Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

System of linear equations

View on Wikipedia

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (October 2015) |

In mathematics, a system of linear equations (or linear system) is a collection of two or more linear equations involving the same variables.[1][2] For example,

is a system of three equations in the three variables x, y, z. A solution to a linear system is an assignment of values to the variables such that all the equations are simultaneously satisfied. In the example above, a solution is given by the ordered triple since it makes all three equations valid.

Linear systems are a fundamental part of linear algebra, a subject used in most modern mathematics. Computational algorithms for finding the solutions are an important part of numerical linear algebra, and play a prominent role in engineering, physics, chemistry, computer science, and economics. A system of non-linear equations can often be approximated by a linear system (see linearization), a helpful technique when making a mathematical model or computer simulation of a relatively complex system.

Very often, and in this article, the coefficients and solutions of the equations are constrained to be real or complex numbers, but the theory and algorithms apply to coefficients and solutions in any field. For other algebraic structures, other theories have been developed. For coefficients and solutions in an integral domain, such as the ring of integers, see Linear equation over a ring. For coefficients and solutions that are polynomials, see Gröbner basis. For finding the "best" integer solutions among many, see Integer linear programming. For an example of a more exotic structure to which linear algebra can be applied, see Tropical geometry.

Elementary examples

[edit]Trivial example

[edit]The system of one equation in one unknown

has the solution

However, most interesting linear systems have at least two equations.

Simple nontrivial example

[edit]The simplest kind of nontrivial linear system involves two equations and two variables:

One method for solving such a system is as follows. First, solve the top equation for in terms of :

Now substitute this expression for x into the bottom equation:

This results in a single equation involving only the variable . Solving gives , and substituting this back into the equation for yields . This method generalizes to systems with additional variables (see "elimination of variables" below, or the article on elementary algebra.)

General form

[edit]A general system of m linear equations with n unknowns and coefficients can be written as

where are the unknowns, are the coefficients of the system, and are the constant terms.[3]

Often the coefficients and unknowns are real or complex numbers, but integers and rational numbers are also seen, as are polynomials and elements of an abstract algebraic structure.

Vector equation

[edit]One extremely helpful view is that each unknown is a weight for a column vector in a linear combination.

This allows all the language and theory of vector spaces (or more generally, modules) to be brought to bear. For example, the collection of all possible linear combinations of the vectors on the left-hand side (LHS) is called their span, and the equations have a solution just when the right-hand vector is within that span. If every vector within that span has exactly one expression as a linear combination of the given left-hand vectors, then any solution is unique. In any event, the span has a basis of linearly independent vectors that do guarantee exactly one expression; and the number of vectors in that basis (its dimension) cannot be larger than m or n, but it can be smaller. This is important because if we have m independent vectors a solution is guaranteed regardless of the right-hand side (RHS), and otherwise not guaranteed.

Matrix equation

[edit]The vector equation is equivalent to a matrix equation of the form where A is an m×n matrix, x is a column vector with n entries, and b is a column vector with m entries.[4]

The number of vectors in a basis for the span of the columns vectors in A is now expressed as the rank of the matrix.

Solution set

[edit]

A solution of a linear system is an assignment of values to the variables such that each of the equations is satisfied. The set of all possible solutions is called the solution set.[5]

A linear system may behave in any one of three possible ways:

- The system has infinitely many solutions.

- The system has a unique solution.

- The system has no solution.

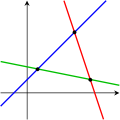

Geometric interpretation

[edit]For a system involving two variables (x and y), each linear equation determines a line on the xy-plane. Because a solution to a linear system must satisfy all of the equations, the solution set is the intersection of these lines, and is hence either a line, a single point, or the empty set.

For three variables, each linear equation determines a plane in three-dimensional space, and the solution set is the intersection of these planes. Thus the solution set may be a plane, a line, a single point, or the empty set. For example, as three parallel planes do not have a common point, the solution set of their equations is empty; the solution set of the equations of three planes intersecting at a point is single point; if three planes pass through two points, their equations have at least two common solutions; in fact the solution set is infinite and consists in all the line passing through these points.[6]

For n variables, each linear equation determines a hyperplane in n-dimensional space. The solution set is the intersection of these hyperplanes, and is a flat, which may have any dimension lower than n.

General behavior

[edit]

In general, the behavior of a linear system is determined by the relationship between the number of equations and the number of unknowns. Here, "in general" means that a different behavior may occur for specific values of the coefficients of the equations.

- In general, a system with fewer equations than unknowns has infinitely many solutions, but it may have no solution. Such a system is known as an underdetermined system.

- In general, a system with the same number of equations and unknowns has a single unique solution.

- In general, a system with more equations than unknowns has no solution. Such a system is also known as an overdetermined system.

In the first case, the dimension of the solution set is, in general, equal to n − m, where n is the number of variables and m is the number of equations.

The following pictures illustrate this trichotomy in the case of two variables:

The first system has infinitely many solutions, namely all of the points on the blue line. The second system has a single unique solution, namely the intersection of the two lines. The third system has no solutions, since the three lines share no common point.

It must be kept in mind that the pictures above show only the most common case (the general case). It is possible for a system of two equations and two unknowns to have no solution (if the two lines are parallel), or for a system of three equations and two unknowns to be solvable (if the three lines intersect at a single point).

A system of linear equations behave differently from the general case if the equations are linearly dependent, or if it is inconsistent and has no more equations than unknowns.

Properties

[edit]Independence

[edit]The equations of a linear system are independent if none of the equations can be derived algebraically from the others. When the equations are independent, each equation contains new information about the variables, and removing any of the equations increases the size of the solution set. For linear equations, logical independence is the same as linear independence.

For example, the equations

are not independent — they are the same equation when scaled by a factor of two, and they would produce identical graphs. This is an example of equivalence in a system of linear equations.

For a more complicated example, the equations

are not independent, because the third equation is the sum of the other two. Indeed, any one of these equations can be derived from the other two, and any one of the equations can be removed without affecting the solution set. The graphs of these equations are three lines that intersect at a single point.

Consistency

[edit]

A linear system is inconsistent if it has no solution, and otherwise, it is said to be consistent.[7] When the system is inconsistent, it is possible to derive a contradiction from the equations, that may always be rewritten as the statement 0 = 1.

For example, the equations

are inconsistent. In fact, by subtracting the first equation from the second one and multiplying both sides of the result by 1/6, we get 0 = 1. The graphs of these equations on the xy-plane are a pair of parallel lines.

It is possible for three linear equations to be inconsistent, even though any two of them are consistent together. For example, the equations

are inconsistent. Adding the first two equations together gives 3x + 2y = 2, which can be subtracted from the third equation to yield 0 = 1. Any two of these equations have a common solution. The same phenomenon can occur for any number of equations.

In general, inconsistencies occur if the left-hand sides of the equations in a system are linearly dependent, and the constant terms do not satisfy the dependence relation. A system of equations whose left-hand sides are linearly independent is always consistent.

Putting it another way, according to the Rouché–Capelli theorem, any system of equations (overdetermined or otherwise) is inconsistent if the rank of the augmented matrix is greater than the rank of the coefficient matrix. If, on the other hand, the ranks of these two matrices are equal, the system must have at least one solution. The solution is unique if and only if the rank equals the number of variables. Otherwise the general solution has k free parameters where k is the difference between the number of variables and the rank; hence in such a case there is an infinitude of solutions. The rank of a system of equations (that is, the rank of the augmented matrix) can never be higher than [the number of variables] + 1, which means that a system with any number of equations can always be reduced to a system that has a number of independent equations that is at most equal to [the number of variables] + 1.

Equivalence

[edit]Two linear systems using the same set of variables are equivalent if each of the equations in the second system can be derived algebraically from the equations in the first system, and vice versa. Two systems are equivalent if either both are inconsistent or each equation of each of them is a linear combination of the equations of the other one. It follows that two linear systems are equivalent if and only if they have the same solution set.

Solving a linear system

[edit]There are several algorithms for solving a system of linear equations.

Describing the solution

[edit]When the solution set is finite, it is reduced to a single element. In this case, the unique solution is described by a sequence of equations whose left-hand sides are the names of the unknowns and right-hand sides are the corresponding values, for example . When an order on the unknowns has been fixed, for example the alphabetical order the solution may be described as a vector of values, like for the previous example.

To describe a set with an infinite number of solutions, typically some of the variables are designated as free (or independent, or as parameters), meaning that they are allowed to take any value, while the remaining variables are dependent on the values of the free variables.

For example, consider the following system:

The solution set to this system can be described by the following equations:

Here z is the free variable, while x and y are dependent on z. Any point in the solution set can be obtained by first choosing a value for z, and then computing the corresponding values for x and y.

Each free variable gives the solution space one degree of freedom, the number of which is equal to the dimension of the solution set. For example, the solution set for the above equation is a line, since a point in the solution set can be chosen by specifying the value of the parameter z. An infinite solution of higher order may describe a plane, or higher-dimensional set.

Different choices for the free variables may lead to different descriptions of the same solution set. For example, the solution to the above equations can alternatively be described as follows:

Here x is the free variable, and y and z are dependent.

Elimination of variables

[edit]The simplest method for solving a system of linear equations is to repeatedly eliminate variables. This method can be described as follows:

- In the first equation, solve for one of the variables in terms of the others.

- Substitute this expression into the remaining equations. This yields a system of equations with one fewer equation and unknown.

- Repeat steps 1 and 2 until the system is reduced to a single linear equation.

- Solve this equation, and then back-substitute until the entire solution is found.

For example, consider the following system:

Solving the first equation for x gives , and plugging this into the second and third equation yields

Since the LHS of both of these equations equal y, equating the RHS of the equations. We now have:

Substituting z = 2 into the second or third equation gives y = 8, and the values of y and z into the first equation yields x = −15. Therefore, the solution set is the ordered triple .

Row reduction

[edit]In row reduction (also known as Gaussian elimination), the linear system is represented as an augmented matrix[8]

This matrix is then modified using elementary row operations until it reaches reduced row echelon form. There are three types of elementary row operations:[8]

- Type 1: Swap the positions of two rows.

- Type 2: Multiply a row by a nonzero scalar.

- Type 3: Add to one row a scalar multiple of another.

Because these operations are reversible, the augmented matrix produced always represents a linear system that is equivalent to the original.

There are several specific algorithms to row-reduce an augmented matrix, the simplest of which are Gaussian elimination and Gauss–Jordan elimination. The following computation shows Gauss–Jordan elimination applied to the matrix above:

The last matrix is in reduced row echelon form, and represents the system x = −15, y = 8, z = 2. A comparison with the example in the previous section on the algebraic elimination of variables shows that these two methods are in fact the same; the difference lies in how the computations are written down.

Cramer's rule

[edit]Cramer's rule is an explicit formula for the solution of a system of linear equations, with each variable given by a quotient of two determinants.[9] For example, the solution to the system

is given by

For each variable, the denominator is the determinant of the matrix of coefficients, while the numerator is the determinant of a matrix in which one column has been replaced by the vector of constant terms.

Though Cramer's rule is important theoretically, it has little practical value for large matrices, since the computation of large determinants is somewhat cumbersome. (Indeed, large determinants are most easily computed using row reduction.) Further, Cramer's rule has very poor numerical properties, making it unsuitable for solving even small systems reliably, unless the operations are performed in rational arithmetic with unbounded precision.[citation needed]

Matrix solution

[edit]If the equation system is expressed in the matrix form , the entire solution set can also be expressed in matrix form. If the matrix A is square (has m rows and n=m columns) and has full rank (all m rows are independent), then the system has a unique solution given by

where is the inverse of A. More generally, regardless of whether m=n or not and regardless of the rank of A, all solutions (if any exist) are given using the Moore–Penrose inverse of A, denoted , as follows:

where is a vector of free parameters that ranges over all possible n×1 vectors. A necessary and sufficient condition for any solution(s) to exist is that the potential solution obtained using satisfy — that is, that If this condition does not hold, the equation system is inconsistent and has no solution. If the condition holds, the system is consistent and at least one solution exists. For example, in the above-mentioned case in which A is square and of full rank, simply equals and the general solution equation simplifies to

as previously stated, where has completely dropped out of the solution, leaving only a single solution. In other cases, though, remains and hence an infinitude of potential values of the free parameter vector give an infinitude of solutions of the equation.

Other methods

[edit]While systems of three or four equations can be readily solved by hand (see Cracovian), computers are often used for larger systems. The standard algorithm for solving a system of linear equations is based on Gaussian elimination with some modifications. Firstly, it is essential to avoid division by small numbers, which may lead to inaccurate results. This can be done by reordering the equations if necessary, a process known as pivoting. Secondly, the algorithm does not exactly do Gaussian elimination, but it computes the LU decomposition of the matrix A. This is mostly an organizational tool, but it is much quicker if one has to solve several systems with the same matrix A but different vectors b.

If the matrix A has some special structure, this can be exploited to obtain faster or more accurate algorithms. For instance, systems with a symmetric positive definite matrix can be solved twice as fast with the Cholesky decomposition. Levinson recursion is a fast method for Toeplitz matrices. Special methods exist also for matrices with many zero elements (so-called sparse matrices), which appear often in applications.

A completely different approach is often taken for very large systems, which would otherwise take too much time or memory. The idea is to start with an initial approximation to the solution (which does not have to be accurate at all), and to change this approximation in several steps to bring it closer to the true solution. Once the approximation is sufficiently accurate, this is taken to be the solution to the system. This leads to the class of iterative methods. For some sparse matrices, the introduction of randomness improves the speed of the iterative methods.[10] One example of an iterative method is the Jacobi method, where the matrix is split into its diagonal component and its non-diagonal component . An initial guess is used at the start of the algorithm. Each subsequent guess is computed using the iterative equation:

When the difference between guesses and is sufficiently small, the algorithm is said to have converged on the solution.[11]

There is also a quantum algorithm for linear systems of equations.[12]

Homogeneous systems

[edit]A system of linear equations is homogeneous if all of the constant terms are zero:

A homogeneous system is equivalent to a matrix equation of the form

where A is an m × n matrix, x is a column vector with n entries, and 0 is the zero vector with m entries.

Homogeneous solution set

[edit]Every homogeneous system has at least one solution, known as the zero (or trivial) solution, which is obtained by assigning the value of zero to each of the variables. If the system has a non-singular matrix (det(A) ≠ 0) then it is also the only solution. If the system has a singular matrix then there is a solution set with an infinite number of solutions. This solution set has the following additional properties:

- If u and v are two vectors representing solutions to a homogeneous system, then the vector sum u + v is also a solution to the system.

- If u is a vector representing a solution to a homogeneous system, and r is any scalar, then ru is also a solution to the system.

These are exactly the properties required for the solution set to be a linear subspace of Rn. In particular, the solution set to a homogeneous system is the same as the null space of the corresponding matrix A.

Relation to nonhomogeneous systems

[edit]There is a close relationship between the solutions to a linear system and the solutions to the corresponding homogeneous system:

Specifically, if p is any specific solution to the linear system Ax = b, then the entire solution set can be described as

Geometrically, this says that the solution set for Ax = b is a translation of the solution set for Ax = 0. Specifically, the flat for the first system can be obtained by translating the linear subspace for the homogeneous system by the vector p.

This reasoning only applies if the system Ax = b has at least one solution. This occurs if and only if the vector b lies in the image of the linear transformation A.

See also

[edit]- Arrangement of hyperplanes

- Iterative refinement – Method to improve accuracy of numerical solutions to systems of linear equations

- Coates graph – Mathematical graph for solving linear systems

- LAPACK – Software library for numerical linear algebra

- Linear equation over a ring

- Linear least squares – Least squares approximation of linear functions to data

- Matrix decomposition – Representation of a matrix as a product

- Matrix splitting – Representation of a matrix as a sum

- NAG Numerical Library – Software library of numerical-analysis algorithms

- Rybicki Press algorithm – Algorithm for inverting a matrix

- Simultaneous equations – Set of equations to be solved together

References

[edit]- ^ Anton (1987), p. 2; Burden & Faires (1993), p. 324; Golub & Van Loan (1996), p. 87; Harper (1976), p. 57.

- ^ "System of Equations". Britannica. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Beauregard & Fraleigh (1973), p. 65.

- ^ Beauregard & Fraleigh (1973), pp. 65–66.

- ^ "Systems of Linear Equations" (PDF). math.berkeley.edu. Retrieved February 3, 2025.

- ^ Cullen (1990), p. 3.

- ^ Whitelaw (1991), p. 70.

- ^ a b Beauregard & Fraleigh (1973), p. 68.

- ^ Sterling (2009), p. 235.

- ^ Hartnett, Kevin (March 8, 2021). "New Algorithm Breaks Speed Limit for Solving Linear Equations". Quanta Magazine. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- ^ "Jacobi Method".

- ^ Harrow, Hassidim & Lloyd (2009).

Bibliography

[edit]- Anton, Howard (1987), Elementary Linear Algebra (5th ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-84819-0

- Beauregard, Raymond A.; Fraleigh, John B. (1973), A First Course In Linear Algebra: with Optional Introduction to Groups, Rings, and Fields, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, ISBN 0-395-14017-X

- Burden, Richard L.; Faires, J. Douglas (1993), Numerical Analysis (5th ed.), Boston: Prindle, Weber and Schmidt, ISBN 0-534-93219-3

- Cullen, Charles G. (1990), Matrices and Linear Transformations, MA: Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-66328-9

- Golub, Gene H.; Van Loan, Charles F. (1996), Matrix Computations (3rd ed.), Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0-8018-5414-8

- Harper, Charlie (1976), Introduction to Mathematical Physics, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, ISBN 0-13-487538-9

- Harrow, Aram W.; Hassidim, Avinatan; Lloyd, Seth (2009), "Quantum Algorithm for Linear Systems of Equations", Physical Review Letters, 103 (15) 150502, arXiv:0811.3171, Bibcode:2009PhRvL.103o0502H, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.103.150502, PMID 19905613, S2CID 5187993

- Sterling, Mary J. (2009), Linear Algebra for Dummies, Indianapolis, Indiana: Wiley, ISBN 978-0-470-43090-3

- Whitelaw, T. A. (1991), Introduction to Linear Algebra (2nd ed.), CRC Press, ISBN 0-7514-0159-5

Further reading

[edit]- Axler, Sheldon Jay (1997). Linear Algebra Done Right (2nd ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-98259-0.

- Lay, David C. (August 22, 2005). Linear Algebra and Its Applications (3rd ed.). Addison Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-28713-7.

- Meyer, Carl D. (February 15, 2001). Matrix Analysis and Applied Linear Algebra. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM). ISBN 978-0-89871-454-8. Archived from the original on March 1, 2001.

- Poole, David (2006). Linear Algebra: A Modern Introduction (2nd ed.). Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0-534-99845-3.

- Anton, Howard (2005). Elementary Linear Algebra (Applications Version) (9th ed.). Wiley International.

- Leon, Steven J. (2006). Linear Algebra With Applications (7th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Strang, Gilbert (2005). Linear Algebra and Its Applications.

- Peng, Richard; Vempala, Santosh S. (2024). "Solving Sparse Linear Systems Faster than Matrix Multiplication". Comm. ACM. 67 (7): 79–86. arXiv:2007.10254. doi:10.1145/3615679.

External links

[edit] Media related to System of linear equations at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to System of linear equations at Wikimedia Commons

System of linear equations

View on GrokipediaBasic Concepts

Definition

A linear equation in variables is an equation that can be expressed in the form where the coefficients and the constant term are real numbers, and not all coefficients are zero.[12] This form represents a first-degree polynomial equation in the variables, with each term being either a constant or the product of a constant and a single variable raised to the first power.[13] A system of linear equations is a collection of one or more linear equations involving the same set of variables, where the goal is typically to find values of the variables that satisfy all equations simultaneously.[4] The variables serve as unknowns, while the coefficients and constants are given real numbers, assuming familiarity with basic algebraic operations over the real numbers without prior knowledge of advanced structures like matrices.[14] In standard notation, the scalar form introduced here uses lowercase letters for variables and subscripts for coefficients, with boldface reserved for vector or matrix representations in subsequent discussions.[15]Elementary Examples

A system of linear equations can consist of a single equation, which is considered a trivial case. For instance, the equation in one variable has a unique solution, , as it directly specifies the value of the variable.[2] A simple nontrivial example involves two equations in two variables, such as To solve this using substitution, first isolate one variable from the second equation: . Substitute into the first equation: , which simplifies to , so . Then, . The unique solution is , .[16] In small-scale systems, the number of equations relative to variables affects the solutions. An underdetermined system, like one equation in two variables such as , has infinitely many solutions, parameterized as for any .[17] Conversely, an overdetermined system, like two equations in one variable such as and , has no solution due to the contradiction.[17]Mathematical Representation

General Form

A system of linear equations in variables over a field, typically the real numbers or complex numbers , takes the general form where the (for and ) are the coefficients belonging to the field, and the (for ) are the constant terms also in the field.[1] This representation generalizes the elementary cases of two or three equations to arbitrary dimensions, allowing for overdetermined (), underdetermined (), or square () systems, with solutions sought in the field's vector space.[18] To facilitate analysis, the system can be compactly represented using the augmented coefficient matrix , formed by juxtaposing the coefficient matrix with the column vector : This matrix encodes the entire system without altering its solution set, serving as a foundational tool for further manipulations, though row operations to solve it are addressed elsewhere.[19] The focus here remains on finite systems, as infinite systems of linear equations, which arise in functional analysis or infinite-dimensional spaces, fall outside this scope.[18] The study of such systems traces back to ancient civilizations, notably the Babylonians around 1800 BCE, who inscribed practical problems leading to simultaneous linear equations on clay tablets, often involving ratios in trade, agriculture, or geometry, and solved them using methods akin to substitution.[9] These early tablet-based approaches demonstrate an intuitive grasp of balancing equations for real-world applications, predating formal algebraic notation by millennia.[20]Vector and Matrix Forms

A system of linear equations can be expressed in a compact vector and matrix form, transforming the expanded scalar equations into a single matrix equation . Here, is the coefficient matrix whose entries are the coefficients of the variables from the original system, is the column vector containing the unknown variables, and is the column vector of constant terms.[21] This notation assumes the general form of the system, where each equation is a linear combination of variables equal to a constant.[22] The structure of the coefficient matrix , which is for a system of equations in variables, organizes the coefficients such that each row corresponds to the coefficients of one equation, and each column corresponds to the coefficients of one variable across all equations.[23] The vector is , listing the variables , while is , listing the constants . The equation is defined through standard matrix-vector multiplication, where the -th entry of equals the -th entry of ./02%3A_Matrix_Arithmetic/2.04%3A_Vector_Solutions_to_Linear_Systems) For illustration, consider a system of two equations in two variables: In matrix form, this becomes The first row of captures the coefficients 2 and 3 from the first equation, the second row captures 4 and 1 from the second, the first column relates to , and the second to .[24] This vector and matrix representation offers advantages in algebraic manipulation, as it condenses multiple equations into one, enabling unified operations on the system, and enhances computational efficiency when implemented in algorithms or software for handling larger systems.[25] It presupposes an understanding of matrix multiplication, which directly corresponds to the linear combinations in the general scalar form of the equations.[21]Solution Sets

Geometric Interpretation

In two dimensions, each linear equation in two variables represents a straight line in the plane. The solution to a system of such equations corresponds to the intersection points of these lines: a unique solution occurs when the lines intersect at a single point, infinitely many solutions arise when the lines are coincident (overlapping completely), and no solution exists when the lines are parallel and distinct.[26] Extending to three dimensions, each linear equation defines a plane in space. The solution set for a system is the common intersection of these planes, which may result in a single point (unique solution), a line (infinitely many solutions along that line), or no intersection at all if the planes do not meet.[27] In higher dimensions, this geometric view generalizes to hyperplanes, where each equation specifies an (n-1)-dimensional hyperplane in n-dimensional space. The solution set of the system is the intersection of these hyperplanes, forming an affine subspace whose dimension depends on the dependencies among the equations; for instance, consistent systems yield intersections ranging from a point to higher-dimensional flats.[28] This parametric representation aligns with the vector form of solutions, depicting the set as a translate of the null space of the coefficient matrix.[27]Classification of Solutions

The solutions to a system of linear equations , where is an matrix over a field such as the real numbers, can be classified into three categories based on the ranks of the coefficient matrix and the augmented matrix . A system has no solution if the rank of is strictly less than the rank of , indicating inconsistency because the right-hand side introduces additional linear independence not present in the rows of . The system has a unique solution if the rank of equals the rank of and both equal (the number of variables), meaning has full column rank and the system is determined. It has infinitely many solutions if the rank of equals the rank of but is less than , corresponding to an underdetermined system where the solution set forms an affine subspace of dimension , with the common rank. This classification is formalized by the Rouché–Capelli theorem, which states that a system is consistent (has at least one solution) if and only if , and the dimension of the solution set is then . A brief proof sketch relies on row reduction: performing Gaussian elimination on yields a row echelon form where the number of nonzero rows gives . If this rank exceeds (computed similarly from alone), a row with zeros in the coefficient part but nonzero in the augmented part signals inconsistency. Otherwise, back-substitution reveals either a unique solution (when there are pivots) or free variables leading to infinitely many solutions (fewer than pivots). Determining this classification computationally is polynomial-time efficient over the reals or rationals, as Gaussian elimination computes the ranks in arithmetic operations in the worst case for square systems, though more refined analyses yield for general matrices.Key Properties

Linear Independence

In the context of a system of linear equations represented by the matrix equation , where is an matrix, the linear independence of the rows or columns of plays a fundamental role in determining the structure of the solution set. A set of vectors, such as the rows or columns of , is linearly independent if the only solution to the equation is the trivial solution where all coefficients , meaning no nontrivial linear combination yields the zero vector.[29] This property ensures that none of the vectors can be expressed as a linear combination of the others.[30] For the rows of , which correspond to the individual equations in the system, linear independence implies that there are no redundant equations; each equation provides unique information not derivable from the others. Similarly, linear independence of the columns of reflects the independence among the variables' coefficients. If the rows (or columns) are fully linearly independent—meaning the rank of equals the minimum of and —this structural property supports the potential for a unique solution in square systems or constrains the solution space in rectangular ones.[31] In particular, for a square matrix , the columns are linearly independent if and only if the determinant of is nonzero, as a zero determinant indicates a nontrivial solution to .[32] Consider a system with coefficient matrix . The columns and are linearly independent precisely when , ensuring the homogeneous system has only the trivial solution and the original system has a unique solution for any .[33] This example illustrates how linear independence directly ties to solvability. Linear independence also connects to the concepts of basis and span in describing the solution space of the homogeneous system , whose solutions form the null space of . A basis for the null space is a linearly independent set of vectors that spans the entire null space, and the dimension of this solution space (nullity) is minus the dimension of the column space of , where the column space dimension equals the number of linearly independent columns (the rank). Thus, greater independence among the columns reduces the dimension of the solution space, potentially to zero for full rank.[34] The row space similarly has a basis consisting of linearly independent rows, spanning all linear combinations of the equations.[35]Consistency and Uniqueness

A system of linear equations , where is an matrix and is an -dimensional vector, is consistent if it possesses at least one solution. The necessary and sufficient condition for consistency is that the rank of the coefficient matrix equals the rank of the augmented matrix , denoted as This result, known as the Rouché–Capelli theorem, determines whether the vector lies in the column space of . If the ranks differ, the system is inconsistent and has no solutions./01%3A_Systems_of_Equations/1.05%3A_Rank_and_Homogeneous_Systems) For a consistent system, the solution is unique if and only if , where is the number of variables. In this case, the columns of are linearly independent, ensuring the solution set consists of exactly one point. If , the solution set is infinite, forming an affine subspace of dimension . This full-rank condition on serves as a prerequisite for uniqueness in consistent systems./01%3A_Systems_of_Equations/1.05%3A_Rank_and_Homogeneous_Systems) Two systems of linear equations are equivalent if they share the same solution set. Elementary row operations applied to the augmented matrix preserve this solution set, meaning that any system obtained via such operations is equivalent to the original. Consequently, two systems are equivalent if and only if their augmented matrices are row equivalent. In finite-dimensional spaces, the Fredholm alternative provides a foundational dichotomy for solvability: for the operator defined by , either the homogeneous equation has only the trivial solution (implying a unique solution for every ), or it has non-trivial solutions (implying solvability of only when is orthogonal to the left kernel of , with infinitely many solutions otherwise). For consistent systems, solvability is guaranteed by the rank condition, aligning with this alternative.[36]Solution Methods

There are several standard methods for solving systems of linear equations, many of which are taught in secondary schools and universities. These methods vary in approach, computational efficiency, and suitability depending on the number of variables, system size, and context. Common methods include:- Substitution method: Solve one equation for one variable and substitute the resulting expression into the remaining equations, reducing the system step by step until a solution is obtained.

- Elimination method (also known as addition or subtraction method): Multiply equations by appropriate constants to make the coefficients of one variable equal in magnitude but opposite in sign (if necessary), then add or subtract the equations to eliminate that variable, repeating the process until all variables are solved. Detailed steps and an example are provided in the Elimination method subsection.

- Graphical method: Represent the equations as lines in the coordinate plane and identify their intersection points (primarily practical for systems with two variables).

- Cramer's rule: Compute each variable as the ratio of two determinants, using the coefficient matrix and matrices modified by replacing columns with the constant vector (applicable when the coefficient matrix is invertible).

- Gaussian elimination (or Gauss-Jordan elimination): Apply elementary row operations to the augmented matrix to transform it into row echelon form (or reduced row echelon form) and solve via back-substitution.

- Matrix inverse method: If the coefficient matrix is invertible, multiply both sides of the matrix equation by its inverse to obtain the solution vector directly.

Elimination Method

The elimination method solves systems of linear equations by adding or subtracting multiples of the equations to eliminate one variable at a time. This technique is especially straightforward for small systems (typically two or three variables) and serves as a foundation for more systematic approaches like Gaussian elimination used in larger systems. Step-by-step process:- Align the equations in standard form (Ax + By = C for two variables).

- Choose a variable to eliminate. Multiply one or both equations by constants to make the coefficients of that variable equal in magnitude but opposite in sign (skip if already the case).

- Add the modified equations to eliminate the chosen variable, resulting in a single-variable equation.

- Solve the new equation for the remaining variable.

- Substitute this value back into one of the original equations to solve for the next variable.

- Check the solution in both (or all) original equations to verify.

2x + 3y = 8

4x - y = 7 To eliminate y, multiply the second equation by 3:

12x - 3y = 21 Add to the first:

(2x + 3y) + (12x - 3y) = 8 + 21

14x = 29

x = 29/14 Substitute into the second equation:

4(29/14) - y = 7

116/14 - y = 98/14

y = 116/14 - 98/14 = 18/14 = 9/7 Solution: (29/14, 9/7).[37]

![{\displaystyle \left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}1&3&-2&5\\3&5&6&7\\2&4&3&8\end{array}}\right]{\text{.}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/6d99c79eb45b325d779be9693c613d9aec07b6d4)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}1&3&-2&5\\3&5&6&7\\2&4&3&8\end{array}}\right]&\sim \left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}1&3&-2&5\\0&-4&12&-8\\2&4&3&8\end{array}}\right]\sim \left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}1&3&-2&5\\0&-4&12&-8\\0&-2&7&-2\end{array}}\right]\sim \left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}1&3&-2&5\\0&1&-3&2\\0&-2&7&-2\end{array}}\right]\\&\sim \left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}1&3&-2&5\\0&1&-3&2\\0&0&1&2\end{array}}\right]\sim \left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}1&3&-2&5\\0&1&0&8\\0&0&1&2\end{array}}\right]\sim \left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}1&3&0&9\\0&1&0&8\\0&0&1&2\end{array}}\right]\sim \left[{\begin{array}{rrr|r}1&0&0&-15\\0&1&0&8\\0&0&1&2\end{array}}\right].\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5f6367f306a7947555dd25f9b3b29a5903efdabb)