Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Survival analysis

View on WikipediaThis article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

Survival analysis is a branch of statistics for analyzing the expected duration of time until one event occurs, such as death in biological organisms and failure in mechanical systems.[1] This topic is called reliability theory, reliability analysis or reliability engineering in engineering, duration analysis or duration modelling in economics, and event history analysis in sociology. Survival analysis attempts to answer certain questions, such as what is the proportion of a population which will survive past a certain time? Of those that survive, at what rate will they die or fail? Can multiple causes of death or failure be taken into account? How do particular circumstances or characteristics increase or decrease the probability of survival?

To answer such questions, it is necessary to define "lifetime". In the case of biological survival, death is unambiguous, but for mechanical reliability, failure may not be well-defined, for there may well be mechanical systems in which failure is partial, a matter of degree, or not otherwise localized in time. Even in biological problems, some events (for example, heart attack or other organ failure) may have the same ambiguity. The theory outlined below assumes well-defined events at specific times; other cases may be better treated by models which explicitly account for ambiguous events.

More generally, survival analysis involves the modelling of time to event data; in this context, death or failure is considered an "event" in the survival analysis literature – traditionally only a single event occurs for each subject, after which the organism or mechanism is dead or broken[2]. Recurring event or repeated event models relax that assumption. The study of recurring events is relevant in systems reliability, and in many areas of social sciences and medical research.

Introduction to survival analysis

[edit]Survival analysis is used in several ways:

- To describe the survival times of members of a group

- To compare the survival times of two or more groups

- To describe the effect of categorical or quantitative variables on survival

- Cox proportional hazards regression

- Parametric survival models

- Survival trees

- Survival random forests

Definitions of common terms in survival analysis

[edit]The following terms are commonly used in survival analyses[3]:

- Event: Death, disease occurrence, disease recurrence, recovery, or other experience of interest

- Time: The time from the beginning of an observation period (such as surgery or beginning treatment) to (i) an event, or (ii) end of the study, or (iii) loss of contact or withdrawal from the study.

- Censoring / Censored observation: Censoring occurs when we have some information about individual survival time, but we do not know the survival time exactly. The subject is censored in the sense that nothing is observed or known about that subject after the time of censoring. A censored subject may or may not have an event after the end of observation time.

- Survival function S(t): The probability that a subject survives longer than time t.

Example: Acute myelogenous leukemia survival data

[edit]This example uses the Acute Myelogenous Leukemia survival data set "aml" from the "survival" package in R. The data set is from Miller (1997)[4] and the question is whether the standard course of chemotherapy should be extended ('maintained') for additional cycles.

The aml data set sorted by survival time is shown in the box.

| observation | time

(weeks) |

status | x |

|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 5 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 13 | 5 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 14 | 8 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 15 | 8 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 1 | 9 | 1 | Maintained |

| 16 | 12 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 2 | 13 | 1 | Maintained |

| 3 | 13 | 0 | Maintained |

| 17 | 16 | 0 | Nonmaintained |

| 4 | 18 | 1 | Maintained |

| 5 | 23 | 1 | Maintained |

| 18 | 23 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 19 | 27 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 6 | 28 | 0 | Maintained |

| 20 | 30 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 7 | 31 | 1 | Maintained |

| 21 | 33 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 8 | 34 | 1 | Maintained |

| 22 | 43 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 9 | 45 | 0 | Maintained |

| 23 | 45 | 1 | Nonmaintained |

| 10 | 48 | 1 | Maintained |

| 11 | 161 | 0 | Maintained |

- Time is indicated by the variable "time", which is the survival or censoring time

- Event (recurrence of aml cancer) is indicated by the variable "status". 0 = no event (censored), 1 = event (recurrence)

- Treatment group: the variable "x" indicates if maintenance chemotherapy was given

The last observation (11), at 161 weeks, is censored. Censoring indicates that the patient did not have an event (no recurrence of aml cancer). Another subject, observation 3, was censored at 13 weeks (indicated by status=0). This subject was in the study for only 13 weeks, and the aml cancer did not recur during those 13 weeks. It is possible that this patient was enrolled near the end of the study, so that they could be observed for only 13 weeks. It is also possible that the patient was enrolled early in the study, but was lost to follow up or withdrew from the study. The table shows that other subjects were censored at 16, 28, and 45 weeks (observations 17, 6, and 9 with status=0). The remaining subjects all experienced events (recurrence of aml cancer) while in the study. The question of interest is whether recurrence occurs later in maintained patients than in non-maintained patients.

Kaplan–Meier plot for the aml data

[edit]The survival function S(t), is the probability that a subject survives longer than time t. S(t) is theoretically a smooth curve, but it is usually estimated using the Kaplan–Meier (KM) curve[5]. The graph shows the KM plot for the aml data and can be interpreted as follows:

- The x axis is time, from zero (when observation began) to the last observed time point.

- The y axis is the proportion of subjects surviving. At time zero, 100% of the subjects are alive without an event.

- The solid line (similar to a staircase) shows the progression of event occurrences.

- A vertical drop indicates an event. In the aml table shown above, two subjects had events at five weeks, two had events at eight weeks, one had an event at nine weeks, and so on. These events at five weeks, eight weeks and so on are indicated by the vertical drops in the KM plot at those time points.

- At the far right end of the KM plot there is a tick mark at 161 weeks. The vertical tick mark indicates that a patient was censored at this time. In the aml data table five subjects were censored, at 13, 16, 28, 45 and 161 weeks. There are five tick marks in the KM plot, corresponding to these censored observations.

Life table for the aml data

[edit]A life table summarizes survival data in terms of the number of events and the proportion surviving at each event time point. The life table for the aml data, created using the R software, is shown.

| time | n.risk | n.event | survival | std.err | lower 95% CI | upper 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 23 | 2 | 0.913 | 0.0588 | 0.8049 | 1 |

| 8 | 21 | 2 | 0.8261 | 0.079 | 0.6848 | 0.996 |

| 9 | 19 | 1 | 0.7826 | 0.086 | 0.631 | 0.971 |

| 12 | 18 | 1 | 0.7391 | 0.0916 | 0.5798 | 0.942 |

| 13 | 17 | 1 | 0.6957 | 0.0959 | 0.5309 | 0.912 |

| 18 | 14 | 1 | 0.646 | 0.1011 | 0.4753 | 0.878 |

| 23 | 13 | 2 | 0.5466 | 0.1073 | 0.3721 | 0.803 |

| 27 | 11 | 1 | 0.4969 | 0.1084 | 0.324 | 0.762 |

| 30 | 9 | 1 | 0.4417 | 0.1095 | 0.2717 | 0.718 |

| 31 | 8 | 1 | 0.3865 | 0.1089 | 0.2225 | 0.671 |

| 33 | 7 | 1 | 0.3313 | 0.1064 | 0.1765 | 0.622 |

| 34 | 6 | 1 | 0.2761 | 0.102 | 0.1338 | 0.569 |

| 43 | 5 | 1 | 0.2208 | 0.0954 | 0.0947 | 0.515 |

| 45 | 4 | 1 | 0.1656 | 0.086 | 0.0598 | 0.458 |

| 48 | 2 | 1 | 0.0828 | 0.0727 | 0.0148 | 0.462 |

The life table summarizes the events and the proportion surviving at each event time point. The columns in the life table have the following interpretation:

- time gives the time points at which events occur.

- n.risk is the number of subjects at risk immediately before the time point, t. Being "at risk" means that the subject has not had an event before time t, and is not censored before or at time t.

- n.event is the number of subjects who have events at time t.

- survival is the proportion surviving, as determined using the Kaplan–Meier product-limit estimate.

- std.err is the standard error of the estimated survival. The standard error of the Kaplan–Meier product-limit estimate it is calculated using Greenwood's formula, and depends on the number at risk (n.risk in the table), the number of deaths (n.event in the table) and the proportion surviving (survival in the table).

- lower 95% CI and upper 95% CI are the lower and upper 95% confidence bounds for the proportion surviving.

Log-rank test: Testing for differences in survival in the aml data

[edit]The log-rank test compares the survival times of two or more groups[6]. This example uses a log-rank test for a difference in survival in the maintained versus non-maintained treatment groups in the aml data. The graph shows KM plots for the aml data broken out by treatment group, which is indicated by the variable "x" in the data.

The null hypothesis for a log-rank test is that the groups have the same survival. The expected number of subjects surviving at each time point in each is adjusted for the number of subjects at risk in the groups at each event time. The log-rank test determines if the observed number of events in each group is significantly different from the expected number[7]. The formal test is based on a chi-squared statistic. When the log-rank statistic is large, it is evidence for a difference in the survival times between the groups. The log-rank statistic approximately has a Chi-squared distribution with one degree of freedom, and the p-value is calculated using the Chi-squared test.

For the example data, the log-rank test for difference in survival gives a p-value of p=0.0653, indicating that the treatment groups do not differ significantly in survival, assuming an alpha level of 0.05. The sample size of 23 subjects is modest, so there is little power to detect differences between the treatment groups. The chi-squared test is based on asymptotic approximation, so the p-value should be regarded with caution for small sample sizes[8].

Cox proportional hazards (PH) regression analysis

[edit]Kaplan–Meier curves and log-rank tests are most useful when the predictor variable is categorical (e.g., drug vs. placebo), or takes a small number of values (e.g., drug doses 0, 20, 50, and 100 mg/day) that can be treated as categorical[9]. The log-rank test and KM curves don't work easily with quantitative predictors such as gene expression, white blood count, or age. For quantitative predictor variables, an alternative method is Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Cox PH models work also with categorical predictor variables, which are encoded as {0,1} indicator or dummy variables. The log-rank test is a special case of a Cox PH analysis, and can be performed using Cox PH software.

Example: Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for melanoma

[edit]This example uses the melanoma data set from Dalgaard Chapter 14. [10]

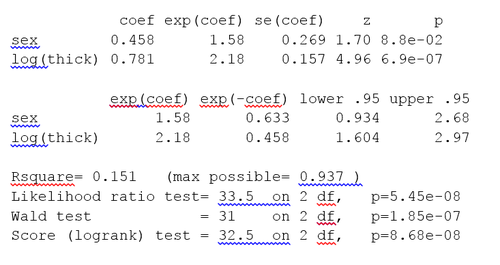

Data are in the R package ISwR. The Cox proportional hazards regression using R gives the results shown in the box.

The Cox regression results are interpreted as follows.

- Sex is encoded as a numeric vector (1: female, 2: male). The R summary for the Cox model gives the hazard ratio (HR) for the second group relative to the first group, that is, male versus female.

- coef = 0.662 is the estimated logarithm of the hazard ratio for males versus females.

- exp(coef) = 1.94 = exp(0.662) - The log of the hazard ratio (coef= 0.662) is transformed to the hazard ratio using exp(coef). The summary for the Cox model gives the hazard ratio for the second group relative to the first group, that is, male versus female. The estimated hazard ratio of 1.94 indicates that males have higher risk of death (lower survival rates) than females, in these data.

- se(coef) = 0.265 is the standard error of the log hazard ratio.

- z = 2.5 = coef/se(coef) = 0.662/0.265. Dividing the coef by its standard error gives the z score.

- p=0.013. The p-value corresponding to z=2.5 for sex is p=0.013, indicating that there is a significant difference in survival as a function of sex.

The summary output also gives upper and lower 95% confidence intervals for the hazard ratio: lower 95% bound = 1.15; upper 95% bound = 3.26.

Finally, the output gives p-values for three alternative tests for overall significance of the model:

- Likelihood ratio test = 6.15 on 1 df, p=0.0131

- Wald test = 6.24 on 1 df, p=0.0125

- Score (log-rank) test = 6.47 on 1 df, p=0.0110

These three tests are asymptotically equivalent. For large enough N, they will give similar results. For small N, they may differ somewhat. The last row, "Score (logrank) test" is the result for the log-rank test, with p=0.011, the same result as the log-rank test, because the log-rank test is a special case of a Cox PH regression. The Likelihood ratio test has better behavior for small sample sizes, so it is generally preferred.

Cox model using a covariate in the melanoma data

[edit]The Cox model extends the log-rank test by allowing the inclusion of additional covariates.[11] This example use the melanoma data set where the predictor variables include a continuous covariate, the thickness of the tumor (variable name = "thick").

In the histograms, the thickness values are positively skewed and do not have a Gaussian-like, Symmetric probability distribution. Regression models, including the Cox model, generally give more reliable results with normally-distributed variables.[citation needed] For this example we may use a logarithmic transform. The log of the thickness of the tumor looks to be more normally distributed, so the Cox models will use log thickness. The Cox PH analysis gives the results in the box.

The p-value for all three overall tests (likelihood, Wald, and score) are significant, indicating that the model is significant. The p-value for log(thick) is 6.9e-07, with a hazard ratio HR = exp(coef) = 2.18, indicating a strong relationship between the thickness of the tumor and increased risk of death.

By contrast, the p-value for sex is now p=0.088. The hazard ratio HR = exp(coef) = 1.58, with a 95% confidence interval of 0.934 to 2.68. Because the confidence interval for HR includes 1, these results indicate that sex makes a smaller contribution to the difference in the HR after controlling for the thickness of the tumor, and only trend toward significance. Examination of graphs of log(thickness) by sex and a t-test of log(thickness) by sex both indicate that there is a significant difference between men and women in the thickness of the tumor when they first see the clinician.

The Cox model assumes that the hazards are proportional. The proportional hazard assumption may be tested using the R function cox.zph(). A p-value which is less than 0.05 indicates that the hazards are not proportional. For the melanoma data we obtain p=0.222. Hence, we cannot reject the null hypothesis of the hazards being proportional. Additional tests and graphs for examining a Cox model are described in the textbooks cited.

Extensions to Cox models

[edit]Cox models can be extended to deal with variations on the simple analysis.

- Stratification. The subjects can be divided into strata, where subjects within a stratum are expected to be relatively more similar to each other than to randomly chosen subjects from other strata. The regression parameters are assumed to be the same across the strata, but a different baseline hazard may exist for each stratum. Stratification is useful for analyses using matched subjects, for dealing with patient subsets, such as different clinics, and for dealing with violations of the proportional hazard assumption.

- Time-varying covariates. Some variables, such as gender and treatment group, generally stay the same in a clinical trial. Other clinical variables, such as serum protein levels or dose of concomitant medications may change over the course of a study. Cox models may be extended for such time-varying covariates.

Tree-structured survival models

[edit]The Cox PH regression model is a linear model. It is similar to linear regression and logistic regression. Specifically, these methods assume that a single line, curve, plane, or surface is sufficient to separate groups (alive, dead) or to estimate a quantitative response (survival time).

In some cases alternative partitions give more accurate classification or quantitative estimates. One set of alternative methods are tree-structured survival models,[12][13][14] including survival random forests.[15] Tree-structured survival models may give more accurate predictions than Cox models. Examining both types of models for a given data set is a reasonable strategy.

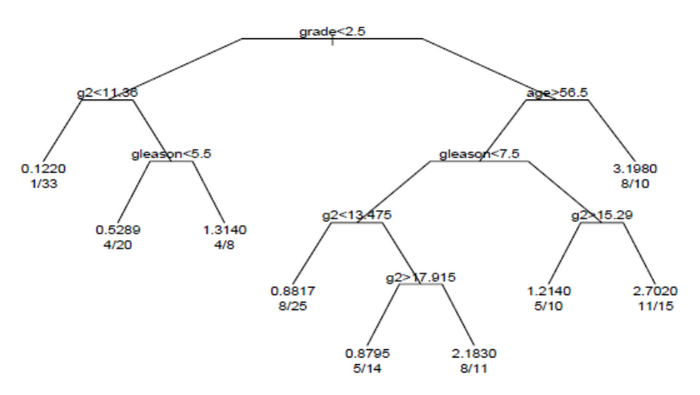

Example survival tree analysis

[edit]This example of a survival tree analysis uses the R package "rpart".[16] The example is based on 146 stage C prostate cancer patients in the data set stagec in rpart. Rpart and the stagec example are described in Atkinson and Therneau (1997),[17] which is also distributed as a vignette of the rpart package.[16]

The variables in stages are:

- pgtime: time to progression, or last follow-up free of progression

- pgstat: status at last follow-up (1=progressed, 0=censored)

- age: age at diagnosis

- eet: early endocrine therapy (1=no, 0=yes)

- ploidy: diploid/tetraploid/aneuploid DNA pattern

- g2: % of cells in G2 phase

- grade: tumor grade (1-4)

- gleason: Gleason grade (3-10)

The survival tree produced by the analysis is shown in the figure.

Each branch in the tree indicates a split on the value of a variable. For example, the root of the tree splits subjects with grade < 2.5 versus subjects with grade 2.5 or greater. The terminal nodes indicate the number of subjects in the node, the number of subjects who have events, and the relative event rate compared to the root. In the node on the far left, the values 1/33 indicate that one of the 33 subjects in the node had an event, and that the relative event rate is 0.122. In the node on the far right bottom, the values 11/15 indicate that 11 of 15 subjects in the node had an event, and the relative event rate is 2.7.

Survival random forests

[edit]An alternative to building a single survival tree is to build many survival trees, where each tree is constructed using a sample of the data, and average the trees to predict survival.[15] This is the method underlying the survival random forest models. Survival random forest analysis is available in the R package "randomForestSRC".[18]

The randomForestSRC package includes an example survival random forest analysis using the data set pbc. This data is from the Mayo Clinic Primary Biliary Cirrhosis (PBC) trial of the liver conducted between 1974 and 1984. In the example, the random forest survival model gives more accurate predictions of survival than the Cox PH model. The prediction errors are estimated by bootstrap re-sampling.

Deep Learning survival models

[edit]Recent advancements in deep representation learning have been extended to survival estimation. The DeepSurv[19] model proposes to replace the log-linear parameterization of the CoxPH model with a multi-layer perceptron. Further extensions like Deep Survival Machines[20] and Deep Cox Mixtures[21] involve the use of latent variable mixture models to model the time-to-event distribution as a mixture of parametric or semi-parametric distributions while jointly learning representations of the input covariates. Deep learning approaches have shown superior performance especially on complex input data modalities such as images and clinical time-series.

General formulation

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2025) |

Survival function

[edit]The object of primary interest is the survival function, conventionally denoted S, which is defined as where t is some time, T is a random variable denoting the time of death, or more generally any event, and "Pr" stands for probability. That is, the survival function is the probability of observing an event time greater than some specified time t.[7] The survival function is also called the survivor function or survivorship function in problems of biological survival, and the reliability function in mechanical survival problems[22]. In the latter case, the reliability function is denoted R(t).

Usually one assumes S(0) = 1, although it could be less than 1 if there is the possibility of immediate death or failure.

The survival function must be non-increasing: S(u) ≤ S(t) if u ≥ t. This property follows directly because T>u implies T>t. This reflects the notion that survival to a later age is possible only if all younger ages are attained. Given this property, the lifetime distribution function and event density (F and f below) are well-defined[2].

The survival function is usually assumed to approach zero as age increases without bound (i.e., S(t) → 0 as t → ∞), although the limit could be greater than zero if eternal life is possible. For instance, we could apply survival analysis to a mixture of stable and unstable carbon isotopes; unstable isotopes would decay sooner or later, but the stable isotopes would last indefinitely.

Lifetime distribution function and event density

[edit]Related quantities are defined in terms of the survival function.

The lifetime distribution function, conventionally denoted F, is defined as the complement of the survival function,

If F is differentiable then the derivative, which is the density function of the lifetime distribution, is conventionally denoted f,

The function f is sometimes called the event density; it is the rate of death or failure events per unit time.

The survival function can be expressed in terms of probability distribution and probability density functions

Similarly, a survival event density function can be defined as

In other fields, such as statistical physics, the survival event density function is known as the first passage time density.

Hazard function and cumulative hazard function

[edit]The hazard function is defined as the event rate at time conditional on survival at time

Synonyms for hazard function in different fields include hazard rate, intensity function[23], force of mortality (demography and actuarial science, denoted by ), force of failure, or failure rate (engineering, denoted ). For example, in actuarial science, denotes rate of death for people aged , whereas in reliability engineering denotes rate of failure of components after operation for time .

The hazard function represents the probability that a subject will experience an event in the next small interval of time, divided by the length of this interval, given that they have survived up to time [23]. Formally, this can be written as follows:

where Bayes' theorem, and identifying as the survival function, has been used in the first equality, and the definition of the density function of the lifetime distribution in the second.

Any function is a hazard function if and only if it satisfies the following properties:

- ,

- .

In fact, the hazard rate is usually more informative about the underlying mechanism of failure than the other representations of a lifetime distribution.

The hazard function must be non-negative, , and its integral over must be infinite, but is not otherwise constrained; it may be increasing or decreasing, non-monotonic, or discontinuous. An example is the bathtub curve hazard function, which is large for small values of , decreasing to some minimum, and thereafter increasing again; this can model the property of some mechanical systems to either fail soon after operation, or much later, as the system ages.

The hazard function can alternatively be represented in terms of the cumulative hazard function, conventionally denoted or :

so transposing signs and exponentiating

or differentiating (with the chain rule)

The name "cumulative hazard function" is derived from the fact that

which is the "accumulation" of the hazard over time.

From the definition of , we see that it increases without bound as t tends to infinity (assuming that tends to zero). This implies that must not decrease too quickly, since, by definition, the cumulative hazard has to diverge. For example, is not the hazard function of any survival distribution, because its integral converges to 1.

The survival function , the cumulative hazard function , the density , the hazard function , and the lifetime distribution function are related through

Quantities derived from the survival distribution

[edit]Future lifetime at a given time is the time remaining until death, given survival to age . Thus, it is in the present notation. The expected future lifetime is the expected value of future lifetime. The probability of death at or before age , given survival until age , is just

Therefore, the probability density of future lifetime is

and the expected future lifetime is

where the second expression is obtained using integration by parts.

For , that is, at birth, this reduces to the expected lifetime.

In reliability problems, the expected lifetime is called the mean time to failure, and the expected future lifetime is called the mean residual lifetime.

As the probability of an individual surviving until age t or later is S(t), by definition, the expected number of survivors at age t out of an initial population of n newborns is n × S(t), assuming the same survival function for all individuals. Thus the expected proportion of survivors is S(t). If the survival of different individuals is independent, the number of survivors at age t has a binomial distribution with parameters n and S(t), and the variance of the proportion of survivors is S(t) × (1-S(t))/n.

The age at which a specified proportion of survivors remain can be found by solving the equation S(t) = q for t, where q is the quantile in question. Typically one is interested in the median lifetime, for which q = 1/2, or other quantiles such as q = 0.90 or q = 0.99.

Censoring

[edit]Censoring is a form of missing data problem in which time to event is not observed for reasons such as termination of study before all recruited subjects have shown the event of interest or the subject has left the study prior to experiencing an event. Censoring is common in survival analysis.

If only the lower limit l for the true event time T is known such that T > l, this is called right censoring. Right censoring will occur, for example, for those subjects whose birth date is known but who are still alive when they are lost to follow-up or when the study ends. We generally encounter right-censored data.

If the event of interest has already happened before the subject is included in the study but it is not known when it occurred, the data is said to be left-censored.[24] When it can only be said that the event happened between two observations or examinations, this is interval censoring.

Left censoring occurs for example when a permanent tooth has already emerged prior to the start of a dental study that aims to estimate its emergence distribution. In the same study, an emergence time is interval-censored when the permanent tooth is present in the mouth at the current examination but not yet at the previous examination. Interval censoring often occurs in HIV/AIDS studies. Indeed, time to HIV seroconversion can be determined only by a laboratory assessment which is usually initiated after a visit to the physician. Then one can only conclude that HIV seroconversion has happened between two examinations. The same is true for the diagnosis of AIDS, which is based on clinical symptoms and needs to be confirmed by a medical examination.

It may also happen that subjects with a lifetime less than some threshold may not be observed at all: this is called truncation. Note that truncation is different from left censoring, since for a left censored datum, we know the subject exists, but for a truncated datum, we may be completely unaware of the subject. Truncation is also common. In a so-called delayed entry study, subjects are not observed at all until they have reached a certain age. For example, people may not be observed until they have reached the age to enter school. Any deceased subjects in the pre-school age group would be unknown. Left-truncated data are common in actuarial work for life insurance and pensions.[25]

Left-censored data can occur when a person's survival time becomes incomplete on the left side of the follow-up period for the person. For example, in an epidemiological example, we may monitor a patient for an infectious disorder starting from the time when he or she is tested positive for the infection. Although we may know the right-hand side of the duration of interest, we may never know the exact time of exposure to the infectious agent.[26]

Fitting parameters to data

[edit]Survival models can be usefully viewed as ordinary regression models in which the response variable is time. However, computing the likelihood function (needed for fitting parameters or making other kinds of inferences) is complicated by the censoring. The likelihood function for a survival model, in the presence of censored data, is formulated as follows. By definition the likelihood function is the conditional probability of the data given the parameters of the model. It is customary to assume that the data are independent given the parameters. Then the likelihood function is the product of the likelihood of each datum. It is convenient to partition the data into four categories: uncensored, left censored, right censored, and interval censored. These are denoted "unc.", "l.c.", "r.c.", and "i.c." in the equation below.

For uncensored data, with equal to the age at death, we have

For left-censored data, such that the age at death is known to be less than , we have

For right-censored data, such that the age at death is known to be greater than , we have

For an interval censored datum, such that the age at death is known to be less than and greater than , we have

An important application where interval-censored data arises is current status data, where an event is known not to have occurred before an observation time and to have occurred before the next observation time.

Non-parametric estimation

[edit]The Kaplan–Meier estimator can be used to estimate the survival function. The Nelson–Aalen estimator can be used to provide a non-parametric estimate of the cumulative hazard rate function. These estimators require lifetime data. Periodic case (cohort) and death (and recovery) counts are statistically sufficient to make nonparametric maximum likelihood and least squares estimates of survival functions, without lifetime data.

Discrete-time survival models

[edit]While many parametric models assume a continuous-time, discrete-time survival models can be mapped to a binary classification problem. In a discrete-time survival model the survival period is artificially resampled in intervals where for each interval a binary target indicator is recorded if the event takes place in a certain time horizon.[27] If a binary classifier (potentially enhanced with a different likelihood to take more structure of the problem into account) is calibrated, then the classifier score is the hazard function (i.e. the conditional probability of failure).[27]

Discrete-time survival models are connected to empirical likelihood.[28][29]

Goodness of fit

[edit]The goodness of fit of survival models can be assessed using scoring rules.[30]

Cure model

[edit]A cure model allows for the possibility that some individuals never experience the event of interest. This creates survival curves that plateau rather than always converging to zero.

A cure model has two linked components

1. Logistic regression for the probability of never experiencing the event:

2. Hazard model E.g. discrete time logistic regression for the conditional event hazard at time t, given susceptibility:

So the combined survival function is

First term: cured individuals, who survive indefinitely.

Second term: susceptible individuals, whose survival declines according to the hazard.

Without a cure model, survival is forced to zero in the limit of large times. With a cure fraction, survival instead converges to

Computer software for survival analysis

[edit]The textbook by Kleinbaum has examples of survival analyses using SAS, R, and other packages.[6] The textbooks by Brostrom,[31] Dalgaard[10] and Tableman and Kim[32] give examples of survival analyses using R (or using S, and which run in R).

Distributions used in survival analysis

[edit]Applications

[edit]- Credit risk[33][34]

- False conviction rate of inmates sentenced to death[35]

- Lead times for metallic components in the aerospace industry[36]

- Predictors of criminal recidivism[37]

- Survival distribution of radio-tagged animals[38]

- Time-to-violent death of Roman emperors[39]

- Intertrade waiting times of electronically traded shares on a stock exchange[40]

See also

[edit]- Accelerated failure time model

- Bayesian survival analysis

- Cell survival curve

- Censoring (statistics)

- Chance-constrained portfolio selection

- Failure rate

- Frequency of exceedance

- Kaplan–Meier estimator

- Logrank test

- Maximum likelihood

- Mortality rate

- MTBF

- Proportional hazards models

- Reliability theory

- Residence time (statistics)

- Sequence analysis in social sciences

- Survival function

- Survival rate

- Discrete-time proportional hazards

References

[edit]- ^ Clark, T G; Bradburn, M J; Love, S B; Altman, D G (2003-07-15). "Survival Analysis Part I: Basic concepts and first analyses". British Journal of Cancer. 89 (2): 232–238. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601118. PMC 2394262. PMID 12865907.

- ^ a b Kalbfleisch, John D.; Prentice, Ross L. (2002-08-26). The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics (1 ed.). Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118032985. ISBN 978-0-471-36357-6.

- ^ Mills, Melinda (2011). Introducing survival and event history analysis. London Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage. ISBN 978-1-84860-101-7.

- ^ Miller, Rupert G. (1997), Survival analysis, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 0-471-25218-2

- ^ Kaplan, E. L.; Meier, Paul (1958-06-01). "Nonparametric Estimation from Incomplete Observations". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 53 (282): 457–481. doi:10.1080/01621459.1958.10501452. ISSN 0162-1459.

- ^ a b Kleinbaum, David G.; Klein, Mitchel (2012), Survival analysis: A Self-learning text (Third ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-1-4419-6645-2

- ^ a b Hosmer, David W.; Lemeshow, Stanley; May, Susanne (2008-02-26). Applied Survival Analysis. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9780470258019. ISBN 978-0-471-75499-2.

- ^ Agresti, Alan (2018). Statistical methods for the social sciences (Fifth edition, global ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education, Limited. ISBN 978-1-292-22034-5.

- ^ Therneau, Terry M.; Grambsch, Patricia M. (2000). Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. Statistics for biology and health. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-98784-2.

- ^ a b Dalgaard, Peter (2008), Introductory Statistics with R (Second ed.), Springer, ISBN 978-0-387-79053-4

- ^ Saegusa, Takumi; Di, Chongzhi; Chen, Ying Qing (September 2014). "Hypothesis testing for an extended cox model with time-varying coefficients". Biometrics. 70 (3): 619–628. doi:10.1111/biom.12185. ISSN 0006-341X. PMC 4247822. PMID 24888739.

- ^ Segal, Mark Robert (1988). "Regression Trees for Censored Data". Biometrics. 44 (1): 35–47. doi:10.2307/2531894. JSTOR 2531894. S2CID 60974957.

- ^ Leblanc, Michael; Crowley, John (1993). "Survival Trees by Goodness of Split". Journal of the American Statistical Association. 88 (422): 457–467. doi:10.1080/01621459.1993.10476296. ISSN 0162-1459.

- ^ Ritschard, Gilbert; Gabadinho, Alexis; Muller, Nicolas S.; Studer, Matthias (2008). "Mining event histories: a social science perspective". International Journal of Data Mining, Modelling and Management. 1 (1): 68. doi:10.1504/IJDMMM.2008.022538. ISSN 1759-1163.

- ^ a b Ishwaran, Hemant; Kogalur, Udaya B.; Blackstone, Eugene H.; Lauer, Michael S. (2008-09-01). "Random survival forests". The Annals of Applied Statistics. 2 (3). arXiv:0811.1645. doi:10.1214/08-AOAS169. ISSN 1932-6157. S2CID 2003897.

- ^ a b Therneau, Terry J.; Atkinson, Elizabeth J. "rpart: Recursive Partitioning and Regression Trees". CRAN. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ Atkinson, Elizabeth J.; Therneau, Terry J. (1997). An introduction to recursive partitioning using the RPART routines. Mayo Foundation.

- ^ Ishwaran, Hemant; Kogalur, Udaya B. "randomForestSRC: Fast Unified Random Forests for Survival, Regression, and Classification (RF-SRC)". CRAN. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ Singh, Jared; Katzman, L. (2018). "DeepSurv: personalized treatment recommender system using a Cox proportional hazards deep neural network". BMC Medical Research Methodology.

- ^ Nagpal, Chirag (2021). "Deep survival machines: Fully parametric survival regression and representation learning for censored data with competing risks". IEEE Journal of Biomedical and Health Informatics. 25 (8): 3163–3175. arXiv:2003.01176. Bibcode:2021IJBHI..25.3163N. doi:10.1109/JBHI.2021.3052441. PMID 33460387. S2CID 211817982.

- ^ Nagpal, Chirag (2021). "Deep Cox mixtures for survival regression". Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference. arXiv:2101.06536.

- ^ Meeker, William Q.; Escobar, Luis A.; Pascual, Francis G. (2022). Statistical methods for reliability data. Wiley series in probability and statistics (Second ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-59448-3.

- ^ a b Moore, Dirk F. (2016), "Basic Principles of Survival Analysis", Applied Survival Analysis Using R, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 11–24, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-31245-3_2, ISBN 978-3-319-31243-9, retrieved 2025-10-29

- ^ Darity, William A. Jr., ed. (2008). "Censoring, Left and Right". International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Macmillan. pp. 473–474. Retrieved 6 November 2016.

- ^ Richards, S. J. (2012). "A handbook of parametric survival models for actuarial use". Scandinavian Actuarial Journal. 2012 (4): 233–257. doi:10.1080/03461238.2010.506688. S2CID 119577304.

- ^ Singh, R.; Mukhopadhyay, K. (2011). "Survival analysis in clinical trials: Basics and must know areas". Perspect Clin Res. 2 (4): 145–148. doi:10.4103/2229-3485.86872. PMC 3227332. PMID 22145125.

- ^ a b Suresh, K., Severn, C. & Ghosh, D. Survival prediction models: an introduction to discrete-time modeling. BMC Med Res Methodol 22, 207 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-022-01679-6 , https://bmcmedresmethodol.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12874-022-01679-6

- ^ Empirical Likelihood in Survival Analysis, Gang Li (U.S.A.), Runze Li (U.S.A.), and Mai Zhou (U.S.A.), Contemporary Multivariate Analysis and Design of Experiments. March 2005, 337-349, https://www.ms.uky.edu/~mai/research/llz.pdf

- ^ The Empirical Distribution Function with Arbitrarily Grouped, Censored and Truncated Data, Bruce W. Turnbull, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) Vol. 38, No. 3 (1976), pp. 290-295 (6 pages), https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA030940.pdf

- ^ Proper Scoring Rules for Survival Analysis, Hiroki Yanagisawa, https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.00621v3

- ^ Brostrom, Göran (2012), Event History Analysis with R (First ed.), Chapman & Hall/CRC, ISBN 978-1-4398-3164-9

- ^ Tableman, Mara; Kim, Jong Sung (2003), Survival Analysis Using S (First ed.), Chapman and Hall/CRC, ISBN 978-1-58488-408-8

- ^ Stepanova, Maria; Thomas, Lyn (2002-04-01). "Survival Analysis Methods for Personal Loan Data". Operations Research. 50 (2): 277–289. doi:10.1287/opre.50.2.277.426. ISSN 0030-364X.

- ^ Glennon, Dennis; Nigro, Peter (2005). "Measuring the Default Risk of Small Business Loans: A Survival Analysis Approach". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking. 37 (5): 923–947. doi:10.1353/mcb.2005.0051. ISSN 0022-2879. JSTOR 3839153. S2CID 154615623.

- ^ Kennedy, Edward H.; Hu, Chen; O'Brien, Barbara; Gross, Samuel R. (2014-05-20). "Rate of false conviction of criminal defendants who are sentenced to death". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (20): 7230–7235. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.7230G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1306417111. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 4034186. PMID 24778209.

- ^ de Cos Juez, F. J.; García Nieto, P. J.; Martínez Torres, J.; Taboada Castro, J. (2010-10-01). "Analysis of lead times of metallic components in the aerospace industry through a supported vector machine model". Mathematical and Computer Modelling. Mathematical Models in Medicine, Business & Engineering 2009. 52 (7): 1177–1184. doi:10.1016/j.mcm.2010.03.017. hdl:10651/8288. ISSN 0895-7177.

- ^ Spivak, Andrew L.; Damphousse, Kelly R. (2006). "Who Returns to Prison? A Survival Analysis of Recidivism among Adult Offenders Released in Oklahoma, 1985 – 2004". Justice Research and Policy. 8 (2): 57–88. doi:10.3818/jrp.8.2.2006.57. ISSN 1525-1071. S2CID 144566819.

- ^ Pollock, Kenneth H.; Winterstein, Scott R.; Bunck, Christine M.; Curtis, Paul D. (1989). "Survival Analysis in Telemetry Studies: The Staggered Entry Design". The Journal of Wildlife Management. 53 (1): 7–15. doi:10.2307/3801296. ISSN 0022-541X. JSTOR 3801296.

- ^ Saleh, Joseph Homer (2019-12-23). "Statistical reliability analysis for a most dangerous occupation: Roman emperor". Palgrave Communications. 5 (1) 155: 1–7. doi:10.1057/s41599-019-0366-y. ISSN 2055-1045.

- ^ Kreer, Markus; Kizilersu, Ayse; Thomas, Anthony W. (2022). "Censored expectation maximization algorithm for mixtures: Application to intertrade waiting times". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications. 587 (1) 126456. Bibcode:2022PhyA..58726456K. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2021.126456. ISSN 0378-4371. S2CID 244198364.

Further reading

[edit]- Collett, David (2003). Modelling Survival Data in Medical Research (Second ed.). Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. ISBN 1-58488-325-1.

- Elandt-Johnson, Regina; Johnson, Norman (1999). Survival Models and Data Analysis. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-34992-5.

- Kalbfleisch, J. D.; Prentice, Ross L. (2002). The statistical analysis of failure time data. New York: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-36357-X.

- Lawless, Jerald F. (2003). Statistical Models and Methods for Lifetime Data (2nd ed.). Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0-471-37215-3.

- Rausand, M.; Hoyland, A. (2004). System Reliability Theory: Models, Statistical Methods, and Applications. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-47133-X.

External links

[edit]- Therneau, Terry. "A Package for Survival Analysis in S". Archived from the original on 2006-09-07. via Dr. Therneau's page on the Mayo Clinic website

- "Engineering Statistics Handbook". NIST/SEMATEK.

- SOCR, Survival analysis applet and interactive learning activity.

- Survival/Failure Time Analysis @ Statistics' Textbook Page

- Survival Analysis in R

- Lifelines, a Python package for survival analysis

- Survival Analysis in NAG Fortran Library

Survival analysis

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Overview and Importance

Survival analysis is a branch of statistics focused on the study of time until the occurrence of a specified event, such as death, failure, or recovery, where the data often include incomplete observations known as censoring.[1] This approach enables researchers to model and infer the distribution of these times-to-event while accounting for the fact that not all subjects may experience the event within the observation period.[4] The importance of survival analysis lies in its ability to handle real-world scenarios where events do not occur uniformly or completely within the study timeframe, making it indispensable across diverse disciplines. In medicine, it is widely applied to evaluate patient survival times following treatments or diagnoses, such as assessing outcomes in clinical trials for chronic diseases.[5] In engineering, it supports reliability engineering by analyzing component failure times to improve design and maintenance strategies.[6] Similarly, in economics, it examines durations like time to unemployment or bankruptcy to inform policy and risk assessment.[5] Standard statistical methods, such as calculating means or proportions, often fail with time-to-event data because they cannot properly incorporate censored observations, leading to biased estimates that underestimate true event times.[7] For instance, in a study tracking time to remission among cancer patients, some individuals may still be in remission at the study's end or drop out early, providing only partial information; ignoring this censoring would discard valuable data and distort survival probabilities.[8]Historical Development

The roots of survival analysis trace back to 17th-century actuarial science, where early efforts focused on quantifying mortality patterns through life tables. In 1662, John Graunt published Natural and Political Observations Made upon the Bills of Mortality, presenting the first known life table derived from empirical data on births and deaths in London parishes, which estimated survival probabilities across age groups and laid foundational principles for demographic analysis. This work marked a shift from anecdotal observations to systematic data-driven mortality assessment, influencing subsequent actuarial practices.[9] Building on Graunt's innovations, Edmund Halley refined life table methodology in 1693 with his analysis of birth and death records from Breslau (now Wrocław), Poland, producing one of the earliest complete life tables that estimated the number of survivors from a birth cohort to various ages and incorporated uncertainty in population estimates.[10] Halley's table, published in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, enabled practical applications such as annuity pricing and highlighted the variability in survival rates, prompting later refinements in the 18th and 19th centuries by demographers like Abraham de Moivre and Benjamin Gompertz, who introduced parametric models for mortality trends.[11] The 20th century saw survival analysis evolve into a rigorous statistical discipline, addressing censored data and estimation challenges. In 1926, Major Greenwood developed a variance estimator for life table survival probabilities, providing a method to quantify uncertainty in actuarial estimates and becoming a cornerstone for non-parametric inference.[12] This was extended in 1958 by Edward L. Kaplan and Paul Meier, who introduced the Kaplan-Meier estimator, a non-parametric product-limit method for estimating the survival function from incomplete observations, widely adopted in medical and reliability studies.[13] Edmund Gehan further advanced comparative techniques in 1965 with a generalized Wilcoxon test for singly censored samples, enabling robust hypothesis testing between survival distributions. A pivotal milestone occurred in 1972 when David Cox proposed the proportional hazards model, a semi-parametric regression framework that relates covariates to the hazard function without specifying its baseline form, revolutionizing the analysis of survival data in clinical trials and epidemiology.[14] Post-2000 developments expanded survival analysis through Bayesian approaches, which incorporate prior knowledge for flexible inference in complex models, and machine learning integrations after 2010, including neural networks for high-dimensional survival prediction that handle non-linear effects and large datasets more effectively than traditional methods.[15] In the 2020s, the field has shifted toward computational methods, leveraging deep learning and parallel processing to scale analyses for big data in biomedical applications, enhancing predictive accuracy and interpretability.[16]Core Concepts

Survival Function and Related Distributions

In survival analysis, the survival function, denoted , represents the probability that a random variable , which denotes the time until the occurrence of an event of interest, exceeds a given time . Thus, .[17] This function is non-increasing and right-continuous, with and under typical assumptions for positive survival times.[18] The survival function relates directly to the cumulative distribution function (CDF) , such that . For continuous survival times, the probability density function (PDF) is derived as , which describes the instantaneous rate of event occurrence at time .[19] These relationships provide the foundational probability framework for modeling time-to-event data.[20] The expected lifetime, or mean survival time, is obtained by integrating the survival function over all possible times: . This integral quantifies the average duration until the event, assuming the integral converges.[21] Quantiles of the survival distribution offer interpretable summaries, such as the median survival time, defined as the value where , representing the time by which half of the population is expected to experience the event. Higher or lower quantiles can similarly characterize the distribution's spread.[22] Formulations of the survival function differ between continuous and discrete time settings. In the continuous case, is differentiable almost everywhere, linking to the hazard function via . In discrete time, where events occur at integer times, the survival function is expressed as the product , with denoting the discrete hazard at time .[23] Common parametric families for the survival function include the exponential, Weibull, and log-normal distributions, each characterized by shape and scale parameters that capture different hazard behaviors. The exponential distribution assumes a constant hazard, with , where is the rate parameter (scale inverse).[24] The Weibull distribution generalizes this, allowing increasing, decreasing, or constant hazards via , where is the scale parameter and is the shape parameter (with reducing to exponential).[25] The log-normal distribution models survival times that are log-normally distributed, with , where is the standard normal CDF, is the location parameter (log-scale), and is the shape parameter.[26] These distributions are widely used due to their flexibility in fitting empirical survival patterns across applications like reliability engineering and medical research.[27]Hazard Function and Cumulative Hazard

The hazard function, denoted , represents the instantaneous rate at which events occur at time , given survival up to that time. Formally, it is defined as where is the survival time random variable.[28] This limit expression captures the conditional probability of the event happening in a small interval following , divided by the interval length, as the interval approaches zero. Equivalently, can be expressed in terms of the probability density function and the survival function as , where is the probability of surviving beyond time .[19] The cumulative hazard function, , accumulates the hazard over time up to and is given by the integral This function relates directly to the survival function through the identity , which implies .[19] The relationship between the density, hazard, and survival functions follows as , since and substituting yields the derivative form . These interconnections highlight how the hazard provides a dynamic view of risk, contrasting with the static probability encoded in .[1] In interpretation, the hazard function is often termed the force of mortality in demographic contexts or the failure rate in reliability engineering, quantifying the intensity of the event risk at each instant conditional on prior survival.[1] A key assumption in many survival models is that of proportional hazards, where the hazard for individuals with covariates takes the multiplicative form , with as the baseline hazard for a reference group (e.g., when ). This posits that covariates act to scale the underlying time-dependent hazard shape by a constant factor, independent of time.[28] Hazard functions exhibit varying shapes depending on the underlying survival distribution. For the exponential distribution, the hazard is constant, , reflecting memoryless event timing where risk does not change with survival duration.[19] In contrast, the Weibull distribution produces an increasing hazard when the shape parameter , as , modeling scenarios like aging processes where failure risk accelerates over time.[19]Censoring Mechanisms

In survival analysis, censoring refers to the incomplete observation of event times due to the study design or external factors, which complicates the estimation of survival distributions and requires specialized statistical methods to avoid bias.[29] Censoring arises because subjects may exit the study before the event of interest occurs, or the event may happen outside the observation window, leading to partial information about their survival times.[7] Unlike complete data scenarios, ignoring censoring can result in biased estimates of survival probabilities and underestimated variances, as it treats censored observations as events or failures, distorting the risk set and inflating the apparent incidence of events.[30] For instance, in clinical trials, failing to account for censoring might overestimate treatment effects by excluding longer survival times from censored subjects.[31] Right censoring is the most prevalent type, occurring when the event has not been observed by the end of the study period or due to subject withdrawal.[32] Type I right censoring happens at a fixed study endpoint, where all remaining subjects are censored regardless of their status, common in prospective studies with predefined durations. In contrast, Type II right censoring involves censoring at a fixed number of events, often used in reliability testing where observation stops after a set number of failures, though it is less common in biomedical contexts due to ethical concerns.[33] Dropout due to loss to follow-up also induces right censoring, assuming it is unrelated to the event risk.[29] Left censoring occurs when the event has already happened before the observation period begins, providing only an upper bound on the event time.[7] This is typical in cross-sectional studies or retrospective analyses where entry into the study follows the event, such as diagnosing chronic conditions after onset.[34] Interval censoring extends this idea, where the event time is known only to fall within a specific interval between two observation points, rather than an exact time or bound.[35] For example, in periodic health screenings, the event might be detected between visits without pinpointing the exact occurrence. Truncation differs from censoring in that it entirely excludes subjects whose event times fall outside the observation window, rather than including partial information.[32] Left truncation, for instance, removes individuals who experienced the event before study entry, potentially biasing the sample toward longer survivors if not adjusted for, as seen in registry data where only post-enrollment cases are captured.[34] Right truncation similarly omits events after the study cutoff. Unlike censoring, which retains subjects in the risk set until their censoring time, truncation alters the population representation entirely. A key assumption underlying most survival analysis methods is non-informative censoring, where the censoring mechanism is independent of the event time given the covariates, ensuring that censored subjects have the same future event risk as non-censored ones.[7] Violation of this assumption, such as when censoring correlates with poorer prognosis (e.g., withdrawal due to worsening health), introduces informative censoring, leading to biased hazard estimates and invalid inferences. Methods like the Kaplan-Meier estimator address right censoring by incorporating censored observations into the risk set without treating them as events, thereby providing unbiased survival curve estimates under the non-informative assumption.[29]Estimation Techniques

Non-parametric Methods

Non-parametric methods in survival analysis provide distribution-free approaches to estimate survival functions and compare groups without assuming a specific underlying probability distribution for survival times. These techniques are particularly valuable when the form of the survival distribution is unknown or complex, allowing for flexible estimation in the presence of censoring. The primary tools include estimators for the survival and cumulative hazard functions, as well as tests for comparing survival experiences across groups. The Kaplan-Meier estimator is a cornerstone non-parametric method for estimating the survival function from right-censored data. It constructs the estimator as a product-limit formula: for ordered distinct event times , the estimated survival function is given by where is the number of individuals at risk just prior to time , and is the number of events observed at . This estimator is unbiased and consistent under standard conditions, providing a step function that decreases only at observed event times. To assess its variability, Greenwood's formula offers an estimate of the variance: which approximates the asymptotic variance and is used to construct confidence intervals, such as those based on the normal approximation to the log-cumulative hazard. This variance estimator conditions on the observed censoring pattern and performs well even with moderate sample sizes. (Note: Greenwood's original work on variance estimation for life tables predates the Kaplan-Meier method but was adapted for its use.) Complementing the Kaplan-Meier estimator, the Nelson-Aalen estimator provides a non-parametric estimate of the cumulative hazard function, defined as This estimator accumulates the incremental hazards at each event time and serves as a basis for deriving the Kaplan-Meier survival estimate via the relationship in the continuous case, though the product-limit form is preferred for discrete data to avoid bias. The Nelson-Aalen approach is asymptotically equivalent to the Kaplan-Meier under the exponential transformation and is particularly useful for modeling hazard processes directly. Its variance can be estimated similarly using . For comparing survival curves between two or more groups, the log-rank test is a widely used non-parametric hypothesis test that assesses whether there are differences in survival distributions. The test statistic is constructed by comparing observed events in group to expected events under the null hypothesis of identical hazards across groups, typically following a chi-squared distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the number of groups minus one. At each event time, , where is the number at risk in group just before . The overall statistic is , providing a sensitive test for detecting differences, especially under proportional hazards. A classic application of these methods is in analyzing survival data from patients with acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), as studied in early chemotherapy trials. Consider a simplified life table from the 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) arm of a cohort of 21 AML patients, where survival times are right-censored for some individuals; the data track remission duration post-treatment (9 events, 12 censored observations). The table below illustrates the construction for the Kaplan-Meier estimator, showing event times, individuals at risk (), and deaths ():| Time (weeks) | Survival Probability | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 21 | 3 | 0.857 |

| 7 | 17 | 1 | 0.807 |

| 10 | 15 | 1 | 0.753 |

| 13 | 12 | 1 | 0.690 |

| 16 | 11 | 1 | 0.628 |

| 22 | 7 | 1 | 0.538 |

| 23 | 6 | 1 | 0.448 |

![{\displaystyle s(t)=S'(t)={\frac {d}{dt}}S(t)={\frac {d}{dt}}\int _{t}^{\infty }f(u)\,du={\frac {d}{dt}}[1-F(t)]=-f(t).}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/aef0f76f4ba2197d146ecf3b9c3d50d7eb4fdb16)

![{\displaystyle [0,\infty ]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/52088d5605716e18068a460dec118214954a68e9)

![{\displaystyle S(t)=\exp[-\Lambda (t)]={\frac {f(t)}{\lambda (t)}}=1-F(t),\quad t>0.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/17e4e85965ac80b7f00e988635a4d8253be2cd6d)