Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fructose

View on Wikipedia

| |||

Haworth projection of β-d-fructofuranose

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

D-arabino-Hex-2-ulose[3]

| |||

| Systematic IUPAC name

(3S,4R,5R)-1,3,4,5,6-Pentahydroxyhexan-2-one | |||

| Other names | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.303 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| C6H12O6 | |||

| Molar mass | 180.156 g·mol−1 | ||

| Density | 1.694 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | 103 °C (217 °F; 376 K) | ||

| ~4000 g/L (25 °C) | |||

| −102.60×10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

675.6 kcal/mol (2,827 kJ/mol)[4] (Higher heating value) | ||

| Pharmacology | |||

| V06DC02 (WHO) | |||

| Hazards | |||

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |||

LD50 (median dose)

|

15000 mg/kg (intravenous, rabbit)[5] | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

Fructose (/ˈfrʌktoʊs, -oʊz/), or fruit sugar, is a common monosaccharide, i.e. a simple sugar. It is classified as a reducing hexose, more specifically a ketonic simple sugar found in many plants, where it is often bonded to glucose to form the disaccharide sucrose. In terms of structure, it is a C-4 epimer of glucose. A white, water-soluble solid,It is one of the three dietary monosaccharides, along with glucose and galactose.[6] Fructose is found in honey, tree and vine fruits, flowers, berries, and most root vegetables.

History

[edit]Fructose was discovered by French chemist Augustin-Pierre Dubrunfaut in 1847.[7][8] The name "fructose" was coined in 1857 by the English chemist William Allen Miller.[9] Pure, dry fructose is a sweet, white, odorless, crystalline solid, and is the most water-soluble of all the sugars.[10]

Etymology

[edit]The word "fructose" was coined in 1857 from the Latin for fructus (fruit) and the generic chemical suffix for sugars, -ose.[9][11] It is also called fruit sugar and levulose or laevulose, due to its ability to rotate plane polarised light in a laevorotary fashion (anti-clockwise/to the left) when a beam is shone through it in solution. Likewise, dextrose (an isomer of glucose) is given its name due to its ability to rotate plane polarised light in a dextrorotary fashion (clockwise/to the right).[11]

Chemical structure

[edit]

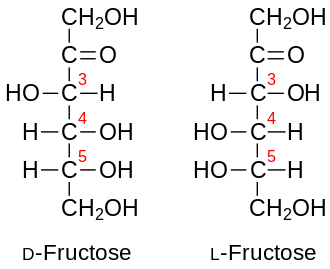

Fructose adopts both cyclic six- and five-membered structure, The six membered ring can exist as either the β-d-fructopyranose and α-d-fructopyranose. The five-membered rings exists as either of two isomers β-d-fructofuranose and α-d-fructofuranose. Additionally, an acyclic (open-chain) form exists: keto-d-fructose.[12][13] At 70% and 22% respectively, fructopyranose and fructofuranose are the dominant species in aqueous solution.[14]

Chemical reactions

[edit]Fructose and fermentation

[edit]Fructose may be anaerobically fermented by yeast and bacteria.[15] Yeast enzymes convert sugar (sucrose, glucose, and fructose, but not lactose) to ethanol and carbon dioxide.[16] Some of the carbon dioxide produced during fermentation will remain dissolved in water, where it will reach equilibrium with carbonic acid. The dissolved carbon dioxide and carbonic acid produce the carbonation in some fermented beverages, such as champagne.

Fructose and Maillard reaction

[edit]Fructose undergoes the Maillard reaction, non-enzymatic browning, with amino acids. Because fructose exists to a greater extent in the open-chain form than does glucose, the initial stages of the Maillard reaction occur more rapidly than with glucose. Therefore, fructose has potential to contribute to changes in food palatability, as well as other nutritional effects, such as excessive browning, volume and tenderness reduction during cake preparation, and formation of mutagenic compounds.[17]

Dehydration

[edit]Fructose can be dehydrated to give hydroxymethylfurfural ("HMF", C

6H

6O

3), which can be processed into liquid dimethylfuran (C

6H

8O).

This conversion has long been proposed, not implemented, as a route to green fuels.[18]

Physical and functional properties

[edit]Sweetness of fructose

[edit]The primary reason that fructose is used commercially in foods and beverages, besides its low cost, is its high relative sweetness. It is the sweetest of all naturally occurring carbohydrates. The relative sweetness of fructose has been reported in the range of 1.2–1.8 times that of sucrose.[19][20][21][22] However, it is the 6-membered ring form of fructose that is sweeter; the 5-membered ring form tastes about the same as usual table sugar. Warming fructose leads to formation of the 5-membered ring form.[23] Therefore, the relative sweetness decreases with increasing temperature. However, it has been observed that the absolute sweetness of fructose is identical at 5 °C as 50 °C and thus the relative sweetness to sucrose is not due to anomeric distribution but a decrease in the absolute sweetness of sucrose at higher temperatures.[21]

The sweetness of fructose is perceived earlier than that of sucrose or glucose, and the taste sensation reaches a peak (higher than that of sucrose), and diminishes more quickly than that of sucrose. Fructose can also enhance other flavors in the system.[19][21]

Fructose exhibits a sweetness synergy effect when used in combination with other sweeteners. The relative sweetness of fructose blended with sucrose, aspartame, or saccharin is perceived to be greater than the sweetness calculated from individual components.[24][21]

Fructose solubility and crystallization

[edit]Fructose has higher water solubility than other sugars, as well as other sugar alcohols. Fructose is, therefore, difficult to crystallize from an aqueous solution.[19] Sugar mixes containing fructose, such as candies, are softer than those containing other sugars because of the greater solubility of fructose.[25]

Fructose hygroscopicity and humectancy

[edit]Fructose is quicker to absorb moisture and slower to release it to the environment than sucrose, glucose, or other nutritive sweeteners.[24] Fructose is an excellent humectant and retains moisture for a long period of time even at low relative humidity (RH). Therefore, fructose can contribute a more palatable texture, and longer shelf life to the food products in which it is used.[19]

Freezing point

[edit]Fructose has a greater effect on freezing point depression than disaccharides or oligosaccharides, which may protect the integrity of cell walls of fruit by reducing ice crystal formation. However, this characteristic may be undesirable in soft-serve or hard-frozen dairy desserts.[19]

Fructose and starch functionality in food systems

[edit]Fructose increases starch viscosity more rapidly and achieves a higher final viscosity than sucrose because fructose lowers the temperature required during gelatinizing of starch, causing a greater final viscosity.[26]

Although some artificial sweeteners are not suitable for home baking, many traditional recipes use fructose.[27]

Sources

[edit]

Commercial production

[edit]Fructose is produced on an industrial scale from three precursors: starch, sucrose, and inulin. Sucrose is an organic compound with one molecule of glucose covalently linked to one molecule of fructose. All forms of fructose, including those found in fruits and juices, are commonly added to foods and drinks for palatability and taste enhancement, and for browning of some foods, such as baked goods. [6] Fructose is found in honey, tree and vine fruits, flowers, berries, and most root vegetables.

Starch is hydrolyzed to glucose, which is converted to fructose by the enzyme glucose isomerase. This mixture is high-fructose corn syrup. At 60 °C, the conversion gives a 1:1 mixture of glucose and fructose. Sucrose is hydrolyzed to give its monomeric precursors glucose and fructose. Inulin is also converted to fructose on a commercial scale. As of 2004, about 240,000 tonnes of crystalline fructose were being produced annually.[6]Commercially, maize is a major source of starch. Sugar cane and sugar beets are sources of sucrose is a compound with one molecule of glucose covalently linked to one molecule of fructose. Inulin is found in chicory,

All forms of fructose, including those found in fruits and juices, are commonly added to foods and drinks for palatability and taste enhancement, and for browning of some foods, such as baked goods.

Natural sources

[edit]Natural sources of fructose include fruits, vegetables (including sugar cane), and honey.[28] Fructose is often further concentrated from these sources. The highest dietary sources of fructose, besides pure crystalline fructose, are foods containing white sugar (sucrose), high-fructose corn syrup, agave nectar, honey, molasses, maple syrup, fruit and fruit juices, as these have the highest percentages of fructose (including fructose in sucrose) per serving compared to other common foods and ingredients. Fructose exists in foods either as a free monosaccharide or bound to glucose as sucrose, a disaccharide. Fructose, glucose, and sucrose may all be present in food; however, different foods will have varying levels of each of these three sugars.

The sugar contents of common fruits and vegetables are presented in Table 1. In general, in foods that contain free fructose, the ratio of fructose to glucose is approximately 1:1; that is, foods with fructose usually contain about an equal amount of free glucose. A value that is above 1 indicates a higher proportion of fructose to glucose and below 1 a lower proportion. Some fruits have larger proportions of fructose to glucose compared to others. For example, apples and pears contain more than twice as much free fructose as glucose, while for apricots the proportion is less than half as much fructose as glucose.

Apple and pear juices are of particular interest to pediatricians because the high concentrations of free fructose in these juices can cause diarrhea in children. The cells (enterocytes) that line children's small intestines have less affinity for fructose absorption than for glucose and sucrose.[29] Unabsorbed fructose creates higher osmolarity in the small intestine, which draws water into the gastrointestinal tract, resulting in osmotic diarrhea. This phenomenon is discussed in greater detail in the Health Effects section.

Table 1 also shows the amount of sucrose found in common fruits and vegetables. Sugarcane and sugar beet have a high concentration of sucrose, and are used for commercial preparation of pure sucrose. Extracted cane or beet juice is clarified, removing impurities; and concentrated by removing excess water. The end product is 99.9%-pure sucrose. Sucrose-containing sugars include common white sugar and powdered sugar, as well as brown sugar.[30]

| Food Item | Total carbohydrateA including "dietary fiber" |

Total sugars |

Free fructose |

Free glucose |

Sucrose | Fructose/ glucose ratio |

Sucrose as a % of total sugars |

Free fructose as a % of total sugars |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruits | ||||||||

| Apple | 13.8 | 10.4 | 5.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.0? | 19.9 | 57 |

| Apricot | 11.1 | 9.2 | 0.9 | 2.4 | 5.9 | 0.7? | 63.5 | 10 |

| Banana | 22.8 | 12.2 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 20.0 | 40 |

| Fig, dried | 63.9 | 47.9 | 22.9 | 24.8 | 0.9? | 0.93 | 1.9 | 47.8 |

| Grapes | 18.1 | 15.5 | 8.1 | 7.2 | 0.2 | 1.1 | 1 | 52 |

| Navel orange | 12.5 | 8.5 | 2.25 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 1.1 | 50.4 | 26 |

| Peach | 9.5 | 8.4 | 1.5 | 2.0 | 4.8 | 0.9? | 56.7 | 18 |

| Pear | 15.5 | 9.8 | 6.2 | 2.8 | 0.8 | 2.1? | 8.0 | 63 |

| Pineapple | 13.1 | 9.9 | 2.1 | 1.7 | 6.0 | 1.1 | 60.8 | 21 |

| Plum | 11.4 | 9.9 | 3.1 | 5.1 | 1.6 | 0.66 | 16.2 | 31 |

| Vegetables | ||||||||

| Beet, Red | 9.6 | 6.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 6.5 | 1.0 | 96.2 | 1.5 |

| Carrot | 9.6 | 4.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 3.6 | 1.0 | 77 | 13 |

| Red Pepper, Sweet | 6.0 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 55 |

| Onion, Sweet | 7.6 | 5.0 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 14.3 | 40 |

| Sweet Potato | 20.1 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.9 | 60.3 | 17 |

| Yam | 27.9 | 0.5 | tr | tr | tr | na | tr | |

| Sugar Cane | 13–18 | 0.2 – 1.0 | 0.2 – 1.0 | 11–16 | 1.0 | high | 1.5-5.6 | |

| Sugar Beet | 17–18 | 0.1 – 0.5 | 0.1 – 0.5 | 16–17 | 1.0 | high | 0.59-2.8 | |

| Grains | ||||||||

| Maize, Sweet | 19.0 | 6.2 | 1.9 | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.61 | 15.0 | 31 |

- ^A The carbohydrate figure is calculated in FoodData Central and does not always correspond to the sum of the sugars, the starch, and the "dietary fiber".

All data with a unit of g (gram) are based on 100 g of a food item. The fructose/glucose ratio is calculated by dividing the sum of free fructose plus half sucrose by the sum of free glucose plus half sucrose.

Fructose is also found in the manufactured sweetener, high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), which is produced by treating corn syrup with enzymes, converting glucose into fructose.[32] The common designations for fructose content, HFCS-42 and HFCS-55, indicate the percentage of fructose present in HFCS.[32] HFCS-55 is commonly used as a sweetener for soft drinks, whereas HFCS-42 is used to sweeten processed foods, breakfast cereals, bakery foods, and some soft drinks.[32]

Carbohydrate content of commercial sweeteners (percent on dry basis)

[edit]| Sugar | Fructose | Glucose | Sucrose (Fructose+Glucose) |

Other sugars |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Granulated sugar | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 |

| Caramel | 1 | 1 | 97 | 1 |

| HFCS-42 | 42 | 53 | 0 | 5 |

| HFCS-55 | 55 | 41 | 0 | 4 |

| HFCS-90 | 90 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Honey | 50 | 44 | 1 | 5 |

| Maple syrup | 1 | 4 | 95 | 0 |

| Molasses | 23 | 21 | 53 | 3 |

| Tapioca Syrup | 55 | 45 | 0 | 0 |

| Corn syrup | 0 | 98 | 0 | 2 |

[30] for HFCS, and USDA for fruits and vegetables and the other refined sugars.[31]

Cane and beet sugars have been used as the major sweetener in food manufacturing for centuries. However, with the development of HFCS, a significant shift occurred in the type of sweetener consumption in certain countries, particularly the United States.[33] Contrary to the popular belief, however, with the increase of HFCS consumption, the total fructose intake relative to the total glucose intake has not dramatically changed. Granulated sugar is 99.9%-pure sucrose, which means that it has equal ratio of fructose to glucose. The most commonly used forms of HFCS, HFCS-42, and HFCS-55, have a roughly equal ratio of fructose to glucose, with minor differences. HFCS has simply replaced sucrose as a sweetener. Therefore, despite the changes in the sweetener consumption, the ratio of glucose to fructose intake has remained relatively constant.[34]

Nutritional information

[edit]Providing 368 kcal per 100 grams of dry powder (table), fructose has 95% the caloric value of sucrose by weight.[35][36] Fructose powder is 100% carbohydrates and supplies no other nutrients in significant amount (table).

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 368 kcal (1,540 kJ) | ||||||||||||||||||

100 g | |||||||||||||||||||

0 g | |||||||||||||||||||

0 g | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[37] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[38] | |||||||||||||||||||

Fructose digestion and absorption in humans

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2020) |

Fructose exists in foods either as a monosaccharide (free fructose) or as a unit of a disaccharide (sucrose). Free fructose is a ketonic simple sugar and one of the three dietary monosaccharides absorbed directly by the intestine. When fructose is consumed in the form of sucrose, it is digested (broken down) and then absorbed as free fructose. As sucrose comes into contact with the membrane of the small intestine, the enzyme sucrase catalyzes the cleavage of sucrose to yield one glucose unit and one fructose unit, which are then each absorbed. After absorption, it enters the hepatic portal vein and is directed toward the liver.

The mechanism of fructose absorption in the small intestine is not completely understood. Some evidence suggests active transport, because fructose uptake has been shown to occur against a concentration gradient.[39] However, the majority of research supports the claim that fructose absorption occurs on the mucosal membrane via facilitated transport involving GLUT5 transport proteins.[40] Since the concentration of fructose is higher in the lumen, fructose is able to flow down a concentration gradient into the enterocytes, assisted by transport proteins. Fructose may be transported out of the enterocyte across the basolateral membrane by either GLUT2 or GLUT5, although the GLUT2 transporter has a greater capacity for transporting fructose, and, therefore, the majority of fructose is transported out of the enterocyte through GLUT2.[40]

Capacity and rate of absorption

[edit]The absorption capacity for fructose in monosaccharide form ranges from less than 5 g to 50 g (per individual serving) and adapts with changes in dietary fructose intake.[41] Studies show the greatest absorption rate occurs when glucose and fructose are administered in equal quantities.[41] When fructose is ingested as part of the disaccharide sucrose, absorption capacity is much higher because fructose exists in a 1:1 ratio with glucose. It appears that the GLUT5 transfer rate may be saturated at low levels, and absorption is increased through joint absorption with glucose.[42] One proposed mechanism for this phenomenon is a glucose-dependent cotransport of fructose. In addition, fructose transfer activity increases with dietary fructose intake. The presence of fructose in the lumen causes increased mRNA transcription of GLUT5, leading to increased transport proteins. High-fructose diets (>2.4 g/kg body wt) increase the transport proteins within three days of intake.[43]

Malabsorption

[edit]Several studies have measured the intestinal absorption of fructose using the hydrogen breath test.[44][45][46][47] These studies indicate that fructose is not completely absorbed in the small intestine. When fructose is not absorbed in the small intestine, it is transported into the large intestine, where it is fermented by the colonic flora. Hydrogen is produced during the fermentation process and dissolves into the blood of the portal vein. This hydrogen is transported to the lungs, where it is exchanged across the lungs and is measurable by the hydrogen breath test. The colonic flora also produces carbon dioxide, short-chain fatty acids, organic acids, and trace gases in the presence of unabsorbed fructose.[48] The presence of gases and organic acids in the large intestine causes gastrointestinal symptoms such as bloating, diarrhea, flatulence, and gastrointestinal pain.[44] Exercise immediately after consumption can exacerbate these symptoms by decreasing transit time in the small intestine, resulting in a greater amount of fructose emptied into the large intestine.[49]

Fructose metabolism

[edit]The liver converts most fructose and galactose into glucose for distribution in the bloodstream or deposition into glycogen.[50]

All three dietary monosaccharides are transported into the liver by the GLUT2 transporter.[51] Fructose and galactose are phosphorylated in the liver by fructokinase (Km= 0.5 mM) and galactokinase (Km = 0.8 mM), respectively. By contrast, glucose tends to pass through the liver (Km of hepatic glucokinase = 10 mM) and can be metabolised anywhere in the body. Uptake of fructose by the liver is not regulated by insulin. However, insulin is capable of increasing the abundance and functional activity of GLUT5, fructose transporter, in skeletal muscle cells.[52]

Fructolysis

[edit]The initial catabolism of fructose is sometimes referred to as fructolysis, in analogy with glycolysis, the catabolism of glucose. In fructolysis, the enzyme fructokinase initially produces fructose 1-phosphate, which is split by aldolase B to produce the trioses dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde. Unlike glycolysis, in fructolysis the triose glyceraldehyde lacks a phosphate group. A third enzyme, triokinase, is therefore required to phosphorylate glyceraldehyde, producing glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. The resulting trioses are identical to those obtained in glycolysis and can enter the gluconeogenic pathway for glucose or glycogen synthesis, or be further catabolized through the lower glycolytic pathway to pyruvate.

Metabolism of fructose to DHAP and glyceraldehyde

[edit]The first step in the metabolism of fructose is the phosphorylation of fructose to fructose 1-phosphate by fructokinase, thus trapping fructose for metabolism in the liver. Fructose 1-phosphate then undergoes hydrolysis by aldolase B to form DHAP and glyceraldehydes; DHAP can either be isomerized to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate by triosephosphate isomerase or undergo reduction to glycerol 3-phosphate by glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The glyceraldehyde produced may also be converted to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate by glyceraldehyde kinase or further converted to glycerol 3-phosphate by glycerol 3-phosphate dehydrogenase. The metabolism of fructose at this point yields intermediates in the gluconeogenic pathway leading to glycogen synthesis as well as fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis.

Synthesis of glycogen from DHAP and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

[edit]The resultant glyceraldehyde formed by aldolase B then undergoes phosphorylation to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate. Increased concentrations of DHAP and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate in the liver drive the gluconeogenic pathway toward glucose and subsequent glycogen synthesis.[53] It appears that fructose is a better substrate for glycogen synthesis than glucose and that glycogen replenishment takes precedence over triglyceride formation.[54] Once liver glycogen is replenished, the intermediates of fructose metabolism are primarily directed toward triglyceride synthesis.[55]

Synthesis of triglyceride from DHAP and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

[edit]Carbons from dietary fructose are found in both the free fatty acid and glycerol moieties of plasma triglycerides. High fructose consumption can lead to excess pyruvate production, causing a buildup of Krebs cycle intermediates.[56] Accumulated citrate can be transported from the mitochondria into the cytosol of hepatocytes, converted to acetyl CoA by citrate lyase and directed toward fatty acid synthesis.[56][57] In addition, DHAP can be converted to glycerol 3-phosphate, providing the glycerol backbone for the triglyceride molecule.[57] Triglycerides are incorporated into very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), which are released from the liver destined toward peripheral tissues for storage in both fat and muscle cells.

Potential health effects

[edit]In 2022, the European Food Safety Authority stated that there is research evidence that fructose and other added free sugars may be associated with increased risk of several chronic diseases:[58][59] the risk is moderate for obesity and dyslipidemia (more than 50%), and low for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, type 2 diabetes (from 15% to 50%) and hypertension. EFSA further stated that clinical research did "not support a positive relationship between the intake of dietary sugars, in isocaloric exchange with other macronutrients, and any of the chronic metabolic diseases or pregnancy-related endpoints assessed" but advised "the intake of added and free sugars should be as low as possible in the context of a nutritionally adequate diet."[59]

Obesity

[edit]Excessive consumption of sugars, including fructose, contributes to insulin resistance, obesity, elevated LDL cholesterol and triglycerides, leading to metabolic syndrome. The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) stated in 2011 that fructose may be preferable over sucrose and glucose in sugar-sweetened foods and beverages because of its lower effect on postprandial blood sugar levels,[58] while also noting the potential downside that "high intakes of fructose may lead to metabolic complications such as dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, and increased visceral adiposity".[58][59] The UK's Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition in 2015 disputed the claims of fructose causing metabolic disorders, stating that "there is insufficient evidence to demonstrate that fructose intake, at levels consumed in the normal UK diet, leads to adverse health outcomes independent of any effects related to its presence as a component of total and free sugars."[60]

Cardiometabolic diseases

[edit]When fructose is consumed in excess as a sweetening agent in foods or beverages, it may be associated with increased risk of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disorders that are part of metabolic syndrome.[59]

Compared with sucrose

[edit]Fructose was found to increase triglycerides in type-2 but not type-1 diabetes, and moderate use of it has previously been considered acceptable as a sweetener for diabetics,[61] possibly because it does not trigger the production of insulin by pancreatic β cells.[62] For a 50 gram reference amount, fructose has a glycemic index of 23, compared with 100 for glucose and 60 for sucrose.[63] Fructose is also 73% sweeter than sucrose at room temperature, allowing diabetics to use less of it per serving. Fructose consumed before a meal may reduce the glycemic response of the meal.[64] Fructose-sweetened food and beverage products cause less of a rise in blood glucose levels than do those manufactured with either sucrose or glucose.[58]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Fructose". m-w.com. Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 19 April 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ Levulose comes from the Latin word laevus, "left"; levulose is the old word for the most occurring isomer of fructose. D-fructose rotates plane-polarised light to the left, hence the name."Levulose". Archived from the original on 2009-10-08. Retrieved 2010-01-28..

- ^ "2-Carb-10". Archived from the original on 2023-06-18. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (49th ed.). 1968–69. p. D-186.

- ^ Chambers, Michael. "ChemIDplus – 57-48-7 – BJHIKXHVCXFQLS-UYFOZJQFSA-N – Fructose [USP:JAN] – Similar structures search, synonyms, formulas, resource links, and other chemical information". chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov. US National Institutes of Health. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ a b c Wach, Wolfgang (2004). "Fructose". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a12_047.pub2. ISBN 978-3-527-30385-4.

- ^ Dubrunfaut (1847). "Sur une propriété analytique des fermentations alcoolique et lactique, et sur leur application à l'étude des sucres" [On an analytic property of alcoholic and lactic fermentations, and on their application to the study of sugars]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique (in French). 21: 169–178. Archived from the original on 2014-06-27. On page 174, Dubrunfaut relates the discovery and properties of fructose.

- ^ Fruton, J. S. (1974). "Molecules and Life – Historical Essays on the Interplay of Chemistry and Biology". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 18 (4). New York: Wiley-Interscience. doi:10.1002/food.19740180423. Archived from the original on 2021-02-28. Retrieved 2021-02-05.

- ^ a b Miller, William Allen (1857). "Part III. Organic Chemistry". Elements of Chemistry: Theoretical and Practical. London: John W. Parker and son. pp. 52, 57.

- ^ Hyvonen, L. & Koivistoinen, P (1982). "Fructose in Food Systems". In Birch, G.G. & Parker, K.J (eds.). Nutritive Sweeteners. London & New Jersey: Applied Science Publishers. pp. 133–144. ISBN 978-0-85334-997-6.

- ^ a b "Fructose. Origin and meaning of fructose". Online Etymology Dictionary, Douglas Harper. 2017. Archived from the original on 25 December 2017. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- ^ Shi, Kemeng; Pedersen, Christian Marcus; Guo, Zhaohui; Li, Yanqiu; Zheng, Hongyan; Qiao, Yan; Hu, Tuoping; Wang, Yingxiong (1 December 2018). "NMR studies of the tautomer distributions of d‑fructose in lower alcohols/DMSO‑d6". Journal of Molecular Liquids. 271: 926–932. doi:10.1016/j.molliq.2018.09.067. S2CID 104659783. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Schneider, Bernd; Lichtenthaler, Frieder W.; Steinle, Georg; Schiweck, Hubert (22 December 1985). "Studies on Ketoses, 1 Distribution of Furanoid and Pyranoid Tautomers of D-Fructose in Water, Dimethyl Sulfoxide, and Pyridine via 1H NMR Intensities of Anomeric Hydroxy Groups in [D6]DMSO". Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 1985 (12): 2443–2453. doi:10.1002/jlac.198519851213. Archived from the original on 24 February 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Funcke, Werner; von Sonntag, Clemens; Triantaphylides, Christian (October 1979). "Detection of the open-chain forms of d-fructose and L-sorbose in aqueous solution by using 13C-n.m.r. spectroscopy". Carbohydrate Research. 75: 305–309. doi:10.1016/S0008-6215(00)84649-2. Archived from the original on 28 February 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ McWilliams, Margaret (2001). Foods: Experimental Perspectives, 4th Edition. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-021282-5.

- ^ Keusch, P. "Yeast and Sugar- the Chemistry must be right". Archived from the original on December 20, 2010.

- ^ Dills, WL (1993). "Protein fructosylation: Fructose and the Maillard reaction". Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 58 (5 Suppl): 779–787. doi:10.1093/ajcn/58.5.779S. PMID 8213610.

- ^ Huber, GW; Iborra, S; Corma, A (September 2006). "Synthesis of transportation fuels from biomass: chemistry, catalysts, and engineering". Chem. Rev. 106 (9): 4044–98. doi:10.1021/cr068360d. PMID 16967928.

- ^ a b c d e Hanover, L. M.; White, J. S. (1 November 1993). "Manufacturing, composition, and applications of fructose". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 58 (5): 724S – 732S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/58.5.724S. ISSN 0002-9165. PMID 8213603. Archived from the original on 14 April 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2017 – via nutrition.org.

- ^ "Sugar Sweetness". food.oregonstate.edu. Oregon State University. Archived from the original on May 16, 2008. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ a b c d Lee, Thomas D. (1 January 2000). "Sweeteners". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. doi:10.1002/0471238961.19230505120505.a01.pub2. ISBN 978-0471238966.

- ^ Jana, A.H.; Joshi, N.S.S. (November 1994). "Sweeteners for frozen [desserts] success – a review". Australian Journal of Dairy Technology. 49. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ Shallenberger, R.S. (1994). Taste Chemistry. Chapman and Hall. ISBN 978-0-7514-0150-9.

- ^ a b Nabors, LO (2001). American Sweeteners. pp. 374–375.

- ^ McWilliams, Margaret (2001). Foods: Experimental Perspectives, 4th Edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ : Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-021282-5.

- ^ White, DC; Lauer GN (1990). "Predicting gelatinization temperature of starch/sweetener system for cake formulation by differential scanning calorimetry I. Development of a model". Cereal Foods World. 35: 728–731.

- ^ Margaret M. Wittenberg (2007). New Good Food: Essential Ingredients for Cooking and Eating Well. Diet and Nutrition Series; pages 249–51. Ten Speed Press. p. 249. ISBN 978-1580087506.

fructose traditional baking.

- ^ Park, KY; Yetley AE (1993). "Intakes and food sources of fructose in the United States". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 58 (5 Suppl): 737S – 747S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/58.5.737S. PMID 8213605.

- ^ Riby, JE; Fujisawa T; Kretchmer N (1993). "Fructose absorption". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 58 (5 Suppl): 748S – 753S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/58.5.748S. PMID 8213606.

- ^ a b Kretchmer, N; Hollenbeck CB (1991). Sugars and Sweeteners. CRC Press, Inc.

- ^ a b Use link to FoodData Central (USDA) Archived 2019-10-25 at the Wayback Machine and then search for the particular food, and click on "SR Legacy Foods".

- ^ a b c "High Fructose Corn Syrup: Questions and Answers". US Food and Drug Administration. 5 November 2014. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ White, J. S (2008). "Straight talk about high-fructose corn syrup: What it is and what it ain't". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 88 (6): 1716S – 1721S. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.25825B. PMID 19064536.

- ^ Guthrie, FJ; Morton FJ (2000). "Food sources of added sweeteners in the diets of Americans". Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 100 (1): 43–51. doi:10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00018-3. PMID 10646004.

- ^ "Calories and nutrient composition for fructose, dry powder per 100 g". USDA National Nutrient Database, version SR-28. May 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-02-08.

- ^ "Calories and nutrient composition for sucrose granules per 100 g". USDA National Nutrient Database, version SR-28. May 2016. Archived from the original on 2017-02-08.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ "TABLE 4-7 Comparison of Potassium Adequate Intakes Established in This Report to Potassium Adequate Intakes Established in the 2005 DRI Report". p. 120. In: Stallings, Virginia A.; Harrison, Meghan; Oria, Maria, eds. (2019). "Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. pp. 101–124. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. NCBI NBK545428.

- ^ Stipanuk, Marsha H (2006). Biochemical, Physiological, and Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition, 2nd Edition. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia, PA.

- ^ a b Shi, Ya-Nan; Liu, Ya-Jin; Xie, Zhifang; Zhang, Weiping J. (5 June 2021). "Fructose and metabolic diseases: too much to be good". Chinese Medical Journal. 134 (11): 1276–1285. doi:10.1097/CM9.0000000000001545. PMC 8183764. PMID 34010200.

- ^ a b Fujisawa, T; Riby J; Kretchmer N (1991). "Intestinal absorption of fructose in the rat". Gastroenterology. 101 (2): 360–367. doi:10.1016/0016-5085(91)90012-a. PMID 2065911.

- ^ Ushijima, K; Fujisawa T; Riby J; Kretchmer N (1991). "Absorption of fructose by isolated small intestine of rats is via a specific saturable carrier in the absence of glucose and by the disaccharidase-related transport system in the presence of glucose". Journal of Nutrition. 125 (8): 2156–2164. doi:10.1093/jn/125.8.2156. PMID 7643250.

- ^ Ferraris, R (2001). "Dietary and developmental regulation of intestinal sugar transport". Biochemical Journal. 360 (Pt 2): 265–276. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3600265. PMC 1222226. PMID 11716754.

- ^ a b Beyer, PL; Caviar EM; McCallum RW (2005). "Fructose intake at current levels in the United States may cause gastrointestinal distress in normal adults". J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 105 (10): 1559–1566. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2005.07.002. PMID 16183355.

- ^ Ravich, WJ; Bayless TM; Thomas, M (1983). "Fructose: incomplete intestinal absorption in humans". Gastroenterology. 84 (1): 26–29. doi:10.1016/S0016-5085(83)80162-0. PMID 6847852.

- ^ Riby, JE; Fujisawa T; Kretchmer, N (1993). "Fructose absorption". American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 58 (5 Suppl): 748S – 753S. doi:10.1093/ajcn/58.5.748S. PMID 8213606.

- ^ Rumessen, JJ; Gudman-Hoyer E (1986). "Absorption capacity of fructose in healthy adults. Comparison with sucrose and its constituent monosaccharides". Gut. 27 (10): 1161–1168. doi:10.1136/gut.27.10.1161. PMC 1433856. PMID 3781328.

- ^ Skoog, SM; Bharucha AE (2004). "Dietary fructose and gastrointestinal symptoms: a review". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 99 (10): 2046–50. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40266.x. PMID 15447771. S2CID 12084142.

- ^ Fujisawa, T, T; Mulligan K; Wada L; Schumacher L; Riby J; Kretchmer N (1993). "The effect of exercise on fructose absorption". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 58 (1): 75–9. doi:10.1093/ajcn/58.1.75. PMID 8317393.

- ^ Kawasaki, Takahiro; Akanuma, Hiroshi; Yamanouchi, Toshikazu (2002). "Increased Fructose Concentrations in Blood and Urine in Patients with Diabetes". Diabetes Care. 25 (2): 353–357. doi:10.2337/diacare.25.2.353. PMID 11815509.

- ^ Quezada-Calvillo, R; Robayo CC; Nichols BL (2006). Carbohydrate Digestion and Absorption. Missouri: Saunders, Elsevier. pp. 182–185. ISBN 978-1-4160-0209-3.

- ^ Hajduch, E; Litherland GJ; Turban S; Brot-Laroche E; Hundal HS (Aug 2003). "Insulin regulates the expression of the GLUT5 transporter in L6 skeletal muscle cells". FEBS Letters. 549 (1–3): 77–82. Bibcode:2003FEBSL.549...77H. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(03)00773-7. PMID 12914929. S2CID 25952139.

- ^ MA Parniak; Kalant N (1988). "Enhancement of glycogen concentrations in primary cultures of rat hepatocytes exposed to glucose and fructose". Biochemical Journal. 251 (3): 795–802. doi:10.1042/bj2510795. PMC 1149073. PMID 3415647.

- ^ Jia, Guanghong; Aroor, Annayya R.; Whaley-Connell, Adam T.; Sowers, James R. (June 2014). "Fructose and Uric Acid: Is There a Role in Endothelial Function?". Current Hypertension Reports. 16 (6): 434. doi:10.1007/s11906-014-0434-z. ISSN 1522-6417. PMC 4084511. PMID 24760443.

- ^ Medina Villaamil (2011-02-01). "Fructose transporter Glut5 expression in clear renal cell carcinoma". Oncology Reports. 25 (2): 315–23. doi:10.3892/or.2010.1096. hdl:2183/20620. ISSN 1021-335X. PMID 21165569.

- ^ a b McGrane, MM (2006). Carbohydrate metabolism: Synthesis and oxidation. Missouri: Saunders, Elsevier. pp. 258–277. ISBN 978-1-4160-0209-3.

- ^ a b Sul, HS (2006). Metabolism of Fatty Acids, Acylglycerols, and Sphingolipids. Missouri: Saunders, Elsevier. pp. 450–467. ISBN 978-1-4160-0209-3.

- ^ a b c d "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to fructose and reduction of post-prandial glycaemic responses (ID 558) pursuant to Article 13(1) of Regulation (EC) No 1924/2006". EFSA Journal. 9 (6). EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies: 2223. 2011. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2223.

The Panel notes that these values support a significant decrease in post-prandial blood glucose responses when fructose replaces either sucrose or glucose.

- ^ a b c d EFSA Panel on Nutrition, Novel Foods and Food Allergens (28 February 2022). "Tolerable upper intake level for dietary sugars". EFSA Journal. 20 (2): 337. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2022.7074. hdl:1854/LU-01GWHCPEH24E9RRDYANKYH53MJ. ISSN 1831-4732. PMC 8884083. PMID 35251356. S2CID 247184182. Archived from the original on 26 October 2023. Retrieved 3 October 2022 – via ESFA.

- ^ "Carbohydrates and Health" (PDF). Williams Lea, Norwich, UK: UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition, Public Health England, TSO. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

- ^ Rizkalla, Salwa W (2010). "Health implications of fructose consumption: A review of recent data". Nutrition & Metabolism. 7 (1): 82. doi:10.1186/1743-7075-7-82. ISSN 1743-7075. PMC 2991323. PMID 21050460.

- ^ Thorens, Bernard; Mueckler, Mike (2010). "Glucose transporters in the 21st Century (Review)". American Journal of Physiology. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 298 (2): E141 – E145. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00712.2009. ISSN 0193-1849. PMC 2822486. PMID 20009031.

- ^ "Glycemic index". Glycemic Index Testing and Research, University of Sydney (Australia) Glycemic Index Research Service (SUGiRS). 2 May 2017. Archived from the original on 16 January 2021. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- ^ Patricia M. Heacock; Steven R. Hertzler; Bryan W. Wolf (2002). "Fructose Prefeeding Reduces the Glycemic Response to a High-Glycemic Index, Starchy Food in Humans". Journal of Nutrition. 132 (9): 2601–2604. doi:10.1093/jn/132.9.2601. PMID 12221216.

External links

[edit] Media related to Fructose at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fructose at Wikimedia Commons

Fructose

View on GrokipediaEtymology and History

Etymology

The term "fructose" is derived from the Latin word fructus, meaning "fruit," reflecting the sugar's initial isolation from fruit sources, and combined with the chemical suffix -ose, which indicates a carbohydrate sugar.[4] This naming convention emerged during the 19th-century advancements in carbohydrate chemistry, when scientists systematically identified and labeled individual sugars.[5] The name "fructose" was coined in 1857 by English chemist William Allen Miller.[6] Like other monosaccharides, it follows patterns seen in glucose—derived from the Greek glykys ("sweet") with the -ose suffix—and sucrose, from French sucre ("sugar") plus -ose.[7]Discovery and Early Research

In the late 18th century, Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele conducted pioneering experiments on the chemical constituents of fruits and berries, analyzing over twenty varieties to identify organic acids present in them. His work laid foundational insights into the composition of fruit constituents, though he did not fully isolate individual monosaccharides.[8] Building on such early investigations, French chemist Joseph-Louis Proust advanced the understanding of fruit sugars in 1808 by identifying two distinct types—glucose and sucrose—in various plant juices through systematic extraction and analysis. Proust's observations highlighted the differences in their properties, marking a key step in distinguishing fruit-derived sugars from cane sugar.[9] A significant breakthrough occurred in 1847 when French chemist Augustin-Pierre Dubrunfaut isolated fructose from the hydrolysis of cane sugar, producing invert sugar—a mixture from which he separated one component as an insoluble calcium salt. This process demonstrated fructose's presence alongside glucose in the hydrolysate, confirming its role in sucrose breakdown.[10][5] Further clarification came in 1857 when the distinction between fructose and glucose was refined through comparative studies of their optical properties, leading to fructose's alternative naming as levulose due to its levorotatory effect on polarized light, in contrast to the dextrorotatory glucose. This naming convention, rooted in the sugar's fruit origins (from Latin fructus), underscored its unique identity.[11][5]Chemical Structure and Properties

Molecular Structure and Isomers

Fructose is a monosaccharide with the molecular formula , classified as a ketohexose due to its six-carbon chain and ketone functional group at the second carbon atom.[12] In its open-chain representation, the structure features a carbonyl group (C=O) at C2, flanked by hydroxyl groups on the remaining carbons, which defines its ketose nature distinct from aldoses like glucose.[13] This linear form, while useful for structural depiction, is not predominant in solution; instead, fructose undergoes spontaneous ring-chain tautomerism to form cyclic hemiacetals.[14] The cyclic forms of fructose include both furanose and pyranose rings, arising from intramolecular nucleophilic attack by a hydroxyl group on the ketone carbon at C2. The furanose form creates a five-membered ring when the C5 hydroxyl attacks C2, resulting in a structure with the anomeric hydroxyl at C2 and a side chain from C6; this form constitutes about 23% β-fructofuranose in aqueous equilibrium.[15] The pyranose form, more stable, involves the C6 hydroxyl attacking C2 to form a six-membered ring, comprising roughly 70% β-fructopyranose, with minor α-anomers and less than 1% open-chain species.[15] These cyclic configurations introduce a new chiral center at the anomeric carbon (C2), leading to α and β anomers that interconvert via mutarotation, involving pyranose-furanose equilibria.[12] Fructose exists primarily as the D-enantiomer in nature, determined by the configuration at C5 in its Fischer projection, which aligns with the D-series of sugars.[16] The mirror-image L-fructose is exceedingly rare, occurring only in trace amounts or synthetically, as biological systems favor D-forms for metabolic compatibility.[17] Optically, D-fructose exhibits a specific rotation of , reflecting its levorotatory property in polarimetry measurements.[13] Beyond ring formation, fructose demonstrates keto-enol tautomerism, enabling isomerization to aldoses such as glucose through a common enediol intermediate, a process catalyzed enzymatically in pathways like glycolysis.[18] This tautomerism underscores the structural flexibility of fructose, allowing interconversion between ketose and aldose configurations under appropriate conditions.[19]Chemical Reactions

Fructose undergoes base- or acid-catalyzed isomerization to glucose and mannose through the Lobry de Bruyn–van Ekenstein transformation, which proceeds via a common enediol intermediate formed by enolization of the keto group at C2.[20] This equilibrium reaction, first described in the late 19th century, favors fructose under alkaline conditions but allows reversible conversion among the three hexoses, with the keto functionality of fructose enhancing its reactivity compared to aldoses.[21] In the Maillard reaction, fructose reacts non-enzymatically with the amino groups of amino acids or proteins under heating, initiating a complex series of condensations, rearrangements, and fragmentations that ultimately form advanced glycation end-products, including brown pigments known as melanoidins.[22] Fructose's ketose structure promotes faster initial Amadori rearrangement to fructosyl-amino acids than glucose, leading to more rapid melanoidin formation and contributing to flavor and color development in processed foods.[23] Under acidic conditions, fructose readily dehydrates to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), a key platform chemical, through sequential elimination of three water molecules from its furanose form, typically catalyzed by mineral acids like sulfuric acid at elevated temperatures.[24] This reaction achieves high selectivity (up to 95%) in biphasic solvent systems, with HMF serving as a precursor for biofuels and polymers, though side reactions like polymerization can occur at prolonged heating.[25] Yeast, particularly Saccharomyces cerevisiae, ferments fructose anaerobically to ethanol and carbon dioxide via glycolysis, where fructose is first phosphorylated to fructose-6-phosphate and then metabolized identically to glucose-derived intermediates, yielding 2 moles of ethanol and 2 moles of CO2 per mole of fructose.[26] This process is central to alcoholic beverage production, with fructose often co-fermented alongside glucose in fruit musts, though fructose utilization can lag slightly due to transport preferences.[27] Chemical reduction of fructose, typically via catalytic hydrogenation with Raney nickel or ruthenium catalysts under hydrogen pressure, converts the carbonyl group to an alcohol, yielding sorbitol as the primary product alongside minor mannitol from epimerization.[28] Conversely, catalytic oxidation of fructose with molecular oxygen over platinum or gold catalysts produces gluconic acid derivatives such as 2-keto-D-gluconic acid and D-threo-hex-2,5-hexodiulose, involving selective attack at the C1 and C6 hydroxyls or the C2 keto group.[29] These transformations highlight fructose's versatility in industrial synthesis of sugar alcohols and acids for food and pharmaceutical applications.Physical and Functional Properties

Solubility, Sweetness, and Crystallization

Fructose is highly soluble in water, dissolving at a rate of approximately 375 g per 100 mL at 20°C, surpassing the solubility of sucrose, which is around 200 g per 100 mL under the same conditions.[30] This elevated solubility arises from fructose's molecular structure, facilitating strong hydrogen bonding with water molecules. Compared to glucose, whose solubility is about 91 g per 100 mL at 20°C, fructose's solubility curve shows a steeper increase with temperature, reaching over 500 g per 100 mL at 50°C, while glucose and sucrose exhibit more moderate rises. In terms of sweetness, fructose is perceived as 1.2 to 1.8 times sweeter than sucrose, with optimal sweetness at concentrations of 3–10% in solution.[31] This enhanced relative sweetness stems from fructose's stronger binding affinity to the human sweet taste receptor heterodimer T1R2/T1R3, particularly at the Venus flytrap domain of T1R2, where it elicits a more potent activation than sucrose.[32] The perception varies with temperature and concentration, peaking relative to sucrose at lower levels and cooler temperatures. Fructose primarily crystallizes as the monohydrate form, β-D-fructopyranose·H₂O, which is stable under ambient conditions and exhibits a melting point around 80–85°C with partial dehydration.[33] The anhydrous form can be obtained by heating above 90°C or through controlled dehydration processes, melting at 103°C before decomposition. Crystallization of fructose poses challenges due to its low melting point and high solubility, often requiring seeding and cooling under vacuum to avoid viscous syrup formation or premature melting during the process.[34] Its hygroscopic nature can influence storage by promoting deliquescence in humid environments, complicating anhydrous form handling.[35]Hygroscopicity, Freezing Point, and Food Applications

Fructose is highly hygroscopic, readily absorbing moisture from the atmosphere, which positions it as an effective humectant in various food formulations. This property enables fructose to bind water molecules tightly, preventing the drying out of products such as baked goods and confections, thereby extending shelf life and maintaining desirable textures.[36] In baked goods specifically, fructose's humectancy promotes prolonged softness by retaining moisture within the matrix, reducing staling rates compared to less hygroscopic sweeteners like sucrose.[37] The freezing point of aqueous fructose solutions is notably depressed, with approximately 1.2°C reduction per 10% concentration by weight, owing to its lower molecular weight relative to disaccharides like sucrose, which achieves only about half that effect. This colligative property enhances the functionality of fructose in frozen foods, such as ice creams and sorbets, by lowering the initial freezing temperature and promoting smaller ice crystal formation for improved creaminess and scoopability.[38] In food processing, fructose contributes to starch gelatinization by elevating the gelatinization temperature and enthalpy, which can result in higher degrees of starch swelling and firmer textures in baked items when substituted for sucrose. Additionally, fructose exhibits inhibitory effects on enzymatic browning in processed fruits by competing with substrates for polyphenol oxidase activity, helping to preserve visual appeal without extensive additives. Its application in low-calorie foods leverages this alongside its intense sweetness (about 1.7 times that of sucrose), allowing reduced usage for calorie control while enhancing texture in confections through moisture retention and smooth mouthfeel.[39][40][41]Natural and Commercial Sources

Occurrence in Foods

Fructose is a monosaccharide naturally abundant in many plant-based foods, serving as a key energy source in fruits, vegetables, and certain sweeteners. It occurs primarily as free fructose or as a component of disaccharides like sucrose, which breaks down into equal parts glucose and fructose. In fruits, fructose levels are typically higher than in other food groups, contributing to their sweetness and palatability. For instance, apples and pears contain 5–10% fructose by weight, varying by cultivar and ripeness. Honey represents one of the richest natural sources of fructose, with concentrations ranging from 38% to 40% of its total composition, derived from nectar processed by bees. In contrast, vegetables generally have lower fructose content, often below 2%, and it is notably absent in most grains, which primarily store energy as starch. Sucrose, which contains 50% fructose, is prevalent in sugarcane (up to 15–20% of fresh weight) and sugar beets (around 15–20% of fresh weight), making these crops significant indirect sources of dietary fructose. Fructose content in foods can fluctuate due to seasonal factors, such as sunlight exposure and harvest timing, as well as varietal differences within species; for example, sweeter apple varieties like Fuji may exceed 8% fructose compared to tart Granny Smith types at around 5%. These variations influence the overall sweetness and nutritional profile of fresh produce. The following table summarizes approximate fructose concentrations (as a percentage of total weight) in selected common foods, based on data from nutritional databases and analytical studies:| Food Category | Example | Fructose Content (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Fruits | Apple | 5.9 |

| Fruits | Pear | 6.2 |

| Fruits | Banana | 4.9 |

| Fruits | Grape | 8.1 |

| Fruits | Orange | 2.3 |

| Vegetables | Onion | 1.1 |

| Vegetables | Tomato | 1.2 |

| Vegetables | Carrot | 0.6 |

| Sweeteners | Honey | 38–40 |

| Sweeteners | HFCS-55 | 55 |

| Sucrose Sources | Sugarcane (sucrose) | 7.5–10 (as fructose component) |

| Sucrose Sources | Sugar Beet (sucrose) | 7.5 (as fructose component) |

Industrial Production and Sweeteners

The industrial production of fructose primarily relies on corn starch as a feedstock, marking a significant shift in the sweetener industry during the 1970s when escalating global sugar prices—driven by shortages and trade restrictions—prompted a transition from cane and beet sugar to more affordable corn-derived alternatives, facilitated by U.S. corn subsidies.[42][43] This change was accelerated by advancements in enzyme technology, enabling large-scale production of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) as a direct substitute for sucrose in food and beverage applications.[44] The core process begins with the enzymatic hydrolysis of corn starch into glucose syrup using alpha-amylase and glucoamylase enzymes, followed by the reversible isomerization of glucose to fructose catalyzed by immobilized glucose isomerase, a metalloenzyme derived from bacteria such as Streptomyces species.[45][46] This step typically yields HFCS-42, containing approximately 42% fructose and 50-52% glucose on a dry basis, with the remainder consisting of oligosaccharides and water.[47] To achieve higher fructose concentrations, such as in HFCS-55 (55% fructose and 41% glucose), the initial syrup undergoes chromatographic separation using simulated moving bed technology with cation-exchange resins, which exploits differences in molecular affinity to isolate a high-purity fructose stream (>90% fructose) that is then blended back with glucose syrup.[48][49] For crystalline fructose, an even purer product (typically 99.5% fructose), the separated fructose stream is further refined through evaporation, cooling, and crystallization, meeting food-grade standards set by regulatory bodies like the FDA.[47][50] Commercial fructose sweeteners are standardized by purity and fructose content to ensure consistency in sweetness and functionality; HFCS-42 is widely used in processed foods and baking due to its lower cost and balanced viscosity, while HFCS-55 is preferred for beverages like soft drinks for its sucrose-like sweetness profile.[47][44] Crystalline fructose, with its high purity, serves niche applications in dry mixes and pharmaceuticals, offering superior solubility and reduced hygroscopicity compared to liquid forms.[50] Global production of HFCS and related fructose products reached approximately 11.8 million metric tons in 2023, predominantly in the United States, China, and Mexico, with projections indicating steady growth at a compound annual rate of 3-5% through 2030, driven by demand in the expanding food and beverage sector.[51][52] This scale underscores the efficiency of enzymatic and chromatographic methods, which have made corn-based fructose a cornerstone of modern sweetener manufacturing.[45]Digestion and Absorption

Human Absorption Mechanisms

Fructose absorption in humans occurs primarily in the jejunum of the small intestine via a passive, carrier-mediated diffusion process. The key transporter is GLUT5 (SLC2A5), a facilitative hexose transporter embedded in the apical brush-border membrane of enterocytes, which exhibits high specificity for fructose with a Michaelis constant (Km) of approximately 6 mM. Once inside the enterocyte, fructose diffuses across the basolateral membrane through GLUT2 (SLC2A2), another facilitative transporter with lower affinity for fructose (Km > 30 mM), entering the portal circulation. This mechanism ensures efficient uptake under physiological conditions, where luminal fructose concentrations are typically low.[53][54] In contrast to glucose absorption, which relies on the active, sodium-dependent SGLT1 transporter for apical entry, fructose uptake via GLUT5 is energy-independent and driven by concentration gradients. This passive nature limits fructose absorption to the transporter's saturation point, without the electrochemical coupling that enables near-complete glucose absorption even at high loads. GLUT5 expression is upregulated by dietary fructose through transcriptional mechanisms and endosomal trafficking, enhancing capacity over time with chronic exposure.[53][54][55] When fructose is co-ingested with glucose, as in sucrose or high-fructose corn syrup, absorption efficiency increases due to glucose-induced translocation of GLUT2 from intracellular stores to the apical membrane, forming a transient absorptive complex that facilitates fructose entry. The human small intestine's capacity for fructose absorption is saturable, with healthy adults typically handling 25–50 g per day without malabsorption; single bolus rates approach 25 g per hour before overload. Absorbed fructose is then conveyed directly to the liver via the portal vein for first-pass metabolism. At higher doses exceeding this threshold, such as 50 g or more, partial malabsorption can occur.[54][56][53]Fructose Malabsorption

Fructose malabsorption is a common gastrointestinal disorder characterized by impaired uptake of fructose in the small intestine due to limited capacity of the fructose transporter GLUT5, leading to incomplete absorption even in healthy individuals when fructose intake exceeds approximately 25 grams.[57] Studies indicate that incomplete fructose absorption occurs in 10-60% of the population, depending on the dose tested, with higher rates observed at loads of 50 grams, affecting up to 58% of subjects in some cohorts.[57] This condition is distinct from rare hereditary forms and is often acquired, influenced by factors such as age, concurrent glucose intake, and intestinal health.[58] The primary symptoms of fructose malabsorption include bloating, abdominal pain, flatulence, and diarrhea, which arise from two main mechanisms: osmotic effects and bacterial fermentation. Unabsorbed fructose in the intestinal lumen exerts an osmotic pull, drawing water into the gut and causing diarrhea, while colonic bacteria ferment the excess sugar, producing gases such as hydrogen, carbon dioxide, and methane, which lead to bloating and discomfort.[57] These symptoms typically manifest 30-120 minutes after fructose consumption and can mimic irritable bowel syndrome, particularly in sensitive individuals.[58] In contrast to the normal absorption capacity that handles up to 25 grams without issue in most people, those with malabsorption experience symptoms at lower thresholds, often below 15 grams.[57] Diagnosis of fructose malabsorption is primarily achieved through the hydrogen breath test (HBT), in which patients ingest 25 grams of fructose dissolved in water, and breath samples are analyzed for elevated hydrogen levels (>20 parts per million above baseline) indicating malabsorption due to fermentation.[57] This threshold of 25 grams is considered the standard diagnostic load for adults, as it reflects typical dietary amounts and distinguishes malabsorption from normal variation, with positive results in about 11-40% of tested individuals depending on the population.[58] Confirmation may involve ruling out small intestinal bacterial overgrowth via a prior glucose breath test to ensure accuracy.[59] Management focuses on dietary interventions, with the low-FODMAP diet being the most effective approach, as it restricts fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols, including excess free fructose, thereby reducing symptom severity in up to 75% of affected patients.[58] Individuals with fructose malabsorption often seek to avoid high-fructose foods to prevent symptoms such as bloating and diarrhea; this includes focusing on foods where fructose exceeds glucose or those high in fructans, such as apples, pears, onions, and wheat products. Co-ingestion of glucose with fructose can enhance absorption by facilitating GLUT2-mediated transport, alleviating symptoms during moderate intake.[57][60][61] In rare cases of essential fructose malabsorption, genetic mutations in the SLC2A5 gene, which encodes the GLUT5 transporter, impair fructose uptake from infancy, leading to severe symptoms that require lifelong strict avoidance; however, such mutations do not contribute to the more common acquired form.[62]Metabolism

Fructolysis and Key Pathways

Fructolysis refers to the metabolic breakdown of fructose, which occurs primarily in the liver following its absorption from the diet and delivery via the portal vein.[1] In humans, approximately 90% of an oral fructose load undergoes first-pass extraction in the liver, with minor metabolism also taking place in the kidney and small intestine.[63][1] The process begins with the phosphorylation of fructose by the enzyme fructokinase (also known as ketohexokinase), which converts fructose and ATP into fructose-1-phosphate (F1P) and ADP. This reaction is represented as: Fructokinase is highly active in the liver and operates without insulin regulation, allowing rapid fructose processing that bypasses the phosphofructokinase-1 step in glycolysis.[1][64] Subsequently, F1P is cleaved by aldolase B (fructose-1-phosphate aldolase) into dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and glyceraldehyde.[1] DHAP directly enters the glycolytic pathway, while glyceraldehyde is phosphorylated by triokinase to form glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (G3P), enabling both triose phosphates to feed into glycolysis at the triose phosphate level for further conversion to pyruvate or other intermediates.[1][64] This entry point distinguishes fructolysis from glucose metabolism, as it avoids upstream regulatory steps and facilitates unregulated flux through glycolytic and lipogenic pathways in the liver.[1]Biosynthesis and Regulation

In plants, fructose is biosynthesized primarily through the Calvin-Benson cycle in photosynthetic tissues, where triose phosphates generated from CO₂ fixation are converted into fructose-6-phosphate via enzymes such as aldolase and fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase.[65] This fructose-6-phosphate is then utilized in the cytosol for sucrose synthesis by combining with UDP-glucose through sucrose phosphate synthase and sucrose phosphate phosphatase.[66] In sink tissues like developing fruits and seeds, sucrose is transported from source leaves and hydrolyzed by invertase enzymes, yielding equimolar amounts of fructose and glucose to support growth and storage.[67] In mammals, fructose synthesis occurs endogenously via the polyol pathway, a two-step process where glucose is first reduced to sorbitol by aldose reductase using NADPH, followed by oxidation of sorbitol to fructose by sorbitol dehydrogenase utilizing NAD⁺.[68] This pathway operates in various tissues, including the liver, kidney, and adipose tissue, and becomes prominent under hyperglycemic conditions to manage excess glucose.[69] In adipose tissue specifically, the polyol pathway contributes to local fructose production, which can influence lipid metabolism.[70] The regulation of fructose biosynthesis via the polyol pathway is modulated by systemic hormones that control glucose homeostasis. Insulin suppresses the pathway indirectly by promoting glucose uptake and utilization in peripheral tissues, thereby reducing substrate availability for aldose reductase in adipose tissue.[71] Conversely, glucagon elevates blood glucose levels by stimulating hepatic glycogenolysis, enhancing flux through the polyol pathway in adipose and other tissues during fasting or stress states.[72] Fructose plays a key regulatory role in plant developmental processes, particularly seed germination and fruit ripening. During seed germination in species like Arabidopsis, fructose acts as a signaling molecule that interacts with hormones such as abscisic acid and gibberellins to modulate seedling establishment, often inhibiting premature growth under stress conditions.[73] In fruit ripening, fructose accumulates as sucrose imported from leaves is cleaved by invertases and sucrose synthases, contributing to osmotic adjustments, sink strength, and metabolic shifts that drive climacteric ethylene production and softening in fruits like grapes and tomatoes.[74] Microbial production of fructose has been advanced through recombinant engineering of Escherichia coli to express glucose isomerase, enabling efficient isomerization of glucose to fructose for applications like high-fructose corn syrup. Engineered strains co-expressing thermostable glucose isomerase variants achieve high conversion yields, with immobilization techniques enhancing stability and productivity in industrial bioprocesses.[75]Health Implications

Metabolic Effects and Diseases

Fructose is rapidly metabolized in the liver, where over 90% undergoes first-pass metabolism, leading to efficient conversion into lipids through de novo lipogenesis (DNL). This process is enhanced by fructose's ability to upregulate key enzymes such as acetyl-CoA carboxylase and fatty acid synthase via the transcription factor SREBP-1c, bypassing insulin regulation and promoting triglyceride accumulation even in the presence of insulin resistance. In human studies, DNL accounts for approximately 23% of hepatic triglycerides in individuals with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), compared to 10% in those with low liver fat, underscoring fructose's preferential role over high-fat diets in driving hepatic steatosis.[76] Excessive fructose intake is strongly associated with NAFLD, characterized by hepatic fat accumulation independent of alcohol consumption. Fructose promotes NAFLD through activation of lipogenesis, suppression of fatty acid oxidation, and induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress, with animal models demonstrating clear causation and human epidemiological data showing dose-dependent increases in liver fat. Similarly, fructose contributes to insulin resistance by elevating intrahepatic lipids and impairing hepatic insulin sensitivity, a process exacerbated in conditions of obesity where DNL is already heightened. However, epidemiological evidence indicates that fructose from whole fruits and vegetables does not increase risks of metabolic diseases, likely owing to the protective effects of fiber and micronutrients. Fructose occurs naturally in fruits, vegetables, and honey, and when consumed as part of whole foods, it does not pose the same risks as added fructose in the form of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) found in processed foods and beverages. Many individuals seek to reduce intake of added sugars, including HFCS, to lower risks of metabolic diseases such as obesity, NAFLD, and cardiovascular disease.[77][78][76] Regarding gout, fructose metabolism depletes hepatic ATP, activating AMP deaminase and purine degradation pathways that elevate serum uric acid levels by 1-2 mg/dL acutely, increasing hyperuricemia risk; meta-analyses of over 125,000 participants confirm higher fructose consumption correlates with elevated gout incidence.[79][76][80][81] Studies from the 2020s have linked high fructose intake exceeding 50 g/day—common in Western diets through sugar-sweetened beverages—to increased cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. For instance, prospective cohort analyses indicate that intakes above this threshold are associated with a 10-20% higher hazard ratio for CVD events, mediated by dyslipidemia, endothelial dysfunction, and uric acid elevation, with one meta-analysis reporting a 10% risk increase per additional 250 mL of fructose-containing beverages daily.[82][83] Excess fructose also alters the gut microbiome, inducing dysbiosis characterized by reduced microbial diversity and shifts toward pro-inflammatory taxa. High-fructose diets increase intestinal permeability, allowing bacterial endotoxins to enter circulation and exacerbate hepatic inflammation, while decreasing short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria; recent reviews highlight this as a key mechanism linking fructose to metabolic syndrome, with fiber-adapted microbiomes showing potential to mitigate these effects by enhancing fructose clearance in the small intestine.[84][85] Hereditary fructose intolerance (HFI) is a rare genetic disorder caused by a deficiency in the enzyme aldolase B, resulting in the accumulation of fructose-1-phosphate in the liver and kidneys. This condition can lead to severe symptoms such as hypoglycemia, vomiting, abdominal pain, jaundice, and potential liver and kidney damage or failure if fructose is ingested, necessitating strict lifelong avoidance of fructose, sucrose, and sorbitol-containing foods. Natural sources of fructose include all fruits and some vegetables, while added sources encompass high-fructose corn syrup in processed foods, honey, agave nectar, and sugary drinks.[86] Fructose metabolism exhibits notable differences between pediatric and adult populations, with children displaying greater variability in absorption—ranging from 30-90% efficiency due to immature intestinal transporters—and heightened susceptibility to adverse effects like hepatic lipid accumulation at lower relative doses. In contrast, adults often experience more consistent but still elevated risks tied to cumulative exposure, though pediatric studies report stronger associations with early-onset insulin resistance and NAFLD progression owing to developing regulatory pathways.[87][88]Comparisons with Other Sugars

Fructose exhibits distinct physical and metabolic properties when compared to other common sugars such as glucose and sucrose. In terms of sweetness, fructose is approximately 1.2 to 1.8 times sweeter than sucrose on a molar basis, and significantly sweeter than glucose, which allows for lower quantities to achieve equivalent perceived sweetness in food applications.[89] This heightened sweetness contributes to its widespread use in sweeteners, though it does not directly influence metabolic outcomes. Regarding glycemic impact, fructose has a low glycemic index (GI) of 19, in contrast to glucose's GI of 100 and sucrose's GI of 65, meaning it causes minimal elevation in blood glucose levels due to its primary hepatic metabolism bypassing systemic glucose regulation.[90]| Sugar | Relative Sweetness (vs. Sucrose = 1) | Glycemic Index |

|---|---|---|

| Fructose | 1.2–1.8 | 19 |

| Glucose | 0.7–0.8 | 100 |

| Sucrose | 1.0 | 65 |