Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Cattle

View on Wikipedia

| Cattle | |

|---|---|

| |

| A brown Swiss Fleckvieh cow wearing a cowbell | |

Domesticated

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Bovinae |

| Genus: | Bos |

| Species: | B. taurus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bos taurus | |

| |

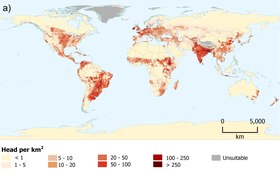

| Bovine distribution | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Cattle (Bos taurus) are large, domesticated, bovid ungulates widely kept as livestock. They are prominent modern members of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus Bos. Mature female cattle are called cows and mature male cattle are bulls. Young female cattle are called heifers, young male cattle are bullocks, and castrated male cattle are known as oxen or steers.

Cattle are commonly raised for meat, for dairy products, and for leather. As draft animals, they pull carts and farm implements. Cattle are considered sacred animals within Hinduism, and it is illegal to kill them in some Indian states. Small breeds such as the miniature Zebu are kept as pets.

Taurine cattle are widely distributed across Europe and temperate areas of Asia, the Americas, and Australia. Zebus are found mainly in India and tropical areas of Asia, America, and Australia. Sanga cattle are found primarily in sub-Saharan Africa. These types, sometimes classified as separate species or subspecies, are further divided into over 1,000 recognized breeds.

Around 10,500 years ago, taurine cattle were domesticated from wild aurochs progenitors in central Anatolia, the Levant and Western Iran. A separate domestication event occurred in the Indian subcontinent, which gave rise to zebu. There were over 940 million cattle in the world by 2022. Cattle are responsible for around 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions. They were one of the first domesticated animals to have a fully-mapped genome.

Etymology

[edit]The term cattle was borrowed from Anglo-Norman catel (replacing native Old English terms like kine, now considered archaic, poetic, or dialectal),[1] itself from Medieval Latin capitāle 'principal sum of money, capital', itself derived in turn from Latin caput 'head'. Cattle originally meant movable personal property, especially livestock of any kind, as opposed to real property (the land, which also included wild or small free-roaming animals such as chickens—they were sold as part of the land).[2] The word is a variant of chattel (a unit of personal property) and closely related to capital in the economic sense.[3][2] The word cow came via Old English cū (plural cȳ), from Proto-Indo-European *gʷṓws (genitive *gʷéws) 'a bovine animal', cf. Persian: gâv, Sanskrit: gó.[4] In older English sources such as the King James Version of the Bible, cattle often means livestock, as opposed to deer, which are wild.[2]

Characteristics

[edit]Description

[edit]Cattle are large artiodactyls, mammals with cloven hooves, meaning that they walk on two toes, the third and fourth digits. Like all bovid species, they can have horns, which are unbranched and are not shed annually.[5] Coloration varies with breed; common colors are black, white, and red/brown, and some breeds are spotted or have mixed colors.[6] Bulls are larger than cows of the same breed by up to a few hundred kilograms. British Hereford cows, for example, weigh 600–800 kg (1,300–1,800 lb), while the bulls weigh 1,000–1,200 kg (2,200–2,600 lb).[7] Before 1790, beef cattle averaged only 160 kg (350 lb) net. Thereafter, weights climbed steadily.[8][9] Cattle breeds vary widely in size; the tallest and heaviest is the Chianina, where a mature bull may be up to 1.8 m (5 ft 11 in) at the shoulder, and may reach 1,280 kg (2,820 lb) in weight.[10] The natural life of domestic cattle is some 25–30 years. Beef cattle go to slaughter at around 18 months, and dairy cows at about five years.[11]

Digestive system

[edit]

Cattle are ruminants, meaning their digestive system is highly specialized for processing plant material such as grass rich in cellulose, a tough carbohydrate polymer which many animals cannot digest. They do this in symbiosis with micro-organisms – bacteria, fungi, and protozoa – that possess cellulases, enzymes that split cellulose into its constituent sugars. Among the many bacteria that contribute are Fibrobacter succinogenes, Ruminococcus flavefaciens, and Ruminococcus albus. Cellulolytic fungi include several species of Neocallimastix, while the protozoa include the ciliates Eudiplodinium maggie and Ostracodinium album.[13] If the animal's feed changes over time, the composition of this microbiome changes in response.[12]

Cattle have one large stomach with four compartments; the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum. The rumen is the largest compartment and it harbours the most important parts of the microbiome.[12] The reticulum, the smallest compartment, is known as the "honeycomb". The omasum's main function is to absorb water and nutrients from the digestible feed. The abomasum has a similar function to the human stomach.[14]

Cattle regurgitate and re-chew their food in the process of chewing the cud, like most ruminants. While feeding, cows swallow their food without chewing; it goes into the rumen for storage. Later, the food is regurgitated to the mouth, a mouthful at a time, where the cud is chewed by the molars, grinding down the coarse vegetation to small particles. The cud is then swallowed again and further digested by the micro-organisms in the cow's stomach.[14]

Reproduction

[edit]

The gestation period for a cow is about nine months long. The ratio of male to female offspring at birth is approximately 52:48.[15] A cow's udder has two pairs of mammary glands or teats.[16] Farms often use artificial insemination, the artificial deposition of semen in the female's genital tract; this allows farmers to choose from a wide range of bulls to breed their cattle. Estrus too may be artificially induced to facilitate the process.[17] Copulation lasts several seconds and consists of a single pelvic thrust.[18]

Cows seek secluded areas for calving.[19] Semi-wild Highland cattle heifers first give birth at 2 or 3 years of age, and the timing of birth is synchronized with increases in natural food quality. Average calving interval is 391 days, and calving mortality within the first year of life is 5%.[20] Beef calves suckle an average of 5 times per day, spending some 46 minutes suckling. There is a diurnal rhythm in suckling, peaking at roughly 6am, 11:30am, and 7pm.[21] Under natural conditions, calves stay with their mother until weaning at 8 to 11 months. Heifer and bull calves are equally attached to their mothers in the first few months of life.[22]

Cognition

[edit]

Cattle have a variety of cognitive abilities. They can memorize the locations of multiple food sources,[24] and can retain memories for at least 48 days.[25] Young cattle learn more quickly than adults,[26] and calves are capable of discrimination learning,[27] distinguishing familiar and unfamiliar animals,[28] and between humans, using faces and other cues.[29] Calves prefer their own mother's vocalizations to those of an unfamiliar cow.[30] Vocalizations provide information on the age, sex, dominance status and reproductive status of the caller, and may indicate estrus in cows and competitive display in bulls.[31] Cows can categorize images as familiar and unfamiliar individuals.[28] Cloned calves from the same donor form subgroups, suggesting that kin discrimination may be a basis of grouping behaviour.[32] Cattle use visual/brain lateralisation when scanning novel and familiar stimuli.[33] They prefer to view novel stimuli with the left eye (using the right brain hemisphere), but the right eye for familiar stimuli.[34] Individual cattle have also been observed to display different personality traits, such as fearfulness and sociability.[23]

Senses

[edit]Vision is the dominant sense; cattle obtain almost half of their information visually.[35] Being prey animals, cattle evolved to look out for predators almost all around, with eyes that are on the sides of their head rather than the front. This gives them a field of view of 330°, but limits binocular vision (and therefore stereopsis) to some 30° to 50°, compared to 140° in humans.[28] They are dichromatic, like most mammals.[36] Cattle avoid bitter-tasting foods, selecting sweet foods for energy. Their sensitivity to sour-tasting foods helps them to maintain optimal ruminal pH.[35] They seek out salty foods by taste and smell to maintain their electrolyte balance.[37] Their hearing is better than that of horses,[38] but worse at localising sounds than goats, and much worse than dogs or humans.[39] They can distinguish between live and recorded human speech.[40] Olfaction probably plays a large role in their social life, indicating social and reproductive status.[35][41] Cattle can tell when other animals are stressed by smelling the alarm chemicals in their urine.[42] Cattle can be trained to recognise conspecific individuals using olfaction only.[41]

Behavior

[edit]Dominance hierarchy

[edit]

Cattle live in a dominance hierarchy. This is maintained in several ways. Cattle often engage in mock fights where they test each other's strength in a non-aggressive way. Licking is primarily performed by subordinates and received by dominant animals. Mounting is a playful behavior shown by calves of both sexes and by bulls and sometimes by cows in estrus,[43] however, this is not a dominance related behavior as has been found in other species.[20] Dominance-associated aggressiveness does not correlate with rank position, but is closely related to rank distance between individuals.[20] The horns of cattle are used in mate selection. Horned cattle attempt to keep greater distances between themselves and have fewer physical interactions than hornless cattle, resulting in more stable social relationships.[44] In calves, agonistic behavior becomes less frequent as space allowance increases, but not as group size changes, whereas in adults, the number of agonistic encounters increases with group size.[45]

Dominance relationships in semi-wild highland cattle are very firm, with few overt aggressive conflicts: most disputes are settled by agonistic (non-aggressive, competitive) behaviors with no physical contact between opponents, reducing the risk of injury. Dominance status depends on age and sex, with older animals usually dominant to young ones and males dominant to females. Young bulls gain superior dominance status over adult cows when they reach about 2 years of age.[20]

Grazing behavior

[edit]

Cattle eat mixed diets, but prefer to eat approximately 70% clover and 30% grass. This preference has a diurnal pattern, with a stronger preference for clover in the morning, and the proportion of grass increasing towards the evening.[46] When grazing, cattle vary several aspects of their bite, i.e. tongue and jaw movements, depending on characteristics of the plant they are eating. Bite area decreases with the density of the plants but increases with their height. Bite area is determined by the sweep of the tongue; in one study observing 750-kilogram (1,650 lb) steers, bite area reached a maximum of approximately 170 cm2 (30 sq in). Bite depth increases with the height of the plants. By adjusting their behavior, cattle obtain heavier bites in swards that are tall and sparse compared with short, dense swards of equal mass/area.[47] Cattle adjust other aspects of their grazing behavior in relation to the available food; foraging velocity decreases and intake rate increases in areas of abundant palatable forage.[48] Cattle avoid grazing areas contaminated by the faeces of other cattle more strongly than they avoid areas contaminated by sheep,[49] but they do not avoid pasture contaminated by rabbits.[50]

Temperament and emotions

[edit]

In cattle, temperament or behavioral disposition can affect productivity, overall health, and reproduction.[52] Five underlying categories of temperament traits have been proposed: shyness–boldness, exploration–avoidance, activity, aggressiveness, and sociability.[53] There are many indicators of emotion in cattle. Holstein–Friesian heifers that had made clear improvements in a learning experiment had higher heart rates, indicating an emotional reaction to their own learning.[54] After separation from their mothers, Holstein calves react, indicating low mood.[55] Similarly, after hot-iron dehorning, calves react to the post-operative pain.[56] The position of the ears has been used as an indicator of emotional state.[28] Cattle can tell when other cattle are stressed by the chemicals in their urine.[42] Cattle are gregarious, and even short-term isolation causes psychological stress. When heifers are isolated, vocalizations, heart rate and plasma cortisol all increase. When visual contact is re-instated, vocalizations rapidly decline; heart rate decreases more rapidly if the returning cattle are familiar to the previously isolated individual.[57] Mirrors have been used to reduce stress in isolated cattle.[58]

Sleep

[edit]The average sleep time of a domestic cow is about 4 hours a day.[59] Cattle do have a stay apparatus,[60] but do not sleep standing up;[61] they lie down to sleep deeply.[62]

Genetics

[edit]

In 2009, the National Institutes of Health and the US Department of Agriculture reported having mapped the bovine genome.[64] Cattle have some 22,000 genes, of which 80% are shared with humans; they have about 1000 genes that they share with dogs and rodents, but not with humans. Using this bovine "HapMap", researchers can track the differences between breeds that affect meat and milk yields.[65] Early research focused on Hereford genetic sequences; a wider study mapped a further 4.2% of the cattle genome.[63]

Behavioral traits of cattle can be as heritable as some production traits, and often, the two can be related.[66] The heritability of temperament (response to isolation during handling) has been calculated as 0.36 and 0.46 for habituation to handling.[67] Rangeland assessments show that the heritability of aggressiveness in cattle is around 0.36.[68]

Quantitative trait loci have been found for a range of production and behavioral characteristics for both dairy and beef cattle.[69]

Evolution

[edit]Phylogeny

[edit]Cattle have played a key role in human history, having been domesticated since at least the early Neolithic age. Archaeozoological and genetic data indicate that cattle were first domesticated from wild aurochs (Bos primigenius) approximately 10,500 years ago. There were two major areas of domestication: one in central Anatolia, the Levant, and Western Iran, which gave rise to the taurine line, and a second in the area that is now Pakistan, which produced the indicine line.[70] Modern mitochondrial DNA variation indicates the taurine line may have arisen from as few as 80 aurochs tamed in the upper reaches of Mesopotamia near the villages of Çayönü Tepesi, in what is now southeastern Turkey, and Dja'de el-Mughara, in what is now northern Syria.[71]

Although European cattle are largely descended from the taurine lineage, gene flow from African cattle (partially of indicine origin) contributed substantial genomic components to both southern European cattle breeds and their New World descendants.[70] A study on 134 breeds showed that modern taurine cattle originated from Africa, Asia, North and South America, Australia, and Europe.[72] Some researchers have suggested that African taurine cattle are derived from a third independent domestication from the North African aurochs.[70] Whether there have been two or three domestications, European, African, and Asian cattle share much of their genomes, both through their species ancestry and through repeated migrations of livestock and genetic material between species, as shown in the diagram.[73]

Taxonomy

[edit]

Cattle were originally identified as three separate species: Bos taurus, the European or "taurine" cattle (including similar types from Africa and Asia); Bos indicus, the Indicine or "zebu"; and the extinct Bos primigenius, the aurochs. The aurochs is ancestral to both zebu and taurine cattle.[74] They were later reclassified as one species, Bos taurus, with the aurochs (B. t. primigenius), zebu (B. t. indicus), and taurine (B. t. taurus) cattle as subspecies.[75] However, this taxonomy is contentious, and authorities such as the American Society of Mammalogists treat these taxa as separate species.[76][77]

Complicating the matter is the ability of cattle to interbreed with other closely related species. Hybrid individuals and even breeds exist, not only between taurine cattle and zebu (such as the sanga cattle (Bos taurus africanus x Bos indicus), but also between one or both of these and some other members of the genus Bos – yaks (the dzo or yattle[78]), banteng, and gaur. Hybrids such as the beefalo breed can even occur between taurine cattle and either species of bison, leading some authors to consider the latter part of the genus Bos, as well.[79] The hybrid origin of some types may not be obvious – for example, genetic testing of the Dwarf Lulu breed, the only taurine-type cattle in Nepal, found them to be a mix of taurine cattle, zebu, and yak.[80]

The aurochs originally ranged throughout Europe, North Africa, and much of Asia. In historical times, its range became restricted to Europe, and the last known individual died in Mazovia, Poland, around 1627.[81] Breeders have attempted to recreate a similar appearance to that of the aurochs by crossing traditional types of domesticated cattle, producing the Heck breed.[82]

A group of taurine-type cattle exist in Africa; these represent either an independent domestication event or the result of crossing taurines domesticated elsewhere with local aurochs, but they are genetically distinct;[83] some authors name them as a separate subspecies, Bos taurus africanus.[84] The only pure African taurine breeds remaining are the N'Dama, Kuri and some varieties of the West African Shorthorn.[85]

Feral cattle are those that have been allowed to go wild.[86] Feral populations exist in many parts of the world,[87][88] sometimes on small islands.[89] Some, such as Amsterdam Island cattle,[75] Chillingham cattle,[90] and Aleutian wild cattle, have become sufficiently distinct to be described as breeds.[91]

Husbandry

[edit]Practices

[edit]

Cattle are often raised by allowing herds to graze on the grasses of large tracts of rangeland. Raising cattle extensively in this manner allows the use of land that might be unsuitable for growing crops. The most common interactions with cattle involve daily feeding, cleaning and milking. Many routine husbandry practices involve ear tagging, dehorning, loading, medical operations, artificial insemination, vaccinations and hoof care, as well as training for agricultural shows and preparations. Around the world, Fulani husbandry rests on behavioural techniques, whereas in Europe, cattle are controlled primarily by physical means, such as fences.[93] Breeders use cattle husbandry to reduce tuberculosis susceptibility by selective breeding and maintaining herd health to avoid concurrent disease.[94]

In the United States, many cattle are raised intensively, kept in concentrated animal feeding operations, meaning there are at least 700 mature dairy cows or at least 1000 other cattle stabled or confined in a feedlot for "45 days or more in a 12-month period".[92]

-

A Hereford being inspected for ticks. Cattle are often restrained in cattle crushes when given medical attention.

-

Cattle feedlot in New Mexico, United States

Population

[edit]

Historically, the cattle population of Britain rose from 9.8 million in 1878 to 11.7 million in 1908, but beef consumption rose much faster. Britain became the "stud farm of the world" exporting livestock to countries where there were no indigenous cattle. In 1929 80% of the meat trade of the world was products of what were originally English breeds. There were nearly 70 million cattle in the US by the early 1930s.[95]

Cattle have the largest biomass of any animal species on Earth, at roughly 400 million tonnes, followed closely by Antarctic krill at 379 million tonnes and humans at 373 million tonnes.[96] In 2023, the countries with the most cattle were India with 307.5 million (32.6% of the total), Brazil with 194.4 million, and China with 101.5 million, out of a total of 942.6 million in the world.[97]

Economy

[edit]Cattle are kept on farms to produce meat, milk, and leather, and sometimes to pull carts or farm implements.[98]

Meat

[edit]The meat of adult cattle is known as beef, and that of calves as veal. Other body parts are used as food products, including blood, liver, kidney, heart and oxtail. Approximately 300 million cattle, including dairy animals, are slaughtered each year for food.[99] About a quarter of the world's meat comes from cattle.[100] World cattle meat production in 2021 was 72.3 million tons.[101]

-

The Hereford is a widespread beef breed, introduced in the 18th century

-

Australian Droughtmaster cattle on an extensive farm in Queensland, Australia

-

Aberdeen Angus, a popular small breed, here in Austria with a traditional cattle bell

- FAO data for 2021

-

Beef is the third most commonly consumed meat worldwide.

-

Beef (and buffalo meat) production has grown substantially over the recent 60 years.

-

Production of beef worldwide, by country in 2021.

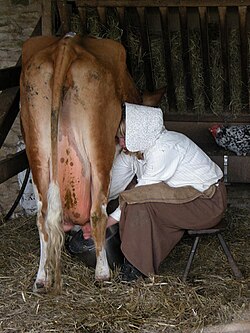

Dairy

[edit]Certain breeds of cattle, such as the Holstein-Friesian, are used to produce milk,[102][103] much of which is processed into dairy products such as butter, cheese, and yogurt. Dairy cattle are usually kept on specialized dairy farms designed for milk production. Most cows are milked twice per day, with milk processed at a dairy, which may be onsite at the farm or the milk may be shipped to a dairy plant for eventual sale of a dairy product.[104] Lactation is induced in heifers and spayed cows by a combination of physical and psychological stimulation, by drugs, or by a combination of those methods.[105] For mother cows to continue producing milk, they give birth to one calf per year. If the calf is male, it is generally slaughtered at a young age to produce veal.[106] Cows produce milk until three weeks before birth.[103] Over the last fifty years, dairy farming has become more intensive to increase the yield of milk produced by each cow. The Holstein-Friesian is the breed of dairy cow most common in the UK, Europe and the United States. It has been bred selectively to produce the highest yields of milk of any cow. The average in the UK is around 22 litres per day.[102][103]

Dairy is a large industry worldwide. In 2023, the 27 European Union countries produced 143 million tons of cow's milk; the United States 104.1 million tons; and India 99.5 million tons.[107] India further produces 94.4 million tons of buffalo milk,[108] making it (in 2023) the world's largest milk producer; its dairy industry employs some 80 million people.[109]

-

Holstein cattle are the primary dairy breed, bred for high milk production.

-

The milking of cattle was once largely by hand. Demonstration at Cogges Manor Farm, Oxfordshire

-

A modern rotary milking parlour, Germany

- FAO data for 2021

-

World production of bovine milk (cow + buffalo)

Draft animals

[edit]

Oxen are cattle trained as draft animals. Oxen can pull heavier loads and for a longer period of time than horses.[110] Oxen are used worldwide, especially in developing countries. There are some 11 million draft oxen in sub-Saharan Africa,[111] while in 1998 India had over 65 million oxen.[112] At the start of the 21st century, about half the world's crop production depended on land preparation by draft animals.[113]

Hides

[edit]Cattle are not often kept solely for hides, and they are usually a by-product of beef production. Hides are used mainly for leather products such as shoes. In 2012, India was the world's largest producer of cattle hides.[114] Cattle hides account for around 65% of the world's leather production.[115][116]

Health

[edit]Pests and diseases

[edit]Cattle are subject to pests including arthropod parasites such as ticks (which can in turn transmit diseases caused by bacteria and protozoa),[117] and diseases caused by pathogens including bacteria and viruses. Some viral diseases are spread by insects—i.e. bluetongue disease is spread by midges. Psoroptic mange is a disabling skin condition caused by mites. Bovine tuberculosis is caused by a bacterium; it causes disease in humans and in wild animals such as deer and badgers.[118] Foot-and-mouth disease is caused by a virus, affects a range of hoofed livestock and is highly contagious.[119] Bovine spongiform encephalopathy is a neurodegenerative disease spread by a prion, a misfolded brain protein, in contaminated meat.[120] Among the intestinal parasites of cattle are Paramphistomum flukes, affecting the rumen, and hookworms in the small intestine.[121]

Role of climate change

[edit]

Climate change is expected to exacerbate heat stress in cattle, and for longer periods.[123] Heat-stressed cattle may experience accelerated breakdown of adipose tissue by the liver, causing lipidosis.[124] Cattle eat less when heat stressed, resulting in ruminal acidosis, which can lead to laminitis. Cattle can attempt to deal with higher temperatures by panting more often; this rapidly decreases carbon dioxide concentrations at the price of increasing pH, respiratory alkalosis. To deal with this, cattle are forced to shed bicarbonate through urination, at the expense of rumen buffering. These two pathologies can both cause lameness.[124] Another specific risk is mastitis.[124] This worsens as Calliphora blowflies increase in number with continued warming, spreading mastitis-causing bacteria.[125] Ticks too are likely to increase in temperate zones as the climate warms, increasing the risk of tick-borne diseases.[126] Both beef and milk production are likely to experience declines due to climate change.[122][127]

Impact of cattle husbandry

[edit]On public health

[edit]Cattle health is at once a veterinary issue (for animal welfare and productivity), a public health issue (to limit the spread of disease), and a food safety issue (to ensure meat and dairy products are safe to eat). These concerns are reflected in farming regulations.[128] These rules can become political matters, as when it was proposed in the UK in 2011 that milk from tuberculosis-infected cattle should be allowed to enter the food chain.[129] Cattle disease attracted attention in the 1980s and 1990s when bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease) broke out in the United Kingdom. BSE can cross into humans as the deadly variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease; 178 people in the UK had died from it by 2010.[130]

On the environment

[edit]

The gut flora of cattle produce methane, a powerful[131] greenhouse gas, as a byproduct of enteric fermentation, with each cow belching out 100kg a year.[132] Additional methane is produced by anaerobic fermentation of stored manure.[133] The FAO estimates that in 2015 around 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions were due to cattle, but this is uncertain.[134] Reducing methane emissions quickly helps limit climate change.[134]

Concentrated animal feeding operations in particular produce substantial amounts of wastewater and manure,[135][136] which can cause environmental harms such as soil erosion, human and animal exposure to toxic chemicals, development of antibiotic resistant bacteria and an increase in E. coli contamination.[137][138]

In many world regions, overgrazing by cattle has reduced biodiversity of the grazed plants and of animals at different trophic levels in the ecosystem.[139] A well documented consequence of overgrazing is woody plant encroachment in rangelands, which significantly reduces the carrying capacity of the land over time.[140]

On animal welfare

[edit]

Cattle husbandry practices including branding,[141] castration,[142] dehorning,[143] ear tagging,[144] nose ringing,[145] restraint,[146] tail docking,[147] the use of veal crates,[148] and cattle prods[149] have raised welfare concerns.[150]

Stocking density is the number of animals within a specified area. High stocking density can affect cattle health, welfare, productivity,[151] and feeding behaviour.[152] Densely-stocked cattle feed more rapidly and lie down sooner, increasing the risk of teat infection, mastitis, and embryo loss.[153][154] The stress and negative health impacts induced by high stocking density such as in concentrated animal feeding operations or feedlots, auctions, and transport may be detrimental to cattle welfare.[155]

To produce milk, most calves are separated from their mothers soon after birth and fed milk replacement to retain the cows' milk for human consumption.[156]Dairy cattle are frequently artificially inseminated.[157] Animal welfare advocates are critical of this practice, stating that this breaks the natural bond between the mother and her calf.[156] The welfare of veal calves is also a concern.[158]

Two sports involving cattle are thought to be cruel by animal welfare groups: rodeos and bullfighting. Such groups oppose rodeo activities including bull riding, calf roping and steer roping, stating that rodeos are unnecessary and cause stress, injury, and death to the animals.[159] In Spain, the Running of the bulls faces opposition due to the stress and injuries incurred by the bulls during the event.[160]

In culture

[edit]From early in civilisation, cattle have been used in barter.[161][162] Cattle play a part in several religions. Veneration of the cow is a symbol of Hindu community identity.[163] Slaughter of cows is forbidden by law in several states of the Indian Union.[164]

The ox is one of the 12-year cycle of animals which appear in the Chinese zodiac. The astrological sign Taurus is represented as a bull in the Western zodiac.[165]

- Cattle in culture

-

St Luke the evangelist depicted with a bull in the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle

-

A legend claims that monks carrying the body of Saint Cuthbert were led by a milk maid who had lost her dun cow. They built Durham Cathedral where it was found.[166]

-

Dutch Golden Age painting: Young Herdsman with Cows by Aelbert Cuyp, 1655–60

-

An Evening at the Hut of the Cow-Herdesses, Knud Bergslien, before 1858

-

Bull in the coat of arms of Turin, Italy

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "kine". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ a b c "cattle, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. 13 October 2024. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "chattel". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ "cow, n.1.". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. 13 October 2024. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ "Antelopes, Gazelles, Cattle, Goats, Sheep, and Relatives: Introduction" (PDF). Princeton University Press. pp. 1–23. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 January 2024. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ Rolf, Megan (February 2017). "Color Patterns in Crossbred Beef Cattle". University of Oklahoma Extension. p. AFS-3173. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "Hereford cattle weight". Archived from the original on 24 January 2015.

- ^ Gallman, Robert E.; Wallis, John Joseph (2007). American Economic Growth and Standards of Living before the Civil War. University of Chicago Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-2812-2349-4.

- ^ McMurry, Bryan (1 February 2009). "Cattle increasing in size". Beef Magazine. Archived from the original on 3 May 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- ^ "Chianina". The Cattle Site. 29 September 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

- ^ "Cattle factsheet". RSPCA. Retrieved 13 February 2024.

- ^ a b c Kibegwa, Felix M.; Bett, Rawlynce C.; Gachuiri, Charles K.; Machuka, Eunice; Stomeo, Francesca; Mujibi, Fidalis D. (13 January 2023). "Diversity and functional analysis of rumen and fecal microbial communities associated with dietary changes in crossbreed dairy cattle". PLOS ONE. 18 (1) e0274371. Bibcode:2023PLoSO..1874371K. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0274371. PMC 9838872. PMID 36638091.

- ^ Hua, Dengke; Hendriks, Wouter H.; Xiong, Benhai; Pellikaan, Wilbert F. (3 November 2022). "Starch and Cellulose Degradation in the Rumen and Applications of Metagenomics on Ruminal Microorganisms". Animals. 12 (21): 3020. doi:10.3390/ani12213020. PMC 9653558. PMID 36359144.

- ^ a b Orr, Adam I. (28 June 2023). "How Cows Eat Grass: Exploring Cow Digestion". Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 13 February 2024.[dead link]

- ^ Roche, J.R.; Lee, J.M.; Berry, D.P. (2006). "Pre-Conception Energy Balance and Secondary Sex Ratio—Partial Support for the Trivers-Willard Hypothesis in Dairy Cows". Journal of Dairy Science. 89 (6). American Dairy Science Association: 2119–2125. doi:10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(06)72282-2. PMID 16702278.

- ^ Frandson, Rowen D.; Wilke, W. Lee; Fails, Anna Dee (2013). Anatomy and Physiology of Farm Animals. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 449–451. ISBN 978-1-118-68601-0.

- ^ Hopper, Richard M. (2014). "32. Artificial Insemination; 33. Pharmacological Intervention of Estrous Cycles". Bovine Reproduction. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-47085-5.

- ^ Youngquist, Robert S.; Threlfall, Walter R. (10 October 2006). Current Therapy in Large Animal Theriogenology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 940. ISBN 978-1-4377-1340-4.

- ^ Edwards, S.A.; Broom, D.M. (1982). "Behavioural interactions of dairy cows with their newborn calves and the effects of parity". Animal Behaviour. 30 (2): 525–535. doi:10.1016/s0003-3472(82)80065-1. S2CID 53145854.

- ^ a b c d Reinhardt, C.; Reinhardt, A.; Reinhardt, V. (1986). "Social behaviour and reproductive performance in semi-wild Scottish Highland cattle". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 15 (2): 125–136. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(86)90058-4.

- ^ Odde, K. G.; Kiracofe, G.H.; Schalles, R.R. (1985). "Suckling behavior in range beef calves". Journal of Animal Science. 61 (2): 307–309. doi:10.2527/jas1985.612307x. PMID 4044428.

- ^ Johnsen, J.F.; Ellingsen, K.; Grøndahl, A.M.; Bøe, K.E.; Lidfors, L.; Mejdell, C.M. (2015). "The effect of physical contact between dairy cows and calves during separation on their post-separation behavioural". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 166: 11–19. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2015.03.002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 July 2017.

- ^ a b Lecorps, Benjamin; Weary, Daniel M.; von Keyserlingk, Marina A. G. (23 January 2018). "Pessimism and fearfulness in dairy calves". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 1421. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.1421L. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-17214-3. PMC 5780456. PMID 29362460.

- ^ Bailey, D.W.; Rittenhouse, L.R.; Hart, R.H.; Richards, R.W (1989). "Characteristics of spatial memory in cattle". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 23 (4): 331–340. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(89)90101-9.

- ^ Ksiksi, T.; Laca, E.A. (2002). "Cattle do remember locations of preferred food over extended periods". Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 15 (6): 900–904. doi:10.5713/ajas.2002.900.

- ^ Kovalčik, K.; Kovalčik, M. (1986). "Learning ability and memory testing in cattle of different ages". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 15 (1): 27–29. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(86)90019-5.

- ^ Schaeffer, R.G.; Sikes, J.D. (1971). "Discrimination learning in dairy calves". Journal of Dairy Science. 54 (6): 893–896. doi:10.3168/jds.s0022-0302(71)85937-4. PMID 5141440.

- ^ a b c d Coulon, M.; Baudoin, C.; Heyman, Y.; Deputte, B.L. (2011). "Cattle discriminate between familiar and unfamiliar conspecifics by using only head visual cues". Animal Cognition. 14 (2): 279–290. doi:10.1007/s10071-010-0361-6. PMID 21132446. S2CID 39755371.

- ^ de Passille, A.M.; Rushen, J.; Ladewig, J.; Petherick, C. (1996). "Dairy calves' discrimination of people based on previous handling". Journal of Animal Science. 74 (5): 969–974. doi:10.2527/1996.745969x. PMID 8726728.

- ^ Barfield, C.H.; Tang-Martinez, Z.; Trainer, J.M. (1994). "Domestic calves (Bos taurus) recognize their own mothers by auditory cues". Ethology. 97 (4): 257–264. Bibcode:1994Ethol..97..257B. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.1994.tb01045.x.

- ^ Watts, J.M.; Stookey, J.M. (2000). "Vocal behaviour in cattle: the animal's commentary on its biological processes and welfare". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 67 (1): 15–33. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00108-2. PMID 10719186.

- ^ Coulon, M.; Baudoin, C.; Abdi, H.; Heyman, Y.; Deputte, B.L. (2010). "Social behavior and kin discrimination in a mixed group of cloned and non cloned heifers (Bos taurus)". Theriogenology. 74 (9): 1596–1603. doi:10.1016/j.theriogenology.2010.06.031. PMID 20708240.

- ^ Phillips, C.J.C.; Oevermans, H.; Syrett, K.L.; Jespersen, A.Y.; Pearce, G.P. (2015). "Lateralization of behavior in dairy cows in response to conspecifics and novel persons". Journal of Dairy Science. 98 (4): 2389–2400. doi:10.3168/jds.2014-8648. PMID 25648820.

- ^ Robins, A.; Phillips, C. (2010). "Lateralised visual processing in domestic cattle herds responding to novel and familiar stimuli". Laterality. 15 (5): 514–534. doi:10.1080/13576500903049324. PMID 19629847. S2CID 13283847.

- ^ a b c Adamczyk, K.; Górecka-Bruzda, A.; Nowicki, J.; Gumułka, M.; Molik, E.; Schwarz, T.; Klocek, C. (2015). "Perception of environment in farm animals – A review". Annals of Animal Science. 15 (3): 565–589. doi:10.1515/aoas-2015-0031.

- ^ Jacobs, G.H.; Deegan, J.F.; Neitz, J. (March 1998). "Photopigment basis for dichromatic color vision in cows, goats and sheep". Visual Neuroscience. 15 (3): 581–584. doi:10.1017/s0952523898153154. PMID 9685209. S2CID 3719972.

- ^ Bell, F.R.; Sly, J. (1983). "The olfactory detection of sodium and lithium salts by sodium deficient cattle". Physiology & Behavior. 31 (3): 307–312. doi:10.1016/0031-9384(83)90193-2. PMID 6634998. S2CID 34619742.

- ^ Heffner, R.S.; Heffner, H.E. (1983). "Hearing in large mammals: Horses (Equus caballus) and cattle (Bos taurus)". Behavioral Neuroscience. 97 (2): 299–309. doi:10.1037/0735-7044.97.2.299.

- ^ Heffner, R.S.; Heffner, H.E. (1992). "Hearing in large mammals: sound-localization acuity in cattle (Bos taurus) and goats (Capra hircus)". Journal of Comparative Psychology. 106 (2): 107–113. doi:10.1037/0735-7036.106.2.107. PMID 1600717.

- ^ Lange, Annika; Bauer, Lisa; Futschik, Andreas; Waiblinger, Susanne; Lürzel, Stephanie (15 October 2020). "Talking to Cows: Reactions to Different Auditory Stimuli During Gentle Human-Animal Interactions". Frontiers in Psychology. 11 579346. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.579346. PMC 7593841. PMID 33178082.

- ^ a b Bouissou, M.F.; Boissy, A.; Le Niendre, P.; Vessier, I. (2001). "The Social Behaviour of Cattle 5.". In Keeling, L.; Gonyou, H. (eds.). Social Behavior in Farm Animals. CABI Publishing. pp. 113–133.

- ^ a b Boissy, A.; Terlouw, C.; Le Neindre, P. (1998). "Presence of cues from stressed conspecifics increases reactivity to aversive events in cattle: evidence for the existence of alarm substances in urine". Physiology and Behavior. 63 (4): 489–495. doi:10.1016/s0031-9384(97)00466-6. PMID 9523888. S2CID 36904002.

- ^ "Signs of Heat (Heat Detection and Timing of Insemination for Cattle)". Heat Detection and Timing of Insemination for Cattle (Penn State Extension). Archived from the original on 5 November 2016.

- ^ Knierim, U.; Irrgang, N.; Roth, B.A. (2015). "To be or not to be horned–consequences in cattle". Livestock Science. 179: 29–37. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2015.05.014.

- ^ Kondo, S.; Sekine, J.; Okubo, M.; Asahida, Y. (1989). "The effect of group size and space allowance on the agonistic and spacing behavior of cattle". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 24 (2): 127–135. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(89)90040-3.

- ^ Rutter, S.M. (2006). "Diet preference for grass and legumes in free-ranging domestic sheep and cattle: current theory and future application". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 97 (1): 17–35. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2005.11.016.

- ^ Laca, E.A.; Ungar, E.D.; Seligman, N.; Demment, M.W. (1992). "Effects of sward height and bulk density on bite dimensions of cattle grazing homogeneous swards". Grass and Forage Science. 47 (1): 91–102. Bibcode:1992GForS..47...91L. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2494.1992.tb02251.x.

- ^ Bailey, D.W.; Gross, J.E.; Laca, E.A.; Rittenhouse, L.R.; Coughenour, M.B.; Swift, D.M.; Sims, P.L. (1996). "Mechanisms that result in large herbivore grazing distribution patterns". Journal of Range Management. 49 (5): 386–400. doi:10.2307/4002919. hdl:10150/644282. JSTOR 4002919.

- ^ Forbes, T.D.A.; Hodgson, J. (1985). "The reaction of grazing sheep and cattle to the presence of dung from the same or the other species". Grass and Forage Science. 40 (2): 177–182. Bibcode:1985GForS..40..177F. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2494.1985.tb01735.x.

- ^ Daniels, M.J.; Ball, N.; Hutchings, M.R.; Greig, A. (2001). "The grazing response of cattle to pasture contaminated with rabbit faeces and the implications for the transmission of paratuberculosis". The Veterinary Journal. 161 (3): 306–313. doi:10.1053/tvjl.2000.0550. PMID 11352488.

- ^ Proctor, Helen S.; Carder, Gemma (9 October 2014). "Can ear postures reliably measure the positive emotional state of cows?". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 161: 20–27. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2014.09.015. Archived from the original on 3 October 2020. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- ^ Brand, B.; Hadlich, F.; Brandt, B.; Schauer, N.; Graunke, K.L.; Langbein, J.; Schwerin, M. (2015). "Temperament type specific metabolite profiles of the prefrontal cortex and serum in cattle". PLOS One. 10 (4) e0125044. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1025044B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125044. PMC 4416037. PMID 25927228.

- ^ Réale, D.; Reader, S.M.; Sol, D.; McDougall, P.T.; Dingemanse, N.J. (2007). "Integrating animal temperament within ecology and evolution". Biological Reviews. 82 (2): 291–318. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185x.2007.00010.x. hdl:1874/25732. PMID 17437562. S2CID 44753594.

- ^ Hagen, K.; Broom, D. (2004). "Emotional reactions to learning in cattle". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 85 (3–4): 203–213. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2003.11.007.

- ^ Daros, R.R.; Costa, J.H.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.; Hötzel, M.J.; Weary, D.M. (2014). "Separation from the dam causes negative judgement bias in dairy calves". PLOS One. 9 (5) e98429. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...998429D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0098429. PMC 4029834. PMID 24848635.

- ^ Neave, H.W.; Daros, R.R.; Costa, J.H.C.; von Keyserlingk, M.A.G.; Weary, D.M. (2013). "Pain and pessimism: Dairy calves exhibit negative judgement bias following hot-iron disbudding". PLOS One. 8 (12) e80556. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...880556N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080556. PMC 3851165. PMID 24324609.

- ^ Boissy, A.; Le Neindre, P. (1997). "Behavioral, cardiac and cortisol responses to brief peer separation and reunion in cattle". Physiology & Behavior. 61 (5): 693–699. doi:10.1016/s0031-9384(96)00521-5. PMID 9145939. S2CID 8507049.

- ^ Piller, Carol A.K.; Stookey, Joseph M; Watts, Jon M. (1999). "Effects of mirror-image exposure on heart rate and movement of isolated heifers". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 63 (2): 93–102. doi:10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00010-6.

- ^ "40 Winks?" Jennifer S. Holland, National Geographic Vol. 220, No. 1. July 2011.

- ^ Asprea, Lori; Sturtz, Robin (2012). Anatomy and physiology for veterinary technicians and nurses a clinical approach. Chichester: Iowa State University Pre. p. 109. ISBN 978-1-118-40584-0.

- ^ "Animal MythBusters". www.mvma.ca. Manitoba Veterinary Medical Association. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016.

- ^ Collins, Nick (6 September 2013). "Cow tipping myth dispelled". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ a b Talenti, A.; Powell, J.; Hemmink, J. D.; Cook, E. A. J.; Wragg, D.; Jayaraman, S.; et al. (17 February 2022). "A cattle graph genome incorporating global breed diversity". Nature Communications. 13 (1): 910. Bibcode:2022NatCo..13..910T. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28605-0. PMC 8854726. PMID 35177600.

- ^ Brown, David (23 April 2009). "Scientists Unravel Genome of the Cow". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2009.

- ^ Gill, Victoria (23 April 2009). "BBC: Cow genome 'to transform farming'". BBC News. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ Canario, L.; Mignon-Grasteau, S.; Dupont-Nivet, M.; Phocas, F. (2013). "Genetics of behavioural adaptation of livestock to farming conditions" (PDF). Animal. 7 (3): 357–377. Bibcode:2013Anim....7..357C. doi:10.1017/S1751731112001978. PMID 23127553.

- ^ Schmutz, S. M.; Stookey, J. M.; Winkelman-Sim, D. C.; Waltz, C. S.; Plante, Y.; Buchanan, F. C. (2001). "A QTL study of cattle behavioral traits in embryo transfer families". Journal of Heredity. 92 (3): 290–292. doi:10.1093/jhered/92.3.290. PMID 11447250.

- ^ Canario, L.; Mignon-Grasteau, S.; Dupont-Nivet, M.; Phocas, F. (2013). "Genetics of behavioural adaptation of livestock to farming conditions" (PDF). Animal. 7 (3): 357–377. Bibcode:2013Anim....7..357C. doi:10.1017/S1751731112001978. PMID 23127553.

- ^ Friedrich, J.; Brand, B.; Schwerin, M. (2015). "Genetics of cattle temperament and its impact on livestock production and breeding – a review". Archives Animal Breeding. 58: 13–21. doi:10.5194/aab-58-13-2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ a b c McTavish, E.J.; Decker, J.E.; Schnabel, R.D.; Taylor, J.F.; Hillis, D.M. (2013). "New World cattle show ancestry from multiple independent domestication events". PNAS. 110 (15): E1398–1406. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110E1398M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1303367110. PMC 3625352. PMID 23530234.

- ^ Bollongino, R.; Burger, J.; Powell, A.; Mashkour, M.; Vigne, J.-D.; Thomas, M. G. (2012). "Modern taurine cattle descended from small number of Near-Eastern founders". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (9): 2101–2104. doi:10.1093/molbev/mss092. PMID 22422765. Op. cit. in Wilkins, Alasdair (28 March 2012). "DNA reveals that cows were almost impossible to domesticate". io9. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012. Retrieved 2 April 2012.

- ^ Decker, J.E.; McKay, S.D.; Rolf, M.M.; Kim, J.; Molina Alcalá, A.; Sonstegard, T.S.; et al. (2014). "Worldwide patterns of ancestry, divergence, and admixture in domesticated cattle". PLOS Genet. 10 (3) e1004254. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004254. PMC 3967955. PMID 24675901.

- ^ a b Pitt, Daniel; Sevane, Natalia; Nicolazzi, Ezequiel L.; MacHugh, David E.; Park, Stephen D. E.; Colli, Licia; Martinez, Rodrigo; Bruford, Michael W.; Orozco-terWengel, Pablo (2019). "Domestication of cattle: Two or three events?". Evolutionary Applications. 12 (1): 123–136. Bibcode:2019EvApp..12..123P. doi:10.1111/eva.12674. PMC 6304694. PMID 30622640.

- ^ Ajmone-Marsan, Paolo; Garcia, J.F.; Lenstra, Johannes (January 2010). "On the origin of cattle: How aurochs became domestic and colonized the world". Evolutionary Anthropology. 19: 148–157. doi:10.1002/evan.20267. S2CID 86035650. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ a b Grubb, P. (2005). "Bos taurus". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 637–722. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ "Explore the Database". www.mammaldiversity.org. Retrieved 21 August 2021.

- ^ Gentry, Anthea; Clutton-Brock, Juliet; Groves, Colin P. (1 May 2004). "The naming of wild animal species and their domestic derivatives". Journal of Archaeological Science. 31 (5): 645–651. Bibcode:2004JArSc..31..645G. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2003.10.006.

- ^ Mummolo, Jonathan (11 August 2007). "Yattle What?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 1 July 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2023.

- ^ Groves, C. P. (1981). "Systematic relationships in the Bovini (Artiodactyla, Bovidae)". Zeitschrift für Zoologische Systematik und Evolutionsforschung. 4: 264–278., quoted in Grubb, P. (2005). "Genus Bison". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 637–722. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Takeda, Kumiko; et al. (April 2004). "Mitochondrial DNA analysis of Nepalese domestic dwarf cattle Lulu". Animal Science Journal. 75 (2): 103–110. doi:10.1111/j.1740-0929.2004.00163.x.

- ^ Van Vuure, C.T. 2003. De Oeros – Het spoor terug (in Dutch), Cis van Vuure, Wageningen University and Research Centrum: quoted by The Extinction Website: Bos primigenius primigenius. Archived 20 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Heck, H. (1951). "The Breeding-Back of the Aurochs". Oryx. 1 (3): 117–122. doi:10.1017/S0030605300035286.

- ^ Pitt, Daniel; Sevane, Natalia; Nicolazzi, Ezequiel L.; MacHugh, David E.; Park, Stephen D. E.; Colli, Licia; Martinez, Rodrigo; Bruford, Michael W.; Orozco-terWengel, Pablo (January 2019). "Domestication of cattle: Two or three events?". Evolutionary Applications. 12 (1): 123–136. Bibcode:2019EvApp..12..123P. doi:10.1111/eva.12674. PMC 6304694. PMID 30622640.

- ^ Strydom, P.E.; Naude, R.T.; Smith, M.F.; Kotze, A.; Scholtz, M.M.; Van Wyk, J.B. (1 March 2001). "Relationships between production and product traits in subpopulations of Bonsmara and Nguni cattle". South African Journal of Animal Science. 31 (3): 181–194. doi:10.4314/sajas.v31i3.3801.

- ^ Meghen, C.; MacHugh, D.E.; Bradley, D.G. "Genetic characterization and West African cattle". fao.org. Archived from the original on 26 February 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2021.

- ^ "Definition of Feral cattle". Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Sahagun, Louis (2 March 2018). "Feral cattle terrorize hikers and devour native plants in a California national monument". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "NGRC Bos taurus". www.nodai-genome.org. Archived from the original on 23 February 2016.

- ^ "口之島牛(Bos Taurus)の成長曲線の作成とその特徴" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ^ "Science – Chillingham Wild Cattle". chillinghamwildcattle.com. 16 June 2015. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016.

- ^ "Alaska Isle a Corral For Feral Cattle Herd; U.S. Wants to Trade Cows for Birds". The Washington Post. 23 October 2005. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- ^ a b "2. AFOs and CAFOs". NPDES Permit Writers' Manual for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: United States Environmental Protection Agency. February 2012. EPA 833-F-12-001.

- ^ Lott, Dale F.; Hart, Benjamin L. (October 1979). "Applied ethology in a nomadic cattle culture". Applied Animal Ethology. 5 (4): 309–319. doi:10.1016/0304-3762(79)90102-0.

- ^ Krebs, J.R.; Anderson, T.; Clutton-Brock, W.T.; et al. (1997). Bovine tuberculosis in cattle and badgers: an independent scientific review (PDF) (Report). Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2004. Retrieved 4 September 2006.

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. USA: University of Chicago Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ Bar-On, Yinon M.; Phillips, Rob; Milo, Ron (21 May 2018). "The biomass distribution on Earth". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (25): 6506–6511. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.6506B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1711842115. PMC 6016768. PMID 29784790.

- ^ Cook, Rob (9 January 2024). "Ranking Of Countries With The Most Cattle". National Beef Wire. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ "Cattle". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ "FAOSTAT". www.fao.org. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ "AskUSDA: What is the most consumed meat in the world?". U.S. Department of Agriculture. 17 July 2019. Retrieved 5 December 2022.

- ^ "Mapped: Global Livestock Distribution and Density". Visual Capitalist. 23 July 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ a b "UK Dairy Cows". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ a b c "Compassion in World Farming: Dairy Cattle". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ Pearson, R.E.; Fulton, L.A.; Thompson, P.D.; Smith, J.W. (1979). "Milking 3 Times per day". Journal of Dairy Science. 62 (12): 1941–1950. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(79)83526-2. PMID 541464.

- ^ Larry Smith, K.; Schanbacher, F. L. (1 June 1973). "Hormone Induced Lactation in the Bovine. I. Lactational Performance Following Injections of 17β-Estradiol and Progesterone1". Journal of Dairy Science. 56 (6): 738–743. doi:10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(73)85243-9. PMID 4708130.

- ^ "About calves reared for veal". Compassion in World Farming. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ^ "Major producers of cow milk worldwide in 2023, by country". Statista. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ "Buffalo Milk". Tridge. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

FAO Code: 0951 - Raw milk of buffalo

- ^ "India Largest Producer of Milk in the World". Press Information Bureau, Government of India. 1 June 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Taylor, Tess (3 May 2011). "On Small Farms, Hoof Power Return s". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2011.

- ^ Muruvimi, F.; Ellis-Jones, J. (1999). "A farming systems approach to improving draft animal power in Sub-Saharan Africa". In Starkey, P.; Kaumbutho, P. (eds.). Meeting the challenges of animal traction. London: Intermediate Technology Publications. pp. 10–19.

- ^ Phaniraja, K. L.; Panchasara, H. H. (2009). "Indian draught animals power". Veterinary World (2): 404–407.

- ^ Nicholson, Charles F.; Blake, Robert W.; Reid, Robin S.; Schelhas, John (2001). "Environmental Impacts of Livestock in the Developing World". Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development. 43 (2): 7–17. Bibcode:2001ESPSD..43b...7N. doi:10.1080/00139150109605120. hdl:10568/32888. S2CID 133316829.

- ^ "World Statistical Compendium for raw hides and skins, leather and leather footwear 1993-2012" (PDF). FAO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 January 2015. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "EST: Hides & Skins". Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- ^ "Introduction to Leather". International Council of Tanners. Archived from the original on 4 August 2018. Retrieved 8 August 2018.

- ^ "Ectoparasites of Cattle". NADIS Animal Health Skills. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ "Diseases that affect cattle". Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs. 26 April 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Donaldson, A. I.; Alexandersen, S.; Sorensen, J. H.; Mikkelsen, T. (May 2001). "Relative risks of the uncontrollable (airborne) spread of FMD by different species". Veterinary Record. 148 (19): 602–604. doi:10.1136/vr.148.19.602. PMID 11386448. S2CID 12025498.

- ^ "Bovine Spongiform Encephalopaphy: An Overview" (PDF). Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, United States Department of Agriculture. December 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 March 2008. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ^ VanHoy, Grace (June 2023). "Common Gastrointestinal Parasites of Cattle". MSD Veterinary Manual. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ a b Liu, Weihang; Zhou, Junxiong; Ma, Yuchi; Chen, Shuo; Luo, Yuchuan (3 February 2024). "Unequal impact of climate warming on meat yields of global cattle farming". Communications Earth and Environment. 5 (1): 65. Bibcode:2024ComEE...5...65L. doi:10.1038/s43247-024-01232-x.

- ^ Çaylı, Ali M.; Arslan, Bilge (7 February 2022). "Analysis of the Thermal Environment and Determination of Heat Stress Periods for Dairy Cattle Under Eastern Mediterranean Climate Conditions". Journal of Biosystems Engineering. 47: 39–47. doi:10.1007/s42853-021-00126-6. S2CID 246655199.

- ^ a b c Lacetera, Nicola (3 January 2019). "Impact of climate change on animal health and welfare". Animal Frontiers. 9 (1): 26–31. doi:10.1093/af/vfy030. PMC 6951873. PMID 32002236.

- ^ Goulson, Dave; Derwent, Lara C.; Hanley, Michael E.; Dunn, Derek W.; Abolins, Steven R. (5 September 2005). "Predicting calyptrate fly populations from the weather, and probable consequences of climate change". Journal of Applied Ecology. 42 (5): 795–804. Bibcode:2005JApEc..42..795G. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2005.01078.x. S2CID 3892520.

- ^ Nava, Santiago; Gamietea, Ignacio J.; Morel, Nicolas; Guglielmone, Alberto A.; Estrada-Pena, Agustin (6 July 2022). "Assessment of habitat suitability for the cattle tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus in temperate areas". Research in Veterinary Science. 150: 10–21. doi:10.1016/j.rvsc.2022.04.020. PMID 35803002. S2CID 250252036.

- ^ Ranjitkar, Sailesh; Bu, Dengpan; Van Wijk, Mark; Ma, Ying; Ma, Lu; Zhao, Lianshen; Shi, Jianmin; Liu, Chousheng; Xu, Jianchu (2 April 2020). "Will heat stress take its toll on milk production in China?". Climatic Change. 161 (4): 637–652. Bibcode:2020ClCh..161..637R. doi:10.1007/s10584-020-02688-4. S2CID 214783104.

- ^ "Cattle Disease Guide". Archived from the original on 28 November 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (17 May 2011). "Easing of farming regulations could allow milk from TB-infected cattle into food chain". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ^ Garske, Tini; Ghani, Azra C. (23 December 2010). "Uncertainty in the Tail of the Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Epidemic in the UK". PLOS ONE. 5 (12) e15626. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515626G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015626. PMC 3009744. PMID 21203419.

- ^ "Methane vs Carbon Dioxide: A Greenhouse Gas Showdown". One Green Planet. 2015. Retrieved 29 January 2022.

- ^ tdus (27 June 2019). "Cows and Climate Change". UC Davis. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ US EPA. 2012. Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gases emissions and sinks: 1990–2010. US Environmental Protection Agency. EPA 430-R-12-001. Section 6.2.

- ^ a b "Livestock Don't Contribute 14.5% of Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions". The Breakthrough Institute. Retrieved 25 March 2024.

- ^ Bradford, Scott A.; Segal, Eran; Zheng, Wei; Wang, Qiquan; Hutchins, Stephen R. (2008). "Reuse of Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation Wastewater on Agricultural Lands". Journal of Environmental Quality. 37 (S5): S97 – S115. Bibcode:2008JEnvQ..37..-97B. doi:10.2134/jeq2007.0393. PMID 18765783.

- ^ Koelsch, Richard; Balvanz, Carol; George, John; Meyer, Dan; Nienaber, John; Tinker, Gene. "Applying Alternative Technologies to CAFOs: A Case Study" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ^ Ikerd, John. "The Economics of CAFOs & Sustainable Alternatives". Web.missouri.edu. Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ Gurian-Sherman, Doug. "CAFOs Uncovered: The Untold Costs of Confined Animal Feeding Operations" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- ^ Filazzola, Alessandro; et al. (2020). "The effects of livestock grazing on biodiversity are multi-trophic: a meta-analysis". Ecology Letters. 23 (8): 1298–1309. Bibcode:2020EcolL..23.1298F. doi:10.1111/ele.13527. PMID 32369874.

- ^ Archer, Steven R.; Andersen, Erik M.; Predick, Katharine I.; Schwinning, Susanne; Steidl, Robert J.; Woods, Steven R. (2017). "Woody Plant Encroachment: Causes and Consequences". In Briske, David D. (ed.). Rangeland Systems. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 25–84. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46709-2_2. ISBN 978-3-319-46707-8.

- ^ Schwartzkopf-Genswein, K. S.; Stookey, J. M.; Welford, R. (1 August 1997). "Behavior of cattle during hot-iron and freeze branding and the effects on subsequent handling ease". Journal of Animal Science. 75 (8): 2064–2072. doi:10.2527/1997.7582064x. PMID 9263052.

- ^ Coetzee, Hans (19 May 2013). Pain Management, An Issue of Veterinary Clinics: Food Animal Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. PT70. ISBN 978-1-4557-7376-3.

- ^ "Welfare Implications of Dehorning and Disbudding Cattle". www.avma.org. Archived from the original on 5 September 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Goode, Erica (25 January 2012). "Ear-Tagging Proposal May Mean Fewer Branded Cattle". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Grandin, Temple (21 July 2015). Improving Animal Welfare, 2 Edition: A Practical Approach. CABI. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-78064-467-7.

- ^ "Restraint of Livestock". www.grandin.com. Archived from the original on 13 December 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- ^ Doyle, Rebecca; Moran, John (3 February 2015). Cow Talk: Understanding Dairy Cow Behaviour to Improve Their Welfare on Asian Farms. Csiro Publishing. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1-4863-0162-1.

- ^ McKenna, C. (2001). "The case against the veal crate: An examination of the scientific evidence that led to the banning of the veal crate system in the EU and of the alternative group housed systems that are better for calves, farmers and consumers" (PDF). Compassion in World Farming. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Using Prods and Persuaders Properly to Handle Cattle, Pigs, and Sheep". grandin.com. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ "Cattle". awionline.org. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Grant, R. (2011). "Taking advantage of natural behavior improves dairy cow performance". Archived from the original on 2 December 2016.

- ^ Huzzey, J.; Keyserlingk, M.; Overton, T. (2012). "The behaviour and physiological consequences of overstocking dairy cattle". American Association of Bovine Practitioners: 92–97. doi:10.21423/aabppro20123879. S2CID 203405605.

- ^ Tyler, J.W; Fox, L.K.; Parish, S.M.; Swain, J.; Johnson, D.J.; Grassechi, H.A. (1997). "Effect of feed availability on post-milking standing time in dairy cows". Journal of Dairy Research. 64 (4): 617–620. doi:10.1017/s0022029997002501. PMID 9403771. S2CID 41754001.

- ^ Schefers, J.M.; Weigel, K.A.; Rawson, C.L.; Zwald, N.R.; Cook, N.B. (2010). "Management practices associated with conception rate and service rate of lactating Holstein cows in large, commercial dairy herds". Journal of Dairy Science. 93 (4): 1459–1467. doi:10.3168/jds.2009-2015. PMID 20338423.

- ^ Grandin, Temple (1 December 2016). "Evaluation of the welfare of cattle housed in outdoor feedlot pens". Veterinary and Animal Science. 1–2: 23–28. doi:10.1016/j.vas.2016.11.001. PMC 7386639. PMID 32734021.

- ^ a b Vegetarian Society. "Cattle". Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Jacobs, Andrew (29 December 2020). "Is Dairy Farming Cruel to Cows?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 8 March 2025.

- ^ "EFSA: house calves in small groups to improve welfare". European Food Safety Authority. 29 March 2023. Retrieved 14 February 2024.

- ^ Smith, Michael (17 July 2008). "Animal rights group targets popular rodeo". msnbc.com. AP. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Antebi, Andres. "Passion for bulls in the street" (in Catalan). Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 23 October 2020.

- ^ Glyn Davies; Julian Hodge Bank (2002). A history of money: from ancient times to the present day. University of Wales Press. pp. 42–44. ISBN 978-0-7083-1717-4.

- ^ Huerta de Soto, Jesús (2006). Money, Bank Credit, and Economic Cycles. Ludwig von Mises Institute. p. 51. ISBN 978-1-61016-388-0.

- ^ Jha, D. N. (2002). The myth of the holy cow. London: Verso. pp. 20, 130. ISBN 978-1-85984-676-6.

- ^ "India Supreme Court suspends cattle slaughter ban". BBC News. 11 July 2017. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2024.

Cows are considered holy by India's majority Hindu population and slaughtering them is already banned in most but not all states,

- ^ "Taurus". The Warburg Institute. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Cuthbert's Move to Durham: Two Stories". Durham Castle and Cathedral. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Cattle Today (2006). Breeds of beef cattle.

- Johns, Catherine (2011). Cattle: History, Myth, Art. London: The British Museum Press. ISBN 978-0-7141-5084-0.

- Oklahoma State University (OSU). 2006. Breeds of Cattle. Retrieved 5 January 2007.

- Purdy, Herman R.; R. John Dawes; Robert Hough (2008). Breeds Of Cattle (2nd ed.). A visual textbook containing History/Origin, Phenotype & Statistics of 45 breeds.

- Rath, S. 1998. The Complete Cow. Stillwater, MN: Voyageur Press. ISBN 0-89658-375-9.

External links

[edit] Data related to Cattle at Wikispecies

Data related to Cattle at Wikispecies Media related to Bos taurus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bos taurus at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Bull (cattle) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Bull (cattle) at Wikimedia Commons

Cattle

View on GrokipediaTaxonomy and Evolution

Etymology and Nomenclature

The word "cattle" entered Middle English as catel or cadel around the mid-13th century, derived from Anglo-Norman catel meaning "personal property" or "chattel," which traces back to Medieval Latin capitale ("property, principal, chief") from Latin capitalis ("of the head").[10] [11] This etymology underscores the historical role of livestock as a primary form of movable wealth in medieval Europe, where cattle represented economic value akin to money or land, rather than denoting the animals exclusively at first.[10] Over time, the term narrowed in English to refer specifically to bovine livestock, replacing older native terms like Old English cū (cow) or oxa (ox), which persist in archaic or dialectal use.[10] "Cattle" functions as a collective plural noun without a singular form in modern English, encompassing both sexes and all ages of domesticated bovines; the term is never used for a single animal.[10] In broader historical contexts, cognates in Romance languages (e.g., French cheptel for livestock holdings) retain the property connotation, while Germanic languages derive bovine terms from Proto-Indo-European roots like gʷṓws (yielding English "cow" via cū and "kine" as an archaic plural).[12] The shift to animal-specific usage in English likely accelerated with Norman influence post-1066, as Anglo-French legal and economic texts emphasized herds as capital assets.[10] Nomenclature for cattle distinguishes primarily by sex, reproductive status, age, and purpose, reflecting practical classifications in agriculture and husbandry.[13] Adult females that have calved at least once are termed "cows"; pre-calving females are "heifers."[14] [15] Intact adult males are "bulls," while castrated males raised for beef are "steers"; an "ox" typically denotes a mature castrated male (often a steer over four years old) trained for draft work like plowing or hauling.[13] [14] Young cattle under one year are "calves," with sex-specific variants like "bull calf" or "heifer calf."[15]| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Cow | Mature female bovine that has produced at least one calf.[14] |

| Heifer | Young female bovine that has not yet calved.[14] |

| Bull | Intact adult male bovine.[14] |

| Steer | Castrated male bovine, typically raised for meat.[13] |

| Ox | Mature castrated male trained for work (often a steer ≥4 years old).[13] |

| Calf | Bovine under one year old, regardless of sex.[15] |

Phylogenetic Origins

Domestic cattle belong to the genus Bos within the subfamily Bovinae of the family Bovidae, which encompasses ruminant artiodactyls including antelopes, buffaloes, and bison. The Bovinae subfamily shares a common ancestor dating to the Middle Miocene, approximately 15.78 million years ago, as inferred from molecular phylogenies based on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA sequences.[18] Within Bovinae, the tribe Bovini includes the genus Bos, which diverged from lineages leading to bison (Bison) and buffaloes (Bubalus) around 5-10 million years ago, supported by analyses of amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers and complete mitochondrial genomes.[19] [20] The direct progenitor of domestic cattle is the extinct aurochs (Bos primigenius), a large wild bovine that inhabited Eurasia, North Africa, and parts of Indian subcontinent from the Pleistocene epoch until its final extinction in 1627 AD in Poland. Phylogenetic reconstructions using ancient DNA from aurochs remains reveal distinct regional populations of B. primigenius, with Eurasian and Near Eastern lineages contributing to taurine cattle (Bos taurus) and Indian subcontinental forms to zebu cattle (Bos indicus).[21] [22] Genetic studies indicate that Bos species, including the aurochs, form a monophyletic clade within Bovini, characterized by adaptations such as horn morphology and body size evident in fossil records from the late Miocene onward.[23] Mitochondrial DNA haplogroup analyses confirm that all modern domestic cattle trace matrilineally to a small founding population of approximately 80 wild female aurochs domesticated independently in the Near East around 10,500 years ago for taurines and later in the Indus Valley of the Indian subcontinent for zebus.[2] [24] This bottleneck is evidenced by low mtDNA diversity in contemporary breeds compared to wild Bovinae relatives, with taurine lineages showing T, P, and Q haplogroups predominant in European and African cattle, respectively.[25] Ancient genomic data further highlight ongoing introgression from wild aurochs into early domestic herds, maintaining traces of ancestral genetic variation until selective breeding reduced it.[26]Domestication Process

Domestic cattle (Bos taurus and Bos indicus) originated from the wild aurochs (Bos primigenius), with domestication occurring independently in two primary events. Taurine cattle (Bos taurus) were domesticated from Eurasian aurochs in the Near East during the Neolithic period, with genetic evidence indicating a founding population as small as 80 individuals approximately 10,500 years ago.[2] Archaeological records from Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites in the Taurus Mountains provide the earliest substantive evidence of cattle management transitioning from hunting to herding, marked by smaller body sizes and altered horn morphologies consistent with selective breeding for manageability.[27] Indicine cattle (Bos indicus), or zebu, underwent separate domestication from Indian aurochs subspecies in the Indus Valley region of the Indian subcontinent around 7,000 to 8,000 years ago, as supported by mitochondrial DNA analyses and archaeological findings of humped cattle remains in early Harappan sites.[28] This process involved initial capture and containment of wild herds, followed by artificial selection favoring traits such as heat tolerance, disease resistance, and draft utility, which differentiated indicine from taurine lineages genetically.[1] Hybridization between taurine and indicine cattle occurred later in the Near East around 4,000 years ago, introducing zebu traits into some African and Asian populations. Genetic studies reveal a domestication bottleneck for taurine cattle, with reduced genetic diversity reflecting intense human-directed breeding pressures that prioritized milk yield, meat production, and docility over wild foraging behaviors.[29] The spread of domesticated cattle followed human migrations, with taurine cattle introduced to Europe by Neolithic farmers around 8,500 years ago, evidenced by ancient DNA from Iranian sites showing continuity with modern European breeds.[30] In Africa, taurine lineages arrived via the Near East, while indicine influences came through later admixtures, underscoring the role of pastoralism in facilitating rapid dispersal and adaptation to diverse environments.[31] These domestication events transformed cattle from large, aggressive wild herbivores into versatile livestock, driven by empirical human needs for reliable protein sources and labor, without reliance on unsubstantiated cultural narratives.[32]Biology and Physiology

Physical Characteristics

![Charolais bull][float-right] Cattle (Bos taurus and Bos indicus) are large, quadrupedal ungulates characterized by cloven hooves and a robust body structure adapted for grazing.[33] Their build features a relatively small head, strong neck, and bulky torso supported by sturdy limbs, with body size varying significantly by breed and sex. Mature females generally weigh 360–1,100 kg and stand 1.2–1.5 m at the shoulder, while males are larger, often reaching 450–1,800 kg and up to 1.8 m in height for breeds like Chianina.[34] [35] Sexual dimorphism is pronounced, with bulls exhibiting thicker necks, broader shoulders, and more muscular frames compared to cows.[4] Horns, when present, emerge from the sides of the head above the ears and curve upward or outward, serving roles in defense and mate selection; however, many modern breeds are polled through selective breeding.[36] [37] Coat color and pattern diversity includes solid black (e.g., Angus), red (e.g., Hereford), or spotted (e.g., Simmental), with short hair covering a thin, pigmented skin that varies in attachment and dewlap development.[38] [36] Breed-specific traits reflect purpose: beef cattle display compact, muscular bodies with even fat distribution for meat yield, averaging 1,000–1,300 pounds in breeds like Angus, whereas dairy cattle are leaner and more angular, prioritizing udder capacity over muscling.[39] [40] The bovine udder consists of four separate quarters, each with a teat, suspended in the inguinal region and highly developed in dairy breeds for milk production.[41] Bos indicus breeds additionally feature dorsal humps, loose skin folds, and longer ears for heat dissipation in tropical climates.[35]Digestive and Metabolic Systems

Cattle feature a ruminant digestive system with a single stomach divided into four compartments: the rumen, reticulum, omasum, and abomasum.[42] The rumen, the largest compartment, can hold approximately 25 gallons of ingesta and serves as the primary site for microbial fermentation of fibrous plant material.[43] Microorganisms in the rumen break down cellulose and other complex carbohydrates into volatile fatty acids (VFAs), primarily acetate, propionate, and butyrate, which provide 70-80% of the animal's energy requirements.[44] The reticulum functions as a sieve, retaining larger feed particles in the rumen while directing smaller ones toward the omasum; it also traps indigestible objects like stones or metal.[45] Attached to the reticulum, the omasum contains numerous leaf-like folds that absorb water, VFAs, and some minerals from the digesta.[46] The abomasum, the "true" stomach, secretes hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes to further break down proteins and partially digested feed, resembling the stomach of non-ruminants.[42] During rumination, cattle regurgitate partially fermented boluses (cud) from the rumen, re-chew them to increase surface area, and reswallow, enhancing microbial breakdown efficiency.[47] VFAs produced in the rumen are absorbed across the rumen wall into the bloodstream, where acetate supports fat synthesis, propionate contributes to gluconeogenesis for glucose production, and butyrate provides energy for rumen epithelial cells.[48] This fermentation-based metabolism enables cattle to derive energy from low-quality forages indigestible to monogastrics, though it results in methane production as a byproduct.[49] In high-producing dairy cattle, metabolic demands elevate VFA needs, influencing feed efficiency and health.[50]Reproduction and Lifecycle

Cattle reach sexual maturity at varying ages depending on breed, nutrition, and sex; heifers typically attain puberty between 11 and 15 months, while bulls do so around 9 to 12 months.[51][52] Females exhibit estrus cycles roughly every 21 days outside pregnancy, facilitating natural mating with bulls. Gestation lasts an average of 283 days, ranging from 279 to 287 days by breed and calf sex, with conception to birth enabling annual calving in fertile cows.[53][54] , expulsion of the calf (typically 30-60 minutes for normal presentation with front feet and nose first), and placental expulsion (3-12 hours post-delivery).[55][56] Newborn calves, usually singletons (twins occur in 1-3% of cases), stand and nurse colostrum within hours to acquire antibodies, with birth weights averaging 30-40 kg for beef breeds.[57] Complications like dystocia arise from fetal malposition or maternal pelvic inadequacy, increasing mortality risks if unassisted.[58] The bovine lifecycle progresses from neonate (0-3 months: nursing and rapid growth), to juvenile (weaning at 6-8 months, somatic development until puberty), adult (reproductive phase with potential for 8-12 calves over 10-15 years), and senescence (declining fertility post-10 years, natural death around 18-22 years absent production culling).[59] Natural longevity reaches 20-30 years in non-commercial settings, limited by factors like dental wear, metabolic decline, and disease susceptibility rather than inherent senescence.[60][61] Males (bulls) exhibit similar timelines but shorter effective reproductive spans due to aggression and management.[62]Sensory and Cognitive Abilities