Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

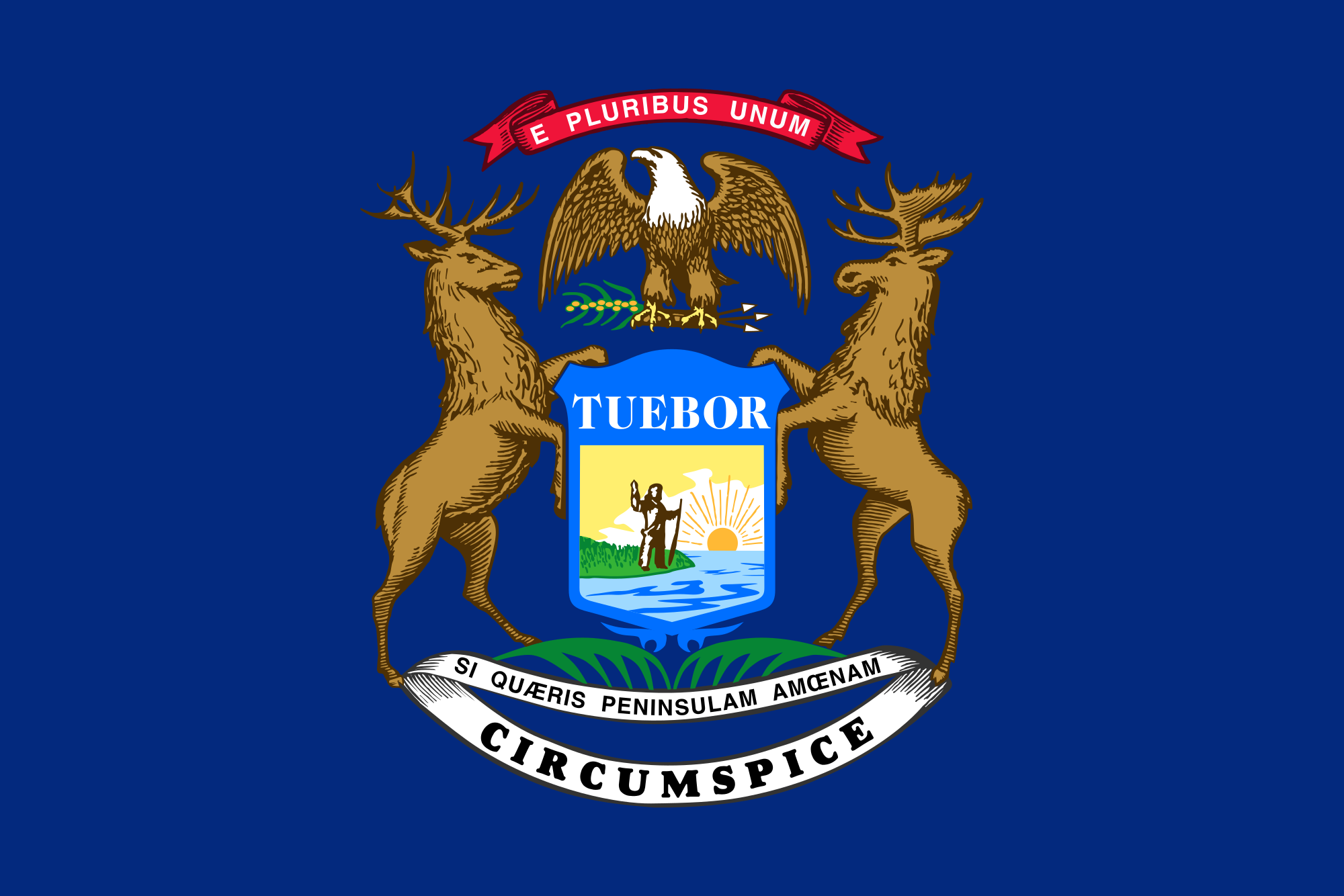

Michigan

View on Wikipedia

Michigan (/ˈmɪʃɪɡən/ ⓘ MISH-ig-ən) is a peninsular state in the Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, Indiana and Illinois to the southwest, Ohio to the southeast, and the Canadian province of Ontario to the east, northeast and north. With a population of 10.14 million[3] and an area of 96,716 sq mi (250,490 km2), Michigan is the tenth-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the largest by total area east of the Mississippi River.[b] The state capital is Lansing, while its most populous city is Detroit. The Metro Detroit region in Southeast Michigan is among the nation's most populous and largest metropolitan economies. Other important metropolitan areas include Grand Rapids, Flint, Ann Arbor, Kalamazoo, the Tri-Cities, and Muskegon.

Key Information

Michigan consists of two peninsulas: the heavily forested Upper Peninsula (commonly called "the U.P."), which juts eastward from northern Wisconsin, and the more populated Lower Peninsula, stretching north from Ohio and Indiana. The peninsulas are separated by the Straits of Mackinac, which connects Lake Michigan and Lake Huron, and are linked by the 5-mile-long Mackinac Bridge along Interstate 75. Bordering four of the five Great Lakes and Lake St. Clair, Michigan has the longest freshwater coastline of any U.S. political subdivision, measuring 3,288 miles.[5] The state ranks second behind Alaska in water coverage by square miles and first in percentage, with approximately 42%, and it also contains 64,980 inland lakes and ponds.[6][7]

The Great Lakes region has largely been inhabited for thousands of years by Indigenous peoples such as the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, and Wyandot. Some people contend that the region's name is derived from the Ojibwe word ᒥᓯᑲᒥ (mishigami),[c] meaning "large water" or "large lake".[1][8] While others say that it comes from the Mishiiken Tribe of Mackinac Island, also called Michinemackinawgo by Ottawa historian Andrew Blackbird,[9] whose surrounding lands were referred to as Mishiiken-imakinakom, later shortened to Michilimackinac.

In the 17th century, French explorers claimed the area for New France. French settlers and Métis established forts and settlements. After France's defeat in the French and Indian War in 1762, the area came under British control and later the U.S. following the Treaty of Paris (1783), though control remained disputed with Indigenous tribes until treaties between 1795 and 1842. The area was part of the larger Northwest Territory; the Michigan Territory was organized in 1805.

Michigan was admitted as the 26th state on January 26, 1837, entering as a free state and quickly developing into an industrial and trade hub that attracted European immigrants, particularly from Finland, Macedonia, and the Netherlands.[10] In the 1930s, migration from Appalachia and the Middle East and the Great Migration of Black Southerners further shaped the state, especially in Metro Detroit.[11][12]

Michigan has a diversified economy with a gross state product of $725.897 billion as of Q1 2025, ranking 14th among the 50 states.[13] Although the state has developed a diverse economy, in the early 20th century it became widely known as the center of the U.S. automotive industry, which developed as a major national economic force. It is home to the country's three major automobile companies (whose headquarters are all in Metro Detroit). Once exploited for logging and mining, today the sparsely populated Upper Peninsula is important for tourism because of its abundance of natural resources.[14][15] The Lower Peninsula is a center of manufacturing, forestry, agriculture, services, and high-tech industry.

History

[edit]When the first European explorers arrived, the most populous tribes were the Algonquian peoples, which include the Anishinaabe groups of Ojibwe, Odaawaa/Odawa (Ottawa), and the Boodewaadamii/Bodéwadmi (Potawatomi). The three nations coexisted peacefully as part of a loose confederation called the Council of Three Fires. The Ojibwe, whose numbers are estimated to have been at least 35,000, were the largest.[16]

The Ojibwe Indians (also known as Chippewa in the U.S.), an Anishinaabe tribe, were established in Michigan's Upper Peninsula and northern and central Michigan. Bands also inhabited Ontario and southern Manitoba, Canada; and northern Wisconsin, and northern and north-central Minnesota. Smaller groups of Algonquian Indians like the Noquet in the Upper Peninsula were present for thousands of years but subsequently absorbed by neighboring tribes before and during European contact.[17] The Ottawa Indians lived primarily south of the Straits of Mackinac in northern, western, and southern Michigan, but also in southern Ontario, northern Ohio, and eastern Wisconsin. The Potawatomi were in southern and western Michigan, in addition to northern and central Indiana, northern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, and southern Ontario. Other Algonquian tribes in Michigan, in the south and east, were the Mascouten, the Menominee, the Miami, the Sac (or Sauk), and the Meskwaki (Fox). The Wyandot were an Iroquoian-speaking people in this area; they were historically known as the Huron by the French, and were the historical adversaries of the Iroquois Confederation.[18]

17th century

[edit]

French voyageurs and coureurs des bois explored and settled in Michigan in the 17th century. The first Europeans to reach what became Michigan were those of Étienne Brûlé's expedition in 1622. The first permanent European settlement was founded in 1668 on the site where Père Jacques Marquette established Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, as a base for Catholic missions.[19][20] Missionaries in 1671–75 founded outlying stations at Saint Ignace and Marquette. Jesuit missionaries were well received by the area's Indian populations, with few difficulties or hostilities. In 1679, Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle built Fort Miami at present-day St. Joseph. In 1691, the French established a trading post and Fort St. Joseph along the St. Joseph River at the present-day city of Niles.

18th century

[edit]In 1701, French explorer and army officer Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac founded Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit or "Fort Pontchartrain on-the-Strait" on the strait, known as the Detroit River, between lakes Saint Clair and Erie.[citation needed] Cadillac had convinced Louis XIV's chief minister, Louis Phélypeaux, Comte de Pontchartrain, that a permanent community there would strengthen French control over the upper Great Lakes and discourage British aspirations.[citation needed]

The hundred soldiers and workers who accompanied Cadillac built a fort enclosing one arpent (about 0.85 acres (3,400 m2),[21][22] the equivalent of just under 200 feet (61 m) per side) and named it Fort Pontchartrain. Cadillac's wife, Marie Thérèse Guyon, soon moved to Detroit, becoming one of the first European women to settle in what was considered the wilderness of Michigan. The town quickly became a major fur-trading and shipping post. The Église de Saint-Anne (Catholic Church of Saint Anne) was founded the same year.[citation needed] While the original building does not survive, the congregation remains active.[citation needed] Cadillac later departed to serve as the French governor of Louisiana from 1710 to 1716.[citation needed] French attempts to consolidate the fur trade led to the Fox Wars, in which the Meskwaki (Fox) and their allies fought the French and their Native allies.[citation needed]

At the same time, the French strengthened Fort Michilimackinac at the Straits of Mackinac to better control their lucrative fur-trading empire. By the mid-18th century, the French also occupied forts at present-day Niles and Sault Ste. Marie, though most of the rest of the region remained unsettled by Europeans. France offered free land to attract families to Detroit, which grew to 800 people in 1765. It was the largest city between Montreal and New Orleans.[23] French settlers also established small farms south of the Detroit River opposite the fort, near a Jesuit mission and Huron village.

From 1660 until the end of French rule, Michigan was part of the Royal Province of New France.[d] In 1760, Montreal fell to the British forces, ending the French and Indian War (1754–1763), the North American front of the Seven Years' War in Europe. Under the 1763 Treaty of Paris, Michigan and the rest of New France east of the Mississippi River were ceded by defeated France to Great Britain.[24] After the Quebec Act was passed in 1774, Michigan became part of the British Province of Quebec. By 1778, Detroit's population reached 2,144 and it was the third-largest city in Quebec province.[25]

During the American Revolutionary War, Detroit was an important British supply center. Most of the inhabitants were French-Canadians or American Indians, many of whom had been allied with the French because of long trading ties. Because of imprecise cartography and unclear language defining the boundaries in the 1783 Treaty of Paris, the British retained control of Detroit and Michigan after the American Revolution. When Quebec split into Lower and Upper Canada in 1791, Michigan was part of Kent County, Upper Canada. It held its first democratic elections in August 1792 to send delegates to the new provincial parliament at Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake).[26]

Under terms negotiated in the 1794 Jay Treaty, Britain withdrew from Detroit and Michilimackinac in 1796. It retained control of territory east and south of the Detroit River, which are now included in Ontario, Canada. Questions remained over the boundary for many years, and the United States did not have uncontested control of the Upper Peninsula and Drummond Island until 1818 and 1847, respectively.

19th century

[edit]During the War of 1812, the United States forces at Fort Detroit surrendered Michigan Territory (effectively consisting of Detroit and the surrounding area) after a nearly bloodless siege in 1812. A U.S. attempt to retake Detroit resulted in a severe American defeat in the River Raisin Massacre. This battle, still ranked as the bloodiest ever fought in the state, had the highest number of American casualties of any battle of the war.

Michigan was recaptured by the Americans in 1813 after the Battle of Lake Erie. They used Michigan as a base to launch an invasion of Canada, which culminated in the Battle of the Thames. But the more northern areas of Michigan were held by the British until the peace treaty restored the old boundaries. A number of forts, including Fort Wayne, were built by the United States in Michigan during the 19th century out of fears of renewed fighting with Britain.

Michigan Territory governor and judges established the University of Michigan in 1817, as the Catholepistemiad, or the University of Michigania.[27]

The population grew slowly until the opening in 1825 of the Erie Canal through the Mohawk Valley in New York, connecting the Great Lakes to the Hudson River and New York City.[28] The new route attracted a large influx of settlers to the Michigan territory. They worked as farmers, lumbermen, shipbuilders, and merchants and shipped out grain, lumber, and iron ore. By the 1830s, Michigan had 30,000 residents, more than enough to apply and qualify for statehood.[29]

On November 1, 1935, the U.S. Post Office issued a commemorative 3-cent stamp celebrating the 100th anniversary of Michigan statehood. Michigan's statehood, however, wasn't officially established until January 26, 1837, but since the campaign for statehood actually began in 1835, Michigan chose to hold its centennial celebration in 1935, the year the stamp was first issued.[30]

A constitutional convention of assent was held to lead the territory to statehood.[31] In October 1835 the people approved the constitution of 1835, thereby forming a state government. Congressional recognition was delayed pending resolution of a boundary dispute with Ohio known as the Toledo War. Congress awarded the "Toledo Strip" to Ohio. Michigan received the western part of the Upper Peninsula as a concession and formally entered the Union as a free state on January 26, 1837. The Upper Peninsula proved to be a rich source of lumber, iron, and copper. Michigan led the nation in lumber production from the 1850s to the 1880s. Railroads became a major engine of growth from the 1850s onward, with Detroit the chief hub.

A second wave of French-Canadian immigrants settled in Michigan during the late 19th to early 20th century, working in lumbering areas in counties on the Lake Huron side of the Lower Peninsula, such as the Saginaw Valley, Alpena, and Cheboygan counties, as well as throughout the Upper Peninsula, with large concentrations in Escanaba and the Keweenaw Peninsula.[32]

The first statewide meeting of the Republican Party took place on July 6, 1854, in Jackson, Michigan, where the party adopted its platform.[33][34] The state was predominantly Republican until the 1930s, reflecting the political continuity of migrants from across the Northern Tier of New England and New York.[citation needed] Michigan made a significant contribution to the Union in the American Civil War and sent more than forty regiments of volunteers to the federal armies.[citation needed]

Michigan modernized and expanded its system of education in this period.[citation needed] The Michigan State Normal School, now Eastern Michigan University, was founded in 1849, for the training of teachers.[35] It was the fourth oldest normal school in the United States and the first U.S. normal school outside New England.[citation needed] In 1899, the Michigan State Normal School became the first normal school in the nation to offer a four-year curriculum. Michigan Agricultural College (1855), now Michigan State University in East Lansing, was founded as the first agricultural college in the nation.[citation needed] Many private colleges were founded as well, and the smaller cities established high schools late in the century.[36]

20th–21st centuries

[edit]

Michigan's economy underwent a transformation at the turn of the 20th century. Many individuals, including Ransom E. Olds, John and Horace Dodge, Henry Leland, David Dunbar Buick, Henry Joy, Charles King, and Henry Ford, provided the concentration of engineering know-how and technological enthusiasm to develop the automotive industry.[37] Ford's development of the moving assembly line in Highland Park marked a new era in transportation.[citation needed] Like the steamship and railroad, mass production of automobiles was a far-reaching development. More than the forms of public transportation, the affordable automobile transformed private life. Automobile production became the major industry of Detroit and Michigan, and permanently altered the socioeconomic life of the United States and much of the world.[citation needed]

With the growth, the auto industry created jobs in Detroit that attracted immigrants from Europe and migrants from across the United States, including both blacks and whites from the rural South.[citation needed] By 1920, Detroit was the fourth-largest city in the U.S..[citation needed] Residential housing was in short supply, and it took years for the market to catch up with the population boom.[citation needed] By the 1930s, so many immigrants had arrived that more than 30 languages were spoken in the public schools, and ethnic communities celebrated in annual heritage festivals.[38] Over the years immigrants and migrants contributed greatly to Detroit's diverse urban culture, including popular music trends. The influential Motown Sound of the 1960s was led by a variety of individual singers and groups.[citation needed]

Grand Rapids, the second-largest city in Michigan, also became an important center of manufacturing. Since 1838, the city has been noted for its furniture industry.[39][40] In the 21st century, it is home to five of the world's leading office furniture companies. Grand Rapids is home to a number of major companies including Steelcase, Amway, and Meijer. Grand Rapids is also an important center for GE Aviation Systems.

Michigan held its first United States presidential primary election in 1910.[citation needed] With its rapid growth in industry, it was an important center of industry-wide union organizing, such as the rise of the United Auto Workers.[citation needed]

In 1920 WWJ (AM) in Detroit became the first radio station in the United States to regularly broadcast commercial programs. Throughout that decade, some of the country's largest and most ornate skyscrapers were built in the city. Particularly noteworthy are the Fisher Building, Cadillac Place, and the Guardian Building, each of which has been designated as a National Historic Landmark (NHL).

In 1927 a school bombing took place in Clinton County. The Bath School disaster resulted in the deaths of 38 schoolchildren and constitutes the deadliest mass murder in a school in U.S. history.[41]

Michigan converted much of its manufacturing to satisfy defense needs during World War II; it manufactured 10.9% of the United States military armaments produced during the war, ranking second (behind New York) among the 48 states.[42]

Detroit continued to expand through the 1950s, at one point doubling its population in a decade. After World War II, housing was developed in suburban areas outside city cores to meet demand for residences. The federal government subsidized the construction of interstate highways, which were intended to strengthen military access, but also allowed commuters and business traffic to travel the region more easily. Since 1960, modern advances in the auto industry have led to increased automation, high-tech industry, and increased suburban growth. Longstanding tensions in Detroit culminated in the Twelfth Street riot in July 1967.

During the late 1970s and the early 1980s, increasing fuel costs and other factors made significantly more global competition and recession among families. Michigan lost a significant amount of population due to global competition and the dramatic unavailability of manufacturing jobs.[43] Meanwhile, Michigan had increased use of technology, specifically when the IBM Personal Computer started selling in the state, in which became mostly used at work.

Michigan became the leading auto-producing state in the U.S., with the industry primarily located throughout the Midwestern United States; Ontario, Canada; and the Southern United States.[44] With almost ten million residents in 2010, Michigan is a large and influential state, ranking tenth in population among the fifty states. Detroit is the centrally located metropolitan area of the Great Lakes megalopolis and the second-largest metropolitan area in the U.S. (after Chicago) linking the Great Lakes system.

The Metro Detroit area in Southeast Michigan is the state's largest metropolitan area (roughly 50% of the population resides there) and the eleventh largest in the United States. The Grand Rapids metropolitan area in Western Michigan is the state's fastest-growing metro area, with more than 1.3 million residents as of 2006[update].

Geography

[edit]

Michigan consists of two peninsulas separated by the Straits of Mackinac. The 45th parallel north runs through the state, marked by highway signs and the Polar-Equator Trail—[45] along a line including Mission Point Light near Traverse City, the towns of Gaylord and Alpena in the Lower Peninsula and Menominee in the Upper Peninsula. With the exception of two tiny areas drained by the Mississippi River by way of the Wisconsin River in the Upper Peninsula and by way of the Kankakee-Illinois River in the Lower Peninsula, Michigan is drained by the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence watershed and is the only state with the majority of its land thus drained. No point in the state is more than six miles (9.7 km) from a natural water source or more than 85 miles (137 km) from a Great Lakes shoreline.[46]

The Great Lakes that border Michigan from east to west are Lake Erie, Lake Huron, Lake Michigan and Lake Superior. The state is bounded on the south by the states of Ohio and Indiana, sharing land and water boundaries with both. Michigan's western boundaries are almost entirely water boundaries, from south to north, with Illinois and Wisconsin in Lake Michigan; then a land boundary with Wisconsin and the Upper Peninsula, that is principally demarcated by the Menominee and Montreal Rivers; then water boundaries again, in Lake Superior, with Wisconsin and Minnesota to the west, capped around by the Canadian province of Ontario to the north and east.

The heavily forested Upper Peninsula is relatively mountainous in the west. The Porcupine Mountains, which are part of one of the oldest mountain chains in the world,[47] rise to an altitude of almost 2,000 feet (610 m) above sea level and form the watershed between the streams flowing into Lake Superior and Lake Michigan. The surface on either side of this range is rugged. The state's highest point, in the Huron Mountains northwest of Marquette, is Mount Arvon at 1,979 feet (603 m). The peninsula is as large as Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island combined but has fewer than 330,000 inhabitants. The people are sometimes called "Yoopers" (from "U.P.'ers"), and their speech (the "Yooper dialect") has been heavily influenced by the numerous Scandinavian and Canadian immigrants who settled the area during the lumbering and mining boom of the late 19th century.

The Lower Peninsula is shaped like a mitten and many residents hold up a hand to depict where they are from.[48] It is 277 miles (446 km) long from north to south and 195 miles (314 km) from east to west and occupies nearly two-thirds of the state's land area. The surface of the peninsula is generally level, broken by conical hills and glacial moraines usually not more than a few hundred feet tall. It is divided by a low water divide running north and south. The larger portion of the state is on the west of this and gradually slopes toward Lake Michigan. The highest point in the Lower Peninsula is either Briar Hill at 1,705 feet (520 m), or one of several points nearby in the vicinity of Cadillac. The lowest point is the surface of Lake Erie at 571 feet (174 m).

The geographic orientation of Michigan's peninsulas makes for a long distance between the ends of the state. Ironwood, in the far western Upper Peninsula, lies 630 miles (1,010 kilometers) by highway from Lambertville in the Lower Peninsula's southeastern corner. The geographic isolation of the Upper Peninsula from Michigan's political and population centers makes the region culturally and economically distinct. Frequent attempts to establish the Upper Peninsula as its own state have failed to gain traction.[49][50]

A feature of Michigan that gives it the distinct shape of a mitten is the Thumb, which projects into Lake Huron, forming Saginaw Bay. Other notable peninsulas of Michigan include the Keweenaw Peninsula, which projects northeasterly into Lake Superior from the Upper Peninsula and largely comprising Michigan's Copper Country region, and the Leelanau Peninsula, projecting from the Lower Peninsula into Lake Michigan, forming Michigan's "little finger".

Numerous lakes and marshes mark both peninsulas, and the coast is much indented. Keweenaw Bay, Whitefish Bay, and the Big and Little Bays De Noc are the principal indentations on the Upper Peninsula. The Grand and Little Traverse, Thunder, and Saginaw bays indent the Lower Peninsula. Michigan has the second longest shoreline of any state—3,288 miles (5,292 km),[51] including 1,056 miles (1,699 km) of island shoreline.[52]

The state has numerous large islands, the principal ones being the North Manitou and South Manitou, Beaver, and Fox groups in Lake Michigan; Isle Royale and Grande Isle in Lake Superior; Marquette, Bois Blanc, and Mackinac islands in Lake Huron; and Neebish, Sugar, and Drummond islands in St. Mary's River. Michigan has about 150 lighthouses, the most of any U.S. state.[53] The first lighthouses in Michigan were built between 1818 and 1822. They were built to project light at night and to serve as a landmark during the day to safely guide the passenger ships and freighters traveling the Great Lakes (see: lighthouses in the United States).

The state's rivers are generally small, short and shallow, and few are navigable. The principal ones include the Detroit River, St. Marys River, and St. Clair River which connect the Great Lakes; the Au Sable, Cheboygan, and Saginaw, which flow into Lake Huron; the Ontonagon, and Tahquamenon, which flow into Lake Superior; and the St. Joseph, Kalamazoo, Grand, Muskegon, Manistee, and Escanaba, which flow into Lake Michigan. The state has 11,037 inland lakes—totaling 1,305 square miles (3,380 km2) of inland water—in addition to 38,575 square miles (99,910 km2) of Great Lakes waters. No point in Michigan is more than six miles (9.7 km) from an inland lake or more than 85 miles (137 km) from one of the Great Lakes.[54]

The state is home to several areas maintained by the National Park Service including: Isle Royale National Park, in Lake Superior, about 30 miles (48 km) southeast of Thunder Bay, Ontario. Other national protected areas in the state include: Keweenaw National Historical Park, Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Huron National Forest, Manistee National Forest, Hiawatha National Forest, Ottawa National Forest and Father Marquette National Memorial. The largest section of the North Country National Scenic Trail passes through Michigan.

With 78 state parks, 19 state recreation areas, and six state forests, Michigan has the largest state park and state forest system of any state.

Climate

[edit]

Michigan has a continental climate with two distinct regions. The southern and central parts of the Lower Peninsula (south of Saginaw Bay and from the Grand Rapids area southward) have a warmer climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa) with hot summers and cold winters. The northern part of the Lower Peninsula and the entire Upper Peninsula has a more severe climate (Köppen Dfb), with warm, but shorter summers and longer, cold to very cold winters. Some parts of the state average high temperatures below freezing from December through February, and into early March in the far northern parts. During the winter through the middle of February, the state is frequently subjected to heavy lake-effect snow. The state averages from 30 to 40 inches (76 to 102 cm) of precipitation annually; however, some areas in the northern lower peninsula and the upper peninsula average almost 160 inches (4,100 mm) of snowfall per year.[55] Michigan's highest recorded temperature is 112 °F (44 °C) at Mio on July 13, 1936, and the coldest recorded temperature is −51 °F (−46 °C) at Vanderbilt on February 9, 1934.[56]

The state averages 30 days of thunderstorm activity per year. These can be severe, especially in the southern part of the state. The state averages 17 tornadoes per year, which are more common in the state's extreme southern section. Portions of the southern border have been almost as vulnerable historically as states further west and in Tornado Alley. For this reason, many communities in the very southern portions of the state have tornado sirens to warn residents of approaching tornadoes. Farther north, in Central Michigan, Northern Michigan, and the Upper Peninsula, tornadoes are rare.[57][58]

Geology

[edit]The geological formation of the state is greatly varied, with the Michigan Basin being the most major formation. Primary boulders are found over the entire surface of the Upper Peninsula (being principally of primitive origin), while Secondary deposits cover the entire Lower Peninsula. The Upper Peninsula exhibits Lower Silurian sandstones, limestones, copper and iron bearing rocks, corresponding to the Huronian system of Canada. The central portion of the Lower Peninsula contains coal measures and rocks of the Pennsylvanian period. Devonian and sub-Carboniferous deposits are scattered over the entire state.

Michigan rarely experiences earthquakes, and those that it does experience are generally smaller ones that do not cause significant damage. A 4.6-magnitude earthquake struck in August 1947. More recently, a 4.2-magnitude earthquake occurred on Saturday, May 2, 2015, shortly after noon, about five miles south of Galesburg, Michigan (9 miles southeast of Kalamazoo) in central Michigan, about 140 miles west of Detroit, according to the Colorado-based U.S. Geological Survey's National Earthquake Information Center. No major damage or injuries were reported, according to then-Governor Rick Snyder's office.[59]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

State government is decentralized among three tiers—statewide, county and township. Counties are administrative divisions of the state, and townships are administrative divisions of a county. Both of them exercise state government authority, localized to meet the particular needs of their jurisdictions, as provided by state law. There are 83 counties in Michigan.[60]

Cities, state universities, and villages are vested with home rule powers of varying degrees. Home rule cities can generally do anything not prohibited by law. The fifteen state universities have broad power and can do anything within the parameters of their status as educational institutions that is not prohibited by the state constitution. Villages, by contrast, have limited home rule and are not completely autonomous from the county and township in which they are located.

There are two types of township in Michigan: general law township and charter. Charter township status was created by the Legislature in 1947 and grants additional powers and stream-lined administration in order to provide greater protection against annexation by a city. As of April 2001[update], there were 127 charter townships in Michigan. In general, charter townships have many of the same powers as a city but without the same level of obligations. For example, a charter township can have its own fire department, water and sewer department, police department, and so on—just like a city—but it is not required to have those things, whereas cities must provide those services. Charter townships can opt to use county-wide services instead, such as deputies from the county sheriff's office instead of a home-based force of ordinance officers.

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Detroit | Wayne | 639,111 | ||||||

| 2 | Grand Rapids | Kent | 198,917 | ||||||

| 3 | Warren | Macomb | 139,387 | ||||||

| 4 | Sterling Heights | Macomb | 134,346 | ||||||

| 5 | Ann Arbor | Washtenaw | 123,851 | ||||||

| 6 | Lansing | Ingham | 112,644 | ||||||

| 7 | Dearborn | Wayne | 109,976 | ||||||

| 8 | Clinton Charter Township | Macomb | 100,513 | ||||||

| 9 | Canton Charter Township | Wayne | 98,659 | ||||||

| 10 | Livonia | Wayne | 95,535 | ||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 3,757 | — | |

| 1810 | 4,762 | 26.8% | |

| 1820 | 7,452 | 56.5% | |

| 1830 | 28,004 | 275.8% | |

| 1840 | 212,267 | 658.0% | |

| 1850 | 397,654 | 87.3% | |

| 1860 | 749,113 | 88.4% | |

| 1870 | 1,184,059 | 58.1% | |

| 1880 | 1,636,937 | 38.2% | |

| 1890 | 2,093,890 | 27.9% | |

| 1900 | 2,420,982 | 15.6% | |

| 1910 | 2,810,173 | 16.1% | |

| 1920 | 3,668,412 | 30.5% | |

| 1930 | 4,842,325 | 32.0% | |

| 1940 | 5,256,106 | 8.5% | |

| 1950 | 6,371,766 | 21.2% | |

| 1960 | 7,823,194 | 22.8% | |

| 1970 | 8,875,083 | 13.4% | |

| 1980 | 9,262,078 | 4.4% | |

| 1990 | 9,295,297 | 0.4% | |

| 2000 | 9,938,444 | 6.9% | |

| 2010 | 9,883,640 | −0.6% | |

| 2020 | 10,077,331 | 2.0% | |

| 2024 (est.) | 10,140,459 | 0.6% | |

| Sources: 1910–2020[62]

2024[63] | |||

Since 1800 U.S. census, Michigan has experienced relatively positive and stable population growth trends; beginning with a population of 3,757, the 2010 census recorded 9,883,635 residents. At the 2020 United States census, its population was 10,077,331, an increase of 2.03% since 2010's tabulation. According to the United States Census Bureau, it is the third-most populous state in the Midwest and its East North Central subregion, behind Ohio and Illinois.

The center of population of Michigan is in Shiawassee County, in the southeastern corner of the civil township of Bennington, which is northwest of the village of Morrice.[64]

According to the American Immigration Council in 2019, an estimated 6.8% of Michiganders were immigrants, while 3.8% were native-born U.S. citizens with at least one immigrant parent.[65] Numbering approximately 678,255 according to the 2019 survey, the majority of Michigander immigrants came from Mexico (11.5%), India (11.3%), Iraq (7.5%), China (5.3%), and Canada (5.3%); the primary occupations of its immigrants were technology, agriculture, and healthcare. Among its immigrant cohort, there were 108,105 undocumented immigrants, making up 15.9% of the total immigrant population.[65]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 8,206 homeless people in Michigan.[66][67]

Race and ethnicity

[edit]| Self-identified race | 1970[68] | 1990[68] | 2000[69] | 2010[70] | 2020[71] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White American | 88.3% | 83.4% | 80.1% | 78.9% | 73.9% |

| Black or African American | 11.2% | 13.9% | 14.2% | 14.2% | 13.7% |

| Asian American | 0.2% | 1.1% | 1.8% | 2.4% | 3.3% |

| American Indian | 0.2% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.6% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander |

— | — | — | — | — |

| Other race | 0.2% | 0.9% | 1.3% | 1.5% | 2.2% |

| Two or more races | — | — | 1.9% | 2.3% | 6.3% |

Since colonial European and American settlement, the majority of Michigan's population has been predominantly non-Hispanic or non-Latino white; Americans of European descent live throughout every county in the state, and most of Metro Detroit. Large European American groups include those of German, British, Irish, Polish and Belgian ancestry.[72] Scandinavian and Finnish Americans have a notable presence in the Upper Peninsula.[73] Western Michigan is known for its Dutch heritage, especially in Holland and metropolitan Grand Rapids.[74]

Black and African Americans—coming to Detroit and other northern cities in the Great Migration of the early 20th century—have formed a majority of the population in Detroit and other cities including Flint and Benton Harbor. Since the 2021 census estimates—while Detroit was still the largest city in Michigan with a majority black population—it was no longer the largest black-majority city in the U.S., citing crime and higher-paying jobs given to whites.[75][76]

As of 2007[update], about 300,000 people in Southeastern Michigan trace their descent from the Middle East and Asia.[77] Dearborn has a sizeable Arab American community, with many Assyrians, and Lebanese who immigrated for jobs in the auto industry in the 1920s, along with more recent Yemenis and Iraqis.[78] As of 2007[update], almost 8,000 Hmong people lived in the state of Michigan, about double their 1999 presence in the state.[79] Most lived in northeastern Detroit, but they had been increasingly moving to Pontiac and Warren.[80] By 2015, the number of Hmong in the Detroit city limits had significantly declined.[81] Lansing hosts a statewide Hmong New Year Festival.[80] The Hmong community also had a prominent portrayal in the 2008 film Gran Torino, which was set in Detroit.

As of 2015[update], 80% of Michigan's Japanese population lived in the counties of Macomb, Oakland, Washtenaw, and Wayne in the Detroit and Ann Arbor areas.[82] As of April 2013[update], the largest Japanese national population is in Novi, with 2,666 Japanese residents, and the next largest populations are respectively in Ann Arbor, West Bloomfield Township, Farmington Hills, and Battle Creek. The state has 481 Japanese employment facilities providing 35,554 local jobs. 391 of them are in Southeast Michigan, providing 20,816 jobs, and the 90 in other regions in the state provide 14,738 jobs. The Japanese Direct Investment Survey of the Consulate-General of Japan, Detroit stated more than 2,208 additional Japanese residents were employed in the State of Michigan as of 1 October 2012[update], than in 2011.[83] During the 1990s, the Japanese population of Michigan experienced an increase, and many Japanese people with children moved to particular areas for their proximity to Japanese grocery stores and high-performing schools.[82]

Languages

[edit]In 2010, about 91.11% (8,507,947) of Michigan residents age five and older spoke only English at home, while 2.93% (273,981) spoke Spanish, 1.04% (97,559) Arabic, 0.44% (41,189) German, 0.36% (33,648) Chinese (which includes Mandarin), 0.31% (28,891) French, 0.29% (27,019) Polish, and Syriac languages (such as Modern Aramaic and Northeastern Neo-Aramaic) was spoken as a main language by 0.25% (23,420) of the population over the age of five. In total, 8.89% (830,281) of Michigan's population age five and older spoke a mother language other than English.[84] Since 2021, 90.1% of residents aged five and older spoke only English at home, and Spanish was the second-most spoken language with 2.9% of the population speaking it.[85]

Religion

[edit]- Protestantism (43.0%)

- Catholicism (24.0%)

- Jehovah's Witness (1.00%)

- Unaffiliated (28.0%)

- Judaism (1.00%)

- Islam (1.00%)

- Other (2.00%)

Following British and French colonization of the region surrounding Michigan, Christianity became the dominant religion, with Roman Catholicism historically being the largest single Christian group for the state. Until the 19th century, the Roman Catholic Church was the only organized religious group in Michigan, reflecting the territory's French colonial roots. Detroit's St. Anne's parish, established in 1701 by Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, is the second-oldest Roman Catholic parish in the United States.[87] On March 8, 1833, the Holy See formally established a diocese in the Michigan territory, which included all of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakotas east of the Mississippi River. When Michigan became a state in 1837, the boundary of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Detroit was redrawn to coincide with that of the state; the other dioceses were later carved out from the Detroit Diocese but remain part of the Ecclesiastical Province of Detroit.[88] Several Native American religions have been practiced in Michigan.

In 2020, there were 1,492,732 adherents of Roman Catholicism.[89] There's also a significant Independent Catholic presence in Metro Detroit, including the Ecumenical Catholic Church of Christ established by Archbishop Karl Rodig; the see of this church operates in a former Roman Catholic parish church.[90][91][92]

With the introduction of Protestantism to the state, it began to form the largest collective Christian group. In 2010, the Association of Religion Data Archives reported the largest Protestant denomination was the United Methodist Church with 228,521 adherents;[93] followed by the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod with 219,618, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America with 120,598 adherents. The Christian Reformed Church in North America had almost 100,000 members and more than 230 congregations in Michigan.[94] The Reformed Church in America had 76,000 members and 154 congregations in the state.[95] By the 2020 study, non- and inter-denominational Protestant churches formed the largest Protestant group in Michigan, numbering 508,904. The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod grew to become the second-largest single Christian denomination, and United Methodists declined to being the third-largest. The Lutheran Protestant tradition was introduced by German and Scandinavian immigrants. Altogether, Baptists numbered 321,581 between the National Missionary Baptists, National Baptists, American Baptists, Southern Baptists, National Baptists of America, Progressive National Baptists, and Full Gospel Baptists; black Baptists formed the largest constituency.[89] In West Michigan, Dutch immigrants fled from the specter of religious persecution and famine in the Netherlands around 1850 and settled in and around what is now Holland, Michigan, establishing a "colony" on American soil that fervently held onto Calvinist doctrine that established a significant presence of Reformed churches.[96]

In the same 2010 survey, Jewish adherents in the state of Michigan were estimated at 44,382, and Muslims at 120,351.[97] The first Jewish synagogue in the state was Temple Beth El, founded by twelve German Jewish families in Detroit in 1850.[98] Islam was introduced by immigrants from the Near East during the 20th century.[99] Michigan is home to the largest mosque in North America, the Islamic Center of America in Dearborn. Battle Creek, Michigan, is also the birthplace of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which was founded on May 21, 1863.[100][101]

Economy

[edit]| Top publicly traded companies in Michigan according to revenues with state and U.S. rankings | |||||

| State | Corporation | US | |||

| 1 | Ford | 19 | |||

| 2 | General Motors | 21 | |||

| 3 | Dow | 75 | |||

| 4 | Penske Automotive | 147 | |||

| 5 | Lear | 189 | |||

| 6 | Whirlpool | 203 | |||

| 7 | DTE Energy | 212 | |||

| 8 | Stryker | 224 | |||

| 9 | BorgWarner | 262 | |||

| 10 | Kellogg's | 270 | |||

| 11 | Jackson Financial | 282 | |||

| 12 | Ally | 338 | |||

| 13 | Auto-Owners | 362 | |||

| 14 | SpartanNash | 399 | |||

| 15 | UFP Industries | 403 | |||

| 16 | Autoliv | 429 | |||

| 17 | Masco | 436 | |||

| 18 | CMS Energy | 441 | |||

| Further information: List of Michigan companies Source: Fortune[102] | |||||

In 2022, 3,939,076 people in Michigan were employed at 227,870 establishments, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.[3]

The U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis estimated Michigan's Q1 2025 gross state product to be $725.897 billion, ranking 14th out of the 50 states.[13] According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, as of November 2024[update], the state's seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was estimated at 4.8%.[103]

Products and services include automobiles, food products, information technology, aerospace, military equipment, furniture, and mining of copper and iron ore.[quantify] Michigan is the third-largest grower of Christmas trees with 60,520 acres (245 km2) of land dedicated to Christmas tree farming in 2007.[104][105] The beverage Vernors Ginger Ale was invented in Michigan in 1866, sharing the title of oldest soft drink with Hires Root Beer. Faygo was founded in Detroit on November 4, 1907. Two of the top four pizza chains were founded in Michigan and are headquartered there: Domino's Pizza by Tom Monaghan and Little Caesars Pizza by Mike Ilitch. Michigan became the 24th right-to-work state in the U.S. in 2012, however, in 2023 this law was repealed.[106]

Since 2009, GM, Ford and Chrysler have managed a significant reorganization of their benefit funds structure after a volatile stock market which followed the September 11 attacks and early 2000s recession impacted their respective U.S. pension and benefit funds (OPEB).[107] General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler reached agreements with the United Auto Workers Union to transfer the liabilities for their respective health care and benefit funds to a 501(c)(9) Voluntary Employee Beneficiary Association (VEBA). Manufacturing in the state grew 6.6% from 2001 to 2006,[44] but the high speculative price of oil became a factor for the U.S. auto industry during the economic crisis of 2008 impacting industry revenues. In 2009, GM and Chrysler emerged from Chapter 11 restructurings with financing provided in part by the U.S. and Canadian governments.[108][109] GM began its initial public offering (IPO) of stock in 2010.[110] For 2010, the Big Three domestic automakers have reported significant profits indicating the beginning of rebound.[111][112][113][114]

As of 2002[update], Michigan ranked fourth in the U.S. in high-tech employment with 568,000 high-tech workers, which includes 70,000 in the automotive industry.[115] Michigan typically ranks third or fourth in overall research and development (R&D) expenditures in the United States.[116][117] Its research and development, which includes automotive, comprises a higher percentage of the state's overall gross domestic product than for any other U.S. state.[118] The state is an important source of engineering job opportunities. The domestic auto industry accounts directly and indirectly for one of every ten jobs in the U.S.[119]

Michigan was second in the U.S. in 2004 for new corporate facilities and expansions. From 1997 to 2004, Michigan was the only state to top the 10,000 mark for the number of major new developments;[44][120] however, the effects of the late 2000s recession have slowed the state's economy. In 2008, Michigan placed third in a site selection survey among the states for luring new business which measured capital investment and new job creation per one million population.[121] In August 2009, Michigan and Detroit's auto industry received $1.36 B in grants from the U.S. Department of Energy for the manufacture of electric vehicle technologies which is expected to generate 6,800 immediate jobs and employ 40,000 in the state by 2020.[122] From 2007 to 2009, Michigan ranked 3rd in the U.S. for new corporate facilities and expansions.[123][124]

As leading research institutions, the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, and Wayne State University are important partners in the state's economy and its University Research Corridor.[125] Michigan's public universities attract more than $1.5 B in research and development grants each year.[126] The National Superconducting Cyclotron Laboratory is at Michigan State University. Michigan's workforce is well-educated and highly skilled, making it attractive to companies. It has the third highest number of engineering graduates nationally.[127]

Detroit Metropolitan Airport is one of the nation's most recently expanded and modernized airports with six major runways, and large aircraft maintenance facilities capable of servicing and repairing a Boeing 747 and is a major hub for Delta Air Lines. Michigan's schools and colleges rank among the nation's best. The state has maintained its early commitment to public education. The state's infrastructure gives it a competitive edge; Michigan has 38 deep water ports.[128] In 2007, Bank of America announced that it would commit $25 billion to community development in Michigan following its acquisition of LaSalle Bank in Troy.[129]

Michigan was reported to have led the nation in job creation improvement in 2010 according to the Gallup Job Creation Index.[130] A 2015 release of the survey also placed Michigan toward the top of the rankings.[131]

On December 20, 2019, Governor Gretchen Whitmer signed a package of bills into law effectively legalizing online gambling activities in Michigan, which allowed commercial and tribal casinos to apply for internet gaming licenses.[132]

Taxation

[edit]Michigan's personal income tax is a flat rate of 4.25%. In addition, 24 cities impose income taxes; rates are set at 1% for residents and 0.5% for non-residents in all but four cities.[133] Michigan's state sales tax is 6%, though items such as food and medication are exempted. Property taxes are assessed on the local level, but every property owner's local assessment contributes six mills (a rate of $6 per $1000 of property value) to the statutory State Education Tax. Property taxes are appealable to local boards of review and need the approval of the local electorate to exceed millage rates prescribed by state law and local charters. In 2011, the state repealed its business tax and replaced it with a 6% corporate income tax which substantially reduced taxes on business.[134][135] Article IX of the Constitution of the State of Michigan also provides limitations on how much the state can tax.

A 6% use tax is levied on goods purchased outside the state (that are brought in and used in state), at parity with the sales tax.[136] The use tax applies to internet sales/purchases from outside Michigan and is equivalent to the sales tax.[137]

Agriculture

[edit]

A wide variety of commodity crops, fruits, and vegetables are grown in Michigan, making it second only to California among US states in the diversity of its agriculture.[138] The state has 54,800 farms utilizing 10,000,000 acres (40,000 km2) of land which sold $6.49 billion worth of products in 2010.[139] The most valuable agricultural product is milk. Leading crops include corn, soybeans, flowers, wheat, sugar beets, and potatoes. Livestock in the state included 78,000 sheep, a million cattle, a million hogs, and more than three million chickens. Livestock products accounted for 38% of the value of agricultural products while crops accounted for the majority.

Michigan is a leading grower of fruit in the US, including blueberries, tart cherries, apples, grapes, and peaches.[140][141] Michigan produces 70 percent of the country's cherries. Most of these cherries are Montmorency cherries.[142] Plums, pears, and strawberries are also grown in Michigan. These fruits are mainly grown in West Michigan due to the moderating effect of Lake Michigan on the climate. There is also significant fruit production, especially cherries, but also grapes, apples, and other fruits, in northwest Michigan along Lake Michigan. Michigan produces wines, beers and a multitude of processed food products. Kellogg's cereal is based in Battle Creek, Michigan and processes many locally grown foods. Thornapple Valley, Ball Park Franks, Koegel Meat Company, and Hebrew National sausage companies are all based in Michigan.

Michigan is home to very fertile land in the Saginaw Valley and Thumb areas. Products grown there include corn, sugar beets, navy beans, and soybeans. Sugar beet harvesting usually begins the first of October. It takes the sugar factories about five months to process the 3.7 million tons of sugarbeets into 485,000 tons of pure, white sugar.[143] Michigan's largest sugar refiner, Michigan Sugar Company[144] is the largest east of the Mississippi River and the fourth largest in the nation. Michigan sugar brand names are Pioneer Sugar and the newly incorporated Big Chief Sugar. Potatoes are grown in Northern Michigan, and corn is dominant in Central Michigan. Alfalfa, cucumbers, and asparagus are also grown.

Tourism

[edit]

As of 2011, Michigan's tourists spent $17.2 billion per year in the state, supporting 193,000 tourism jobs.[145] Michigan's tourism website ranks among the busiest in the nation.[146] Destinations draw vacationers, hunters, and nature enthusiasts from across the United States and Canada. Michigan is over 50% forest land,[147] much of it quite remote. The forests, lakes and thousands of miles of beaches are top attractions. Event tourism draws large numbers to occasions like the Tulip Time Festival and the National Cherry Festival.

In 2006, the Michigan State Board of Education mandated all public schools in the state hold their first day of school after Labor Day, in accordance with the new post-Labor Day school law. A survey found 70% of all tourism business comes directly from Michigan residents, and the Michigan Hotel, Motel, & Resort Association claimed the shorter summer between school years cut into the annual tourism season.[148] However, a bill introduced in 2023 would cancel this requirement, allowing individual districts to decide when their school year should begin.[149][150]

Tourism in metropolitan Detroit draws visitors to leading attractions, especially The Henry Ford, the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Detroit Zoo, and to sports in Detroit. Other museums include the Detroit Historical Museum, the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, museums in the Cranbrook Educational Community, and the Arab American National Museum. The metro area offers four major casinos, MGM Grand Detroit, Hollywood Casino, Motor City, and Caesars Windsor in Windsor, Ontario, Canada; moreover, Detroit is the largest American city and metropolitan region to offer casino resorts.[151]

Hunting and fishing are significant industries in the state. Charter boats are based in many Great Lakes cities to fish for salmon, trout, walleye, and perch. Michigan ranks first in the nation in licensed hunters (over one million) who contribute $2 billion annually to its economy. More than three-quarters of a million hunters participate in white-tailed deer season alone. Many school districts in rural areas of Michigan cancel school on the opening day of firearm deer season, because of attendance concerns.[citation needed][152]

Michigan's Department of Natural Resources manages the largest dedicated state forest system in the nation. The forest products industry and recreational users contribute $12 billion and 200,000 associated jobs annually to the state's economy. Public hiking and hunting access has also been secured in extensive commercial forests. The state has the highest number of golf courses and registered snowmobiles in the nation.[153]

The state has numerous historical markers, which can themselves become the center of a tour.[154] The Great Lakes Circle Tour is a designated scenic road system connecting all of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River.[155]

With its position in relation to the Great Lakes and the countless ships that have foundered over the many years they have been used as a transport route for people and bulk cargo, Michigan is a world-class scuba diving destination. The Michigan Underwater Preserves are 11 underwater areas where wrecks are protected for the benefit of sport divers.

Culture

[edit]Arts

[edit]Music

[edit]Michigan music is known for three music trends: early punk rock, Motown/soul music and techno music. Michigan musicians include Tally Hall, Bill Haley & His Comets, the Supremes, the Marvelettes, the Temptations, the Four Tops, Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye "The Prince of Soul", Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, Aretha Franklin, Mary Wells, Tommy James and the Shondells, ? and the Mysterians, Al Green, The Spinners, Grand Funk Railroad, the Stooges, the MC5, the Knack, Madonna "The Queen of Pop", Bob Seger, Jack Scott, Ray Parker Jr., Jackie Wilson, Aaliyah, Eminem, Babytron, Kid Rock, Jack White and Meg White (the White Stripes), Big Sean, Alice Cooper, Greta Van Fleet, Mustard Plug, and Del Shannon.[156]

Performance arts

[edit]

Major theaters in Michigan include the Fox Theatre, Music Hall, Gem Theatre, Masonic Temple Theatre, the Detroit Opera House, Fisher Theatre, The Fillmore Detroit, Saint Andrew's Hall, Majestic Theater, and Orchestra Hall.

The Nederlander Organization, the largest controller of Broadway productions in New York City, originated in Detroit.[157]

Sports

[edit]

Michigan's major-league sports teams include: Detroit Tigers baseball team, Detroit Lions football team, Detroit Red Wings ice hockey team, and the Detroit Pistons men's basketball team. All of Michigan's major league teams play in the Metro Detroit area. The state also has a professional second-tier (USL Championship) soccer team in Detroit City FC, which plays its home games at Keyworth Stadium in Hamtramck, Michigan.

The Pistons played at Detroit's Cobo Arena until 1978 and at the Pontiac Silverdome until 1988 when they moved into The Palace of Auburn Hills. In 2017, the team moved to the newly built Little Caesars Arena in downtown Detroit. The Detroit Lions played at Tiger Stadium in Detroit until 1974, then moved to the Pontiac Silverdome where they played for 27 years between 1975 and 2002 before moving to Ford Field in Detroit in 2002. The Detroit Tigers played at Tiger Stadium (formerly known as Navin Field and Briggs Stadium) from 1912 to 1999. In 2000, they moved to Comerica Park. The Red Wings played at Olympia Stadium before moving to Joe Louis Arena in 1979. They later moved to Little Caesars Arena to join the Pistons as tenants in 2017. Professional hockey got its start in 1903 in Houghton, Michigan,[158] when the Portage Lakers were formed.[159]

The Michigan International Speedway is the site of NASCAR races and Detroit was formerly the site of a Formula One World Championship Grand Prix race. From 1959 to 1961, Detroit Dragway hosted the NHRA's U.S. Nationals.[160] Michigan is home to one of the major canoeing marathons: the 120-mile (190 km) Au Sable River Canoe Marathon. The Port Huron to Mackinac Boat Race is also a favorite.

Twenty-time Grand Slam champion Serena Williams was born in Saginaw. The 2011 World Champion for Women's Artistic Gymnastics, Jordyn Wieber is from DeWitt. Wieber was also a member of the gold medal team at the London Olympics in 2012.

Collegiate sports in Michigan are popular in addition to professional sports. The state's two largest athletic programs are the Michigan Wolverines and Michigan State Spartans. They compete in the NCAA Big Ten Conference for most sports. The Michigan High School Athletic Association features around 300,000 participants.

Education

[edit]Michigan's education system serves nearly 1.4 million K-12 students in public schools as of the 2024-25 school year.[161] In 2008-09, more than 124,000 students attend private schools and an uncounted number are homeschooled under certain legal requirements.[162][163] The public school system had a $14.5 billion budget in 2008–09.[164] From 2009 to 2019, over 200 private schools in Michigan closed, partly due to competition from charter schools.[165] In 2022, U.S. News & World Report rated three Michigan high schools among the nation's 100 best: City High Middle School (18th), the International Academy of Macomb (21st), and the International Academy (52nd). Washtenaw International High School ranked 107th.[166]

The University of Michigan is Michigan's oldest higher educational institution and among the oldest research universities in the nation. It was founded in 1817, 20 years before Michigan Territory achieved statehood.[167][168] Kalamazoo College is the state's oldest private liberal arts college, founded in 1833 by a group of Baptist ministers as the Michigan and Huron Institute. From 1840 to 1850, the college operated as the Kalamazoo Branch of the University of Michigan. Methodist settlers in Spring Arbor Township founded Albion College in 1835. It is the state's second-oldest private liberal arts college.

Michigan Technological University is the first post-secondary institution in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, founded in 1885 as the Michigan Mining School. Eastern Michigan University was founded in 1849 as the Michigan State Normal School for the training of teachers. It was the nation's fourth-oldest normal school and the first U.S. normal school outside New England. In 1899, the Michigan State Normal School became the nation's first normal school to offer a four-year curriculum. Michigan State University was founded in 1855 as the nation's first agricultural college.

The Carnegie Foundation classifies eight of the state's institutions (Michigan State University, Michigan Technological University, Eastern Michigan University, Wayne State University, Central Michigan University, Western Michigan University, Oakland University, University of Michigan) as research universities.[169]

The state of Michigan has six MD-granting medical schools: Central Michigan University College of Medicine, University of Michigan Medical School, Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, Oakland University William Beaumont School of Medicine, Wayne State University School of Medicine, and Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine. Additionally, Michigan is home to five American Bar Association accredited law schools: Michigan State University College of Law, Cooley Law School, University of Detroit Mercy School of Law, University of Michigan Law School, and Wayne State University Law School.

Infrastructure

[edit]Energy

[edit]

In 2020, Michigan consumed 113,740- gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electrical energy and produced 116,700 (GWh) of electrical energy.[170]

Coal power is Michigan's leading source of electricity, producing roughly half its supply or 53,100 GWh of electrical energy (12.6 GW total capacity) in 2020.[170] Although Michigan has no active coal mines, coal is easily moved from other states by train and across the Great Lakes by lake freighters. The lower price of natural gas is leading to the closure of most coal plants, with Consumer Energy planning to close all of its remaining coal plants by 2025;[171] DTE plans to retire 2100MW of coal power by 2023.[172] The coal-fired Monroe Power Plant in Monroe, on the western shore of Lake Erie, is the nation's 11th-largest electric plant, with a net capacity of 3,400 MW.

Nuclear power is also a significant source of electrical power in Michigan, producing roughly one-quarter of the state's supply or 28,000-gigawatt-hours (GWh) of electrical energy (4.3 GW total capacity) in 2020.[170] The three active nuclear power plants supply Michigan with about 26% of its electricity. Donald C. Cook Nuclear Plant, just north of Bridgman, is the state's largest nuclear power plant, with a net capacity of 2,213 MW. The Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station is the second-largest, with a net capacity of 1,150 MW. It is also one of the two nuclear power plants in the Detroit metropolitan area (within a 50-mile radius of Detroit's city center), about halfway between Detroit and Toledo, Ohio, the other being the Davis–Besse Nuclear Power Station, in Ottawa County, Ohio. The Palisades Nuclear Power Plant, south of South Haven, closed in May 2022.[173] The Big Rock Point Nuclear Power Plant, Michigan's first nuclear power plant and the nation's fifth, was decommissioned in 1997.

Utility companies were required to generate at least 10% of their energy from renewable sources by 2015, under Public Act 295 of 2008. In 2016, the legislature set another mandate to reach at least 12.5% renewable energy by 2019 and 15% by end of year 2021, which all utilities subject to the law successfully met. By the end of 2022, Michigan had at least 6 GW of renewable generating capacity, and was projected to have at least 8 GW by the end of 2026. Wind energy accounted for 59% of all Michigan energy credits in 2021.[174][175]

Transportation

[edit]International crossings

[edit]

Michigan has nine international road crossings with Ontario, Canada:

- Ambassador Bridge, North America's busiest international border, crossing the Detroit River

- Blue Water Bridge, a twin-span bridge (Port Huron, Michigan, and Point Edward, Ontario, but the larger city of Sarnia is usually referred to on the Canadian side)

- Blue Water Ferry (Marine City, Michigan, and Sombra, Ontario)

- Canadian Pacific Railway tunnel

- Detroit–Windsor Truck Ferry (Detroit and Windsor)

- Detroit–Windsor Tunnel

- International Bridge (Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan, and Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario)

- St. Clair River Railway Tunnel (Port Huron and Sarnia)

- Walpole Island Ferry (Algonac, Michigan, and Walpole Island First Nation, Ontario)

The Gordie Howe International Bridge, a second international bridge between Detroit and Windsor, is under construction. It is expected to be completed in early 2026.[176][177][178][179]

Railroads

[edit]Michigan is served by four Class I railroads: the Canadian National Railway, the Canadian Pacific Railway, CSX Transportation, and the Norfolk Southern Railway. These are augmented by several dozen short line railroads. The vast majority of rail service in Michigan is devoted to freight, with Amtrak and various scenic railroads the exceptions.[180]

Three Amtrak passenger rail routes serve the state. The Pere Marquette from Chicago to Grand Rapids, the Blue Water from Chicago to Port Huron, and the Wolverine from Chicago to Pontiac. There are plans for commuter rail for Detroit and its suburbs (see SEMCOG Commuter Rail).[181][182][183]

Roadways

[edit]

- Interstate 75 (I-75) is the main thoroughfare between Detroit, Flint, and Saginaw extending north to Sault Ste. Marie and providing access to Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. The freeway crosses the Mackinac Bridge between the Lower and Upper Peninsulas. Auxiliary highways include I-275 and I-375 in Detroit; I-475 in Flint; and I-675 in Saginaw.

- I-69 enters the state near the Michigan–Ohio–Indiana border, and it extends to Port Huron and provides access to the Blue Water Bridge crossing into Sarnia, Ontario.

- I-94 enters the western end of the state at the Indiana border, and it travels east to Detroit and then northeast to Port Huron and ties in with I-69. I-194 branches off from this freeway in Battle Creek. I-94 is the main artery between Chicago and Detroit.

- I-96 runs east–west between Detroit and Muskegon. I-496 loops through Lansing. I-196 branches off from this freeway at Grand Rapids and connects to I-94 near Benton Harbor. I-696 branches off from this freeway at Novi and connects to I-94 near St. Clair Shores.

- U.S. Highway 2 (US 2) enters Michigan at the city of Ironwood and travels east to the town of Crystal Falls, where it turns south and briefly re-enters Wisconsin northwest of Florence. It re-enters Michigan north of Iron Mountain and continues through the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to the cities of Escanaba, Manistique, and St. Ignace. Along the way, it cuts through the Ottawa and Hiawatha national forests and follows the northern shore of Lake Michigan. Its eastern terminus lies at exit 344 on I-75, just north of the Mackinac Bridge.

- US 23 enters Michigan at the Ohio state line in the suburban spillover of Toledo, Ohio, as a freeway and leads northward to Ann Arbor before merging with I-75 just south of Flint. Concurrent with I-75 through Flint, Saginaw, and Bay City, it splits from I-75 at Standish as an intermittently four-lane/two-lane surface road closely following the western shore of Lake Huron generally northward through Alpena before turning west to northwest toward Mackinaw City and I-75 again, where it terminates.

- US 31 enters Michigan as Interstate-quality freeway at the Indiana state line just northwest of South Bend, Indiana, heads north to I-196 near Benton Harbor, and follows the eastern shore of Lake Michigan to Mackinaw City, where it has its northern terminus.

- US 127 enters Michigan from Ohio south of Hudson as a two-lane, undivided highway and closely follows the Michigan meridian, the principal north–south line used to survey Michigan in the early 19th century. It passes north through Jackson and Lansing before terminating south of Grayling at I-75, and is a four-lane freeway for the majority of its course.

- US 131 has its southern terminus at the Indiana Toll Road roughly one mile south of the Indiana state line as a two-lane surface road. It passes through Kalamazoo and Grand Rapids as a freeway of Interstate standard and continues as such to Manton, where it reverts to two-lane surface road to its northern terminus at US 31 in Petoskey.

Intercity bus services

[edit]Airports

[edit]

Detroit Metropolitan Airport in the western suburb of Romulus, was in 2010 the 16th busiest airfield in North America measured by passenger traffic.[184] The Gerald R. Ford International Airport in Grand Rapids is the next busiest airport in the state, served by eight airlines to 23 destinations. Flint Bishop International Airport is the third largest airport in the state, served by four airlines to several primary hubs. Other frequently trafficked airports include Cherry Capital Airport, in Traverse City; Kalamazoo/Battle Creek International Airport, serving the Kalamazoo and Battle Creek region; Capital Region International Airport, located outside of Lansing; and MBS International Airport serving the Midland, Bay City and Saginaw tri-city region. Additionally, smaller regional and local airports are located throughout the state including on several islands.

Government

[edit]State government

[edit]

Michigan is governed as a republic, with three branches of government: the executive branch consisting of the Governor of Michigan and the other independently elected constitutional officers; the legislative branch consisting of the House of Representatives and Senate; and the judicial branch. The Michigan Constitution allows for the direct participation of the electorate by statutory initiative and referendum, recall, and constitutional initiative and referral (Article II, § 9,[185] defined as "the power to propose laws and to enact and reject laws, called the initiative, and the power to approve or reject laws enacted by the legislature, called the referendum. The power of initiative extends only to laws which the legislature may enact under this constitution"). Lansing is the state capital and is home to all three branches of state government.

The governor and the other state constitutional officers serve four-year terms and may be re-elected only once. The current governor is Gretchen Whitmer. Michigan has two official Governor's Residences; one is in Lansing, and the other is on Mackinac Island. The other constitutionally elected executive officers are the lieutenant governor, who is elected on a joint ticket with the governor; the secretary of state; and the attorney general. The lieutenant governor presides over the Senate (voting only in case of a tie) and is also a member of the cabinet. The secretary of state is the chief elections officer and is charged with running many licensure programs including motor vehicles, all of which are done through the branch offices of the secretary of state.

The Michigan Legislature consists of a 38-member Senate and 110-member House of Representatives. Members of both houses of the legislature are elected through first past the post elections by single-member electoral districts of near-equal population that often have boundaries which coincide with county and municipal lines. Senators serve four-year terms concurrent to those of the governor, while representatives serve two-year terms. The Michigan State Capitol was dedicated in 1879 and has hosted the executive and legislative branches of the state ever since.

The Michigan judiciary consists of two courts with primary jurisdiction (the Circuit Courts and the District Courts), one intermediate level appellate court (the Michigan Court of Appeals), and the Michigan Supreme Court. There are several administrative courts and specialized courts. District courts are trial courts of limited jurisdiction, handling most traffic violations, small claims, misdemeanors, and civil suits where the amount contended is below $25,000. District courts are often responsible for handling the preliminary examination and for setting bail in felony cases. District court judges are elected to terms of six years. In a few locations, municipal courts have been retained to the exclusion of the establishment of district courts. There are 57 circuit courts in the State of Michigan, which have original jurisdiction over all civil suits where the amount contended in the case exceeds $25,000 and all criminal cases involving felonies. Circuit courts are also the only trial courts in the State of Michigan which possess the power to issue equitable remedies. Circuit courts have appellate jurisdiction from district and municipal courts, as well as from decisions and decrees of state agencies. Most counties have their own circuit court, but sparsely populated counties often share them. Circuit court judges are elected to terms of six years. State appellate court judges are elected to terms of six years, but vacancies are filled by an appointment by the governor. There are four divisions of the Court of Appeals in Detroit, Grand Rapids, Lansing, and Marquette. Cases are heard by the Court of Appeals by panels of three judges, who examine the application of the law and not the facts of the case unless there has been grievous error pertaining to questions of fact. The Michigan Supreme Court consists of seven members who are elected on non-partisan ballots for staggered eight-year terms. The Supreme Court has original jurisdiction only in narrow circumstances but holds appellate jurisdiction over the entire state judicial system.

Law

[edit]

Michigan has had four constitutions, the first of which was ratified on October 5 and 6, 1835.[186] There were also constitutions from 1850 and 1908, in addition to the current constitution from 1963. The current document has a preamble, 11 articles, and one section consisting of a schedule and temporary provisions. The current constitution also includes a provision beginning in the general election held in 1978, and every 16 years thereafter, the question of a general revision of the constitution shall be submitted to the electors of the state, next scheduled to be considered November 2026.[187][188] Michigan, like every U.S. state except Louisiana, has a common law legal system.

Politics

[edit]

Having been a Democratic-leaning state at the presidential level since the 1990s, Michigan has evolved into a swing state after Donald Trump won the state in 2016. He then won it again in 2024, after losing it by a slim 2.8% to Democrat Joe Biden in 2020. Governors since the 1970s have alternated between the Democrats and Republicans, and statewide offices including attorney general, secretary of state, and senator have been held by members of both parties in varying proportion. Additionally, from 1994 until 2022, the governor-elect had always come from the party opposite the presidency. Following the 2024 elections, control of Michigan Legislature is split, with the Democratic Party having a slim majority of two seats in the Senate while the Republican Party holds a 58-seat majority in the House. The state's congressional delegation is commonly split, with one party or the other typically holding a narrow majority; as of 2025 Republicans have a 7–6 majority.

Michigan was the home of Gerald Ford, the 38th president of the United States. Born in Nebraska, he moved as an infant to Grand Rapids.[189][190] The Gerald R. Ford Museum is in Grand Rapids, and the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library is on the campus of his alma mater, the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

In a 2020 study, Michigan was ranked as the 13th easiest state for citizens to vote in.[191] Amendments to the constitution in 2020 and 2022 also provide for voting by mail, audits of statewide election results, and to vote free of harassment, threats, and intimidation.[192] The Cato Institute ranks Michigan 7th in its overall ranking for personal and economic freedom in the United States in the 2021 and 2023 editions of its Freedom in the 50 States index.[193] In 2022, Michigan voters passed an amendment recognizing abortion and contraceptive rights within the state's constitution.[194]

State symbols and nicknames

[edit]

Michigan is traditionally known as "The Wolverine State", and the University of Michigan uses the wolverine as its mascot. The association is well and long established: for example, many Detroiters volunteered to fight during the American Civil War and George Armstrong Custer, who led the Michigan Brigade, called them the "Wolverines". The origins of this association are obscure; it may derive from a busy trade in wolverine furs in Sault Ste. Marie in the 18th century or may recall a disparagement intended to compare early settlers in Michigan with the vicious mammal. Wolverines are, however, extremely rare in Michigan. A sighting in February 2004 near Ubly was the first confirmed sighting in Michigan in 200 years.[195] Another wolverine was found dead in 2010.[196]

- State nicknames: Wolverine State, Great Lakes State, Mitten State, Water-Winter Wonderland

- State motto: Si quaeris peninsulam amoenam circumspice (Latin: "If you seek a pleasant peninsula, look about you") adopted in 1835 on the coat-of-arms, but never as an official motto. This is a paraphrase of the epitaph of British architect Sir Christopher Wren about his masterpiece, St. Paul's Cathedral.[197][198]

- State song: "My Michigan" (official since 1937, but disputed amongst residents),[199] "Michigan, My Michigan" (unofficial state song, since the civil war)

- State bird: American robin (since 1931)

- State animal: wolverine (traditional)

- State game animal: white-tailed deer (since 1997)

- State fish: brook trout (since 1965)

- State reptile: painted turtle (since 1995)

- State fossil: mastodon (since 2000)

- State flower: apple blossom (adopted in 1897, official in 1997)

- State wildflower: dwarf lake iris (since 1998) a federally listed threatened species

- State tree: white pine (since 1955)

- State stone: Petoskey stone (since 1965). It is composed of fossilized coral (Hexagonaria pericarnata) from long ago when the middle of the continent was covered with a shallow sea.

- State gem: Isle Royale greenstone (since 1973). Also called chlorastrolite (literally "green star stone"), the mineral is found on Isle Royale and the Keweenaw peninsula.

- State quarter: US coin issued in 2004 with the Michigan motto "Great Lakes State".

- State soil: Kalkaska sand (since 1990), ranges in color from black to yellowish brown, covers nearly 1,000,000-acre (4,000 km2) in 29 counties.

Sister regions

[edit] Shiga Prefecture, Japan[200]

Shiga Prefecture, Japan[200] Sichuan Province, People's Republic of China[201]

Sichuan Province, People's Republic of China[201]

See also

[edit]- Index of Michigan-related articles

- Outline of Michigan: organized list of topics about Michigan

- USS Michigan, 3 ships

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988

- ^ i.e., including water that is part of state territory. Georgia is the largest state by land area alone east of the Mississippi and Michigan the second-largest.

- ^ The first form is the way it is spelled in Ojibwe native syllabics.