Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Keilah

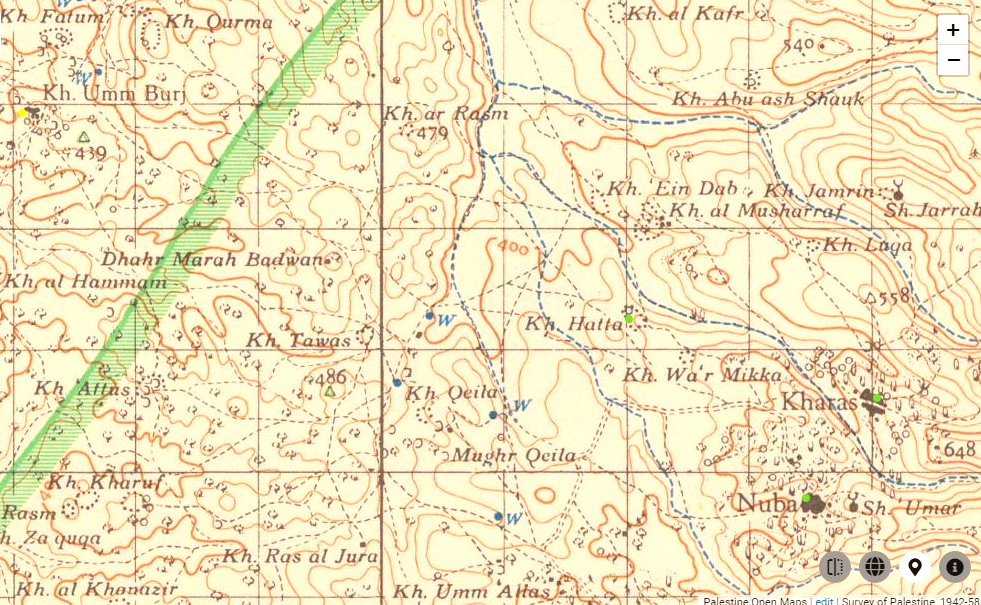

View on WikipediaKeilah (Hebrew: קְעִילָה, romanized: Qəʿilā, lit. 'Citadel') was a city in the lowlands of the Kingdom of Judah.[1] It is now a ruin known as Khirbet Qeyla near the modern village of Qila, Hebron, 7 miles (11 km) east of Bayt Jibrin and about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) west of Kharas.[2][3]

Key Information

History

[edit]Late Bronze

[edit]The earliest historical record of Keilah is found in the Amarna letters from the 14th century BCE.[2] In some of them, Qeilah and her king Shuwardatha are mentioned.[2] It is possible to infer from them the importance of this city among the cities of Canaan that bordered near Egypt before the conquest of Canaan by the Israelites.

Iron Age

[edit]According to the Hebrew Bible in the First Book of Samuel, the Philistines had made an inroad eastward as far as Keilah and had begun to appropriate the country for themselves by plundering its granaries until David prevented them.[4][5] Later, upon inquiry, he learnt that the inhabitants of the town, his native countrymen, would prove unfaithful to him, in that they would deliver him up to King Saul,[6] at which time he and his 600 men "departed from Keilah, and went whithersoever they could go”. They fled to the woods at Ziph. "And David was in the wilderness of Ziph, in a wood" (1 Samuel 23:15). Here his friend Jonathan sought him out "and strengthened his hand in God": this was the last meeting between David and Jonathan.[7]

Keilah is mentioned in the Book of Joshua (15:44) as one of the cities of the Shephelah "Lowland". Benjamin of Tudela identified Qaqun as ancient Keilah in 1160.[8] Conder and Kitchener, however, identified the biblical site with Khirbet Qeyla "seven English-miles from Bayt Jibrin"[9] and 11 km (7 mi) northwest of Hebron.[10] The site was earlier described by Eusebius in his Onomasticon as being "[nearly] eight milestones east of Eleutheropolis [now Bayt Jibrin], on the road to Hebron."[11] Victor Guérin, who visited Palestine between the years 1852–1888, also identified Keilah with the same ruin, Khirbet Kila (Arabic: خربة كيلا), near the modern village by that name,[12] a place situated a few kilometres south of Adullam (Khurbet esh Sheikh Madhkur) and west of Kharas. This view has been adopted by the Israel Antiquities Authority. Khirbet Qeyla, lies on the north side of the village of Qila. Guérin found here a subterranean and circular vault, apparently ancient; the vestiges of a wall surrounding the plateau, and on the side of a neighboring hill, tombs cut in the rock face.[13] The town is mentioned in the Amarna letters as Qilta.

Second Temple period

[edit]Keilah is mentioned in the Book of Nehemiah as one of the towns resettled by the Jewish exiles returning from the Babylonian captivity and who helped to construct the walls of Jerusalem during the reign of the Persian king Artaxerxes I.[2][14][15] Nehemiah further records that those returnees were the very descendants of the people who had formerly resided in the town before their banishment from the country, who had all returned to live in their former places of residence.[16]

During the Second Temple period, fig-cake shaped into round or square-shaped hard cakes (Hebrew: דְּבֵילָה, romanized: dəḇilā) were produced in Qeyla, and because of their outstanding and succulent quality and sweetness were permitted to be offered as such in the Temple in Jerusalem as first-fruits,[2] a thing customarily reserved only for fresh fruits (when brought from places near Jerusalem), and for raisins and dried figs when brought from distant places. This is mentioned in the Jerusalem Talmud in the tractate Bikkurim 3:3, and Solomon Sirilio's commentary there.[2]

The town's present residents are Bedouins expelled during 1948 Arab–Israeli War from areas around Beersheba.

Description of ruin

[edit]Khirbet Qeila (Ruin of Keilah) is situated on a terraced, dome-shaped hill at the end of a spur that descends to the east, adjacent to a small Arab village which bears the same name.[2] On the other side, it is surrounded by channels, which descend into the watercourse of Wadi es-Sur (an extension of the Elah Valley) and fortify it with a natural fortification.[2] Its area is about 50 dunams (12.3 acres).[2] Remains of walls can be seen on its slopes, and in the north is seen the ascent to the city gate, which is made like a ramp with a retaining wall.[2] At the foot of the tell, on the side of the road, burial caves were hewn.[2] The pottery finds at the tell indicate that it had an almost continuous settlement from the Bronze Age to the Crusader and Mamluk periods.[2]

The remnants of an old road leading from Keilah to the Elah Valley via Adullam can still be seen, and from Keilah to Tarqumiyah. Another ancient road breaks off from Keilah in the direction of Kefar Bish, now a ruin 4.5 kilometres (2.8 mi) to the west of Keilah, but once a Jewish village settled during the Roman occupation of Palestine.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ Joshua 15:44.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Amit n.d., p. 308 (s.v. קעילה).

- ^ Avi-Yonah 1976, p. 111.

- ^ Rainey 1983, p. 6.

- ^ 1 Samuel 23:1.

- ^ 1 Samuel 23:10–12.

- ^ 1 Samuel 23:16–18.

- ^ Conder 2002, p. p. 213.

- ^ Conder & Kitchener 1883, p. 314.

- ^ Tsumura 2007, p. 550.

- ^ Chapmann III & Taylor 2003, p. 65.

- ^ Guérin 1869, pp. 341–343; Guérin 1869, pp. 350-351.

- ^ Conder & Kitchener 1883, p. 118.

- ^ Nehemiah 3:17–18.

- ^ Josephus 1981, p. 236 (Antiquities 11.5.7.).

- ^ Nehemiah 7:6.

Bibliography

[edit]- Amit, David (n.d.). "Keilah (Qila)". In Ben-Yosef, Sefi (ed.). Israel Guide - Judaea (A useful encyclopedia for the knowledge of the country) (in Hebrew). Vol. 9. Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, in affiliation with the Israel Ministry of Defence. OCLC 745203905.

- Avi-Yonah, M. (1976). "Gazetteer of Roman Palestine". Qedem. 5. The Institute of Archaeology at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem; Carta: 3–112. JSTOR 43587090.

- Chapmann III, R.L.; Taylor, J.E., eds. (2003). Palestine in the Fourth Century A.D.: The Onomasticon by Eusebius of Caesarea. Translated by G.S.P. Freeman-Grenville. Jerusalem: Carta. ISBN 965-220-500-1. OCLC 937002750.

- Conder, C.R. (2002). Tent Work in Palestine: A Record of Discovery and Adventure. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4021-8987-6.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1883). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 3. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Guérin, V. (1869). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Judee, pt. 3. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Josephus (1981). Josephus Complete Works. Translated by William Whiston. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications. ISBN 0-8254-2951-X.

- Rainey, A.F. (1983). "The Biblical Shephelah of Judah". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. 251 (251). The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The American Schools of Oriental Research: 1–22. doi:10.2307/1356823. JSTOR 1356823.

- Tsumura, David Toshio (2007). The First Book of Samuel. Grand Rapids, Michigan: NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802823595. OCLC 918498742. (reprinted in 2009)

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Keilah". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Keilah". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

External links

[edit]- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 21: IAA, Wikimedia commons

Keilah

View on GrokipediaGeography and Identification

Location in the Shephelah

Keilah occupied a position in the Shephelah, the undulating lowland region of ancient Judah stretching between the coastal plain to the west and the Judean highlands to the east, spanning roughly 10 to 15 kilometers in width. This transitional zone of soft-sloping hills facilitated settlement at elevations conducive to fortified agriculture and defense, with Keilah situated approximately 11 kilometers (7 miles) east of Beit Guvrin (ancient Eleutheropolis) and about 8 miles from the route to Hebron.[3][4] Its placement southwest of Jerusalem underscored its role within Judah's southern frontier, approximately 30 kilometers from the capital as the crow flies.[3] The site's proximity to key valleys, including remnants of an ancient road connecting Keilah eastward to the Elah Valley via Adullam, positioned it to oversee lateral routes across the Shephelah's chalky terrain. These paths linked inland hill country with coastal access points, enabling oversight of caravan traffic and local exchange networks vital to Judah's economy.[1] The surrounding soils, enriched by seasonal wadis, supported intensive cultivation of grains and olives, hallmarks of Shephelah productivity that bolstered regional food security and surplus.[5] As a frontier settlement, Keilah's location rendered it a natural bulwark against westward threats from the Philistine pentapolis, controlling narrow passes prone to incursion while exposing it to raids across the undefended lowlands. This geopolitical vulnerability highlighted the Shephelah's dual function as both economic heartland and contested buffer, where dominance ensured agricultural yields and route security but invited conflict from maritime-oriented powers.[5][4]Consensus Identification with Khirbet Qeila

The predominant scholarly identification of biblical Keilah associates it with Khirbet Qeila, a ruin situated near the modern village of Qila in the Hebron district, approximately 13 kilometers northwest of Hebron and 11 kilometers east of Beit Guvrin (ancient Eleutheropolis). This location corresponds to the description in Joshua 15:44, which lists Keilah among the fortified cities of the Shephelah, the lowland foothills of Judah, positioned between sites such as Adullam to the north and Mareshah to the southwest.[6][1] The site's topographical fit is reinforced by its alignment with ancient travel routes and distances referenced in biblical itineraries, including the sequential placement in Joshua 15:42–44 alongside identifiable neighboring settlements. Eusebius, in his 4th-century CE Onomasticon, locates Keilah as a village eight Roman miles (approximately 12 kilometers) from Eleutheropolis on the road to Hebron, a measurement that precisely matches the distance from Khirbet Qeila to Beit Guvrin.[7][3] Archaeological surface surveys at Khirbet Qeila document occupational remains spanning from the Late Bronze Age through the Iron Age and into later periods, providing empirical support for settlement continuity that aligns with Keilah's recurring mentions in biblical narratives from the monarchy era onward.[8]Alternative Site Proposals and Debates

In the medieval period, Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela proposed identifying biblical Keilah with Qaqun, a site in northern Israel near the Jezreel Valley, during his journeys around 1160 CE; this view mismatched the biblical placement of Keilah in the Judean Shephelah amid cities like Adullam and Mareshah (Joshua 15:44).[1] Such early identifications relied on oral traditions and limited itineraries rather than systematic topography, leading to discrepancies with scriptural geography. Nineteenth-century surveys by explorers like those of the Palestine Exploration Fund initially debated several nearby ruins based on name resemblances and vague field observations, but by the 1880s, Claude Reignier Conder and Horatio Herbert Kitchener solidified Khirbet Qeila as the site through detailed mapping, noting its strategic hill position approximately 7 miles east of ancient Eleutheropolis (modern Beit Jibrin).[6] These debates stemmed from pre-GPS era imprecision, with alternatives like more distant or mismatched tells dismissed as modern geospatial data and remote sensing—employing satellite imagery and LiDAR since the 2000s—precisely correlate Qeila's coordinates (31°24′N 35°00′E) to biblical lists and narrative contexts, such as proximity to Philistine lowlands for David's defensive actions (1 Samuel 23).[7] Contemporary minority views occasionally link Keilah to sites like Khirbet Qeiyafa, citing shared Iron Age fortifications and Judahite pottery from the 10th century BCE, but these are refuted by Qeiyafa's Elah Valley overlook (distinct from Keilah's western exposure), separate biblical roles (e.g., Qeiyafa's potential tie to Shaaraim in 1 Samuel 17:52), and absence of matching destruction evidence or name traces.[9] Some minimalist scholars amplify identification uncertainties at under-excavated Qeila to question biblical historicity, emphasizing sparse stratigraphic data over convergent survey evidence of Iron Age remains; however, Qeila's pottery assemblages and fortification traces align empirically with 8th–6th century BCE Judahite activity, including layers indicative of Neo-Babylonian impacts around 586 BCE, absent in proposed alternatives.[10] This approach risks overstating evidential gaps influenced by ideological priors skeptical of monarchy-era narratives, as peer-reviewed surveys consistently favor Qeila's fit without requiring unsubstantiated relocations.Biblical Accounts

Allotment to the Tribe of Judah

Keilah appears in the biblical account of the Israelite conquest and division of Canaanite territory, listed in Joshua 15:44 as one of eleven cities in the Shephelah region allotted to the tribe of Judah following the initial conquest under Joshua.[11] This allotment included neighboring settlements such as Nezib, Achzib, and Mareshah, positioning Keilah within a cluster of fortified lowland sites that formed Judah's defensive frontier against Philistine incursions from the coastal plain.[12] The text describes these as pre-existing Canaanite urban centers captured and reassigned to Judahite clans, reflecting a transitional phase from Bronze Age Canaanite control to Iron Age Israelite settlement patterns.[13] The name Keilah, derived from the Hebrew root qʿl connoting a sling or protective enclosure, suggests an originally fortified Canaanite stronghold, consistent with its role in securing the western approaches to Judah's hill country.[14] Archaeological correlations with similar Shephelah sites indicate these allotments prioritized strategic elevations for surveillance and agriculture, enabling Judah to maintain territorial continuity amid ongoing threats from lowland powers.[13] This inheritance framework, detailed in the tribal lot-casting process, underscores Keilah's foundational status in Judah's territorial consolidation during the late 13th to early 12th centuries BCE, as cross-referenced with allotments like those of Libnah and Lachish in the same chapter.[15]David's Sojourn and Defense Against Philistines

According to 1 Samuel 23:1-5, David, then leading a band of approximately 400 men while fleeing King Saul, learned of Philistine raids on Keilah's threshing floors and inquired of God through the priest Abiathar's ephod for permission to intervene; assured of victory, he attacked the raiders, inflicted heavy losses, and seized their livestock, thereby rescuing the city.[16] In 1 Samuel 23:6-13, divine inquiry again warned David that Keilah's residents, despite his aid, would likely betray him to Saul out of fear, prompting his withdrawal with his followers—now numbering 600—to the wilderness of Ziph without incident.[16] This episode illustrates early Iron Age Judean border vulnerabilities, as Keilah's position in the Shephelah exposed it to incursions from Philistine centers like Gath, approximately 15 kilometers west, where raiders targeted harvest yields in unfortified or lightly defended rural areas.[13] David's success via a mobile force aligns with guerrilla tactics suited to outnumbered defenders exploiting terrain and surprise against plunder-focused detachments, rather than pitched battles; such dynamics reflect pragmatic military realism, where loyalty hinged on demonstrated protection amid Saul's internal threats.[17] The narrative's portrayal of David's band as opportunistic protectors demanding allegiance parallels 'Apiru groups in the 14th-century BCE Amarna Letters, documented as semi-nomadic outlaws or mercenaries who offered security to Canaanite towns in exchange for provisions, often shifting from banditry to localized leadership amid weak central authority.[18] Scholars such as Moshe Greenberg and George Mendenhall have drawn these analogies, noting empirical patterns of social fluidity where fugitive leaders like David consolidated followings from distressed debtors, refugees, and malcontents, testing communal fidelity before committing resources.[18] Archaeological remains at Khirbet Qeyla, the consensus site for biblical Keilah, include Iron Age I-II pottery and structural evidence consistent with a fortified settlement ca. 1000 BCE, supporting the plausibility of defensive actions against Philistine pressures during Judah's formative polity.[1] These findings counter revisionist assertions of a late invention for the United Monarchy, as Shephelah fortifications from this era—evidenced at nearby sites—indicate organized territorial control capable of repelling raids, rather than mere tribal anarchy.[19] The episode thus underscores causal factors in state emergence: reciprocal alliances forged through empirical aid, amid chronic external threats that incentivized unification under figures like David.[19]Post-Exilic References

In the Book of Nehemiah, composed circa 445 BCE during the Persian period following the Babylonian exile, Keilah is referenced in connection with the reconstruction of Jerusalem's walls. Hashabiah, identified as the ruler of half the district of Keilah, oversaw repairs for his portion alongside Levite workers, while Bavvai son of Henadad managed the other half-district.[20][21] This administrative role implies Keilah's resettlement by returning Judean exiles, as the district's leaders contributed labor and resources to the communal effort under Nehemiah's governance, reflecting organized local authority amid broader restoration initiatives.[22] The reference underscores partial repopulation in the Shephelah lowlands, where vulnerabilities to regional threats persisted despite Persian oversight, as evidenced by the divided district structure suggesting limited scale or defensive fragmentation rather than full pre-exilic prosperity.[1] No direct archaeological correlates confirm extensive rebuilding at Keilah itself during this era, but the textual notice aligns with sporadic Judean returnee settlements documented in Persian-era records, prioritizing fortified highland centers over exposed lowland sites like Keilah.[13] Additionally, 1 Chronicles 4:19, part of post-exilic genealogical compilations emphasizing Judahite lineage continuity, lists "the father of Keilah the Garmite" among descendants tied to the tribe of Judah, potentially denoting a patriarchal figure or eponymous founder associated with the locale.[23] This enumeration, while not detailing events, preserves Keilah's tribal affiliation in exilic-returnee records, indicating enduring cultural memory of its Judahite heritage amid demographic disruptions from conquest and deportation.[24] Such lists served to reaffirm land claims and identities for repatriated communities, though they reflect idealized rather than empirically verified post-exilic demographics.Historical Development

Late Bronze Age Settlement

The site of Khirbet Qeila, identified with biblical Keilah, exhibits evidence of Late Bronze Age (c. 1550–1200 BCE) occupation consistent with Canaanite village settlements in the Judean Shephelah, a region under Egyptian hegemony during this period. Surface surveys have recovered pottery sherds typifying local Canaanite production, including collared storage jars and cooking pots, indicative of agrarian communities focused on olive and grain cultivation amid the fertile lowlands.[25] These finds align with broader patterns in the Shephelah, where Egyptian administrative oversight is evidenced by imported scarabs and seals at nearby sites, suggesting Keilah functioned as a modest vassal outpost vulnerable to inter-city raids.[26] Textual corroboration comes from the Amarna letters (c. 1350 BCE), Egyptian diplomatic archives mentioning Keilah (as Qiltu) in accounts of conflicts involving local rulers and 'Apiru marauders, portraying it as an established town in the province of Canaan.[1] [27] This documentation underscores Keilah's role in the Late Bronze II political landscape, marked by Egyptian efforts to maintain control against decentralized threats, prior to the widespread disruptions of the Sea Peoples around 1200 BCE. Archaeological data remains limited due to the site's unexcavated status, but the continuity from Middle Bronze foundations implies persistent settlement without major fortification, transitioning toward Iron Age developments.[28]Iron Age Fortifications and Monarchy Period

Archaeological surveys and limited excavations at Khirbet Qeila reveal the emergence of fortifications during Iron Age I, circa 1000 BCE, characterized by substantial city walls and defensive towers that align with the strategic needs of early Judahite settlement in the Shephelah. These structures, including exposed wall segments and a gate ramp, suggest a response to threats from Philistine incursions, consistent with the biblical narrative of David's defense of the town against raiders targeting threshing floors. Pottery assemblages from the site include Iron IB-IIA forms dated 1050–930 BCE, indicating continuous occupation during the transition to state formation under the United Monarchy.[29][1] In Iron Age II (9th–7th centuries BCE), the site experienced prosperity reflective of Judahite royal administration, evidenced by the discovery of lmlk-stamped jar handles denoting centralized storage and distribution systems integrated into the kingdom's economy. Ashlar masonry elements and grain silos point to enhanced agricultural processing and defensive capabilities, paralleling developments at peer sites like Lachish, where comparable gate complexes and casemate walls facilitated control over lowland routes. These features underscore Keilah's role as a fortified outpost in the Kingdom of Judah, supporting empirical indications of a structured monarchy rather than nomadic or minimal polities.[30][31][1]Divided Kingdom and Assyrian Threats

Following the schism of the united monarchy circa 930 BCE, Keilah functioned as a Judean frontier settlement in the Shephelah, bolstered by Rehoboam's fortification program to defend against incursions from the Kingdom of Israel and Philistine territories.[32] This early Divided Kingdom era enhancement aligned with Judah's strategy to consolidate control over lowland routes, as evidenced by the site's Iron Age II architectural remains consistent with regional defensive expansions.[33] By the mid-8th century BCE, Neo-Assyrian expansion under Tiglath-Pileser III and Sargon II exerted mounting pressure on Judah's periphery, though direct assaults on interior Shephelah sites like Keilah were averted through tribute payments. Sargon's 712 BCE campaign against Ashdod, a Philistine stronghold proximate to Judah, prompted Hezekiah's predecessor to submit vassalage, per Assyrian display inscriptions, thereby sparing immediate devastation but imposing economic strains via heavy indemnities that curtailed trade and ceramic imports across Judahite lowlands.[34] Archaeological surveys indicate a qualitative shift in Shephelah pottery assemblages during this phase, reflecting reduced coastal exchanges amid Assyrian dominance rather than wholesale depopulation.[35] Hezekiah's reign (circa 715–686 BCE) saw Keilah integrated into Judah's anti-Assyrian preparations, as suggested by an lmlk-stamped jar handle unearthed at Khirbet Qila, linking the site to royal storage networks for provisioning fortifications ahead of Sennacherib's 701 BCE offensive.[36] While Sennacherib's annals enumerate 46 captured Judean strongholds—primarily coastal and western Shephelah centers like Lachish—Keilah evaded explicit mention of siege or razing, implying it withstood or bypassed the brunt through Hezekiah's tactical rebellions and alliances.[37] These records corroborate biblical depictions of Judahite fortitude and tribute extraction (2 Kings 18:13–16), substantiating resistance over narratives minimizing Judah's military capacity, as Assyrian boasts acknowledge Hezekiah's confinement yet failure to subdue Jerusalem outright.[38] The resultant tribute burdens, however, fostered long-term fiscal erosion in outposts like Keilah, evident in sustained but diminished settlement continuity into the late Iron Age II.Babylonian Conquest and Destruction

The Babylonian campaign led by King Nebuchadnezzar II against the Kingdom of Judah in 587/586 BCE represented the final subjugation of the region following Zedekiah's rebellion against Babylonian overlordship, which violated terms established after the 597 BCE deportation of elites from Jerusalem. This military operation systematically targeted fortified towns across Judah, including lowland sites like Keilah in the Shephelah, resulting in widespread destruction that ended Judahite political independence. Historical records, corroborated by Babylonian chronicles, indicate the campaign involved sieges, deportations, and razing of structures, with Jerusalem falling on July 18, 586 BCE after an 18-month blockade.[39] Archaeological strata from late Iron Age II contexts in the Shephelah reveal consistent markers of violent conquest around this period, including ash-filled destruction layers, collapsed buildings, and iron arrowheads of Babylonian typology at nearby sites such as Lachish and Azekah, where siege ramps and administrative letters detail the assaults. At Khirbet Qila, identified as Keilah, limited excavations have uncovered Iron Age II fortifications and storage jar handles bearing royal Judahite stamps, but no subsequent occupation until the Persian era, aligning with regional patterns of depopulation and abandonment post-586 BCE. This endpoint of activity implies the site's incorporation into the broader devastation, with deportations reducing the population and halting settlement in exposed lowland areas.[40][1] Contributing causes included Judah's strategic overextension through repeated revolts, exacerbated by unreliable alliances with Egypt and chronic resource strain from tribute payments and defensive mobilizations, which left peripheral towns like Keilah vulnerable to Babylonian forces advancing through Philistia-controlled lowlands. In contrast to more defensible highland enclaves that exhibited partial continuity under Babylonian administration, Shephelah settlements faced heightened exposure due to their proximity to invasion routes and agricultural value, prompting thorough dismantling to prevent future resistance. The resultant socioeconomic collapse, evidenced by a 70-80% drop in regional pottery production and settlement density, underscored the causal efficacy of imperial enforcement in curtailing local autonomy.[41]Archaeological Evidence

Major Excavation Efforts

Archaeological investigations at Khirbet Qeila, identified as biblical Keilah, have primarily consisted of surveys and limited soundings rather than large-scale excavations. Early 20th-century probes by William F. Albright revealed Iron Age strata, supporting evidence of occupation during the monarchy period. Yohanan Aharoni also conducted excavations at the site, uncovering remains consistent with fortified settlements from the Iron Age. No extensive digs have occurred since the mid-20th century, with efforts shifting to surveys and monitoring due to the site's location in a contested area. The Israel Antiquities Authority oversees ongoing preservation and periodic assessments, focusing on threats like looting amid regional conflicts.[42] In October 2020, a trial excavation southeast of Khirbat Keila documented additional features, but full-scale work remains limited.[43] These non-invasive methods, including surface collections, have mapped unexcavated portions without disturbing strata, prioritizing data preservation over interpretive expansion.[42]Key Artifacts and Structures

Excavations at Khirbet Qila have uncovered sections of Iron Age fortifications, including a 20-meter segment of city wall and a rectangular tower measuring 5 by 4 meters. These structures, associated with the Iron Age II period (ca. 1000–586 BCE), reflect defensive architecture typical of Judahite settlements in the Shephelah region. A notable artifact is a storage jar handle stamped with an lmlk ("belonging to the king") impression, featuring a two-winged symbol flanked by Paleo-Hebrew inscriptions reading lmlk above and a place name (possibly ḥbrn or similar) below. Dated to the late 8th–early 7th century BCE during the reigns of Hezekiah or Manasseh, this seal evidences Keilah's role in the Kingdom of Judah's royal provisioning system, involving large-scale olive oil and wine storage for military and administrative purposes. Such impressions, found across Judahite sites, indicate centralized control and economic integration.[36] Pottery assemblages from the site include Iron Age II Judahite forms such as cooking pots, storage jars, and bowls, consistent with regional ceramic traditions and pointing to sustained settlement activity. Surveys and limited digs have also yielded rock-cut tombs and remnants of an aqueduct, likely supporting water management in this agriculturally vital area. Evidence of destruction layers from the 6th century BCE Babylonian campaign aligns with broader Judahite site patterns, including ash and collapsed structures, though specific debris like charred beams at Keilah awaits fuller publication.Correlation with Biblical Narratives

Archaeological evidence from Khirbet Qila supports the biblical depiction of Keilah as a fortified settlement in the Iron Age IIB period, consistent with its role in 1 Samuel 23 as a defensible city with gates and bars that David reinforced against Philistine incursions. Surface surveys and limited excavations have revealed structural remains indicative of defensive architecture, including wall segments and strategic positioning on a terraced hill overlooking the Shephelah lowlands, aligning with the narrative of a town capable of withstanding raids from Philistine territory.[2][44] The absence of pig bones in faunal assemblages from Judean Shephelah sites, including patterns observed in comparable excavations, correlates with biblical descriptions of Israelite dietary practices prohibiting pork, distinguishing Keilah's material culture from contemporaneous Philistine settlements where pig consumption exceeds 10-20% of remains. This ethnic marker reinforces the historicity of Keilah as a Judahite outpost rather than a Philistine enclave, as the site's Iron Age pottery and storage jars lack Philistine bichrome styles.[45][46] Lmlk-stamped jar handles recovered at Khirbet Qila, dated to the late 8th century BCE under Hezekiah, attest to centralized Judahite administrative control, echoing Keilah's listing among royal cities in Joshua 15:44 and its strategic vulnerability during Assyrian campaigns prophesied in Micah 1:13-15. While no direct destruction layer has been definitively linked to the 586 BCE Babylonian conquest at the site, the regional pattern of fiery terminations across Judahite fortresses—evidenced by ash layers, collapsed walls, and abrupt ceramic horizons—validates Jeremiah's warnings of divine judgment via Nebuchadnezzar, providing causal continuity absent in minimalist interpretations that posit legendary embellishment without explanatory alternatives for the empirical data.[30][47] Critics noting the lack of inscriptions naming David or specific events at Keilah highlight valid evidential gaps, as epigraphic records from 10th-century BCE Judah remain sparse; however, the cumulative positive indicators—fortified layout, Judahite ceramics, and administrative stamps—prioritize archaeological congruence over arguments from silence, which fail to account for the site's occupation continuity into the monarchy era.[48]Site Description and Preservation

Physical Layout of the Ruins

The ruins at Khirbet Qeila occupy a terraced tell located at 31°40′N 34°59′E, consisting of a central mound with surrounding lower slopes.[49] The core mound maintains contours attributable to Iron Age settlement, while erosion and ongoing plowing activities have diminished surface visibility of structural details. Excavations in Area B exposed a 20-meter segment of the ancient city wall alongside a rectangular tower measuring 5 by 4 meters, indicating fortified elements on the lower city perimeter. Rock-cut tombs and wine presses are present in the vicinity, evidencing Hellenistic-period agricultural and burial reuse of the site.[51] No significant tourism has impacted preservation, allowing the visible remains—primarily wall segments on slopes and access paths—to convey the original fortified layout without modern alterations.[52]Environmental and Strategic Features

Keilah occupies a terraced, dome-shaped hill at the eastern end of a spur descending from the Judean highlands, bordered by deep wadis on three sides that enhanced natural defensibility and afforded elevated views for monitoring approaches from the valleys below.[1] The site's hilly terrain in the Shephelah region, characterized by rolling foothills with fertile rendzina and terra rossa soils derived from loess deposits, supported rainfed agriculture focused on grains, figs, and olives, though limited precipitation—averaging under 500 mm annually—necessitated cisterns for water storage.[53][35] Positioned approximately 15 km northwest of Hebron at around 430 meters elevation, Keilah overlooked key routes connecting the Philistine coastal plain to the interior highlands via passes like that near Beit Jibrin, establishing it as a chokepoint for north-south trade and military movements that invited recurrent contestation.[1][22] The open, undulating landscape favored ranged weaponry such as slings over close-quarters or chariot tactics, aligning with the site's etymological roots potentially linked to terms for slinging or fortification.[54] Contemporary olive cultivation on ancient-style terraces perpetuates adaptations to the slope-prone soils, underscoring enduring agricultural viability despite erosion risks.[53]

References

- https://www.[researchgate](/page/ResearchGate).net/publication/388498111_The_Battle_to_Protect_Archaeological_Sites_in_the_West_Bank_Archaeological_sites_throughout_the_occupied_West_Bank_have_suffered_from_Israeli_appropriation_and_annexation_amid_the_escalation_of_violen