Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

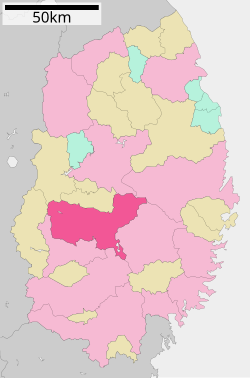

Hanamaki, Iwate

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

Hanamaki (花巻市, Hanamaki-shi) is a city in Iwate Prefecture, Japan. As of 31 March 2020[update], the city had an estimated population of 94,691, and a population density of 100 persons per km2, in 37,773 households.[1] The total area of the city is 908.39 square kilometres (350.73 sq mi).[2] Hanamaki is famous as the birthplace of the novelist and poet Kenji Miyazawa and Iwate Prefecture's local specialty, Wanko soba, as well as its hot spring resorts.

Geography

[edit]Hanamaki is located in central Iwate Prefecture, in the Kitakami River valley at the conflux of three rivers with the Kitakami River; the Sarugaishi-gawa from the east and the Se-gawa and Toyosawa-gawa from the west. In the west the city rises to the foothills of the Ōu Mountains with the highest peak being Mt. Matsukura at 968 metres (3,176 ft). To the east the city rises to the highest peak in the Kitakami Range, Mount Hayachine at 1,917 metres (6,289 ft). The largest reservoir is Lake Tase on the Sarugaishi River. Lake Hayachine on the Hienuki River is quite spectacular with steep mountains rising above it. Lake Toyosawa is in the western part of the city on the Toyosawa River. Parts of the city are within the borders of the Hayachine Quasi-National Park. A chain of 12 hot springs that lie along the edge of the Ōu Mountains form the Hanamaki Onsenkyo Village.

Neighboring municipalities

[edit]Iwate Prefecture

Climate

[edit]Hanamaki has a humid climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) characterized by mild summers and cold winters. The average annual temperature in Hanamaki is 10.4 °C (50.7 °F). The average annual rainfall is 1,324 millimetres (52.1 in) with September as the wettest month. The temperatures are highest on average in August, at around 24.0 °C (75.2 °F), and lowest in January, at around −2.3 °C (27.9 °F).[3]

| Climate data for Hanamaki, Iwate (2003−2020 normals, extremes 2003−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 9.1 (48.4) |

13.6 (56.5) |

22.1 (71.8) |

29.3 (84.7) |

33.3 (91.9) |

34.0 (93.2) |

36.6 (97.9) |

36.3 (97.3) |

35.8 (96.4) |

28.9 (84.0) |

21.9 (71.4) |

17.3 (63.1) |

36.6 (97.9) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 2.4 (36.3) |

3.7 (38.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

15.0 (59.0) |

21.4 (70.5) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

29.3 (84.7) |

25.2 (77.4) |

18.7 (65.7) |

11.8 (53.2) |

4.9 (40.8) |

16.1 (61.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −1.8 (28.8) |

−0.9 (30.4) |

3.0 (37.4) |

8.7 (47.7) |

15.1 (59.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

24.0 (75.2) |

19.7 (67.5) |

12.9 (55.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

0.8 (33.4) |

10.8 (51.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −6.4 (20.5) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−2.1 (28.2) |

2.7 (36.9) |

9.3 (48.7) |

14.5 (58.1) |

18.8 (65.8) |

19.9 (67.8) |

15.4 (59.7) |

7.7 (45.9) |

1.6 (34.9) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

6.1 (42.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −17.5 (0.5) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

−11.8 (10.8) |

−6.9 (19.6) |

−0.6 (30.9) |

5.1 (41.2) |

10.9 (51.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

4.3 (39.7) |

−1.6 (29.1) |

−10.2 (13.6) |

−14.8 (5.4) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 51.7 (2.04) |

49.4 (1.94) |

80.8 (3.18) |

97.6 (3.84) |

98.8 (3.89) |

120.0 (4.72) |

205.0 (8.07) |

156.0 (6.14) |

156.8 (6.17) |

125.3 (4.93) |

84.0 (3.31) |

85.0 (3.35) |

1,310.4 (51.59) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 10.7 | 10.1 | 11.4 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 9.0 | 13.1 | 11.4 | 10.3 | 10.2 | 12.7 | 13.9 | 133.2 |

| Source: JMA[4][5] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]Per Japanese census data,[6] the population of Hanamaki peaked at around the year 2000 and has declined since.

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1920 | 69,110 | — |

| 1930 | 79,108 | +14.5% |

| 1940 | 83,401 | +5.4% |

| 1950 | 102,933 | +23.4% |

| 1960 | 105,687 | +2.7% |

| 1970 | 101,858 | −3.6% |

| 1980 | 105,678 | +3.8% |

| 1990 | 106,727 | +1.0% |

| 2000 | 107,175 | +0.4% |

| 2010 | 101,451 | −5.3% |

| 2020 | 93,193 | −8.1% |

History

[edit]The area of present-day Hanamaki was part of ancient Mutsu Province, and has been settled since at least the Jōmon period. During the Sengoku period, the area was dominated by various samurai clans before coming under the control of the Nambu clan during the Edo period, who ruled Morioka Domain under the Tokugawa shogunate. The town developed as a post station on the Ōshū Kaidō highway during the Edo period.

In the Meiji period, with the establishment of the modern municipalities system on April 1, 1889, the modern towns of Hanamaki and Hanamaki-Kawaguchi were created within Hienuki District, Iwate. The two towns were merged on April 10, 1929, with the merged municipality retaining the name of Hanamaki. On April 1, 1954, the villages of Yuguchi, Yumoto, Miyanome, Yasawa and Ohta were annexed by Hanamaki. An additional village, Sasama, joined the following year.

In January 2006, Hanamaki merged with the towns of Ishidoriya, Ōhasama, thus dissolving Hienuki District, and with the town of Tōwa from Waga District.[7]

Government

[edit]Hanamaki has a mayor-council form of government with a directly elected mayor and a unicameral city legislature of 25 members. Hanamaki contributes four seats to the Iwate Prefectural legislature. In terms of national politics, the city is part of Iwate 3rd district of the lower house of the Diet of Japan.

Economy

[edit]Agriculture, notably dairy farming dominates the local economy. Hanamaki is also noted for electrical appliances. The area is also noted for its many onsen (hot spring) resorts.[8]

Education

[edit]Fuji University, a private university, is located in Hanamaki.

The city government operates 19 public elementary schools[9] and 11 public junior high schools.[10] There are seven public high schools operated by the Iwate Prefectural Board of Education. The prefecture also operates one special education school.[11]

Transportation

[edit]Railway

[edit]![]() East Japan Railway Company (JR East) - Tōhoku Shinkansen

East Japan Railway Company (JR East) - Tōhoku Shinkansen

![]() East Japan Railway Company (JR East) - Tōhoku Main Line

East Japan Railway Company (JR East) - Tōhoku Main Line

![]() East Japan Railway Company (JR East) - Kamaishi Line

East Japan Railway Company (JR East) - Kamaishi Line

Highway

[edit] Tōhoku Expressway – Hanamaki Parking Area – Hanamaki-minami Interchange – Hanamaki Junction – Hanamaki Interchange

Tōhoku Expressway – Hanamaki Parking Area – Hanamaki-minami Interchange – Hanamaki Junction – Hanamaki Interchange Kamaishi Expressway – Hanamaki Junction – Hanamaki Airport Interchange – Tōwa Interchange

Kamaishi Expressway – Hanamaki Junction – Hanamaki Airport Interchange – Tōwa Interchange National Route 4

National Route 4 National Route 107

National Route 107 National Route 283

National Route 283 National Route 396

National Route 396 National Route 456

National Route 456

Airport

[edit]Local attractions

[edit]Hanamaki is known historically for its many onsen (hot springs). Kenji Miyazawa's various legacies are the old Hanamaki city's other perennial tourist attraction; notably the Miyazawa Kenji Memorial Museum features several exhibitions related to his life and works.[12] The city also has a ski slope.

One of Hanamaki's most notable events is the Hanamaki Matsuri, an annual festival which takes place the second weekend of September and dates back to 1593. The three-day festivities include a dance of over one thousand synchronized traditional dancers; the carrying of over one hundred small shrines; and the parading of a dozen or so large, hand-constructed floats depicting historical, fictional, or mythical scenes and accompanied by drummers, flautists, and lantern-carriers. Of these dances, the most famous is Shishi Odori (dance of the deer). This dance involves men dressing as deer and banging drums.

With the city's recent mergers, Hanamaki now lays claim to its absorbed towns' attractions. Ōhasama is famous for local varieties of traditional Kagura dance. Kagura dancers often appear at area festivals or functions. On a hill above the town of Ōhasama proper stands a statue resembling the wolf-like costumes donned by Hayachine Kagura dancers. Mt. Hayachine, which at 1917 m (6289 ft) is the second highest mountain in Iwate Prefecture, lies in the northeast section of Ōhasama. The area is home to the regionally well-known Edel Wine. In September, the Ōhasama Wine House hosts the annual Wine Festival. Around the time of Japan's Girls' Festival, Ōhasama puts on displays of its collection of dolls, many of which are several hundred years old. Local history suggests that the dolls may have been given to residents of Ōhasama by travelers from Kyoto on their way to trade in Hokkaido. Ishidoriya has a history of brewing sake connected with the Nambu Toji tradition.

International relations

[edit] Berndorf, Austria, since 1965[13]

Berndorf, Austria, since 1965[13] Rutland, Vermont, United States, since October 8, 1986

Rutland, Vermont, United States, since October 8, 1986 Hot Springs, Arkansas, United States, since January 15, 1993

Hot Springs, Arkansas, United States, since January 15, 1993 Xigang District, Dalian, Liaoning, China, friendship city since 2010[14]

Xigang District, Dalian, Liaoning, China, friendship city since 2010[14]

Each of the former towns merged with Hanamaki also conducted exchanges on their own, most of which have been taken up by the new Hanamaki city. Ōhasama was paired Berndorf. Mt. Hayachine is home to a particular species of edelweiss, called Hayachine Usuyukiso, which grows exclusively on Mt. Hayachine. It was because of this flower that mountain climbers from Ōhasama forged a friendship with those from Berndorf, Lower Austria. Ishidoriya was paired with Rutland, Vermont.

Notable people from Hanamaki

[edit]- El Samurai, professional wrestler[15]

- Kazuhiro Hatakeyama, professional baseball player[16]

- Tetsugoro Yorozu, painter[17]

- Koi Ikeno, manga artist[18]

- Masanori Ito (music critic)[19]

- Shunkichi Kikuchi, photographer[20]

- Kenji Miyazawa, writer[21]

- Shohei Ohtani, professional baseball player

References

[edit]- ^ Hanamaki City official statistics

- ^ 詳細データ 岩手県花巻市. 市町村の姿 グラフと統計でみる農林水産業 (in Japanese). Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2017.

- ^ Hanamaki climate data

- ^ 観測史上1~10位の値(年間を通じての値). JMA. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値). JMA. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ Hanamaki population statistics

- ^ Hanamaki City Home page:Yokoso! Hanamaki Archived 2017-06-19 at the Wayback Machine (in Japanese)

- ^ Campbell, Allen; Nobel, David S (1993). Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha. p. 497. ISBN 406205938X.

- ^ Hanamaki city home page: List of elementary schools Archived 2017-11-09 at the Wayback Machine(in Japanese)

- ^ Hanamaki city home page: List of junior high schools Archived 2017-11-09 at the Wayback Machine(in Japanese)

- ^ Hanamaki Seifu Shien-Gakko (in Japanese)

- ^ Organization, Japan National Tourism. "Miyazawa Kenji Memorial Museum | Travel Japan - Japan National Tourism Organization (Official Site)". Travel Japan. Retrieved 2024-05-18.

- ^ "Verein Städtepartnerschaften der Stadt Berndorf" (in German). Official home page of Stadt Berndorf. 2005. Retrieved 12 December 2015.

- ^ "International Exchange". List of Affiliation Partners within Prefectures. Council of Local Authorities for International Relations (CLAIR). Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- ^ World of Wrestling profile

- ^

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference (Minors)

- ^ ["Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Biography on Iwate Prefectural home page] - ^ Hanamaki, Iwate at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- ^ "伊藤政則 - Tower Records Online".

- ^ ["Kikuchi Shunkichi". Nihon shashinka jiten (日本写真家事典) / 328 Outstanding Japanese Photographers. Kyoto: Tankōsha, 2000. ISBN 4-473-01750-8

- ^ Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan article "Miyazawa Kenji" (p. 222–223). 1983. Tokyo: Kodansha.

External links

[edit] Hanamaki travel guide from Wikivoyage

Hanamaki travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official Website (in Japanese)

Hanamaki, Iwate

View on GrokipediaGeography

Topography and hydrography

Hanamaki City spans 908.32 square kilometers, encompassing the fertile alluvial plains of the Kitakami Basin in central Iwate Prefecture, Japan.[2] The city's topography is characterized by low-lying flatlands in its central and eastern sectors, with elevations averaging around 79 meters above sea level, transitioning westward into the rugged Ou Mountains and eastward into the elevated Kitakami Highlands.[7] [1] These surrounding mountain ranges, reaching peaks over 2,000 meters, form natural barriers that influence local drainage patterns and contribute to the city's varied relief, including foothills and valleys suitable for forestry and limited upland agriculture.[8] The Kitakami River, Japan's fourth-longest waterway at 249 kilometers, dominates the hydrography of Hanamaki, flowing northward through the city and depositing nutrient-rich sediments that underpin the region's agricultural productivity.[9] Tributaries such as the Isawa River integrate into this system, forming a dendritic drainage network that irrigates the plains while channeling runoff from the adjacent highlands; this configuration has historically enabled rice and apple cultivation but also exposes lowlands to periodic inundation from upstream precipitation.[10] The river basin's morphology, shaped by Quaternary fluvial deposition over tectonic substrates, supports groundwater recharge essential for local water supply.[11] Geologically, Hanamaki lies within the volcanic arc of northeastern Honshu, influenced by subduction-related magmatism from nearby edifices like Mount Iwate, which exhibits ongoing activity including tremors and minor eruptions as recently as 1961.[8] The subsurface features Neogene sedimentary rocks overlain by volcanic tuffs and lavas, contributing to soil fertility yet heightening vulnerability to seismic events; the area records high earthquake frequency, with over 22 events exceeding magnitude 7 since 1900, reflecting its position in the active Japan Trench forearc.[12] [13] These dynamics underscore the interplay between erosional landforms and endogenous processes in maintaining the landscape's stability and resource potential.[14]Climate

Hanamaki experiences a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa), characterized by distinct seasonal variations driven by its inland location in northern Honshu. Winters are cold and snowy, with average daily lows in January reaching approximately -6°C (21°F), while summers are warm and humid, featuring average daily highs in July of about 28°C (83°F). These temperature extremes, derived from long-term observations at Hanamaki Airport, support agricultural cycles such as rice paddy preparation in spring and harvest in autumn, though prolonged winter freezes can delay planting.[15][16] Annual precipitation totals around 1,332 mm, with the majority falling as rain during the wetter summer months, particularly September, which averages over 150 mm. Winter snowfall accumulates significantly, with January seeing the highest frequency of snow days and average monthly totals exceeding 70 cm in depth at times, impacting road accessibility and requiring routine snow clearance for daily commuting and local farming activities. Compared to Japan's national average annual precipitation of about 1,700 mm, Hanamaki's lower totals reflect regional aridity influences from Siberian air masses in winter.[15][16][16] Over the past three decades (1991–2020), mean annual temperatures have averaged 9.4°C, showing minimal deviation from earlier 30-year normals, with slight increases in summer highs but stable winter lows. Precipitation patterns have remained consistent, with no significant shifts in annual totals or snowfall depth beyond interannual variability, as recorded in regional meteorological datasets; this stability contrasts with wetter coastal areas in Tohoku, where typhoon influences amplify rainfall. Such patterns causally underpin reliable growing seasons for temperate crops like apples, while necessitating adaptive measures like heated greenhouses during occasional late frosts.[15][16]Neighboring municipalities

Hanamaki borders eight municipalities entirely within Iwate Prefecture, encompassing a mix of urban centers, rural towns, and mountainous areas that define its central position on the Kitakami Plain and adjacent highlands.[17] To the north lie Morioka, the prefectural capital, and Shizukuishi; northwest is Nishiwaga; northeast are Shiwa and Kitakami; east-southeast is Miyako; and to the south are Ōshū and Tōno.[17] These boundaries support inter-municipal cooperation in resource management, particularly along the Kitakami River, which delineates parts of the shared frontier with Kitakami and enables coordinated agricultural and flood control efforts in the basin. Hanamaki and Kitakami, as adjacent urban hubs, form the nucleus of the Kitakami-Hanamaki metropolitan area, fostering economic linkages in manufacturing and distribution without formal administrative merger. The southern borders with Tōno and Ōshū connect to broader southern Iwate corridors, aiding seasonal labor and commodity flows in agriculture-dominated regions.[17]Demographics

Population trends and statistics

As of the 2020 Japanese census, Hanamaki's population stood at 93,193 residents.[18] By 2023, this figure had declined to 91,404, marking a decrease of 1,278 from the previous year.[19] The city's population peaked in the mid-1980s at approximately 106,747 before entering a sustained downward trajectory, with decennial census data showing 101,438 in 2010 and 97,702 in 2015.[20] This pattern aligns with broader rural depopulation trends in Japan, driven primarily by natural decrease exceeding modest social inflows. Hanamaki's population density was 102.6 persons per square kilometer as of 2020, across an area of 908.4 km², indicating a dispersed settlement pattern with an urban core surrounded by extensive rural zones.[18] In 2023, natural population change registered a deficit of 1,193 persons, as deaths outpaced births amid an aging demographic structure.[21] Social dynamics showed a slight net gain of 46 persons, with 2,535 inflows against 2,489 outflows, though prior years have seen net out-migration contributing to the overall contraction.[21][19]| Year | Population | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 101,438 | Census data[20] |

| 2015 | 97,702 | Census data[20] |

| 2020 | 93,193 | Census data[18] |

| 2023 | 91,404 | Municipal estimate[19] |

Social composition

Hanamaki's population is ethnically homogeneous, consisting almost exclusively of Japanese nationals, with foreign citizens representing just 0.4% or approximately 373 individuals as of the 2020 census.[18] The age structure highlights an advanced aging profile typical of rural Japan, where 34.8% of residents were 65 years or older, 51.1% were aged 18 to 64, and 14% were under 18 according to the 2020 national census. This distribution, with over one-third in the elderly cohort, stems from prolonged low fertility rates and net out-migration of younger demographics, patterns documented across Tohoku region's municipalities.[22] Females outnumber males, comprising 52.3% of the population compared to 47.7% males in 2020 data.[23] Household compositions reflect this aging trend, featuring a growing share of single-elderly and elderly couple households alongside nuclear families; census figures indicate single-person households at around 28% of total households, with elderly-inclusive nuclear families and couples forming substantial portions amid an overall average household size of approximately 2.5 persons.[24][25]History

Origins and feudal era

Archaeological evidence indicates human habitation in the Hanamaki area during the Jōmon period, with artifacts from sites such as the Kudano ruins showcasing cord-marked pottery and tools associated with hunter-gatherer societies.[26] The Hanamaki City Museum preserves these relics, underscoring the region's prehistoric settlement patterns tied to the resource-rich Kitakami River basin, where natural topography supported semi-sedentary communities reliant on foraging and early resource management.[27] In the feudal era, Hanamaki fell under the control of the Morioka Domain (Morioka-han), governed by the Nanbu clan as a tozama daimyō domain during the Edo period (1603–1868).[1] Hanamaki Castle, positioned on a plateau along the Kitakami River, served as the domain's southern fortress, with fortifications documented in Edo-period drawings dividing the site into honmaru (main keep area), ninomaru (second enclosure), and sanomaru (third enclosure) for defensive administration.[28] Local retainers, including the Kita clan under figures like Kita Shōsai, managed the castle as a hub for samurai oversight, enforcing domain policies amid the one-domain-one-castle principle, though Hanamaki retained its role as an exceptional southern outpost.[29] Agricultural development in the fertile Kitakami Plain drove economic stability, with rice paddies and irrigation systems enabling surplus production that sustained samurai stipends and peasant labor under the domain's kokudaka (assessed yield) system, estimated at around 200,000 koku for Morioka-han overall.[1] This agrarian base, combined with the area's strategic location facilitating oversight of trade routes and Emishi-descended populations, reinforced Nanbu authority until the domain's abolition in 1871 via the hanseki hōkan policy.[28]Meiji and Taisho periods

With the implementation of Japan's modern town and village system on April 1, 1889 (Meiji 22), Hanamaki was formally established as a town, merging prior administrative units in the region and marking a transition from feudal structures to centralized municipal governance.[30][31] This reform facilitated local administration amid broader Meiji-era policies aimed at national unification and economic modernization, including land tax revisions that incentivized private ownership and agricultural productivity in rice-producing areas like the Kitakami Plain.[30] The opening of Hanamaki Station on the Tōhoku Main Line in 1890 connected the town to Morioka and southern routes, enabling efficient transport of agricultural goods such as rice and stimulating trade with urban centers.[31] This infrastructure development causally drove economic expansion by reducing isolation, attracting merchants, and supporting population influx from rural hinterlands, shifting Hanamaki from subsistence farming toward a more market-oriented agrarian base integrated into national rail networks. During the Taishō period (1912–1926), local agricultural advancements emerged, notably through figures like Kenji Miyazawa, who from 1918 taught farmers improved fertilization methods and crop techniques at Hanamaki Agricultural School, aiming to enhance yields in the face of soil challenges in northern Iwate.[32] Concurrently, hot spring tourism gained traction with the 1920 establishment of a major resort by Kunio Kindaichi, drawing on ancient sources like Dai Onsen to develop accessible bathing facilities and promote Hanamaki as a regional wellness destination amid rising domestic travel.[33] These efforts reflected Taishō-era emphases on scientific farming and leisure infrastructure, fostering gradual diversification beyond pure agriculture while infrastructure expansions sustained steady population and economic growth.[32]Showa era and post-war growth

Following World War II, Hanamaki participated in Japan's broader post-war reconstruction, which emphasized rapid industrialization and infrastructure expansion to restore economic vitality. Labour-intensive factories emerged in rural areas of Iwate Prefecture, including Hanamaki, during this reconstruction phase, supporting local manufacturing amid national recovery efforts.[34] Municipal mergers in the mid-1950s, aligning with nationwide consolidations to streamline administration and foster development, expanded Hanamaki's jurisdiction by incorporating adjacent villages. This process, part of the "Great Showa Mergers" era peaking around 1955-1956, increased the city's administrative efficiency and resource base for growth.[35] A further merger on January 1, 2006, integrated the towns of Tōwa, Ishidoriya, and Ōhasama, significantly enlarging Hanamaki's area to approximately 459 square kilometers and boosting its population beyond 100,000. Infrastructure advancements accelerated in the 1960s, exemplified by the completion of Hanamaki Airport in 1964, which provided a 1,200-meter runway initially and improved regional connectivity for commerce and travel.[36] This development coincided with Japan's high-growth period (1955-1973), during which national policies drove export-oriented manufacturing and urban planning, enabling modest population stabilization in Hanamaki around 100,000-105,000 residents from 1960 to 1980 despite rural outflows.[37] Economic expansion tied to these policies emphasized light industry and agriculture processing, though the city's growth remained tempered by its inland Tohoku location compared to coastal hubs.[38]2011 Tōhoku earthquake response and recovery

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake struck on March 11 with a magnitude of 9.0 off Japan's Pacific coast, generating intense shaking across Iwate Prefecture but sparing inland Hanamaki from tsunami inundation due to its approximately 100 km distance from the epicenter and coastline. Hanamaki's infrastructure demonstrated resilience, with the city's airport rapidly repurposed as a regional logistics hub for relief operations, enabling the influx of supplies and personnel without prolonged disruptions from structural failures. This operational continuity stemmed from Japan's nationwide seismic retrofitting mandates, which minimized collapse risks in non-coastal zones despite ground accelerations reaching levels sufficient for precautionary evacuations.[39] Hanamaki Airport facilitated critical medical evacuations, airlifting 191 patients from devastated coastal sites to its facilities by March 18, with 16 subsequently transferred to hospitals beyond Iwate Prefecture via coordinated Self-Defense Forces and civilian aircraft. The airport suspended commercial passenger services temporarily but resumed relief-focused operations within days, handling military and humanitarian flights around the clock alongside nearby facilities like Yamagata and Fukushima airports. This swift pivot—unhindered by tsunami-related submersion or extensive runway damage—underscored Hanamaki's causal advantage as an elevated inland node, allowing it to bypass the port and airfield closures plaguing Pacific-facing sites.[39][40] Recovery in Hanamaki progressed through decentralized logistics, leveraging the airport's intact runways for sustained aid distribution and patient triage, which alleviated pressure on overburdened coastal medical systems. Economic indicators for the city reflected this, with temporary halts in manufacturing and transport yielding to rebound as national supply chains stabilized by mid-2011, supported by government injections exceeding 16 trillion yen in reconstruction funds that indirectly bolstered inland hubs like Hanamaki. Pre-disaster investments in earthquake-resistant infrastructure, including reinforced bridges and utilities, causally enabled this phase by limiting repair needs to minor seismic retrofits rather than wholesale rebuilding.[41][42]Government and administration

Municipal structure

Hanamaki employs a mayor-council system of local government, as stipulated under Japan's Local Autonomy Law, with an elected mayor serving as the chief executive responsible for policy implementation and administrative oversight. The current mayor, Tōichi Ueda, born in 1954, has held the position since 2014 across three terms, with his latest election in January 2022 securing a four-year term ending January 25, 2026.[43][44] Ueda announced his intention not to seek re-election in October 2025, citing term limits and a desire to allow citizen selection of successors.[45] The unicameral city council, comprising 26 members elected every four years, exercises legislative authority, including approving the annual budget, enacting ordinances, and overseeing municipal decisions.[46] Decision-making involves the mayor proposing policies and budgets, which the council reviews and votes on; for instance, supplemental budgets for initiatives like AI security cameras were approved via council sessions in 2025.[47] The executive structure includes a vice mayor appointed by the mayor and various departments under the Comprehensive Policy Department, Regional Promotion Department, and others, handling daily operations.[48] Administratively, Hanamaki is subdivided into approximately 100 gyōseiku (administrative districts), which facilitate community governance, voting organization, and local coordination on issues like infrastructure and events.[49][50] These districts, such as Tsuchizawa No. 7 or Nakuchi No. 1, enable resident input through community councils and support prefectural-level coordination on shared priorities like disaster preparedness and economic development within Iwate Prefecture. Budget allocations emphasize fiscal efficiency and key municipal needs, with the FY2023 general account totaling around 50 billion yen, prioritizing social welfare (over 30% of expenditures), education, and infrastructure amid declining population pressures.[51] Recent plans highlight facility management optimization, regional revitalization projects, and support for aging infrastructure, with decisions guided by the city's comprehensive plan focusing on sustainable growth and community welfare.[52][53]Fiscal and policy overview

Hanamaki's general account initial budget for fiscal year 2025 (Reiwa 7) totaled 58.178 billion yen, the highest since the 2006 municipal merger and representing a 5.5% increase, or 3.025 billion yen, over the prior year.[54] [55] This expansion reflects prioritized allocations under a "selection and concentration" approach, emphasizing key areas amid stable revenue from local taxes such as fixed asset taxes, alongside national grants and local allocation taxes.[56] Fiscal policies post-2011 Tōhoku earthquake prioritize disaster preparedness and rural revitalization, integrated into the city's comprehensive strategy for town, people, and work creation. The regional disaster plan, revised in April 2023 per the Basic Act on Disaster Control Measures, delineates operational frameworks for emergency response, resource allocation, and citizen protection to mitigate earthquake and related risks prevalent in Iwate Prefecture.[57] Complementing this, the National Resilience Regional Plan, updated in May 2025, shifts emphasis from reactive reconstruction to proactive prevention, risk reduction, and swift recovery, aiming to curb long-term fiscal burdens from recurrent disasters.[58] Rural revitalization efforts, embedded in the second-phase local creation strategy, target population stabilization and economic diversification through enhanced local industries and community resilience.[21] Performance metrics underscore fiscal efficiency, with the FY2024 settlement showing a real public debt service ratio of 9.2%—below the 25% threshold triggering reconstruction plans—and future burden ratio meeting all soundness criteria, evidencing prudent debt management and capacity for sustained service delivery without excessive leverage.[59] These indicators, derived from standardized local fiscal assessments, suggest effective resource allocation yielding low default risk and operational stability, though direct service metrics like welfare or infrastructure response times remain tied to broader prefectural recovery outcomes rather than isolated municipal overperformance.[60]Economy

Agriculture and primary production

Hanamaki's agriculture leverages the fertile soils and ample water supply of the Kitakami Plain, enabling high productivity in staple crops through natural irrigation from surrounding rivers and mountains.[1] This geographic positioning supports extensive paddy fields and orchards, contributing to the region's role in Tohoku's grain and fruit output.[61] Rice remains a cornerstone crop, with Hanamaki exemplifying structured paddy farming practices amid Tohoku's cold climate adaptations.[61] Iwate Prefecture, encompassing Hanamaki's prime alluvial lands, harvested 249,100 metric tons of rice in 2023, ranking it among Japan's top producers by volume share.[62] Apples follow as a key fruit, cultivated via cooperative efforts like those of JA Iwate Hanamaki, though yields have fluctuated sharply—dropping up to 40% in frost-affected years due to late-spring temperature swings.[63] Vegetables, including cabbages and root crops, thrive on the plain's flat terrain, supplementing rice rotations for diversified primary production.[64] Local rice also feeds sake brewing, a tradition rooted in Hanamaki's pure groundwater and Nambu Toji mastery, where brewers from the area consult at over 300 nationwide facilities.[65] At least two active breweries, including Kawamura Shuzoten in Ishidoriya district, produce premium varieties using over 90% prefectural rice, emphasizing crisp profiles from fermented local grains.[66][67] Empirical pressures include acute labor shortages from an aging workforce—Japan's agricultural core workers averaged over 65 years old by 2020, with farm households declining 44% since 2005—and successor scarcity in orchards.[68][69] These drive mechanization shifts, such as rice-transplanting robots and unmanned tractors, to sustain yields amid depopulation.[70][71]Industry and manufacturing

Hanamaki's manufacturing sector encompasses food processing, precision machinery, and general machinery production, with 380 establishments employing 8,344 workers as of 2022, marking a 3.4% increase from the prior year.[72][73] The sector accounts for roughly 20% of the local workforce, driven by post-war infrastructure development including industrial parks established in the 1970s.[73] Shipment values totaled 244.2 billion yen in 2022, a 4.6% rise and the highest since 2002, reflecting resilience amid regional economic shifts.[74] Food processing firms, numbering 83, leverage proximity to agricultural outputs for secondary transformation, though distinct from primary production.[72] Machinery subsectors dominate, with precision and general equipment firms like Nitto Kogyo Corporation's Hanamaki Plant (specializing in metal products) and Nissei Electric's facility contributing to high productivity.[75][76] Other notable operators include TSD K.K. and Sato Seiki Co., Ltd., focused on industrial machinery.[77] Post-World War II growth accelerated through targeted zoning, such as the Hanamaki First Industrial Park opened in 1974, which supported expansion in mechanical industries amid Japan's broader economic miracle.[78] By the 1980s, employment peaked before a decline, followed by stabilization via SME specialization in value-added niches like precision components, aligning with national trends away from heavy industry toward agile manufacturing clusters.[79] Local associations, including the Hanamaki Precision Machinery Industry Association, have facilitated this transition by promoting technological upgrades and firm collaborations.[80]Services and tourism

The services sector, including retail, hospitality, and tourism, forms a cornerstone of Hanamaki's economy, leveraging the city's hot springs and cultural sites to generate visitor-driven revenue. Annual tourist inflows to Hanamaki averaged approximately 2 million visitors in the late 2010s, with 2.01 million recorded in 2018, reflecting a stabilization following the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake's initial disruptions to regional travel.[81] This volume underscores tourism's role as an economic multiplier, supporting ancillary services like accommodations and local commerce, though precise GDP attribution remains embedded within Iwate Prefecture's broader tertiary sector, which mirrors Tohoku's 68.5% share of regional output in fiscal year 2016.[82] Pre-2011 visitor numbers hovered around similar levels, with a noted 7% decline from 2014's estimated 2.16 million to 2018, attributable partly to lingering earthquake reputational effects and demographic shifts in domestic travel rather than structural damage in Hanamaki itself.[83] Post-recovery, foreign tourism has accelerated, particularly to Hanamaki Onsen, where 71,000 international visitors arrived in the fiscal year ending March 31, 2025—about 60,000 from Taiwan—fueled by targeted charter flights and promotional efforts.[84] These inflows demonstrate causal linkages to improved accessibility via Iwate Hanamaki Airport, which handled 19,402 inbound foreign entries in 2019, enabling efficient distribution of tourists to onsen facilities and amplifying spending in hospitality.[85] Retail and hospitality employment trends align with tourism rebound, with steady demand in accommodations reflecting annual visitor volumes exceeding 2 million, as evidenced by sustained operations in onsen resorts that adapted post-2011 through diversified tour offerings.[86] The airport's connectivity to major hubs like Tokyo and Osaka further bolsters these sectors by reducing travel barriers, correlating with increased service-oriented jobs amid Tohoku's emphasis on inbound recovery strategies.[82]Education

Primary and secondary education

Hanamaki maintains 16 public elementary schools and 11 public junior high schools under municipal oversight, serving compulsory education from ages 6 to 15.[87][88] These institutions follow the national curriculum standards established by Japan's Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), emphasizing core subjects like Japanese language, mathematics, science, and social studies, with integrated moral education and physical activities. Enrollment in junior high schools stood at 2,140 students as of the latest MEXT survey data.[88] High schools in Hanamaki number six, including five public institutions operated by the Iwate Prefectural Board of Education—Hanamaki North, Hanamaki South, Hanamaki Agricultural, Hanamaki North Aogun, and Osaku—and one private school, Hanamaki East.[89] These provide upper secondary education with specialized tracks in academics, agriculture, and vocational training, aligned with prefectural guidelines that incorporate local economic needs such as farming and manufacturing. Extracurricular activities include sports clubs and cultural programs, often reflecting Hanamaki's agricultural heritage through initiatives like school farm projects. Academic outcomes, as measured by the national academic ability and learning situation survey, show Hanamaki's elementary and junior high students scoring below both national and Iwate prefectural averages across Japanese language, mathematics, and all tested subjects in the 2024 administration.[90] Graduation rates at the compulsory level approach 100%, with high school advancement rates exceeding 98% prefecture-wide, indicative of strong progression to upper secondary education.[91] Facilities across schools include standard classrooms, gyms, and libraries, with some rural elementary schools featuring consolidated campuses to optimize resources amid declining birth rates.Higher education and cultural institutions

Fuji University, a private institution founded in 1965 in Hanamaki, offers undergraduate and graduate programs primarily in economics and management.[92] The Hanamaki Nursing School provides vocational training in nursing and healthcare, emphasizing practical skills for regional medical needs. These facilities support post-secondary education accessible to local residents, with no direct branches of Iwate University present in the city. Public libraries in Hanamaki, including branches like the Ohasama Library, serve community reading and research needs, though detailed collection sizes remain undocumented in available records. The Hanamaki City Museum maintains collections of historical and cultural artifacts from the region, including materials from former districts like Hienuki and Waga, open to the public for educational purposes.[29] The Hanamaki City Comprehensive Cultural Properties Center, established on May 22, 2011, functions as a central repository for preserving and exhibiting local cultural assets, facilitating public access and awareness programs.[93] Miyazawa Kenji heritage sites integrate educational components, such as interactive exhibits at the Fairy Tales Village's Kenji's School, where visitors engage with the author's literature, astronomy, and agrarian themes through hands-on activities tied to his Hanamaki upbringing.[94] These institutions promote accessibility via standard public hours and low entry fees, supporting cultural education without overlap into tourism promotion.Transportation

Railway infrastructure

Hanamaki's railway network is operated by East Japan Railway Company (JR East) and centers on the Tohoku Main Line, which provides conventional rail connectivity northward to Morioka and southward toward Sendai, and the Kamaishi Line, extending to coastal destinations including Kamaishi for both regular and seasonal tourist services such as the former SL Ginga steam excursions.[95][96] Hanamaki Station serves as the principal junction for these lines, handling local and regional passenger traffic with platforms accommodating multiple tracks for efficient transfers.[97] High-speed access is provided via Shin-Hanamaki Station, situated about 6 kilometers northwest of Hanamaki Station along the Kamaishi Line, which connects directly to the Tohoku Shinkansen for services to Tokyo (approximately 2.5 hours via Hayabusa trains) and northern Tohoku cities.[97][98] The station opened on March 14, 1985, coinciding with expansions in Shinkansen infrastructure to enhance regional links following the line's initial phases in the early 1980s.[99] Passenger usage underscores the infrastructure's role in daily commuting and tourism; in fiscal year 2021, Hanamaki Station averaged 2,941 boarding passengers daily, with roughly 83% on commuter passes reflecting local workforce travel.[100] By fiscal year 2022, this figure stood at approximately 2,952 daily boardings, comprising over half of Hanamaki's total rail patronage.[101] Shin-Hanamaki, focused on intercity Shinkansen transfers, sees lower local boarding volumes—around 900 daily in earlier fiscal data—but supports broader throughput for long-distance travelers.[102] The lines primarily emphasize passenger operations, with freight handled on the Tohoku Main Line's broader corridor rather than localized at Hanamaki stations.Highway network

The Tōhoku Expressway (E4), the longest expressway in Japan spanning 679.5 km, traverses Hanamaki, providing essential north-south connectivity through Iwate Prefecture. Key facilities include the Hanamaki Interchange, Hanamaki-minami Interchange, and Hanamaki Junction, which links to the Kamaishi Expressway for access to coastal regions. In March 2024, the Hanamaki PA Smart Interchange opened at the Hanamaki Parking Area, located 7.9 km north of the Kitakami-Ezuriko Interchange, improving local entry and exit efficiency for shorter trips.[103][104] National highways complement the expressway network, with Route 4 serving as a major parallel arterial road handling regional freight and passenger traffic. Route 283 connects Hanamaki to Kamaishi over 89.3 km, supporting goods movement from inland agricultural areas to ports. Expressway sections in the region experience lower accident rates than general roads, with fatal and injury incidents roughly one-tenth as frequent due to controlled access and design standards. Traffic volumes on the Tōhoku Expressway exceed 330,000 vehicles monthly across Tohoku segments, underscoring its role in efficient logistics for local industries.[105][106][107]

Hanamaki Airport

Hanamaki Airport (IATA: HNA, ICAO: RJSI) operates primarily as a regional facility serving domestic routes to key Japanese cities such as Tokyo, Osaka (via Itami and Kansai), Nagoya (Komaki), Fukuoka, Kobe, and Sapporo (New Chitose).[108] Airlines including Fuji Dream Airlines and Japan Airlines provide scheduled services, with a focus on connecting Iwate Prefecture to central and southern Japan. Seasonal charter international flights link to Taipei (Taoyuan), Taiwan, supporting limited inbound tourism.[109] The airport handles modest volumes of cargo, primarily tied to local agricultural and light industrial exports from the region.[110] The facility features a single runway (02/20) measuring 2,500 meters (8,202 feet) in length, surfaced with asphalt concrete, capable of accommodating mid-sized jet aircraft following its extension in 2005.[111] This upgrade enhanced operational capacity for disaster response and commercial use, though no major expansions have occurred since. In typical operations, the airport supports around 10-12 daily flights, emphasizing efficiency for regional connectivity rather than high-volume hub functions.[112] Following the March 11, 2011, Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, Hanamaki Airport quickly resumed full operations and served as a critical hub for relief efforts, hosting disaster response aircraft and facilitating aeromedical evacuations. By March 18, 191 patients had been airlifted there for transfer to external medical facilities, with extended hours (07:00-19:00) and high arrival rates averaging 8.64 aircraft per hour in the initial 72 hours.[39] [113] Economically, the airport bolsters tourism to Iwate's onsen districts and natural sites by providing direct access, positioning itself as an international gateway that drives visitor inflows and supports regional revitalization through inbound travel.[114]Culture

Festivals and traditions

The Hanamaki Festival, an annual event spanning the second Friday to Sunday in September, centers on traditional performances such as drum and shamisen ensembles, deer dances, Kagura Gongen-mai, and Hanamaki Bayashi dances, which originate from ancient Shinto rituals honoring deities and agrarian prosperity.[115] [116] Established in 1593 under Kita Shosai, the city's founder, the festival maintains over 430 years of continuity, featuring mikoshi parades and floats that reflect historical community bonds in rice-farming cycles.[117] [118] Complementing these are seasonal rites like the Oohasama Andon Festival, a 200-year-old Obon observance in late summer involving paper lanterns floated to commemorate ancestors, symbolizing spiritual passage and harvest gratitude in rural Hanamaki districts.[119] The Ishidoriya Festival, held September 8–10 in the Yoshiji area, preserves localized Shinto processions and folk dances handed down through generations, linking to pre-modern agrarian calendars.[120] Summer fireworks displays, such as the Pageant of Light and Sound Fireworks Fantasy Festival typically in late August, integrate modern spectacle with traditional viewing customs, though events have faced cancellations due to weather.[121] These traditions, including crafts like the 200-year-old Hanamaki umbrellas used in ritual processions, endure amid Hanamaki's demographic challenges, with local efforts sustaining participation through community organizations despite rural population declines.[122]Literary and artistic heritage

Hanamaki is the birthplace of Miyazawa Kenji (1896–1933), a poet, novelist, and Buddhist thinker whose works drew heavily from the region's natural landscapes, rural hardships, and cosmic themes.[123] Born into a prosperous pawnbroking family in the city, Miyazawa experienced personal tragedy, including the death of his sister Toshiko in 1922, which profoundly shaped his literary output focused on empathy, impermanence, and agrarian reform. His writings, often blending folklore with scientific observation—reflecting his studies in geology, botany, and astronomy—portrayed an idealized "Ihatov" realm inspired by Iwate's Kitakami River valley and volcanic terrain.[124] Among Miyazawa's most enduring works is the novella Night on the Galactic Railroad (1927, published posthumously in 1934), a metaphysical tale of two boys journeying through a starlit train, symbolizing death and enlightenment; it has sold over 1 million copies in Japan and inspired local landmarks like the "Galaxy Station" exhibit.[125] Other key pieces include the short stories Gauche the Cellist (1926) and Windy Matasaburo (1934, posthumous), which evoke Tohoku's windswept fields and childlike wonder, alongside tanka poetry collections like Spring and Asura (1924).[126] These narratives, initially overlooked during his lifetime due to their experimental style and pacifist undertones, gained acclaim after World War II for their humanistic depth, influencing modern Japanese literature with annual publications exceeding 100,000 volumes combined by the 2010s.[123] Miyazawa's legacy manifests in Hanamaki through dedicated institutions preserving his artifacts and worldview. The Miyazawa Kenji Memorial Museum, opened in 1983 on Mount Koshio, houses over 10,000 items including manuscripts, geological specimens, and agricultural tools, organized into exhibits on science, art, religion, and space to illustrate his interdisciplinary pursuits.[127] The adjacent Ihatov Center collects scholarly papers and hosts researcher exchanges, while the Miyazawa Kenji Fairy Tale Village recreates settings from his stories, drawing 200,000 visitors annually pre-2011 earthquake and fostering adaptations like the 1985 animated film of Night on the Galactic Railroad, viewed by millions and credited with elevating his global profile.[128] [125] Beyond Miyazawa, Hanamaki's artistic heritage includes traditional Tohoku crafts like kokeshi dolls and sarashi weaving, rooted in local silk production since the Edo period, though these lack prominent literary ties and remain secondary to his overshadowing influence.[129]Tourism and attractions

Onsen and natural sites

Hanamaki Onsenkyo, the primary hot spring complex in the city, encompasses 12 individual onsen facilities clustered along the Kitakami River valley, drawing from geothermal sources with abundant flow rates exceeding 1,000 liters per minute in aggregate.[130] These springs predominantly yield alkaline simple hot spring waters, classified under Japan's onsen standards for their pH values typically ranging from 8.5 to 9.2, which promote skin smoothing due to the high alkalinity dissolving soap residues and sebum.[131][132] Facilities such as Kashoen and Yuukaen Ryokan feature multiple bath varieties, including open-air rotenburo sourced directly from the springs, with the waters noted for being colorless, odorless, and tasteless, minimizing irritation for extended soaking.[133] Approximately eight major ryokan, including Hotel Hanamaki, Hotel Koyokan, and Ryokan Hiromitei, operate within the core area, accommodating over 1,000 guests nightly during peak seasons based on combined capacity estimates.[134] The Ou Mountains, encompassing elevations within Hanamaki's northern reaches, host natural parks like the Mount Hayachine area, a designated quasi-national park zone spanning rugged terrain up to 1,914 meters.[135] Hiking trails on Mount Hayachine, totaling around 10 kilometers of marked paths, ascend through mixed forests of beech and fir, with seasonal biodiversity highlights including endemic alpine flora such as Hayachine gentian and unique moss species adapted to the granitic soils.[136] These trails support moderate to strenuous day hikes, with annual visitor data indicating several thousand ascents, primarily in summer for wildflower viewing and observation of resident fauna like the Japanese serow and rare avian species.[135] Waterfalls such as Kamabuchi no Taki, fed by mountain streams, add to the geological features, showcasing basalt formations from ancient volcanic activity in the Kitakami Mountains subsystem.[135] Thermal energy in Hanamaki is primarily harnessed through the onsen for bathing and heating, with natural geothermal gradients providing consistent temperatures of 40–50°C at source depths of 1,000–1,500 meters, though large-scale electric generation remains undeveloped locally unlike nearby Hachimantai facilities.[137] This direct utilization sustains year-round operations without supplemental fuels in many ryokan, leveraging the region's volcanic subsurface heat flux estimated at 50–100 mW/m².[138]Historical and modern landmarks

The ruins of Hanamaki Castle, originally constructed in 1591 by Kita Hidechika on the site of the earlier Toyoyasakijō, represent a strategic fortress from the late Sengoku period, with preserved stone walls (ishigaki) and a reconstructed gate maintaining its defensive layout at the base of Mount Shizuki.[139][28] The site, designated as a local historic landmark, has undergone partial restoration to highlight its role as a southern outpost of the Morioka Domain during the Edo period, though the main keep and most wooden structures were dismantled in 1874 following the Meiji Restoration.[140] The Miyazawa family home, known as the birthplace of poet and novelist Kenji Miyazawa (born August 27, 1896), was the original residence of his pawnbroker family in Hanamaki's Kaji-chō district but was destroyed by fire during World War II air raids. Rebuilt twice post-war, the structure now serves as a commemorative site without retaining authentic artifacts from Miyazawa's era, emphasizing interpretive displays over original preservation.[141] Adjacent memorials, including the "Ame ni mo Makezu" poem monument at the family's second home in Sakuramachi—where Miyazawa resided from March 1926 until his death—feature inscribed granite markers erected in the mid-20th century to honor his literary legacy, with annual flower offerings aiding upkeep through public visitation.[142] Modern landmarks include the Miyazawa Kenji Memorial Museum, established in 1982 atop Mount Koshio, which houses curated exhibits of manuscripts, personal effects, and multimedia on Miyazawa's pursuits in astronomy, geology, and Buddhism, funded by local preservation efforts to counter erosion from regional tourism.[143][144] Post-war civic architecture is exemplified by the Hanamaki City Cultural Hall, completed on August 18, 1959, with a capacity for 1,100 seated spectators in its main auditorium, reflecting Japan's rapid reconstruction era through reinforced concrete design and multifunctional use for cultural events.[145] Hanamaki City Hall, a contemporary administrative hub, incorporates post-1950s urban planning to accommodate the city's growth, though specific construction details underscore ongoing maintenance challenges from seismic activity in Iwate Prefecture.[146]International relations

Sister city agreements

Hanamaki maintains sister city agreements with three international partners, focusing on cultural, educational, and economic exchanges rooted in shared historical or thematic ties such as hot springs tourism and community resilience. These relationships, established through formal pacts, have involved reciprocal delegations, student programs, and commemorative events, yielding measurable outcomes like sustained youth exchanges and local business collaborations, though quantifiable economic impacts remain modest and primarily cultural in nature.[147][148] The agreement with Berndorf in Lower Austria dates to 1965, initially linked via a constituent town of Hanamaki and continued post-merger, emphasizing long-term goodwill through periodic visits and community projects.[147] With Hot Springs, Arkansas, United States, formalized on January 15, 1993, due to mutual hot spring heritage, exchanges include annual student delegations, festivals like cherry blossom events, and initiatives such as sake production ties, fostering tourism and educational ties over three decades.[149][150] The pact with Rutland, Vermont, United States, originated in 1985 with Ishidoriya (merged into Hanamaki in 2006) and persists via anniversary celebrations, academic visits, and cultural programs, as evidenced by a 2020 mask donation amid the COVID-19 pandemic and a 2024 35th-anniversary delegation.[151][152][147]| Sister City | Country | Establishment Date | Key Exchange Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berndorf | Austria | 1965 | Community visits and joint projects[147] |

| Hot Springs | United States | January 15, 1993 | Student exchanges, festivals, business collaborations (e.g., sake production)[149][150] |

| Rutland | United States | 1985 (continued post-2006 merger) | Delegations, anniversary events, educational and aid exchanges (e.g., pandemic support)[151][152] |