Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Hydronium

View on Wikipedia

| |||

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name

oxonium

| |||

| Other names

hydronium ion

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| 141 | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| |||

| |||

| Properties | |||

| H3O+ | |||

| Molar mass | 19.023 g·mol−1 | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | undefined | ||

| Conjugate base | Water | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

In chemistry, hydronium (hydroxonium in traditional British English) is the cation [H3O]+, also written as H3O+, the type of oxonium ion produced by protonation of water. It is often viewed as the positive ion present when an Arrhenius acid is dissolved in water, as Arrhenius acid molecules in solution give up a proton (a positive hydrogen ion, H+) to the surrounding water molecules (H2O). In fact, acids must be surrounded by more than a single water molecule in order to ionize, yielding aqueous H+ and conjugate base.

Three main structures for the aqueous proton have garnered experimental support:

- the Eigen cation, which is a tetrahydrate, H3O+(H2O)3

- the Zundel cation, which is a symmetric dihydrate, H+(H2O)2

- and the Stoyanov cation, an expanded Zundel cation, which is a hexahydrate: H+(H2O)2(H2O)4[1][2]

Spectroscopic evidence from well-defined IR spectra overwhelmingly supports the Stoyanov cation as the predominant form.[3][4][5][6][non-primary source needed] For this reason, it has been suggested that wherever possible, the symbol H+(aq) should be used instead of the hydronium ion.[2]

Relation to pH

[edit]The molar concentration of hydronium or H+ ions determines a solution's pH according to

- pH = −log([H3O+]/M)

where M = mol/L. The concentration of hydroxide ions analogously determines a solution's pOH. The molecules in pure water auto-dissociate into aqueous protons and hydroxide ions in the following equilibrium:

- H2O ⇌ OH−(aq) + H+(aq)

In pure water, there is an equal number of hydroxide and H+ ions, so it is a neutral solution. At 25 °C (77 °F), pure water has a pH of 7 and a pOH of 7 (this varies when the temperature changes: see self-ionization of water). A pH value less than 7 indicates an acidic solution, and a pH value more than 7 indicates a basic solution.[7]

Nomenclature

[edit]According to IUPAC nomenclature of organic chemistry, the hydronium ion should be referred to as oxonium.[8] Hydroxonium may also be used unambiguously to identify it.[citation needed]

An oxonium ion is any cation containing a trivalent oxygen atom.

Structure

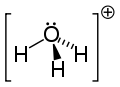

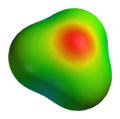

[edit]Since O+ and N have the same number of electrons, H3O+ is isoelectronic with ammonia. As shown in the images above, H3O+ has a trigonal pyramidal molecular geometry with the oxygen atom at its apex. The H−O−H bond angle is approximately 113°,[9][10] and the center of mass is very close to the oxygen atom. Because the base of the pyramid is made up of three identical hydrogen atoms, the H3O+ molecule's symmetric top configuration is such that it belongs to the C3v point group. Because of this symmetry and the fact that it has a dipole moment, the rotational selection rules are ΔJ = ±1 and ΔK = 0. The transition dipole lies along the c-axis and, because the negative charge is localized near the oxygen atom, the dipole moment points to the apex, perpendicular to the base plane.

Acids and acidity

[edit]The hydrated proton is very acidic: at 25 °C, its pKa is approximately 0.[11] The values commonly given for pKaaq(H3O+) are 0 or −1.74. The former uses the convention that the activity of the solvent in a dilute solution (in this case, water) is 1, while the latter uses the value of the concentration of water in the pure liquid of 55.5 M. Silverstein has shown that the latter value is thermodynamically unsupportable.[12] The disagreement comes from the ambiguity that to define pKa of H3O+ in water, H2O has to act simultaneously as a solute and the solvent. The IUPAC has not given an official definition of pKa that would resolve this ambiguity. Burgot has argued that H3O+(aq) + H2O (l) ⇄ H2O (aq) + H3O+ (aq) is simply not a thermodynamically well-defined process. For an estimate of pKaaq(H3O+), Burgot suggests taking the measured value pKaEtOH(H3O+) = 0.3, the pKa of H3O+ in ethanol, and applying the correlation equation pKaaq = pKaEtOH − 1.0 (± 0.3) to convert the ethanol pKa to an aqueous value, to give a value of pKaaq(H3O+) = −0.7 (± 0.3).[13] On the other hand, Silverstein has shown that Ballinger and Long's experimental results [14] support a pKa of 0.0 for the aqueous proton.[15] Neils and Schaertel provide added arguments for a pKa of 0.0 [16]

The aqueous proton is the most acidic species that can exist in water (assuming sufficient water for dissolution): any stronger acid will ionize and yield a hydrated proton. The acidity of H+(aq) is the implicit standard used to judge the strength of an acid in water: strong acids must be better proton donors than H+(aq), as otherwise a significant portion of acid will exist in a non-ionized state (i.e.: a weak acid). Unlike H+(aq) in neutral solutions that result from water's autodissociation, in acidic solutions, H+(aq) is long-lasting and concentrated, in proportion to the strength of the dissolved acid.

pH was originally conceived to be a measure of the hydrogen ion concentration of aqueous solution.[17] Virtually all such free protons are quickly hydrated; acidity of an aqueous solution is therefore more accurately characterized by its concentration of H+(aq). In organic syntheses, such as acid catalyzed reactions, the hydronium ion (H3O+) is used interchangeably with the H+ ion; choosing one over the other has no significant effect on the mechanism of reaction.

Solvation

[edit]Researchers have yet to fully characterize the solvation of hydronium ion in water, in part because many different meanings of solvation exist. A freezing-point depression study determined that the mean hydration ion in cold water is approximately H3O+(H2O)6:[18] on average, each hydronium ion is solvated by 6 water molecules which are unable to solvate other solute molecules.

Some hydration structures are quite large: the H3O+(H2O)20 magic ion number structure (called magic number because of its increased stability with respect to hydration structures involving a comparable number of water molecules – this is a similar usage of the term magic number as in nuclear physics) might place the hydronium inside a dodecahedral cage.[19] However, more recent ab initio method molecular dynamics simulations have shown that, on average, the hydrated proton resides on the surface of the H3O+(H2O)20 cluster.[20] Further, several disparate features of these simulations agree with their experimental counterparts suggesting an alternative interpretation of the experimental results.

Two other well-known structures are the Zundel cation and the Eigen cation. The Eigen solvation structure has the hydronium ion at the center of an H9O+4 complex in which the hydronium is strongly hydrogen-bonded to three neighbouring water molecules.[21] In the Zundel H5O+2 complex the proton is shared equally by two water molecules in a symmetric hydrogen bond.[22] A work in 1999 indicates that both of these complexes represent ideal structures in a more general hydrogen bond network defect.[23]

Isolation of the hydronium ion monomer in liquid phase was achieved in a nonaqueous, low nucleophilicity superacid solution (HF−SbF5SO2). The ion was characterized by high resolution 17O nuclear magnetic resonance.[24]

A 2007 calculation of the enthalpies and free energies of the various hydrogen bonds around the hydronium cation in liquid protonated water[25] at room temperature and a study of the proton hopping mechanism using molecular dynamics showed that the hydrogen-bonds around the hydronium ion (formed with the three water ligands in the first solvation shell of the hydronium) are quite strong compared to those of bulk water.

A new model was proposed by Stoyanov based on infrared spectroscopy in which the proton exists as an H13O+6 ion. The positive charge is thus delocalized over 6 water molecules.[26]

Solid hydronium salts

[edit]For many strong acids, it is possible to form crystals of their hydronium salt that are relatively stable. These salts are sometimes called acid monohydrates. As a rule, any acid with an ionization constant of 109 or higher may do this. Acids whose ionization constants are below 109 generally cannot form stable H3O+ salts. For example, nitric acid has an ionization constant of 101.4, and mixtures with water at all proportions are liquid at room temperature. However, perchloric acid has an ionization constant of 1010, and if liquid anhydrous perchloric acid and water are combined in a 1:1 molar ratio, they react to form solid hydronium perchlorate (H3O+·ClO−4).[citation needed]

The hydronium ion also forms stable compounds with the carborane superacid H(CB11H(CH3)5Br6).[27] X-ray crystallography shows a C3v symmetry for the hydronium ion with each proton interacting with a bromine atom each from three carborane anions 320 pm apart on average. The [H3O] [H(CB11HCl11)] salt is also soluble in benzene. In crystals grown from a benzene solution the solvent co-crystallizes and a H3O·(C6H6)3 cation is completely separated from the anion. In the cation three benzene molecules surround hydronium forming pi-cation interactions with the hydrogen atoms. The closest (non-bonding) approach of the anion at chlorine to the cation at oxygen is 348 pm.

There are also many known examples of salts containing hydrated hydronium ions, such as the H5O+2 ion in HCl·2H2O, the H7O+3 and H9O+4 ions both found in HBr·4H2O.[28]

Sulfuric acid is also known to form a hydronium salt H3O+HSO−4 at temperatures below 8.49 °C (47.28 °F).[29]

Interstellar H3O+

[edit]Hydronium is an abundant molecular ion in the interstellar medium and is found in diffuse[30] and dense[31] molecular clouds as well as the plasma tails of comets.[32] Interstellar sources of hydronium observations include the regions of Sagittarius B2, Orion OMC-1, Orion BN–IRc2, Orion KL, and the comet Hale–Bopp.

Interstellar hydronium is formed by a chain of reactions started by the ionization of H2 into H+2 by cosmic radiation.[33] H3O+ can produce either OH− or H2O through dissociative recombination reactions, which occur very quickly even at the low (≥10 K) temperatures of dense clouds.[34] This leads to hydronium playing a very important role in interstellar ion-neutral chemistry.

Astronomers are especially interested in determining the abundance of water in various interstellar climates due to its key role in the cooling of dense molecular gases through radiative processes.[35] However, H2O does not have many favorable transitions for ground-based observations.[36] Although observations of HDO (the deuterated version of water[37]) could potentially be used for estimating H2O abundances, the ratio of HDO to H2O is not known very accurately.[36]

Hydronium, on the other hand, has several transitions that make it a superior candidate for detection and identification in a variety of situations.[36] This information has been used in conjunction with laboratory measurements of the branching ratios of the various H3O+ dissociative recombination reactions[34] to provide what are believed to be relatively accurate OH− and H2O abundances without requiring direct observation of these species.[38][39]

Interstellar chemistry

[edit]As mentioned previously, H3O+ is found in both diffuse and dense molecular clouds. By applying the reaction rate constants (α, β, and γ) corresponding to all of the currently available characterized reactions involving H3O+, it is possible to calculate k(T) for each of these reactions. By multiplying these k(T) by the relative abundances of the products, the relative rates (in cm3/s) for each reaction at a given temperature can be determined. These relative rates can be made in absolute rates by multiplying them by the [H2]2.[40] By assuming T = 10 K for a dense cloud and T = 50 K for a diffuse cloud, the results indicate that most dominant formation and destruction mechanisms were the same for both cases. It should be mentioned that the relative abundances used in these calculations correspond to TMC-1, a dense molecular cloud, and that the calculated relative rates are therefore expected to be more accurate at T = 10 K. The three fastest formation and destruction mechanisms are listed in the table below, along with their relative rates. Note that the rates of these six reactions are such that they make up approximately 99% of hydronium ion's chemical interactions under these conditions.[32] All three destruction mechanisms in the table below are classified as dissociative recombination reactions.[41]

| Reaction | Type | Relative rate (cm3/s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| at 10 K | at 50 K | ||

| H2 + H2O+ → H3O+ + H | Formation | 2.97×10−22 | 2.97×10−22 |

| H2O + HCO+ → CO + H3O+ | Formation | 4.52×10−23 | 4.52×10−23 |

| H+3 + H2O → H3O+ + H2 | Formation | 3.75×10−23 | 3.75×10−23 |

| H3O+ + e− → OH + H + H | Destruction | 2.27×10−22 | 1.02×10−22 |

| H3O+ + e− → H2O + H | Destruction | 9.52×10−23 | 4.26×10−23 |

| H3O+ + e− → OH + H2 | Destruction | 5.31×10−23 | 2.37×10−23 |

It is also worth noting that the relative rates for the formation reactions in the table above are the same for a given reaction at both temperatures. This is due to the reaction rate constants for these reactions having β and γ constants of 0, resulting in k = α which is independent of temperature.

Since all three of these reactions produce either H2O or OH, these results reinforce the strong connection between their relative abundances and that of H3O+. The rates of these six reactions are such that they make up approximately 99% of hydronium ion's chemical interactions under these conditions.

Astronomical detections

[edit]As early as 1973 and before the first interstellar detection, chemical models of the interstellar medium (the first corresponding to a dense cloud) predicted that hydronium was an abundant molecular ion and that it played an important role in ion-neutral chemistry.[42] However, before an astronomical search could be underway there was still the matter of determining hydronium's spectroscopic features in the gas phase, which at this point were unknown. The first studies of these characteristics came in 1977,[43] which was followed by other, higher resolution spectroscopy experiments. Once several lines had been identified in the laboratory, the first interstellar detection of H3O+ was made by two groups almost simultaneously in 1986.[31][36] The first, published in June 1986, reported observation of the Jvt

K = 1−

1 − 2+

1 transition at 307192.41 MHz in OMC-1 and Sgr B2. The second, published in August, reported observation of the same transition toward the Orion-KL nebula.

These first detections have been followed by observations of a number of additional H3O+ transitions. The first observations of each subsequent transition detection are given below in chronological order:

In 1991, the 3+

2 − 2−

2 transition at 364797.427 MHz was observed in OMC-1 and Sgr B2.[44] One year later, the 3+

0 − 2−

0 transition at 396272.412 MHz was observed in several regions, the clearest of which was the W3 IRS 5 cloud.[39]

The first far-IR 4−

3 − 3+

3 transition at 69.524 μm (4.3121 THz) was made in 1996 near Orion BN-IRc2.[45] In 2001, three additional transitions of H3O+ in were observed in the far infrared in Sgr B2; 2−

1 − 1+

1 transition at 100.577 μm (2.98073 THz), 1−

1 − 1+

1 at 181.054 μm (1.65582 THz) and 2−

0 − 1+

0 at 100.869 μm (2.9721 THz).[46]

See also

[edit]- Hydron (hydrogen cation)

- Hydride

- Hydrogen anion

- Hydrogen ion

- Grotthus mechanism

- Trifluorooxonium

- Law of dilution

References

[edit]- ^ Reed, C.A. (2013). "Myths about the proton. The nature of H+ in condensed media". Acc. Chem. Res. 46 (11): 2567–2575. doi:10.1021/ar400064q. PMC 3833890. PMID 23875729.

- ^ a b Silverstein, Todd P. (2014). "The aqueous proton is hydrated by more than one water molecule: Is the hydronium ion a useful conceit?". J. Chem. Educ. 91 (4): 608–610. Bibcode:2014JChEd..91..608S. doi:10.1021/ed400559t.

- ^ Thamer, M.; DeMarco, L.; Ramesha, K.; Mandel, A.; Tokmakoff, A. (2015). "Ultrafast 2D IR spectroscopy of the excess proton in liquid water". Science. 350 (6256): 78–82. Bibcode:2015Sci...350...78T. doi:10.1126/science.aab3908. PMID 26430117. S2CID 27074374.

- ^ Daly Jr., C.A.; Streacker, L.M.; Sun, Y.; Pattenaude, S.R.; Hassanali, A.A.; Petersen, P.B.; et al. (2017). "Decomposition of the experimental Raman and IR spectra of acidic water into proton, special pair, and counterion contributions". J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8 (21): 5246–5252. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.7b02435. PMID 28976760.

- ^ Dahms, F.; Fingerhut, B.P.; Nibbering, E.T.; Pines, E.; Elsaesser, T. (2017). "Large-amplitude transfer motion of hydrated excess protons mapped by ultrafast 2D IR spectroscopy". Science. 357 (6350): 491–495. Bibcode:2017Sci...357..491D. doi:10.1126/science.aan5144. PMID 28705988. S2CID 40492001.

- ^ Fournier, J.A.; Carpenter, W.B.; Lewis, N.H.; Tokmakoff, A. (2018). "Broadband 2D IR spectroscopy reveals dominant asymmetric H5O2+ proton hydration structures in acid solutions". Nature Chemistry. 10 (9): 932–937. Bibcode:2018NatCh..10..932F. doi:10.1038/s41557-018-0091-y. OSTI 1480907. PMID 30061612. S2CID 51882732.

- ^ "pH and Water". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "Table 17 Mononuclear parent onium ions". IUPAC.

- ^ Tang, Jian; Oka, Takeshi (1999). "Infrared spectroscopy of H3O+: the v1 fundamental band". Journal of Molecular Spectroscopy. 196 (1): 120–130. Bibcode:1999JMoSp.196..120T. doi:10.1006/jmsp.1999.7844. PMID 10361062.

- ^ Bell, R. P. (1973). The Proton in Chemistry (2nd ed.). Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 15.

- ^ Meister, Erich; Willeke, Martin; Angst, Werner; Togni, Antonio; Walde, Peter (2014). "Confusing Quantitative Descriptions of Brønsted-Lowry Acid-Base Equilibria in Chemistry Textbooks – A Critical Review and Clarifications for Chemical Educators". Helv. Chim. Acta. 97 (1): 1–31. doi:10.1002/hlca.201300321.

- ^ Silverstein, T.P.; Heller, S.T. (2017). "pKa Values in the Undergraduate Curriculum: What Is the Real pKa of Water?". J. Chem. Educ. 94 (6): 690–695. Bibcode:2017JChEd..94..690S. doi:10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00623.

- ^ Burgot, Jean-Louis (1998). "PerspectiveNew point of view on the meaning and on the values of Ka○(H3O+, H2O) and Kb○(H2O, OH−) pairs in water". The Analyst. 123 (2): 409–410. Bibcode:1998Ana...123..409B. doi:10.1039/a705491b.

- ^ Ballinger, P.; Long, F.A. (1960). "Acid Ionization Constants of Alcohols. II. Acidities of Some Substituted Methanols and Related Compounds". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 82 (4): 795–798. doi:10.1021/ja01489a008.

- ^ Silverstein, T.P. (2014). "The aqueous proton is hydrated by more than one water molecule: Is the hydronium ion a useful conceit?". J. Chem. Educ. 91 (4): 608–610. Bibcode:2014JChEd..91..608S. doi:10.1021/ed400559t.

- ^ "What is the pKa of Water". University of California, Davis. 2015-08-09. Archived from the original on 2016-02-14. Retrieved 2022-04-03.

- ^ Sorensen, S. P. L. (1909). "Ueber die Messung und die Bedeutung der Wasserstoffionenkonzentration bei enzymatischen Prozessen". Biochemische Zeitschrift (in German). 21: 131–304.

- ^ Zavitsas, A. A. (2001). "Properties of water solutions of electrolytes and nonelectrolytes". The Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 105 (32): 7805–7815. doi:10.1021/jp011053l.

- ^ Hulthe, G.; Stenhagen, G.; Wennerström, O.; Ottosson, C-H. (1997). "Water cluster studied by electrospray mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography A. 512: 155–165. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(97)00486-X.

- ^ Iyengar, S. S.; Petersen, M. K.; Burnham, C. J.; Day, T. J. F.; Voth, G. A.; Voth, G. A. (2005). "The Properties of Ion-Water Clusters. I. The Protonated 21-Water Cluster" (PDF). The Journal of Chemical Physics. 123 (8): 084309. Bibcode:2005JChPh.123h4309I. doi:10.1063/1.2007628. PMID 16164293.

- ^ Zundel, G.; Metzger, H. (1968). "Energiebänder der tunnelnden Überschuß-Protonen in flüssigen Säuren. Eine IR-spektroskopische Untersuchung der Natur der Gruppierungen H502+". Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 58 (5_6): 225–245. doi:10.1524/zpch.1968.58.5_6.225. S2CID 101048854.

- ^ Wicke, E.; Eigen, M.; Ackermann, Th (1954). "Über den Zustand des Protons (Hydroniumions) in wäßriger Lösung". Zeitschrift für Physikalische Chemie. 1 (5_6): 340–364. doi:10.1524/zpch.1954.1.5_6.340.

- ^ Marx, D.; Tuckerman, M. E.; Hutter, J.; Parrinello, M. (1999). "The nature of the hydrated excess proton in water". Nature. 397 (6720): 601–604. Bibcode:1999Natur.397..601M. doi:10.1038/17579. S2CID 204991299.

- ^ Mateescu, G. D.; Benedikt, G. M. (1979). "Water and related systems. 1. The hydronium ion (H3O+). Preparation and characterization by high resolution oxygen-17 nuclear magnetic resonance". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 101 (14): 3959–3960. doi:10.1021/ja00508a040.

- ^ Markovitch, O.; Agmon, N. (2007). "Structure and Energetics of the Hydronium Hydration Shells" (PDF). The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 111 (12): 2253–6. Bibcode:2007JPCA..111.2253M. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.76.9448. doi:10.1021/jp068960g. PMID 17388314. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-08-31. Retrieved 2018-08-30.

- ^ Stoyanov, Evgenii S.; Stoyanova, Irina V.; Reed, Christopher A. (January 15, 2010). "The Structure of the Hydrogen Ion (H+

aq) in Water". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 132 (5): 1484–1485. doi:10.1021/ja9101826. PMC 2946644. PMID 20078058. - ^ Stoyanov, Evgenii S.; Kim, Kee-Chan; Reed, Christopher A. (2006). "The Nature of the H3O+ Hydronium Ion in Benzene and Chlorinated Hydrocarbon Solvents. Conditions of Existence and Reinterpretation of Infrared Data". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (6): 1948–58. doi:10.1021/ja0551335. PMID 16464096. S2CID 33834275.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. doi:10.1016/C2009-0-30414-6. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ I. Taesler and I. Olavsson (1968). "Hydrogen bond studies. XXI. The crystal structure of sulfuric acid monohydrate." Acta Crystallogr. B24, 299-304. https://doi.org/10.1107/S056774086800227X

- ^ Faure, A.; Tennyson, J. (2003). "Rate coefficients for electron-impact rotational excitation of H3+ and H3O+". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 340 (2): 468–472. Bibcode:2003MNRAS.340..468F. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.2003.06306.x.

- ^ a b Hollis, J. M.; Churchwell, E. B.; Herbst, E.; De Lucia, F. C. (1986). "An interstellar line coincident with the P(2,l) transition of hydronium (H3O+)". Nature. 322 (6079): 524–526. Bibcode:1986Natur.322..524H. doi:10.1038/322524a0. S2CID 4346975.

- ^ a b Rauer, H (1997). "Ion composition and solar wind interaction: Observations of comet C/1995 O1 (Hale-Bopp)". Earth, Moon, and Planets. 79: 161–178. Bibcode:1997EM&P...79..161R. doi:10.1023/A:1006285300913. S2CID 119953549.

- ^ Vejby-Christensen, L.; Andersen, L. H.; Heber, O.; Kella, D.; Pedersen, H. B.; Schmidt, H. T.; Zajfman, D. (1997). "Complete Branching Ratios for the Dissociative Recombination of H2O+, H3O+, and CH3+". The Astrophysical Journal. 483 (1): 531–540. Bibcode:1997ApJ...483..531V. doi:10.1086/304242.

- ^ a b Neau, A.; Al Khalili, A.; Rosén, S.; Le Padellec, A.; Derkatch, A. M.; Shi, W.; Vikor, L.; Larsson, M.; Semaniak, J.; Thomas, R.; Någård, M. B.; Andersson, K.; Danared, H.; Af Ugglas, M. (2000). "Dissociative recombination of D3O+ and H3O+: Absolute cross sections and branching ratios". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 113 (5): 1762. Bibcode:2000JChPh.113.1762N. doi:10.1063/1.481979.

- ^ Neufeld, D. A.; Lepp, S.; Melnick, G. J. (1995). "Thermal Balance in Dense Molecular Clouds: Radiative Cooling Rates and Emission-Line Luminosities". The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 100: 132. Bibcode:1995ApJS..100..132N. doi:10.1086/192211.

- ^ a b c d Wootten, A.; Boulanger, F.; Bogey, M.; Combes, F.; Encrenaz, P. J.; Gerin, M.; Ziurys, L. (1986). "A search for interstellar H3O+". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 166: L15–8. Bibcode:1986A&A...166L..15W. PMID 11542067.

- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "heavy water". doi:10.1351/goldbook.H02758

- ^ Herbst, E.; Green, S.; Thaddeus, P.; Klemperer, W. (1977). "Indirect observation of unobservable interstellar molecules". The Astrophysical Journal. 215: 503–510. Bibcode:1977ApJ...215..503H. doi:10.1086/155381. hdl:2060/19770013020. S2CID 121202097.

- ^ a b Phillips, T. G.; Van Dishoeck, E. F.; Keene, J. (1992). "Interstellar H3O+ and its Relation to the O2 and H2O- Abundances" (PDF). The Astrophysical Journal. 399: 533. Bibcode:1992ApJ...399..533P. doi:10.1086/171945. hdl:1887/2260.

- ^ "H3O+ formation reactions". The UMIST Database for Astrochemistry.

- ^ "Dissociative recombination | physics". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2021-09-30.

- ^ Herbst, E.; Klemperer, W. (1973). "The formation and depletion of molecules in dense interstellar clouds". The Astrophysical Journal. 185: 505. Bibcode:1973ApJ...185..505H. doi:10.1086/152436.

- ^ Schwarz, H.A. (1977). "Gas phase infrared spectra of oxonium hydrate ions from 2 to 5 μm". Journal of Chemical Physics. 67 (12): 5525. Bibcode:1977JChPh..67.5525S. doi:10.1063/1.434748.

- ^ Wootten, A.; Turner, B. E.; Mangum, J. G.; Bogey, M.; Boulanger, F.; Combes, F.; Encrenaz, P. J.; Gerin, M. (1991). "Detection of interstellar H3O+ – A confirming line". The Astrophysical Journal. 380: L79. Bibcode:1991ApJ...380L..79W. doi:10.1086/186178.

- ^ Timmermann, R.; Nikola, T.; Poglitsch, A.; Geis, N.; Stacey, G. J.; Townes, C. H. (1996). "Possible discovery of the 70 μm {H3O+} 4−

3 − 3+

3 transition in Orion BN-IRc2". The Astrophysical Journal. 463 (2): L109. Bibcode:1996ApJ...463L.109T. doi:10.1086/310055. - ^ Goicoechea, J. R.; Cernicharo, J. (2001). "Far-infrared detection of H3O+ in Sagittarius B2". The Astrophysical Journal. 554 (2): L213. Bibcode:2001ApJ...554L.213G. doi:10.1086/321712. hdl:10261/192309.

External links

[edit]Hydronium

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition and Formation

The hydronium ion, denoted as , is the protonated form of a water molecule and represents the solvated hydrogen ion, , in aqueous solutions. It arises when a proton attaches to the oxygen atom of water, forming a cationic species that is central to acid-base chemistry in water.[6] The primary formation mechanism involves the protonation of water by a free hydrogen ion: .[7] This process occurs when acids dissociate in solution, transferring protons to water molecules. In pure water, hydronium ions also form through autoionization, where water molecules react with each other in equilibrium: . The equilibrium constant for this reaction is the ion product of water, at 25°C, indicating that both ions are present in very low concentrations in neutral water. The recognition of the hydronium ion traces back to Svante Arrhenius's 1884 theory of electrolytic dissociation, which posited that acids increase the concentration of hydrogen ions in aqueous solutions, later understood as .[8] This foundational idea was advanced in 1923 by the Brønsted-Lowry theory, which describes acids as proton donors that form hydronium ions by transferring to water as a base.[9] Beyond water, analogous protonated species form in other protic solvents; for instance, ammonia yields the ammonium ion upon protonation: .[10]Nomenclature

The hydronium ion, denoted as H₃O⁺, is systematically named oxidanium in accordance with IUPAC recommendations for inorganic nomenclature, with oxonium as an acceptable alternative; this reflects its status as a mononuclear parent hydride of oxygen with an added proton. The term "hydronium" is a commonly accepted specific descriptor for this ion in aqueous solution contexts, distinguishing it from broader oxonium species.[11] The nomenclature "oxonium ion" emphasizes the positive charge on the oxygen atom bearing three bonds, a convention rooted in the early 20th-century classification of onium ions. This term was notably introduced by Wendell M. Latimer and Worth H. Rodebush in their 1920 paper on polarity and ionization, where they described H₃O⁺ as an oxonium ion in the context of water's autoionization and hydrogen bonding. The alternative "hydronium" emerged around 1908 as a contraction of the German "Hydroxonium," highlighting the hydration of the proton.[12][13] In protonated water clusters, related species have distinct names: the H₅O₂⁺ ion is known as the Zundel cation, named after German chemist Georg Zundel for his work on delocalized protons in hydrogen bonds, while H₉O₄⁺ is the Eigen cation, honoring Nobel laureate Manfred Eigen's studies on proton solvation structures. These terms denote symmetric and asymmetric proton-sharing configurations, respectively. (Note: Using for name origins, as primary papers are cited indirectly; actual Zundel paper: https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/ja00345a001 for related work) In non-aqueous media, alkyl-substituted analogs follow substitutive nomenclature, such as trimethyloxonium for (CH₃)₃O⁺, a reactive cation used in methylation reactions and classified under onium ions. A common misconception involves confusing "hydronium" with the archaic or regional variant "hydroxonium," which is synonymous but less favored in modern American English; "protiated water" is an informal descriptor that overlooks the established ionic nomenclature.[1]Molecular Structure

The hydronium ion, , adopts a trigonal pyramidal geometry with point group symmetry in its isolated form. The three equivalent O-H bonds have a length of 0.974 Å, while the H-O-H bond angle measures 113.6°. This structure arises from the protonation of a water molecule, where the added proton occupies one of the tetrahedral positions around the central oxygen atom.[14] The bonding in involves the central oxygen atom, which is hybridized, forming three bonds with the hydrogen atoms using three of its four hybrid orbitals; the remaining orbital holds a lone pair of electrons. The three O-H bonds are equivalent due to resonance, with the positive charge delocalized symmetrically over the hydrogen atoms rather than residing solely on the oxygen. Quantum mechanically, this structure results from the interaction between the lone pair orbital on the oxygen atom of water (its highest occupied molecular orbital) and the empty $1s$ orbital of the incoming proton, leading to a strengthened bonding framework compared to neutral water, where the O-H bonds are slightly shorter (0.958 Å) but the H-O-H angle is smaller (104.5°).[14] Spectroscopically, the isolated ion exhibits characteristic infrared vibrational modes reflective of its symmetry. The symmetric O-H stretch (, symmetry) appears at approximately 3390 cm, while the asymmetric O-H stretch (, symmetry) is observed near 3491 cm. The degenerate bending mode (, symmetry) occurs around 1630 cm, and the inversion mode (, symmetry) is at about 950 cm. These frequencies, derived from high-resolution gas-phase spectroscopy, confirm the pyramidal structure and provide insight into the ion's electronic distribution.[14]Aqueous Chemistry

Relation to pH

The pH of an aqueous solution is defined as the negative base-10 logarithm of the hydronium ion activity, expressed as pH = −log₁₀ a(H₃O⁺), where a(H₃O⁺) approximates the concentration [H₃O⁺] in dilute solutions.[15] This scale was introduced by Danish biochemist Søren Peder Lauritz Sørensen in 1909 as a practical measure of hydrogen ion concentration in biochemical processes.[16] In typical aqueous solutions at 25°C, the pH scale ranges from 0 to 14, with acidic solutions having pH < 7, basic solutions pH > 7, and neutral solutions at pH = 7, where [H₃O⁺] = [OH⁻] = 10⁻⁷ M, corresponding to the ion product of water K_w = 1.0 × 10⁻¹⁴.[17] This neutral point arises from the autoionization of water: 2 H₂O ⇌ H₃O⁺ + OH⁻, with K_w = [H₃O⁺][OH⁻]./03%3A_The_First_Law/3.05%3A_The_Ionic_Product_of_Water) pH calculations for strong acids assume complete dissociation; for example, in a 1 M HCl solution, HCl → H₃O⁺ + Cl⁻ yields [H₃O⁺] ≈ 1 M, so pH ≈ 0.[18] For weak acids, the hydronium concentration is estimated using the acid dissociation constant K_a via the equilibrium HA + H₂O ⇌ H₃O⁺ + A⁻, where [H₃O⁺] ≈ √(K_a × [HA]_initial) for dilute solutions; for 0.1 M acetic acid (CH₃COOH, K_a = 1.8 × 10⁻⁵), [H₃O⁺] ≈ 1.3 × 10⁻³ M, yielding pH ≈ 2.9.[19] The value of K_w increases with temperature due to the endothermic nature of water autoionization, shifting the neutral pH below 7; at 100°C, K_w ≈ 5.5 × 10⁻¹³, so neutral pH ≈ 6.14.[20] pH is measured using pH meters, which employ a glass electrode sensitive to hydronium ion activity, paired with a reference electrode to generate a potential difference proportional to pH via the Nernst equation.[21]Acidity and Proton Transfer

In the Brønsted-Lowry theory of acid-base reactions, acids are defined as proton (H⁺) donors and bases as proton acceptors, with the hydronium ion (H₃O⁺) serving as the primary species representing the proton in aqueous solutions.[22] H₃O⁺ acts as the strongest conceivable acid in water because any stronger acid will transfer its proton to H₂O, forming H₃O⁺ and the conjugate base of the original acid.[23] This positions H₃O⁺ at the top of the acid strength hierarchy in aqueous media, where it readily donates a proton to any available base stronger than H₂O.[24] The acidity of H₃O⁺ is quantified by its acid dissociation constant, with pK_a = -1.74 at 25°C for the reaction H₃O⁺ ⇌ H⁺ + H₂O (using [H₂O] ≈ 55.5 M). This indicates H₃O⁺ is a strong acid, but in aqueous solution, it represents the leveled strength of all stronger acids, as they fully protonate water, and H₃O⁺ cannot persist as a distinct species beyond this form due to the solvent's properties.[25] This underscores why water levels the strengths of all acids to that of H₃O⁺, preventing the observation of intrinsic acidities beyond this limit.[26] A key consequence of this is the leveling effect observed for strong acids in aqueous solutions, where acids stronger than H₃O⁺, such as HCl, fully protonate water to produce H₃O⁺ and Cl⁻, rendering their strengths indistinguishable from one another.[24] For instance, HCl dissociates completely as HCl + H₂O → H₃O⁺ + Cl⁻, with the reaction equilibrium lying far to the right due to the high basicity of H₂O relative to Cl⁻.[27] This effect masks differences in acid strength for perchloric acid (HClO₄), hydroiodic acid (HI), and others, all of which behave equivalently as H₃O⁺ donors in water.[28] Proton transfer involving H₃O⁺ in water occurs via the Grotthuss mechanism, a chain-like hopping process through the hydrogen-bonded network of water molecules, rather than direct diffusion of the intact H₃O⁺ ion.[29] In this mechanism, the excess proton rapidly transfers from one oxygen atom to a neighboring one via hydrogen bond rearrangement, with individual hopping events occurring on a timescale of approximately 10⁻¹² seconds (1 picosecond).[30] This enables anomalously high proton mobility in aqueous solutions, far exceeding that of other ions. A representative example is the reaction H₃O⁺ + NH₃ → NH₄⁺ + H₂O, where H₃O⁺ donates its proton to ammonia, a stronger base than water, proceeding efficiently through the Grotthuss pathway.[31]Solvation in Liquids

In liquid solvents, the hydronium ion () is stabilized through solvation, where surrounding solvent molecules form a hydration shell that delocalizes the positive charge via hydrogen bonding. In water, the first solvation shell typically consists of three water molecules that accept hydrogen bonds from the central , effectively distributing the charge over the complex and reducing the effective charge density on the core ion. This asymmetric solvation structure arises from the pyramidal geometry of , with the three coordinating waters oriented to accept bonds from the ion's hydrogens, while the fourth position remains open for further interactions in the dynamic liquid environment.[32] The hydrated proton in water exhibits structural motifs that interconvert dynamically, primarily between the Eigen and Zundel cations. The Eigen cation () features a symmetric core solvated by three water molecules in the first shell, with an additional water completing the tetra-coordination in a second shell, leading to a localized charge distribution.[33] In contrast, the Zundel cation () involves a shared proton between two water molecules forming a symmetric core, flanked by four additional waters, resulting in greater delocalization of the charge.[34] These forms represent transient states in the proton's diffusion pathway, with simulations showing rapid interconversion on picosecond timescales, influenced by the local hydrogen-bond network.[35] The high dielectric permittivity of water ( at 25°C) plays a crucial role in screening the charge of the solvated , mitigating electrostatic interactions and enabling higher ion mobility compared to lower-permittivity solvents.[36] This screening effect reduces the Coulombic barriers for proton hopping, allowing the hydronium ion to navigate the solvent with enhanced freedom, as evidenced by dielectric relaxation studies that highlight water's ability to reorganize dipoles around charged species.[37] The transport properties of in water are anomalous due to structural diffusion via the Grotthuss mechanism, where the excess proton hops through hydrogen-bonded chains rather than physical displacement of the entire ion. This results in a high diffusion coefficient of approximately at 25°C, significantly faster than typical monatomic ions like Na ().[38] The mechanism involves sequential proton transfers between hydronium and water, facilitated by the Eigen-to-Zundel transitions, leading to superdiffusive behavior on short timescales.[39] In non-aqueous solvents, hydronium analogs exhibit analogous solvation but adapted to the solvent's chemistry. In liquid ammonia, the proton forms the ammonium ion (), solvated by three ammonia molecules in the first shell via hydrogen bonds, similar to water's hydration but with weaker bonding due to ammonia's lower polarity.[40] In anhydrous sulfuric acid, the proton is solvated as , where a sulfuric acid molecule donates to the proton, forming a structure with delocalized charge over the sulfur-oxygen framework, contributing to the medium's superacidic properties through low solvation energy barriers.[41] These analogs highlight how solvent basicity and hydrogen-bonding capacity dictate proton stabilization across protic media.[42]Condensed Phases

Solid Hydronium Salts

Solid hydronium salts, also known as acid monohydrates, form with strong acids with high ionization constants, such as HCl (Ka ≈ 10^7) and perchloric acid (Ka > 10^9), allowing the isolation of H₃O⁺ as a discrete cation paired with weakly coordinating anions. Common examples include hydronium chloride (H₃O⁺ Cl⁻, from HCl monohydrate), hydronium tetrafluoroborate (H₃O⁺ BF₄⁻), and hydronium perchlorate (H₃O⁺ ClO₄⁻). These compounds exhibit ionic character in the solid state, with the hydronium cation stabilized by hydrogen bonding to the anion or lattice water molecules, distinguishing them from dynamic solvated species in liquids.[43] Synthesis of these salts generally involves low-temperature crystallization from aqueous solutions of the parent strong acids, where stoichiometric water is added to concentrated acid to promote precipitation below the compound's stability limit. For instance, single crystals of HCl monohydrate are obtained by repeated freezing and melting cycles of an equimolar HCl-water mixture at around 258 K, yielding a disordered ionic structure of H₃O⁺ and Cl⁻ ions. Similarly, hydronium perchlorate forms by cooling a stoichiometric mixture of perchloric acid and water to below -30 °C, resulting in a low-temperature phase with ordered hydrogen bonding. Hydronium tetrafluoroborate is prepared from fluoroboric acid solutions, often stabilized in complexes for handling. These methods exploit the acids' high proton affinity to form the H₃O⁺ cation while minimizing decomposition.[44][45] The thermal stability of solid hydronium salts is limited by the high mobility of the proton within the H₃O⁺ cation, leading to deprotonation, phase transitions, or decomposition into the anhydrous acid and water at mild temperatures. Many such salts are stable only below -40 °C; for example, hydronium perchlorate undergoes a first-order phase transition at 248.4 K (-24.6 °C) and decomposes above -30 °C due to proton hopping in the lattice. HCl monohydrate exhibits instability above its melting point of 258 K, reverting to gaseous HCl and ice through proton transfer. This fragility arises from the weak binding of the third proton in H₃O⁺, facilitating facile proton exchange.[46][44] Spectroscopic techniques provide key identification of the H₃O⁺ cation in these solids, with Raman and FTIR revealing characteristic vibrational modes shifted from free water due to the asymmetric environment. The degenerate bending mode (ν₄(E)) of H₃O⁺ appears as a prominent band near 1700–1740 cm⁻¹, reflecting the pyramidal C₃ᵥ symmetry and hydrogen bonding perturbations. For hydronium perchlorate, additional modes include symmetric stretching (ν₁(A₁)) around 2800 cm⁻¹ and asymmetric stretching (ν₃(E)) near 2500 cm⁻¹, confirming the ion's presence amid anion vibrations. These signatures enable unambiguous detection in complex matrices.[47][43] In applications, solid hydronium salts serve as precursors for generating anhydrous strong acids through controlled thermal decomposition, where heating expels water to yield pure HCl or HClO₄ vapors. They also play a role in superacid chemistry, where stabilized H₃O⁺ variants in weakly coordinating media enable studies of protonated intermediates and high-acidity reactions, such as in carborane-based systems. These uses leverage the salts' ability to deliver concentrated proton activity without solvent interference.[48][49]Crystal Structures and Properties

The crystal structures of solid hydronium phases often feature orthorhombic lattices, as exemplified by the polar orthorhombic arrangement with space group Iba2 in salts like [H₃O][NbF₆], where the hydronium ion integrates into an extended framework of anions and water molecules.[50] In the case of hydronium chloride (HCl monohydrate), the structure comprises ferroelectric domains of H₃O⁺ and Cl⁻ ions, forming layered configurations where each hydronium ion interacts closely with three chloride ions, leading to a non-centrosymmetric arrangement confirmed by X-ray diffraction and spectroscopic data.[51] These lattices reflect the ionic nature of the H₃O⁺ cation, with tetrahedral-like coordination environments around the central oxygen, though distorted by anion interactions. Hydrogen bonding networks in hydronium crystals are predominantly asymmetric, with H₃O⁺...H₂O interactions exhibiting varied bond lengths and angles that deviate from the isotropic hydrogen bonds in aqueous solutions. For instance, in [H₃O][NbF₆], the O-H distances range from 0.69 to 0.76 Å, significantly shorter than typical water-water bonds (0.986–1.020 Å), forming charge-assisted networks that stabilize the crystal through cyclic and sheet-like motifs involving multiple water and anion units.[50] These asymmetric bonds facilitate directional proton transfers and contribute to the overall cohesion of the solid phase, often resulting in quasi-planar or acyclic hydronium aggregates beyond the simple H₃O⁺ unit. Phase transitions in hydronium-incorporating systems occur under high-pressure conditions, such as in doped ice phases where H₃O⁺ substitutes for water molecules in ice VI, leading to proton ordering transitions around 120–130 K and shifts in dielectric properties due to enhanced hydrogen bond symmetrization.[52] This incorporation alters the phase diagram of high-pressure ices, promoting solid-solid transitions that involve reorientation of hydrogen bonds within the body-centered tetragonal framework of ice VI.[53] Electrical properties of hydronium perchlorate clathrates demonstrate significant protonic conductivity, reaching approximately 10^{-2} S/cm at around 220 K through Grotthuss-like mechanisms involving delocalized excess protons along cage-like substructures.[54] In hydronium perchlorate clathrates, this conductivity arises from rapid proton hopping between H₃O⁺ sites and surrounding water networks, enhanced by the rotational dynamics of the perchlorate anions.[54] Theoretical modeling of these structures employs density functional theory (DFT) to compute lattice energies, revealing stabilization energies dominated by electrostatic and hydrogen bonding contributions in hydronium salts, with methods like CE-B3LYP providing accurate estimates within 5–10 kJ/mol of experimental benchmarks for similar ionic molecular crystals.[55] Such calculations highlight the role of dispersion corrections in predicting the energetic preference for orthorhombic over cubic lattices in certain hydronium systems.[50]Astrophysical Contexts

Interstellar Formation and Chemistry

In interstellar environments, the hydronium ion (H₃O⁺) forms primarily through gas-phase ion-molecule reactions initiated by cosmic ray ionization. The dominant pathway is the exothermic proton transfer between the protium trimer ion and water:This reaction proceeds at near-collision rates and is particularly prevalent in diffuse clouds, where H₃⁺ abundances are maintained by the ionization of H₂, followed by rapid reactions with atomic or molecular species. Laboratory simulations using ion trap apparatuses at low temperatures (∼10–50 K) have measured the rate constant for this process as cm³ s⁻¹, confirming its efficiency under interstellar conditions.[56][57] Subsequent destruction of H₃O⁺ occurs mainly via dissociative recombination with free electrons:

or

with branching ratios favoring OH production (∼60–70%) at low temperatures, leading to hydroxyl radicals and atomic hydrogen. These recombination channels, with rate coefficients on the order of 10^{-7} cm³ s⁻¹, close the cycle of oxygen-bearing ion chemistry in the gas phase.[56][57] Astrophysical models of cold molecular clouds (T ≈ 10 K) predict H₃O⁺ abundances relative to total hydrogen nuclei of ∼10^{-8}, yielding a ratio [H₃O⁺]/[H₂O] ≈ 10^{-8} in the gas phase, where water is partially depleted onto dust grains. These ratios arise from steady-state photodissociation region simulations balancing production from H₃⁺ with recombination and freeze-out.[58] As a central node in interstellar oxygen chemistry, H₃O⁺ acts as a precursor to OH radicals, which drive the formation of water (H₂O) and its eventual accretion onto grain mantles as ice, accounting for much of the cosmic oxygen reservoir in dense regions. This role underscores H₃O⁺'s importance in bridging gas-phase ion reactions to solid-state chemistry.[58]