Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Isoelectronicity

View on WikipediaIsoelectronicity is a phenomenon observed when two or more molecules have the same structure (positions and connectivities among atoms) and the same electronic configurations, but differ by what specific elements are at certain locations in the structure. For example, CO, NO+

, and N

2 are isoelectronic, while CH

3COCH

3 and CH3N=NCH3 are not.[1]

This definition is sometimes termed valence isoelectronicity. Definitions can sometimes be not as strict, sometimes requiring identity of the total electron count and with it the entire electronic configuration.[2] More usually, definitions are broader, and may extend to allowing different numbers of atoms in the species being compared.[3]

The importance of the concept lies in identifying significantly related species, as pairs or series. Isoelectronic species can be expected to show useful consistency and predictability in their properties, so identifying a compound as isoelectronic with one already characterised offers clues to possible properties and reactions. Differences in properties such as electronegativity of the atoms in isolelectronic species can affect reactivity.

In quantum mechanics, hydrogen-like atoms are ions with only one electron such as Li2+

. These ions would be described as being isoelectronic with hydrogen.

Examples

[edit]The N atom and the O+

ion are isoelectronic because each has five valence electrons, or more accurately an electronic configuration of [He] 2s2 2p3.

Similarly, the cations K+

, Ca2+

, and Sc3+

and the anions Cl−

, S2−

, and P3−

are all isoelectronic with the Ar atom.

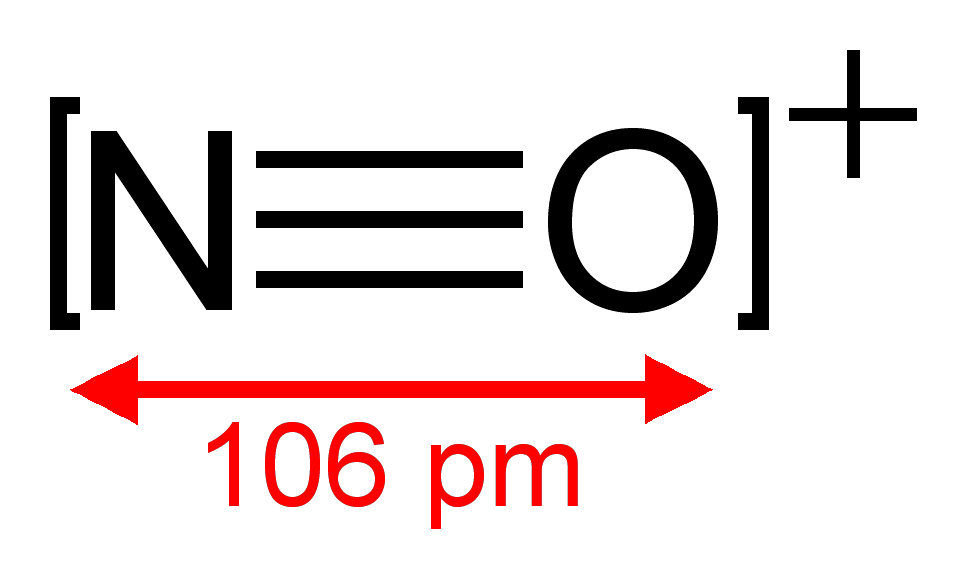

CO, CN−

, N

2, and NO+

are isoelectronic because each has two atoms triple bonded together, and due to the charge have analogous electronic configurations (N−

is identical in electronic configuration to O so CO is identical electronically to CN−

).

Molecular orbital diagrams best illustrate isoelectronicity in diatomic molecules, showing how atomic orbital mixing in isoelectronic species results in identical orbital combination, and thus also bonding.

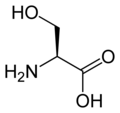

More complex molecules can be isoelectronic also. For example, the amino acids serine, cysteine, and selenocysteine are all valence isoelectronic to each other. They differ by which specific chalcogen is present at one location in the side-chain.

CH

3COCH

3 (acetone) and CH

3N

2CH

3 (azomethane) are not isoelectronic. They do have the same number of electrons but they do not have the same structure.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 5th ed. (the "Gold Book") (2025). Online version: (2006–) "isoelectronic". doi:10.1351/goldbook.I03276

- ^ Isoelectronic Configurations Archived 2017-07-17 at the Wayback Machine iun.edu

- ^ A. A. Aradi & T. P. Fehlner, "Isoelectronic Organometallic Molecules", in F. G. A. Stone & Robert West (eds.) Advances in Organometallic Chemistry Vol. 30 (1990), Chapter 5 (at p. 190) google books link

Isoelectronicity

View on GrokipediaFundamentals

Definition

Isoelectronic species are atoms, ions, or molecules that possess the same total number of electrons, leading to analogous electron configurations despite differences in their atomic numbers and nuclear charges.[1] This equivalence in electron count allows for structural and behavioral similarities, as the electrons occupy equivalent orbitals and energy levels, though the varying nuclear charges influence the spatial distribution of these electrons.[5] The term "isoelectronic" was first introduced in 1926 by Arthur A. Blanchard in the context of organometallic chemistry. It later gained usage in molecular spectroscopy in the 1930s, where it was employed as a synonym for "isosteric" in a 1935 monograph by R. de L. Kronig, and achieved prominence through its application in chemical bonding theory by Linus Pauling.[6] Pauling employed the concept extensively in his seminal 1939 work, The Nature of the Chemical Bond and the Structure of Polyatomic Molecules, to explain parallels in molecular geometries and bond characteristics among species with identical electron counts, such as certain metal carbonyl complexes and ionic crystals.[7] At its core, isoelectronicity manifests in sequences where the electron number remains fixed while the number of protons (atomic number) increases progressively across elements or ions. This progression results in a rising effective nuclear charge, as additional protons enhance the attraction on the shared electron cloud without a corresponding increase in shielding, thereby contracting the overall size and altering properties like reactivity.[8] Such sequences underscore the periodic nature of electronic structures, providing a framework for predicting chemical analogies independent of specific elemental identities.[9]Electron Configuration Basis

Isoelectronic species are characterized by having the same number of electrons arranged in identical quantum mechanical orbitals, forming the foundational basis for their shared electronic structure. This is expressed through electron configuration notation, which describes the distribution of electrons into subshells following the order of increasing energy levels. For instance, species with a neon-like configuration, such as the neutral neon atom (Ne), fluoride anion (F⁻), sodium cation (Na⁺), and magnesium dication (Mg²⁺), all exhibit the ground-state arrangement , accommodating ten electrons in the same orbital pattern.[10][11] The uniformity in these configurations arises from the application of the Aufbau principle, which dictates that electrons fill atomic orbitals starting from the lowest energy state and proceeding to higher ones, adhering to the Pauli exclusion principle and Hund's rule for maximum stability. In isoelectronic sets, this principle ensures that electrons occupy the same subshells and spin arrangements regardless of the differing atomic numbers of the species involved, thereby conferring similar chemical behaviors and reactivity patterns. For example, the sequential filling of the 1s, 2s, and 2p orbitals in neon-like species results in a closed-shell noble gas configuration that is energetically favorable and inert.[12][13] A key quantum mechanical factor influencing these configurations is the effective nuclear charge (), which represents the net positive charge felt by valence electrons after accounting for shielding by inner electrons. It is approximated by the formula where is the atomic number (nuclear charge) and is the screening constant derived from the electron cloud's shielding effect. In isoelectronic species, the identical electron arrangement keeps relatively constant, so an increase in directly raises , intensifying the attraction on the shared electrons and altering orbital sizes without changing the configuration itself. This framework, originating from Slater's shielding model, underscores why isoelectronic ions with higher exhibit more compact electron distributions while retaining the same overall electronic architecture.[14]Properties

Atomic and Ionic Sizes

In isoelectronic species, which share the same electron configuration such as the neon-like [Ne] (1s² 2s² 2p⁶), atomic and ionic radii decrease systematically with increasing atomic number (Z) due to the progressively stronger nuclear attraction on the identical electron cloud.[1] For instance, in the neon isoelectronic series, the ionic radius of O²⁻ (Z=8) is larger than that of F⁻ (Z=9), which in turn exceeds Na⁺ (Z=11) and Mg²⁺ (Z=12). This trend is also evident in the argon isoelectronic series with 18 electrons ([Ar] configuration: 1s² 2s² 2p⁶ 3s² 3p⁶), where ionic radii decrease with increasing nuclear charge in the sequence Cl⁻ (Z=17), K⁺ (Z=19), Ca²⁺ (Z=20), Sc³⁺ (Z=21). This trend is quantified through effective ionic radii derived from crystallographic data, as shown in the table below for representative species in the series (values in picometers, pm, for coordination number VI where applicable).| Species | Ionic Radius (pm) | Z |

|---|---|---|

| O²⁻ | 140 | 8 |

| F⁻ | 133 | 9 |

| Na⁺ | 102 | 11 |

| Mg²⁺ | 72 | 12 |