Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Incircle and excircles

View on Wikipedia

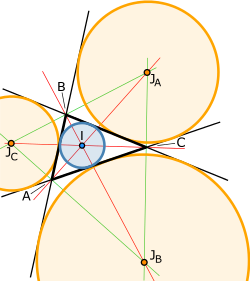

In geometry, the incircle or inscribed circle of a triangle is the largest circle that can be contained in the triangle; it touches (is tangent to) the three sides. The center of the incircle is a triangle center called the triangle's incenter.[1]

An excircle or escribed circle[2] of the triangle is a circle lying outside the triangle, tangent to one of its sides and tangent to the extensions of the other two. Every triangle has three distinct excircles, each tangent to one of the triangle's sides.[3]

The center of the incircle, called the incenter, can be found as the intersection of the three internal angle bisectors.[3][4] The center of an excircle is the intersection of the internal bisector of one angle (at vertex A, for example) and the external bisectors of the other two. The center of this excircle is called the excenter relative to the vertex A, or the excenter of A.[3] Because the internal bisector of an angle is perpendicular to its external bisector, it follows that the center of the incircle together with the three excircle centers form an orthocentric system.[5]

Incircle and Incenter

[edit]Suppose has an incircle with radius and center . Let be the length of , the length of , and the length of .

Also let , , and be the touchpoints where the incircle touches , , and .

Incenter

[edit]The incenter is the point where the internal angle bisectors of meet.

Trilinear coordinates

[edit]The trilinear coordinates for a point in the triangle is the ratio of all the distances to the triangle sides. Because the incenter is the same distance from all sides of the triangle, the trilinear coordinates for the incenter are[6]

Barycentric coordinates

[edit]The barycentric coordinates for a point in a triangle give weights such that the point is the weighted average of the triangle vertex positions. Barycentric coordinates for the incenter are given by

where , , and are the lengths of the sides of the triangle, or equivalently (using the law of sines) by

where , , and are the angles at the three vertices.

Cartesian coordinates

[edit]The Cartesian coordinates of the incenter are a weighted average of the coordinates of the three vertices using the side lengths of the triangle relative to the perimeter (that is, using the barycentric coordinates given above, normalized to sum to unity) as weights. The weights are positive so the incenter lies inside the triangle as stated above. If the three vertices are located at , , and , and the sides opposite these vertices have corresponding lengths , , and , then the incenter is at[citation needed]

Radius

[edit]The inradius of the incircle in a triangle with sides of length , , is given by[7]

where is the semiperimeter (see Heron's formula).

The tangency points of the incircle divide the sides into segments of lengths from , from , and from (see Tangent lines to a circle).[8]

Distances to the vertices

[edit]Denote the incenter of as .

The distance from vertex to the incenter is:

Derivation of the formula stated above

[edit]Use the Law of sines in the triangle .

We get . We have that .

It follows that .

The equality with the second expression is obtained the same way.

The distances from the incenter to the vertices combined with the lengths of the triangle sides obey the equation[9]

Additionally,[10]

where and are the triangle's circumradius and inradius respectively.

Other properties

[edit]The collection of triangle centers may be given the structure of a group under coordinate-wise multiplication of trilinear coordinates; in this group, the incenter forms the identity element.[6]

Incircle and its radius properties

[edit]Distances between vertex and nearest touchpoints

[edit]The distances from a vertex to the two nearest touchpoints are equal; for example:[11]

Other properties

[edit]If the altitudes from sides of lengths , , and are , , and , then the inradius is one third the harmonic mean of these altitudes; that is,[12]

The product of the incircle radius and the circumcircle radius of a triangle with sides , , and is[13]

Some relations among the sides, incircle radius, and circumcircle radius are:[14]

Any line through a triangle that splits both the triangle's area and its perimeter in half goes through the triangle's incenter (the center of its incircle). There are either one, two, or three of these for any given triangle.[15]

The incircle radius is no greater than one-ninth the sum of the altitudes.[16]: 289

The squared distance from the incenter to the circumcenter is given by[17]: 232

and the distance from the incenter to the center of the nine point circle is[17]: 232

The incenter lies in the medial triangle (whose vertices are the midpoints of the sides).[17]: 233, Lemma 1

Relation to area of the triangle

[edit]The radius of the incircle is related to the area of the triangle.[18] The ratio of the area of the incircle to the area of the triangle is less than or equal to , with equality holding only for equilateral triangles.[19]

Suppose has an incircle with radius and center . Let be the length of , the length of , and the length of .

Now, the incircle is tangent to at some point , and so is right. Thus, the radius is an altitude of .

Therefore, has base length and height , and so has area .

Similarly, has area and has area .

Since these three triangles decompose , we see that the area is:

and

where is the area of and is its semiperimeter.

For an alternative formula, consider . This is a right-angled triangle with one side equal to and the other side equal to . The same is true for . The large triangle is composed of six such triangles and the total area is:[citation needed]

Gergonne triangle and point

[edit]

The Gergonne triangle (of ) is defined by the three touchpoints of the incircle on the three sides. The touchpoint opposite is denoted , etc.

This Gergonne triangle, , is also known as the contact triangle or intouch triangle of . Its area is

where , , and are the area, radius of the incircle, and semiperimeter of the original triangle, and , , and are the side lengths of the original triangle. This is the same area as that of the extouch triangle.[20]

The three lines , , and intersect in a single point called the Gergonne point, denoted as (or triangle center X7). The Gergonne point lies in the open orthocentroidal disk punctured at its own center, and can be any point therein.[21]

The Gergonne point of a triangle has a number of properties, including that it is the symmedian point of the Gergonne triangle.[22]

Trilinear coordinates for the vertices of the intouch triangle are given by[citation needed]

Trilinear coordinates for the Gergonne point are given by[citation needed]

or, equivalently, by the Law of Sines,

Excircles and excenters

[edit]

An excircle or escribed circle[2] of the triangle is a circle lying outside the triangle, tangent to one of its sides, and tangent to the extensions of the other two. Every triangle has three distinct excircles, each tangent to one of the triangle's sides.[3]

The center of an excircle is the intersection of the internal bisector of one angle (at vertex , for example) and the external bisectors of the other two. The center of this excircle is called the excenter relative to the vertex , or the excenter of .[3] Because the internal bisector of an angle is perpendicular to its external bisector, it follows that the center of the incircle together with the three excircle centers form an orthocentric system.[5]

Trilinear coordinates of excenters

[edit]While the incenter of has trilinear coordinates , the excenters have trilinears[citation needed]

Exradii

[edit]The radii of the excircles are called the exradii.

The exradius of the excircle opposite (so touching , centered at ) is[23][24]

- where

See Heron's formula.

Derivation of exradii formula

[edit]Source:[23]

Let the excircle at side touch at side extended at , and let this excircle's radius be and its center be . Then is an altitude of , so has area . By a similar argument, has area and has area . Thus the area of triangle is

- .

So, by symmetry, denoting as the radius of the incircle,

- .

By the Law of Cosines, we have

Combining this with the identity , we have

But , and so

which is Heron's formula.

Combining this with , we have

Similarly, gives

Other properties

[edit]From the formulas above one can see that the excircles are always larger than the incircle and that the largest excircle is the one tangent to the longest side and the smallest excircle is tangent to the shortest side. Further, combining these formulas yields:[25]

Other excircle properties

[edit]The circular hull of the excircles is internally tangent to each of the excircles and is thus an Apollonius circle.[26] The radius of this Apollonius circle is where is the incircle radius and is the semiperimeter of the triangle.[27]

The following relations hold among the inradius , the circumradius , the semiperimeter , and the excircle radii , , :[14]

The circle through the centers of the three excircles has radius .[14]

If is the orthocenter of , then[14]

Nagel triangle and Nagel point

[edit]

The Nagel triangle or extouch triangle of is denoted by the vertices , , and that are the three points where the excircles touch the reference and where is opposite of , etc. This is also known as the extouch triangle of . The circumcircle of the extouch is called the Mandart circle (cf. Mandart inellipse).

The three line segments , and are called the splitters of the triangle; they each bisect the perimeter of the triangle,[citation needed]

The splitters intersect in a single point, the triangle's Nagel point (or triangle center X8).

Trilinear coordinates for the vertices of the extouch triangle are given by[citation needed]

Trilinear coordinates for the Nagel point are given by[citation needed]

or, equivalently, by the Law of Sines,

The Nagel point is the isotomic conjugate of the Gergonne point.[citation needed]

Related constructions

[edit]Nine-point circle and Feuerbach point

[edit]

In geometry, the nine-point circle is a circle that can be constructed for any given triangle. It is so named because it passes through nine significant concyclic points defined from the triangle. These nine points are:[28][29]

- The midpoint of each side of the triangle

- The foot of each altitude

- The midpoint of the line segment from each vertex of the triangle to the orthocenter (where the three altitudes meet; these line segments lie on their respective altitudes).

In 1822, Karl Feuerbach discovered that any triangle's nine-point circle is externally tangent to that triangle's three excircles and internally tangent to its incircle; this result is known as Feuerbach's theorem. He proved that:[30]

- ... the circle which passes through the feet of the altitudes of a triangle is tangent to all four circles which in turn are tangent to the three sides of the triangle ... (Feuerbach 1822)

The triangle center at which the incircle and the nine-point circle touch is called the Feuerbach point.

The incircle may be described as the pedal circle of the incenter. The locus of points whose pedal circles are tangent to the nine-point circle is known as the McCay cubic.

Incentral and excentral triangles

[edit]The points of intersection of the interior angle bisectors of with the segments , , and are the vertices of the incentral triangle. Trilinear coordinates for the vertices of the incentral triangle are given by[citation needed]

The excentral triangle of a reference triangle has vertices at the centers of the reference triangle's excircles. Its sides are on the external angle bisectors of the reference triangle (see figure at top of page). Trilinear coordinates for the vertices of the excentral triangle are given by[citation needed]

Equations for four circles

[edit]Let be a variable point in trilinear coordinates, and let , , . The four circles described above are given equivalently by either of the two given equations:[31]: 210–215

- Incircle:

- -excircle:

- -excircle:

- -excircle:

Euler's theorem

[edit]Euler's theorem states that in a triangle:

where and are the circumradius and inradius respectively, and is the distance between the circumcenter and the incenter.

For excircles the equation is similar:

where is the radius of one of the excircles, and is the distance between the circumcenter and that excircle's center.[32][33][34]

Generalization to other polygons

[edit]Some (but not all) quadrilaterals have an incircle. These are called tangential quadrilaterals. Among their many properties perhaps the most important is that their two pairs of opposite sides have equal sums. This is called the Pitot theorem.[35]

More generally, a polygon with any number of sides that has an inscribed circle (that is, one that is tangent to each side) is called a tangential polygon.

Generalization to topological triangles

[edit]If you consider topological triangles, you can also define a notion of inscribed circle that fits inside. It is no longer described as tangent to all sides since your topological triangle might not be differentiable everywhere. Rather it is defined as a circle whose center has the same minimal distance to each side. Its a proven fact that an inscribed circle always exists in any topological triangle[36].

See also

[edit]- Circumcenter – Circle that passes through the vertices of a triangle

- Circumcircle – Circle that passes through the vertices of a triangle

- Circumconic and inconic – Conic section that passes through the vertices of a triangle or is tangent to its sides

- Circumgon – Geometric figure which circumscribes a circle

- Ex-tangential quadrilateral – Convex 4-sided polygon whose sidelines are all tangent to an outside circle

- Harcourt's theorem – Area of a triangle from its sides and vertex distances to any line tangent to its incircle

- Incenter–excenter lemma – Theorem about inscribed and circumscribed circles

- Inscribed sphere – Sphere tangent to every face of a polyhedron

- Power of a point – Relative distance of a point from a circle

- Steiner inellipse – Unique ellipse tangent to all 3 midpoints of a given triangle's sides

- Tangential quadrilateral – Polygon whose four sides all touch a circle

- Triangle conic

Notes

[edit]- ^ Kay (1969, p. 140)

- ^ a b Altshiller-Court (1925, p. 74)

- ^ a b c d e Altshiller-Court (1925, p. 73)

- ^ Kay (1969, p. 117)

- ^ a b Johnson 1929, p. 182.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers Archived 2012-04-19 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 2014-10-28.

- ^ Kay (1969, p. 201)

- ^ Chu, Thomas, The Pentagon, Spring 2005, p. 45, problem 584.

- ^ Allaire, Patricia R.; Zhou, Junmin; Yao, Haishen (March 2012), "Proving a nineteenth century ellipse identity", Mathematical Gazette, 96: 161–165, doi:10.1017/S0025557200004277, S2CID 124176398.

- ^ Altshiller-Court, Nathan (1980), College Geometry, Dover Publications. #84, p. 121.

- ^ Mathematical Gazette, July 2003, 323-324.

- ^ Kay (1969, p. 203)

- ^ Johnson 1929, p. 189, #298(d).

- ^ a b c d Bell, Amy. ""Hansen's right triangle theorem, its converse and a generalization", Forum Geometricorum 6, 2006, 335–342" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-08-31. Retrieved 2012-05-05.

- ^ Kodokostas, Dimitrios, "Triangle Equalizers", Mathematics Magazine 83, April 2010, pp. 141-146.

- ^ Posamentier, Alfred S., and Lehmann, Ingmar. The Secrets of Triangles, Prometheus Books, 2012.

- ^ a b c Franzsen, William N. (2011). "The distance from the incenter to the Euler line" (PDF). Forum Geometricorum. 11: 231–236. MR 2877263. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-12-05. Retrieved 2012-05-09..

- ^ Coxeter, H.S.M. "Introduction to Geometry 2nd ed. Wiley, 1961.

- ^ Minda, D., and Phelps, S., "Triangles, ellipses, and cubic polynomials", American Mathematical Monthly 115, October 2008, 679-689: Theorem 4.1.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Contact Triangle." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/ContactTriangle.html

- ^ Christopher J. Bradley and Geoff C. Smith, "The locations of triangle centers", Forum Geometricorum 6 (2006), 57–70. http://forumgeom.fau.edu/FG2006volume6/FG200607index.html Archived 2016-03-04 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dekov, Deko (2009). "Computer-generated Mathematics : The Gergonne Point" (PDF). Journal of Computer-generated Euclidean Geometry. 1: 1–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-05.

- ^ a b Altshiller-Court (1925, p. 79)

- ^ Kay (1969, p. 202)

- ^ Baker, Marcus, "A collection of formulae for the area of a plane triangle", Annals of Mathematics, part 1 in vol. 1(6), January 1885, 134-138. (See also part 2 in vol. 2(1), September 1885, 11-18.)

- ^ "Grinberg, Darij, and Yiu, Paul, "The Apollonius Circle as a Tucker Circle", Forum Geometricorum 2, 2002: pp. 175-182" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-06-25. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ "Stevanovi´c, Milorad R., "The Apollonius circle and related triangle centers", Forum Geometricorum 3, 2003, 187-195" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-10-06. Retrieved 2012-05-03.

- ^ Altshiller-Court (1925, pp. 103–110)

- ^ Kay (1969, pp. 18, 245)

- ^ Feuerbach, Karl Wilhelm; Buzengeiger, Carl Heribert Ignatz (1822), Eigenschaften einiger merkwürdigen Punkte des geradlinigen Dreiecks und mehrerer durch sie bestimmten Linien und Figuren. Eine analytisch-trigonometrische Abhandlung (in German) (Monograph ed.), Nürnberg: Wiessner.

- ^ Whitworth, William Allen. Trilinear Coordinates and Other Methods of Modern Analytical Geometry of Two Dimensions, Forgotten Books, 2012 (orig. Deighton, Bell, and Co., 1866). https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/search?q=%22Trilinear+coordinates%22

- ^ Nelson, Roger, "Euler's triangle inequality via proof without words", Mathematics Magazine 81(1), February 2008, 58-61.

- ^ Johnson 1929, p. 187.

- ^ "Emelyanov, Lev, and Emelyanova, Tatiana. "Euler's formula and Poncelet's porism", Forum Geometricorum 1, 2001: pp. 137–140" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-01-17. Retrieved 2012-05-02.

- ^ Josefsson (2011, See in particular pp. 65–66.)

- ^ Al-Ajrawi, Ezzaddin (20 October 2024). "Inscribing Spheres in Topologically Embedded Simplices". The American Mathematical Monthly. 131 (9): 806–813. doi:10.1080/00029890.2024.2380233. ISSN 0002-9890.

References

[edit]- Altshiller-Court, Nathan (1925), College Geometry: An Introduction to the Modern Geometry of the Triangle and the Circle (2nd ed.), New York: Barnes & Noble, LCCN 52013504

- Johnson, Roger A. (1929), "X. Inscribed and Escribed Circles", Modern Geometry, Houghton Mifflin, pp. 182–194

- Josefsson, Martin (2011), "More characterizations of tangential quadrilaterals" (PDF), Forum Geometricorum, 11: 65–82, MR 2877281, archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04, retrieved 2023-03-14

- Kay, David C. (1969), College Geometry, New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, LCCN 69012075

- Kimberling, Clark (1998). "Triangle Centers and Central Triangles". Congressus Numerantium (129): i–xxv, 1–295.

- Kiss, Sándor (2006). "The Orthic-of-Intouch and Intouch-of-Orthic Triangles". Forum Geometricorum (6): 171–177.

External links

[edit]- Derivation of formula for radius of incircle of a triangle, MATHalino

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Incircle". MathWorld.

Interactive

[edit]- Triangle incenter; Triangle incircle; Incircle of a regular polygon (with interactive animations)

- Constructing a triangle's incenter / incircle with compass and straightedge An interactive animated demonstration

- Equal Incircles Theorem at cut-the-knot

- Five Incircles Theorem at cut-the-knot

- Pairs of Incircles in a Quadrilateral at cut-the-knot

- An interactive Java applet for the incenter

Incircle and excircles

View on GrokipediaIncircle and Incenter

Definition of Incircle and Incenter

The incircle of a triangle is the unique circle that lies entirely within the triangle and is tangent to all three sides. It is also known as the inscribed circle and represents the largest circle that can fit inside the triangle while touching each side at exactly one point. This circle is a fundamental element in triangle geometry, providing insights into the triangle's internal structure and properties. The center of the incircle, termed the incenter, is the point of concurrency of the triangle's three angle bisectors. Each angle bisector divides the corresponding angle into two equal parts, and their intersection forms the incenter, which is equidistant from all three sides; this common distance is the inradius. The incenter thus serves as the geometric center of the incircle and plays a key role in various constructions and theorems related to triangle symmetry. The concepts of the incircle and incenter were first explored by ancient Greek mathematicians, with Euclid formalizing their properties in his Elements around 300 BCE. These early studies emphasized the incircle's role in balancing tangential contacts and area computations. For a triangle with side lengths , , and opposite vertices , , and respectively, the semiperimeter is defined as . The points where the incircle touches the sides divide each side into two segments: the lengths of the tangents from vertex to the points of tangency on sides and are both ; similarly, from they are , and from they are . This equal-tangent property ensures the incircle's balanced positioning and aids in visualizing its placement relative to the triangle's vertices.Coordinate Representations of Incenter

The incenter of a triangle can be precisely located using various coordinate systems, each offering distinct advantages for geometric computations and proofs. These systems include trilinear, barycentric, and Cartesian coordinates, which facilitate the analysis of the incenter's position relative to the triangle's vertices and sides. In trilinear coordinates, the incenter is represented as (1:1:1).[5] These coordinates are homogeneous, meaning they are defined up to scalar multiplication, and they correspond to the signed distances from the point to the triangle's sides, normalized relative to the side lengths. For the incenter, the equal distances to all three sides (equal to the inradius) result in this symmetric form, making trilinear coordinates particularly suited for problems involving perpendicular distances and cevian intersections.[6] Barycentric coordinates provide another homogeneous representation of the incenter as (a:b:c), where a, b, and c denote the lengths of the sides opposite vertices A, B, and C, respectively.[5] This form arises from the relation between trilinear and barycentric systems: the barycentric coordinates are obtained by multiplying the trilinear coordinates by the corresponding side lengths, yielding (a·1 : b·1 : c·1) = (a:b:c).[7] The derivation stems from viewing the incenter as the center of mass of the triangle's vertices weighted by the opposite side lengths, reflecting the balance achieved at the intersection of the angle bisectors.[8] Specifically, if A, B, and C are the position vectors of the vertices, the incenter I satisfies I = (aA + bB + cC) / (a + b + c).[5] In Cartesian coordinates, assuming the triangle has vertices A(x_A, y_A), B(x_B, y_B), and C(x_C, y_C), the incenter's position is given by This formula directly extends the barycentric representation to Euclidean space, allowing for numerical computation and visualization in a plane.[5] Each coordinate system has specific computational benefits: trilinear coordinates excel in derivations involving side distances and homogeneous properties, barycentric coordinates are advantageous for mass point geometry and affine-invariant calculations (such as balancing cevians in the incenter example with weights proportional to side lengths), while Cartesian coordinates are ideal for direct metric computations and plotting in standard geometry software.[9]Inradius Formula and Derivation

The inradius of a triangle is the radius of its incircle, which touches all three sides internally. It is given by the formula , where is the area of the triangle and is the semiperimeter, with , , and denoting the side lengths.[4][10] To derive this formula, consider the incenter , the center of the incircle. The points of tangency divide the sides into segments equal to the tangent lengths from each vertex. The triangle's area can be decomposed into the three smaller triangles formed by connecting to the vertices: , , and . However, a more straightforward approach uses the tangential regions: the area is the sum of the areas of three right triangles (or sectors in a limiting sense, but precisely via perpendiculars) from to each side. Each such region has height (the perpendicular distance from to the side) and base equal to the side length, yielding Solving for gives . This derivation relies on the property that the incircle is tangent to all sides, ensuring equal perpendicular distances.[10][11][12] An alternative expression for the inradius is , where is the angle at vertex opposite side . To derive this, note that the lengths of the tangents from vertex to the points of tangency on sides and are both . The angle bisector from passes through , splitting into two equal angles of . Consider the right triangle formed by vertex , the point of tangency on , and the foot of the perpendicular from to : the adjacent side to is , and the opposite side is , so , hence . Similar expressions hold for the other angles.[4][13] This relation integrates historically with Heron's formula for the area, , attributed to Heron of Alexandria in the 1st century CE. Substituting yields , providing a side-length-only expression for without explicit area computation. Early proofs of Heron's formula, such as those using cyclic quadrilaterals or trigonometric identities, often leverage the inradius to bridge perimeter and area concepts, emphasizing the incircle's role in partitioning the triangle's area into equal-tangent components.[4][14] For an equilateral triangle with side length , the area is and , so . This illustrates the formula's application, where the inradius is one-third of the height .[4]Properties of Incircle Touch Points

The points where the incircle of a triangle touches the sides are known as the points of tangency. For a triangle with side lengths , , , and semiperimeter , denote the points of tangency on sides , , and by , , and , respectively. The lengths of the tangent segments from each vertex to the points of tangency are equal, a property arising from the fact that tangents drawn from a common external point to a circle are congruent.[15] Thus, the distance from vertex to (on ) equals the distance from to (on ), denoted . Similarly, the distance from to (on ) equals the distance from to (on ), denoted , and the distance from to (on ) equals the distance from to (on ), denoted . These relations follow directly from solving the system of equations for the side lengths: , , , yielding , and analogously for and .[15] The positions of the touch points on the sides can thus be specified: divides such that and ; divides such that and ; divides such that and . These distances represent the segments from the vertices to the nearest touch points along the adjacent sides.[15] The three touch points , , and form a triangle known as the contact triangle (or intouch triangle), which is perspective to the reference triangle . The sides of the contact triangle are tangent to the incircle at , , and , and its vertices lie on the sides of .[16] The cevians joining each vertex of to the opposite touch point (, , ) are concurrent at the Gergonne point.Excircles and Excenters

Definition of Excircles and Excenters

In a triangle, an excircle (or escribed circle) is a circle that lies outside the triangle and is tangent to one of its sides and to the extensions of the other two sides. Every triangle has three distinct excircles, one opposite each vertex; for instance, the excircle opposite vertex A (denoted the A-excircle) is tangent to side BC at a point and to the infinite extensions of sides AB and AC beyond points B and C, respectively. The excenter of an excircle is its center, which serves as the point of concurrency for specific angle bisectors of the triangle. The three excenters, labeled , , and opposite vertices A, B, and C respectively, are each formed by the intersection of the internal angle bisector from one vertex and the external angle bisectors from the other two. Specifically, lies at the intersection of the internal bisector of and the external bisectors of and .[17] Unlike the incircle, which touches all three sides internally from within the triangle, each excircle touches one side directly and the extensions of the others from the exterior, resulting in a larger radius and positioning the circle outside the triangle opposite the associated vertex. This external configuration distinguishes the excircles as counterparts to the internal incircle in the study of tangential circles to a triangle.Coordinate Representations of Excenters

The excenters of a triangle can be expressed using trilinear coordinates, which are homogeneous coordinates proportional to the directed distances from the point to the sides of the triangle. The excenter opposite vertex , denoted , has trilinear coordinates , where , , and are the lengths of the sides opposite vertices , , and respectively. The negative sign for the -coordinate reflects the external position of relative to side , as it lies outside the triangle on the extension of the angle bisector from . Similarly, the excenter opposite has coordinates , and opposite has .[18] Barycentric coordinates provide another homogeneous representation for the excenters, closely related to trilinear coordinates by normalization with respect to the triangle's area. For , the barycentric coordinates are , interpreted as signed masses placed at the vertices: a negative mass at and positive masses at and , whose center of mass yields the excenter. To obtain normalized barycentric coordinates summing to 1, divide by the total weight: the coordinates become . The cyclic permutations apply analogously for and , with the negative sign indicating the vertex opposite the excircle's internal tangency.[19] In Cartesian coordinates, the position of an excenter follows directly from the barycentric representation as a weighted average of the vertices' positions. For , with vertices , , and , the coordinates are This formula arises by applying the signed weights from the barycentric coordinates to the vertex positions and normalizing by the sum of the weights, providing an explicit embedding in the plane. The same weighted average structure holds for and with their respective sign flips.[19] The three excenters , , and form the vertices of the excentral triangle, a triangle whose orthocenter is the incenter of the original triangle.[20]Exradii Formulas and Derivation

The exradii of a triangle are the radii of its excircles, denoted , , and , opposite vertices , , and respectively. Let be the area of the triangle and its semiperimeter. The formulas are , , and , where , , and are the side lengths opposite , , and .[21] To derive these, consider the excircle opposite , tangent to side internally and to the extensions of and externally. The excenter forms three tangential triangles with the sides: (internal tangent), and , (external tangents). Consider the areas of the tangential triangles. The area of equals the area of plus the area of minus the area of . Each area is times the base times the height , yielding . Thus, ; the other exradii follow cyclically.[22][21] An alternative expression is , with cyclic permutations for and . To derive this using the extended law of sines, note that the excenter lies on the internal angle bisector of . Consider the right triangle formed by , the touch point on the extension of , and the foot of the perpendicular from to . The adjacent side to (half-angle along the bisector) is the tangent length from to the touch point, which equals , and the opposite side is . Thus, , so . The extended law of sines confirms consistency via , linking to half-angle identities, but the bisector geometry provides the direct proof.[21] The exradii relate to the inradius by . This follows from the area expressions: , and summing yields .[21] For example, in a right triangle with sides 3, 4, 5 (, , ), assume the right angle at C opposite the hypotenuse c = 5, with a = 4, b = 3; the exradii are , , . These exceed , with largest opposite the longest side, and satisfy . For the right angle , .[21]Properties of Excircle Touch Points

The A-excircle of triangle , with sides , , , and semiperimeter , touches side internally at point such that the distance from to is and from to is .[23] This placement ensures that the tangent segments from and to the point of tangency are equal, consistent with the properties of tangents from a point to a circle. The A-excircle touches the extension of side beyond at point and the extension of side beyond at point . The distance from to is , so the distance from to along the extension is ; similarly, the distance from to is , so the distance from to is .[23] These tangent lengths from vertex equal the semiperimeter , while the lengths from and are and , respectively; on extensions, distances are measured positively outward from the vertices, with signed lengths accounting for direction in coordinate geometries (positive for extensions beyond and , negative if considering directions toward ). The touch points of the three excircles with the sides of the triangle—one per side—form the extouch triangle, also known as the extangents triangle, which exhibits properties such as being the cevian triangle of the Nagel point and having side lengths derived from the original triangle's dimensions, like for the side opposite the vertex corresponding to side .[24] This triangle arises directly from the excircle tangency points on the sides and encapsulates semiperimeter relations, where the positions divide the perimeter such that the arc lengths along the sides relate to , , and in aggregate. These excircle touch points play a key geometric role in constructing tangential quadrilaterals, as the positions on the side extensions and the internal touch allow the excircle to serve as the incircle for a quadrilateral formed by the three triangle sides and an additional tangent line connecting the external touch points, enabling derivations of quadrilateral properties via triangle excircle tangencies.[23] The semiperimeter governs these lengths, with the total effective tangent path from across both extensions equaling , underscoring the excircle's relation to the triangle's perimeter.Related Geometric Constructions

Gergonne and Nagel Points and Triangles

The Gergonne point of a triangle is the point of concurrency of the three cevians joining each vertex to the point of tangency of the incircle with the opposite side.[25] This concurrency follows from Ceva's theorem applied to the side divisions induced by the touch points, where the ratios satisfy (s-b)/ (s-c) · (s-c)/(s-a) · (s-a)/(s-b) = 1, with s denoting the semiperimeter.[25] In barycentric coordinates with respect to the reference triangle, the Gergonne point has coordinates ((s-b)(s-c) : (s-c)(s-a) : (s-a)(s-b)), or equivalently (1/(s-a) : 1/(s-b) : 1/(s-c)) up to scalar multiple.[25] The Gergonne triangle, also known as the intouch triangle or contact triangle, is the triangle formed by connecting the three points of tangency of the incircle with the sides of the reference triangle.[26] This triangle is perspective to the reference triangle, with the Gergonne point serving as the perspector; the lines joining corresponding vertices pass through this concurrency point.[25] The Nagel point is defined analogously as the point of concurrency of the cevians from each vertex to the point of tangency of the excircle opposite that vertex with the opposite side (extended if necessary).[27] Ceva's theorem again confirms this concurrency, with the relevant ratios (s-a)/s · s/(s-b) · (s-b)/(s-a) = 1, though adjusted for the external divisions.[25] Its barycentric coordinates are (s-a : s-b : s-c).[25] The Nagel point is also known as the isotomic conjugate of the incenter and relates to the splitters, which are the cevians to the excircle touch points.[27] The Nagel triangle, or extouch triangle, is formed by the three points where the excircles touch the sides of the reference triangle (on extensions for the external tangencies).[28] Like the Gergonne triangle, it is perspective to the reference triangle, with the Nagel point as the perspector.[25] The Gergonne and Nagel points are isotomic conjugates of each other, as their barycentric coordinates are reciprocals: the transformation (x : y : z) \mapsto (1/x : 1/y : 1/z) maps one to the other.[25] In an equilateral triangle, both points coincide with the centroid, incenter, orthocenter, and other classical centers, all lying on the Euler line.[25] The distance between the Gergonne and Nagel points can be expressed using barycentric distance formulas, yielding a quantity dependent on the side lengths a, b, c and semiperimeter s, though it establishes no unique geometric invariant beyond their conjugate relation.[29]Incentral and Excentral Triangles

The incentral triangle is formed by the incenter I and the three excenters I_a, I_b, I_c of a reference triangle ABC. These four points constitute an orthocentric system, in which each point serves as the orthocenter of the triangle formed by the other three.[30] In this system, the reference triangle ABC functions as the orthic triangle of the excentral triangle (the triangle formed by the three excenters), with the altitudes from the excenters to the opposite sides landing at the vertices of ABC.[20] The excentral triangle, denoted ΔI_aI_bI_c, has vertices at the three excenters of ABC. It is always acute-angled, with angles measuring 90° - A/2 at I_a, 90° - B/2 at I_b, and 90° - C/2 at I_c.[31] The orthocenter of the excentral triangle coincides with the incenter I of the original triangle ABC.[32] Its side lengths are given by I_bI_c = 4R \cos(A/2), I_aI_c = 4R \cos(B/2), and I_aI_b = 4R \cos(C/2), where R is the circumradius of ABC; these can be related to the exradii r_a, r_b, r_c via the formula r_a = 4R \sin(A/2) \cos(B/2) \cos(C/2), though direct expressions in terms of exradii alone are more complex.[32] The excentral triangle's incircle has radius 2R (\sin(A/2) + \sin(B/2) + \sin(C/2) - 1), where R is the circumradius of ABC, establishing its scale relative to the original triangle.[33] The excentral triangle is homothetic to the intouch triangle (the contact triangle of the incircle of ABC), with the center of homothety being the isogonal conjugate of the Mittenpunkt; this transformation highlights similarities in their cevian structures and tangency properties.[34]Feuerbach Point and Nine-Point Circle Relations

The Feuerbach point of a triangle is the point of tangency between the incircle and the nine-point circle, where the incircle touches the nine-point circle internally.[35] This point was identified as part of Feuerbach's theorem, published by Karl Wilhelm Feuerbach in his 1822 work Eigenschaften des Dreiecks, which establishes the tangential relations among the incircle, excircles, and nine-point circle.[36] Feuerbach's theorem states that the nine-point circle is internally tangent to the incircle at the Feuerbach point and externally tangent to each of the three excircles at distinct points, known collectively as forming the Feuerbach triangle.[35] These tangency points exhibit specific geometric properties, with the Feuerbach point serving as a triangle center, denoted X(11) in the Encyclopedia of Triangle Centers.[35] In barycentric coordinates with respect to the reference triangle, the Feuerbach point has coordinates , where are the side lengths opposite angles respectively.[35] An alternative algebraic form is .[35] The points of tangency with the excircles, while separate, share analogous properties and lie on the Feuerbach triangle, which connects these external tangencies.[35] Feuerbach's theorem provides historical context for these tangencies, originating from Feuerbach's systematic study of triangle properties in 1822, including proofs of the nine-point circle's contacts with the incircle and excircles using properties of the orthocenter and midpoints.[36] This theorem highlights concurrencies in triangle geometry, such as the alignment of the nine-point center with other key points.[37] These relations extend to broader configurations, including the Euler line, where the nine-point center—midpoint of the segment joining the orthocenter and circumcenter—facilitates the tangential properties of the Feuerbach point and related tangencies.[38] In circle packings, the incircle, excircles, and nine-point circle form a tangential system that influences other packs, such as those involving the intouch triangle, where the Feuerbach point aligns with the Euler line of the intouch triangle itself.[39]Advanced Formulas and Theorems

Equations of the Four Circles

The incircle and excircles of a triangle can be described by their equations in Cartesian coordinates using the positions of their centers and radii. The general equation of a circle in the plane is , where is the center and is the radius. For a triangle with vertices , , , and side lengths , , opposite these vertices respectively, the incenter has Cartesian coordinates derived from its barycentric coordinates : The equation of the incircle is then , where is the inradius.[35] The excenters similarly arise from signed barycentric coordinates. The excenter opposite vertex has barycentric coordinates , yielding Cartesian coordinates and its equation is , where is the exradius opposite . Analogous forms hold for the excenters (barycentrics ) and (barycentrics ), incorporating the negative weight for the opposite side into the denominator and numerator of the weighted averages.[35][19] These four circles admit a unified parametric representation through their centers' barycentric coordinates , where each : all positive for the incenter, and negative for the coordinate corresponding to the opposite vertex in each excenter. The Cartesian coordinates of any such center are obtained by normalizing these barycentrics as weighted averages of the vertex positions, with the circle equation following from the appropriate radius. This signed weighting reflects the internal tangency of the incircle versus the external tangency of the excircles to one side.[19]Euler's Distance Formula

Euler's distance formula gives the squared distance between the circumcenter and the incenter of a triangle as , where is the circumradius and is the inradius.[40] This relation highlights the geometric interplay between the triangle's circumcircle and incircle centers. The formula extends to the excenters, with the squared distance between the circumcenter and the excenter (opposite vertex ) given by , where is the exradius opposite .[41] Similar expressions hold for the other excenters and . Related distances include that between the incenter and an excenter , which satisfies .[42] This form arises from coordinate geometry or trigonometric identities linking the radii and angles. Historically, the formula is attributed to Leonhard Euler's work on triangle centers in 1765, though an earlier discovery by Robert Chapple in 1746 is noted; modern proofs often employ complex number representations of triangle points for elegance and brevity.[43]Derivation

One derivation of uses trigonometric identities. The distance can be expressed as . Since the inradius , substituting yields .[40] For the excenter extension, a similar trigonometric approach applies, replacing the inradius with the exradius in the identity, leading to the positive sign due to the external angle bisectors. Vector formulations position and compute the norm relative to , confirming the result after algebraic simplification.[44] Although the nine-point circle relates the circumcenter to the orthocenter, its midpoint (the nine-point center) aids indirect derivations via Euler line properties, but the direct trigonometric or vector methods are more straightforward for the incenter-excenter distances.[45]Generalizations to Polygons and Topological Figures

A tangential polygon, also known as an inscriptible or circumscriptible polygon, is one that possesses an incircle tangent to all its sides. Such polygons exist when the sums of the lengths of every other side are equal, generalizing the condition for triangles where the incircle is always present. The inradius of a tangential polygon with area and semiperimeter is given by .[4] For regular -gons, the incircle's radius coincides with the apothem, the distance from the center to a side, providing a straightforward geometric interpretation. However, excircles—circles tangent to one side and the extensions of the remaining sides—are primarily defined for triangles and do not generalize directly to polygons with more than three sides in the same unique manner. Analogs known as escribed circles can be constructed for certain polygons, tangent to one side and the extensions of the others, but their existence depends on specific side length conditions and is not guaranteed for all tangential polygons. For instance, convex pentagons and higher can be designed to admit at least one such circle, though this requires tailored constructions rather than a universal property.[3] In higher-dimensional Euclidean spaces, the concepts extend to simplices, where an insphere is tangent to all facets of an -simplex. Every simplex admits a unique insphere, with its center (incenter) being the point equidistant from all facets, located at the intersection of the angle bisectors in the appropriate sense or via barycentric coordinates weighted by facet areas. Exspheres analogously exist, each tangent to one facet and the extensions of the others, up to such spheres for an -simplex. These structures are utilized in computational geometry, particularly in Delaunay triangulations, where the incircle test—verifying if a circle through three points contains no other points—determines triangulation edges, linking incircles to Voronoi diagrams as dual constructs.[46][47][48] Beyond Euclidean geometry, incircles and excircles generalize to non-Euclidean settings, such as hyperbolic triangles, which always possess an incircle tangent to all three sides, with the incenter at the intersection of the angle bisectors. Up to three excircles may also exist, depending on the triangle's configuration, determined similarly by internal and external bisectors. In metric spaces or topological figures, such as topologically embedded simplices, inscribed spheres can be defined via tangency conditions adapted to the ambient geometry, though uniqueness may fail in curved or discrete spaces without additional constraints. These generalizations appear in applications like hyperbolic tilings and computational simulations of curved manifolds.[49]References

- https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Trigonometry/Circles_and_Triangles/The_Excircles

- https://en.wikibooks.org/wiki/Trigonometry/Circles_and_Triangles/The_Excentral_Triangle

![{\displaystyle {\overline {OI}}^{2}=R(R-2r)={\frac {a\,b\,c\,}{a+b+c}}\left[{\frac {a\,b\,c\,}{(a+b-c)\,(a-b+c)\,(-a+b+c)}}-1\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bb15cf80e70231de35ac2c6a332123c6e5ab377a)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{ccccccc}T_{A}&=&0&:&\sec ^{2}{\frac {B}{2}}&:&\sec ^{2}{\frac {C}{2}}\\[2pt]T_{B}&=&\sec ^{2}{\frac {A}{2}}&:&0&:&\sec ^{2}{\frac {C}{2}}\\[2pt]T_{C}&=&\sec ^{2}{\frac {A}{2}}&:&\sec ^{2}{\frac {B}{2}}&:&0.\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9eb7b01b64eee3aa88c531ac3c509a1297330fb5)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\Delta &={\tfrac {1}{4}}{\sqrt {-a^{4}-b^{4}-c^{4}+2a^{2}b^{2}+2b^{2}c^{2}+2a^{2}c^{2}}}\\[5mu]&={\tfrac {1}{4}}{\sqrt {(a+b+c)(-a+b+c)(a-b+c)(a+b-c)}}\\[5mu]&={\sqrt {s(s-a)(s-b)(s-c)}},\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e17e05c79be64264f2af1be5ecf1d02950827252)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&r_{a}^{2}={\frac {s(s-b)(s-c)}{s-a}}\\[4pt]&\implies r_{a}={\sqrt {\frac {s(s-b)(s-c)}{s-a}}}.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ba686fd7b853925eb08592fc095e9bf4b0113bb9)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{ccccccc}T_{A}&=&0&:&\csc ^{2}{\frac {B}{2}}&:&\csc ^{2}{\frac {C}{2}}\\[2pt]T_{B}&=&\csc ^{2}{\frac {A}{2}}&:&0&:&\csc ^{2}{\frac {C}{2}}\\[2pt]T_{C}&=&\csc ^{2}{\frac {A}{2}}&:&\csc ^{2}{\frac {B}{2}}&:&0\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0e8d6799e9e4d5b1aea79376040b10da869f6dcb)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{ccccccc}A'&=&0&:&1&:&1\\[2pt]B'&=&1&:&0&:&1\\[2pt]C'&=&1&:&1&:&0\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3487b5cc7e4da69320fd2b2eba8694f84f687ceb)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{array}{ccrcrcr}A'&=&-1&:&1&:&1\\[2pt]B'&=&1&:&-1&:&1\\[2pt]C'&=&1&:&1&:&-1\end{array}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a64e38d71f55286a611e6ba91d8f7b53ad1c582f)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}u^{2}x^{2}+v^{2}y^{2}+w^{2}z^{2}-2vwyz-2wuzx-2uvxy&=0\\[4pt]{\textstyle \pm {\sqrt {x}}\cos {\tfrac {A}{2}}\pm {\sqrt {y{\vphantom {t}}}}\cos {\tfrac {B}{2}}\pm {\sqrt {z}}\cos {\tfrac {C}{2}}}&=0\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f2920e55669ed2026e6f5d95a18597f2ffe1a260)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}u^{2}x^{2}+v^{2}y^{2}+w^{2}z^{2}-2vwyz+2wuzx+2uvxy&=0\\[4pt]{\textstyle \pm {\sqrt {-x}}\cos {\tfrac {A}{2}}\pm {\sqrt {y{\vphantom {t}}}}\cos {\tfrac {B}{2}}\pm {\sqrt {z}}\cos {\tfrac {C}{2}}}&=0\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2d03601071be1531bd0bbbe1ed9d44f8c8bba2b1)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}u^{2}x^{2}+v^{2}y^{2}+w^{2}z^{2}+2vwyz-2wuzx+2uvxy&=0\\[4pt]{\textstyle \pm {\sqrt {x}}\cos {\tfrac {A}{2}}\pm {\sqrt {-y{\vphantom {t}}}}\cos {\tfrac {B}{2}}\pm {\sqrt {z}}\cos {\tfrac {C}{2}}}&=0\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5c44c4ca2ef6fee4eca0fa7e8a92d3e400f4266b)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}u^{2}x^{2}+v^{2}y^{2}+w^{2}z^{2}+2vwyz+2wuzx-2uvxy&=0\\[4pt]{\textstyle \pm {\sqrt {x}}\cos {\tfrac {A}{2}}\pm {\sqrt {y{\vphantom {t}}}}\cos {\tfrac {B}{2}}\pm {\sqrt {-z}}\cos {\tfrac {C}{2}}}&=0\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e28aa20f8675ce4680149c36f52266ceca04eeff)