Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Love wave

View on WikipediaThis article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

In elastodynamics, Love waves, named after Augustus Edward Hough Love, are horizontally polarized surface waves. The Love wave is a result of the interference of many shear waves (S-waves) guided by an elastic layer, which is welded to an elastic half space on one side while bordering a vacuum on the other side. In seismology, Love waves (also known as Q waves (Quer, lit. "lateral" in German)) are surface seismic waves that cause horizontal shifting of the Earth during an earthquake. Augustus Edward Hough Love predicted the existence of Love waves mathematically in 1911. They form a distinct class, different from other types of seismic waves, such as P-waves and S-waves (both body waves), or Rayleigh waves (another type of surface wave). Love waves travel with a lower velocity than P- or S- waves, but faster than Rayleigh waves. These waves are observed only when there is a low velocity layer overlying a high velocity layer/sub–layers.

Description

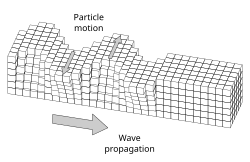

[edit]The particle motion of a Love wave forms a horizontal line, perpendicular to the direction of propagation (i.e. are transverse waves). Moving deeper into the material, motion can decrease to a "node" and then alternately increase and decrease as one examines deeper layers of particles. The amplitude, or maximum particle motion, often decreases rapidly with depth.

Since Love waves travel on the Earth's surface, the strength (or amplitude) of the waves decrease exponentially with the depth of an earthquake. However, given their confinement to the surface, their amplitude decays only as , where represents the distance the wave has travelled from the earthquake. Surface waves therefore decay more slowly with distance than do body waves, which travel in three dimensions. Large earthquakes may generate Love waves that travel around the Earth several times before dissipating.

Since they decay so slowly, Love waves are the most destructive outside the immediate area of the focus or epicentre of an earthquake. They are what most people feel directly during an earthquake.

In the past, it was often thought that animals like cats and dogs could predict an earthquake before it happened. However, they are simply more sensitive to ground vibrations than humans and are able to detect the subtler body waves that precede Love waves, like the P-waves and the S-waves.[1]

Basic theory

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2020) |

The conservation of linear momentum of a linear elastic material can be written as:[2]

where is the displacement vector and is the stiffness tensor. Love waves are a special solution () that satisfy this system of equations. We typically use a Cartesian coordinate system () to describe Love waves.

Consider an isotropic linear elastic medium in which the elastic properties are functions of only the coordinate, i.e., the Lamé parameters and the mass density can be expressed as . Displacements produced by Love waves as a function of time () have the form

These are therefore antiplane shear waves perpendicular to the plane. The function can be expressed as the superposition of harmonic waves with varying wave numbers () and frequencies (). Consider a single harmonic wave, i.e.,

where is the imaginary unit, i.e. . The stresses caused by these displacements are

If we substitute the assumed displacements into the equations for the conservation of momentum, we get a simplified equation

The boundary conditions for a Love wave are that the surface tractions at the free surface must be zero. Another requirement is that the stress component in a layer medium must be continuous at the interfaces of the layers. To convert the second order differential equation in into two first order equations, we express this stress component in the form

to get the first order conservation of momentum equations

The above equations describe an eigenvalue problem whose solution eigenfunctions can be found by a number of numerical methods. Another common, and powerful, approach is the propagator matrix method (also called the matricant approach).[citation needed]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- A. E. H. Love, "Some problems of geodynamics", first published in 1911 by the Cambridge University Press and published again in 1967 by Dover, New York, USA. (Chapter 11: Theory of the propagation of seismic waves)

- ^ "What Is Seismology?". Michigan Technological University. 2007. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ^ The body force is assumed to be zero and direct tensor notation has been used. For other ways of writing these governing equations see linear elasticity.

Love wave

View on GrokipediaIntroduction

Definition

Love waves are horizontally polarized shear waves, also known as SH waves, that propagate along the Earth's surface in a transverse manner.[5] They are named after the British mathematician Augustus Edward Hough Love, who theoretically predicted their existence.[6] The defining characteristic of Love waves is their transverse particle motion, which occurs parallel to the surface and perpendicular to the direction of propagation, producing horizontal shearing of the ground.[2][7] Unlike vertical motions seen in other phenomena, this shearing lacks any vertical component, causing the ground to shift side-to-side in a linear fashion.[5] These waves form as surface waves generated by earthquakes or explosions, traveling through the upper crustal layers via interactions with the Earth's free surface and shallow structures.[2][7] They propagate more slowly than body waves, with typical velocities ranging from 2 to 6 km/s depending on the period and medium, but can exceed the speeds of certain other surface waves in specific geological settings.[2] A clear visualization of Love wave motion involves imagining the ground sliding horizontally back and forth, akin to shaking a tablecloth sideways without lifting it, which highlights their purely horizontal displacement.[7][2]Historical Discovery

Augustus Edward Hough Love, a British mathematician, laid the theoretical foundation for Love waves through his extensive work on the theory of elasticity and seismology spanning from 1892 to 1911. His seminal 1892 publication, A Treatise on the Mathematical Theory of Elasticity, provided the elastic framework essential for modeling wave propagation in solids, while subsequent papers explored geophysical applications, culminating in his prediction of horizontally polarized surface waves. In 1911, Love explicitly predicted the existence of these waves—now known as Love waves—in his Adams Prize-winning essay Some Problems of Geodynamics, where he derived solutions for shear waves guided along the interface between elastic layers with differing shear velocities, demonstrating their dispersive propagation in such media. These equations represented a key advancement in understanding surface waves in elastic media, predating widespread direct seismic recordings of such phenomena.[8] The first observational confirmation of Love waves came in the early 1920s through the analysis of seismograms by German-American seismologist Beno Gutenberg. In the early 1920s, through analysis of seismograms from major earthquakes, including the February 3, 1923, Kamchatka earthquake (M 8.4), Gutenberg identified dispersive transverse surface waves in his 1924 publications, marking the initial empirical evidence for Love's theoretical predictions and proposing their use to infer crustal thickness and elastic properties.[9][10] Gutenberg's analysis involved measuring dispersion in transverse surface waves on global seismograms to infer crustal properties. Although Love's original model assumed purely horizontal shear (SH) polarization, subsequent refinements in the 1920s and 1930s, building on Gutenberg's observations and further seismogram analyses, confirmed the absence of vertical motion and the SH nature of these waves.[9] Love's equations, formulated before routine teleseismic observations, remarkably aligned with later long-distance seismic data, validating their predictive power and influencing the evolution of seismological theory. This alignment facilitated the integration of theoretical models with empirical evidence, solidifying Love waves' role in probing Earth's interior structure.[8]Physical Characteristics

Particle Motion and Polarization

Love waves exhibit particle motion consisting of horizontal displacements perpendicular to the direction of propagation, with no vertical component, resulting in a purely transverse shear oscillation.[5] This motion is analogous to that of body SH waves but trapped near the surface, where particles move in linear paths parallel to the Earth's surface, typically within the uppermost crustal layers.[11] The polarization of Love waves is strictly shear horizontal (SH), comprising only horizontal shear components without any shear vertical (SV) or compressional (P) wave influences at the free surface.[12] This SH polarization arises from the constructive interference of multiple SH reflections within a low-velocity surface layer overlying a higher-velocity substrate, as originally derived by Love in his analysis of geodynamic problems.[13] In a stratified Earth model, the horizontal particle displacement decays exponentially with increasing depth below the surface, achieving maximum amplitude at the free boundary and diminishing rapidly in the underlying half-space.[11] This depth-dependent attenuation confines the wave's energy to shallow depths, typically on the order of the layer thickness, enhancing its sensitivity to near-surface geology.[14] For instance, in areas underlain by soft, unconsolidated sediments, Love waves generate intensified horizontal ground shaking during earthquakes, which can exacerbate structural damage to buildings and infrastructure due to the prolonged transverse motions.[15] Unlike certain other surface waves, the SH polarization of Love waves remains constant and independent of frequency, maintaining its transverse horizontal orientation across the seismic spectrum.[14]Propagation Speed and Attenuation

Love waves propagate through the Earth's crust at typical velocities ranging from 2.0 to 4.5 km/s, influenced by the frequency of the wave and the properties of the medium.[16] These speeds are slower in sedimentary layers, where velocities often fall between 1 and 2 km/s due to lower shear wave velocities in unconsolidated materials.[17] The propagation velocity of Love waves fundamentally depends on the shear modulus, which measures the material's resistance to shear deformation, and the density of the rock or sediment, as these parameters determine the underlying shear wave speed in the guiding layer.[2] Attenuation of Love waves occurs primarily through viscoelastic damping, where internal friction in the Earth materials converts wave energy into heat, and scattering caused by heterogeneities in the subsurface structure.[18][19] This energy loss is more pronounced in heterogeneous media, such as regions with variable rock types or faults, leading to greater dissipation compared to more uniform paths. The quality factor (Q), which quantifies the efficiency of energy retention, typically ranges from 50 to 200 for Love waves in the upper crust, with lower values indicating higher attenuation at shorter periods.[20][21] Love waves are guided along surface layers where the shear velocity increases with depth, confining their energy near the surface and making them particularly sensitive to variations in crustal thickness.[14] In a homogeneous half-space, Love waves do not exist, but in layered media like the Earth's crust, they exhibit dispersion, resulting in frequency-dependent propagation speeds.[22] For instance, in global earthquakes, low-frequency components of Love waves experience longer travel times due to their slower velocities in deeper, more dispersive crustal structures.[2]Mathematical Theory

Derivation from Wave Equations

The derivation of Love waves originates from the equations governing wave propagation in elastic media, as developed in the theory of linear isotropic elasticity. The starting point is Navier's equation, which describes the motion of the displacement vector in the absence of body forces: where is the density, and are the Lamé parameters, and the equation balances inertial forces with elastic stresses.[23][24] For Love waves, which are transversely polarized surface waves, the analysis assumes shear-horizontal (SH) motion decoupled from compressional and shear-vertical components. This requires a two-dimensional propagation geometry in the - plane (with increasing downward), where the displacement is purely horizontal and perpendicular to the direction of propagation: , with no variation in the -direction. Under these conditions, the dilatation , and the curl terms simplify, reducing Navier's equation to the scalar wave equation for the SH component: or equivalently, where is the shear-wave speed and . This form highlights the transverse shear nature of the motion, suitable for vertically heterogeneous media where properties vary with depth .[23][24] To derive plane-wave solutions, introduce a scalar potential such that , representing the SH displacement field. For harmonic time dependence and propagation along , assume a separable form , where is the horizontal wavenumber and is the angular frequency. Substituting into the wave equation yields the one-dimensional ordinary differential equation for the depth-dependent amplitude: This is the Helmholtz equation in the vertical direction, often written as in the full spatial domain, where is the squared wavenumber for shear waves (with ). The separation of variables isolates the horizontal plane-wave propagation from the vertical structure, enabling solutions that decay or oscillate with depth depending on whether (propagating) or (evanescent), which is essential for surface-trapped modes in layered media.[23][24]Boundary Conditions and Solutions

To derive the explicit solutions for Love wave propagation, boundary conditions are applied to the general SH wave equation, which governs the horizontal displacement in a transversely polarized shear wave. At the free surface of the Earth, located at , the condition of zero shear stress must hold, expressed as , where is the shear modulus. This traction-free boundary ensures that no external forces act on the surface, leading to a specific form of the displacement field that satisfies the condition through cosine terms.[25] In a layered medium, such as a crustal layer overlying a half-space, continuity conditions are enforced at each interface . These require both the displacement and the shear stress to be continuous across the boundary, preventing discontinuities in the wave field that would imply unphysical breaks in the material. For a simple two-layer model with a surface layer of thickness and shear velocity , and an underlying half-space with , the displacement in the layer (0 \leq z \leq H) takes the form , where is the vertical wavenumber in the layer (real for phase velocity satisfying ). In the half-space (z \geq H), the solution is evanescent: , with , ensuring decay into the substrate without radiation.[25][11] Applying the boundary and continuity conditions yields the explicit solution through a dispersion relation, which matches the wavenumbers across layers and results in a transcendental equation. For the two-layer case, this is given by where and are the shear moduli of the layer and half-space, respectively. This equation determines the allowed phase velocities for which non-trivial solutions exist, producing discrete modes (fundamental and overtones) that depend on frequency, layer properties, and thickness. Love waves, being SH waves by construction, exhibit only horizontal transverse displacement with no vertical component, and in symmetric setups, only even modes are supported due to the reflection characteristics at the free surface.[25]Dispersion Relations

Frequency-Dependent Behavior

Love waves exhibit frequency-dependent behavior primarily due to the Earth's heterogeneous structure, particularly in models consisting of low-velocity sedimentary layers overlying higher-velocity bedrock. In a uniform elastic half-space, Love waves do not exist, and propagating SH waves are non-dispersive, traveling at a constant shear velocity independent of frequency. However, in layered media such as the crust, Love waves become dispersive, with their phase velocity varying as a function of angular frequency . Typically, in structures where shear velocity increases with depth, the phase velocity decreases with increasing frequency: at high frequencies, waves are sensitive to shallower, slower layers, resulting in lower velocities, while at low frequencies, they sense deeper, faster material, leading to higher velocities.[12] The underlying mechanism for this dispersion arises from the depth-dependent penetration of wave energy in stratified media. Higher-frequency components, characterized by shorter wavelengths, are largely confined to the near-surface layers where shear velocities are lower, causing their propagation to be governed primarily by these slower materials. In contrast, lower-frequency components have longer wavelengths and penetrate deeper into the structure, interacting with underlying layers of higher shear velocity, such as bedrock, which effectively increases their overall propagation speed. This differential confinement leads to the observed variation in phase velocity and is a direct consequence of the boundary conditions at layer interfaces that trap the wave energy near the surface while allowing partial leakage to depth for longer periods.[12][11] Love wave dispersion is further characterized by the existence of multiple modes, each with distinct frequency ranges. The fundamental mode (n=0) can propagate at all frequencies above zero, providing a baseline dispersive curve that spans the full spectrum relevant to seismic observations. Higher-order modes (n=1, 2, ...), however, are subject to cutoff frequencies below which they cannot propagate; these cutoffs occur when the wavelength becomes too long relative to the layer thickness, preventing constructive interference for that mode. Above their respective cutoffs, higher modes contribute additional branches to the dispersion relation, often exhibiting more pronounced frequency dependence in complex crustal models.[12] In practice, this frequency-dependent behavior manifests in seismograms from regional earthquakes, where Love wave arrivals display dispersion through varying arrival times across the frequency band. Higher-frequency components arrive earlier due to their slower phase velocities in shallow layers, while lower-frequency components lag, resulting in a broadening or stretching of the wave train over distance. This effect is evident in transverse-component records, aiding in the identification and analysis of crustal structure.[26]Group and Phase Velocities

In the theory of Love waves, the phase velocity is defined as , where is the angular frequency and is the horizontal wavenumber; this quantity represents the propagation speed of constant-phase planes along the Earth's surface.[27] Due to the layered structure of the Earth, Love waves exhibit dispersion, with decreasing as a function of .[11] The group velocity , given by , describes the speed at which the overall wave packet or energy propagates through the medium.[28] In dispersive media such as the Earth's crust and mantle, is typically less than , reflecting the separation between the motion of individual wave crests and the envelope of the wave train.[12] For Love waves propagating in typical Earth models, such as those with a crustal layer over a half-space mantle, the group velocity satisfies at low frequencies, where longer-period waves sense deeper, faster shear velocities; the dispersion curves cross at higher frequencies as shorter waves are confined to shallower, slower layers. The relationship between these velocities, derived from the dispersion curve, is expressed as which highlights how changes in phase velocity with frequency influence energy transport.[29] In multimodal dispersion curves for Love waves, the Airy phase appears at the frequency where the group velocity is stationary (), resulting in maximum amplitude from constructive interference among modes and marking a stationary point in group velocity.[30] This feature is prominent in seismograms and aids in interpreting crustal structure.Applications and Significance

Role in Seismology

Love waves play a crucial role in seismology, particularly in the detection and characterization of earthquakes. Due to their transverse horizontal polarization, they are prominently recorded on horizontal-component seismometers, where they appear as strong shear motions perpendicular to the propagation direction.[31] This distinct signature allows seismologists to identify their arrival following body waves, and their travel-time curves, which account for dispersion, enable estimation of epicentral distances, especially at regional to teleseismic ranges beyond 1000 km.[32] In earthquake location procedures, Love wave arrivals complement body wave data, providing robust constraints for events where surface waves are well-developed.[33] In magnitude estimation, Love waves contribute significantly to the surface-wave magnitude , which measures the amplitude of surface waves at periods around 20 seconds.[34] Their inclusion refines calculations.[35] Techniques like the method apply to Love waves by measuring peak velocities on transverse components, yielding magnitudes comparable to those from Rayleigh waves with standard deviations of about 0.22 magnitude units.[34] Love waves pose substantial hazards during earthquakes by generating intense horizontal ground motions that persist over long distances, amplifying damage to structures.[36] Their shear oscillations cause excessive lateral swaying and structural failure, as the horizontal forces exceed design limits for shear walls and frames.[37] This motion is particularly destructive in urban settings, where it can topple unreinforced masonry or overload moment-resisting frames.[37] Analyses from the 1960s, enabled by global seismic networks like the World-Wide Standardized Seismograph Network (WWSSN), revealed that Love waves dominate propagation along continental paths due to the thick, low-velocity crustal layers that guide them efficiently.[38] In contrast, oceanic paths exhibit weaker Love wave amplitudes owing to the thin sedimentary layer over high-velocity oceanic crust, which limits mode excitation and increases attenuation.[39] For instance, during the 2011 Tohoku earthquake (), Love waves were amplified by factors exceeding 10 in the sedimentary basins of the Kanto and Osaka regions, prolonging ground motions and contributing to widespread infrastructure damage over 300 km from the epicenter.[40][41] This event underscored how basin-edge effects trap and enhance Love wave energy, informing modern seismic hazard models.[41]Geophysical Exploration

In geophysical exploration, Love waves are employed in active-source methods, particularly the multichannel analysis of surface waves (MASW) adapted for Love waves (MASLW), to image shallow subsurface structures. These methods utilize controlled sources such as vibroseis trucks generating horizontal shear motion or impact sources like hammers with horizontal traction planks to excite Love waves, which are recorded using linear arrays of horizontal-component geophones. This approach leverages the transverse horizontal polarization of Love waves to isolate them from other wave types, enabling effective noise suppression through trace-to-trace coherency analysis in arrival time and amplitude.[42][43] The acquired data yield dispersion curves, which are inverted to obtain shear-wave velocity (Vs) profiles that delineate subsurface layering, including depth to bedrock. Inversion typically involves iterative forward modeling of the observed phase velocities against theoretical curves for layered media, often using software like Dinver to estimate Vs and layer thicknesses down to depths of 30–60 m. Love wave dispersion properties, characterized by frequency-dependent phase velocities, provide robust constraints for these inversions, particularly in revealing velocity contrasts associated with soil-bedrock interfaces.[42][44] Applications of Love wave MASW include site characterization for civil engineering projects, where Vs profiles assess soil stiffness and liquefaction potential; groundwater mapping by imaging buried valleys and aquifers through velocity variations in overburden sediments; and hydrocarbon detection via near-surface velocity models that correct deeper seismic reflections for statics in oil and gas exploration. These techniques gained prominence in the 1980s–1990s, coinciding with the advent of digital seismographs that facilitated multichannel recording and computational inversion. Love waves are often preferred over Rayleigh waves in such surveys due to their purely horizontal transverse polarization, which simplifies mode identification and reduces interference from higher modes.[42][44][45] For example, in urban site investigations at the University of Pretoria Hillcrest Campus, Love wave MASW revealed soft soil layers up to 30 m deep overlying bedrock, informing geotechnical assessments for infrastructure development. Similarly, surveys in southern Ontario imaged a buried valley with overburden thicknesses exceeding 30 m, correlating velocity lows with aquifer zones validated by water well data.[42][44]Comparisons with Other Waves

Versus Rayleigh Waves

Love waves exhibit purely horizontal transverse polarization, with particle motion confined to the SH (shear horizontal) direction perpendicular to the direction of propagation, whereas Rayleigh waves display elliptical retrograde motion in the vertical plane, combining vertical and radial (P-SV) components.[12][11] This distinction arises because Love waves derive from trapped SH waves in layered media, while Rayleigh waves result from the interference of P and SV waves at a free surface.[33] In terms of generation, Love waves are more readily excited by transverse shear sources, such as strike-slip earthquakes that produce strong SH radiation, whereas Rayleigh waves are preferentially generated by compressional or vertical sources, like thrust faults, due to their coupling of P and SV motions.[46][11] Love waves are less sensitive to variations in Poisson's ratio and primarily probe the shear wave structure of the subsurface, offering advantages in isolating S-wave velocity profiles without interference from compressional effects; in contrast, Rayleigh waves couple P and SV components, making them more responsive to Poisson's ratio and broader elastic properties.[47][12] A key theoretical difference is that Love waves cannot exist in a fluid half-space, as they require a shear modulus and velocity layering to form, while Rayleigh waves can propagate in a homogeneous elastic half-space at any free surface, though both are absent in purely fluid media lacking shear support.[33] Their phase velocities are similar overall, but Love waves typically travel faster than Rayleigh waves in crustal structures due to their transverse nature and sensitivity to shear layering.[11] On seismograms, this orthogonality allows clear separation: Love waves dominate the transverse component with horizontal arrivals, while Rayleigh waves appear on vertical and radial components with elliptical signatures, facilitating independent analysis in teleseismic records.[12][11]Versus Body Waves

Love waves, as surface waves, propagate along the Earth's surface with their energy confined to shallow depths, exhibiting evanescent decay where amplitude decreases exponentially with depth below the surface, in contrast to body waves that traverse the full volume of the Earth's interior. Primary (P) waves, which are compressional, and secondary (S) waves, which are shear, travel through the solid and liquid portions of the planet (P waves through all media, S waves only through solids), allowing them to probe deep structures inaccessible to surface-guided waves. This volumetric propagation enables body waves to provide information on the Earth's core and mantle, while Love waves are limited to crustal and uppermost mantle features due to their guided, horizontally polarized motion perpendicular to the direction of travel.[48][2][7] In terms of speed, body waves outpace Love waves, with typical crustal velocities for P waves ranging from 5 to 8 km/s and for S waves from 3 to 4.5 km/s, compared to Love wave speeds of approximately 2 to 4 km/s, which are dispersive and vary with frequency. This velocity difference arises from the unconstrained three-dimensional (3D) radiation of body waves versus the two-dimensional (2D) guidance of Love waves along the surface. Energy distribution further distinguishes them: body waves radiate spherically in 3D, leading to faster amplitude decay with distance (proportional to 1/r, with energy decay proportional to 1/r²) and typically higher frequencies that attenuate more quickly, whereas Love waves concentrate energy near the surface in a 2D pattern (amplitude decay proportional to 1/√r, with energy decay proportional to 1/r), supporting lower frequencies and longer-duration wave trains that persist over greater distances.[49][50][51][16] On seismograms, Love waves arrive after S waves but generally before or concurrently with Rayleigh waves, forming part of the surface wave train that follows the initial body wave arrivals, which is particularly evident in records from distant (teleseismic) earthquakes where P and S waves appear first as sharp impulses, succeeded by the prolonged, lower-amplitude oscillations of the surface wave train. This sequence allows seismologists to distinguish crustal properties via Love waves, which body waves largely bypass due to their deeper penetration paths. For instance, in teleseismic events, the early body wave phases reveal bulk Earth structure, while the subsequent Love wave components highlight near-surface layering and heterogeneity.[2][7][52]References

- https://wiki.seg.org/wiki/Dictionary:Love_wave

![{\displaystyle {\hat {v}}(x,z,t)=V(k,z,\omega )\,\exp[i(kx-\omega t)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4934aabe0934acf9fe5952e8b6a6d54c676bcc7b)

![{\displaystyle \sigma _{xx}=0~,~~\sigma _{yy}=0~,~~\sigma _{zz}=0~,~~\tau _{zx}=0~,~~\tau _{yz}=\mu (z)\,{\frac {dV}{dz}}\,\exp[i(kx-\omega t)]~,~~\tau _{xy}=ik\mu (z)V(k,z,\omega )\,\exp[i(kx-\omega t)]\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2992bba4ff7eb58d9994ebb822048c59c69ec9d3)

![{\displaystyle {\frac {d}{dz}}\left[\mu (z)\,{\frac {dV}{dz}}\right]=[k^{2}\,\mu (z)-\omega ^{2}\,\rho (z)]\,V(k,z,\omega )\,.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c1d27f29793193d2104148cd44eae8c82c890fd2)

![{\displaystyle \tau _{yz}=T(k,z,\omega )\,\exp[i(kx-\omega t)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3fd9af4878c2a3419cfebd8f32ced2e4b394799c)