Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

OpenGL

View on Wikipedia

| OpenGL | |

|---|---|

| |

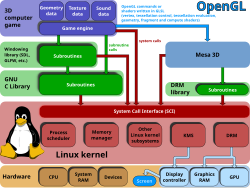

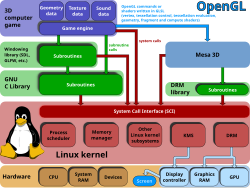

A diagram of how video games on Linux outsource real-time rendering calculations to a GPU using OpenGL. | |

| Original author | Silicon Graphics |

| Developers | Khronos Group (formerly ARB) |

| Initial release | June 30, 1992 |

| Stable release | 4.6[1] |

| Written in | C[2] |

| Successor | Vulkan |

| Type | 3D graphics API |

| License |

|

| Website | opengl.org |

OpenGL (Open Graphics Library[4]) is a cross-language, cross-platform application programming interface (API) for rendering 2D and 3D vector graphics. The API is typically used to interact with a graphics processing unit (GPU), to achieve hardware-accelerated rendering.

Silicon Graphics, Inc. (SGI) began developing OpenGL in 1991 and released it on June 30, 1992.[5][6] It is used for a variety of applications, including computer-aided design (CAD), video games, scientific visualization, virtual reality, and flight simulation. Since 2006, OpenGL has been managed by the non-profit technology consortium Khronos Group.[7]

Design

[edit]

The OpenGL specification describes an abstract application programming interface (API) for drawing 2D and 3D graphics. It is designed to be implemented mostly or entirely using hardware acceleration such as a GPU, although it is possible for the API to be implemented entirely in software running on a CPU.

The API is defined as a set of functions which may be called by the client program, alongside a set of named integer constants (for example, the constant GL_TEXTURE_2D, which corresponds to the decimal number 3553). Although the function definitions are superficially similar to those of the programming language C, they are language-independent. As such, OpenGL has many language bindings, some of the most noteworthy being the JavaScript binding WebGL (API, based on OpenGL ES 2.0, for 3D rendering from within a web browser); the C bindings WGL, GLX and CGL; the C binding provided by iOS; and the Java and C bindings provided by Android.

In addition to being language-independent, OpenGL is also cross-platform. The specification says nothing on the subject of obtaining and managing an OpenGL context, leaving this as a detail of the underlying windowing system. For the same reason, OpenGL is purely concerned with rendering, providing no APIs related to input, audio, or windowing.

Development

[edit]OpenGL is no longer in active development; whereas between 2001 and 2014, OpenGL specification was updated mostly on a yearly basis, with two releases (3.1 and 3.2) taking place in 2009 and three (3.3, 4.0 and 4.1) in 2010. The latest OpenGL specification 4.6 was released in 2017 after a three-year break, and was limited to inclusion of eleven existing ARB and EXT[a] extensions into the core profile.[9]

Active development of OpenGL was dropped in favor of the Vulkan API, released in 2016, and codenamed glNext during initial development. In 2017, Khronos Group announced that OpenGL ES would not have new versions[10] [11] and has since concentrated on development of Vulkan and other technologies.[12][13] As a result, certain capabilities offered by modern GPUs, e.g. ray tracing, are not supported by the OpenGL standard. However, support for newer features might be provided through the vendor-specific OpenGL extensions.[14][15]

New versions of the OpenGL specifications are released by the Khronos Group, each of which extends the API to support various new features. The details of each version are decided by consensus between the Group's members, including graphics card manufacturers, operating system designers, and general technology companies such as Mozilla and Google.[16]

In addition to the features required by the core API, graphics processing unit (GPU) vendors may provide additional functionality in the form of extensions. Extensions may introduce new functions and new constants, and may relax or remove restrictions on existing OpenGL functions. Vendors can use extensions to expose custom APIs without needing support from other vendors or the Khronos Group as a whole, which greatly increases the flexibility of OpenGL. All extensions are collected in, and defined by, the OpenGL Registry.[17]

The features introduced by each new version of OpenGL are typically formed from the combined features of several widely implemented extensions, especially extensions of type ARB or EXT.

Documentation

[edit]The OpenGL Architecture Review Board released a series of manuals along with the specification which have been updated to track changes in the API. These are commonly referred to by the colors of their covers:

- The Red Book

- OpenGL Programming Guide, 9th Edition. ISBN 978-0-134-49549-1

- The Official Guide to Learning OpenGL, Version 4.5 with SPIR-V

- The Orange Book

- OpenGL Shading Language, 3rd edition. ISBN 0-321-63763-1

- A tutorial and reference book for GLSL.

Historic books (pre-OpenGL 2.0):

- The Green Book

- OpenGL Programming for the X Window System. ISBN 978-0-201-48359-8

- A book about X11 interfacing and OpenGL Utility Toolkit (GLUT).

- The Blue Book

- OpenGL Reference manual, 4th edition. ISBN 0-321-17383-X

- Essentially a hard-copy printout of the Unix manual (man) pages for OpenGL.

- Includes a poster-sized fold-out diagram showing the structure of an idealised OpenGL implementation.

- The Alpha Book (white cover)

- OpenGL Programming for Windows 95 and Windows NT. ISBN 0-201-40709-4

- A book about interfacing OpenGL with Microsoft Windows.

OpenGL's documentation is also accessible via its official webpage.[18]

Associated libraries

[edit]The earliest versions of OpenGL were released with a companion library called the OpenGL Utility Library (GLU). It provided simple, useful features which were unlikely to be supported in contemporary hardware, such as tessellating, and generating mipmaps and primitive shapes. The GLU specification was last updated in 1998 and depends on OpenGL features which are now deprecated.

Context and window toolkits

[edit]Given that creating an OpenGL context is quite a complex process, and given that it varies between operating systems, automatic OpenGL context creation has become a common feature of several game-development and user-interface libraries, including SDL, Allegro, SFML, FLTK, and Qt. A few libraries have been designed solely to produce an OpenGL-capable window. The first such library was OpenGL Utility Toolkit (GLUT), later superseded by freeglut. GLFW is a newer alternative.[19]

- These toolkits are designed to create and manage OpenGL windows, and manage input, but little beyond that.[20]

- GLFW – A cross-platform windowing and keyboard-mouse-joystick handler; is more game-oriented

- freeglut – A cross-platform windowing and keyboard-mouse handler; its API is a superset of the GLUT API, and it is more stable and up to date than GLUT

- OpenGL Utility Toolkit (GLUT) – An old windowing handler, no longer maintained.

- Several "multimedia libraries" can create OpenGL windows, in addition to input, sound and other tasks useful for game-like applications

- Allegro 5 – A cross-platform multimedia library with a C API focused on game development

- Simple DirectMedia Layer (SDL) – A cross-platform multimedia library with a C API

- SFML – A cross-platform multimedia library with a C++ API and multiple other bindings to languages such as C#, Java, Haskell, and Go

- Widget toolkits

Extension loading libraries

[edit]Given the high workload involved in identifying and loading OpenGL extensions, a few libraries have been designed which load all available extensions and functions automatically. Examples include OpenGL Easy Extension library (GLEE), OpenGL Extension Wrangler Library (GLEW) and glbinding. Extensions are also loaded automatically by most language bindings, such as Java OpenGL, PyOpenGL and WebGL.

Implementations

[edit]

glxinfo, showing information of Mesa implementation of OpenGL on a system and glxgears, a program to test OpenGL implementation on a systemMesa 3D is an open-source implementation of OpenGL. It can do pure software rendering, and it may also use hardware acceleration on BSD, Linux, and other platforms by taking advantage of the Direct Rendering Infrastructure. As of version 20.0, it implements version 4.6 of the OpenGL standard.

History

[edit]In the 1980s, developing software that could function with a wide range of graphics hardware was a challenge without a cross-platform library. Software developers wrote custom interfaces and drivers for each piece of hardware. This was expensive and resulted in multiplication of effort.

By the early 1990s, Silicon Graphics (SGI) was a leader in 3D graphics for workstations. Their IRIS GL API[21][22] became the industry standard, as IRIS GL was considered easier to use,[by whom?] and it supported immediate mode rendering, therefore being faster[23] than competitors like PHIGS.

SGI's competitors (including Sun Microsystems, Hewlett-Packard and IBM) were also able to bring to market 3D hardware supported by extensions made to the PHIGS standard, which pressured SGI to open source a version of IRIS GL as a public standard called OpenGL.

However, SGI had many customers for whom the change from IRIS GL to OpenGL would demand significant investment. Moreover, IRIS GL had API functions that were irrelevant to 3D graphics. For example, it included a windowing, keyboard and mouse API, in part because it was developed before the X Window System and Sun's NeWS.[24] IRIS GL libraries were heavily tied into SGI's proprietary graphics hardware and could not be open sourced as-is due to hardware patents and trade secrets These factors required SGI to continue to support the advanced and proprietary Iris Inventor and Iris Performer programming APIs while market support for OpenGL matured.

One of the restrictions of IRIS GL was that it only provided access to features supported by the underlying hardware. If the graphics hardware did not support a feature natively, then the application could not use it. OpenGL overcame this problem by providing software implementations of features unsupported by hardware, allowing applications to use advanced graphics on relatively low-powered systems. OpenGL standardized access to hardware, pushed the development responsibility of hardware interface programs (device drivers) to hardware manufacturers, and delegated windowing functions to the underlying operating system. With so many different kinds of graphics hardware, getting them all to speak the same language in this way had a remarkable impact by giving software developers a higher-level platform for 3D-software development.

In 1992,[25] SGI led the creation of the OpenGL Architecture Review Board (OpenGL ARB), the group of companies that would maintain and expand the OpenGL specification in the future. Two years later, they also played with the idea of releasing something called "OpenGL++" which included elements such as a scene-graph API (presumably based on their Performer technology). The specification was circulated among a few interested parties – but never turned into a product.[26]

Released in 1996, Microsoft's Direct3D eventually became the main competitor of OpenGL. Over 50 game developers signed an open letter to Microsoft, released on June 12, 1997, calling on the company to actively support OpenGL.[27] On December 17, 1997,[28] Microsoft and SGI initiated the Fahrenheit project, which was a joint effort with the goal of unifying the OpenGL and Direct3D interfaces (and adding a scene-graph API too). In 1998, Hewlett-Packard joined the project.[29] It initially showed some promise of bringing order to the world of interactive 3D computer graphics APIs, but on account of financial constraints at SGI, strategic reasons at Microsoft, and a general lack of industry support, it was abandoned in 1999.[30]

In July 2006, the OpenGL Architecture Review Board voted to transfer control of the OpenGL API standard to the Khronos Group.[31][32]

Industry support

[edit]This section needs expansion with: more historical background when support was being added. You can help by adding to it. (January 2023) |

Despite the emergence of newer graphics APIs like its successor Vulkan or Metal, OpenGL continues to be a widely used standard. This continued relevance is supported by several factors: ongoing development with new extensions and driver optimizations, its cross-platform compatibility, and the availability of compatibility layers like ANGLE and Zink. These layers allow OpenGL to run efficiently on top of Vulkan and Metal, offering a pathway for continued use or gradual transitions for developers.[33][34][better source needed]

However, the graphics API landscape has been shifting, where some companies are moving away from OpenGL. Back in June 2018, Apple has deprecated OpenGL APIs on all of their platforms (iOS, macOS and tvOS), strongly encouraging developers to use their proprietary Metal API, which was introduced in 2014.[35]

Game developers have also begun to adopt newer APIs. id Software, who has been using OpenGL in their games since the late 1990s in games such as GLQuake[36] or some games of the Doom franchise,[37] transitioned away to its successor Vulkan in its id Tech 7 engine in 2016.[38] They first supported Vulkan in an update for their id Tech 6 engine. The company's first licensed use of OpenGL was in its Quake II engine, also known as id Tech 2.[39] In March 2023, Valve removed OpenGL support from Dota 2 in favor of Vulkan.[40] Atypical Games, with support from Samsung, updated their game engine to use Vulkan, rather than OpenGL, across all non-Apple platforms.[41]

The Khronos Group, the consortium responsible for OpenGL's development, has stopped providing support for OpenGL.[citation needed] It has not received a number of modern graphics technologies, such as hardware accelerated Ray Tracing, on-GPU video decoding, and advanced anti-aliasing algorithms like Nvidia DLSS[42] and AMD FSR[43]

Google's Fuchsia OS, while using Vulkan natively and requiring a Vulkan-conformant GPU, still intends to support OpenGL on top of Vulkan via the ANGLE translation layer.[44]

Version history

[edit]The first version of OpenGL, version 1.0, was released on June 30, 1992, by Mark Segal and Kurt Akeley. Since then, OpenGL has occasionally been extended by releasing a new version of the specification. Such releases define a baseline set of features which all conforming graphics cards must support, and against which new extensions can more easily be written. Each new version of OpenGL tends to incorporate several extensions which have widespread support among graphics-card vendors, although the details of those extensions may be changed.

| Version | Release Date | Features |

|---|---|---|

| 1.1 | March 4, 1997[45][46] | Texture objects, Vertex Arrays |

| 1.2 | March 16, 1998 | 3D textures, BGRA and packed pixel formats,[47] introduction of the imaging subset useful to image-processing applications |

| 1.2.1 | October 14, 1998 | A concept of ARB extensions |

| 1.3 | August 14, 2001 | Multitexturing, multisampling, texture compression |

| 1.4 | July 24, 2002 | Depth textures, GLSlang[48] |

| 1.5 | July 29, 2003 | Vertex Buffer Object (VBO), Occlusion Queries[49] |

| 2.0 | September 7, 2004 | GLSL 1.1, MRT, Non Power of Two textures, Point Sprites,[50] Two-sided stencil[49] |

| 2.1 | July 2, 2006 | GLSL 1.2, Pixel Buffer Object (PBO), sRGB Textures[49] |

| 3.0 | August 11, 2008 | GLSL 1.3, Texture Arrays, Conditional rendering, Frame Buffer Object (FBO)[51] |

| 3.1 | March 24, 2009 | GLSL 1.4, Instancing, Texture Buffer Object, Uniform Buffer Object, Primitive restart[52] |

| 3.2 | August 3, 2009 | GLSL 1.5, Geometry Shader, Multi-sampled textures[53] |

| 3.3 | March 11, 2010 | GLSL 3.30, Backports as much function as possible from the OpenGL 4.0 specification |

| 4.0 | March 11, 2010 | GLSL 4.00, Tessellation on GPU, shaders with 64-bit precision[54] |

| 4.1 | July 26, 2010 | GLSL 4.10, Developer-friendly debug outputs,[b] compatibility with OpenGL ES 2.0[55] |

| 4.2 | August 8, 2011[56] | GLSL 4.20, Shaders with atomic counters, draw transform feedback instanced, shader packing, performance improvements |

| 4.3 | August 6, 2012[57] | GLSL 4.30, Compute shaders leveraging GPU parallelism, shader storage buffer objects, high-quality ETC2/EAC texture compression, increased memory security, a multi-application robustness extension, compatibility with OpenGL ES 3.0[58] |

| 4.4 | July 22, 2013[59] | GLSL 4.40, Buffer Placement Control, Efficient Asynchronous Queries, Shader Variable Layout, Efficient Multiple Object Binding, Streamlined Porting of Direct3D applications, Bindless Texture Extension, Sparse Texture Extension[59] |

| 4.5 | August 11, 2014[17][60] | GLSL 4.50, Direct State Access (DSA), Flush Control, Robustness, OpenGL ES 3.1 API and shader compatibility, DX11 emulation features |

| 4.6 | July 31, 2017[9][61] | GLSL 4.60, More efficient geometry processing and shader execution, more information, no error context, polygon offset clamp, SPIR-V, anisotropic filtering |

OpenGL 2.0

[edit]Release date: September 7, 2004

OpenGL 2.0 was originally conceived by 3Dlabs to address concerns that OpenGL was stagnating and lacked a strong direction.[62] 3Dlabs proposed a number of major additions to the standard. Most of these were, at the time, rejected by the ARB or otherwise never came to fruition in the form that 3Dlabs proposed. However, their proposal for a C-style shading language was eventually completed, resulting in the current formulation of the OpenGL Shading Language (GLSL or GLslang). Like the assembly-like shading languages it was replacing, it allowed replacing the fixed-function vertex and fragment pipe with shaders, though this time written in a C-like high-level language.

The design of GLSL was notable for making relatively few concessions to the limits of the hardware then available. This harked back to the earlier tradition of OpenGL setting an ambitious, forward-looking target for 3D accelerators rather than merely tracking the state of currently available hardware. The final OpenGL 2.0 specification[63] includes support for GLSL.

Longs Peak and OpenGL 3.0

[edit]Before the release of OpenGL 3.0, the new revision had the codename Longs Peak. At the time of its original announcement, Longs Peak was presented as the first major API revision in OpenGL's lifetime. It consisted of an overhaul to the way that OpenGL works, calling for fundamental changes to the API.

The draft introduced a change to object management. The GL 2.1 object model was built upon the state-based design of OpenGL. That is, to modify an object or to use it, one needs to bind the object to the state system, then make modifications to the state or perform function calls that use the bound object.

Because of OpenGL's use of a state system, objects must be mutable. That is, the basic structure of an object can change at any time, even if the rendering pipeline is asynchronously using that object. A texture object can be redefined from 2D to 3D. This requires any OpenGL implementations to add a degree of complexity to internal object management.

Under the Longs Peak API, object creation would become atomic, using templates to define the properties of an object which would be created with one function call. The object could then be used immediately across multiple threads. Objects would also be immutable; however, they could have their contents changed and updated. For example, a texture could change its image, but its size and format could not be changed.

To support backwards compatibility, the old state based API would still be available, but no new functionality would be exposed via the old API in later versions of OpenGL. This would have allowed legacy code bases, such as the majority of CAD products, to continue to run while other software could be written against or ported to the new API.

Longs Peak was initially due to be finalized in September 2007 under the name OpenGL 3.0, but the Khronos Group announced on October 30 that it had run into several issues that it wished to address before releasing the specification.[64] As a result, the spec was delayed, and the Khronos Group went into a media blackout until the release of the final OpenGL 3.0 spec.

The final specification proved far less revolutionary than the Longs Peak proposal. Instead of removing all immediate mode and fixed functionality (non-shader mode), the spec included them as deprecated features. The proposed object model was not included, and no plans have been announced to include it in any future revisions. As a result, the API remained largely the same with a few existing extensions being promoted to core functionality. Among some developer groups this decision caused something of an uproar,[65] with many developers professing that they would switch to DirectX in protest. Most complaints revolved around the lack of communication by Khronos to the development community and multiple features being discarded that were viewed favorably by many. Other frustrations included the requirement of DirectX 10 level hardware to use OpenGL 3.0 and the absence of geometry shaders and instanced rendering as core features.

Other sources reported that the community reaction was not quite as severe as originally presented,[66] with many vendors showing support for the update.[67][68]

OpenGL 3.0

[edit]Release date: August 11, 2008

OpenGL 3.0 introduced a deprecation mechanism to simplify future revisions of the API. Certain features, marked as deprecated, could be completely disabled by requesting a forward-compatible context from the windowing system. OpenGL 3.0 features could still be accessed alongside these deprecated features, however, by requesting a full context.

Deprecated features include:

- All fixed-function vertex and fragment processing

- Direct-mode rendering, using glBegin and glEnd

- Display lists

- Indexed-color rendering targets

- OpenGL Shading Language versions 1.10 and 1.20

Hardware support: Nvidia GeForce 8 Series and newer, ATI Radeon HD 2000 series and newer.

OpenGL 3.1

[edit]Release date: March 24, 2009

OpenGL 3.1 fully removed all of the features which were deprecated in version 3.0, with the exception of wide lines. From this version onwards, it's not possible to access new features using a full context, or to access deprecated features using a forward-compatible context. An exception to the former rule is made if the implementation supports the ARB_compatibility extension, but this is not guaranteed.

Hardware support: Mesa supports ARM Panfrost with Version 21.0.

OpenGL 3.2

[edit]Release date: August 3, 2009

OpenGL 3.2 further built on the deprecation mechanisms introduced by OpenGL 3.0, by dividing the specification into a core profile and compatibility profile. Compatibility contexts include the previously removed fixed-function APIs, equivalent to the ARB_compatibility extension released alongside OpenGL 3.1, while core contexts do not. OpenGL 3.2 also included an upgrade to GLSL version 1.50.

OpenGL 3.3

[edit]Release date: March 11, 2010

Mesa supports software Driver SWR, softpipe and for older Nvidia cards with NV50. Several minor additions were made, with the goal of retaining as much functionality as possible from OpenGL 4.0, while keeping support for older hardware. Support is also added for GLSL version 3.30, major and minor versions now match with OpenGL.

OpenGL 4.0

[edit]Release date: March 11, 2010

OpenGL 4.0 was released alongside version 3.3. It was designed for hardware able to support Direct3D 11.

As in OpenGL 3.0, this version of OpenGL contains a high number of fairly inconsequential extensions, designed to thoroughly expose the abilities of Direct3D 11-class hardware, such as tessellation.

Hardware support: Nvidia GeForce 400 series and newer, AMD Radeon HD 5000 series and newer (FP64 shaders implemented by emulation on some TeraScale GPUs), Intel HD Graphics in Intel Ivy Bridge processors and newer.[69]

OpenGL 4.1

[edit]Release date: July 26, 2010

- Minimum "maximum texture size" is 16,384 × 16,384 for GPUs implementing this specification.[70]

- Improved compatibility for OpenGL ES 2.0[71]

- Multiple Viewports for the same rendering surface, or one per surface.[72]

Hardware support: Nvidia GeForce 400 series and newer, AMD Radeon HD 5000 series and newer (FP64 shaders implemented by emulation on some TeraScale GPUs), Intel HD Graphics in Intel Haswell processors and newer[69] (Linux Mesa: Ivy Bridge and newer). Additionally, this is the last core profile supported by Apple macOS.

OpenGL 4.2

[edit]Release date: August 8, 2011[56]

- Support for shaders with atomic counters and load-store-atomic read-modify-write operations to one level of a texture

- Drawing multiple instances of data captured from GPU vertex processing (including tessellation), to enable complex objects to be efficiently repositioned and replicated

- Support for modifying an arbitrary subset of a compressed texture, without having to re-download the whole texture to the GPU for significant performance improvements

Hardware support: Nvidia GeForce 400 series and newer, AMD Radeon HD 5000 series and newer (FP64 shaders implemented by emulation on some TeraScale GPUs), and Intel HD Graphics in Intel Haswell processors and newer.[69] (Linux Mesa: Ivy Bridge and newer)

OpenGL 4.3

[edit]Release date: August 6, 2012[57]

- Compute shaders leveraging GPU parallelism within the context of the graphics pipeline

- Shader storage buffer objects, allowing shaders to read and write buffer objects like image load/store from 4.2, but through the language rather than function calls.

- Image format parameter queries

- ETC2/EAC texture compression as a standard feature

- Full compatibility with OpenGL ES 3.0 APIs

- Debug abilities to receive debugging messages during application development

- Texture views to interpret textures in different ways without data replication

- Increased memory security and multi-application robustness

Hardware support: AMD Radeon HD 5000 series and newer (FP64 shaders implemented by emulation on some TeraScale GPUs), Intel HD Graphics in Intel Haswell processors and newer.[69] (Linux Mesa: Ivy Bridge without stencil texturing, Haswell and newer), Nvidia GeForce 400 series and newer. VIRGL Emulation for virtual machines supports 4.3+ with Mesa 20.

OpenGL 4.4

[edit]Release date: July 22, 2013[59]

- Enforced buffer object usage controls

- Asynchronous queries into buffer objects

- Expression of more layout controls of interface variables in shaders

- Efficient binding of multiple objects simultaneously

Hardware support: AMD Radeon HD 5000 series and newer (FP64 shaders implemented by emulation on some TeraScale GPUs), Intel HD Graphics in Intel Broadwell processors and newer (Linux Mesa: Haswell and newer),[73] Nvidia GeForce 400 series and newer,[74] Tegra K1.

OpenGL 4.5

[edit]Release date: August 11, 2014[17][60]

- Direct State Access (DSA) – object accessors enable state to be queried and modified without binding objects to contexts, for increased application and middleware efficiency and flexibility.[75]

- Flush Control – applications can control flushing of pending commands before context switching – enabling high-performance multithreaded applications;

- Robustness – providing a secure platform for applications such as WebGL browsers, including preventing a GPU reset affecting any other running applications;

- OpenGL ES 3.1 API and shader compatibility – to enable the easy development and execution of the latest OpenGL ES applications on desktop systems.

Hardware support: AMD Radeon HD 5000 series and newer (FP64 shaders implemented by emulation on some TeraScale GPUs), Intel HD Graphics in Intel Broadwell processors and newer (Linux Mesa: Haswell and newer), Nvidia GeForce 400 series and newer,[74] Tegra K1, and Tegra X1.[76][77]

OpenGL 4.6

[edit]Release date: July 31, 2017[17][9][61]

- more efficient, GPU-sided, geometry processing

- more efficient shader execution (AZDO)

- more information through statistics, overflow query and counters

- higher performance through no error handling contexts

- clamping of polygon offset function, solves a shadow rendering problem

- SPIR-V shaders

- Improved anisotropic filtering

Hardware support: AMD Radeon HD 7000 series and newer (FP64 shaders implemented by emulation on some TeraScale GPUs), Intel Skylake and newer, Nvidia GeForce 400 series and newer.[74]

Driver support:

- Mesa 19.2 on Linux supports OpenGL 4.6 for Intel Broadwell and newer.[78] Mesa 20.0 supports AMD Radeon GPUs,[79] while support for Nvidia Kepler+ is in progress. Zink as Emulation Driver with 21.1 and software driver LLVMpipe also support with Mesa 21.0.

- AMD Adrenalin 18.4.1 Graphics Driver on Windows 7 SP1, 10 version 1803 (April 2018 update) for AMD Radeon HD 7700+, HD 8500+ and newer. Released April 2018.[80][81]

- Intel 26.20.100.6861 graphics driver on Windows 10. Released May 2019.[82][83]

- NVIDIA GeForce 397.31 Graphics Driver on Windows 7, 8, 10 x86-64 bit only, no 32-bit support. Released April 2018[84]

Alternative implementations

[edit]Apple deprecated OpenGL in iOS 12 and macOS 10.14 Mojave in favor of Metal, but it is still available as of macOS 14 Sonoma (including on Apple silicon devices).[85] The latest version supported for OpenGL is 4.1 from 2011.[86][87] A proprietary library from Molten – authors of MoltenVK – called MoltenGL, can translate OpenGL calls to Metal.[88]

There are several projects that attempt to implement OpenGL on top of Vulkan. The Vulkan backend for Google's ANGLE achieved OpenGL ES 3.1 conformance in July 2020.[89] The Mesa3D project also includes such a driver, called Zink.[90]

Microsoft's Windows 11 on Arm added support for OpenGL 3.3 via GLon12, an open source OpenGL implementation on top DirectX 12 via Mesa Gallium.[91][92][93]

Vulkan

[edit]Vulkan, formerly named the "Next Generation OpenGL Initiative" (glNext),[94][95] is a ground-up redesign effort to unify OpenGL and OpenGL ES into one common API that will not be backwards compatible with existing OpenGL versions.[96][97][98]

The initial version of Vulkan API was released on February 16, 2016.

See also

[edit]- ARB assembly language – OpenGL's legacy low-level shading language

- Direct3D – main competitor of OpenGL

- Glide (API) – a graphics API once used on 3dfx Voodoo cards

- Metal (API) – a graphics API for iOS, macOS, tvOS, watchOS

- OpenAL – cross-platform audio library, designed to resemble OpenGL

- OpenGL ES – OpenGL for embedded systems

- OpenSL ES – API for audio on embedded systems, developed by the Khronos Group

- OpenVG – API for accelerated 2D graphics, developed by the Khronos Group

- RenderMan Interface Specification (RISpec) – Pixar's open API for photorealistic off-line rendering

- VOGL – a debugger for OpenGL

- Vulkan – low-overhead, cross-platform 2D and 3D graphics API, the "next generation OpenGL initiative"

- Graphics pipeline

- WebGL

- WebGPU

Notes

[edit]- ^ ARB and EXT are OpenGL extension identifiers. Each extension is associated with a short identifier based on the name of the company which developed it, e.g. NV for Nvidia. If multiple vendors agree to implement the same functionality using the same API, a shared extension may be released using the identifier EXT. In such cases, it could also happen that the Khronos Group's Architecture Review Board gives the extension their explicit approval, in which case the identifier ARB is used.[8]

- ^ optional, made core in OpenGL 4.3

References

[edit]- ^ "Khronos Releases OpenGL 4.6 with SPIR-V Support".

- ^ Lextrait, Vincent (January 2010). "The Programming Languages Beacon, v10.0". Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ "Products: Software: OpenGL: Licensing and Logos". SGI. Archived from the original on November 1, 2012. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ "The OpenGL Graphics System: A Specification" (PDF). 4.0 (Core Profile). March 11, 2010.

- ^ "SGI – OpenGL Overview". Archived from the original on October 31, 2004. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- ^ Peddie, Jon (July 2012). "Who's the Fairest of Them All?". Computer Graphics World. Retrieved May 30, 2018.

- ^ "OpenGL ARB to Pass Control of OpenGL Specification to Khronos Group". The Khronos Group. July 31, 2006. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ "How to Create Khronos API Extensions". Khronos Group. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Khronos Releases OpenGL 4.6 with SPIR-V Support". The Khronos Group Inc. July 31, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "Vulkan, OpenGL, and OpenGL ES SIGGRAPH 2017: No plan for new core version for OpenGL ES" (PDF). Khronos Group. 2017.

- ^ "The Future of OpenGL (forum discussion)". Khronos Group. 2020.

- ^ "Khronos News Archives". Khronos Group. November 28, 2022.

- ^ "Khronos Blog". Khronos Group. November 28, 2022.

- ^ "GLSL_NV_ray_tracing". GitHub.

- ^ "GL_NV_mesh_shader". GitHub.

- ^ "Khronos Membership Overview and FAQ". Khronos.org. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "Khronos OpenGL Registry". Khronos Group. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "OpenGL - The Industry's Foundation for High Performance Graphics". The Khronos Group. July 19, 2011. Retrieved March 18, 2021.

- ^ "A list of GLUT alternatives, maintained by". Khronos Group. Retrieved May 2, 2013.

- ^ "Related toolkits and APIs". www.opengl.org. OpenGL. Retrieved October 8, 2014.

- ^ "IRIS GL, SGI's property".

- ^ Kilgard, Mark (2008). "OpenGL Prehistory: IRIS GL (slide)". www.slideshare.net.

- ^ "Preface: What is OpenGL?". OpenGLBook. Retrieved December 31, 2024.

- ^ "Appendix B. Differences Between OpenGL and IRIS GL". tech-pubs.net. Retrieved October 3, 2025.

- ^ "Creation of the OpenGL ARB". Archived from the original on February 22, 2007. Retrieved February 16, 2007.

- ^ "End of OpenGL++". Khronos Group.

- ^ "Top Game Developers Call on Microsoft to Actively Support OpenGL". Next Generation. No. 32. Imagine Media. August 1997. p. 17.

- ^ "Announcement of Fahrenheit". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007.

- ^ "Members of Fahrenheit. 1998". Computergram International. 1998. Archived from the original on October 5, 2007.

- ^ "End of Fahrenheit". The Register.

- ^ "OpenGL ARB to pass control of OpenGL specification to Khronos Group". Khronos press release. July 31, 2006.

- ^ "OpenGL ARB to Pass Control of OpenGL Specification to Khronos Group". AccessMyLibrary Archive.

- ^ "OpenGL Celebrates Its 30th Birthday". www.phoronix.com. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ "OpenGL is not dead, long live Vulkan". The Accidental Astronomer. April 9, 2023. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ Smith, Ryan (June 5, 2018). "Apple Deprecates OpenGL Across All OSes; Urges Developers to use Metal". www.anandtech.com. Purch. Archived from the original on June 6, 2018. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- ^ "GLQuake". Quake Wiki.

- ^ eTeknix.com (July 29, 2016). "Doom OpenGL VS Vulkan Graphics Performance Analysis". eTeknix. Retrieved December 7, 2024.

- ^ "Doom Wiki: id Tech 7". Retrieved October 26, 2021.

- ^ "Technology Licensing: id Tech 2". Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved September 17, 2008.

- ^ Dawe, Liam (March 7, 2023). "Dota 2 removes OpenGL support, new hero Muerta now live, big update due in April". GamingOnLinux. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ "Jet Set Vulkan : Reflecting on the move to Vulkan".

- ^ "NVIDIA DLSS SDK". github.com/NVIDIA/DLSS.

- ^ "AMD FidelityFX-SDK". github.com/GPUOpen-LibrariesAndSDKs/FidelityFX-SDK.

- ^ "Magma: Overview". fuchsia.dev. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- ^ Kilgard, Mark J. (2001). OpenGL programming for the X Window System. Graphics programming (6. print ed.). Boston, Mass. Munich: Addison-Wesley. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-201-48359-8.

- ^ "The OpenGL Graphics System: A Specification" (PDF). 1.1. March 4, 1997.

- ^ Astle, Dave (April 1, 2003). "Moving Beyond OpenGL 1.1 for Windows". gamedev.net. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ Isorna, J.M. (2015). Simulación visual de materiales : teoría, técnicas, análisis de casos. UPC Grau. Arquitectura, urbanisme i edificació (in Spanish). Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya. p. 191. ISBN 978-84-9880-564-2. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ a b c "The OpenGL Graphics System: A Specification" (PDF). 2.1. December 1, 2006.

- ^ "Point Primitive".

- ^ "The OpenGL Graphics System: A Specification" (PDF). 3.0. September 23, 2008.

- ^ "The OpenGL Graphics System: A Specification" (PDF). 3.1. May 28, 2009.

- ^ "The OpenGL Graphics System: A Specification" (PDF). 3.2 (Core Profile). December 7, 2009.

- ^ "Khronos Unleashes Cutting-Edge, Cross-Platform Graphics Acceleration with OpenGL 4.0". March 11, 2010.

- ^ "Khronos Drives Evolution of Cross-Platform 3D Graphics with Release of OpenGL 4.1 Specification". July 26, 2010.

- ^ a b "Khronos Enriches Cross-Platform 3D Graphics with Release of OpenGL 4.2 Specification". The Khronos Group. August 8, 2011.

- ^ a b "Khronos Releases OpenGL 4.3 Specification with Major Enhancements". August 6, 2012.

- ^ "Khronos Releases OpenGL 4.3 Specification with Major Enhancements". August 6, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Khronos Releases OpenGL 4.4 Specification". July 22, 2013.

- ^ a b "Khronos Group Announces Key Advances in OpenGL Ecosystem – Khronos Group Press Release". The Khronos Group Inc. August 10, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Kessenich, John; Baldwin, Dave. "The OpenGL Shading Language, Version 4.60.7". The Khronos Group Inc. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Abi-Chahla, Fedy (September 16, 2008). "OpenGL 3 (3DLabs And The Evolution Of OpenGL)". Tom's Hardware. Retrieved October 24, 2010.

- ^ "The OpenGL Graphics System: A Specification" (PDF). 2.0. October 22, 2004.

- ^ "OpenGL ARB announces an update on OpenGL 3.0". October 30, 2007. Archived from the original on November 7, 2007. Retrieved October 31, 2007.

- ^ "OpenGL 3.0 Released, Developers Furious – Slashdot". Tech.slashdot.org. August 11, 2008. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ "OpenGL BOF went over well, no pitch forks seen".

- ^ "The Industry Standard for High Performance Graphics". OpenGL. August 18, 2008. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "NVIDIA provides early OpenGL 3.0 driver now".

- ^ a b c d "Intel Iris and HD Graphics Driver for Windows 7/8/8.1 64bit". Intel Download Center. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015.

- ^ "Expected maximum texture size - Graphics and GPU Programming". GameDev.net.

- ^ "OpenGL 4.1 (Core Profile) - July 25, 2010" (PDF). Khronos.org.

- ^ "History of OpenGL - OpenGL Wiki". Khronos.org.

- ^ "Intel Skylake-S CPUs and 100-series Chipsets Detailed in Apparent Leak". NDTV Gadgets. April 17, 2015.

- ^ a b c Larabel, Michael (July 31, 2017). "NVIDIA Releases 381.26.11 Linux Driver With OpenGL 4.6 Support". Phoronix.

- ^ "OpenGL 4.5 released—with one of Direct3D's best features". Ars Technica. August 11, 2014. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ "SG4121: OpenGL Update for NVIDIA GPUs". Ustream. Archived from the original on May 17, 2015. Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ Kilgard, Mark (August 12, 2014). "OpenGL 4.5 Update for NVIDIA GPUs". Retrieved April 17, 2015.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (August 21, 2019). "Intel's OpenGL Linux Driver Now Has OpenGL 4.6 Support For Mesa 19.2". Phoronix.

- ^ Larabel, Michael (November 27, 2019). "AMD's RadeonSI Driver Finally Enables OpenGL 4.6". Phoronix.

- ^ "AMD Adrenalin 18.4.1 Graphics Driver Released (OpenGL 4.6, Vulkan 1.1.70) – Geeks3D". www.geeks3d.com. May 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "Radeon Software Adrenalin Edition 18.4.1 Release Notes". support.amd.com. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "Intel Graphics Driver 25.20.100.6861 Released (OpenGL 4.6 + Vulkan 1.1.103) | Geeks3D". May 16, 2019. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "Windows 10 DCH Drivers". Intel DownloadCenter. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ "NVIDIA GeForce 397.31 Graphics Driver Released (OpenGL 4.6, Vulkan 1.1, RTX, CUDA 9.2) – Geeks3D". www.geeks3d.com. April 25, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "Apple Developer Documentation". developer.apple.com.

- ^ Cunningham, Andrew (October 7, 2019). "macOS 10.15 Catalina: The Ars Technica review". Ars Technica.

- ^ Axon, Samuel (June 6, 2018). "The end of OpenGL support, plus other updates Apple didn't share at the keynote". Ars Technica. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Vulkan, and faster OpenGL ES, on iOS and macOS". Molten. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ The ANGLE Project Authors (October 14, 2020). "google/angle: A conformant OpenGL ES implementation for Windows, Mac, Linux, iOS and Android". GitHub. Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- ^ "Zink". The Mesa 3D Graphics Library latest documentation.

- ^ "State of Windows on Arm64: a high-level perspective". Chips and Cheese. March 13, 2022. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ^ "Introducing OpenCL and OpenGL on DirectX". Collabora | Open Source Consulting. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ^ "Deep dive into OpenGL over DirectX layering". Collabora | Open Source Consulting. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ^ Dingman, Hayden (March 3, 2015). "Meet Vulkan, the powerful, platform-agnostic gaming tech taking aim at DirectX 12". PC World. Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ^ Bright, Peter (March 3, 2015). "Khronos unveils Vulkan: OpenGL built for modern systems". Ars Technica. Retrieved March 3, 2015.

- ^ "Khronos Announces Next Generation OpenGL Initiative". AnandTech. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ^ Anthony, Sebastian (August 11, 2014). "OpenGL 4.5 released, next-gen OpenGL unveiled: Cross-platform Mantle killer, DX12 competitor". ExtremeTech. Retrieved August 20, 2014.

- ^ "Khronos Publishes Its Slides About OpenGL-Next". Phoronix. Retrieved August 22, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- Shreiner, Dave; Sellers, Graham; et al. (March 30, 2013). OpenGL Programming Guide: The Official Guide to Learning OpenGL. Version 4.3 (8th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-77303-6.

- Sellers, Graham; Wright, Richard S.; Haemel, Nicholas (July 31, 2013). OpenGL SuperBible: Comprehensive Tutorial and Reference (6th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-90294-8.

- Rost, Randi J. (July 30, 2009). OpenGL Shading Language (3rd ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-63763-5.

- Lengyel, Eric (2003). The OpenGL Extensions Guide. Charles River Media. ISBN 1-58450-294-0.

- OpenGL Architecture Review Board; Shreiner, Dave (2004). OpenGL Reference Manual: The Official Reference Document to OpenGL. Version 1.4. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-321-17383-X.

- OpenGL Architecture Review Board; Shreiner, Dave; et al. (2006). OpenGL Programming Guide: The Official Guide to Learning OpenGL. Version 2 (5th ed.). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-321-33573-2.

External links

[edit]- Official website

- OpenGL Overview and OpenGL.org's Wiki with more information on OpenGL Language bindings

- SGI's OpenGL website

- Khronos Group, Inc.

- [1] OpenGL lectures by Tom Duff (Pixar Animation) and George Ledin Jr (Sonoma State University)

OpenGL

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Purpose

OpenGL is a royalty-free, cross-language, cross-platform application programming interface (API) specification maintained by the Khronos Group, designed for rendering 2D and 3D vector graphics through hardware acceleration on graphics processing units (GPUs).[1] It provides a standardized way for developers to access low-level graphics hardware features without being tied to specific vendors or operating systems, enabling portable graphics applications across diverse platforms including PCs, workstations, and embedded systems.[1] The primary purpose of OpenGL is to facilitate real-time rendering in a wide array of applications, such as video games, computer-aided design (CAD), scientific visualization, and virtual reality simulations.[1] By abstracting complex GPU operations, it supports efficient processing of graphical data through a high-level rendering pipeline that transforms and displays vector-based imagery.[5] Key benefits include hardware independence via multi-vendor support, which allows applications to run consistently across different GPU implementations, and an immediate-mode paradigm that simplifies development by directly issuing drawing commands without managing persistent scene objects.[1][5] This approach, combined with abstractions for advanced GPU capabilities like shading and texturing, makes OpenGL suitable for performance-critical tasks while remaining accessible to developers.[1] Representative use cases demonstrate its versatility: in video games, it enabled hardware-accelerated rendering in titles like Quake through the GLQuake port developed by id Software; flight simulators leverage it for realistic 3D terrain and cockpit visualizations; and medical imaging applications use it to render volumetric data for diagnostic purposes.[6][7][8]Fundamental Concepts

OpenGL's fundamental concepts revolve around a set of core objects and processing stages that enable efficient graphics rendering. These objects serve as the primary mechanisms for data storage and management within the graphics pipeline. Buffers, particularly Vertex Buffer Objects (VBOs), are used to store vertex data such as positions, colors, and normals in server-side memory, allowing for optimized data transfer and reuse during rendering.[2] Textures provide multidimensional arrays of image data (texels) that can be sampled during shading to add surface details, supporting formats like 2D, 3D, and cube maps.[2] Framebuffers encapsulate render targets, combining attachments for color, depth, and stencil buffers to direct output to off-screen surfaces or the default window.[2] Programs represent the compilation and linkage of shader objects, forming executable code for programmable stages like vertex and fragment processing.[2] Vertex processing begins with vertices defined as points in space, each associated with attributes such as position (typically a 3D vector), color, and normal vector, which are fetched from bound buffers or arrays.[2] These attributes undergo transformation through matrix multiplications in the vertex shader: the model matrix positions the object in world space, the view matrix orients it relative to the camera, and the projection matrix maps it to normalized device coordinates, culminating in the model-view-projection (MVP) transformation that prepares vertices for clipping and perspective division.[2] Following vertex processing, fragment processing involves rasterization, where primitives are converted into fragments—potential pixels with interpolated attributes—based on their coverage in the viewport.[2] Per-pixel shading then occurs in the fragment shader, computing final colors and depth values for each fragment using interpolated data, texture samples, and lighting calculations to determine the rendered output.[2] A key element of vertex transformation is the perspective projection matrix, which simulates depth by scaling coordinates based on distance from the viewer. The standard symmetric form, derived from parameters like vertical field of view (in radians), aspect ratio , near plane , and far plane , is given by: This matrix maps eye-space coordinates to clip space, where the reciprocal of the homogeneous -coordinate enables perspective foreshortening during the subsequent divide.[2] Rendering is initiated through draw calls, which specify primitives to generate from vertex data. TheglDrawArrays function renders a sequence of primitives—such as points (GL_POINTS), lines (GL_LINES), or triangles (GL_TRIANGLES)—directly from sequential array elements, using parameters for mode, starting index, and count.[2] In contrast, glDrawElements uses an index buffer to reference vertices non-sequentially, promoting efficiency for shared vertices in meshes, with parameters including mode, count, index type (e.g., unsigned int), and offset into the element array.[2]

History

Origins and Early Development

OpenGL's development began in 1991 at Silicon Graphics, Inc. (SGI), where it was conceived as a successor to the company's proprietary IRIS GL graphics library, aiming to create a more portable and standardized interface for 3D graphics programming.[9] The primary architects, Mark Segal and Kurt Akeley, focused on achieving platform independence by abstracting hardware-specific details from IRIS GL, enabling the API to target UNIX workstations and other systems without tying applications to SGI's hardware ecosystem.[10] This design emphasized high-performance rendering for interactive 2D and 3D applications while maintaining a simple programming model that allowed direct access to graphics hardware capabilities across diverse windowing systems, such as the X Window System.[10] SGI released OpenGL 1.0 on June 30, 1992, marking its formal introduction as an open, royalty-free standard.[3] To ensure collaborative evolution and broad industry buy-in, SGI led the formation of the OpenGL Architecture Review Board (ARB) in 1992, an independent consortium responsible for defining conformance tests, approving specifications, and advancing the standard.[11] Founding members included SGI, Microsoft, and IBM, among others, reflecting early support from key players in computing and graphics hardware.[11] The ARB's structure facilitated extensions and updates while preserving backward compatibility, setting the foundation for OpenGL's role as a cross-platform API.[3] OpenGL 1.1 followed in March 1997, introducing features like texture objects to improve efficiency in managing texture data for rendering, which addressed growing demands for more complex visual applications.[12] By 2006, to promote non-profit, open governance, the ARB transferred control of the OpenGL specification to the Khronos Group, transforming it into the OpenGL Working Group and ensuring continued royalty-free development.[13]Industry Support and Adoption

The OpenGL Architecture Review Board (ARB) was established in 1992 by Silicon Graphics Inc. (SGI) along with initial members including Intel, Microsoft, Compaq, Digital Equipment Corporation, Evans & Sutherland, and IBM to govern the specification's development and ensure cross-vendor compatibility.[14] NVIDIA joined as an auxiliary member in September 1999 and was elected to permanent membership in October 2003, reflecting its growing influence in consumer graphics hardware.[15][16] ATI Technologies (later acquired by AMD) became an auxiliary member in 1999 and a permanent member in January 2002, expanding the board's representation of PC graphics vendors.[17] In 2000, the ARB's efforts contributed to the formation of the Khronos Group, which absorbed oversight of OpenGL in 2006, with founding members including Intel, NVIDIA, ATI, SGI, and Sun Microsystems to broaden standards across multimedia APIs.[18] Key adoption milestones included integration into major operating systems, beginning with the Mesa 3D graphics library project initiated in August 1993 by Brian Paul to provide an open-source OpenGL-compatible implementation for Linux and other Unix-like systems.[19] Microsoft introduced OpenGL support in Windows NT in 1995 and extended it to Windows 95 via the Win32 API, enabling broader accessibility for PC applications through installable client drivers (ICDs). Apple released OpenGL support for the Macintosh platform on May 10, 1999, compatible with Mac OS 8.1 and later, providing hardware-accelerated rendering through its graphics drivers, with full integration into Mac OS X (later macOS) starting in 2001 to support professional and creative workflows.[20] A primary challenge in OpenGL's adoption was fragmentation caused by vendor-specific extensions, which allowed companies like NVIDIA and ATI to introduce proprietary features ahead of standardization, leading to inconsistent application behavior across hardware.[21] The ARB addressed this by promoting widely adopted extensions into core specifications—such as multisampling in OpenGL 1.3 (2001)—to unify functionality and reduce developer overhead in handling multiple variants.[21] OpenGL's impact extended across industries, establishing dominance in PC gaming where it competed with Microsoft's Direct3D, powering titles like Quake III Arena (1999) for cross-platform rendering while Direct3D captured Windows-exclusive market share.[22] In computer-aided design (CAD), software like AutoCAD relied on OpenGL for hardware-accelerated 3D modeling and visualization, with Autodesk optimizing drivers for professional graphics cards to enhance performance in engineering applications.[23] Supercomputing visualization at NASA leveraged OpenGL for rendering complex datasets, as seen in systems like the Ames Research Center's SGI Reality Center (2004), which used OpenGL to display high-resolution simulations of aerospace phenomena on multi-wall displays.[24] By the early 2000s, OpenGL had achieved widespread hardware support, becoming the de facto standard for 3D graphics on professional and consumer GPUs, driven by its portability and ecosystem maturity.Design and Architecture

Core Principles

OpenGL is fundamentally designed as a state machine, where the graphics library maintains a collection of global state variables that control the processing and rendering of graphics primitives into the framebuffer. These state variables, such as the current color, matrix mode, and texture bindings, are modified by API calls and persist across subsequent operations until explicitly changed, influencing how drawing commands are executed. For instance, theglColor3f function sets the current RGBA color used for vertices or pixels, while glMatrixMode selects the active matrix stack (e.g., modelview or projection) for transformation operations. This paradigm ensures that rendering behavior is determined by the cumulative effect of state-setting commands, as articulated in the specification: "We view OpenGL as a state machine that controls a set of specific drawing operations."[5]

A core principle of OpenGL is its cross-platform abstraction, which provides a standardized API that hides underlying hardware differences and operating system variations, thereby promoting portability across diverse environments. By defining a consistent interface for graphics operations, OpenGL enables applications to render 2D and 3D graphics without modification on platforms ranging from PCs and workstations to mobile devices and supercomputers, regardless of the specific GPU or windowing system. As described by the Khronos Group, "OpenGL is window-system and operating-system independent as well as network-transparent," allowing developers to leverage the latest hardware features through a unified abstraction layer.[1]

OpenGL emphasizes an immediate mode rendering approach for its simplicity, where geometry is specified directly via commands that are executed on-the-fly, though it has evolved to support retained modes for greater efficiency. In immediate mode, developers issue sequences like glBegin(GL_TRIANGLES); glVertex3f(...); glEnd() to define and render primitives in real time, making it intuitive for straightforward applications but inefficient for complex scenes due to repeated command overhead. Retained modes, introduced with vertex arrays in OpenGL 1.1, store geometry data in client-side arrays or buffer objects for batch processing, as with glVertexPointer followed by glDrawArrays, reducing calls and enabling better GPU utilization; the specification notes that "Vertex arrays allow an application to specify multiple geometric primitives in one call to the GL." This shift prioritizes immediate mode's ease while providing retained options to handle modern rendering demands.[5]

Error handling in OpenGL follows a non-fatal model, where detectable errors set an error flag without halting execution or altering state, allowing applications to continue while checking for issues. The primary mechanism is glGetError, which returns the oldest error code (e.g., GL_INVALID_OPERATION or GL_OUT_OF_MEMORY) and clears the flag, requiring repeated calls to retrieve all pending errors; the function's description states, "Each detectable error is assigned a numeric code and symbolic name. When an error occurs, the error flag is set." In later core profiles, such as OpenGL 4.3, the KHR_debug extension—promoted to core—enhances this with debug output callbacks for detailed messaging on errors, performance warnings, and other events.[25][26]

The threading model of OpenGL is not inherently multi-threaded, with each context bound to a single thread at a time to ensure sequential command processing and avoid race conditions. Only the thread holding the current context can issue OpenGL commands; attempting otherwise leads to undefined behavior, as the specification clarifies: "An OpenGL context may not be current to more than one thread at a time." Parallelism is supported through context sharing, where multiple contexts across threads can share objects like textures, buffers, and programs within a share group, enabling distributed workloads such as asset loading in background threads while requiring explicit synchronization via fences or barriers. This design, as noted in the core profile, allows "multiple rendering contexts [to] share an address space or a subset of it" to facilitate controlled concurrency.[2]

Rendering Pipeline

The OpenGL rendering pipeline is a sequence of processing stages that converts vertex data representing 3D primitives into a final rasterized image in the framebuffer.[2] This pipeline operates as a state machine, where rendering commands invoke the stages in order, with configurable states influencing behavior at each step.[2] The core stages, from input to output, are vertex fetch and shading, optional tessellation processing (control shader, primitive generation, and evaluation shader), optional geometry shading, primitive assembly and clipping, rasterization, fragment shading, per-fragment operations (including per-sample operations), and framebuffer operations (output merging).[2] Vertex fetch retrieves attribute data, such as positions, normals, and colors, from vertex buffer objects or client arrays, assembling per-vertex inputs for subsequent processing.[2] The vertex shader stage then transforms these inputs programmatically, computing outputs like clip-space positions (gl_Position) and passing through or generating other attributes.[2] If enabled, tessellation processing follows: the tessellation control shader determines patch properties and tessellation levels, fixed-function primitive generation subdivides patches into basic primitives, and the tessellation evaluation shader computes positions and attributes for the generated vertices. Optionally, a geometry shader can then process entire primitives, emitting zero or more new primitives with modified or additional vertices. Following these, primitive assembly groups the processed vertices into geometric primitives (e.g., points, lines, or triangles) based on the specified drawing mode, such as GL_TRIANGLES, with clipping applied to remove portions outside the view volume.[2] Rasterization converts these primitives into fragments by interpolating attributes across the primitive's interior, generating coverage data for pixels.[2] The fragment shader processes each fragment, computing final colors and other outputs using interpolated inputs.[2] Per-fragment operations apply fixed-function tests, including scissor, sample coverage, depth/stencil, and blending, while framebuffer operations resolve multisample data and merge results into the framebuffer attachments.[2] In legacy fixed-function pipelines, stages prior to rasterization handled transformations, lighting, and texturing automatically without shaders.[2] Lighting computations used models like Phong, calculating per-vertex illumination intensity as the sum of ambient, diffuse, and specular components, given by: where is the ambient coefficient, the diffuse coefficient, the specular coefficient, the surface normal, the light direction, the reflection vector, the view direction, and the shininess exponent.[2] Texturing applied fixed mappings from texture units, with environment mapping and multitexturing for combining multiple layers via modulation or other modes.[2] These fixed operations are deprecated in core profiles but remain available in compatibility modes for backward compatibility.[2] Programmable stages, introduced via shaders written in the [OpenGL Shading Language](/page/OpenGL_Shading Language) (GLSL), allow custom processing at vertex, tessellation control, tessellation evaluation, geometry, and fragment stages, replacing fixed-function logic with user-defined computations for transformations, lighting, and effects.[2] These shaders handle per-vertex or per-primitive operations (vertex, tessellation, geometry) or per-fragment coloring (fragment), enabling flexible material responses and procedural generation.[2] Additionally, compute shaders provide a separate dispatch mechanism for general-purpose GPU computing, outside the rendering pipeline but using the same GLSL framework.[2] Transform feedback provides a mechanism to capture outputs from vertex, tessellation, or geometry shaders into buffer objects during rendering, allowing reuse of transformed primitive data without reprocessing, such as for particle simulations or geometry caching.[2] Back-face culling discards primitives oriented away from the viewer during primitive assembly, determined by vertex winding order (counterclockwise for front-facing by default), reducing unnecessary rasterization.[2] Depth testing, part of per-fragment operations, employs a z-buffer algorithm to resolve visibility: for each fragment, the incoming depth value is compared against the buffer's stored depth using a configurable function (e.g., GL_LESS), discarding the fragment if it fails and updating the buffer if it passes.[2] This hidden surface removal ensures correct depth ordering without explicit sorting of primitives.[2]Extension Mechanism

OpenGL's extension mechanism allows the API to evolve by incorporating new functionality without disrupting backward compatibility with existing applications. This modular approach enables hardware vendors and standards bodies to introduce features that can later be integrated into core specifications, ensuring that OpenGL remains adaptable to advancing graphics hardware capabilities.[2] Extensions are classified into three primary types: vendor-specific, ARB (Architecture Review Board), and KHR (Khronos). Vendor-specific extensions, such as NVIDIA's NV_gpu_program series for advanced programmable shading, are developed by individual hardware manufacturers to expose proprietary hardware features. ARB extensions, managed by the Khronos OpenGL ARB Working Group, represent collaboratively developed enhancements with broad industry support, such as GL_ARB_multitexture for multiple texture units.[2] KHR extensions, approved jointly by the ARB and Khronos OpenGL ES working groups, focus on cross-platform portability, exemplified by GL_KHR_debug for standardized debugging and validation callbacks.[2] To determine which extensions are supported by a given OpenGL implementation, applications query the current context using specific API calls. The traditional method retrieves a space-separated string of extension names via glGetString(GL_EXTENSIONS).[2] In modern OpenGL versions (3.0 and later), this approach is deprecated in favor of an indexed query mechanism: first, obtain the number of extensions with glGetIntegerv(GL_NUM_EXTENSIONS, &count), then iterate using glGetStringi(GL_EXTENSIONS, index) for each name from 0 to count-1, which provides more reliable parsing and avoids buffer overflow risks.[2] On Windows platforms, wglGetExtensionsStringARB can query WGL-specific extensions relevant to windowing, complementing OpenGL queries. Loading extension functions requires manual resolution since they are not part of the core API entry points. Applications use the platform-independent glGetProcAddress function (often accessed via extensions like WGL_ARB_get_proc_address on Windows or GLX_ARB_get_proc_address on Linux) to dynamically obtain pointers to extension-specific functions, such as those in NV_gpu_program.[2] This process allows code to conditionally enable advanced features only if supported, maintaining portability across diverse hardware. The OpenGL Extension Registry, maintained by the Khronos Group at https://registry.khronos.org/OpenGL/, serves as the authoritative repository for all extension specifications, including detailed descriptions, header files (e.g., glext.h), and conformance requirements.[27] Developers reference this registry to implement and verify extensions, ensuring adherence to standardized naming conventions and semantics.[27] Extensions undergo a lifecycle managed by the Khronos working groups, where successful ones are promoted to core API features in subsequent OpenGL versions, such as GL_ARB_multitexture advancing to OpenGL 1.3.[2] Conversely, less adopted or superseded extensions may be marked as deprecated, potentially removed from the core profile (e.g., immediate mode rendering in OpenGL 3.1), though they often persist in compatibility profiles to preserve legacy support.[2] This promotion and deprecation process, outlined in specification appendices, balances innovation with stability.[2]Standards and Documentation

Specifications and Versions

OpenGL specifications are maintained by the Khronos Group and define the API's behavior, including mandatory features in the core profile and optional legacy support in the compatibility profile. The core profile, introduced in OpenGL 3.2, mandates only modern, programmable features, excluding deprecated fixed-function elements to encourage forward-compatible development. In contrast, the compatibility profile combines core features with legacy functionality for backward compatibility, allowing applications to use both modern and older APIs. Forward-compatible contexts restrict deprecated features entirely, ensuring applications can only access non-deprecated elements to promote future-proof code.[2] The release process for OpenGL specifications is overseen by the OpenGL Architecture Review Board (ARB), which votes on major updates every few years, incorporating promoted extensions and new features into the core API. Minor updates occur irregularly, often several times per year for current versions, to address issues, clarify language, or integrate fixes based on developer feedback and backlog. Historically, major releases like OpenGL 3.2, 4.0, and 4.6 followed a cadence of annual or biennial updates in the late 2000s and 2010s, driven by ARB consensus to balance innovation with stability. Extensions continue to evolve the API, with recent additions like GL_EXT_mesh_shader (ratified October 2025) enabling task and mesh shaders for efficient primitive processing.[28][29][30][31] OpenGL provides backward compatibility guarantees within major versions, meaning applications written for an earlier minor version in the same major series will function without modification on later implementations. However, starting with OpenGL 3.1, deprecation lists were introduced to phase out obsolete features, such as the fixed-function pipeline, which became optional in core profiles from 3.1 onward and unavailable in forward-compatible contexts. This approach allows vendors to evolve hardware support while minimizing disruption for legacy code in compatibility profiles.[2][32] Vendor conformance to OpenGL specifications is verified through the Khronos Conformance Process, which requires passing a suite of automated tests to certify implementations for specific versions and profiles. Adopters, including hardware vendors, must submit test results to a Khronos review committee for validation, granting use of the OpenGL trademark upon approval. This process ensures consistent behavior across platforms.[33][34][35] The evolution of OpenGL headers reflects the API's growth beyond its initial design, with the originalgl.h providing declarations only up to version 1.1, necessitating extensions in glext.h for later features. Modern development avoids direct inclusion of gl.h or glext.h due to their limitations in supporting runtime function loading for versions beyond 1.1, instead relying on loader libraries like Glad or GLEW. These loaders generate context-specific headers from official Khronos specifications (e.g., gl.xml), enabling dynamic retrieval of function pointers via platform APIs like wglGetProcAddress on Windows, ensuring portability and access to the full API including extensions.[27]

OpenGL Shading Language

The OpenGL Shading Language (GLSL) is a high-level, C-like programming language designed for writing shaders that execute on the graphics processing unit (GPU) within the OpenGL rendering pipeline.[4] Introduced to enable programmable shading, GLSL allows developers to customize vertex processing, fragment coloring, and other stages beyond the fixed-function pipeline of earlier OpenGL versions.[4] Its syntax draws from C, incorporating familiar constructs like functions, loops, and conditionals, while providing GPU-specific features for vector and matrix operations.[4] GLSL versions are closely aligned with OpenGL releases, ensuring compatibility with the API's evolution. For instance, GLSL 1.10 corresponds to OpenGL 2.0, GLSL 1.20 to OpenGL 2.1, GLSL 3.30 to OpenGL 3.3, and GLSL 4.60 to OpenGL 4.6, with each requiring a matching#version directive at the shader's start.[4] Core syntax elements include uniform qualifiers for application-provided constants that remain fixed across shader invocations, varying for data passed from vertex to fragment shaders (deprecated in core profiles since GLSL 1.30 and replaced by in and out), and attribute for per-vertex inputs (also deprecated and superseded by in in vertex shaders).[4] These qualifiers facilitate efficient data flow between the CPU, GPU, and shader stages.

GLSL includes built-in types and functions optimized for graphics computations. Vector types such as vec3 represent three-component single-precision floating-point vectors, while mat4 denotes a 4x4 single-precision floating-point matrix, both essential for transformations and lighting calculations.[4] Built-in functions encompass mathematical operations like dot(vec3, vec3) for computing the dot product of two vectors, and sampling functions such as texture2D(sampler2D, vec2) for accessing 2D textures (deprecated in GLSL 1.30 core in favor of the unified texture function).[4]

Shaders in GLSL are compiled and linked at runtime using OpenGL API calls. The process begins with glCreateShader(GLenum type) to generate a shader object for a specific stage, such as GL_VERTEX_SHADER or GL_FRAGMENT_SHADER. Source code is then loaded via glShaderSource(GLuint shader, GLsizei count, const GLchar *const*string, const GLint *length), followed by glCompileShader(GLuint shader) to translate the GLSL into GPU-executable code, with errors queryable through glGetShaderiv and glGetShaderInfoLog.[36] Compiled shaders are attached to a program object created by glCreateProgram() and linked with glLinkProgram(GLuint program) to form an executable pipeline stage, enabling use via glUseProgram.

A representative vertex shader example demonstrates position transformation:

#version 110

uniform mat4 projection;

uniform mat4 view;

uniform mat4 model;

attribute vec3 position;

void main() {

gl_Position = projection * view * model * vec4(position, 1.0);

}

#version 110

uniform mat4 projection;

uniform mat4 view;

uniform mat4 model;

attribute vec3 position;

void main() {

gl_Position = projection * view * model * vec4(position, 1.0);

}

int and uint with full arithmetic support, enabling advanced computations such as bit operations in shaders.[37]

Version History

Versions 1.0–1.5

OpenGL 1.0, released on June 1, 1992, established the foundational API for 3D graphics rendering, introducing immediate mode operations where vertices and primitives are specified directly in function calls likeglVertex and glBegin/glEnd. This version defined the fixed-function rendering pipeline, which handled transformations, lighting, and rasterization through predefined hardware stages without programmable shaders. Support for double buffering was included to enable smooth animation by swapping front and back buffers via glDrawBuffer and platform-specific context management.[38]

OpenGL 1.1, released on March 4, 1997, enhanced performance and resource management by introducing texture objects, allowing textures to be bound and unbound with glBindTexture for reuse across rendering calls, replacing the less efficient texture naming system of 1.0. Vertex arrays were added to streamline data submission, enabling batched transfers of vertex attributes like positions, normals, and colors through functions such as glVertexPointer and glArrayElement, reducing overhead in immediate mode. These changes improved efficiency for complex scenes without altering the core pipeline.[12]

Released on March 16, 1998, OpenGL 1.2 expanded texture capabilities with support for 3D textures via glTexImage3D, enabling volumetric rendering for effects like medical imaging or cloud simulations. It introduced the BGRA pixel format for better compatibility with Windows systems through glPixelStore parameters, and defined an optional imaging subset that included advanced pixel operations like color matrix transformations and convolution filters, promoted from earlier extensions. These additions leveraged the extension mechanism to integrate hardware-accelerated features incrementally.[39]

OpenGL 1.3, released on August 14, 2001, advanced texturing with multitexturing support, allowing up to 32 texture units to be combined in the fixed pipeline using glActiveTexture and glMultiTexCoord, which facilitated complex material effects like bump mapping. Cube map textures were introduced via glTexImage2D with proxy targets, providing environment mapping for reflections and refractions by sampling six faces of a cube in a single operation. Compressed textures were also added as an optional feature to reduce memory usage.[40]

The OpenGL 1.4 specification, released on July 15, 2002, incorporated automatic mipmap generation with glGenerateMipmap, automating level-of-detail creation for improved texture filtering and performance in distance-based rendering. Depth textures were enabled through GL_DEPTH_COMPONENT internal formats, allowing depth values to be stored and sampled as textures for advanced effects. Shadow mapping hardware support was enhanced with texture comparison modes like GL_COMPARE_R_TO_TEXTURE, enabling efficient shadow calculations in the fixed pipeline.

OpenGL 1.5, released on July 29, 2003, introduced buffer objects, including vertex buffer objects (VBOs) via the promoted ARB_vertex_buffer_object extension, which allowed vertex data to be stored in server-side buffers bound with glBindBuffer for faster access than client-side arrays. This version also supported pixel buffer objects for asynchronous pixel data transfers and further refined shadow mapping with improved depth texture comparisons. Occlusion queries were added using glBeginQuery and glGetQueryObject to count visible pixels, aiding culling in large scenes.[41][42]

OpenGL 2.0

OpenGL 2.0, released on October 22, 2004, introduced a fundamental shift toward programmable graphics processing by integrating the OpenGL Shading Language (GLSL) version 1.10 as a core component of the API.[5][43] This version enabled developers to write custom vertex and fragment shaders, replacing portions of the previously fixed-function rendering pipeline with user-defined code executed on the GPU.[5] The addition of GLSL marked a paradigm change, allowing for greater flexibility in visual effects, lighting, and material properties without relying solely on predefined hardware operations.[43] Central to this programmability were shader objects and program objects, managed through functions likeglCreateShader and glCreateProgram, which allowed compilation, attachment, and linking of shader code into executable programs.[5] Vertex shaders could replace the fixed-function vertex processing stage, handling transformations and per-vertex computations, while fragment shaders enabled customizable per-fragment operations such as texturing and color blending.[5] These features effectively made the rendering pipeline partially programmable, bridging the gap between fixed hardware and software-defined graphics.[5]

OpenGL 2.0 also enhanced rendering efficiency and capabilities with support for multiple render targets (MRTs), facilitated by the glDrawBuffers function, which permitted simultaneous output to several color attachments in a framebuffer.[5] Point sprites were introduced to simplify particle systems and billboarding by allowing texture coordinates to be generated automatically across point primitives, reducing CPU overhead.[5] Additionally, occlusion queries provided a mechanism to count visible fragments efficiently, aiding in early depth testing and culling for performance optimization in complex scenes.[5]

To ensure broad adoption, OpenGL 2.0 maintained full backward compatibility by retaining the fixed-function pipeline alongside the new programmable options, allowing applications to opt into shaders without breaking legacy code.[5] This dual approach preserved existing workflows while encouraging migration to more advanced, customizable rendering techniques.[5]

OpenGL 3.x Series