Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Foundation IRB

View on WikipediaThis article includes a list of references, related reading, or external links, but its sources remain unclear because it lacks inline citations. (April 2025) |

| Basel Framework International regulatory standards for banks |

|---|

| Background |

| Pillar 1: Regulatory capital |

| Pillar 2: Supervisory review |

| Pillar 3: Market disclosure |

| Business portal |

The term Foundation IRB or F-IRB is an abbreviation of foundation internal ratings-based approach, and it refers to a set of credit risk measurement techniques proposed under Basel II capital adequacy rules for banking institutions.

Under this approach the banks are allowed to develop their own empirical model to estimate the PD (probability of default) for individual clients or groups of clients. Banks can use this approach only subject to approval from their local regulators.

Under F-IRB banks are required to use regulator's prescribed LGD (Loss Given Default) and other parameters required for calculating the RWA (Risk-Weighted Asset) for non-retail portfolios. For retail exposures banks are required to use their own estimates of the IRB parameters (PD, LGD, CCF). Then total required capital is calculated as a fixed percentage of the estimated RWA.

Reforms to the internal ratings-based approach to credit risk are due to be introduced under the Basel III: Finalising post-crisis reforms.

Some formulae in internal-ratings-based approach

[edit]Some credit assessments in standardised approach refer to unrated assessment. Basel II also encourages banks to initiate internal ratings-based approach for measuring credit risks. Banks are expected to be more capable of adopting more sophisticated techniques in credit risk management.

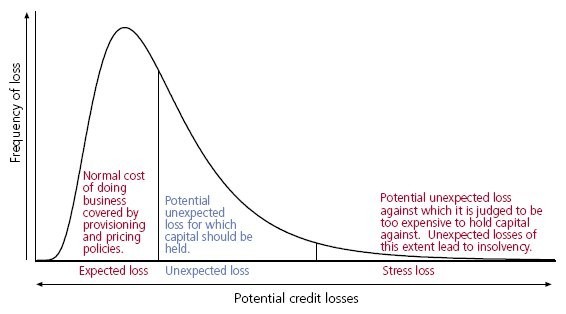

Banks can determine their own estimation for some components of risk measure: the probability of default (PD), exposure at default (EAD) and effective maturity (M). The goal is to define risk weights by determining the cut-off points between and within areas of the expected loss (EL) and the unexpected loss (UL), where the regulatory capital should be held, in the probability of default. Then, the risk weights for individual exposures are calculated based on the function provided by Basel II.

Below are the formulae for some banks' major products: corporate, small-medium enterprise (SME), residential mortgage and qualifying revolving retail exposure.

Notes:

- 10 Function is taken from paragraph 272

- 11 Function is taken from paragraph 273

- 12 Function is taken from paragraph 328

- 13 Function is taken from paragraph 229

- PD = the probability of default

- LGD = loss given default

- EAD = exposure at default

- M = effective maturity

Advantages

[edit]Basel-II benefits customers with lower probability of default. Basel-II benefits banks to hold lower capital requirement as having corporate customers with lower probability of default (Graph 1).

Basel-II benefits SME customers to be treated differently from corporates.

Basel-II benefits banks to hold lower capital requirement as having credit card product customers with lower probability of default (Graph 2).

Basel-II benefits SME customers to be treated differently from corporates.

Basel-II benefits banks to hold lower capital requirement as having credit card product customers with lower probability of default (Graph 2).

References

[edit]- Basel II: Revised international capital framework (BCBS)

- Basel II: International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: a Revised Framework (BCBS)

- Basel II: International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: a Revised Framework (BCBS) (November 2005 Revision)

- Basel II: International Convergence of Capital Measurement and Capital Standards: a Revised Framework, Comprehensive Version (BCBS) (June 2006 Revision)

Foundation IRB

View on GrokipediaIntroduction and Definition

Overview

The Foundation Internal Ratings-Based (F-IRB) approach is a regulatory framework for calculating credit risk capital requirements in banking, introduced under the Basel II Accord in 2004.[1] It allows eligible banks to use internal models to estimate the probability of default (PD) for credit exposures, while relying on prescribed supervisory values for other risk parameters such as loss given default (LGD), exposure at default (EAD), and effective maturity (M).[4] This hybrid method aims to enhance the risk sensitivity of capital calculations compared to the standardized approach, without granting banks full discretion over all parameters as in the advanced IRB (A-IRB) variant.[5] F-IRB applies primarily to corporate, sovereign, and bank exposures, with banks required to meet stringent minimum data, methodological, and governance standards for PD estimation, as outlined by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS).[6] Risk-weighted assets (RWAs) under F-IRB are derived from Basel-specified risk-weight functions that incorporate the bank's PD inputs alongside fixed LGD assumptions (e.g., 45% for senior unsecured corporate claims) and other supervisory inputs.[1] Adoption of F-IRB requires prior supervisory approval, ensuring consistent and verifiable risk quantification across institutions.[7] The approach balances innovation in risk management with regulatory prudence, mitigating model risk by limiting bank-specific estimates to PD, which is considered the most observable and data-rich parameter.[8] Subsequent Basel reforms, including Basel III and the finalization of Basel IV in 2017, have imposed output floors and parameter constraints on F-IRB to address variability in RWAs and enhance comparability, with implementation phased in from 2023 onward in major jurisdictions.[3]Relation to Basel Accords

The Foundation Internal Ratings-Based (F-IRB) approach forms a core component of the credit risk framework established under the Basel II Accord, which was finalized by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) in June 2004 and became effective from January 2007 in many jurisdictions.[9] This accord introduced the IRB approaches as alternatives to the standardized approach, enabling banks to use internal estimates for certain risk parameters to derive more risk-sensitive regulatory capital requirements under Pillar 1.[10] Unlike the standardized method, which relies solely on external credit ratings and fixed risk weights, F-IRB allows institutions to incorporate their own data-driven assessments of borrower creditworthiness, thereby aiming to better align capital holdings with underlying economic risks based on empirical loss data.[11] In the F-IRB variant, banks are permitted to develop and use internal rating systems primarily for estimating the probability of default (PD) for individual obligors or groups of obligors, subject to supervisory approval and minimum data requirements such as at least five years of default history.[1] However, other key risk components—loss given default (LGD), exposure at default (EAD), and effective maturity (M)—are prescribed by supervisors to ensure conservatism and comparability across institutions. For example, under F-IRB for corporate exposures, LGD is set at 45%, reflecting a long-run average informed by historical recovery rates, while M defaults to 2.5 years unless adjusted based on loan terms.[12] These supervisory parameters mitigate model risk and prevent underestimation of losses, drawing from aggregated industry data rather than bank-specific models, which are reserved for the more advanced IRB (A-IRB) approach.[11] The F-IRB approach's risk-weighted assets (RWA) are calculated using a supervisory formula that integrates PD with the fixed parameters, incorporating asset correlation assumptions derived from econometric models of default clustering during economic downturns.[11] This formula, calibrated to require approximately 8% capital for a standard portfolio (similar to Basel I's target), emphasizes downturn loss rates to capture cyclical vulnerabilities, promoting financial stability without excessive reliance on unverified internal data.[12] Basel II's IRB framework, including F-IRB, was designed to reward banks with robust risk management practices while maintaining a level playing field through standardized elements, though implementation revealed challenges in PD estimation accuracy and supervisory validation.[9] Subsequent Basel Accords, such as Basel III (2010-2011), retained the F-IRB structure within Pillar 1 but overlaid additional buffers and liquidity requirements to address procyclicality exposed by the 2008 financial crisis, without fundamentally altering the core IRB mechanics. Basel III's enhancements focused on output floors and higher quality capital, indirectly constraining IRB benefits by capping risk-weight reductions relative to standardized approaches.[11] Thus, F-IRB remains integrated into the evolving Basel standards, serving as a bridge between standardized rigidity and advanced modeling flexibility.Historical Development

Introduction in Basel II

The Basel II framework, finalized by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision in June 2004, introduced the Internal Ratings-Based (IRB) approach as a key innovation for measuring credit risk in Pillar 1 capital requirements.[13] This approach allowed qualifying banks to use internal models for risk-weighted assets (RWAs), replacing the more rigid standardized method of Basel I with greater risk sensitivity. The IRB method comprised two variants: the Foundation IRB (F-IRB) and the Advanced IRB (A-IRB), enabling banks with developed internal rating systems to align capital charges more closely with underlying portfolio risks.[14] Under the Foundation IRB, banks were required to estimate the probability of default (PD) internally for individual borrowers or pools, based on their own rating systems, while relying on supervisory estimates for other risk parameters: loss given default (LGD) at 45% for senior unsecured claims, exposure at default (EAD) via prescribed methods, and effective maturity (M) calculated using a formula incorporating loan terms.[11] This hybrid structure balanced banks' expertise in default prediction with regulatory safeguards to ensure conservatism and comparability across institutions. Eligibility for F-IRB mandated robust data, processes, and validation of internal PD models, subject to supervisory approval, with minimum requirements outlined in the framework's operational criteria.[12] The introduction of Foundation IRB aimed to incentivize investment in risk management infrastructure, particularly for corporate, sovereign, and bank exposures, while mitigating moral hazard by limiting internal estimates to PD alone.[11] Implementation timelines varied by jurisdiction; for instance, the European Union directed adoption from January 1, 2007, for credit institutions, whereas the United States finalized rules in December 2007, effective April 2008, with parallel runs to assess impacts.[15][16] This phased rollout allowed regulators to calibrate the approach amid concerns over potential capital reductions for certain portfolios, ensuring systemic stability.Evolution in Basel III and IV

The Basel III framework, published by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) in December 2010 and revised through 2011, retained the Foundation Internal Ratings-Based (F-IRB) approach for credit risk as introduced in Basel II, with minimal direct modifications to its core parameters. Banks continued to estimate probability of default (PD) internally while relying on supervisory values for loss given default (LGD, typically 45% for senior unsecured corporate exposures) and exposure at default (EAD). However, Basel III imposed broader constraints, including enhanced minimum data and validation requirements for IRB models to improve robustness post-2008 financial crisis, alongside higher overall capital ratios (e.g., minimum Common Equity Tier 1 ratio increased to 4.5% from 2% in Basel II) that indirectly elevated effective requirements for F-IRB users.[17] These changes aimed to address model shortcomings revealed during the crisis, such as underestimation of tail risks, without overhauling F-IRB mechanics.[18] The most substantial evolution occurred in the BCBS's finalization of Basel III post-crisis reforms, released on December 7, 2017, and commonly termed Basel IV, which targeted excessive variability in risk-weighted assets (RWAs) across banks using internal models. For F-IRB, the reforms prohibited the Advanced IRB (A-IRB) approach for certain high-risk exposures, mandating F-IRB or the standardised approach instead: specifically, A-IRB was eliminated for large corporate exposures (annual revenues exceeding €500 million) and financial institutions, channeling banks toward F-IRB's supervisory LGD and EAD parameters to enhance comparability and conservatism.[19] Revised risk weight functions incorporated updated correlation formulas (e.g., reducing asset correlation multipliers for low-default portfolios) and introduced PD input floors (e.g., 0.03% for most corporate exposures) to curb optimistic internal estimates, while LGD estimates in defaulted exposures were standardized at 8% recovery rate floors for purchased receivables.[17] Equity exposures were fully removed from IRB eligibility, requiring standardised treatment.[20] A key innovation was the aggregate output floor, limiting total RWAs calculated under IRB approaches (including F-IRB) to no less than 72.5% of those derived from the standardised approach, applied portfolio-wide rather than per exposure. This floor, intended to mitigate undue capital relief from internal models—where F-IRB RWAs had historically varied by up to 30-50% across peers—phases in over five years starting January 1, 2025 (at 50% initially, reaching 72.5% by 2030 in jurisdictions like the EU).[17][21] The 1.06 scaling factor from Basel II was eliminated, further aligning IRB outputs with standardised benchmarks. These measures collectively reduced F-IRB's flexibility, prioritizing regulatory consistency over bank-specific modeling, with quantitative impact studies showing average RWA increases of 20-30% for IRB-reliant banks.[18] Implementation varies by jurisdiction, with the EU adopting via CRR III/CRD VI effective 2025, while the U.S. Federal Reserve integrates elements into its tailoring framework.[22]Technical Components

Risk Parameters

In the Foundation IRB approach under Basel II, banks calculate risk-weighted assets using four primary risk parameters: Probability of Default (PD), Loss Given Default (LGD), Exposure at Default (EAD), and Effective Maturity (M). These parameters feed into standardized risk weight functions that determine capital requirements for credit risk. Unlike the Advanced IRB approach, Foundation IRB limits bank discretion by requiring supervisory estimates for LGD, certain EAD components, and M, while allowing internal PD estimation subject to regulatory approval and validation. This hybrid structure aims to balance risk sensitivity with supervisory control to mitigate model risk.[23][1] PD represents the bank's internal estimate of the likelihood that a borrower will default within a one-year horizon, expressed as a percentage and calibrated to long-run average default rates for each internal rating grade. Banks must demonstrate robust data history—typically at least five years for corporates—and ensure PD estimates are granular, forward-looking where appropriate, and validated against observed defaults. Supervisory floors apply, such as a minimum PD of 0.03% for strong grades, to prevent underestimation. PD estimation is central to Foundation IRB's risk sensitivity, as higher PD grades directly increase risk weights via the IRB formula's asset correlation term, which assumes systematic risk factors (e.g., 12-24% correlation for corporates depending on PD level).[23][11] LGD is a supervisory parameter, fixed at 45% for senior unsecured corporate, sovereign, and bank exposures without eligible collateral or guarantees, reflecting an estimate of economic loss post-default after recoveries. Adjustments apply for secured exposures (e.g., reduced LGD for financial collateral via comprehensive method) or subordinated claims (75% LGD), but banks cannot use internal LGD models. This standardization curbs variability observed in bank-specific estimates, though critics note it may overstate or understate losses for certain portfolios compared to empirical recovery data.[23][1] EAD measures the expected gross exposure at default, incorporating on- and off-balance-sheet amounts. For on-balance-sheet items, EAD equals the outstanding amount; for off-balance-sheet commitments, it applies regulatory credit conversion factors (CCFs), such as 20% for short-term trade letters of credit or 50-100% for revocable/irrevocable commitments, rather than bank-derived CCFs. This supervisory overlay ensures consistency but limits adjustment for undrawn commitments' behavioral drawdown risks. Banks must estimate EAD for derivatives using current exposure method or internal models where approved, with add-ons for potential future exposure.[23][1] M, or effective maturity, defaults to 2.5 years for most exposures in Foundation IRB, simplifying calculations by assuming average loan duration without bank-specific modeling. For exposures with explicit maturities exceeding one year, M can be adjusted within bounds (e.g., 1-5 years), but supervisory formulas cap its impact to avoid excessive capital relief for long-term loans. This parameter influences risk weights modestly through maturity adjustment factors in the IRB formula, emphasizing PD and LGD dominance. Post-Basel II calibrations in Basel III introduced output floors (e.g., 72.5% of standardized approach) to address parameter conservatism.[23][11]Formulae for Risk-Weighted Assets

In the Foundation IRB approach, risk-weighted assets (RWA) for non-defaulted corporate, sovereign, and bank exposures are derived from the exposure at default (EAD) multiplied by a risk weight (RW), where RW equals the capital requirement K multiplied by 12.5, reflecting the reciprocal of the 8% minimum capital ratio. Banks estimate only the probability of default (PD), while supervisors prescribe LGD at 45% for senior unsecured claims (75% for subordinated claims without specific protection) and effective maturity M (defaulting to 2.5 years if not calculated precisely). This structure aims to balance internal risk assessment with standardized conservatism to mitigate model risk.[24][11] The capital requirement K is computed as:K = [LGD × N( (1 - R)^{-0.5} × G(PD) + (R / (1 - R))^{0.5} × G(0.999) ) - PD × LGD] × (1 - 1.5 × b(PD))^{-1} × (1 + (M - 2.5) × b(PD))

K = [LGD × N( (1 - R)^{-0.5} × G(PD) + (R / (1 - R))^{0.5} × G(0.999) ) - PD × LGD] × (1 - 1.5 × b(PD))^{-1} × (1 + (M - 2.5) × b(PD))

R = 0.12 × \frac{1 - e^{-50 × PD}}{1 - e^{-50}} + 0.24 × \left(1 - \frac{1 - e^{-50 × PD}}{1 - e^{-50}}\right)

R = 0.12 × \frac{1 - e^{-50 × PD}}{1 - e^{-50}} + 0.24 × \left(1 - \frac{1 - e^{-50 × PD}}{1 - e^{-50}}\right)

b(PD) = [0.11852 - 0.05478 × \ln(PD)]^2

b(PD) = [0.11852 - 0.05478 × \ln(PD)]^2