Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hadramautic language

View on Wikipedia| Hadhramautic | |

|---|---|

| Hadrami | |

| Native to | Yemen, Oman, Saudi Arabia |

| Era | 800 BC – 600 AD |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

| Ancient South Arabian | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | xhd |

xhd | |

| Glottolog | hadr1235 |

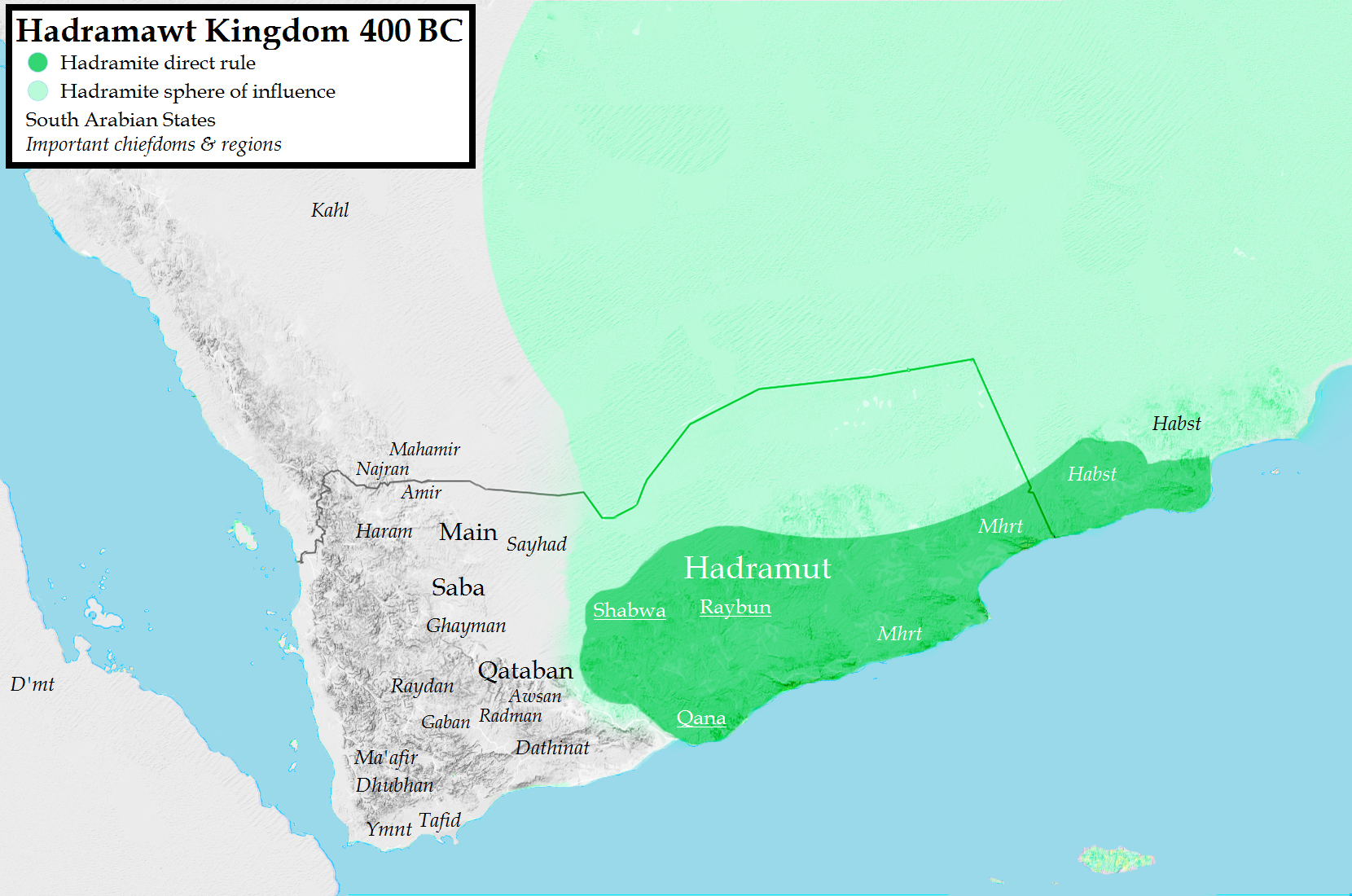

Kingdom of Hadramawt in 400 BC | |

Ḥaḍramautic or Ḥaḍramic[1] was the easternmost of the four known languages of the Old South Arabian subgroup of the Semitic languages. It was used in the Kingdom of Hadhramaut and also the area round the Hadhramite capital of Shabwa, in what is now Yemen. The Hadramites also controlled the trade in frankincense through their important trading post of Sumhuram (Hadramautic s1mhrm), now Khor Rori in the Dhofar Governorate, Oman.

Script and phonology

[edit]

Almost the entire body of evidence for the ancient Ḥaḍramautic language comes from inscriptions written in the monumental Ancient South Arabian script, consisting of 29 letters, and deriving from the Proto-Sinaitic script. The sounds of the language were essentially the same as those of Sabaic.

Noteworthy characteristics of Ḥaḍramautic include its tendency, especially in inscriptions from Wadi Ḥaḍhramaut, to represent Old South Arabian ṯ as s3: thus we find s2ls3 ("three"; cf. Sabaean s2lṯ.)[2] There are also instances where ṯ is written for an older form s3; e.g. Ḥaḍramautic mṯnad ("inscription"), which is msnd in the rest of Old South Arabian.[2]

History

[edit]Potsherds with Ancient South Arabian letters on them, found in Raybūn, the old Ḥaḍramitic capital, have been radiocarbon dated to the 12th century BC.[3] The language was certainly in use from 800 BC but in the fourth century AD, the Kingdom of Hadhramaut was conquered by the Ḥimyarites, who used Sabaic as an official language, and after then there are no more records in Ḥaḍramautic.

During the course of the language’s history there appeared particular phonetic changes, such as the change from ˤ to ˀ, from ẓ to ṣ, from ṯ to s3. As in other Semitic languages n can be assimilated to a following consonant, compare ʾnfs1 "souls" > ʾfs1

In Ḥaḍramautic the third person pronouns begin with s1. It has feminine forms ending in ṯ and s3.

References

[edit]- ^ Bin Mukhashin, Khaled Awadh; Shuib, Munir (December 1, 2016). "The Pronominal System of the Soqotri Dialects: A structural and functional Study". Macrolinguistics. 4 (5): 39. doi:10.26478/ja2016.4.5.3.

- ^ a b Kogan & Korotayev 1997, p. 223.

- ^ Kogan & Korotayev 1997, p. 220.

Bibliography

[edit]- Kogan, Leonid; Korotayev, Andrey (1997). "Sayhadic Languages (Epigraphic South Arabian)". Semitic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 157–183.

Hadramautic language

View on GrokipediaClassification and overview

Linguistic affiliation

Hadramautic is classified as a South Semitic language within the Semitic branch of the Afroasiatic language family.[4] This placement reflects its historical ties to the ancient languages of the Arabian Peninsula, where Semitic languages diverged from Proto-Afroasiatic through shared phonological and morphological features traceable to Proto-Semitic roots, such as triconsonantal verbal stems. Within the South Semitic subgroup, Hadramautic is recognized as one of the four primary Old South Arabian (OSA) languages, alongside Sabaic, Minaic, and Qatabanic. It is distinguished as the easternmost of these languages, primarily attested in regions corresponding to ancient Hadramawt.[5] Etymological and comparative analyses highlight its close relations to the other OSA languages through shared innovations, including the suffixed definite article -ʔ, which marks nouns for definiteness and differs from the prefixed articles in Northwest Semitic languages like Arabic and Hebrew. These features underscore a common OSA development from earlier Semitic stages, with lexical and morphological parallels to Proto-Semitic forms evident in cognates for basic vocabulary and grammatical markers.[1] The language is documented under the ISO 639-3 code xhd and the Glottolog identifier hadr1235, facilitating its study within comparative Semitic linguistics.[6][5]Geographic and temporal scope

The Hadramautic language was primarily spoken and attested in the Kingdom of Hadramaut, centered in the ancient capital of Shabwa in modern-day Yemen, corresponding to the core territory of Hadramawt, though the kingdom controlled key trade routes extending into adjacent regions of present-day Oman and Saudi Arabia.[1] Hadramautic is attested epigraphically from the 7th century BCE until the 3rd century CE, with some evidence extending to the 6th century CE, marking its temporal range within the Old South Arabian linguistic tradition.[1] The language remained closely tied to the Hadramaut polity from the early 1st millennium BCE through its period of independence, until the Himyarite conquest in the late 3rd to early 4th century CE, after which Sabaic supplanted Hadramautic as the dominant administrative language in the region.[7] Following this political shift, Hadramautic gradually declined, ceasing to function as a spoken language by the 6th century CE while persisting in isolated epigraphic inscriptions for a brief additional period.[1]Writing system

Ancient South Arabian script

The Ancient South Arabian script, known as musnad in its monumental form, served as the primary writing system for the Hadramautic language, one of the Old South Arabian dialects spoken in the region of Hadramaut from approximately the 8th century BCE to the 6th century CE.[1] This script originated in the southern Arabian Peninsula, deriving from earlier Northwest Semitic alphabetic traditions, including influences from the Proto-Sinaitic script of the late 2nd millennium BCE, through possible Levantine intermediaries that introduced consonantal writing to the region by the early 1st millennium BCE.[8] Over time, it evolved into a distinct monumental style characterized by angular, lapidary letter forms suited for carving into hard surfaces, while a shared cursive variant (zabūr) is attested in ASA more broadly, primarily on perishable materials like wood, it is rarer in the Hadramautic corpus, which predominantly features monumental forms.[1] As a right-to-left abjad, the script consisted of 29 consonantal letters, omitting dedicated symbols for vowels and relying instead on contextual interpretation or occasional use of weak consonants (w and y) as mater lectionis to indicate long vowels in certain positions.[8][1] The letter inventory preserved a full Proto-Semitic consonantal system, including distinctions for emphatic sounds such as the pharyngealized stops ṭ, ṣ, and ḍ, as well as the sibilant series often reconstructed as s¹ (represented by ś, a lateral or affricated fricative), s² (s, a simple sibilant), and s³ (š, a sibilant akin to sh).[1] These emphatic consonants were denoted by dedicated glyphs with robust, blocky shapes— for instance, the letter for ṣ (emphatic s) featured a triangular or arrowhead form that remained stable across centuries, while ś evolved from more curved early variants to straighter lines in later Hadramautic examples.[8] Hadramautic texts in this script appear predominantly in monumental inscriptions on durable media, such as stone stelae, altars, and rock faces commemorating royal dedications, legal decrees, or funerary rites in key sites like Shabwa and Raybun.[1] Minor applications included incised or painted marks on pottery shards and occasional metal objects, though these are rarer and typically shorter, reflecting the script's adaptation primarily for formal, public epigraphy rather than everyday notation.[9] The uniformity of the script across Old South Arabian languages, including Hadramautic, underscores its role as a shared cultural technology, with letter forms showing gradual refinement in stroke thickness and proportion from the 8th century BCE onward, but without dialect-specific orthographic innovations in form.[1]Orthographic conventions

The Hadramautic language utilized the Ancient South Arabian (ASA) script, a 29-consonant abjad shared among Old South Arabian languages, but adapted it with distinctive conventions that reflect its phonological and lexical particularities.[10] A key orthographic practice in Hadramautic involves pleonastic insertions of consonants, particularly w and y, to approximate vowel qualities or clarify word boundaries in the absence of dedicated vowel markers. These redundant letters, such as inserting w after a final consonant to suggest a following u-vowel or y for an i-vowel, appear sporadically in inscriptions and serve to disambiguate readings without altering the core consonantal skeleton. For instance, in verbal forms or nominal endings, such insertions prevent conflation of homographic roots, though their use varies by region and period, being more frequent in later Hadramautic texts from the Wadi Ḥaḍramaut. Additionally, long vowels are occasionally indicated by w and y as matres lectionis, particularly at word ends, though this practice is inconsistent across the corpus.[11][1] Hadramautic orthography also features innovative representations for certain sibilants, with a merger of the sibilant /ś/ with the interdental /ṯ/ from the earliest attestations, represented variably by the letters for ṯ (older) or ś (later), as seen in the feminine numeral "three" as šlṯt or šlśt, in contrast to the consistent ṯlṯt in Sabaic. This merger reflects Hadramautic's peripheral innovations within the ASA sibilant system, aiding philologists in identifying dialectal boundaries through comparative epigraphy.[1] In dedicatory and commemorative inscriptions, Hadramautic employs standardized formulas with language-specific prepositional constructions, diverging from central OSA varieties. A prominent example is the term mṯnad for "inscription" or "dedicatory monument," used in phrases marking offerings to deities like Sin or ʿAthtar, in contrast to the more widespread msnd in Sabaic and Minaic. These formulas typically begin with prepositions like l- ("for") or b- ("in"), followed by the beneficiary's name and purpose, underscoring Hadramautic's ritual lexicon while adhering to the broader ASA monumental style. The overall absence of vowel notation in Hadramautic, like other ASA languages, engenders interpretive challenges, such as distinguishing between potential long/short vowels or case endings, which scholars resolve via etymological comparisons with Arabic, Ethiosemitic, and Northwest Semitic cognates.[10]Phonology

Consonant inventory

The Hadramautic language features a consonantal system based on the 29-letter Ancient South Arabian (ASA) script, preserving much of the Proto-Semitic structure but with mergers reducing the number of distinct phonemes, which distinguishes it as one of the more conservative South Semitic varieties.[12] This system includes a full set of emphatics such as ṭ, ṣ, ḍ, and q, which maintain pharyngealized or uvular qualities akin to their Proto-Semitic prototypes, and a triplet of sibilants s¹, s², and s³, traditionally reconstructed as fricative, lateral fricative, and postalveolar fricative realizations respectively.[12] These consonants are attested across the corpus of Hadramautic inscriptions, where orthographic conventions denote them without vowel indications, emphasizing their role in root-based morphology.[13] Hadramautic shows specific innovations including the merger of the sibilant *ś with the interdental *ṯ (e.g., šlṯt "three (f.)" vs. šlśt in Sabaic), *ˤ to ʔ, *ẓ to ṣ, and possibly *z to ḏ, reducing contrasts in sibilants, emphatics, and resonants.[12] Relative to Proto-Semitic, these changes simplify the inventory while retaining key distinctions. Additionally, Proto-Semitic *ṯ regularly becomes s³ in Hadramautic, evident in numerals (e.g., ṯlṯ "three" > s³lṯ) and third-person pronouns, marking a dialectal divergence from Sabaic and other ASA languages.[12] In contrast, the gutturals ʾ, h, ḥ, ʿ, and ġ are largely preserved without loss or merger, supporting etymological connections to broader Semitic lexicon, while the liquids l, r and nasals m, n remain stable, facilitating clear morphological patterns.[13] Assimilation processes further characterize Hadramautic consonants, particularly the elision of n in preconsonantal position within certain clusters, as in the form ʾnfs¹ developing into ʾfs¹ for "soul," where the nasal assimilates completely to the following sibilant.[12] Such patterns, observed in dedicatory and funerary inscriptions, highlight phonetic adaptations that streamline pronunciation without disrupting semantic clarity.[13]| Place of Articulation | Bilabial | Dental/Alveolar | Post-Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops (voiceless) | t | k | q | ʔ | ||||

| Stops (voiced) | b | d | g | |||||

| Stops (emphatic) | ṭ, ḍ | |||||||

| Fricatives (voiceless) | f | θ, s¹, s², s³ | š | ḥ | h | |||

| Fricatives (voiced) | ð | ġ | ʿ | |||||

| Fricatives (emphatic) | ṣ | |||||||

| Nasals | m | n | ||||||

| Laterals | l | |||||||

| Trills | r | |||||||

| Semivowels | w | y |