Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Shorthand

View on Wikipedia

Shorthand is an abbreviated symbolic writing method that increases speed and brevity of writing as compared to longhand, a more common method of writing a language. The process of writing in shorthand is called stenography, from the Greek stenos (narrow) and graphein (to write). It has also been called brachygraphy, from Greek brachys (short), and tachygraphy, from Greek tachys (swift, speedy), depending on whether compression or speed of writing is the goal.

Many forms of shorthand exist. A typical shorthand system provides symbols or abbreviations for words and common phrases, which can allow someone well-trained in the system to write as quickly as people speak. Abbreviation methods are alphabet-based and use different abbreviating approaches. Many journalists use shorthand writing to quickly take notes at press conferences or other similar scenarios. In the computerized world, several autocomplete programs, standalone or integrated in text editors, based on word lists, also include a shorthand function for frequently used phrases.

Shorthand was used more widely in the past, before the invention of recording and dictation machines. Shorthand was considered an essential part of secretarial training and police work and was useful for journalists.[1] Although the primary use of shorthand has been to record oral dictation and other types of verbal communication, some systems are used for compact expression. For example, healthcare professionals might use shorthand notes in medical charts and correspondence. Shorthand notes were typically temporary, intended either for immediate use or for later typing, data entry, or (mainly historically) transcription to longhand. Longer-term uses do exist, such as encipherment; diaries (like that of Samuel Pepys) are a common example.[2]

History

[edit]Classical antiquity

[edit]The earliest known indication of shorthand systems is from the Parthenon in Ancient Greece, where a mid-4th century BC inscribed marble slab was found. This shows a writing system primarily based on vowels, using certain modifications to indicate consonants.[3] Hellenistic tachygraphy is reported from the 2nd century BC onwards, though there are indications that it might be older. The oldest datable reference is a contract from Middle Egypt, stating that Oxyrhynchos gives the "semeiographer" Apollonios for two years to be taught shorthand writing.[4] Hellenistic tachygraphy consisted of word stem signs and word ending signs. Over time, many syllabic signs were developed.

In Ancient Rome, Marcus Tullius Tiro (103–4 BC), a slave and later a freedman of Cicero, developed the Tironian notes so that he could write down Cicero's speeches. Plutarch (c. 46 – c. 120 AD) in his "Life of Cato the Younger" (95–46 BC) records that Cicero, during a trial of some insurrectionists in the senate, employed several expert rapid writers, whom he had taught to make figures comprising numerous words in a few short strokes, to preserve Cato's speech on this occasion. The Tironian notes consisted of Latin word stem abbreviations (notae) and of word ending abbreviations (titulae). The original Tironian notes consisted of about 4,000 signs, but new signs were introduced, so that their number might increase to as many as 13,000. In order to have a less complex writing system, a syllabic shorthand script was sometimes used. After the decline of the Roman Empire, the Tironian notes were no longer used to transcribe speeches, though they were still known and taught, particularly during the Carolingian Renaissance. After the 11th century, however, they were mostly forgotten.

When many monastery libraries were secularized in the course of the 16th-century Protestant Reformation, long-forgotten manuscripts of Tironian notes were rediscovered.[citation needed]

Imperial China

[edit]

In imperial China, clerks used an abbreviated, highly cursive form of Chinese characters to record court proceedings and criminal confessions. These records were used to create more formal transcripts. One cornerstone of imperial court proceedings was that all confessions had to be acknowledged by the accused's signature, personal seal, or thumbprint, requiring fast writing.[citation needed] Versions of this technique survived in clerical professions into the modern day and, influenced by Western shorthand methods, some new methods were invented.[5][6][7][8]

Europe and North America

[edit]

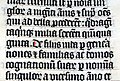

An interest in shorthand or "short-writing" developed towards the end of the 16th century in England. In 1588, Timothy Bright published his Characterie; An Arte of Shorte, Swifte and Secrete Writing by Character which introduced a system with 500 arbitrary symbols each representing one word. Bright's book was followed by a number of others, including Peter Bales' The Writing Schoolemaster in 1590, John Willis's Art of Stenography in 1602, Edmond Willis's An abbreviation of writing by character in 1618, and Thomas Shelton's Short Writing in 1626 (later re-issued as Tachygraphy).

Shelton's system became very popular and is well known because it was used by Samuel Pepys for his diary and for many of his official papers, such as his letter copy books. It was also used by Isaac Newton in some of his notebooks.[9] Shelton borrowed heavily from his predecessors, especially Edmond Willis. Each consonant was represented by an arbitrary but simple symbol, while the five vowels were represented by the relative positions of the surrounding consonants. Thus the symbol for B with symbol for T drawn directly above it represented "bat", while B with T below it meant "but"; top-right represented "e", middle-right "i", and lower-right "o". A vowel at the end of a word was represented by a dot in the appropriate position, while there were additional symbols for initial vowels. This basic system was supplemented by further symbols representing common prefixes and suffixes.

One drawback of Shelton's system was that there was no way to distinguish long and short vowels or diphthongs; so the b-a-t sequence could mean "bat", or "bait", or "bate", while b-o-t might mean "boot", or "bought", or "boat". The reader needed to use the context to work out which alternative was meant. The main advantage of the system was that it was easy to learn and to use. It was popular, and under the two titles of Short Writing and Tachygraphy, Shelton's book ran to more than 20 editions between 1626 and 1710.

Shelton's chief rivals were Theophilus Metcalfe's Stenography or Short Writing (1633) which was in its "55th edition" by 1721, and Jeremiah Rich's system of 1654, which was published under various titles including The penns dexterity compleated (1669). Rich's system was used by George Treby chairman of the House of Commons Committee of Secrecy investigating the Popish Plot.[10] Another English shorthand system creator of the 17th century was William Mason (fl. 1672–1709) who published Arts Advancement in 1682.

Modern-looking geometric shorthand was introduced with John Byrom's New Universal Shorthand of 1720. Samuel Taylor published a similar system in 1786, the first English shorthand system to be used all over the English-speaking world. Thomas Gurney published Brachygraphy in the mid-18th century. In 1834 in Germany, Franz Xaver Gabelsberger published his Gabelsberger shorthand. Gabelsberger based his shorthand on the shapes used in German cursive handwriting rather than on the geometrical shapes that were common in the English stenographic tradition.

Taylor's system was superseded by Pitman shorthand, first introduced in 1837 by English teacher Isaac Pitman, and improved many times since. Pitman's system has been used all over the English-speaking world and has been adapted to many other languages, including Latin.[citation needed] Pitman's system uses a phonemic orthography. For this reason, it is sometimes known as phonography, meaning "sound writing" in Greek. One of the reasons this system allows fast transcription is that vowel sounds are optional when only consonants are needed to determine a word. The availability of a full range of vowel symbols, however, makes complete accuracy possible. Isaac's brother Benn Pitman, who lived in Cincinnati, Ohio, was responsible for introducing the method to America. The record for fast writing with Pitman shorthand is 350 wpm during a two-minute test by Nathan Behrin in 1922.[11]

In the United States and some other parts of the world, it was largely superseded by Gregg shorthand, which was first published in 1888 by John Robert Gregg. This system was influenced by the handwriting shapes that Gabelsberger had introduced. Gregg's shorthand, like Pitman's, is phonetic, but has the simplicity of being "light-line." Pitman's system uses thick and thin strokes to distinguish related sounds, while Gregg's uses only thin strokes and makes some of the same distinctions by the length of the stroke. In fact, Gregg claimed joint authorship in another shorthand system published in pamphlet form by one Thomas Stratford Malone; Malone, however, claimed sole authorship and a legal battle ensued.[12] The two systems use very similar, if not identical, symbols; however, these symbols are used to represent different sounds. For instance, on page 10 of the manual is the word d i m 'dim'; however, in the Gregg system, the spelling would actually mean n u k or 'nook'.[13]

Andrew J. Graham was a phonotypist operating in the period between the emergence of Pitman's and Gregg's systems. In 1854 he published a short-lived (only 9 issues) phonotypy journal called The Cosmotype, subtitled "devoted to that which will entertain usefully, instruct, and improve humanity",[14][15] and several other monographs about phonography.[16] In 1857 he published his own Pitman-like "Graham's Brief Longhand" that saw wide adoption in the United States in the late 19th century.[16] He published a translation of the New Testament. His method landed him in a 1864 copyright infringement lawsuit against Benn Pitman in Ohio.[16] Graham died in 1895 and was buried in Montclair's Rosedale Cemetery; even as late as 1918 his company Andrew J. Graham & Co continued to market his method.[17]

In his youth, Woodrow Wilson had mastered the Graham system and even corresponded with Graham in Graham. Throughout his life, Wilson continued to develop and employ his own Graham system writing, to the point that by the 1950s, when the Graham method had all but disappeared, Wilson scholars had trouble interpreting his shorthand. In 1960 an 84-year-old anachronistic shorthand expert Clifford Gehman managed to crack Wilson's shorthand, demonstrating on a translation of Wilson's acceptance speech for the 1912 presidential nomination.[18][19]

Japan

[edit]Our Japanese pen shorthand began in 1882, transplanted from the American Pitman-Graham system. Geometric theory has great influence in Japan. But Japanese motions of writing gave some influence to our shorthand. We are proud to have reached the highest speed in capturing spoken words with a pen. Major pen shorthand systems are Shuugiin, Sangiin, Nakane and Waseda [a repeated vowel shown here means a vowel spoken in double-length in Japanese, sometimes shown instead as a bar over the vowel]. Including a machine-shorthand system, Sokutaipu, we have 5 major shorthand systems now. The Japan Shorthand Association now has 1,000 members.

— Tsuguo Kaneko[20]

There are several other pen shorthands in use (Ishimura, Iwamura, Kumassaki, Kotani, and Nissokuken), leading to a total of nine pen shorthands in use. In addition, there is the Yamane pen shorthand (of unknown importance) and three machine shorthands systems (Speed Waapuro, Caver and Hayatokun or sokutaipu). The machine shorthands have gained some ascendancy over the pen shorthands.[21]

Japanese shorthand systems ('sokki' shorthand or 'sokkidou' stenography) commonly use a syllabic approach, much like the common writing system for Japanese (which has actually two syllabaries in everyday use). There are several semi-cursive systems.[22] Most follow a left-to-right, top-to-bottom writing direction.[23] Several systems incorporate a loop into many of the strokes, giving the appearance of Gregg, Graham, or Cross's Eclectic shorthand without actually functioning like them.[24] The Kotani (aka Same-Vowel-Same-Direction or SVSD or V-type)[25] system's strokes frequently cross over each other and in so doing form loops.[26]

Japanese also has its own variously cursive form of writing kanji characters, the most extremely simplified of which is known as Sōsho.

The two Japanese syllabaries are themselves adapted from the Chinese characters: both of the syllabaries, katakana and hiragana, are in everyday use alongside the Chinese characters known as kanji; the kanji, being developed in parallel to the Chinese characters, have their own idiosyncrasies, but Chinese and Japanese ideograms are largely comprehensible, even if their use in the languages are not the same.

Prior to the Meiji era, Japanese did not have its own shorthand (the kanji did have their own abbreviated forms borrowed alongside them from China). Takusari Kooki was the first to give classes in a new Western-style non-ideographic shorthand of his own design, emphasis being on the non-ideographic and new. This was the first shorthand system adapted to writing phonetic Japanese, all other systems prior being based on the idea of whole or partial semantic ideographic writing like that used in the Chinese characters, and the phonetic approach being mostly peripheral to writing in general. Even today, Japanese writing uses the syllabaries to pronounce or spell out words, or to indicate grammatical words. Furigana are written alongside kanji, or Chinese characters, to indicate their pronunciation especially in juvenile publications. Furigana are usually written using the hiragana syllabary; foreign words may not have a kanji form and are spelled out using katakana.[27]

The new sokki were used to transliterate popular vernacular story-telling theater (yose) of the day. This led to a thriving industry of sokkibon (shorthand books). The ready availability of the stories in book form, and higher rates of literacy (which the very industry of sokkibon may have helped create, due to these being oral classics that were already known to most people) may also have helped kill the yose theater, as people no longer needed to see the stories performed in person to enjoy them. Sokkibon also allowed a whole host of what had previously been mostly oral rhetorical and narrative techniques into writing, such as imitation of dialect in conversations (which can be found back in older gensaku literature; but gensaku literature used conventional written language in between conversations, however).[28]

Classification

[edit]Geometric and script-like systems

[edit]Shorthands that use simplified letterforms are sometimes termed stenographic shorthands, contrasting with alphabetic shorthands, below. Stenographic shorthands can be further differentiated by the target letter forms as geometric, script, and semi-script or elliptical.

Geometric shorthands are based on circles, parts of circles, and straight lines placed strictly horizontally, vertically or diagonally. The first modern shorthand systems were geometric. Examples include Pitman shorthand, Boyd's syllabic shorthand, Samuel Taylor's Universal Stenography, the French Prévost-Delaunay, and the Duployé system, adapted to write the Kamloops Wawa (used for Chinook Jargon) writing system.[29]

Script shorthands are based on the motions of ordinary handwriting. The first system of this type was published under the title Cadmus Britanicus by Simon Bordley, in 1787. However, the first practical system was the German Gabelsberger shorthand of 1834. This class of system is now common in all more recent German shorthand systems, as well as in Austria, Italy, Scandinavia, the Netherlands, Russia, other Eastern European countries, and elsewhere.

Script-geometric, or semi-script, shorthands are based on the ellipse. Semi-script can be considered a compromise between the geometric systems and the script systems. The first such system was that of George Carl Märes in 1885. However, the most successful system of this type was Gregg shorthand, introduced by John Robert Gregg in 1888. Gregg had studied not only the geometric English systems, but also the German Stolze stenography, a script shorthand. Other examples include Teeline Shorthand and Thomas Natural Shorthand.

The semi-script philosophy gained popularity in Italy in the first half of the 20th century with three different systems created by Giovanni Vincenzo Cima, Erminio Meschini, and Stenital Mosciaro.

Systems resembling standard writing

[edit]Some shorthand systems attempted to ease learning by using characters from the Latin alphabet. Such non-stenographic systems have often been described as alphabetic, and purists[who?] might claim that such systems are not 'true' shorthand. However, these alphabetic systems do have value for students who cannot dedicate the years necessary to master a stenographic shorthand. Alphabetic shorthands cannot be written at the speeds theoretically possible with symbol systems—200 words per minute or more—but require only a fraction of the time to acquire a useful speed of between 70 and 100 words per minute.

Non-stenographic systems often supplement alphabetic characters by using punctuation marks as additional characters, giving special significance to capitalised letters, and sometimes using additional non-alphabetic symbols. Examples of such systems include Stenoscript, Speedwriting and Forkner shorthand. However, there are some pure alphabetic systems, including Personal Shorthand, SuperWrite, Easy Script Speed Writing, Keyscript Shorthand and Yash3k which limit their symbols to a priori alphabetic characters. These have the added advantage that they can also be typed—for instance, onto a computer, PDA, or cellphone. Early editions of Speedwriting were also adapted so that they could be written on a typewriter, and therefore would possess the same advantage.

Varieties of vowel representation

[edit]Shorthand systems can also be classified according to the way that vowels are represented.

- Alphabetic – Expression by "normal" vowel signs that are not fundamentally different from consonant signs (e.g., Gregg, Duployan).

- Mixed alphabetic – Expression of vowels and consonants by different kinds of strokes (e.g., Arends' system for German or Melin's Swedish Shorthand where vowels are expressed by upward or sideway strokes and consonants and consonant clusters by downward strokes).

- Abjad – No expression of the individual vowels at all except for indications of an initial or final vowel (e.g., Taylor).

- Marked abjad – Expression of vowels by the use of detached signs (such as dots, ticks, and other marks) written around the consonant signs.

- Positional abjad – Expression of an initial vowel by the height of the word in relation to the line, no necessary expression of subsequent vowels (e.g., Pitman, which can optionally express other vowels by detached diacritics).

- Abugida – Expression of a vowel by the shape of a stroke, with the consonant indicated by orientation (e.g., Boyd).

- Mixed abugida – Expression of the vowels by the width of the joining stroke that leads to the following consonant sign, the height of the following consonant sign in relation to the preceding one, and the line pressure of the following consonant sign (e.g., most German shorthand systems).

Machine shorthand systems

[edit]Traditional shorthand systems are written on paper with a stenographic pencil or a stenographic pen. Some consider that only handwritten systems can strictly speaking be called shorthand.

Machine shorthand is also a common term for writing produced by a stenotype, a specialized keyboard. These are often used for court room transcripts and in live subtitling. However, there are other shorthand machines used worldwide, including: Velotype; Palantype in the UK; Grandjean Stenotype, used extensively in France and French-speaking countries; Michela Stenotype, used extensively in Italy; and Stenokey, used in Bulgaria and elsewhere.

Common modern English shorthand systems

[edit]One of the most widely used forms of shorthand is still the Pitman shorthand method described above, which has been adapted for 15 languages.[30] Although Pitman's method was extremely popular at first and is still commonly used, especially in the UK, in the U.S., its popularity has been largely superseded by Gregg shorthand, developed by John Robert Gregg in 1888.

In the UK, the spelling-based (rather than phonetic) Teeline shorthand is now more commonly taught and used than Pitman, and Teeline is the recommended system of the National Council for the Training of Journalists with an overall speed of 100 words per minute necessary for certification. Other less commonly used systems in the UK are Pitman 2000, PitmanScript, Speedwriting, and Gregg. Teeline is also the most common shorthand method taught to New Zealand journalists, whose certification typically requires a shorthand speed of at least 80 words per minute.

In Nigeria, shorthand is still taught in higher institutions of learning, especially for students studying Office Technology Management and Business Education[needs update].

Notable shorthand systems

[edit]- Chandler shorthand (Mary Chandler Atherton)[31]

- Current Shorthand (Henry Sweet)[32]

- Duployan shorthand (Émile Duployé)[33]

- Eclectic shorthand (J.G. Cross)[34]

- Gabelsberger shorthand (Franz Xaver Gabelsberger)[35]

- Deutsche Einheitskurzschrift[36] (German Unified Shorthand), which is based on the ideas of systems by Gabelsberger, Stolze, Faulmann, and other German system inventors

- Gregg shorthand (John Robert Gregg)[37]

- Munson Shorthand (James Eugene Munson)[38]

- Personal Shorthand, originally called Briefhand[39]

- Pitman shorthand (Isaac Pitman)[40]

- Speedwriting (Emma Dearborn)[41]

- Teeline Shorthand (James Hill)[42]

- Tironian notes (Marcus Tullius Tiro)[43]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ McCay, Kelly Minot. " All the World Writes Short Hand": The Phenomenon of Shorthand in Seventeenth-Century England." Book History 24, no. 1 (2021): 1-36.

- ^ Pepys, Samuel; Latham, Robert; Matthews, William (1970), The diary of Samuel Pepys: a new and complete transcription, Bell & Hyman, ISBN 978-0-7135-1551-0, Volume I, pp. xlvii–liv (for Thomas Shelton's shorthand system and Pepys' use of it)

- ^ Norman, Jeremy M, "The acropolis stone, the earliest example of shorthand", History of information, retrieved 24 October 2023

- ^ "Apprenticeship to a Shorthand Writer". Papyri. Retrieved 2021-12-07.

- ^ su_yi168,阿原. "(原创)漢語速記的發展及三個高潮的出現 - 阿原的日志 - 网易博客". 163.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ 中国速记的发展简史 Archived 2009-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ 迎接中国速记110年(颜廷超) Archived December 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "教授弋乂_新浪博客". sina.com.cn. Archived from the original on 2016-02-08.

- ^ Richard S. Westfall (1963), "Short-Writing and the State of Newton's Conscience, 1662", Notes and records of the Royal Society, Volume 18, Issue 1, Royal Society, pp. 10–16

- ^ McKenzie, Andrea. "Secret Writing and the Popish Plot: Deciphering the Shorthand of Sir George Treby." Huntington Library Quarterly 84, no. 4 (2021): 783-824.

- ^ "New World's Record for Shorthand Speed" (PDF). The new York times. December 30, 1922. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-09-26.

- ^ "Guide to the John Robert Gregg Papers" (PDF). Manuscripts and Archives Division. New York Public Library. 27 July 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2011.

- ^ "Script phonography". Archived from the original on 2016-03-06 – via Archive.

- ^ Graham, Andrew J., ed. (1854). "The Cosmotype". The Cosmotype. 1. Archived from the original on 2022-11-09. Retrieved 2022-11-08.

- ^ Graham, Andrew J. (ed.). The Cosmotype: devoted to that which will entertain usefully, instruct, and improve humanity. New York – via NYPL.

- ^ a b c Westby-Gibson, John (1887). The Bibliography of Shorthand. London: I. Pitman & Sons – via World catalogue.

- ^ Sexton, Chandler (1916). Graham's Business Shorthand. An Arrangement of Graham's Standard or American Phonography for High and Commercial Schools. New York: Andrew J. Graham & Co.

- ^ Jackson, James O. (January 21, 1974). "Presidential Papers Snarl Began in 1797". The Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "People". Time Magazine. February 8, 1960.

- ^ "Books", Pitman Shorthand, Homestead, archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ Kaneko, Tsuguo (2009-08-16). "Shorthand Education in Japan - 47th Intersteno Congress, Beijing 2009" (PPT). Archived from the original on 2023-02-10.

- ^ Housiki, Okoshi Yasu, archived from the original on 2016-03-03.

- ^ "速記文字文例". Okoshi-yasu. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.

- ^ Sokkidou, JP: OCN, archived from the original on 2013-05-22.

- ^ Sokkidou, OCN, p. 60, archived from the original on 2013-05-22

- ^ Steno, Nifty, archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- ^ Miller, J. Scott (1994), "Japanese Shorthand and Sokkibon", Monumenta Nipponica, 49 (4), Sophia University: 471–87, doi:10.2307/2385259, JSTOR 2385259, p. 473 for the origins of modern Japanese shorthand.

- ^ Miller 1994, pp. 471–87.

- ^ Anderson, Van (2010-09-24). "Proposal to include Duployan script and Shorthand Format Controls in UCS" (PDF). ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2. Retrieved 2024-06-25.

- ^ "The Joy of Pitman Shorthand". pitmanshorthand.homestead.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-15.

- ^ Howe, Julia Ward; Graves, Mary Hannah (1904). "MARY ALDERSON ATHERTON". Sketches of Representative Women of New England. New England Historical Publishing Company. pp. 416–18.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Sweet, Henry (1892), A manual of current shorthand orthographic and phonetic by Henry Sweet, Clarendon, OCLC 250138117

- ^ Perrault, Denis R; Duploye, Emile; Gueguen, Jean Pierre; Pilling, James Constantine, La sténographie Duployé adaptée aux langues des sauvages de la Baie d'Hudson, des Postes Moose Factory, de New Post, d'Albany, de Waswanipi & de Mékiskan, Amérique du Nord / [between 1889 and 1895] (in French), OCLC 35787900

- ^ Cross, J G (1879), Cross's eclectic short-hand: a new system, adapted both to general use and to verbatim reporting, Chicago, S.C. Griggs and Co. [1878], OCLC 2510784

- ^ Geiger, Alfred (1860), Stenography, or, Universal European shorthand (on Gabelsberger's principles) : as already introduced in Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Russia, Greece, Italy &c, Dresden, OCLC 41010411

- ^ Czerny, Karl (1925), Umlernbuch auf die deutsche Einheitskurzschrift : Für Gabelsbergersche Stenographen (in German), Eigenverl, OCLC 72106122

- ^ Gregg, John Robert; Power, Pearl A (1901), Gregg shorthand dictionary, Gregg Pub. Co, OCLC 23108068

- ^ Munson, James Eugene (1880), Munson's system of phonography. The phrase-book of practical phonography, containing a list of useful phrases, printed in phonographic outlines; a complete and thorough treatise on the art of phraseography ... etc, New York, J.E. Munson, OCLC 51625624

- ^ Salser, Carl Walter; Yerian, C Theo (1968), Personal shorthand, National Book Co, OCLC 11720787

- ^ Isaac Pitman (1937), Pitman shorthand, Toronto, OCLC 35119343

- ^ Dearborn, Emma B (1927), Speedwriting, the natural shorthand, Brief English systems, inc., OCLC 4791648

- ^ Hill, James (1968), Teeline: a method of fast writing, London, Heinemann Educational, OCLC 112342

- ^ Mitzschke, Paul Gottfried; Lipsius, Justus; Heffley, Norman P (1882), Biography of the father of stenography, Marcus Tullius Tiro. Together with the Latin letter, "De notis," concerning the origin of shorthand, Brooklyn, N.Y, OCLC 11943552

External links

[edit]- Keyscript Shorthand: keyscriptshorthand

.com & keyscriptshorthand2.website3 .me  Media related to Shorthand at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shorthand at Wikimedia Commons The dictionary definition of shorthand at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of shorthand at Wiktionary- The Louis A. Leslie Collection of Historical Shorthand Materials at Rider University – materials for download

Shorthand

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition

Shorthand, also known as stenography, is a method of rapid writing that employs symbols, abbreviations, or characters to substitute for letters, sounds, words, or phrases, thereby enabling significantly faster transcription than traditional longhand.[6] This approach prioritizes efficiency in capturing spoken language, making it particularly useful for applications such as court reporting, journalistic note-taking, and secretarial documentation.[7] By reducing the number of strokes and eliminating unnecessary elements, shorthand systems can achieve writing speeds of 100 to 225 words per minute, far exceeding the average longhand rate of 20 to 30 words per minute.[8] Many shorthand systems rely on phonetic principles, where symbols represent the sounds of speech rather than conventional spelling, allowing writers to approximate pronunciation for brevity; others use alphabetic approaches with modified letters.[7] Many systems omit vowels entirely or indicate them optionally through positioning or diacritical marks, focusing instead on consonants to form the structural outline of words, as vowels are often recoverable from context.[8] This foundation distinguishes shorthand from alphabetic writing, promoting fluidity and minimalism while maintaining legibility when transcribed back to full text. Common techniques include brief forms for frequently used words, blending of outlines for compounds, and the use of prefixes or suffixes to modify meanings without separate notation.[9] Shorthand systems are diverse, encompassing geometric styles with straight lines and curves versus script-like forms resembling cursive, but all share the goal of balancing speed, accuracy, and ease of learning.[7] Historically developed to meet the demands of real-time recording, these methods have evolved from ancient tachygraphy to modern adaptations, though their prominence has waned with digital recording technologies.[7] Despite this, shorthand remains a valuable skill for professionals requiring concise, manual documentation in low-tech environments.[6]Basic Principles

Shorthand systems are designed to enable rapid transcription of spoken language by representing sounds, words, and phrases through simplified symbols rather than full orthographic spelling.[9] Many employ a phonetic approach that prioritizes the natural flow of speech over conventional letter forms, allowing writers to capture up to 200 words per minute or more in proficient use.[10] A core principle is the simplification of the writing alphabet, achieved by reducing the number of distinct characters—often to 20-40 symbols—or by modifying existing letters into abbreviated curves and lines that align with hand movements.[9] Curvilinear strokes, based on ellipses or ovals, facilitate smooth, continuous motion, as straight lines or sharp angles increase effort and slow the process compared to fluid curves.[10] Vowels are frequently omitted or indicated minimally (e.g., via dots or positions) to minimize strokes, since context and consonants often suffice for decoding, though inclusion enhances legibility in ambiguous cases.[9][10] Efficiency in shorthand relies on joining elements into single-word outlines for common terms, reducing the average strokes per word to one or fewer lifts of the pen, which directly correlates with higher writing speeds.[11] High-frequency words receive brief, dedicated symbols, while rarer ones use phonetic combinations or abbreviations, ensuring that 80-90% of everyday language can be notated with minimal movements.[11] Variations in stroke attributes—such as thickness (light vs. shaded), length, slope, or position relative to the baseline—convey distinctions like voiced/unvoiced sounds or grammatical nuances without additional characters.[9][10] Overall, these principles balance speed and readability by favoring horizontal, light-line writing that mimics longhand's natural slope, avoiding downward or shaded strokes that disrupt flow.[10] Systems emphasize complete representation for clarity, particularly for homonyms, while optimizing for frequent elements to achieve practical utility in real-time transcription.[11]History

Ancient and Classical Origins

The origins of shorthand systems trace back to ancient civilizations where the need for rapid writing emerged in administrative, legal, and literary contexts. In ancient Egypt, the hieratic script developed as a cursive and abbreviated form of hieroglyphs, enabling scribes to write more quickly than with the formal monumental script.[12] This system, used from the First Dynasty around 2925 BCE until about 200 BCE, was primarily employed for religious, literary, and administrative documents on papyrus with ink and brush.[13] Later, the demotic script evolved as an even more streamlined cursive variant of hieratic, incorporating ligatures and abbreviations to further accelerate writing, particularly for everyday legal and business records from the 7th century BCE to the 5th century CE.[14] These scripts prioritized speed and practicality over pictorial detail, laying foundational principles for later shorthand by reducing complex symbols into fluid, interconnected forms.[15] In ancient Greece, stenography, known as tachygraphy, began to take shape during the Hellenistic period, with evidence from the 4th century CE papyri suggesting earlier roots in the 1st century BCE for systematic abbreviation.[16] A key artifact is the Montserrat papyrus codex (P. Monts. Roca inv. nos. 166r-178v), a 4th-century word-list of over 2,300 unaccented Greek terms, which served as a manual for stenographic training and linked to earlier syllabaries documented in the 20th century.[17] This system used abbreviated signs for words and syllables, facilitating the transcription of speeches, legal proceedings, and philosophical texts, often by enslaved scribes in bureaucratic settings.[16] Greek tachygraphy influenced administrative record-keeping across the Mediterranean, with parallels to secret writing practices under oppressive regimes, and its signs appeared in papyri from sites like Antinoopolis.[17] Roman shorthand reached a sophisticated level with the Tironian notes (notae Tironianae), attributed to Marcus Tullius Tiro, a freedman and secretary to Cicero, developed in the late Roman Republic around 63 BCE.[18] The system comprised initially about 4,000 symbols—later expanding to 13,000—that abbreviated words, syllables, or phrases using modified letters, dots, and commas for inflections, allowing notaries to capture Senate debates, public speeches, and court proceedings verbatim on wax tablets or papyrus.[18] Earlier precursors included the vulgares notae credited to the poet Ennius in the 2nd century BCE, with around 1,100 signs for general use, as noted by Quintilian.[19] Tironian notes became essential for Roman bureaucracy and literature, enabling the rapid documentation of Cicero's extensive correspondence and orations, and persisted into Late Antiquity for imperial and ecclesiastical purposes before revival in the medieval era.Developments in Asia

In ancient China, during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), early forms of rapid writing emerged that served as precursors to modern shorthand. These included xingshu (running script), a fluid and connected style of standard script designed for speed, and caoshu (grass script or cursive script), which abbreviated and stylized characters to enable quicker notation, particularly for official records and correspondence.[20] These scripts allowed scribes to write more efficiently than the formal lishu (clerical script), laying foundational principles for abbreviation in East Asian writing systems. The introduction of phonetic shorthand in China occurred in the late 19th century amid efforts to modernize documentation for diplomacy and governance. In 1896, Cai Xiyong, a Chinese diplomat educated in Western languages, developed Chuanyin kuaizi (Phonetic Shorthand), the first modern Chinese shorthand system. Inspired by Isaac Pitman's English shorthand, it used 36 consonants and 12 vowels to phonetically represent Mandarin sounds, with symbols written consecutively for efficiency, addressing the challenges of recording speech in a logographic language.[21] Cai's system was refined by his son, Cai Zhang, in 1912, incorporating improvements for parliamentary reporting and reducing the need for character memorization among illiterate users.[22] Subsequent innovations in the early 20th century expanded Chinese shorthand's applicability. Wan Yi's Zhongguo Xinshi Sujishu (1919) introduced a simplified phonetic approach tailored to regional dialects, while Tang Yawei's AI Suji (1938) emphasized single-stroke characters for even faster transcription.[22] Zhang Zhaoyun's system (1935) and Yan Tingchao's cursive-based method (1951) further integrated elements of traditional calligraphy, achieving speeds of up to 200 characters per minute for court and journalistic use. These developments were documented in Tan Yawei et al.'s Hundred Years of Chinese Shorthand (2000), highlighting shorthand's role in national literacy and administrative reform.[22] By the mid-20th century, systems like Kim Zhangfeng's single-stroke method (1944) standardized shorthand for official proceedings, influencing over 100 variants used in China today.[22] In Korea, shorthand development paralleled Chinese influences but adapted to Hangul's phonetic structure. Early 20th-century systems drew from Japanese models, with the National Assembly adopting a dedicated shorthand training program in 1969, training 217 reporters by 1973 for legislative transcription.[22] Om Seyon developed a cursive Hangul shorthand system in 1954, abbreviating syllables for rapid note-taking, achieving compatibility with Korea's alphabetic script while supporting speeds comparable to Western stenography.[22] In India, shorthand arrived via British colonial administration in the 19th century, with no evidence of indigenous ancient systems akin to those in China. By the early 20th century, Pitman shorthand dominated, training thousands for government roles, though it remained an imported tool rather than a native evolution.[23]Evolution in Europe and North America

The evolution of shorthand in Europe began with the revival of ancient Roman systems during the Renaissance. Tironian notes, originally developed by Marcus Tullius Tiro around 63 BC for recording Cicero's speeches, were rediscovered and adapted by scholars like Lorenzo di Jacopo de' Rustici in the late 15th century, who used them to transcribe sermons by Girolamo Savonarola.[24] By the 16th century, English innovator Timothy Bright published Characterie in 1588, the first dedicated shorthand system for English, employing a complex array of symbols to represent syllables and words for efficient note-taking in sermons and legal proceedings.[25] This marked a shift toward vernacular adaptations, with subsequent systems like John Willis's An Stenographie (1602) introducing alphabetical elements, and Thomas Shelton's Tachygraphy (1626) gaining popularity among Puritans for its simplicity in capturing religious discourse. It was famously employed by Samuel Pepys in the 1660s to record his private diaries, which were kept secret through shorthand and later deciphered and published.[24][26] The 18th century saw further refinements amid growing demand for accurate reporting in parliaments and courts. John Byrom's system, patented in 1742 but kept private until after his death, emphasized curved strokes for phonetic representation and influenced later developers.[24] In 1786, Thomas Gurney adapted shorthand for verbatim court reporting in England, establishing its professional utility. The 19th century brought phonetic breakthroughs: Franz Xaver von Gabelsberger's 1834 German system used cursive forms to denote sounds, becoming a model across Europe, while Stolze's competing 1841 method focused on word stems for northern German adoption.[24] Sir Isaac Pitman's Stenographic Sound-Hand (1837) revolutionized English shorthand with its geometric strokes representing consonants and positional notation for vowels, achieving widespread use in Britain for journalism, education, and personal diaries by the mid-1800s.[27] In France, Émile Duployé's 1867 adaptation of earlier Taylor-inspired systems prioritized legibility and speed, remaining influential in clerical work.[24] Shorthand's introduction to North America occurred in the early 17th century, with colonists like John Pynchon employing rudimentary forms to record sermons in Massachusetts around 1637–1639.[24] Systematic adoption accelerated in the 19th century when Benn Pitman, Isaac's brother, immigrated in 1852 and established the Phonographic Institute in Cincinnati, adapting the Pitman system with modifications for American English pronunciation and promoting it through schools and court reporting training.[27] By the 1860s, shorthand entered U.S. courtrooms, with congressional reporters hired by 1873, solidifying its role in legal transcription.[25] John Robert Gregg's 1888 system, developed in Ireland but refined after his 1893 move to the United States, introduced light-line phonography with elliptical forms for greater speed and cursive flow, quickly surpassing Pitman in popularity due to its adaptability for business and journalism.[27] Gregg's iterations, including the 1916 Pre-Anniversary edition, dominated North American education and professional use into the 20th century, with over 70% of U.S. stenographers trained in it by the 1920s.[28] In the 20th century, North American innovations focused on mechanization and efficiency. The 1879 invention of the first shorthand typewriter evolved into keyboard-based stenotype machines by the 1910s, with the Ireland machine (1911) standardizing layouts for court reporters.[25] By the 1940s, these devices largely replaced manual shorthand in high-speed environments like legislatures, integrating paper tapes with later computer interfaces, though manual systems like Gregg persisted in education until voice recognition technologies diminished their overall use by the late 20th century.[25] Indigenous adaptations, such as Sequoyah's 1821 Cherokee syllabary—influenced by shorthand principles—and Father Jean-Marie LeJeune's teaching of Duployan to First Nations communities around 1900, highlighted localized evolutions.[24]Shorthand in Japan

Shorthand, known as sokki (速記) in Japanese, emerged in the modern era during the Meiji period, primarily influenced by Western systems to meet the demands of rapid documentation in an era of political and social transformation. The term sokki was coined in 1884 by Fumio Yano, drawing from Chinese characters meaning "quick writing," and it quickly became the standard nomenclature across East Asia, including Japan, Korea, and China.[22] Early development was spurred by the need to record parliamentary debates following the establishment of the Imperial Diet in 1890, as well as to transcribe oral storytelling and journalistic reports.[29] The foundational system was created by Takusari Koki (1854–1938), often called the "Lightning Pen General," who published Nihon bōchō hikkihō (Japanese Court Reporting Method) in 1882 after encountering Western shorthand in journals like Popular Educator. Takusari's method adapted phonetic principles from American systems such as Graham and Pitman, using geometric lines and curves to represent syllables, aligning with Japanese's syllabic structure rather than alphabetic consonants. This innovation enabled the first stenographic recordings of political speeches and rakugo storytelling, leading to the publication of sokkibon—inexpensive shorthand-transcribed books that popularized vernacular literature and sold hundreds of thousands of copies by the mid-1880s.[22][30] Subsequent systems built on Takusari's foundation, incorporating eclectic elements from Gregg, Cross, and Lindsley methods to enhance speed and simplicity. Notable developments include Edward Gauntlet's 1899 eclectic shorthand, which influenced later variants like Kumasaki (1906) and Waseda (1930); Takeda's 1905 single-stroke theory; Masachika Nakane's 1914 practical single-stroke system, still taught in schools like Gifu Prefectural Commercial High School; and Masakatsu Kotani's system, which applied a "same vowel, same direction" rule inspired by Gregg. By the early 20th century, over a hundred sokki variants existed, with ten authorized for official use, including Ishimura, Iwamura, and Yamane. These systems emphasized simplified lines and phonetic representation, achieving writing speeds up to 300 syllables per minute for proficient users.[22] In practice, sokki profoundly impacted journalism and governance, allowing verbatim reporting of Diet proceedings via specialized systems like Shugiin for the House of Representatives, which uses highly abbreviated lines for efficiency. It also facilitated the genbun'itchi movement, bridging spoken and written Japanese by capturing colloquial speech in literature and news. However, by the late 20th century, electronic recording technologies largely supplanted manual sokki, reducing its widespread training and practitioners. Today, it persists in niche applications, such as parliamentary stenography, national speed-writing contests, and limited educational programs, preserving a legacy of adapting foreign innovations to Japan's linguistic uniqueness.[22][30]Classification of Shorthand Systems

Geometric Systems

Geometric shorthand systems represent one of the primary classifications of stenographic methods, characterized by the use of abstract symbols composed primarily of straight lines, angles, circles, and other basic geometric forms to denote phonetic elements such as consonants and syllables. These systems prioritize brevity and speed by abstracting away from the curves of longhand script, often omitting or minimally indicating vowels to facilitate rapid writing. Unlike script-like systems that mimic cursive handwriting, geometric approaches rely on precise, diagrammatic characters that can be joined or disconnected for efficiency.[31] The origins of geometric shorthand trace back to ancient innovations, with Marcus Tullius Tiro's Tironian notes around 63 BCE serving as an early precursor, employing abbreviated Latin symbols including geometric-like marks for common words and phrases; this system endured for over a millennium in Europe before fading in the Middle Ages. A revival occurred during the Renaissance, notably with Timothy Bright's 1588 Characterie, which utilized straight lines and semicircles to represent sounds in an alphabetic framework. The modern era of geometric systems began in the late 18th century, as inventors sought phonetic accuracy and mechanical simplicity in response to growing demands for verbatim reporting in parliaments and courts.[24][31] Samuel Taylor's Universal Stenography (1786) marked a pivotal advancement, introducing a geometric alphabet of 19 simplified characters—primarily verticals, horizontals, and curves—that could be joined for common diphthongs and omitted vowels for speed; this system gained widespread adoption in Britain and was adapted into languages like French, Dutch, and Portuguese by the early 19th century. Building directly on Taylor's work, which he studied in 1829, Isaac Pitman published Stenographic Soundhand in 1837 (later renamed Phonography), a fully phonetic geometric method using angled strokes (e.g., 45-degree lines for 'p' and 'b') differentiated by thickness or shading to distinguish voiced and unvoiced sounds, with vowels as optional dots or dashes. Pitman's system revolutionized stenography, becoming the dominant method in the UK for court reporting and commerce, and influencing global adaptations due to its logical, sound-based structure.[31][32] Other notable geometric systems include the Sloan-Duployan shorthand (1882 English adaptation of Émile Duployé's French method), which employed printed-like geometric ticks and loops for extreme brevity, achieving speeds up to 300 words per minute in competitions and holding the U.S. Shorthand Speed Championship for over a decade. These systems generally excel in legibility when written clearly but require practice for fluid execution, contrasting with later cursive innovations like Gregg shorthand (1888), which shifted toward elliptical curves for easier wrist motion. By the early 20th century, nearly 500 English shorthand systems had been proposed, though Pitman and Taylor remained the most influential for their balance of simplicity and phonetic fidelity.[31]Script-Like Systems

Script-like shorthand systems, also known as cursive or stenographic shorthands, are designed to mimic the fluid motions and forms of ordinary handwriting while incorporating abbreviations and simplifications to increase writing speed. Unlike geometric systems that rely on abstract lines, circles, and angles, script-like systems use modified versions of alphabetic letters, often based on ellipses, loops, and cursive strokes derived from longhand. This approach allows for greater legibility and ease of learning, as it builds on familiar writing habits, though it may sacrifice some speed compared to purely symbolic methods.[33][34] The foundational script-like system was developed by Franz Xaver Gabelsberger in 1817, with its textbook published in 1834 as Anleitung zur deutschen Kürzschreibkunst. Gabelsberger's method, known as "Speech-sign art," adapted Latin longhand characters into abbreviated forms, emphasizing neat outlines and phonetic representation for German speech. It became widely influential in Europe, spawning numerous adaptations and serving as a model for later systems that prioritized readability alongside rapidity.[35][36] In English-language contexts, Speedwriting emerged in 1924, invented by Emma Dearborn, an instructor at the University of Chicago. This system employs standard letters and punctuation to phonetically spell words, omitting silent letters and short vowels while expressing long vowels explicitly; for instance, "cat" is written as "kat" but "cake" as "kāk." It resembles cursive handwriting, enabling users to write at speeds up to 70-80 words per minute after brief training, and was marketed for its simplicity and compatibility with typing.[37][38] Forkner Shorthand, published in 1952 by Hamden L. Forkner, further refined the alphabetic script-like approach by using simplified longhand letter forms spelled phonetically, with about 80% of outlines derived from cursive writing. It eliminates separate symbols for most vowels, blending them into consonant strokes, and includes brief forms for common words to achieve speeds of 100-120 words per minute. Studies highlight its rapid skill acquisition due to its reliance on existing handwriting knowledge, making it suitable for business and secretarial training.[39] Teeline Shorthand, created in 1968 by James Hill, a shorthand expert from Liverpool, represents a modern hybrid within this category. It streamlines the English alphabet by removing unnecessary loops and tails—such as eliminating the downward stroke in 'g' or 'y'—and uses positional rules and disjoined letters for vowels and blends. Written in a continuous cursive style, Teeline achieves transcription speeds of 100-140 words per minute and is particularly popular among journalists and in the UK for its quick learning curve, often mastered in weeks.[9][40] These systems prioritize accessibility and transcription ease over maximal velocity, often integrating with longhand for mixed use, and have influenced contemporary note-taking practices despite the rise of digital alternatives.[1]Vowel Indication Methods

In shorthand systems, vowels pose a challenge due to the need for writing speed, leading to various methods of indication that balance brevity with readability. These methods evolved from early positional techniques to more integrated representations in modern systems, often prioritizing consonant skeletons while using contextual cues or minimal marks for vowels.[7] One primary approach is positional writing, where the placement of consonant strokes relative to a baseline determines the vowel sound, minimizing additional symbols. In early English systems like Thomas Shelton's Tachygraphy (1636), vowels are indicated by the position of symbols: for instance, placing a "g" above a "b" represents "bag," while below it signifies "bug." This method relies on geometric positioning for brevity, with explicit vowel symbols used only at word beginnings or for consecutive vowels. Similarly, William Rich's Semography (1697) employs positional cues, augmenting them with a loop for the letter "e," though vowels are largely omitted elsewhere to favor speed.[41] Diacritical marks represent another common method, using small attachments like dots, dashes, or hooks placed adjacent to consonant strokes to denote vowels without interrupting flow. In Isaac Pitman's system (1837), short vowels are shown as light dots or dashes, while long vowels use heavy (thickened) versions, positioned in first (near stroke start), second (mid-stroke), or third (near end) places to specify sounds. For example, a light dot before a "p" stroke indicates the short "e" in "pen," and diphthongs like "oi" are marked with small circles. This disjoined approach allows precise phonetic representation but requires consistent placement for transcription.[42] In contrast, joined or integrated vowel representation embeds vowels directly into the consonantal outline, often using curves or loops for a fluid, cursive style. John Robert Gregg's system (1888) groups vowels phonetically and marks them with circles, hooks, or loops joined to strokes, avoiding separate positions or shading. The small circle denotes sounds like "a" (as in "at"), unmarked for short or accented for long, while a large upward hook represents "u" sounds (as in "tuck"). Diphthongs, such as "ow" in "now," blend naturally without special marks, relying on outline context for disambiguation. This method enhances legibility at high speeds compared to disjoined systems.[43] Some systems further simplify by omitting vowels entirely or using abbreviated forms, depending on reader familiarity and context. In geometric systems like Taylor shorthand (1786), minimal or no vowel marks lead to ambiguities—e.g., a single symbol might represent "ever," "over," or "offer"—resolved through word boundaries or prior knowledge. Alphabetic systems treat vowels like consonants with full signs, but this is rarer in efficient shorthands due to reduced speed. Across methods, vowel indication often adapts to phonetic standards, such as Received Pronunciation in Pitman, with regional variations noted in practice.[7]| Method | Key Features | Example Systems | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positional Writing | Stroke placement above/below/on line indicates vowel | Shelton (1636), Rich (1697) | Minimal symbols; fast | Ambiguity without context; limited to simple positions |

| Diacritical Marks | Dots/dashes/hooks adjacent to strokes; light/heavy for short/long | Pitman (1837) | Precise phonetic detail | Requires accurate placement; slower if overused |

| Joined/Integrated | Curves/loops blended into outline; phonetic grouping | Gregg (1888) | Fluid motion; readable | Relies on outline familiarity; potential homophone confusion |

| Omission/Abbreviation | No marks; context-based | Taylor (1786) | Maximum speed | High ambiguity; needs expert reader |

Machine-Based Systems

Machine-based shorthand systems represent a significant evolution from manual pen-and-paper methods, employing mechanical or electronic devices to capture speech at high speeds through chorded keyboards that input phonetic, syllabic, or orthographic representations of words. These systems typically allow users to press multiple keys simultaneously—known as chording—to produce syllables or entire words, achieving transcription rates of 180 to 350 words per minute with high accuracy. Unlike traditional shorthand, which relies on abbreviated symbols written by hand, machine systems produce printed or digital output directly, reducing translation time and errors. The development of these machines addressed the limitations of manual shorthand in demanding environments like courtrooms and conferences, where verbatim recording is essential.[44][45][46] The origins of machine-based shorthand trace back to the late 19th century, driven by the need for faster, more reliable transcription amid growing demands for legal and journalistic reporting. In 1877, American court reporter Miles Bartholomew invented the first successful shorthand machine, a device with ten keys that generated dots and dashes similar to Morse code, allowing sequential input to form phonetic outlines. Patented in 1879 and 1884, Bartholomew's machine was manufactured by the United States Stenograph Corporation and remained in use until 1937, marking the transition from manual to mechanical systems. Building on this, in 1889, George Kerr Anderson developed a shorthand typewriter with a keyboard permitting simultaneous key presses to produce English characters, which was notably used to report President William McKinley's inaugural address. These early inventions laid the groundwork for chorded input, emphasizing efficiency over full alphabetic typing.[44] A pivotal advancement occurred in the early 20th century with the introduction of phonetic chord keyboards. In 1911, Ward Stone Ireland patented the Stenotype machine, a lightweight (11.5 pounds) device featuring a depressible keyboard arranged to follow English phonetics, with consonants on the outer keys and vowels in the center. This allowed chording up to 22 keys to capture syllables or words in a single stroke, achieving 99.3% accuracy in a 1914 National Shorthand Reporters' Association contest. The Stenotype quickly became the standard for court reporting in the United States, evolving into models like the 1914 Master Model (weighing 6 pounds) and the 1927 LaSalle Stenotype. By the 1960s, electronic versions emerged, such as the 1963 STENOGRAPH Data Writer, which encoded notes on magnetic tape for computer-aided transcription (CAT), integrating shorthand with digital processing. Today, modern Stenograph machines connect to computers via USB, using software to translate chords into readable text in real-time, supporting speeds up to 350 words per minute.[44][47][44] Parallel developments occurred in Europe, yielding alternative systems tailored to local languages and needs. The Palantype, designed around 1939 and produced from 1955 to 1965 in England, was patented by an English inventor named Fairbanks and based on the earlier French Grandjean machine (1910). Named after Mademoiselle Palanque, a French teacher who introduced machine shorthand to Britain, the Palantype featured a phonetic keyboard with up to eight keys for simultaneous pressing, recording syllabic text onto a paper roll at 180-200 words per minute. It excelled in distinguishing homophones and was used for verbatim reporting in UK courts and broadcasting, though it saw less adoption than the Stenotype due to its complexity. Adapted for CAT in later versions, the Palantype incorporated a 70,000-word lexicon for automated translation.[45][45] Another notable system is the Velotype, a Dutch innovation originating from linguistic research in the mid-20th century and commercialized in the 1970s. Invented by Nico Berkelmans and Marius Tutein Nolthenius, the Velotype employs an ergonomic, chorded computer keyboard with an orthographic layout, where users press multiple keys to input syllables or words directly, bypassing individual letters. Early mechanical versions evolved into electronic models by 1982, with further refinements in 2001 for computer integration. This system prioritizes speed and reduced finger movement, enabling typing rates comparable to stenotype while being more accessible for non-specialists, and it has found applications in live captioning and multilingual transcription.[46][48]| System | Inventor(s) | Year Introduced | Key Features | Primary Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartholomew Machine | Miles Bartholomew | 1877 | Ten keys for Morse-like dots/dashes; sequential phonetic input. | Early court reporting. |

| Anderson Typewriter | George Kerr Anderson | 1889 | Keyboard for simultaneous presses; outputs English characters. | Journalistic transcription. |

| Stenotype | Ward Stone Ireland | 1911 | 22-key phonetic chorded keyboard; up to 350 wpm with CAT integration. | U.S. legal and conference. |

| Palantype | Fairbanks (based on Grandjean) | 1939 (design) | 8-key phonetic/syllabic chording; paper roll output, 180-200 wpm. | UK/European verbatim reporting. |

| Velotype | Nico Berkelmans, Marius Tutein Nolthenius | 1970s | Orthographic chorded keyboard for syllables/words; ergonomic computer input. | Live captioning, general typing. |