Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Fayolism

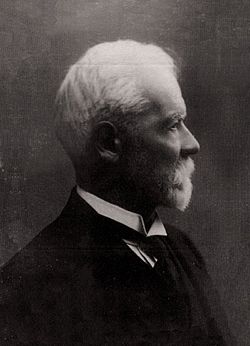

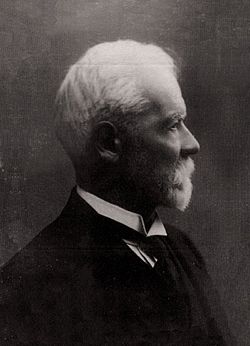

View on WikipediaFayolism was a theory of management that analyzed and synthesized the role of management in organizations, developed around 1900 by the French manager and management theorist Henri Fayol (1841–1925). It was through Fayol's work as a philosopher of administration that he contributed most widely to the theory and practice of organizational management.

Research and teaching of management

[edit]Fayol served as the CEO of Compagnie de Commentry-Fourchambault-Decazeville from 1888 onward and methodically analysed the company's operations. He believed that by focusing on managerial practices, he could minimize misunderstandings and increase organizational efficiency.[1] He instructed managers on how to fulfill their duties and the specific practices they should adopt. In his book General and Industrial Management (published in French in 1916 and in English in 1949), Fayol outlined a theory of general management that he believed could be applied across myriad industries. His primary concern was with the administrative apparatus, or functions of administration. To that end, he presented his administrative theory, which consisted of both principles and elements of management.

He believed in control and a strict, tree-like, chain of command. Unity of command, the principle that workers should receive orders from only one superior, was one of his major mottoes. He believed that while production and productivity were important, they were not the only factors for success. Other departments (such as sales, finance, and accounting) and human-centric focuses (such as safety, harmony, and unity of purpose) were equally vital. However, General and Industrial Management reveals that Fayol advocated for a flexible approach to management, applicable to various contexts including the home, the workplace, or the state. He stressed the practice of forecasting and planning to adapt to any situation. He also outlines an agenda where every citizen would receive management education, allowing them to exercise these abilities starting in school and continuing into the workplace.

Everyone needs some concepts of management; in the home, in affairs of state, the need for managerial ability is in keeping with the importance of the undertaking, and for individual people the need is everywhere in greater accordance with the position occupied.

— excerpt from General and Industrial Management

Fayol vs. Frederick Taylor's Scientific Management

[edit]Fayol has been regarded by many as the father of the modern operational management theory, and his ideas have become a fundamental part of modern management concepts. Fayol is often compared to Frederick Winslow Taylor, who developed Scientific Management.[citation needed] Taylor's system of Scientific Management is the cornerstone of classical theory. Fayol was also a classical theorist. While Taylor knew nothing of Fayol, Fayol read Taylor and referred to him in his writing. He considered him a visionary and pioneer in the management of organizations, and praised him, but also criticized some points.

Fayol differed from Taylor in his focus. Taylor's main focus was on the task, whereas Fayol was more concerned with management. Taylor's Scientific Management deals with the efficient organization of production in the context of a competitive enterprise concerned with controlling production costs. Fayol, however, left this to the technical executives and operatives, and put emphasis on the leadership, orderly organization, communication, and harmony between departments, what he called administration. According to Fayol, administration applies to virtually every business and organisation (including non-profit, churches, armies, etc.), whether small or large. Another difference between the two theorists is their treatment of workers. Fayol appears to have slightly more respect for the worker than Taylor had, as evidenced by Fayol's proclamation that workers may indeed be motivated by more than just money, and his practice of giving them opportunities to learn and move up the ladder. Fayol also argued for equity in the treatment of workers. He discussed how workers should receive their wages, whether this should be fixed salaries, bonus payments, or a portion of the dividends. He also considered different bases for pay, such as calculation by time worked, tasks completed, or units produced.

According to Claude George (1968), a primary difference between Fayol and Taylor was that Taylor viewed management processes from the bottom up, while Fayol viewed it from the top down. In Fayol's book General and Industrial Management, Fayol wrote that:

Taylor's approach differs from the one we have outlined in that he examines the firm from the bottom up. He starts with the most elemental units of activity—the workers' actions—then studies the effects of their actions on productivity, devises new methods for making them more efficient, and applies what he learns at lower levels to the hierarchy...

— Fayol, 1987, p. 43

He suggests that Taylor has staff analysts and advisors working with individuals at lower levels of the organization to identify ways to improve efficiency. According to Fayol, this approach results in a "negation of the principle of unity of command". Fayol criticized Taylor’s functional management in this way:

… the most marked outward characteristics of functional management lies in the fact that each workman, instead of coming in direct contact with the management at one point only, … receives his daily orders and help from eight different bosses…

— Fayol, 1949, p. 68.

Those eight, Fayol said, were:

- route clerks,

- instruction card men

- cost and time clerks

- gang bosses

- speed bosses

- inspectors

- repair bosses, and the

- shop disciplinarian (p. 68).

This, he said, was an unworkable situation, and that Taylor must have somehow reconciled the dichotomy in a way not described in Taylor's works, but crucial for it to actually work in the field.

Fayol's desire for teaching a generalized theory of management stemmed from the belief that each individual of an organization, at one point or another, takes on duties that involve managerial decisions. This contrasts with Taylor, who believed management activity was the exclusive duty of an organization's dominant class. Fayol's approach was more in sync with his idea of Authority, which stated, "...that the right to give orders should not be considered without the acceptance and understanding of responsibility."

Noted as one of the early fathers of the Human Relations movement, Fayol expressed ideas and practices different from Taylor's, showing flexibility and adaptation, and stressing the importance of interpersonal interaction among employees.

Fayol's Principles of Management

[edit]During the early 20th century, Fayol developed 14 principles of management to help managers manage their affairs more effectively. Organizations in technologically advanced countries interpret these principles quite differently from the way they were interpreted during Fayol's time. These differences in interpretation are in part a result of the cultural challenges managers face when implementing this framework. The fourteen principles are:[2]

- Division of work

- Delegation of authority and responsibilities

- Discipline

- Unity of commands

- Unity of direction

- Subordination or Interrelation between individual interests and common organizational goals

- Compensation package or Remuneration

- Centralization And Decentralisation

- Scalar chains

- Order

- Equity

- Job guarantee or Stability of Employees

- Initiatives

- Team-Spirit or Esprit de corps

Fayol goes on to describe how each organizational component has certain properties attached to it, depending on its role in contributing to the organization or group. This essential function, or activities, corresponds to a set of abilities that are appropriate in order to carry out the duties associated with the properties of this essential function, or activities. In order to match this specified set of abilities that are required for the organizational role, a profile of which number of requisite abilities necessary for the role in question has to be established.[3][4] This thesis has since been subject to application in 21st century organizational theory.[5]

Fayol's Elements (or functions) of Management

[edit]Within his theory, Fayol outlined five elements of management that depict the kinds of behaviors managers should engage in so that the goals and objectives of an organization are effectively met.[6] The five elements of management are:

- Planning: creating a plan of action for the future, determining the stages of the plan and the technology necessary to implement it. Deciding in advance what to do, how to do it, when to do it, and who should do it. It maps the path from where the organization is to where it wants to be. The planning function involves establishing goals and arranging them in a logical order. Administrators engage in both short-range and long-range planning.

- Organizing: Once a plan of action is designed, managers need to provide everything necessary to carry it out; including raw materials, tools, capital and human resources. Identifying responsibilities, grouping them into departments or divisions, and specifying organizational relationships.

- Command: Managers need to implement the plan. They must have an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of their personnel. Leading people in a manner that achieves the goals of the organization requires proper allocation of resources and an effective support system. Directing requires exceptional interpersonal skills and the ability to motivate people. One of the crucial issues in directing is the correct balance between staff needs and production.

- Coordination: High-level managers must work to "harmonize" all the activities to facilitate organizational success. Communication is the prime coordinating mechanism. Synchronizes the elements of the organization and must take into account delegation of authority and responsibility and span of control within units.

- Control: The final element of management involves the comparison of the activities of the personnel to the plan of action, it is the evaluation component of management. Monitoring function that evaluates quality in all areas and detects potential or actual deviations from the organization's plan, ensuring high-quality performance and satisfactory results while maintaining an orderly and problem-free environment. Controlling includes information management, measurement of performance, and institution of corrective actions.

Effects of Written Communication

[edit]Fayol believed that animosity and unease within the workplace occurred among employees in different departments.[7] Many of these "misunderstandings" were thought to be caused by improper communication, mainly through letters (or in present-day emails). Among scholars of organizational communication and psychology, letters were perceived to induce or solidify a hierarchical structure within the organization. Through this type of vertical communication, many individuals gained a false feeling of importance. Furthermore, it gave way to selfish thinking and eventual conflict among employees in the workplace.

This concept was expressed in Fayol's book, General and Industrial Management, by stating," in some firms... employees in neighboring departments with numerous points of contact, or even employees within a department, who could quite easily meet, communicate with each other in writing... there is to be observed a certain amount of animosity prevailing between different departments or different employees within a department. The system of written communication usually brings this result. There is a way of putting an end to this deplorable system ... and that is to forbid all communication in writing which could easily and advantageously be replaced by verbal ones."

Administrative theory in the modern workplace

[edit]

Fayol believed that managerial practices were key to predictability and efficiency in organizations. The administrative theory views communication as a necessary ingredient to successful management and many of Fayol's practices are still alive in today's workplace.[8] The elements and principles of management can be found in modern organizations in several ways: as accepted practices in some industries, as revamped versions of the original principles or elements, or as remnants of the organization's history to which alternative practices and philosophies are being offered.[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Pietri, P. H (1974). "Organizational communication: the pioneers". Journal of Business Communication. 11 (4): 3–6. doi:10.1177/002194367401100401. S2CID 143975024.

- ^ Chaudhary, Sujan (2023-12-24). "Henri Fayol's 14 Principles of Management". theMBAins. Archived from the original on 2025-10-09. Retrieved 13 December 2025.

- ^ General and industrial management. London: Pitman. 1949. OCLC 825227.

- ^ Jang, Yong Suk; Ott, J. Steven; Shafritz, Jay M. (2015). Classics of Organization Theory (8 ed.). Cengage Learning. ISBN 9781305688056.

- ^ Baligh, Helmy H. (2006). Organizational Structures: Theory and Design, Analysis and Prescription. Information and Organization Design Series. Vol. 5 (1 ed.). New York, NY: Springer. doi:10.1007/0-387-28317-X. ISBN 978-1-4419-3841-1.

- ^ Fayol, H. (1917). Administration industrielle et générale: prévoyance, organisation, commandement, coordination, contrôle (in French). Dunod. Retrieved 2022-10-12.

- ^ Brunsson, K. (2008). "Some Effects of Fayolism". International Studies of Management & Organization. 38 (1): 30–47. doi:10.2753/IMO0020-8825380102. S2CID 145734884.

- ^ McLean, Jacqueline (2011). "Fayol-Standing the test of time". British Journal of Administrative Management (74): 32–33.

Further reading

[edit]- Breeze, John D., and Frederick C. Miner. "Henri Fayol: A New Definition of "Administration"." Academy of Management Proceedings. Vol. 1980. No. 1. Academy of Management, 1980.

- Fayol, Henri, and John Adair Coubrough. Industrial and general administration. (1930).

- Fayol, Henri. General and industrial management. (1954).

- Fayol, Henri. General Principles of Management. (1976).

- Modaff, Daniel P., Sue DeWine, and Jennifer A. Butler. Organizational communication: Foundations, challenges, and misunderstandings. Pearson/Allyn & Bacon, 2008.

- Pearson, Norman M. "Fayolism as the necessary complement of Taylorism." American Political Science Review 39.01 (1945): 68-80.

- Parker, Lee D., and Philip A. Ritson. "Revisiting Fayol: anticipating contemporary management." British Journal of Management 16.3 (2005): 175-194.

- Pugh, Derek S. "Modern organization theory: A psychological and sociological study." Psychological Bulletin 66.4 (1966): 235.

- Reid, Donald. "The genesis of fayolism." Sociologie du travail 28.1 (1986): 75-93.

- Carl A Rodrigues. (2001). "Fayol's 14 principles of management then and now: A framework for managing today's organizations effectively." Management Decision, 39(10), 880-889.

- Wren, Daniel A. "Was Henri Fayol a Real Manager?." Academy of Management Proceedings. Vol. 1990. No. 1. Academy of Management, 1990.

Fayolism

View on GrokipediaOrigins and Historical Context

Henri Fayol's Life and Career

Henri Fayol was born on July 29, 1841, in Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey), to French parents; his father, an engineer, was overseeing the construction of the Galata Bridge for the Ottoman government.[7] The family returned to France in 1844, settling initially in Toulouse before moving to the Rhône Valley, where Fayol received his early education at a Marist school and a public college in Valence.[8] He later attended the Lycée de Lyon from 1856 to 1857 and was admitted to the École Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Saint-Étienne in 1857, graduating in 1860 as a mining engineer with second place in his class.[9] Fayol began his professional career that same year, joining the Compagnie de Commentry-Fourchambault-Decazeville, a French mining and metallurgical firm, as an assistant engineer during his final studies and becoming a full engineer upon graduation.[10] Over the next two decades, he advanced through various technical and administrative roles, demonstrating expertise in mining operations and geology. In 1888, amid the company's financial crisis—with declining coal reserves, outdated facilities, and near-bankruptcy—Fayol was appointed managing director, a position he held until 1918.[11] Through strategic restructuring, cost controls, and innovative administrative practices, he orchestrated a remarkable turnaround; by 1900, the firm had achieved profitability and expanded production, with its workforce growing to over 10,000 workers by the 1910s, establishing it as a leading industrial enterprise in France.[11] After retiring as managing director in 1918, Fayol remained as honorary director while dedicating himself to disseminating his management insights through writing and lectures at institutions like the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers.[10] His early contributions to management literature included articles presented at the 1900 International Congress of Mines and Metallurgy and published in the Bulletin de la Société de l'Industrie Minérale in 1901, where he first outlined elements of administrative theory.[12] Fayol's most influential work, Administration Industrielle et Générale, appeared in 1916 as a collection of papers emphasizing foresight, organization, command, coordination, and control; it was translated into English as General and Industrial Management in 1949, broadening his global impact.[3] He passed away on November 19, 1925, in Paris at the age of 84.[7]Development of Fayol's Administrative Theory

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, France underwent rapid industrialization, particularly in mining and manufacturing sectors, which brought significant labor unrest, efficiency challenges, and demands for improved organizational management amid economic pressures following the Franco-Prussian War.[13][14] This context was marked by strikes, resource constraints, and the need to enhance productivity in heavy industries like coal mining, where Fayol served as a prominent executive.[15] As managing director of the Commentry-Fourchambault-Decazeville mining company from 1888, Fayol observed persistent operational inefficiencies, such as poor coordination and resource allocation, which he attributed to a lack of systematic administrative approaches.[14] Motivated by these issues, he sought to develop general principles of administration applicable to all organizations—industrial, governmental, or otherwise—contrasting with narrower, task-specific methods prevalent at the time.[12] His approach emphasized management as a distinct, teachable skill separate from technical expertise, analyzed primarily from a top-level organizational perspective to foster overall efficiency and foresight.[13][14] Key milestones in the theory's formulation included Fayol's presentation at the 1900 International Mining and Metallurgical Congress in Paris, where he first outlined the need for universal administrative principles to address industrial challenges.[12][15] Following the 1916 publication of Administration Industrielle et Générale, he established the Centre for Administrative Studies (CAS) in 1917 to promote research, teaching, and application of administrative theory across sectors.[14][16] Initially, Fayol's ideas had limited impact in France due to the disruptions of World War I, which hindered dissemination and overshadowed managerial discourse with wartime priorities.[15][17] Their prominence grew internationally after the 1949 English translation of his work as General and Industrial Management by Constance Storrs, which introduced his concepts to a broader audience, particularly in the United States and Britain.[14][12]Core Elements of Fayolism

The 14 Principles of Management

Henri Fayol outlined the 14 Principles of Management in his 1916 book Administration Industrielle et Générale, later translated as General and Industrial Management in 1949, as fundamental truths derived from his observations of organizational practices. These principles aim to guide administrative efficiency by promoting structure, coordination, and harmony within enterprises, applicable to both profit and non-profit settings. Fayol viewed them as flexible tools rather than inflexible rules, emphasizing their adaptation to specific contexts to achieve optimal results.[18] The principles are interconnected, with elements like authority supporting discipline and unity of command facilitating scalar chain communication, forming a cohesive system for managerial decision-making across all organizational levels.- Division of Work: This principle posits that specialization through dividing tasks among workers enhances efficiency, accuracy, and output, as repeated performance builds expertise and reduces errors. Its purpose is to optimize productivity by assigning roles to those best suited, applicable from manual labor to executive functions.[19][18]

- Authority and Responsibility: Managers must possess the right to give orders, coupled with the responsibility for outcomes, ensuring accountability balances power. The purpose is to enable decisive action while preventing abuse, fostering trust in leadership.[19][18]

- Discipline: Obedience and respect for organizational agreements, enforced through fair leadership and clear sanctions, maintain order. Its purpose is to align individual efforts with collective goals, improving overall performance and morale.[19][18]

- Unity of Command: Each employee should receive instructions from only one superior to avoid confusion and conflicting priorities. The purpose is to ensure clarity in directives, preserving discipline and operational stability.[19][18]

- Unity of Direction: Activities with similar objectives must be coordinated under a single plan and leader to achieve synergy. Its purpose is to unify efforts toward common goals, preventing fragmentation and enhancing effectiveness.[19][18]

- Subordination of Individual Interests to the General Interest: The organization's collective goals should prevail over personal ambitions, guided by managerial oversight. The purpose is to safeguard enterprise harmony and progress by mitigating self-serving behaviors.[19][18]

- Remuneration: Compensation should be fair and equitable, encompassing monetary and non-monetary incentives to motivate employees. Its purpose is to satisfy both parties, reducing dissatisfaction and boosting commitment.[19][18]

- Centralization: The degree of decision-making concentration at the top varies by organizational size and circumstances, balancing top-level control with delegation. The purpose is to optimize authority distribution for maximum efficiency and adaptability.[19][18]

- Scalar Chain: A clear line of authority from top to bottom ensures hierarchical communication, with allowances for lateral exchanges when beneficial. Its purpose is to facilitate orderly information flow and problem resolution.[19][18]

- Order: Resources and personnel must be in the right place at the right time, promoting systematic arrangement of materials and social factors. The purpose is to minimize idleness, waste, and disorder, supporting smooth operations.[19][18]

- Equity: Managers should treat employees with kindness, justice, and impartiality, eliminating bias to build loyalty. Its purpose is to inspire devotion and reduce turnover through a supportive environment.[19][18]

- Stability of Tenure of Personnel: Long-term employment allows for skill development and reduces recruitment costs, favoring stability over frequent changes. The purpose is to cultivate experienced teams that enhance productivity and knowledge retention.[19][18]

- Initiative: Encouraging employees to develop and execute ideas fosters innovation and engagement. Its purpose is to harness collective intelligence, improving processes despite potential challenges to managerial ego.[19][18]

- Esprit de Corps: Promoting team spirit and unity through harmony and cohesion strengthens organizational morale. Its purpose is to integrate individual efforts for superior results, emphasizing "in union there is strength."[19][18]