Composition of Umami Archived 27 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine Umami Information Center

- ^ Katzer, Gernot. "Spice Pages: Sichuan Pepper (Zanthoxylum, Szechwan peppercorn, fagara, hua jiao, sansho 山椒, timur, andaliman, tirphal)". gernot-katzers-spice-pages.com. Archived from the original on 19 November 2012. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- ^ Peleg, Hanna; Gacon, Karine; Schlich, Pascal; Noble, Ann C (June 1999). "Bitterness and astringency of flavan-3-ol monomers, dimers and trimers". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 79 (8): 1123–1128. Bibcode:1999JSFA...79.1123P. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199906)79:8<1123::AID-JSFA336>3.0.CO;2-D.

- ^ "Could your mouth charge your iPhone?". kcdentalworks.com. 24 April 2019. Archived from the original on 3 May 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Riera, Céline E.; Vogel, Horst; Simon, Sidney A.; le Coutre, Johannes (2007). "Artificial sweeteners and salts producing a metallic taste sensation activate TRPV1 receptors". American Journal of Physiology. 293 (2): R626 – R634. doi:10.1152/ajpregu.00286.2007. PMID 17567713.

- ^ Willard, James P. (1905). "Current Events". Progress: A Monthly Journal Devoted to Medicine and Surgery. 4: 861–68.

- ^ Monosson, Emily (2012). Evolution in a Toxic World: How Life Responds to Chemical Threats. Island Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-59726-976-6.

- ^ a b Goldstein, E. Bruce (2010). Encyclopedia of Perception. Vol. 2. SAGE. pp. 958–59. ISBN 978-1-4129-4081-8.

- ^ Levy, René H. (2002). Antiepileptic Drugs. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 875. ISBN 978-0-7817-2321-3.

- ^ Reith, Alastair J. M.; Spence, Charles (2020). "The mystery of "metal mouth" in chemotherapy". Chemical Senses. 45 (2): 73–84. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjz076. PMID 32211901. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Stellman, Jeanne Mager (1998). Encyclopaedia of Occupational Health and Safety: The body, health care, management and policy, tools and approaches. International Labour Organization. p. 299. ISBN 978-92-2-109814-0.

- ^ Biello, David. "Potential Taste Receptor for Fat Identified". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Laugerette, F; Passilly-Degrace, P; Patris, B; Niot, I; Febbraio, M; Montmayeur, J. P.; Besnard, P (2005). "CD36 involvement in orosensory detection of dietary lipids, spontaneous fat preference, and digestive secretions". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 115 (11): 3177–84. doi:10.1172/JCI25299. PMC 1265871. PMID 16276419.

- ^ Dipatrizio, N. V. (2014). "Is fat taste ready for primetime?". Physiology & Behavior. 136C: 145–154. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.03.002. PMC 4162865. PMID 24631296.

- ^ Baillie, A. G.; Coburn, C. T.; Abumrad, N. A. (1996). "Reversible binding of long-chain fatty acids to purified FAT, the adipose CD36 homolog". The Journal of Membrane Biology. 153 (1): 75–81. doi:10.1007/s002329900111. PMID 8694909. S2CID 5911289.

- ^ Simons, P. J.; Kummer, J. A.; Luiken, J. J.; Boon, L (2011). "Apical CD36 immunolocalization in human and porcine taste buds from circumvallate and foliate papillae". Acta Histochemica. 113 (8): 839–43. doi:10.1016/j.acthis.2010.08.006. PMID 20950842.

- ^ a b Mattes, R. D. (2011). "Accumulating evidence supports a taste component for free fatty acids in humans". Physiology & Behavior. 104 (4): 624–31. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.05.002. PMC 3139746. PMID 21557960.

- ^ Pepino, M. Y.; Love-Gregory, L; Klein, S; Abumrad, N. A. (2012). "The fatty acid translocase gene CD36 and lingual lipase influence oral sensitivity to fat in obese subjects". The Journal of Lipid Research. 53 (3): 561–6. doi:10.1194/jlr.M021873. PMC 3276480. PMID 22210925.

- ^ Kimura I, Ichimura A, Ohue-Kitano R, Igarashi M (January 2020). "Free Fatty Acid Receptors in Health and Disease". Physiological Reviews. 100 (1): 171–210. doi:10.1152/physrev.00041.2018. PMID 31487233.

- ^ Cartoni, C; Yasumatsu, K; Ohkuri, T; Shigemura, N; Yoshida, R; Godinot, N; Le Coutre, J; Ninomiya, Y; Damak, S (2010). "Taste preference for fatty acids is mediated by GPR40 and GPR120". Journal of Neuroscience. 30 (25): 8376–82. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0496-10.2010. PMC 6634626. PMID 20573884.

- ^ Liu, P; Shah, B. P.; Croasdell, S; Gilbertson, T. A. (2011). "Transient receptor potential channel type M5 is essential for fat taste". Journal of Neuroscience. 31 (23): 8634–42. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6273-10.2011. PMC 3125678. PMID 21653867.

- ^ Running, Cordelia A.; Craig, Bruce A.; Mattes, Richard D. (3 July 2015). "Oleogustus: The Unique Taste of Fat". Chemical Senses. 40 (6): 507–516. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjv036. PMID 26142421.

- ^ Neubert, Amy Patterson (23 July 2015). "Research confirms fat is sixth taste; names it oleogustus". Purdue News. Purdue University. Archived from the original on 8 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ Keast, Russell (3 February 2015). "Is fat the sixth taste primary? Evidence and implications". Flavour. Vol. 4. doi:10.1186/2044-7248-4-5.

- ^ Feldhausen, Teresa Shipley (31 July 2015). "The five basic tastes have sixth sibling: oleogustus". Science News. Archived from the original on 16 August 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ^ a b Nishimura, Toshihide; Egusa, Ai (20 January 2016). ""Koku" Involved in Food Palatability: An Overview of Pioneering Work and Outstanding Questions" 食べ物の「こく」を科学するその現状と展望. Kagaku to Seibutsu (in Japanese). Vol. 2, no. 54. Japan Society for Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Agrochemistry (JSBBA). pp. 102–108. doi:10.1271/kagakutoseibutsu.54.102. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

「こく」appears in abstract. 「コク味物質」appears in p106 1.b

- ^ a b Hettiarachchy, Navam S.; Sato, Kenji; Marshall, Maurice R., eds. (2010). Food proteins and peptides: chemistry, functionality interactions, and commercialization. Boca Raton, Fla.: CRC. ISBN 978-1-4200-9341-4. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ a b Ueda, Yoichi; Sakaguchi, Makoto; Hirayama, Kazuo; Miyajima, Ryuichi; Kimizuka, Akimitsu (1990). "Characteristic Flavor Constituents in Water Extract of Garlic". Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 54 (1): 163–169. doi:10.1080/00021369.1990.10869909.

- ^ Eto, Yuzuru; Kuroda, Motonaka; Yasuda, Reiko; Maruyama, Yutaka (12 April 2012). "Kokumi Substances, Enhancers of Basic Tastes, Induce Responses in Calcium-Sensing Receptor Expressing Taste Cells". PLOS ONE. 7 (4) e34489. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...734489M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034489. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3325276. PMID 22511946.

- ^ Eto, Yuzuru; Miyamura, Naohiro; Maruyama, Yutaka; Hatanaka, Toshihiro; Takeshita, Sen; Yamanaka, Tomohiko; Nagasaki, Hiroaki; Amino, Yusuke; Ohsu, Takeaki (8 January 2010). "Involvement of the Calcium-sensing Receptor in Human Taste Perception". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 285 (2): 1016–1022. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109.029165. ISSN 0021-9258. PMC 2801228. PMID 19892707.

- ^ "Like the Taste of Chalk? You're in Luck—Humans May Be Able to Taste Calcium". Scientific American. 20 August 2008. Archived from the original on 28 March 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ^ Tordorf, Michael G. (2008), "Chemosensation of Calcium", American Chemical Society National Meeting, Fall 2008, 236th, Philadelphia, PA: American Chemical Society, AGFD 207, archived from the original on 25 August 2009, retrieved 27 August 2008

- ^ "That Tastes ... Sweet? Sour? No, It's Definitely Calcium!", Science Daily, 21 August 2008, archived from the original on 18 October 2009, retrieved 14 September 2010

- ^ Lapis, Trina J.; Penner, Michael H.; Lim, Juyun (23 August 2016). "Humans Can Taste Glucose Oligomers Independent of the hT1R2/hT1R3 Sweet Taste Receptor" (PDF). Chemical Senses. 41 (9): 755–762. doi:10.1093/chemse/bjw088. ISSN 0379-864X. PMID 27553043. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ^ Pullicin, Alexa J.; Penner, Michael H.; Lim, Juyun (29 August 2017). "Human taste detection of glucose oligomers with low degree of polymerization". PLOS ONE. 12 (8) e0183008. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1283008P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0183008. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5574539. PMID 28850567.

- ^ Hamzelou, Jessica (2 September 2016). "There is now a sixth taste – and it explains why we love carbs". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 14 September 2016.

- ^ Eliav, Eli, and Batya Kamran. "Evidence of Chorda Tympani Dysfunction in Patients with Burning Mouth Syndrome." Science Direct. May 2007. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Mu, Liancai, and Ira Sanders. "Human Tongue Neuroanatomy: Nerve Supply and Motor Endplates." Wiley Online Library. Oct. 2010. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ King, Camillae T., and Susan P. Travers. "Glossopharyngeal Nerve Transection Eliminates Quinine-Stimulated Fos-Like Immunoreactivity in the Nucleus of the Solitary Tract: Implications for a Functional Topography of Gustatory Nerve Input in Rats." JNeurosci. 15 April 1999. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Hornung, Jean-Pierre. "The Human Raphe Nuclei and the Serotonergic System."Science Direct. Dec. 2003. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Reiner, Anton, and Harvey J. Karten. "Parasympathetic Ocular Control — Functional Subdivisions and Circuitry of the Avian Nucleus of Edinger-Westphal."Science Direct. 1983. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Wright, Christopher I., and Brain Martis. "Novelty Responses and Differential Effects of Order in the Amygdala, Substantia Innominata, and Inferior Temporal Cortex." Science Direct. Mar. 2003. Web. 27 March 2016.

- ^ Menon, Vinod, and Lucina Q. Uddin. "Saliency, Switching, Attention and Control: A Network Model of Insula." Springer. 29 May 2010. Web. 28 March 2016.

- ^ Bartoshuk L. M.; Duffy V. B.; et al. (1994). "PTC/PROP tasting: anatomy, psychophysics, and sex effects." 1994". Physiol Behav. 56 (6): 1165–71. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(94)90361-1. PMID 7878086. S2CID 40598794.

- ^ Gardner, Amanda (16 June 2010). "Love salt? You might be a 'supertaster'". CNN Health. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- ^ Walker, H. Kenneth (1990). "Cranial Nerve VII: The Facial Nerve and Taste". Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. Butterworths. ISBN 978-0-409-90077-4. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ^ Meunier, Nicolas; Briand, Loïc; Jacquin-Piques, Agnès; Brondel, Laurent; Pénicaud, Luc (2020). "COVID 19-Induced Smell and Taste Impairments: Putative Impact on Physiology". Frontiers in Physiology. 11 625110. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.625110. ISSN 1664-042X. PMC 7870487. PMID 33574768.

- ^ Veronese, Sheila; Sbarbati, Andrea (3 March 2021). "Chemosensory Systems in COVID-19: Evolution of Scientific Research". ACS Chemical Neuroscience. 12 (5): 813–824. doi:10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00788. ISSN 1948-7193. PMC 7885804. PMID 33559466.

- ^ On the Soul Archived 6 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine Aristotle. Translated by J. A. Smith. The Internet Classics Archive.

- ^ Aristotle's De anima (422b10-16) Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine Ronald M. Polansky. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- ^ Origins of neuroscience: a history of explorations into brain function (Page 165/480) Archived 26 March 2023 at the Wayback Machine Stanley Finger. Oxford University Press US, 2001.

- ^ a b Bachmanov, AA.; Beauchamp, GK. (2007). "Taste receptor genes". Annu Rev Nutr. 27 (1): 389–414. doi:10.1146/annurev.nutr.26.061505.111329. PMC 2721271. PMID 17444812.

- ^ Kinnamon SC, Finger TE (2019). "Recent advances in taste transduction and signaling". F1000Research. 8: 2117. doi:10.12688/f1000research.21099.1. PMC 7059786. PMID 32185015.

- ^ Guyton, Arthur C. (1976), Textbook of Medical Physiology (5th ed.), Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, p. 839, ISBN 978-0-7216-4393-9

- ^ Macbeth, Helen M.; MacClancy, Jeremy, eds. (2004), "plethora of methods characterising human taste perception", Researching Food Habits: Methods and Problems, The anthropology of food and nutrition, vol. 5, New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 87–88, ISBN 978-1-57181-544-6, retrieved 15 September 2010

- ^ Svrivastava, R. C. & Rastogi, R. P. (2003). "Relative taste indices of some substances". Transport Mediated by Electrical Interfaces. Studies in interface science 18. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-444-51453-0. Retrieved 12 September 2010. Taste indices of table 9, p. 274 are select sample taken from table in Guyton's Textbook of Medical Physiology (present in all editions.

Further reading

[edit]- Chandrashekar, Jayaram; Hoon, Mark A.; Ryba; Nicholas, J. P. & Zuker, Charles S. (16 November 2006). "The receptors and cells for mammalian taste" (PDF). Nature. 444 (7117): 288–294. Bibcode:2006Natur.444..288C. doi:10.1038/nature05401. PMID 17108952. S2CID 4431221. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- Chaudhari, Nirupa & Roper, Stephen D. (2010). "The cell biology of taste". Journal of Cell Biology. 190 (3): 285–296. doi:10.1083/jcb.201003144. PMC 2922655. PMID 20696704.