Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Bar (unit)

View on Wikipedia| bar | |

|---|---|

An aluminium cylinder of wall thickness 5 millimetres (0.20 in) after an external pressure of 700 bar was applied to it | |

| General information | |

| Unit system | metric system |

| Unit of | pressure |

| Symbol | bar |

| Conversions | |

| 1 bar in ... | ... is equal to ... |

| SI units | 100 kPa |

| CGS units | 106 Ba |

| US customary units | 14.50377 psi |

| Atmospheres | 0.986923 atm |

The bar is a metric unit of pressure defined as 100,000 Pa (100 kPa), though not part of the International System of Units (SI). A pressure of 1 bar is slightly less than the current average atmospheric pressure on Earth at sea level (approximately 1.013 bar).[1][2] By the barometric formula, 1 bar is roughly the atmospheric pressure on Earth at an altitude of 111 metres at 15 °C.

The bar and the millibar were introduced by the Norwegian meteorologist Vilhelm Bjerknes, who was a founder of the modern practice of weather forecasting, with the bar defined as one megadyne per square centimetre.[3]

The SI brochure, despite previously mentioning the bar,[4] now omits any mention of it.[1] The bar has been legally recognised in countries of the European Union since 2004.[2] The US National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) deprecates its use except for "limited use in meteorology" and lists it as one of several units that "must not be introduced in fields where they are not presently used".[5] The International Astronomical Union (IAU) also lists it under "Non-SI units and symbols whose continued use is deprecated".[6]

Units derived from the bar include the megabar (symbol: Mbar), kilobar (symbol: kbar), decibar (symbol: dbar), centibar (symbol: cbar), and millibar (symbol: mbar).

Definition and conversion

[edit]The bar is defined using the SI derived unit, pascal: 1 bar ≡ 100000 Pa ≡ 100000 N/m2.

Thus, 1 bar is equal to:

and 1 bar is approximately equal to:

- 0.98692327 atm

- 14.503774 psi

- 29.529983 inHg

- 750.06158 mmHg

- 750.06168 Torr

- 1019.716 centimetres of water (cmH2O) (1 bar approximately corresponds to the gauge pressure of water at a depth of 10 metres).

1 millibar (mbar) is equal to:

- 0.001 bar

- 100 Pa.

| Pascal | Bar | Technical atmosphere | Standard atmosphere | Torr | Pound per square inch | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Pa) | (bar) | (at) | (atm) | (Torr) | (psi) | |

| 1 Pa | — | 10−5 bar | 1.0197×10−5 at | 9.8692×10−6 atm | 7.5006×10−3 Torr | 0.000145037737730 lbf/in2 |

| 1 bar | 105 | — | = 1.0197 | = 0.98692 | = 750.06 | = 14.503773773022 |

| 1 at | 98066.5 | 0.980665 | — | 0.9678411053541 | 735.5592401 | 14.2233433071203 |

| 1 atm | ≡ 101325 | ≡ 1.01325 | 1.0332 | — | ≡ 760 | 14.6959487755142 |

| 1 Torr | 133.322368421 | 0.001333224 | 0.00135951 | 1/760 ≈ 0.001315789 | — | 0.019336775 |

| 1 psi | 6894.757293168 | 0.068947573 | 0.070306958 | 0.068045964 | 51.714932572 | — |

Origin

[edit]The word bar has its origin in the Ancient Greek word βάρος (baros), meaning weight. The unit's official symbol is bar;[citation needed] the earlier symbol b is now deprecated and conflicts with the uses of b denoting the unit barn or bit, but it is still encountered, especially as mb (rather than the proper mbar) to denote the millibar. Between 1793 and 1795, the word bar was used for a unit of mass (equal to the modern tonne) in an early version of the metric system.[9]

Usage

[edit]

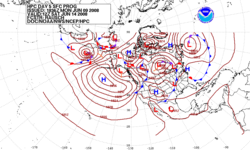

Atmospheric air pressure where standard atmospheric pressure is defined as 1013.25 mbar, 101.325 kPa, 1.01325 bar, which is about 14.7 pounds per square inch. Despite the millibar not being an SI unit, meteorologists and weather reporters worldwide have long measured air pressure in millibar as the values are convenient. After the advent of SI units, some meteorologists began using hectopascals (symbol hPa) which are numerically equivalent to millibar; for the same reason, the hectopascal is now the standard unit used to express barometric pressures in aviation in most countries. For example, the Meteorological Service of Canada uses kilopascals and hectopascals on their weather maps.[10][11] In contrast, Americans are familiar with the use of the millibar in US reports of hurricanes and other cyclonic storms.[12][13]

In fresh water, there is an approximate numerical equivalence between the change in pressure in decibar and the change in depth from the water surface in metres. Specifically, an increase of 1 decibar occurs for an increase in depth of 1.019716 m. In sea water with respect to the gravity variation, the latitude and the geopotential anomaly the pressure can be converted into metres' depth according to an empirical formula (UNESCO Tech. Paper 44, p. 25).[14] As a result, decibar is commonly used in oceanography.

In scuba diving, bar is also the most widely used unit to express pressure, e.g. 200 bar being a full standard scuba tank, and depth increments of 10 metre of seawater being equivalent to 1 bar of pressure.

Many engineers worldwide use the bar as a unit of pressure because, in much of their work, using pascals would involve using very large numbers. In measurement of vacuum and in vacuum engineering, residual pressures are typically given in millibar, although torr or millimetre of mercury (mmHg) were historically common.

Pressures resulting from deflagrations are often expressed in units of bar.[15]

In the automotive field, turbocharger boost is often described in bar outside the United States. Tire pressure is often specified in bar. In hydraulic machinery components are rated to the maximum system oil pressure, which is typically in hundreds of bar. For example, 300 bar is common for industrial fixed machinery.

In the maritime ship industries, pressures in piping systems, such as cooling water systems, is often measured in bar.

Unicode has characters for "mb" (U+33D4 ㏔ SQUARE MB SMALL), "bar" (U+3374 ㍴ SQUARE BAR) and ミリバール (U+334A ㍊ SQUARE MIRIBAARU; "millibar" spelt in katakana), but they exist only for compatibility with legacy Asian encodings and are not intended to be used in new documents.

The kilobar, equivalent to 100 MPa, is commonly used in geological systems, particularly in experimental petrology.

The abbreviations "bar(a)" and "bara" are sometimes used to indicate absolute pressures, and "bar(g)" and "barg" for gauge pressures. The usage is deprecated but still prevails in the oil industry (often by capitalized "BarG" and "BarA"). As gauge pressure is relative to the current ambient pressure, which may vary in absolute terms by about 50 mbar, "BarG" and "BarA" are not interconvertible. Fuller descriptions such as "gauge pressure of 2 bars" or "2-bar gauge" are recommended.[2][16]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- This article incorporates material from the Citizendium article "Bar (unit)", which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License but not under the GFDL.

- ^ a b The International System of Units (PDF), V3.01 (9th ed.), International Bureau of Weights and Measures, Aug 2024, ISBN 978-92-822-2272-0.

- ^ a b c British Standard BS 350:2004 Conversion Factors for Units.

- ^ "Nomenclature of the unit of absolute pressure, Charles F. Marvin, 1918" (PDF). noaa.gov. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 April 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Resolution 6 of the 9th CGPM, 1948, lists the bar (symbol bar) in a table illustrating rriting and printing of unit symbols

- ^ NIST Special Publication 1038 Archived 2016-03-19 at the Wayback Machine, Sec. 4.3.2; NIST Special Publication 811, 2008 edition Archived 2016-06-03 at the Wayback Machine, Sec. 5.2

- ^ International Astronomical Union Style Manual. Comm. 5 in IAU Transactions XXB, 1989, Table 6

- ^ Allen, William H. (1965-01-01). "Dictionary of Technical Terms for Aerospace Use". NASA Special Publication.

bar. … Some writers have used bar as equivalent to barye (1 dyne per square centimeter). … barye. … Sometimes called bar or microbar. … microbar (abbr μb). … In British literature the term barye has been used. … Unfortunately, the bar was once used in acoustics to mean 1 dyne per square centimeter, but this is no longer correct.

- ^ Marvin, Charles F. (1918-03-30). "Nomenclature of the Unit of Absolute Pressure" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. 46 (2). Washington: 73–75. Bibcode:1918MWRv...46...73M. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1918)46<73:NOTUOA>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-04-29.

T. W. Richards and A. E. Kennelly employed the term "bar" to signify a pressure of 1 dyne per square centimeter

- ^ "Instructions abrégée sur les mesures déduites de la grandeur de la terre et sur les calculs relatifs à leur division décimale, 1793: gravet, bar". 1793. Archived from the original on 2023-01-15. Retrieved 2016-05-06.

- ^ Canada, Environment (2013-04-16). "Canadian Weather at a Glance - Environment Canada". www.weatheroffice.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Canada, Environment (2013-04-16). "Canadian Weather - Environment Canada". www.weatheroffice.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ US government atmospheric pressure map

- ^ The Weather Channel

- ^ Scientific Committee on Oceanic Research (1983). "Algorithms for computation of fundamental properties of seawater" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-04-12. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

- ^ NFPA 68 Standard on Explosion Protection by Deflagration Venting (2023 ed.).

- ^ "What do the letters 'g' and 'a' denote after a pressure unit? (FAQ - Pressure) : FAQs : Reference : National Physical Laboratory". Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

External links

[edit]Bar (unit)

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Properties

Definition

The bar is a metric unit of pressure defined as exactly 100,000 pascals (Pa), or Pa.[1] Although not part of the International System of Units (SI), the bar is a non-SI unit accepted for use with the SI and is derived from the pascal, the SI unit of pressure.[1] Pressure itself is defined as force applied perpendicular to a surface, divided by the area of that surface, with the pascal representing one newton of force per square metre (N/m²).[1] The symbol for the bar is "bar", written in lowercase roman (upright) type and not italicized, consistent with SI style conventions for unit symbols.[1] This distinguishes it from related units such as the technical atmosphere (at), defined as exactly 98,066.5 Pa, and the standard atmosphere (atm), defined as exactly 101,325 Pa; unlike these, the bar provides an exact, round value of 100,000 Pa without approximation to natural atmospheric conditions.[4]Physical Significance

The bar unit derives its physical significance from its close approximation to the standard atmospheric pressure at Earth's sea level, making it a practical reference for environmental pressures. Precisely, 1 bar equals approximately 0.986923 atmospheres (atm), while the mean sea-level atmospheric pressure is about 1.01325 bar.[5][6] This near-equivalence positions the bar as an intuitive benchmark for typical ambient conditions, where exact adherence to SI units like the pascal is secondary to relatable scales in fields such as engineering and daily monitoring.[7] Submultiples of the bar extend its applicability to finer pressure measurements. The millibar (mbar), defined as 100 pascals, is widely used for quantifying smaller-scale pressures, including variations in atmospheric conditions.[8] Similarly, the microbar (μbar), or 0.1 pascals, serves in specialized domains like acoustics for sound pressure levels and seismology for detecting subtle ground vibrations.[9] In fluid dynamics, isobaric surfaces—regions where pressure remains constant—play a key role in modeling flows, with 1 bar levels often referenced as they align closely with near-surface atmospheric layers in both air and water systems.Conversions and Equivalents

Relation to SI Units

The bar is a metric unit of pressure defined exactly as 100 kilopascals (kPa), which corresponds to 100,000 pascals (Pa). Although the bar itself is not an SI unit, this exact equivalence facilitates its integration into SI-based calculations and measurements.[4] The pascal is the coherent derived SI unit for pressure, defined as the pressure resulting from a force of one newton acting uniformly over an area of one square metre, expressed as .[1] The inverse relationship follows directly from this definition, such that .[4] The bar also derives a practical connection to the hectopascal (hPa), an SI prefix multiple of the pascal widely used in atmospheric sciences, where and is exactly equivalent to one millibar (mbar).[2] Consequently, .[4] In SI contexts, pressure conversions between the bar and pascal are straightforward using the defining relationship: This equation ensures precise interoperability when expressing pressures in either unit.[4]Equivalents to Non-SI Units

The bar unit, defined as exactly 100,000 pascals, has several equivalents in traditional non-SI pressure units commonly used in engineering, meteorology, and industry. One bar is approximately equal to 14.5038 pounds per square inch (psi), a unit prevalent in the United States for measuring tire pressure, hydraulic systems, and mechanical specifications.[5] In vacuum technology and older scientific contexts, the bar relates to the millimeter of mercury (mmHg), also known as the torr, where 1 bar ≈ 750.06168 mmHg under standard conditions of 0°C and gravity of 9.80665 m/s².[10] This equivalence stems from the historical definition tying mmHg to atmospheric pressure fractions. The standard atmosphere (atm), defined exactly as 101,325 Pa, provides another key non-SI benchmark; thus, 1 bar ≈ 0.986923 atm, or conversely, 1 atm ≈ 1.01325 bar.[11] This slight difference highlights the bar's role as a rounded metric approximation to sea-level atmospheric pressure. For quick reference, the following table summarizes these conversions with approximate values rounded to six decimal places for common precision in applications; exact values derive from the bar's SI definition and require the intermediary pascal for computation.[12]| From Bar | To psi | To mmHg (torr) | To atm |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 14.503774 | 750.061683 | 0.986923 |