Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

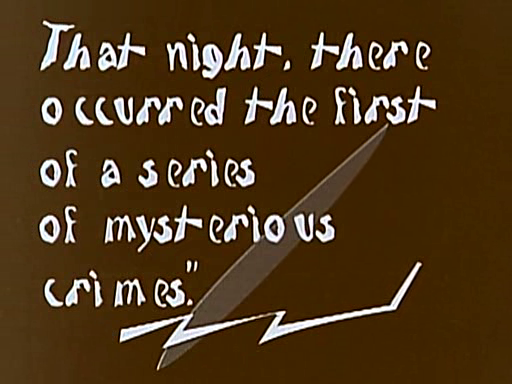

Intertitle

View on Wikipedia

In films and videos, an intertitle, also known as a title card, is a piece of filmed, printed text edited into the midst of (hence, inter-) the photographed action at various points. Intertitles used to convey character dialogue are referred to as "dialogue intertitles", and those used to provide related descriptive/narrative material are referred to as "expository intertitles".[1] In modern usage, the terms refer to similar text and logo material inserted at or near the start or end of films and television shows.

Silent film era

[edit]In the silent film era, intertitles were mostly called "subtitles", but also "leaders", "captions", "titles", and "headings", prior to being named intertitles,[2] and often had Art Deco motifs. They were a mainstay of silent films once the films became of sufficient length and detail to necessitate dialogue or narration to make sense of the enacted or documented events. The British Film Catalogue credits the 1898 film Our New General Servant by Robert W. Paul as the first British film to use intertitles.[3] Film scholar Kamilla Elliott identifies another early use of intertitles in the 1901 British film Scrooge, or, Marley's Ghost.[4] The first Academy Awards presentation in 1929 included an award for "Best Writing – Title Cards" that went to Joseph W. Farnham for the films Fair Co-Ed; Laugh, Clown, Laugh; and Telling the World.[5] The award was never given again, as intertitles went out of common use due to the growing popularity of the "talkies".[6]

Modern use

[edit]In modern use, intertitles are used to supply an epigraph, such as a poem, or to distinguish various "acts" of a film or multimedia production by use as a title card. However, they are most commonly used as part of a historical drama's epilogue to explain what happened to the depicted characters and events after the conclusion of the story proper.

The development of the soundtrack slowly eliminated their utility as a narrative device (they were common for providing narration, but not dialogue, well into the 1930s), but they are occasionally still used as an artistic device. For instance, intertitles were used as a gimmick in Frasier. The BBC's drama Threads uses them to give location, date and information on distant events beyond Sheffield. Law & Order and its related spinoffs used them to give not only the location, but also the date of the upcoming scene. Guy Maddin is a modern filmmaker known for recreating the style of older films, and uses intertitles appropriately. Some locally produced shows, such as quiz bowl game shows, use animated variations of intertitles to introduce the next round. In the show Invincible the title card is used for comedic effect, such as interrupting a character with the title card whenever they say the titular protagonist's name, often exploited for comedic purposes such as one instance where a character is interrupted multiple times.

Amateur use

[edit]Intertitles have also had a long history in the area of amateur film. The efforts of home movie aficionados to intertitle their works post-production led to the development of a number of innovative approaches to the challenge. Frequently lacking access to high-quality film dubbing and splicing equipment, amateur film makers must plan ahead when making a film to allow space for filming an intertitle over the existing film. Intertitles may be printed neatly on a piece of paper, a card, or a piece of cardboard and filmed, or they may be formed from adhesive strips and affixed to glass. In the early 1980s, digital recording technology improved to the point where intertitles could be created in born-digital format and recorded directly onto the film. Several specialty accessories from this period such as Sony's HVT-2100 Titler and cameras such as Matsushita's Quasar VK-743 and Zenith VC-1800 could be used to generate intertitles for home movies.[7]: 20 Early 1980s video game consoles and applications catering to the demo scene were also adapted for the generation and recording of intertitles for home films. Among these were included the ColecoVision, the Magnavox Odyssey² (using programs such as the Type & Talk cartridge and the Voice module), the Bally Astrocade (using the built-in Scribbling program or the more advanced Creative Crayon cartridge), and the intertitle-specialized Famicom Titler.[7]: 21

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Chisholm, Brad (1987). Marsden, Michael T.; Nachbar, John G. (eds.). "Reading Intertitles". Journal of Popular Film & Television. 15 (3). Taylor & Francis: 137. doi:10.1080/01956051.1987.9944095. ISSN 0195-6051. LCCN 80640493. OCLC 746948137.

- ^ Nagels, Katherine (2012). "'Those funny subtitles': Silent film intertitles in exhibition and discourse". Early Popular Visual Culture. 10 (4): 367–382. doi:10.1080/17460654.2012.724570. ISSN 1746-0654. S2CID 194065623.

- ^ The British Film Catalogue, by Denis Gifford (Routledge, 2016), page 142.

- ^ Elliot, Kamilla (27 November 2003). Dickens on Screen. Cambridge University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-521-00124-3.

- ^ "The 1st Academy Awards (1929) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences. 8 October 2014. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- ^ "Best Title Writing". Awards and Shows. Retrieved 12 November 2012.

- ^ a b Woodcock, Roderick (May 1983). "The TV Den: Understanding Techniques and Technology". Video. Vol. 7, no. 2. Reese Communications. pp. 20–21. ISSN 0147-8907.