Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

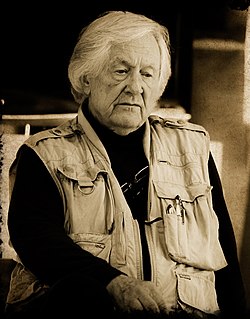

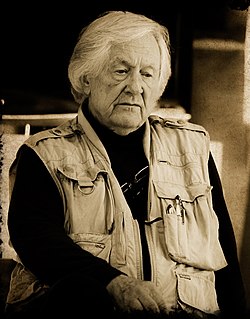

Gerry Spence

View on Wikipedia

Gerald Leonard Spence (January 8, 1929 – August 13, 2025) was an American trial lawyer and author. He was a member of the Trial Lawyer Hall of Fame and was the founder of the Trial Lawyers College.[2] Spence never lost a criminal trial before a jury, either as a prosecutor or a defense attorney,[a] and did not lose a civil trial after 1969, although several verdicts were overturned on appeal.[3][5][6] He is considered one of the greatest lawyers of the 20th century,[7][8] and among the best trial lawyers ever.[9][10][11][12][2] He has been described by legal scholar Richard Falk as a "lawyer par excellence".[13] The New York Times said that "in the tradition of Perry Mason, he seemed unbeatable."[3]

Key Information

Spence was recognized for winning nearly every case he ever handled,[10] including a number of high-profile cases, such as Randy Weaver at Ruby Ridge, the Ed Cantrell murder case, the Karen Silkwood case, and the defense of Geoffrey Fieger.[14] He also defended Brandon Mayfield,[15] and successfully prosecuted Mark Hopkinson as a special prosecutor.[16][17] One of his most significant cases was the defense of Imelda Marcos, former First Lady of the Philippines and first governor of Metro Manila, in a racketeering/fraud case considered one of the trials of the century,[18][19] which he won.[20][15]

Spence won multi-million-dollar lawsuits against corporations, such as $26.5 million in libel damages for 1978 Miss Wyoming Kim Pring against Penthouse in 1981.[21] He also won a $52 million lawsuit against McDonald's in 1984.[22] Spence won more multi-million dollar verdicts without an intervening loss than any lawyer in the United States.[23] Spence acted as a legal consultant for NBC during its coverage of the O. J. Simpson trial and appeared on Larry King Live.[14] He was the author of over a dozen books about politics and law, including The New York Times bestseller How to Argue and Win Every Time (1995), Win Your Case (2005), From Freedom to Slavery (1993), and Police State: How America's Cops Get Away with Murder (2015).[24]

Background

[edit]Gerry Spence was born in Laramie, Wyoming, on January 8, 1929.[25] He graduated from the University of Wyoming in 1949 and from the University of Wyoming College of Law in 1952, graduating first in his class.[26]

Spence was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree in May 1990. He started his career in Riverton, Wyoming, and later became a successful defense attorney for the insurance industry, winning many cases.[27] Years later, Spence said he "saw the light" and became committed to representing individuals instead of corporations, insurance companies, banks, or "big business."[28]

From 1954–1962, he served as prosecuting attorney of Fremont County, Wyoming.[3][29]

Spence and his second wife divided their time between their homes in Dubois, Wyoming, and Santa Barbara, California. Despite having residences in two different states, Spence stated that he would "die in Wyoming";[30] however, he died in California.[31]

High-profile cases

[edit]Karen Silkwood

[edit]Spence gained national attention during the Karen Silkwood case.[28] Karen Silkwood was a worker at the Kerr-McGee plutonium-production plant, where she became a whistleblower and activist concerned with workplace safety. On November 13, 1974, she died in a suspicious one-car crash after allegedly gathering evidence for her union and the New York Times.[32][33] Spence represented her family, who sued Kerr-McGee for exposing Silkwood to dangerous levels of radiation. Spence won a $10.5 million verdict for the family, but an appeals court reversed the verdict. After the ruling by the appeals court, the two sides later agreed to a settlement of $1.3 million.[3][29]

In 1984, the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the family's right to seek punitive damages under state law, even against a federally regulated industry.[32] The Silkwood case achieved international fame and was the subject of many books, magazine and newspaper articles, and the major motion picture Silkwood starring Meryl Streep as Karen Silkwood.[29][33]

Other cases

[edit]After the Silkwood case, Spence tried a number of high-profile cases. He did not lose a civil case after 1969 and never lost a criminal case with a trial by jury. By 1980, he had dealt with around 50 murder cases, not losing a single one of them.[34] Despite his tremendous success, he had several of his more prominent civil verdicts overturned on appeal and lost a 1985 manslaughter case in a bench trial in Newport, Oregon, in December 1985, later prevailing on appeal.[4]

He was known for taking up cases deemed to be unwinnable, such as the murder case of Joe Esquibel, who murdered his wife in front of multiple witnesses, yet Spence managed to gain his acquittal through reason of insanity.[35][36] He gained the acquittal of Sandy Jones for the murder of Wilfred Gerttula, and had the manslaughter conviction of her son, Michael Jones Jr., overturned on appeal.[37][38][39][40]

Spence successfully defended Randy Weaver on murder, assault, conspiracy, and gun charges in the 1992 Ruby Ridge Standoff, by successfully impugning the conduct of the FBI and its crime lab. Spence never called a witness for the defense. He relied only on contradictions and holes in the prosecution's story. Spence later wrote that he rejected Weaver's extremist political opinions, but took the case because he believed Federal officials had entrapped Weaver and also behaved unconscionably in shooting Weaver's unarmed wife.[41] In another case, he successfully gained the acquittal of a young janitor who had confessed to stabbing a woman to death.[10]

He gained the acquittal of Ed Cantrell in a Rock Springs, Wyoming murder case that alleged that Cantrell murdered a police officer who was going to testify about allegations that the local authorities protected the activities of a large number of prostitutes and pimps in Rock Springs.[42][43]

Spence won the acquittal of former Filipino First Lady Imelda Marcos in New York City on federal racketeering charges.[29] He also defended Earth First! founder David Foreman, who in 1990 had been charged with conspiracy for an alleged plot to sabotage a water-pumping station.[44]

On June 2, 2008, Spence obtained an acquittal of Detroit lawyer Geoffrey Fieger, who was charged with making unlawful campaign contributions. Before returning a not-guilty verdict, the federal court jury deliberated 18 hours over four days. The acquittal maintained Spence's record of never having lost a jury trial in a criminal matter.[4]

In civil litigation, Spence won a $52 million verdict against McDonald's Corporation on behalf of a small, family-owned ice cream company.[45] A medical malpractice verdict of over $4 million established a new standard for nursing care in Utah. In 1992 Spence earned $33.5 million verdicts for emotional and punitive damages for his quadriplegic client after a major insurance company refused to pay on the $50,000 policy.[46]

Mock trial: United States v. Oswald

[edit]In 1986, Spence defended in absentia Lee Harvey Oswald, the deceased assassin of U.S. President John F. Kennedy, against well-known prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi in a 21-hour televised unscripted mock trial sponsored by London Weekend Television in the United Kingdom.[47] The mock trial involved an actual U.S. judge, a jury of U.S. citizens, the introduction of hundreds of evidence exhibits, and many actual witnesses to events surrounding and including the assassination. The jury returned a guilty verdict. Expressing admiration for his adversary's prosecutorial skill, Spence remarked, "No other lawyer in America could have done what Vince did in this case."[48] The "docu-trial" and his preparation for it inspired Bugliosi's 1600-page book examining the details of the Kennedy assassination and various related conspiracy theories, entitled Reclaiming History, winner of the 2008 Edgar Award for Best Fact Crime.[49] Several times in the book Bugliosi specifically cites his respect for Spence's abilities as a defense attorney as his impetus for digging more deeply into various aspects of the case than he perhaps would have otherwise.[50]

Tort reform activism

[edit]During the election season of 2004, Spence, a vocal opponent of tort reform, crisscrossed his native Wyoming spearheading a series of self-funded town hall-style meetings to inform voters of an upcoming ballot measure, Constitutional Amendment D, which would have limited Wyoming citizens' ability to recover compensation if injured by medical malpractice. The ballot measure failed, with a 50.3% "No" vote.[51]

Public interest and television work

[edit]For many years, Spence taught, lectured at law schools and conducted seminars at various legal organizations around the country.[52] He founded and served as director of the non-profit Trial Lawyers College (now known as the "Gerry Spence Method"), where, per its mission statement, lawyers and judges "committed to the jury system" are trained to help achieve justice for individuals fighting "corporate and government oppression", particularly those individuals who could be described as "the poor, the injured, the forgotten, the voiceless, the defenseless and the damned".[53] Teachers at the school have been Richard "Racehorse" Haynes, Morris Dees from the Southern Poverty Law Center and John Gotti defense lawyer Albert Krieger.[10]

Spence was also the founder of Lawyers and Advocates for Wyoming, a pro bono law firm that represents the poor.[23] He served as legal consultant for NBC television covering the O. J. Simpson trial and appeared on The Oprah Winfrey Show, Larry King Live, and Geraldo. He had his own talk show on CNBC from 1995 to 1996.[2][14] He received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement in 1996.[54]

Later life and death

[edit]After winning the Fieger acquittal in 2008, Spence told jurors, "This is my last case. I will be 80 in January, and it's time for me to quit, to put down the sword."[55] In 2010, however, Spence was still listed as an active partner in the Spence Law Firm, located in Jackson, Wyoming, and continued to make public appearances.[56] Despite his claim of retirement, Spence took on a civil suit for wrongful incarceration, which ended with a mistrial in December 2012 when the jury could not come to a unanimous decision.[57] According to the cite to the AP story: "The verdicts Pratt read in court indicated jurors had found in favor of Larsen, Brown and the city of Council Bluffs on both major issues. The first issue was whether Harrington and McGhee's constitutional rights to due process had been violated. The second was whether the city had failed to adequately train and supervise the police officers. When the judge polled the jurors to ensure all agreed, three women said no." In October 2013, the AP reported that the suit was settled between the two parties four days before a retrial was scheduled to start.[58]

Spence was selected as a top lawyer by Super Lawyers between 2008 and 2022.[59] He received the first Lifetime Achievement Award from Consumer Attorneys of California in 2008.[60][61] He also received the American Association for Justice's Lifetime Achievement Award in 2013.[62][63]

Spence later oversaw The Gerry Spence Method program, which trains trial lawyers who represent injured people and people accused of crimes; no corporate or government lawyers are allowed to attend.[64] Gerry Spence was one of the longest-serving lawyers, having worked for over 70 years.[65]

Spence died at his home in Montecito, California, on August 13, 2025, at the age of 96.[31]

Partial bibliography

[edit]Spence was the author of more than a dozen books, including:

- Gunning for Justice – My Life and Trials (Doubleday 1982) ISBN 978-0-385-17703-0

- Of Murder and Madness: A True Story of Insanity and the Law (Doubleday 1983) ISBN 978-0-385-18801-2

- Trial by Fire: The True Story of a Woman's Ordeal at the Hands of the Law (William Morrow 1986) ISBN 978-0-688-06075-6

- With Justice for None: Destroying an American Myth (Times Books 1989) ISBN 978-0-14-013325-7

- From Freedom to Slavery: The Rebirth of Tyranny in America (St. Martin's Press 1993) ISBN 978-0-312-14342-8

- How to Argue & Win Every Time: At Home, At Work, In Court, Everywhere, Everyday (St. Martin's Press 1995) ISBN 0-312-14477-6

- The Making of a Country Lawyer (St. Martin's Press 1996) ISBN 978-0-312-14673-3

- O. J.: The Last Word (St. Martin's Press 1997) ISBN 978-0-312-18009-6

- Give Me Liberty: Freeing Ourselves in the Twenty-First Century (St. Martin's Press 1998) ISBN 0-312-24563-7

- A Boy's Summer: Fathers and Sons Together (St. Martin's Press June 1, 2000) ISBN 978-0-312-20282-8

- Gerry Spence's Wyoming: The Landscape (St. Martin's Press October 19, 2000) ISBN 978-0-312-20776-2

- Half Moon and Empty Stars (Scribner, 2001) ISBN 0-7432-0276-7

- Seven Simple Steps to Personal Freedom: An Owner's Manual for Life (St. Martin's Griffin November 1, 2002) ISBN 978-0-312-30311-2

- The Smoking Gun: Day by Day Through a Shocking Murder Trial (Scribner 2003) ISBN 978-0-7432-4696-5

- Win Your Case: How to Present, Persuade, and Prevail—Every Place, Every Time (St. Martin's Press 2006) ISBN 0-312-36067-3

- Bloodthirsty Bitches and Pious Pimps of Power: The Rise and Risks of the New Conservative Hate Culture (St. Martin's Press 2006) ISBN 978-0-312-36153-2

- The Lost Frontier: Images and Narrative (Gibbs Smith October 1, 2013) ISBN 978-1-4236-3290-0

- Police State: How America's Cops Get Away with Murder (St. Martin's Press May 16, 2018) ISBN 978-1-250-07345-7

- So I Said: Quotes and Thoughts of Gerry Spence (Sastrugi Press September 8, 2018) ISBN 978-1-944986-38-4

- Court of Lies (Forge Books February 19, 2019) ISBN 978-1-250-18348-4

- The Martyrdom of Collins Catch the Bear (Seven Stories Press October 6, 2020) ISBN 978-1-60980-966-9

Notes

[edit]- ^ It is known that he lost a manslaughter bench trial in Oregon in 1985,[3] but he won when the verdict was appealed.[4]

References

[edit]- ^ Hubbell, Martindale (April 2000). Martindale-Hubbell Law Directory: Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, Puerto Rico & U.S. Territories (Volume 18 – 2000). Martindale-Hubbell. ISBN 978-1-56160-376-3.

- ^ a b c "Gerry Spence". Trial Lawyer Hall of Fame. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Gerry Spence, a Canny Courtroom Showman in Buckskin, Dies at 96". The New York Times. August 14, 2025.

- ^ a b c Spence, Gerry. The Smoking Gun; ISBN 0-7434-7052-4

- ^ Gerry Spence: home Archived December 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Carter, Terry (June 2, 2008). "Spence's No-Loss Record Stands with Fieger Acquittal". ABA Journal. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ Solovy, Jerold S.; Byman, Robert L. (1999). "The Timeless Litigator". Litigation. 26 (1): 12–18. ISSN 0097-9813. JSTOR 29760099.

- ^ Uelmen, Gerald (January 1, 2000). "Who Is the Lawyer of the Century". Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review. 33 (2): 613. ISSN 0147-9857.

- ^ Gillins, Peter (January 1, 1989). "Famed cowboy lawyer packs Oregon courtroom". UPI. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Heath, Thomas (September 6, 1995). "GERRY SPENCE, ATTORNEY AT LORE". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ Solovy, Jerold S.; Byman, Robert L. (1999). "The Timeless Litigator". Litigation. 26 (1): 12–18. ISSN 0097-9813. JSTOR 29760099.

- ^ Bennett, Mark W. (2014). "Eight Traits of Great Trial Lawyers: A Federal Judge's View on How to Shed the Moniker 'I Am a Litigator'". SSRN 2491035.

- ^ Falk, Richard (December 11, 2015). "Gerry Spence on America Menaced by Impending Police State". Global Justice in the 21st Century. Retrieved November 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c "The Legacy of Gerry Spence". www.spencelawyers.com. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ a b Levenson, Laurie L. (September 14, 2015). "Gerry Spence and His Fight Against Power". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ McCullen, Kevin (June 11, 1992). "A 'REAL PEOPLE' LAWYER'S HARDEST CASE". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ Hoffman, Jan (October 15, 1993). "A Triumph of One Man's Personality: The American Courtroom's Buffalo Bill". The New York Times. Retrieved October 29, 2024.

- ^ Bareng, Eriza Ong (2018). Steeling the Butterfly: The Imperial Constructions of Imelda Marcos 1966–1990 (PDF) (PhD thesis). University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa.

- ^ Live Awake PH (November 10, 2021), Gerry Spence, Imelda Marcos' Defense Lawyer in the Trial of the Century, retrieved November 16, 2023

- ^ Tisdall, Simon (July 3, 2015). "From the archive, 3 July 1990: Tears and cheers as Imelda cleared". The Guardian.com. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ Polk, Anthony (February 21, 1981). "$26.5 Million Libel Award". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ "AROUND THE NATION; Ice Cream Maker Wins Suit on Oral Contract". The New York Times. AP. January 22, 1984. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ a b "Gerry Spence". Gerry Spence Method. Retrieved November 17, 2023.

- ^ "Gerry Spence". Trial Guides. Retrieved November 16, 2023.

- ^ "Gerry Spence, Legendary 'Country Lawyer,' Dies at 96". Davis Vanguard. August 15, 2025. Retrieved August 20, 2025.

- ^ Heath, Thomas. "GERRY SPENCE, ATTORNEY AT LORE". Washington Post. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ Spence, Gerry (1983). Of Murder and Madness: A True Story. Doubleday. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-385-18801-2.

- ^ a b "Gerry Spence keynote speaker page at the Harry Walker Agency Speakers Bureau". Archived from the original on March 4, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Fringe-wearing Wyoming trial lawyer Gerry Spence dies at 96". AP News.

- ^ Spence, Gerry (November 11, 2016). "Fighting for the People | Gerry Spence | TEDxJacksonHole". TedX. Retrieved July 12, 2022 – via YouTube.

- ^ a b McFarland, Clair (August 14, 2025). "Gerry Spence, Famed Defense Attorney And Wyoming Native, Dies At 96". Cowboy State Daily. Retrieved August 14, 2025.

- ^ a b Silkwood Case Laid To Rest, August 30, 1986, Science News.

- ^ a b "Karen Silkwood's sudden death unpacked in ABC documentary". ABC News.

- ^ Winter, Bill (1980). "Career Criminal Laws Under the Gun". American Bar Association Journal. 66 (6): 707–708. ISSN 0002-7596. JSTOR 20746569.

- ^ Goodman, Walter (March 14, 1984). "BOOKS OF THE TIMES". Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Rempel, William C. (April 17, 1990). "COLUMN ONE : Champion of the Legal Lost Cause : Gerry Spence made his reputation taking on 'unwinnable' cases. Defending Imelda Marcos may be his biggest gamble yet". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "A new book brings back courtroom memories". National Law Journal. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Cole, Dana (January 1, 2004). "Gerry Spence's The Smoking Gun As A Teaching Tool". Akron Law Faculty Publications.

- ^ Snook, Edward (July 28, 2007). "Grants Pass City Attorney Ulys Stapleton "Take the Kid Out"". US Observer. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ "Oregon State Bar Bulletin — AUGUST 2012". www.osbar.org. 2012. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Spence, Gerry (1994). From Freedom to Slavery: The Rebirth of Freedom in America. St. Martin's Press.

- ^ Ivins, Molly (December 1, 1979). "Wyoming Jury Frees Law Official in Killing Knight of Old West Presented". The New York Times.

- ^ "Quickdraw lawman Ed Cantrell dies". June 14, 2004.

- ^ Lacey, Michael (June 19, 1991). "Of firebrands and files". Phoenix New Times. Archived from the original on June 17, 2011.

- ^ "Ice Cream Maker Wins Suit on Oral Contract", Associated Press, The New York Times, January 22, 1984.

- ^ Chris Merrill, "In new 'retirement', Wyoming's most famous attorney laments 'demonizing' of trial lawyers", Star-Tribune Casper Wyoming, December 21, 2008.

- ^ Zoglin, Richard (December 1, 1986). "Video: What If Oswald Had Stood Trial?". Time.

- ^ THE PROSECUTION OF GEORGE W. BUSH FOR MURDER: ABOUT THE AUTHOR Archived August 28, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Mystery Writers of America Announces the 2008 Edgar Award Winners" (Press release). May 1, 2008. Archived from the original on April 29, 2009. Retrieved May 2, 2009.

- ^ Bugliosi, Vincent (2007). Reclaiming History (1st ed). New York: W.W. Norton & Co. ISBN 978-0-393-04525-3

- ^ Daryl L. Hunter, "Tort Reform", Greater Yellowstone Resource Guide, June 2006. Supporters of Amendment D cited Spence as spearheading its defeat.

- ^ "Gerry Spence Biography at Trial Lawyers College". Archived from the original on June 6, 2008. Retrieved August 22, 2008.

- ^ "Trial Lawyers College Mission Statement". Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ "Spence's No Loss Record Stands With Fieger Acquittal", ABA Journal.

- ^ "Wyoming Personal Injury Lawyers, The Spence Law Firm". Spencelawyers.com. Retrieved December 6, 2015.

- ^ "Iowa wrongful imprisonment case ends in mistrial". Twin Cities. December 14, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2023.

- ^ "Wrongful conviction lawsuit settled, sealed | the des Moines Register…". The Des Moines Register. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013.

- ^ "Gerald L. Spence". Super Lawyers. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ^ "2008 Award Recipients". www.caoc.org. 2008. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ "Gerry L. Spence | The Spence Law Firm, LLC". www.spencelawyers.com. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ LLC, The Spence Law Firm (August 2, 2013). "Gerry Spence Honored with AAJ Lifetime Achievement Award". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ "Lifetime Achievement Award". www.justice.org. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

- ^ Spence, Gerry. "Gerry Spence Method". gerryspencemethod.com/. Retrieved July 12, 2022.

- ^ "A Conversation With Gerry Spence". Wyoming Lawyer Magazine. 2022. Retrieved November 28, 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Mead, Jean Henry (1981). Wyoming in Profile. Boulder, Colorado: Pruett Publishing Company. pp. 308–313. ISBN 978-0-87108-600-6. LCCN 82-12230. OCLC 8588031. Retrieved August 20, 2025.

External links

[edit]- Gerry Spence's official website

- Gerry Spence's Blog

- SpenceLawyers.com

- Gerry Spence at IMDb

- Gerry Spence Quotes

- "Spence: $2M settlement underscores loss of freedom"

- Lust for Justice: The Radical Life & Law of J. Tony Serra, October 22, 2010, by courtroom artist Paulette Frankl, foreword by Gerry Spence

Gerry Spence

View on GrokipediaEarly Life and Education

Childhood and Family Background

Gerald Leonard Spence was born on January 8, 1929, in Laramie, Wyoming, the eldest of three children to Gerald M. Spence, a chemist who worked various jobs including as a rail tie inspector, and Esther (Pfleeger) Spence, a homemaker.[6][7] The family soon relocated to Sheridan, where Spence spent much of his early years amid the sparse, self-reliant rhythms of small-town Wyoming life.[1] During the Great Depression, the Spences endured economic hardship but maintained solvency through frugality and resourcefulness, including renting rooms to boarders and drawing on his father's hunting skills—such as using elk hides for clothing sewn by his mother.[8][1] Esther Spence, devoutly Christian, extended aid to transients like hobos passing through, underscoring the era's communal yet precarious survival amid widespread institutional failures.[9] These experiences in Depression-era Wyoming instilled in young Spence an early appreciation for individual resilience and wariness of distant economic powers.[1] Frontier influences and limited formal resources shaped Spence's initial exposure to oral traditions and persuasive expression, fostering a worldview rooted in personal agency over reliance on external structures.[3]Legal Training and Early Influences

Gerald Leonard Spence completed his undergraduate studies at the University of Wyoming in 1949 before enrolling in the University of Wyoming College of Law.[6] There, he excelled academically, graduating first in his class in 1952.[1] His legal training emphasized practical application suited to Wyoming's rural context, where disputes often involved local ranchers, farmers, and small communities rather than abstract corporate or urban litigation.[4] Despite his top ranking, Spence failed the Wyoming bar examination on his initial attempt, a setback he later attributed to the exam's disconnect from real-world advocacy skills.[10] He passed on the second try and was admitted to the Wyoming bar in 1952, marking his entry into practice amid the state's sparse legal infrastructure.[11] This early hurdle underscored the challenges of transitioning from academic rigor to the demands of frontier-style justice, where persuasive storytelling and jury connection prevailed over procedural formalism.[12] Spence's formative years in law school and immediate post-graduation period exposed him to mentors and peers who prioritized oral advocacy and client-centered representation, fostering a disdain for bureaucratic legalism in favor of combative, narrative-driven courtroom tactics.[13] These influences, drawn from Wyoming's insular legal circles, instilled a worldview that viewed law as a tool for empowering the underrepresented against distant powers, setting the stage for his adversarial style.[14]Early Legal Career

Prosecutorial Roles

Spence began his prosecutorial career shortly after graduating from the University of Wyoming College of Law in 1952, entering private practice in Riverton before being elected prosecuting attorney for Fremont County, Wyoming, in 1954 at the age of 25, making him the youngest county prosecutor in the state at the time.[15] [16] He served in this role until 1962, managing a docket of criminal cases typical of a rural jurisdiction, including felonies and misdemeanors arising from community disputes and everyday offenses.[6] During this period, Spence honed his courtroom techniques, emphasizing rigorous cross-examination and the strategic presentation of evidence to construct compelling narratives for juries.[3] Spence reportedly secured convictions in all criminal jury trials he prosecuted, contributing to his early reputation for unrelenting pursuit of justice against defendants in local matters.[1] This undefeated record as a prosecutor underscored his tenacity, as he aggressively advocated for the state's interests in trials where outcomes hinged on persuading rural juries through direct, persuasive argumentation rather than reliance on institutional resources.[17] His approach during these years laid foundational skills that he later attributed to mastering the adversarial dynamics of litigation from the prosecution's vantage.[3] A notable extension of his prosecutorial experience came in 1979 when Spence was appointed special prosecutor in the murder trial of Mark Hopkinson in Sweetwater County, Wyoming, a case involving bombings and killings linked to a locally influential figure's attempts to intimidate witnesses and eliminate rivals.[18] Facing death threats, Spence wore a bulletproof vest and employed bodyguards in court, yet secured a conviction for Hopkinson, who was sentenced to death for orchestrating multiple murders.[6] This high-stakes prosecution highlighted his willingness to confront entrenched local power structures aggressively, an encounter that reportedly shaped his subsequent skepticism toward institutional overreach and abuses of authority in the justice system.[18]Transition to Private Practice

After serving as Fremont County prosecutor from 1954 to 1962, Gerry Spence returned to private practice in Wyoming, initially continuing his representation of insurance companies and corporations in defense matters, including personal injury and property disputes.[19][6] This phase, spanning roughly the first 18 years of his career from 1952 onward, yielded numerous victories for corporate clients, establishing his reputation as a formidable trial attorney.[20] However, Spence later expressed disillusionment with the constraints of prosecutorial roles, where systemic limitations hindered advocacy for individual claimants, prompting his full commitment to private litigation.[3] In private practice, Spence encountered insurers' routine use of delay tactics and resource imbalances that disadvantaged plaintiffs, insights gained from defending such entities which fueled his shift toward plaintiff-side representation by the late 1960s.[16][21] Early successes against insurers in this new orientation highlighted these patterns, reinforcing his resolve to challenge established powers on behalf of under-resourced clients unable to afford upfront fees.[1] He adopted contingency fee arrangements, aligning financial incentives with outcomes for individuals pursuing claims against corporations.[3] During the 1960s, Spence founded what became the Spence Law Firm, basing operations initially in central Wyoming before relocating to Jackson in 1978, with a practice emphasizing civil disputes where power asymmetries disadvantaged ordinary litigants.[3] This evolution marked a departure from defense work, driven by a recognition that prosecutorial and early private roles often perpetuated institutional barriers to justice for the vulnerable.[22]Major Civil Litigation

Karen Silkwood Case

In 1974, Karen Silkwood, a technician at Kerr-McGee's Cimarron plutonium fuels plant in Oklahoma, became internally contaminated with plutonium, an incident uncontested as occurring off-site at her apartment approximately 20 miles from the facility.[23] Gerry Spence led the legal team representing her estate in a federal negligence suit against Kerr-McGee, filed after Silkwood's death in a single-car crash on November 13, 1974, while en route to meet a New York Times reporter with documents alleging plant safety violations.[24] The suit focused on empirical evidence of Silkwood's contamination—traced via urine, feces, and tissue samples to plant-sourced plutonium—and Kerr-McGee's failure to prevent breaches in handling protocols, including inadequate record-keeping and monitoring of radioactive materials.[25] During the 1979 trial in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Oklahoma, Spence emphasized causation rooted in verifiable plant practices rather than regulatory compliance claims, presenting testimony from experts like Dr. John Gofman on the health risks of plutonium ingestion and inhalation, and evidence of prior contamination incidents at the facility.[24] The defense argued Silkwood's actions, such as possible self-contamination amid union activities, absolved the company, but the jury rejected this, finding Kerr-McGee negligent in allowing off-site plutonium dispersal.[23] After 21 hours of deliberation, the jury awarded the estate $505,000 in compensatory damages for personal injury and $10 million in punitive damages, totaling $10.5 million, signaling jury recognition of willful safety lapses over official attributions of isolated error.[26][1] Kerr-McGee appealed, leading to reversals on evidentiary grounds and punitive damage caps, though the U.S. Supreme Court in 1984 upheld application of state punitive remedies despite federal nuclear regulation preemption.[27] Prolonged litigation, marked by disputes over contamination sourcing absent direct proof of intentional misconduct by Kerr-McGee agents, culminated in an August 1986 out-of-court settlement of $1.38 million to the estate, with the company admitting no liability and the funds divided among family members and attorneys.[28][29] This outcome underscored tensions between jury assessments of empirical harm and appellate deference to institutional defenses in corporate negligence claims.[24]Other High-Value Verdicts Against Corporations

In 1992, Spence secured a $33.5 million verdict, including punitive damages, on behalf of a quadriplegic client whose insurer had refused to honor a $50,000 policy despite clear coverage, deliberately delaying payments and exacerbating the client's emotional distress through bad-faith tactics designed to minimize payouts. The jury awarded substantial punitives to deter such corporate practices, where internal claims-handling documents revealed systematic denial strategies prioritizing profits over policyholders' verifiable needs, directly linking the insurer's conduct to prolonged suffering.[4] Spence also obtained multimillion-dollar verdicts in product liability cases against manufacturers of unsafe vehicles and industrial equipment, where evidence from corporate internal records demonstrated prior knowledge of design defects that foreseeably caused severe injuries, such as paralysis or fatalities, without adequate warnings or recalls.[30] These outcomes highlighted causal chains from concealed risks to individual harms, with juries imposing liability for failures to act on engineering data that could have prevented accidents.[3] A notable example included a $52 million verdict against McDonald's Corporation for breaching a verbal agreement with a small ice-cream supplier, where the fast-food chain's abandonment of the deal led to the supplier's bankruptcy and financial ruin, underscoring corporate leverage over vulnerable partners.[4] Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, Spence maintained an undefeated streak in civil trials between major verdicts, leveraging narrative techniques to convey human impacts over rote legal arguments, enabling juries to grasp the direct consequences of institutional decisions.[6][2]Criminal Defense Cases

Imelda Marcos Trial

In 1990, Gerry Spence led the defense of Imelda Marcos, widow of former Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, in a high-profile federal trial in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Marcos and Saudi financier Adnan Khashoggi were charged with racketeering, fraud, and conspiracy for allegedly embezzling more than $200 million from the Philippine national treasury during Ferdinand Marcos's regime and laundering the funds into U.S. investments, including four Manhattan real estate properties, artwork, and jewelry.[31] The indictment, filed in 1988 after the couple's 1986 exile following the People Power Revolution, reflected U.S. efforts to recover assets amid shifting diplomatic relations with the post-Marcos Philippine government.[31] The trial, presided over by Judge John F. Keenan, spanned three months starting in April 1990 and involved the prosecution presenting testimony from 95 witnesses and extensive financial records purporting to trace illicit transfers. Spence employed an aggressive cross-examination strategy, questioning the provenance of government-linked funds and portraying any Philippine investments in U.S. assets as legitimate state activities rather than personal theft.[32] He humanized Marcos as a culturally sheltered widow lacking knowledge of complex financial schemes orchestrated by others, opting not to call defense witnesses or present a formal case-in-chief, instead relying on summation to cast doubt on her direct involvement and the prosecution's narrative of personal enrichment.[3] Spence's folksy, theatrical style—marked by emotional appeals and cowboy attire—drew sharp rebukes from Keenan, who interrupted proceedings multiple times to warn that such tactics risked prejudicing the jury against his client.[33] After five days of deliberations, the jury acquitted Marcos and Khashoggi on all six counts on July 2, 1990—coinciding with Marcos's 61st birthday—citing insufficient evidence of her culpability and skepticism over U.S. jurisdiction for acts primarily occurring abroad.[31] Jurors later noted Spence's effectiveness in reframing Marcos as a sympathetic figure amid a politically inflected case, though the verdict did not preclude ongoing civil forfeiture proceedings against Marcos family assets.[3] The outcome highlighted Spence's advocacy for robust due process in defending polarizing clients, using the platform to probe potential overreach in prosecutions linked to international regime changes.[34]Randy Weaver and Ruby Ridge Defense

Gerry Spence represented Randy Weaver pro bono in the 1993 federal trial stemming from the Ruby Ridge standoff, a 10-day siege from August 21 to 31, 1992, at the Weaver family's remote cabin near Naples, Idaho, during which U.S. marshals, ATF agents, and FBI personnel engaged Weaver and associate Kevin Harris, resulting in the deaths of Weaver's 14-year-old son Sammy, his wife Vicki (who was unarmed and holding their infant daughter), and Deputy Marshal William Degan.[35] Spence, who disagreed with Weaver's expressed white separatist views but viewed the case as a defense against federal overreach, framed the proceedings as a violation of Weaver's rights to religious freedom, self-defense, and protection from entrapment and unconstitutional force.[36][35] Central to Spence's strategy was evidence of ATF entrapment, where informant Kenneth Fadeley befriended Weaver at Aryan Nations gatherings and induced him to modify sawed-off shotguns in violation of federal law, setting the pretext for Weaver's initial indictment and subsequent failure to appear after a court date adjustment he claimed not to receive.[37] Spence further contended that FBI tactics escalated the confrontation unnecessarily, including the initial shooting of the family dog on August 21—which provoked return fire killing Degan—and the adoption on August 22 of revised rules of engagement authorizing snipers to use deadly force against any armed adult male observed outside the cabin, even absent an immediate threat or surrender demand, a policy that deviated from standard FBI deadly force protocols requiring objective reasonableness.[35][38] This culminated in FBI sniper Lon Horiuchi's August 22 shots, which wounded Weaver and killed Vicki Weaver through a cabin door, actions Spence portrayed as empirical evidence of federal recklessness bordering on a police-state disregard for due process and civilian life.[35][38] The trial, held in Boise before U.S. District Judge Edward Lodge from April 12 to July 8, 1993, saw Weaver charged with first-degree murder in Degan's death, assault on federal officers, conspiracy, and firearms violations; Harris faced similar counts including murder.[35] The jury acquitted Weaver on all felony charges except the misdemeanor failure to appear, for which he received an 18-month sentence (with credit for 14 months pre-trial detention) and a $10,000 fine, and acquitted Harris entirely, rejecting the government's narrative and implicitly validating Spence's claims of entrapment and excessive force.[35] Spence's defense exposed systemic flaws in federal operations, prompting a 1994 Department of Justice task force report that deemed the FBI's rules of engagement unconstitutional and the fatal second shot unjustified, alongside congressional hearings that criticized agency cover-ups and policy deviations.[38] These revelations contributed to government settlements, including $3.1 million to the Weaver family for Vicki and Sammy's wrongful deaths in 1995, underscoring judicial affirmation of individual rights against escalatory federal tactics despite Weaver's partial conviction on procedural grounds.[35][40]Additional Notable Defenses

In 1986, Spence defended Lee Harvey Oswald in a televised, unscripted mock trial produced by London Weekend Television and aired on Showtime, reenacting the assassination of President John F. Kennedy with a real British judge, American jurors, and surviving witnesses.[41] Prosecuting attorney Vincent Bugliosi presented evidence supporting the Warren Commission's conclusion of Oswald's guilt, while Spence highlighted inconsistencies, suppressed evidence, and investigative shortcomings to argue reasonable doubt, resulting in the jury's acquittal of Oswald on all charges.[20] This representation underscored Spence's pattern of contesting official narratives in criminal proceedings without affirming the client's ideology, focusing instead on evidentiary and procedural critiques.[42] Spence undertook pro bono defenses in several serious criminal matters, including the 1978 trial of Sandra Jones in Oregon, where she was charged with murdering her husband after years of documented abuse; Spence secured acquittal by emphasizing self-defense claims and challenging the prosecution's narrative of premeditation.[18] His approach in such cases consistently prioritized exposing flaws in law enforcement investigations and statutory applications over debates on factual guilt, often leveraging jury scrutiny of authority to achieve not-guilty verdicts in an undefeated criminal trial record spanning prosecutor and defense roles.[1] This method avoided glorification of defendants' backgrounds, instead targeting systemic overreach in criminal justice processes.[11]Activism and Institutional Contributions

Opposition to Tort Reform

Spence spearheaded opposition to tort reform initiatives in Wyoming during the 2004 election cycle, focusing on two proposed constitutional amendments aimed at capping non-economic damages in medical malpractice cases at $250,000 and restricting contingency fee arrangements for attorneys.[43] These measures, backed by insurance companies, hospitals, and physician lobbies, sought to limit jury awards amid claims of rising malpractice premiums.[43] Spence, self-funding his efforts, crisscrossed the state hosting town hall meetings to mobilize public resistance, ultimately contributing to the defeat of both proposals at the ballot.[9][44] Central to Spence's arguments was the assertion that damage caps insulate negligent actors—particularly physicians and their insurers—from full accountability, allowing them to externalize costs onto victims without sufficient deterrence.[44] He maintained that juries, as representatives of local communities, possess superior insight to determine fair compensation compared to uniform legislative caps, which he characterized as arbitrary interventions favoring corporate interests over individual justice.[44] Spence framed tort reform as "class warfare" driven by insurance conglomerates seeking to safeguard profits, noting that even after such reforms elsewhere, premiums continued to escalate independently of verdict trends.[44] Drawing from his career securing over $300 million in verdicts, many reliant on punitive damages against deep-pocketed defendants, Spence contended that compensatory awards alone routinely under-compensate victims when confronting entities capable of absorbing losses as a cost of business, necessitating punitives to enforce behavioral change and prevent recurrence of harms.[44][45] While acknowledging proponent claims that uncapped verdicts escalate liability insurance costs, encourage defensive medicine, and potentially stifle innovation by heightening corporate risk aversion, Spence prioritized causal accountability, arguing that shielding wrongdoers from proportionate consequences undermines the jury system's role in redressing empirically verifiable injuries.[44][46]Founding of Trial Lawyers College

In 1993, Gerry Spence established the Trial Lawyers College as a nonprofit organization dedicated to training lawyers committed to the jury system and advocating for justice on behalf of ordinary people, particularly the poor, injured, and marginalized.[47] The institution was created at Spence's Thunderhead Ranch in Wyoming, transforming the property into a campus for intensive, experiential trial advocacy programs that prioritized human connection over conventional legal education.[48] Unlike elite bar preparation courses emphasizing procedural rules and abstract theory, the College's curriculum focused on practical skills such as storytelling, empathy-building, and improvisation to foster authentic courtroom presence.[49] Central to the training was the use of psychodrama techniques, which involved dramatic reenactments and peer exercises to uncover participants' personal truths, confront inner biases, and enhance self-awareness—enabling lawyers to better connect with jurors and clients by first understanding their own emotional barriers.[50] Mock trials and on-your-feet practice sessions rejected rote memorization in favor of narrative-driven advocacy, teaching participants to reveal the human story behind cases rather than relying on gamesmanship or technical maneuvers.[51] This approach aimed to equip attorneys, including many public defenders and those handling indigent representation, with tools for empathetic listening and credible persuasion, shifting trial practice toward realism rooted in lived experience over detached proceduralism.[52] Over its initial decades, the College influenced thousands of lawyers by producing graduates who applied these methods in real-world litigation, emphasizing causal storytelling to counter corporate or institutional narratives in court.[53] The program's emphasis on revealing subconscious influences through psychodrama distinguished it from standard advocacy seminars, promoting a warrior-like authenticity in representation that Spence viewed as essential for effective jury trials.[54]Broader Advocacy on Justice System Reform

Spence critiqued the American justice system for enabling a "police state" through doctrines like qualified immunity, which he argued insulates law enforcement from civil liability for constitutional violations, and the increasing militarization of police departments with military-grade equipment post-1990s federal grants.[55][56] In his 2015 book Police State: How America's Cops Get Away with Murder, Spence detailed how these factors contribute to unchecked police violence, citing the 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff—where he represented defendant Randy Weaver—as a case exemplifying federal agents' excessive force and evasion of accountability despite killing Weaver's wife and son.[57] While emphasizing the necessity of policing for public order, Spence maintained that without rigorous oversight, such protections erode individual rights and foster authoritarianism, drawing on empirical patterns of unreported officer misconduct revealed in civil suits he litigated.[55] In broader writings, Spence advocated empowering juries as the core mechanism for truth-finding in adversarial proceedings, arguing that judges and prosecutors undermine this by prioritizing procedural efficiencies over lay fact-finders' intuitive judgments.[58] He opposed coercive plea bargaining, which by the 1980s accounted for over 90% of criminal convictions, contending it pressures defendants—often indigent and unrepresented—into waiving trials to avoid harsher sentences, thus subverting the system's foundational presumption of innocence and jury role.[59] Grounded in the principle that genuine justice emerges from contested evidence rather than coerced admissions, Spence proposed reforms like mandatory jury involvement in sentencing and limits on prosecutorial leverage to restore balance.[60] Spence also defended Second Amendment rights and rural property protections in his speeches and books, countering urban-focused reforms that overlook self-reliance in isolated areas.[61] As a Wyoming resident with ranching experience, he argued that gun ownership enables necessary defense against wildlife, intruders, and government intrusion in remote contexts, where police response times average over an hour, citing data from federal rural crime statistics to underscore the causal link between disarmament and vulnerability.[61] These positions framed property rights not as absolute but as essential bulwarks against centralized overreach, informed by cases like Weaver's where land-use disputes escalated due to regulatory enforcement.[56]Media Presence and Authorship

Television and Public Speaking

Spence appeared on national television programs such as 60 Minutes, Larry King Live, The Oprah Winfrey Show, and Geraldo, leveraging these platforms to articulate unscripted critiques of the justice system and case strategies drawn from his trial experience.[62][1] During the O.J. Simpson trial in 1995, he served as a legal consultant for NBC, offering real-time analysis of evidentiary disputes and procedural maneuvers broadcast to viewers.[4] In formats like the 1997 mock trial series Trial and Error, Spence adopted his signature fringe jacket to deliver arguments that emphasized personal narratives over abstract legal theory, aiming to evoke empathy and clarify the human stakes in disputes.[63] Beyond broadcast media, Spence conducted public lectures at law schools and bar associations, focusing on practical advocacy techniques such as authentic juror engagement during voir dire, as in his 1986 address to the Texas Trial Lawyers Association and South Texas College of Law.[64] His seminar-style talks, including the widely circulated "Be Who You Are," stressed the advocate's need for emotional vulnerability to forge genuine connections, rejecting polished performances in favor of raw, experiential dialogue that mirrored courtroom improvisation.[65] These sessions, often held at venues like Thunderhead Ranch or professional conferences, prioritized storytelling rooted in first-hand case realities over rehearsed debates, positioning public discourse as an extension of trial advocacy's core imperatives.[66] In congressional testimony, such as his 1994 appearance before a U.S. Senate committee aired on C-SPAN, Spence advocated for systemic reforms by linking procedural flaws to broader erosions of individual rights.[67]Key Publications and Writings

Gunning for Justice (1982), Spence's debut book, chronicles his evolution from an insurance defense attorney to a champion of underdogs, exposing idealized myths of frontier justice in the American West as incompatible with systemic power imbalances that favor institutions over individuals.[68] The narrative underscores how legal outcomes hinge on underlying causal forces like economic leverage rather than abstract ideals of fairness.[69] In With Justice for None: Destroying an American Myth (1989), Spence dissects the commodification of lawyers within a justice system where verdicts reflect wealth disparities, with the affluent evading accountability while the impoverished face punitive measures, based on his observations of court dynamics and proposing structural reforms to prioritize empirical accountability over procedural rituals.[60] He challenges media narratives labeling lawsuits as "frivolous," arguing such distortions obscure causal realities of corporate malfeasance and judicial deference to power, drawing from decades of trial experience to advocate scrutiny of verdict drivers beyond surface-level reporting.[59] Spence's later works extend this critique to law enforcement, as in Police State: How America's Cops Get Away with Murder (2015), where he catalogs instances of officer impunity, attributing outcomes to institutionalized protections that shield abuses through qualified immunity and narrative control, rather than rigorous causal investigation of incidents.[70] He calls for empirical dissection of police encounters—analyzing precipitating factors, training failures, and accountability gaps—over reflexive trust in official accounts, positioning such realism as essential to dismantling tyrannical tendencies in policing.[71] These publications collectively frame law as a battleground of power asymmetries, where truth emerges from first-hand causal reasoning, not deference to authority or mediated myths.Personal Life and Public Persona

Ranch Life and Distinctive Style

Gerry Spence owned Thunderhead Ranch, a expansive property spanning approximately 70,000 acres near Dubois, Wyoming, which he transformed from a working cattle operation into a personal retreat and training ground reflective of his rooted, independent lifestyle.[48] The ranch, acquired prior to the 1990s when much of it was sold to the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, symbolized Spence's embrace of self-reliance amid Wyoming's harsh landscape, where he ran cattle and distanced himself from urban legal circles.[72] This setting underscored his ethos of authenticity, as he described himself as a genuine cowboy managing a substantial ranch operation.[73] In courtroom appearances, Spence rejected traditional business suits for buckskin-fringed jackets, often hand-sewn from local hides, paired with cowboy boots, snakeskin elements, and a white Stetson hat.[1] [6] This attire, which drew initial ridicule from court officials and peers, served as an intentional signal of relatability to juries, portraying him as a straightforward country lawyer rather than an elitist professional.[74] [75] His ranch-based existence, insulated from coastal influences, cultivated the focused mindset he deemed vital for persuasive advocacy, emphasizing personal truth and narrative over detached analysis.[58]Family and Relationships

Spence married Anna Fidelia Wilson on June 20, 1948, and they had four children: Katy Ann Spence, Kip Tyler Spence, Kerry Spence, and Kent Spence.[76][19] The couple divorced in 1969.[6] In 1970, he married LaNelle Hampton Peterson, whom he affectionately called "Imaging" after a dream-inspired vision, and they remained wed for 57 years, dividing their time between homes in Dubois, Wyoming, and Santa Barbara, California.[76][77][1] LaNelle Spence handcrafted Spence's signature buckskin coat, which became emblematic of his courtroom persona, reflecting the couple's shared commitment to his professional image amid a nomadic trial schedule.[1] The marriage also brought two stepchildren, Brents Hawks and Christopher Hawks.[19] Spence maintained a relatively private family life despite his public profile, with his children and extended family—including 13 grandchildren and one great-grandchild—providing continuity amid the demands of high-stakes litigation.[19][78] In his later years of semi-retirement, Spence prioritized time with family, including grandchildren, while sustaining the close-knit support that underpinned his endurance through protracted trials.[3][79] No major personal scandals emerged publicly, underscoring the stability of his relationships relative to his flamboyant professional life.[6][80]Controversies and Criticisms

Ethical Questions in Client Selection

Spence's pro bono representation of Randy Weaver, a white separatist involved in the 1992 Ruby Ridge standoff, exemplified his commitment to defending clients regardless of their political or ideological views, emphasizing the principle that every accused deserves zealous advocacy to test the justice system's integrity.[56] In a letter to a colleague urging withdrawal due to Weaver's extremist associations, Spence argued that declining such cases would erode due process for all, stating he would defend Weaver's right to a fair trial without endorsing his beliefs, as the real issue was potential government overreach rather than the client's politics.[81] This stance drew implicit criticism from those who viewed it as legitimizing radical elements, potentially associating the defense bar with harmful ideologies, though no formal bar complaints materialized, consistent with ethical rules prohibiting refusal of representation based solely on a client's opinions or associations absent illegal conduct. Similarly, Spence's paid defense of Imelda Marcos in her 1990 New York racketeering trial, where she faced charges of embezzling over $200 million from the Philippines, raised questions about the moral boundaries of client selection, as critics questioned whether advocating for a figure linked to authoritarian excess compromised professional integrity or public perception of the bar.[32] Spence maintained that lawyers must confront systemic prosecutorial flaws—such as evidentiary overreach—without preemptively judging clients' past actions, prioritizing causal accountability in trials over personal moral vetting, which he saw as a slippery slope toward selective justice.[1] Opponents argued this approach risked "associational harms," where high-profile acquittals (Marcos was cleared on all counts) could be perceived as tacit endorsement of client conduct, potentially undermining trust in legal advocacy amid biases in media portrayals favoring narrative over procedural rigor.[82] Empirically, Spence's defenses yielded exposures of institutional biases that arguably outweighed ideological risks: the Weaver trial contributed to a 1995 U.S. Department of Justice report condemning FBI rules of engagement as unconstitutional, prompting a $3.1 million settlement with the family and reforms in federal tactics, demonstrating how unpopular representations can catalyze accountability without requiring lawyer alignment with client extremism.[1] In Marcos's case, while less transformative, the acquittal highlighted prosecutorial reliance on circumstantial evidence from politically charged sources, underscoring Spence's thesis that adversarial testing reveals flaws in accusations derived from regime change narratives rather than irrefutable proof.[33] These outcomes supported his first-principles view that ethical lawyering demands universal due process to preserve systemic realism, countering critiques that such selections enable radicals by instead revealing causal prosecutorial incentives over genuine justice.[56]Professional and Stylistic Critiques

Spence's courtroom theatrics, including his signature buckskin attire and storytelling techniques, drew sharp rebukes from rival attorneys who accused him of favoring emotional manipulation over substantive evidence presentation. Fellow lawyers reportedly dismissed him as a "phony bastard" and "charlatan," viewing his flamboyant style as undermining the profession's integrity by prioritizing jury persuasion through spectacle rather than rigorous legal argumentation.[1][83] Several of Spence's high-profile verdicts faced appellate scrutiny for alleged excessiveness, particularly punitive damages awards that critics argued inflated claims beyond compensatory needs. In cases like the Karen Silkwood litigation against Kerr-McGee, where Spence secured a $10.5 million verdict including substantial punitives in 1979, appeals challenged the awards as disproportionate, contributing to broader debates on "jackpot justice."[84][85] Such outcomes positioned Spence as a symbol for tort reform advocates, who cited his successes as exemplifying unchecked plaintiff tactics that drove up liability costs and prompted legislative caps on damages.[86] While defenders highlighted Spence's claimed undefeated record in over 300 jury trials as validation of his methods' effectiveness in securing justice for underdogs, detractors contended that this streak masked a reliance on performative elements that overshadowed factual substance, potentially misleading juries on case merits.[2] Spence rebutted tort reform initiatives by emphasizing empirical gaps in accountability, arguing in public campaigns that corporate harms often evaded punishment without robust damage awards to deter misconduct.[44][9]Legacy and Death

Impact on Trial Advocacy

Spence's establishment of the Trial Lawyers College in 1994 introduced a training paradigm centered on psychodrama, authentic self-expression, and client narrative reconstruction, which has educated thousands of attorneys in persuasion techniques that prioritize emotional resonance over formulaic argumentation.[20][53] This methodology democratized trial skills by making them accessible to practitioners outside Ivy League or corporate legal pipelines, emphasizing the lawyer's role in amplifying ordinary clients' stories to counter institutional power imbalances in courtrooms.[58][87] His courtroom successes further propagated these principles, as multimillion-dollar verdicts like the $10 million punitive award in the 1979 Silkwood case—upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1984—demonstrated the potency of narrative-driven advocacy in securing deterrence against corporate negligence, setting a precedent for state-law punitive remedies in federally regulated industries.[88] Similarly, the 1992 bad-faith insurance verdict yielding $15 million in emotional damages and $18.5 million in punitives for a quadriplegic client reinforced accountability standards, influencing subsequent cases by highlighting the jury's capacity to impose substantial penalties for willful claim denials.[4] These outcomes inspired broader skepticism of unassailable expert testimony, advocating instead for cross-examinations that expose biases and restore focus to lived human impacts.[2] Critics have faulted Spence's techniques for fostering adversarial overreach, such as aggressive maneuvers that test judicial boundaries and prioritize theatricality, potentially undermining procedural fairness.[89] Nonetheless, proponents attribute to him a pivotal role in safeguarding jury autonomy amid rising procedural hurdles like summary judgments and Daubert gatekeeping, which threaten to diminish lay fact-finders' influence in favor of judicial or expert filters.[90] By modeling unrelenting jury appeals, Spence's legacy endures in sustaining trial advocacy's democratic ethos against encroachments that favor efficiency over comprehensive truth-seeking.[20]Death and Final Years

In his later years, Gerry Spence transitioned to semi-retirement, dividing his time between properties in Wyoming and California while gradually reducing active courtroom involvement.[6] He sold his Jackson Hole residence approximately four years prior to his death and shifted focus toward writing, mentoring, and occasional public engagements, maintaining productivity into his mid-90s.[19] The Spence Law Firm, which he founded, continued operations under successors who handled primary casework.[3] Spence died on August 13, 2025, at age 96 in his Montecito, California, home, surrounded by family members.[19][78] The specific cause was not publicly released, aligning with circumstances typical of advanced age rather than acute illness.[6] His passing prompted reflections on his enduring stylistic impact on trial practice, including critiques of how his performative approaches may have contributed to trends in elevated damage awards, though such effects remain debated among legal observers.[91]References

- https://www.[encyclopedia.com](/page/Encyclopedia.com)/law/law-magazines/randy-weaver-trial-1993