Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Slip (aerodynamics)

View on Wikipedia

A slip is an aerodynamic state where an aircraft is moving somewhat sideways as well as forward relative to the oncoming airflow or relative wind. In other words, for a conventional aircraft, the nose will be pointing in the opposite direction to the bank of the wing(s). The aircraft is not in coordinated flight and therefore is flying inefficiently.

Background

[edit]Flying in a slip is aerodynamically inefficient, since the lift-to-drag ratio is reduced. More drag is at play consuming energy but not producing lift. Inexperienced or inattentive pilots will often enter slips unintentionally during turns by failing to coordinate the aircraft with the rudder. Airplanes can readily enter into a slip climbing out from take-off on a windy day. If left unchecked, climb performance will suffer. This is especially dangerous if there are nearby obstructions under the climb path and the aircraft is underpowered or heavily loaded.

A slip can also be a piloting maneuver where the pilot deliberately enters one type of slip or another. Slips are particularly useful in performing a short field landing over an obstacle (such as trees, or power lines), or to avoid an obstacle (such as a single tree on the extended centerline of the runway), and may be practiced as part of emergency landing procedures. These methods are also commonly employed when flying into farmstead or rough country airstrips where the landing strip is short. Pilots need to touch down with ample runway remaining to slow down and stop.

There are common situations where a pilot may deliberately enter a slip by using opposite rudder and aileron inputs, most commonly in a landing approach at low power.[1]

Without flaps or spoilers it is difficult to increase the steepness of the glide without adding significant speed. This excess speed can cause the aircraft to fly in ground effect for an extended period, perhaps running out of runway. In a forward slip much more drag is created, allowing the pilot to dissipate altitude without increasing airspeed, increasing the angle of descent (glide slope). Forward slips are especially useful when operating pre-1950s training aircraft, aerobatic aircraft such as the Pitts Special or any aircraft with inoperative flaps or spoilers.

Often, if an airplane in a slip is made to stall, it displays very little of the yawing tendency that causes a skidding stall to develop into a spin. A stalling airplane in a slip may do little more than tend to roll into a wings-level attitude. In fact, in some airplanes stall characteristics may even be improved.[2]

Forward-slip vs. sideslip

[edit]Aerodynamically these are identical once established, but they are entered for different reasons and will create different ground tracks and headings relative to those prior to entry. Forward-slip is used to steepen an approach (reduce height) without gaining much airspeed,[3] benefiting from the increased drag. The sideslip moves the aircraft sideways (often, only in relation to the wind) where executing a turn would be inadvisable, drag is considered a byproduct. Most pilots like to enter sideslip just before flaring or touching down during a crosswind landing.[4]

Forward-slip

[edit]The forward slip changes the heading of the aircraft away from the down wing, while retaining the original track (flight path over the ground) of the aircraft.

To execute a forward slip, the pilot banks into the wind and applies opposing rudder (e.g., right aileron + left rudder) in order to keep moving towards the target. If you were the target you would see the plane's nose off to one side, a wing off to the other side and tilted down toward you. The pilot must make sure that the plane's nose is low enough to keep airspeed up.[5] However, airframe speed limits such as VA and VFE must be observed.[6]

A forward-slip is useful when a pilot has set up for a landing approach with excessive height or must descend steeply beyond a tree line to touchdown near the runway threshold. Assuming that the plane is properly lined up for the runway, the forward slip will allow the aircraft track to be maintained while steepening the descent without adding excessive airspeed. Since the heading is not aligned with the runway, forward-slip must be removed before touchdown to avoid excessive side loading on the landing gear, and if a cross wind is present an appropriate sideslip may be necessary at touchdown as described below.

Sideslip

[edit]The sideslip also uses aileron and opposite rudder. In this case it is entered by lowering a wing and applying exactly enough opposite rudder so the airplane does not turn (maintaining the same heading), while maintaining safe airspeed with pitch or power. Compared to Forward-slip, less rudder is used: just enough to stop the change in the heading.

In the sideslip condition, the airplane's longitudinal axis remains parallel to the original flightpath, but the airplane no longer flies along that track. The horizontal component of lift is directed toward the low wing, drawing the airplane sideways. This is the still-air, headwind or tailwind scenario. In case of crosswind, the wing is lowered into the wind, so that the airplane flies the original track. This is the sideslip approach technique used by many pilots in crosswind conditions (sideslip without slipping). The other method of maintaining the desired track is the crab technique: the wings are kept level, but the nose is pointed (part way) into the crosswind, and resulting drift keeps the airplane on track.

A sideslip may be used exclusively to remain lined up with a runway centerline while on approach in a crosswind or be employed in the final moments of a crosswind landing. To commence sideslipping, the pilot rolls the airplane toward the wind to maintain runway centerline position while maintaining heading on the centerline with the rudder. Sideslip causes one main landing gear to touch down first, followed by the second main gear. This allows the wheels to be constantly aligned with the track, thus avoiding any side load at touchdown.

The sideslip method for crosswind landings is not suitable for long-winged and low-sitting aircraft such as gliders, where instead a crab angle (heading into the wind) is maintained until a moment before touchdown.

Aircraft manufacturer Airbus recommends sideslip approach only in low crosswind conditions.[7]

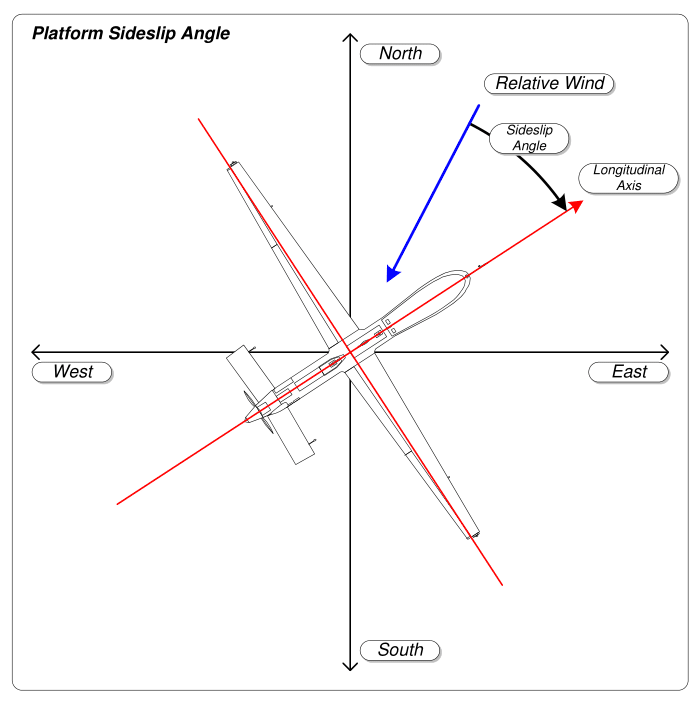

Sideslip angle

[edit]The sideslip angle, also called angle of sideslip (AOS, AoS, , Greek letter beta), is a term used in fluid dynamics and aerodynamics and aviation. It relates to the rotation of the aircraft centerline from the relative wind. In flight dynamics it is given the shorthand notation (beta) and is usually assigned to be "positive" when the relative wind is coming from the right of the nose of the airplane. The sideslip angle is essentially the directional angle of attack of the airplane. It is the primary parameter in directional stability considerations.[8]

In vehicle dynamics, side slip angle is defined as the angle made by the velocity vector to longitudinal axis of the vehicle at the center of gravity in an instantaneous frame. As the lateral acceleration increases during cornering, the side slip angle decreases. Thus at very high speed turns and small turning radius, there is a high lateral acceleration and could be a negative value.

Other uses of the slip

[edit]There are other, specialized circumstances where slips can be useful in aviation. For example, during aerial photography, a slip can lower one side of the aircraft to allow ground photos to be taken through a side window. Pilots will also use a slip to land in icing conditions if the front windshield has been entirely iced over—by landing slightly sideways, the pilot is able to see the runway through the aircraft's side window. Slips also play a role in aerobatics and aerial combat.

How a slip affects flight

[edit]When an aircraft is put into a forward slip with no other changes to the throttle or elevator, the pilot will notice an increased rate of descent (or reduced rate of climb). This is usually mostly due to increased drag on the fuselage. The airflow over the fuselage is at a sideways angle, increasing the relative frontal area, which increases drag.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Denker, John S. "11 Slips, Skids, and Snap Rolls". See How It Flies. Av8n.com. Archived from the original on Nov 11, 2023.

- ^ "Airport Traffic Patterns" (PDF). Airplane Flying Handbook. FAA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-27. Retrieved 2011-10-27.

- ^ Thom, Trevor (1993). The Flying Training Manual. Vic. Australia: Aviation Theory Centre P/L. p. 8/19. ISBN 187553718X.

- ^ Thom, Trevor (1993). The Flying Training Manual. Vic. Australia: Aviation Theory Centre P/L. p. 8/21. ISBN 187553718X.

- ^ "How to Perform a Forward Slip in a Cessna 152 to Descend Rapidly". wikihow.com. Archived from the original on 2020-02-24. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- ^ V speeds#Regulatory V-speeds

- ^ Airbus – Flight Operations Briefing Notes – Landing Techniques – Crosswind Landings

- ^ Hurt, H. H. Jr. (January 1965) [1960]. Aerodynamics for Naval Aviators. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C.: U.S. Navy, Aviation Training Division. pp. 284–85. NAVWEPS 00-80T-80.