Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Index notation

View on WikipediaIn mathematics and computer programming, index notation is used to specify the elements of an array of numbers. The formalism of how indices are used varies according to the subject. In particular, there are different methods for referring to the elements of a list, a vector, or a matrix, depending on whether one is writing a formal mathematical paper for publication, or when one is writing a computer program.

In mathematics

[edit]It is frequently helpful in mathematics to refer to the elements of an array using subscripts. The subscripts can be integers or variables. The array takes the form of tensors in general, since these can be treated as multi-dimensional arrays. Special (and more familiar) cases are vectors (1d arrays) and matrices (2d arrays).

The following is only an introduction to the concept: index notation is used in more detail in mathematics (particularly in the representation and manipulation of tensor operations). See the main article for further details.

One-dimensional arrays (vectors)

[edit]A vector treated as an array of numbers by writing as a row vector or column vector (whichever is used depends on convenience or context):

Index notation allows indication of the elements of the array by simply writing ai, where the index i is known to run from 1 to n, because of n-dimensions.[1] For example, given the vector:

then some entries are

- .

The notation can be applied to vectors in mathematics and physics. The following vector equation

can also be written in terms of the elements of the vector (aka components), that is

where the indices take a given range of values. This expression represents a set of equations, one for each index. If the vectors each have n elements, meaning i = 1,2,…n, then the equations are explicitly

Hence, index notation serves as an efficient shorthand for

- representing the general structure to an equation,

- while applicable to individual components.

Two-dimensional arrays

[edit]

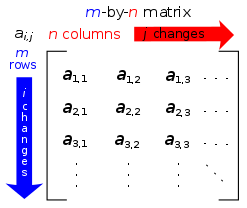

More than one index is used to describe arrays of numbers, in two or more dimensions, such as the elements of a matrix, (see also image to right);

The entry of a matrix A is written using two indices, say i and j, with or without commas to separate the indices: aij or ai,j, where the first subscript is the row number and the second is the column number. Juxtaposition is also used as notation for multiplication; this may be a source of confusion. For example, if

then some entries are

- .

For indices larger than 9, the comma-based notation may be preferable (e.g., a3,12 instead of a312).

Matrix equations are written similarly to vector equations, such as

in terms of the elements of the matrices (aka components)

for all values of i and j. Again this expression represents a set of equations, one for each index. If the matrices each have m rows and n columns, meaning i = 1, 2, …, m and j = 1, 2, …, n, then there are mn equations.

Multi-dimensional arrays

[edit]The notation allows a clear generalization to multi-dimensional arrays of elements: tensors. For example,

representing a set of many equations.

In tensor analysis, superscripts are used instead of subscripts to distinguish covariant from contravariant entities, see covariance and contravariance of vectors and raising and lowering indices.

In computing

[edit]In several programming languages, index notation is a way of addressing elements of an array. This method is used since it is closest to how it is implemented in assembly language whereby the address of the first element is used as a base, and a multiple (the index) of the element size is used to address inside the array.

For example, if an array of integers is stored in a region of the computer's memory starting at the memory cell with address 3000 (the base address), and each integer occupies four cells (bytes), then the elements of this array are at memory locations 0x3000, 0x3004, 0x3008, …, 0x3000 + 4(n − 1) (note the zero-based numbering). In general, the address of the ith element of an array with base address b and element size s is b + is.

Implementation details

[edit]In the C programming language, we can write the above as *(base + i) (pointer form) or base[i] (array indexing form), which is exactly equivalent because the C standard defines the array indexing form as a transformation to pointer form. Coincidentally, since pointer addition is commutative, this allows for obscure expressions such as 3[base] which is equivalent to base[3].[2]

Multidimensional arrays

[edit]Things become more interesting when we consider arrays with more than one index, for example, a two-dimensional table. We have three possibilities:

- make the two-dimensional array one-dimensional by computing a single index from the two

- consider a one-dimensional array where each element is another one-dimensional array, i.e. an array of arrays

- use additional storage to hold the array of addresses of each row of the original array, and store the rows of the original array as separate one-dimensional arrays

In C, all three methods can be used. When the first method is used, the programmer decides how the elements of the array are laid out in the computer's memory, and provides the formulas to compute the location of each element. The second method is used when the number of elements in each row is the same and known at the time the program is written. The programmer declares the array to have, say, three columns by writing e.g. elementtype tablename[][3];. One then refers to a particular element of the array by writing tablename[first index][second index]. The compiler computes the total number of memory cells occupied by each row, uses the first index to find the address of the desired row, and then uses the second index to find the address of the desired element in the row. When the third method is used, the programmer declares the table to be an array of pointers, like in elementtype *tablename[];. When the programmer subsequently specifies a particular element tablename[first index][second index], the compiler generates instructions to look up the address of the row specified by the first index, and use this address as the base when computing the address of the element specified by the second index.

void mult3x3f(float result[][3], const float A[][3], const float B[][3])

{

int i, j, k;

for (i = 0; i < 3; ++i) {

for (j = 0; j < 3; ++j) {

result[i][j] = 0;

for (k = 0; k < 3; ++k)

result[i][j] += A[i][k] * B[k][j];

}

}

}

In other languages

[edit]In other programming languages such as Pascal, indices may start at 1, so indexing in a block of memory can be changed to fit a start-at-1 addressing scheme by a simple linear transformation – in this scheme, the memory location of the ith element with base address b and element size s is b + (i − 1)s.

References

[edit]- ^ An introduction to Tensor Analysis: For Engineers and Applied Scientists, J.R. Tyldesley, Longman, 1975, ISBN 0-582-44355-5

- ^ Programming with C++, J. Hubbard, Schaum's Outlines, McGraw Hill (USA), 1996, ISBN 0-07-114328-9

- Programming with C++, J. Hubbard, Schaum's Outlines, McGraw Hill (USA), 1996, ISBN 0-07-114328-9

- Tensor Calculus, D.C. Kay, Schaum's Outlines, McGraw Hill (USA), 1988, ISBN 0-07-033484-6

- Mathematical methods for physics and engineering, K.F. Riley, M.P. Hobson, S.J. Bence, Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-86153-3

Index notation

View on GrokipediaIn Mathematics

Vectors and One-Dimensional Arrays

In index notation, one-dimensional arrays, commonly referred to as vectors in linear algebra, are represented as ordered sequences of scalar components denoted by a lowercase letter with a single subscript, such as , where the index specifies the position and ranges from 1 to , the dimension of the vector.[1] This notation treats the vector as a list of numbers, allowing precise reference to individual elements without explicit coordinate systems beyond the indexing.[4] For instance, consider the vector , which has dimension ; its components are then , , , , , and . Such representation facilitates the handling of vectors as arrays in algebraic manipulations. Basic operations on vectors using index notation emphasize component-wise actions. Element-wise addition of two vectors and to form is expressed as for each to , yielding independent scalar equations that collectively define the resulting vector.[1] Similarly, scalar multiplication follows .[4] In mathematical contexts, the index range conventionally begins at 1, aligning with the natural numbering of positions in sequences, though adjustments may occur in specific applications.[1] Summation over indices is not implied in this basic form and requires explicit indication, distinguishing it from more advanced conventions.[4] The subscript notation for vectors emerged in 19th-century linear algebra texts to denote coordinate representations, with early systematic use appearing in Hermann Grassmann's Die lineale Ausdehnungslehre (1844), which employed indices for vector components in higher-dimensional extensions.[5] This approach was further developed by J. Willard Gibbs in his vector analysis notes around 1881–1884, solidifying its role in coordinate-based algebra.[5]Matrices and Two-Dimensional Arrays

In mathematics, matrices are defined as rectangular arrays of numbers arranged in rows and columns, represented using double-index notation with two subscripts , where denotes the row index ranging from 1 to (the number of rows) and denotes the column index ranging from 1 to (the number of columns).[6][1] This structure allows precise access to individual elements, such as the entry in the -th row and -th column.[1] Matrices are typically denoted by uppercase letters in boldface, such as , to distinguish them from scalars and vectors, which use italicized lowercase letters or bold lowercase for vectors with a single index.[7] Building on vector notation, a matrix can be viewed as an array of row vectors, where the -th row is itself a vector .[6] For example, consider the matrix where is the element in the first row and first column, and is the element in the second row and third column. The double-subscript notation for matrices has roots in early 19th-century work on determinants and linear systems, with Augustin-Louis Cauchy using as early as 1812. It was systematized by Arthur Cayley in his 1858 memoir on the theory of matrices, establishing matrices as algebraic objects with indexed components.[8] A fundamental operation on matrices is element-wise addition, applicable to two matrices and of the same dimensions . The resulting matrix has entries given by for all and , producing independent equations that define the sum.[6] This operation preserves the rectangular structure and is both commutative and associative, mirroring scalar addition.[6]Tensors and Higher-Dimensional Arrays

In index notation, tensors extend the concepts of vectors and matrices to multi-dimensional arrays that require multiple indices to specify their components. A tensor of order (also referred to as rank ) is formally defined as a multidimensional or -way array, where , with elements accessed via indices , each ranging from 1 to the size of the corresponding dimension (rank-0 for scalars, rank-1 for vectors, rank-2 for matrices, and higher for more complex structures).[9] This notation allows tensors to represent data with more than two dimensions, capturing relationships in multi-way structures such as those arising in scientific computing and physical modeling.[10] The order or rank of a tensor indicates the number of indices needed to identify a unique component, distinguishing it from lower-order objects: rank-1 tensors correspond to vectors (one index), rank-2 to matrices (two indices), and higher ranks to more complex multi-way data arrays. For instance, a rank-3 tensor in three-dimensional space has components, with each index typically running from 1 to 3. Components of tensors are conventionally denoted using lowercase letters with multiple subscripts placed below the symbol, such as , where the absence of repeated indices implies no summation is performed.[10] The multi-index notation for tensors was developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as part of absolute differential calculus, primarily by Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro in works from the 1880s to 1900, with refinements by Tullio Levi-Civita, enabling the compact handling of multilinear forms in geometry and physics. Basic operations on tensors, such as addition, are performed component-wise across matching indices. For a rank-3 tensor addition, if and are tensors with dimensions , the resulting tensor has components given by where to , to , and to . This preserves the multi-dimensional structure without altering the index ranges.[10] Tensors find applications in continuum mechanics, where higher-order tensors describe complex physical phenomena, such as the stress tensor that quantifies internal forces within materials, though the standard stress tensor is rank-2; extensions to higher ranks appear in advanced models of material behavior.[11]Advanced Mathematical Applications

Einstein Summation Convention

The Einstein summation convention, also known as Einstein notation, is a notational shorthand in tensor algebra where a repeated index in a mathematical expression implies an implicit summation over that index, eliminating the need for explicit summation symbols.[12] Specifically, when an index appears exactly twice in a term—typically once as a subscript (lower position) and once as a superscript (upper position) in contexts involving metrics, or both as subscripts in Euclidean spaces—the expression denotes a sum over all possible values of that index, ranging from 1 to the dimension of the space.[13] For instance, the scalar product of two vectors and in three dimensions is written as , where the repeated index indicates the summation without the explicit symbol.[14] This convention was introduced by Albert Einstein in his 1916 paper "Die Grundlage der allgemeinen Relativitätstheorie," where it served to streamline the complex tensor equations of general relativity by suppressing summation signs and reducing notational clutter.[15] Einstein employed it to handle the multi-index contractions essential for describing spacetime curvature, marking a significant simplification over earlier explicit summation methods used in tensor calculus.[16] The rules of the convention are precise to ensure unambiguous interpretation: exactly one pair of repeated indices per term triggers the summation, and no more than two occurrences of the same index are allowed in a single term to avoid confusion; indices that appear only once in an expression are termed "free indices" and determine the rank (or tensor order) of the resulting object.[12] For example, in the expression for the -th component of a vector cross product or higher operations, free indices like or remain unsummed, while dummies (repeated ones) are contracted.[13] Violation of these rules, such as triple repetition, requires explicit clarification or reformulation. Illustrative examples highlight its application. The dot product of vectors and is compactly expressed as , where the metric raises one index, implying summation over .[14] For matrix multiplication, the -component of the product matrix is , with summation over the repeated index (from 1 to the matrix dimension), transforming what would be a verbose triple loop into a single concise equation.[16] The primary advantages of the Einstein summation convention lie in its ability to reduce the verbosity of tensor equations, making them more readable and less prone to notational errors in fields like physics and differential geometry, where multi-index manipulations are routine.[13] By implicitly handling contractions, it facilitates quicker derivations and pattern recognition in covariant formulations, as seen in relativity and continuum mechanics, without altering the underlying mathematics.[12]Covariant and Contravariant Indices

In tensor notation, indices are distinguished as covariant or contravariant based on their transformation properties under changes of coordinates. Covariant indices, denoted by subscripts (e.g., ), transform in the same manner as the coordinate basis vectors, following the rule .[17] Contravariant indices, denoted by superscripts (e.g., ), transform inversely to the basis, as .[17] For a covector, such as the differential form , the components carry a lower index and transform covariantly, while a position vector has contravariant components with an upper index.[18] Tensors of higher rank incorporate both types of indices, with the total transformation determined by the number of each. A tensor with two contravariant indices, , is fully contravariant, while is fully covariant; mixed tensors, such as a (1,1) tensor , have one of each and transform as .[17] This notation ensures the tensor's multilinearity and invariance under coordinate changes, preserving the geometric object it represents.[17] The metric tensor provides a mechanism to raise or lower indices, interconverting between covariant and contravariant forms. To raise a covariant index, one uses the contravariant metric , as in , where the inverse metric satisfies .[18] Conversely, lowering a contravariant index yields .[17] In Euclidean space with the flat metric , this operation is trivial, as covariant and contravariant components coincide numerically.[17] However, in non-Euclidean settings like special relativity, the distinction is essential. The Minkowski metric governs 4-vectors, such as the infinitesimal displacement , whose contravariant components transform under Lorentz boosts, while the covariant form includes the metric's signature to maintain invariance of the interval .[19] This ensures physical quantities like proper time remain coordinate-independent.[19] These index conventions are fundamental in general relativity and differential geometry, where they facilitate the description of curved spacetimes and ensure tensor equations are form-invariant. In general relativity, the metric defines geometry, enabling covariant derivatives and the Riemann curvature tensor, which rely on precise index positioning to capture gravitational effects.[17] In differential geometry, they underpin the transformation laws for manifolds, preserving intrinsic properties like distances and angles under diffeomorphisms.[18]In Computing

Array Indexing Principles

In computing, array indexing refers to the process of accessing individual elements stored in contiguous memory locations using integer offsets from a base address. The memory address of an element in a one-dimensional array is calculated using the formula: address = base address + (index × element size), where the index denotes the position of the element relative to the start of the array and the element size is the number of bytes occupied by each item.[20][21] For instance, consider a one-dimensional array of integers (each 4 bytes) with a base address of 3000; the address of the element at index is given by .[21] A key distinction in array indexing arises between zero-based and one-based conventions. In zero-based indexing, prevalent in computing, indices range from 0 to for an array of elements, aligning with pointer arithmetic where the first element is at offset 0 from the base.[22] This contrasts with one-based indexing, common in mathematics where sequences often start at 1, but computing favors zero-based for its simplicity in address calculations, as the offset directly multiplies by the element size without subtraction.[22] For multidimensional arrays, elements are linearized into a one-dimensional sequence in memory using either row-major or column-major order. In row-major order, elements of each row are stored contiguously, with the address of element in a 2D array calculated as base address + .[21] Column-major order, conversely, stores elements of each column contiguously, reversing the index progression for better cache locality in column-wise operations.[23] These storage conventions ensure efficient traversal but require careful index mapping to compute correct addresses.[21] Bounds checking verifies that indices fall within valid ranges (e.g., 0 to for zero-based arrays) to prevent out-of-bounds access, which can lead to memory corruption, security vulnerabilities, or program crashes.[24] Such checks are crucial in preventing exploits like buffer overflows, a prevalent class of memory errors in low-level languages.[25] The evolution of array indexing traces back to the 1950s with Fortran, which adopted one-based indexing to mirror mathematical notation and simplify scientific computations.[26] Subsequent languages like BCPL in the 1960s introduced zero-based indexing for efficient memory addressing, influencing B and then C in the 1970s, which popularized zero-based defaults in modern computing for their alignment with hardware offsets.[22] Column-major storage originated in early Fortran implementations to optimize vector operations on hardware of the era.[23]Multidimensional Arrays in Programming

In programming, multidimensional arrays extend index notation to represent data structures with multiple dimensions, such as matrices or higher-order tensors, through declarations that specify array sizes in brackets. For instance, in C, the declarationint a[3][4]; creates a two-dimensional array capable of holding 12 integer elements, arranged as 3 rows and 4 columns each, with individual elements accessed using the notation a[i][j] where i ranges from 0 to 2 and j from 0 to 3.

These arrays are typically allocated as a single contiguous block in memory using row-major order, where elements within each row are stored sequentially before moving to the next row. This layout optimizes sequential access along rows, as seen in cache-friendly operations common in numerical computing. For a 3x3 integer matrix declared as int m[3][3];, the memory address of element m[i][j] is computed as the base address plus (i \times 3 + j) \times \sizeof(int), ensuring efficient linear indexing from the flattened storage.[27][28]

In scientific computing and machine learning, index notation, particularly the Einstein summation convention, is implemented to handle tensor operations efficiently. Libraries such as NumPy, PyTorch, and TensorFlow provide the einsum function, which uses index notation to specify tensor contractions, outer products, and other multilinear algebra operations compactly. For example, in NumPy, the dot product of two vectors and can be computed as np.einsum('i,i->', A, B), where repeated indices like i imply summation, mirroring the mathematical convention without explicit loops. This approach simplifies complex expressions in applications like neural network layers and physical simulations.[29][30][31]

Element-wise operations on multidimensional arrays rely on nested loops to iterate over indices, enabling straightforward manipulations like addition or scalar multiplication without requiring specialized libraries for basic cases. For example, adding two 2D arrays a and b of size [m][n] involves a double loop: for each i from 0 to m-1 and j from 0 to n-1, compute c[i][j] = a[i][j] + b[i][j], which directly translates index notation to sequential memory access.[32]

A key challenge arises with jagged arrays, which are implemented as arrays of arrays (e.g., int** jagged in C) allowing rows of unequal lengths, leading to non-contiguous memory that requires explicit stride calculations—such as offsets based on each sub-array's size—for efficient access and traversal.[33]

Modern languages and libraries extend support to higher dimensions, facilitating 3D or greater arrays in applications like scientific simulations, where a 3D array might model spatial grids in fluid dynamics or voxel data in medical imaging, with declaration like double vol[10][20][30]; and access via vol[x][y][z].[34]

Variations Across Languages

In C and C++, array indexing is zero-based, meaning the first element is accessed at index 0, and multidimensional arrays follow row-major order where elements are stored contiguously by rows. This allows efficient pointer arithmetic, such as accessing the i-th element of a one-dimensional array via*(a + i), which directly computes the memory offset from the base address.[35]

Python employs zero-based indexing for both built-in lists and NumPy arrays, supporting flexible slicing operations like a[i:j] for subsets and a[i,j] for two-dimensional access, with additional features such as broadcasting to handle operations across arrays of different shapes without explicit loops.[36] NumPy's advanced indexing, including boolean and integer array indices, further enhances tensor-like manipulations in scientific computing, complemented by einsum for Einstein notation-based operations.[36]

Java also uses zero-based indexing for arrays, with strict static typing requiring declaration of array dimensions at compile time, as in int[][] matrix = new int[rows][cols]; followed by access via matrix[i][j].[37] Unlike C++, Java lacks direct pointer manipulation, emphasizing bounds checking to prevent runtime errors from invalid indices.[37]

Fortran, particularly in its modern standards, defaults to one-based indexing where the first element is at index 1, and arrays are stored in column-major order, optimizing access for scientific simulations by prioritizing contiguous storage along columns.[38] This convention, retained from early versions, allows explicit specification of index bounds, such as REAL :: array(-1:1, 0:10), supporting non-standard ranges for domain-specific modeling.[39]

Julia maintains one-based indexing by default, aligning with mathematical conventions, and supports custom index offsets for arrays, including multidimensional tensors via Cartesian indexing like A[i,j,k].[40] In GPU-accelerated contexts, libraries like CuArrays extend this indexing to CUDA devices, preserving Julia's semantics for high-performance tensor operations without shifting to zero-based conventions.[40]

A notable trend since the 1970s, influenced by the design of C, has been the widespread adoption of zero-based indexing in most general-purpose languages to simplify pointer arithmetic and memory addressing, though domain-specific languages like Fortran and Julia retain one-based indexing for compatibility with scientific and mathematical workflows.[41] Modern libraries, such as NumPy in Python, bridge these differences by providing tensor support that abstracts away storage order variations.[36]