Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

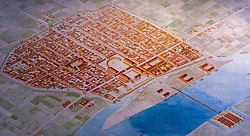

Insula (Roman city)

View on Wikipedia

The Latin word insula (lit. 'island'; pl.: insulae) was used in Roman cities to mean either a city block in a city plan (i.e. a building area surrounded by four streets)[1] or later a type of apartment building that occupied such a city block specifically in Rome and nearby Ostia.[2][3] The latter type of Insulae were known to be prone to fire and rife with disease.[4]

A standard Roman city plan[5] was based on a grid of orthogonal (laid out on right angles) streets.[6] It was founded on ancient Greek city models, described by Hippodamus. It was used especially when new cities were established, e.g. in Roman coloniae.

The streets of each city were designated the decumani (east–west-oriented) and cardines (north–south). The principal streets, the decumanus maximus and cardo maximus, intersected at or close to the forum, around which the most important public buildings were sited.

References

[edit]- ^ Chaitanya Iyyer (1 December 2009). Land Management. Global India Publications. p. 147. ISBN 978-93-80228-48-8.

- ^ Gregory S. Aldrete (2004). Daily Life in the Roman City: Rome, Pompeii and Ostia. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 78–80. ISBN 978-0-313-33174-9.

- ^ Stephen L. Dyson (1 August 2010). Rome: A Living Portrait of an Ancient City. JHU Press. pp. 217–9. ISBN 978-1-4214-0101-0.

- ^ Goldsworthy, Adrian (28 August 2014). Augustus: First Emperor of Rome. Yale University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-300-21666-0.

- ^ Macaulay, David (1974). City: A Story of Roman Planning and Engineering. Boston: Houghton-Mifflin.

- ^ "Roman Engineers: A Plan for a Small Roman City".

Sources and further reading

[edit]- The Insula IX Excavation: http://www.reading.ac.uk/silchester/town-life/insula_ix.php link broken

- Pompeii Insula 9: http://donovanimages.co.nz/proxima-veritati/insula-9/index.html