Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

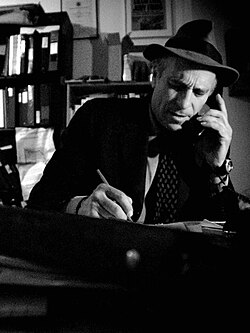

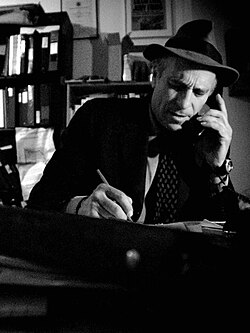

Greg Palast

View on Wikipedia

Gregory Allyn Palast (born June 26, 1952)[1] is an author and a freelance journalist who has often worked for the BBC and The Guardian. His work frequently focuses on corporate malfeasance. He has also worked with labor unions and consumer advocacy groups.

Key Information

Early life, family, and education

[edit]Palast was born in Los Angeles, growing up in the San Fernando Valley community of Sun Valley. Geri Palast is his sister.

Palast said his desire to write about class warfare is rooted in his upbringing in what he describes as the "ass-end of Los Angeles," a neighborhood wedged between a power plant and a dump. He said that kids in that neighborhood had two choices: Vietnam or the auto plant. "We were the losers," he said. He was saved from the war by a favorable draft number. "A lot of people didn't make it out. Because I made it out, and my sister (Geri, a former Clinton administration assistant secretary of labor) made it out, I feel I have this obligation to tell these stories on behalf of all of those people who didn't make it out."[2]

He attended John H. Francis Polytechnic High School, and transferred to San Fernando Valley State College (now California State University, Northridge) in 1969 before completing his senior year of high school. Palast said about high school: "Basically they were melting my brain, and I had to save myself. Before I finished high school, I talked my way into college. Before I finished college, I talked my way into graduate school."[1] Palast then attended the University of California, Los Angeles, University of California, Berkeley, and University of Chicago, from which he graduated in 1974 with a Bachelor of Arts in economics and in 1976 with a Master's of Business Administration. Palast majored in economics at Chicago from the advice of a Weather Underground member he met at Berkeley who suggested Palast "familiarize himself with right-wing politics and learn about the 'ruling elite' from 'the inside.'"[1]

Career

[edit]Since 2000, Greg Palast has made more than a dozen films for the BBC program Newsnight with the Investigations Producer Meirion Jones, which have been broadcast in the UK and worldwide. In addition to the films on US elections they have investigated oil companies, the Iraq War, the attempted coup against Hugo Chávez, and the vulture funds which target the poorest countries.

Palast spoke at a Think Twice conference held at Cambridge University[3] and lectured at the University of São Paulo.[4]

Presidential elections

[edit]Palast's investigation into the Bush family fortunes for his column in The Observer led him to uncover a connection to a company called ChoicePoint. In an October 2008 interview Palast said that before the 2000 election, ChoicePoint "was purging the voter rolls of Florida under a contract with a lady named Katherine Harris, the Secretary of State. They won a contract, a bid contract with the state, with the highest bid."[5] After subsequently noticing a large proportion of African-American voters were claiming their names had disappeared from voter rolls in Florida in the 2000 election, Palast launched a full-scale investigation into election fraud, the results of which were broadcast in the UK by the BBC on their Newsnight[6] show prior to the 2004 election. Palast claimed to have obtained computer discs from Katherine Harris' office, which contained caging lists of "voters matched by race and tagged as felons."[5] Palast appeared in the 2003 documentary film, Florida Fights Back! Resisting the Stolen Election, along with Vincent Bugliosi, former Los Angeles Deputy District Attorney and author of The Betrayal of America. Palast also appeared in the 2004 documentary Orwell Rolls in His Grave, which focuses on the hidden mechanics of the media.[citation needed]

In May 2007, Palast said he'd received 500 emails that former White House Deputy Chief of Staff Karl Rove exchanged through an account supplied by the Republican National Committee. Palast says the emails show a plan to target likely Democratic voters with extra scrutiny over their home addresses, and he also believes Rove's plan was a factor in the firing of U.S. Attorneys.[7]

After Palast was invited by Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to appear on his Air America talk show to discuss, among other things, election fraud, the pair teamed up to publish a report in October 2008 in Rolling Stone, concluding that the 2008 election had already been stolen. "If Democrats are to win the 2008 election, they must not simply beat John McCain at the polls -- they must beat him by a margin that exceeds the level of GOP vote tampering", Palast and Kennedy summarized.[8] To combat the extensive acts of voter suppression that Palast and Kennedy uncovered, the duo launched a campaign called Steal Back Your Vote,[9] which features a website and free downloadable voter guide / adult comic book.

Palast has conducted a multi-year investigation into Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach's Interstate Voter Registration Crosscheck Program (commonly referred to as "Crosscheck"). The program utilizes states' voter registration lists to match possible "double voters," using their first and last names and the last four digits of their Social Security number. In 2014, Palast investigated Crosscheck for Al Jazeera America, finding that the program was inherently biased toward removing minority voters from states' voter rolls. In 2016, he followed up with a documentary film, The Best Democracy Money Can Buy, along with an article. [10]

Energy companies

[edit]In 1988, Palast directed a U.S. civil racketeering investigation into the Shoreham Nuclear Power Station project, under construction by Stone & Webster and Long Island Lighting Company. A jury awarded the plaintiffs US$4.8 billion; however, New York's federal judge Jack B. Weinstein, reversed the verdict, and the case was later settled for $400 million.[11] The racketeering charges stemmed from an accusation that LILCO filed false documents in order to secure rate increases. LILCO sought a dismissal of these charges on the grounds that Suffolk County lacked authority under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act and that the allegations of a history of racketeering did not qualify as a continuing criminal enterprise.[12]

Palast has also taken issue with the official story behind the grounding of the Exxon Valdez, claiming the sobriety of the Valdez's captain was not an issue in the accident. According to Palast, the main cause of the Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 was not human error, but an Exxon decision not to use the ship's radar in order to save money. The Raytheon Raycas radar system would not have detected Bligh Reef itself - as radar, unlike sonar, is incapable of detecting submerged objects. The radar system would have detected the radar reflector, placed on the next rock inland from Bligh Reef for the purpose of keeping vessels on course via radar.[13] Palast points out that the original owners of the land, the local Alaska Natives tribe, took only one dollar in payment for the land with a promise not to pollute it and spoil their fishing and seal hunting grounds.[13]

In An Open Letter to Greg Palast on Peak Oil[14] Richard Heinberg offers friendly criticism of Palast, saying he conflates the "amount of oil left" with "peak (maximal) flow rates" for oil, the latter being key to the Peak Oil concept.

On October 27, 2010, Palast wrote, "The Petroleum Broadcast System Owes Us an Apology. ... BP has neglected warnings about oil safety for years! ... But so has PBS. The Petroleum Broadcast System has turned a blind eye to BP perfidy for decades. If the broadcast had come six months before the Gulf blow-out, after [major accidents in 2005 and 2006 or after years of government fines], I would say, “Damn, that Frontline sure is courageous.” But six months after the blow-out, PBS has shown us it only has the courage to shoot the wounded. ... The entire hour told us again and again and again, the problem was one company, BP, and its 'management culture.' ... Unlike Shell Oil’s culture which has turned Nigeria into a toxic cesspool; unlike ExxonMobil’s culture which remains in denial about the horror it heaped on Alaska. And unlike Chevron’s culture, which I witnessed in the Amazon. Chevron culture left Ecuadoran farmers with pustules all over their bodies and a graveyard of children dead of leukemia.[15]

"LobbyGate" scandal

[edit]In 1998, working as an undercover reporter for The Observer, Palast, posing as an American businessman with ties to Enron, caught on tape two Labour party insiders, Derek Draper and Jonathan Mendelsohn, boasting about how they could sell access to government ministers, obtain advance copies of sensitive reports, and create tax breaks for their clients.[16]

Draper denied the allegations.[17] At Prime Minister's Question Time July 8, 1998 British Prime Minister Tony Blair claimed that all the specific claims had been investigated and found groundless: "every allegation made in The Observer has been investigated and found to be untrue".[18]

Vulture funds

[edit]Starting in 2007 Palast published a series of investigations on what aid groups and investors call "vulture funds". A vulture fund is a private equity or hedge fund where companies or people buy the debt of a poor country and litigate to recover the funds, often at the expense of aid and debt relief. Prime Minister Gordon Brown commented on the practices saying "We particularly condemn the perversity where Vulture Funds purchase debt at a reduced price and make a profit from suing the debtor country to recover the full amount owed - a morally outrageous outcome".[19]

In 2014 Palast detailed the workings of vulture funds during the crisis of the American automotive industry:

Singer, through a brilliantly complex financial manoeuvre, took control of Delphi Automotive, the sole supplier of most of the auto parts needed by General Motors and Chrysler. Both auto firms were already in bankruptcy. Singer and co-investors demanded the US Treasury pay them billions, including $350m (£200m) in cash immediately, or – as the Singer consortium threatened – "we'll shut you down" by ending GM's supply of parts. GM and Chrysler, with only a few days' worth of parts in stock, would have shut down and permanently forced into liquidation. Obama's negotiator, Treasury deputy Steven Rattner, called the vulture funds' demand "extortion" ... Ultimately, the US Treasury quietly paid the Singer consortium a cool $12.9bn in cash and subsidies from the US Treasury's auto bailout fund. Singer responded to Obama's largesse by quickly shutting down 25 of Delphi's 29 US auto parts plants, shifting 25,000 jobs to Asia. Singer's Elliott Management pocketed $1.29bn of which Singer personally garnered the lion's share.

— Palast 2014[20]

2024 US presidential election suppression

[edit]In January 2025, Palast wrote an article for The Hartmann Report in which he claimed that Donald Trump lost the 2024 United States presidential election.[21] His claims were also repeated on his personal investigative journalism website and Thom Hartmann's podcast.[22][23] He asserted that if all legal ballots had been counted in Georgia, Pennsylvania, Michigan and Wisconsin then Kamala Harris would have won the election, attributing her loss to voter suppression, which he compared to Jim Crow, as well as restrictive state voting laws, explaining that the rejection of a postal vote was 400% more likely to occur if the voter was Black.[21]

The methods of voter suppression he outlined included vote purging, a legal process usually used to clean up voter rolls by deleting people from registration lists, voter challenges, the disqualification of ballots for minor clerical errors, the rejection of provisional ballots, and the disproportionately high vote rejection rates for Black voters.[24] According to Palast, the Election Assistance Commission stated that 4,776,706 voters were wrongfully purged. He linked the voter challenges to "vigilante" vote-fraud hunters who targeted people to challenge and block the counting of their ballots, claims he previously made in his documentary Vigilantes Inc.[25] He claimed that by August 2024, the rights of 317,886 voters were challenged with over 200,000 challenges occurring in Georgia.

Works

[edit]Books

[edit]- The Best Democracy Money Can Buy. London: Pluto Press. 2002. ISBN 0-452-28391-4.

- Greg Palast; Jerrold Oppenheim; Theo MacGregor (2003). Democracy and regulation : how the public can govern essential services. Pluto Press. ISBN 0-7453-1943-2. LCCN 2002015669. Wikidata Q132171022.

- Armed Madhouse. New York, NY: Dutton. 2006. ISBN 0-525-94968-2.[26]

- Vultures' Picnic. New York: Dutton. 2011. ISBN 978-0-525-95207-7.[27]

- Billionaires and Ballot Bandits: How to Steal an Election in 9 Easy Steps. New York: Seven Stories Press. 2012. ISBN 978-1-609-80478-7.[28]

- The Best Democracy Money Can Buy: A Tale of Billionaires & Ballot Bandits. New York: Seven Stories Press. 2016. ISBN 978-1609807757.[29]

- How Trump Stole 2020. New York: Seven Stories Press. 2020. ISBN 978-1644210567.

Films

[edit]- Bush Family Fortunes: The Best Democracy Money Can Buy. 2004.[30][31]

- American Blackout. 2006.

- Big Easy to Big Empty [Pt 1],[32] [Pt 2].[33] 2007.

- The Election Files. 2009.[34][35]

- Palast Investigates. 2010.[36][37]

- The Best Democracy Money Can Buy (2016).[38][39]

- Vigilante: Georgia's Vote Suppression Hitman 2022

- Vigilante Inc.: America's New Vote Suppression Hitmen 2024

Newsnight

[edit]- "Microsoft" (2000)[40]

- "US Election 2000" (2001)[41]

- "Bush dances with Enron" (2001)[42]

- "Bush and the Bin Ladens" (2001)[43]

- "Stiglitz" (2001)[44]

- "Chavez and the Coup" (2002)[45]

- "Iraq – Jay Garner's story" (2004)[46]

- "US Election 2004" (2004)[47]

- "Secret US plans for Iraq's oil" (2005)[48]

- "Chavez and Oil" (2006)[49]

- "Vulture Funds attack Zambia" (2007)[50]

- "Tim Griffin" (2007)[51]

- "Bush and the Vultures" (2007)[52]

- "Chevron and Ecuador" (2007)[53]

- "US Election 2008" (2008)[54]

- "Vulture Funds attack Liberia" (2010)[55]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Greg Palast" (PDF). Current Biography. June 2011. pp. 73–80. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 28, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ^ San Francisco Chronicle, December 7, 2007

- ^ "Think Twice 2002: list of speakers". Think Twice Conference at Cambridge University. Archived from the original on September 13, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- ^ "Currículo do Sistema de Currículos Lattes (Ildo Luis Sauer)". University of São Paulo. Archived from the original on July 17, 2007. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- ^ a b "Greg Palast: Steal Back Your Vote". suicidegirls.com. October 27, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ Palast, Greg (October 26, 2004). "New Florida vote scandal feared". BBC News. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ Diehl, Jeff (May 24, 2007). "The Future of America Has Been Stolen". 10zenmonkeys.com.

- ^ "Block the Vote". Rolling Stone. October 23, 2008. Archived from the original on October 20, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ "Steal Back Your Vote". stealbackyourvote.org. October 1, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2008.

- ^ The GOP's Stealth War Against Voters Archived September 3, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Rolling Stone, Greg Palast, August 24, 2016. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ THE RISE AND FALL OF LILCO'S NUCLEAR POWER PROGRAM, THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL JOURNAL, Karl Grossman, Fall 1992. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

- ^ "Lilco Loses Bid to Dismiss Suit Charging Racketeering". The New York Times. May 19, 1988.

- ^ a b Palast, Gregory (March 29, 1999). "Don't Buy Exxon's Fable Of The Drunken Captain". The Guardian. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ Heinberg, Richard (July 6, 2006). "An Open Letter to Greg Palast on Peak Oil". Energy Bulletin. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ Palast, Greg (October 27, 2010). "The Petroleum Broadcast System Owes Us an Apology". Gregpalast.com. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Greg Palast (May 1, 2005). "Britain for Sale". Retrieved November 29, 2007.

- ^ "Draper accuses Observer of entrapment". BBC. July 7, 1998. Retrieved November 29, 2007.

- ^ "Prime Minister's Questions". Hansard. July 8, 1998. Retrieved November 29, 2007.

- ^ "Vulture Fund Threat to Third World". BBC Newsnight via GregPalast.com. February 14, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ Greg Palast (August 7, 2014). "Obama Can End Argentina's Debt Crisis with a Pen". The Guardian.

- ^ a b Greg Palast (January 25, 2025). "TRUMP LOST. Vote Suppression Won". The Hartmann Report. Archived from the original on January 25, 2025. Retrieved January 30, 2025.

- ^ Palast, Gregory (January 24, 2025). "Trump Lost. Vote Suppression Won". Greg Palast. Archived from the original on January 26, 2025. Retrieved January 27, 2025.

- ^ Thom Hartmann Program (January 27, 2025). "Shocking Proof: Trump's VICTORY WAS RIGGED Through Voter Suppression! w/ Greg Palast". Youtube. Retrieved January 30, 2025.

- ^ Brennan center for justice. "Voter Purges". BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE. Retrieved January 30, 2025.

- ^ Greg Palast (October 18, 2024). "Vigilantes Inc". Youtube. Retrieved January 30, 2025.

- ^ Interview with Greg Palast about his new book: Armed Madhouse Archived November 15, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, democracynow.org

- ^ Vultures' Picnic Book Website, VulturesPicnic.org

- ^ Billionaires and Ballot Bandits Book Website Archived August 19, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, BallotBandits.org

- ^ Palast Investigative Fund Book Page, PalastInvestigativeFund.org

- ^ "Bush Family Fortunes (2003)". Gregpalast.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "Bush Family Fortunes". Gregpalast.com. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Big Easy to Big Empty". YouTube. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Part 2- Big Easy to Big Empty". YouTube. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "The Election Files (2009)". Gregpalast.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "Palast Investigative Fund Store". Gregpalast.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "Palast Investigates (2010)". Gregpalast.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2011. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "Palast Investigative Fund Store". Gregpalast.com. Archived from the original on December 8, 2011. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ "The Best Democracy Money Can Buy (2016)". Gregpalast.com. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ "The Best Democracy Money Can Buy". Gregpalast.com. Retrieved November 11, 2016.

- ^ Millions may be eligible for Microsoft refund, gregpalast.com

- ^ Newsnight: Greg Palast on the Florida Elections - 16/2/01, BBC NEWS

- ^ Newsnight: Payback transcript - 17/5/01, BBC NEWS

- ^ Newsnight: Greg Palest report transcript - 6/11/01, BBC NEWS

- ^ World Bank creating poverty (BBC Newsnight)

- ^ Warning to Venezuelan leader, BBC NEWS

- ^ Newsnight: General Jay Garner, BBC NEWS

- ^ Newsnight: New Florida vote scandal feared, BBC NEWS

- ^ Newsnight: Secret US plans for Iraq's oil, BBC NEWS

- ^ Chavez rules out return to cheap oil, BBC NEWS

- ^ Newsnight: 'Vulture funds' threat to developing world, BBC News

- ^ US Attorney Resigns Following Conyers' Request for BBC Documents

- ^ "Greg Palast on the Battle to End Vulture Funds". Democracy Now. June 11, 2007. Retrieved December 16, 2011.

- ^ Newsnight: Amazon natives sue oil giant, BBC NEWS

- ^ Newsnight October 7, 2008 - Greg Palast on US elections 1 of 2 on YouTube

- ^ Liberian leader urges MPs to back action against vulture funds, The Guardian

External links

[edit]- GregPalast.com - 'The Writings of Greg Palast' (official website)

- GregPalastOffice - Greg Palast's YouTube page

- Greg Palast at IMDb

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Election 2004 Shoplifting the Presidency? - interview on Democracy Now!

- Scoop.co.nz - 'OPEC & The Economic Conquest Of Iraq', Greg Palast

- New York Inquirer interview with Greg Palast

- Palast article 'On the 2006 Mid-Term Elections'

- "A Sleeper Cell of Rove-Bots" - May 24, 2007 interview

- Greg Palast Tracks Vulture Funds Preying on African Debt - Video report by Democracy Now!

- "Save My Vote 2020", SaveMyVote2020.org, Los Angeles, CA: Palast Investigative Fund, archived from the original on September 30, 2023, retrieved October 12, 2020,

Purged? Check if your voter registration has been cancelled