Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Lu (state)

View on Wikipedia

Key Information

| Lu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Lu" in seal script (top), traditional (middle), and simplified (bottom) characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 魯 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 鲁 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lu (Chinese: 魯; c. 1042 – 249 BC) was a vassal state during the Zhou dynasty of ancient China located around modern southwest Shandong. Founded in the 11th century BC, its rulers were from a cadet branch of the House of Ji (姬) that ruled the Zhou dynasty. The first duke was Boqin, a son of the Duke of Zhou, who was brother of King Wu of Zhou and regent to King Cheng of Zhou.[1]

Lu was the home state of Confucius as well as Mozi, and, as such, has an outsized cultural influence among the states of the Eastern Zhou and in history. The Annals of Spring and Autumn, for instance, was written with the Lu rulers' years as their basis. Another great work of Chinese history, the Zuo Zhuan or Commentary of Zuo, was traditionally considered to have been written in Lu by Zuo Qiuming.

Geography

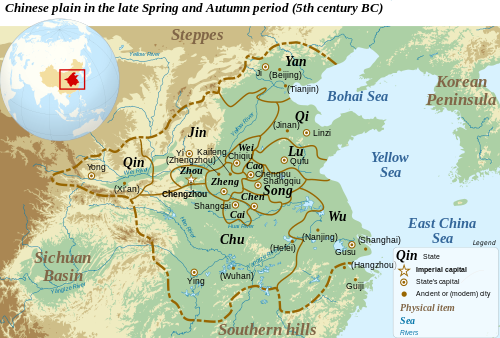

[edit]The state's capital was in Qufu and its territory mainly covered the central and southwest regions of what is now Shandong Province. It was bordered to the north by the powerful state of Qi and to the south by the powerful state of Chu. The position of Lu on the eastern frontiers of the Western Zhou state, facing the non-Zhou peoples in states such as Lai and Xu, was an important consideration in its foundation.

Etymology

[edit]William H. Baxter (apud Matisoff, 1995) suggests a semantic connection between the toponym 魯 Lǔ and its homophone 鹵 lǔ "salty, rock salt" (< OC *C-rāʔ) since that region was a salt marsh in ancient times.[2]

History

[edit]Lu was one of several states founded in eastern China at the very beginning of the Zhou dynasty, in order to extend Zhou rule far from its capital at Zongzhou and power base in the Guanzhong region. Throughout Western Zhou times, it played an important role in stabilising Zhou control in modern-day Shandong.

During the early Spring and Autumn period, Lu was one of the strongest states and a rival of Qi to its north. Under Duke Yin and Duke Huan of Lu, Lu defeated both Qi and Song on several occasions. At the same time, it undertook expeditions against other minor states.

This changed by the middle of the period, as Lu's main rival, Qi, grew increasingly dominant. Although a Qi invasion was defeated in the Battle of Changshao in 684 BC, Lu would never regain the upper hand against its neighbour. Meanwhile, the power of the dukes of Lu was eventually undermined by the powerful feudal clans of Jisun (季孫), Mengsun (孟孫), and Shusun 叔孫 (called the Three Huan because they were descendants of Duke Huan of Lu). The domination of the Three Huan was such that Duke Zhao of Lu, in attempting to regain power, was exiled by them and never returned. It would not be until Duke Mu of Lu's reign, in the early Warring States period, that power eventually returned to the dukes again.

In 249 BC King Kaolie of the state of Chu invaded and annexed Lu. Duke Qing, the last ruler of Lu, became a commoner.[1][3]

The main line of the Duke of Zhou's descendants came from his firstborn son, the State of Lu ruler Bo Qin's third son Yu (魚) whose descendants adopted the surname Dongye (東野). The Duke of Zhou's offspring held the title of Wujing Boshi (五经博士; 五經博士; Wǔjīng Bóshì).[4][5]

Mencius was a descendent of Qingfu (慶父), one of Duke Huan of Lu's sons. The genealogy is found in the Mencius family tree (孟子世家大宗世系).[6][7][8]

Rulers

[edit]

List of Lu rulers based on the Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian:[1][3]

| Title | Given name | Reign | Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duke Tai | Boqin | c. 1042–997 BC | son of Duke of Zhou |

| Duke Kao | You | 998–995 BC | son of Boqin |

| Duke Yang | Xi or Yi | 994–989 BC | brother of Duke Kao |

| Duke You | Zai or Yu | 988–975 BC | son of Duke Yang |

| Duke Wei | Fei | 974–925 BC | brother of Duke You |

| Duke Li | Zhuo or Di | 924–888 BC | son of Duke Wei |

| Duke Xian | Ju | 887–856 BC | brother of Duke Li |

| Duke Shen | Bi or Zhi | 855–826 BC | son of Duke Xian |

| Duke Wu | Ao | 825–816 BC | brother of Duke Shen |

| Duke Yi | Xi | 815–807 BC | son of Duke Wu |

| none | Boyu | 806–796 BC | nephew of Duke Yi |

| Duke Xiao | Cheng | 795–769 BC | brother of Duke Yi |

| Duke Hui | Fuhuang or Fusheng | 768–723 BC | son of Duke Xiao |

| Duke Yin | Xigu | 722–712 BC | son of Duke Hui |

| Duke Huan | Yun or Gui | 711–694 BC | brother of Duke Yin |

| Duke Zhuang | Tong | 693–662 BC | son of Duke Huan |

| Ziban | Ban | 662 BC | son of Duke Zhuang |

| Duke Min | Qi | 661–660 BC | son of Duke Zhuang |

| Duke Xi | Shen | 659–627 BC | son of Duke Zhuang |

| Duke Wen I | 626–609 BC | son of Duke Xi | |

| Duke Xuan | Tui or Wo | 608–591 BC | son of Duke Wen I |

| Duke Cheng | Heigong | 590–573 BC | son of Duke Xuan |

| Duke Xiang | Wu | 572–542 BC | son of Duke Cheng |

| Ziye | Ye | 542 BC | son of Duke Xiang |

| Duke Zhao | Chou | 541–510 BC | son of Duke Xiang |

| Duke Ding | Song | 509–495 BC | brother of Duke Zhao |

| Duke Ai | Jiang | 494–467 BC | son of Duke Ding |

| Duke Dao | Ning | 466–429 BC | son of Duke Ai |

| Duke Yuan | Jia | 428–408 BC | son of Duke Dao |

| Duke Mu | Xian | 407–377 BC | son of Duke Yuan |

| Duke Gong | Fen | 376–353 BC | son of Duke Mu |

| Duke Kang | Tun | 352–344 BC | son of Duke Gong |

| Duke Jing | Yan | 343–323 BC | son of Duke Kang |

| Duke Ping | Shu | 322–303 BC | son of Duke Jing |

| Duke Wen II | Jia | 302–278 BC | son of Duke Ping |

| Duke Qing | Chou | 277–249 BC | son of Duke Wen II |

Rulers family tree

[edit]| Lu state | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Sima Qian. 鲁周公世家 [House of Duke of Zhou of Lu]. Records of the Grand Historian (in Chinese). Retrieved 15 April 2012.

- ^ Matisoff, James A. (1995). “Sino-Tibetan Palatal Suffixes Revisited”. In: Nishi, Y., Matisoff, J. A. and Nagano, Y. (editors), Senri Ethnological Studies. 41: p. 52, n. 40 of 35–91.

- ^ a b Han, Zhaoqi (2010). "House of Duke of Zhou of Lu". Annotated Shiji (in Chinese). Zhonghua Book Company. p. 2691. ISBN 978-7-101-07272-3.

- ^ H.S. Brunnert; V.V. Hagelstrom (2013). Present Day Political Organization of China. Routledge. pp. 493–494. ISBN 978-1-135-79795-9.

- ^ 王士禎 (3 September 2014). 池北偶談. 朔雪寒. GGKEY:ESB6TEXXDCT.

- ^ 《三遷志》,(清)孟衍泰續修

- ^ 《孟子世家譜》,(清)孟廣均主編,1824年

- ^ 《孟子與孟氏家族》,孟祥居編,2005年

External links

[edit] Media related to Lu (state) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lu (state) at Wikimedia Commons- Qin ding da Qing hui dian (Jiaqing chao)0. 1818. p. 1084.

- 不詳 (21 August 2015). 新清史. 朔雪寒. GGKEY:ZFQWEX019E4.

- "曝書亭集 : 卷三十三 – 中國哲學書電子化計劃". ctext.org. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- "什么是 五经博士 意思详解 – 淘大白". www.taodabai.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- 王士禎 (3 September 2014). 池北偶談. 朔雪寒. GGKEY:ESB6TEXXDCT.

- 徐錫麟; 錢泳 (10 September 2014). 熙朝新語. 朔雪寒. GGKEY:J62ZFNAA1NF.

- "【从世袭翰林院五经博士到奉祀官】_三民儒家_新浪博客". blog.sina.com.cn. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

Lu (state)

View on GrokipediaGeography

Location and Physical Features

The state of Lu was located in the southwestern portion of present-day Shandong Province, eastern China, at the eastern edge of the Yellow River Plain.[2][1] Its territory primarily encompassed fertile lowlands suitable for agriculture, with the Yellow River flowing to the north influencing sedimentation and soil fertility.[3][1] The physical geography featured alluvial plains interspersed with gentle hills and the foothills of Mount Tai (Taishan), situated near the capital at Qufu.[1][3] This terrain, part of the broader North China Plain, supported intensive dry-land farming of crops such as millet, bolstered by a warm temperate monsoon climate that provided adequate rainfall and seasonal flooding for irrigation.[3] The absence of major rugged barriers within Lu's borders contributed to its relative agricultural stability during the Zhou dynasty.[1]Capital and Administrative Centers

The capital of the state of Lu was Qufu, situated in present-day southwestern Shandong Province.[1] Established during the early Western Zhou dynasty circa the 11th century BC, Qufu functioned as the primary political and administrative hub for over 800 years, from the state's founding until its conquest by the state of Chu in 249 BC.[4] Archaeological excavations reveal that the city featured extensive fortifications, including rammed-earth walls enclosing palaces and ritual structures, indicative of its role as a centralized seat of ducal authority.[5] While Qufu dominated as the core administrative center, the state's governance increasingly involved influential noble clans, particularly the Three Huan families (Ji, Meng, and Shu), who controlled key territories and military resources from bases within or near the capital during the Spring and Autumn period.[1] No distinct secondary capitals are documented, though walled settlements such as those in surrounding counties served local administrative functions under ducal oversight.[6] This structure reflected Lu's feudal organization, where power radiated from Qufu amid internal clan rivalries that undermined central control by the late period.[1]Name and Etymology

Origins of the Name "Lu"

The name "Lu" (Chinese: 魯; pinyin: Lǔ) designates the vassal state enfeoffed to Boqin (伯禽), eldest son of the Duke of Zhou (周公), by King Cheng of Zhou (周成王) circa 1042 BCE, following the conquest of the Shang remnant state of Yan (奄) in the region around modern Qufu, Shandong Province.[1] This territory, on the eastern fringes of the Zhou cultural sphere, retained or adopted the pre-existing local appellation "Lu," likely reflecting indigenous nomenclature from the Dongyi (東夷) peoples who inhabited the area and were mythologically linked to the ancient emperor Shao Hao (少昊), whose traditional residence was placed at Qufu.[1] The Chinese character 魯 is a phono-semantic compound (形聲字), comprising the semantic radical for "fish" (魚) above a phonetic component derived from 甘 ("sweet" or "mouth"), suggesting an original pictographic connotation of a "tasty fish" or gustatory quality, possibly alluding to local aquatic resources or environmental features in the state's riverine plains. Over time, as a phonetic loan, 魯 extended to meanings like "blunt," "rude," or "extreme" (as explained in the Eastern Han dictionary Shuowen Jiezi [說文解字], circa 100 CE: "魚甘聲。魯,甚也"—"voiced with fish and sweetness; Lu means 'intense'"), but its application to the state name predates these semantic shifts and appears primarily toponymic rather than descriptive.[7] No surviving Zhou-era texts, such as the Shiji (史記) of Sima Qian (circa 100 BCE), provide an explicit mythological or linguistic derivation for "Lu" beyond its association with the enfeoffment charter (Lüshi Chunqiu references notwithstanding, which focus on governance rather than nomenclature).[8] The persistence of the name into later periods, including as a surname for descendants of Lu nobility and a shorthand for Shandong, underscores its rootedness in the Zhou reconfiguration of eastern territories to consolidate control over non-Huaxia groups.[1]Historical Development

Establishment During Western Zhou

The state of Lu was established in the early Western Zhou period (c. 1046–771 BCE) through the enfeoffment of territory in the eastern regions to consolidate Zhou control following the conquest of the Shang dynasty. The territory, centered around what is now Qufu in Shandong province, was initially appointed to Ji Dan, the Duke of Zhou and brother of the dynasty's founder King Wu, as part of the Zhou feudal system designed to administer distant lands via royal kin. However, due to the Duke of Zhou's role as regent for the young King Cheng after King Wu's death, he delegated the governance of Lu to his eldest son, Boqin (姬伯禽), who became the state's first duke.[1] This enfeoffment occurred amid the Duke of Zhou's eastern expeditions to suppress rebellions by Shang remnants and local groups, ensuring loyalty in the Shandong area, historically linked to ancient polities like that of the legendary Shao Hao. Bronze inscriptions from the early Western Zhou corroborate the pattern of such grants to Zhou nobility, with Lu serving as a military and administrative outpost to oversee eastern frontiers and perform rites tied to Zhou ancestral worship. Boqin's installation marked Lu's transformation from a frontier zone into a structured vassal state, emphasizing Zhou ideals of ritual propriety and hierarchical order.[9][1] The precise date of Boqin's enfeoffment aligns with the inception of Western Zhou rule around 1046 BCE, though specific records derive from later historical compilations reflecting traditional accounts rather than direct contemporary epigraphy for the event itself. Lu's founding underscored the Zhou strategy of decentralizing authority to kin while maintaining central oversight, fostering stability in a region prone to unrest from non-Zhou peoples.[1]Events in the Spring and Autumn Period

The Spring and Autumn Period in Lu began with the accession of Duke Yin in 723 BC, marking the start of the state's official chronicle, the Spring and Autumn Annals, which recorded major court events, accessions, deaths, battles, and diplomatic activities over 242 years until 481 BC.[1] Early reigns were marked by instability and assassinations; Duke Huan (r. 712–694 BC) was killed by forces of Qi due to an illicit affair involving his wife, while Duke Min (r. 662–660 BC) was assassinated amid a power struggle with the minister Qing Fu over the duchess.[1] These events reflected Lu's vulnerability to internal plots and external interference from neighboring states like Qi, which frequently meddled in Lu's succession and territory.[1] A defining development was the rise of the Three Huan families—Jisun, Mengsun, and Shusun—descended from sons of Duke Huan of Lu, who were enfeoffed as ministers and gradually amassed power during the reigns of Dukes Xi (r. 660–627 BC) and Wen (r. 627–609 BC).[10] By 562 BC, under Duke Xiang (r. 573–542 BC), the families created private armies and fortified their palaces, effectively partitioning ducal authority and weakening central control.[10] In 537 BC, they divided Lu's territory into four parts, with the Jisun controlling two and implementing a field tax system, while the others relied on corvée labor or mixed methods, solidifying their dominance over governance and military affairs.[10] Subsequent dukes attempted to reclaim power but faced exile or failure; Duke Zhao (r. 542–510 BC) clashed with the Three Huan, leading to his flight to Qi and eventual death in exile, while Duke Ding (r. 510–495 BC) sought to curb their influence through alliances and reforms.[1] During Duke Ding's reign, Confucius (born 551 BC in Lu) briefly served as a minister of justice and intervened in 500 BC to oppose the Jisun clan's attack on the recalcitrant district of Zhuan Yu, advocating restraint to avoid broader instability.[1] He also advised against ceding border territories to Qi to avert invasion, though his efforts to restore ritual order and ducal authority ultimately failed, prompting his departure from Lu around 497 BC.[1] Under Duke Ai (r. 495–467 BC), the last ruler chronicled in the Annals, Lu endured continued pressure from the Three Huan and external threats from Wu and Qi, with the families' control preventing effective resistance and contributing to the state's diminished role among Zhou vassals.[1] These internal power shifts exemplified the broader fragmentation of Zhou feudal authority, as noble clans prioritized lineage interests over the duke's, leading to Lu's reliance on diplomacy rather than military expansion.[10]Decline in the Warring States Period

During the early Warring States period, Lu under Duke Mu (r. 408–377 BC) saw a restoration of ducal authority over the dominant Three Huan clans (Shusun, Jisun, and Mengsun), which had controlled the state since the Spring and Autumn era.[1] Duke Mu participated in military campaigns against the neighboring state of Qi, temporarily bolstering Lu's position amid the era's interstate rivalries.[1] However, this revival proved short-lived, as Lu remained a minor power lacking the resources for the large-scale armies, administrative reforms, and iron weaponry that characterized stronger states like Qin, Chu, and Qi.[2] Subsequent rulers faced persistent internal fragmentation from the noble clans and external pressures, leading to territorial losses. Lu ceded towns and villages to Qi and Wu, while escalating conflicts with the expanding Chu state—driven indirectly by Qin's westward campaigns forcing Chu eastward—further eroded its sovereignty.[1] By the late 3rd century BC, under Duke Qing (r. 273–255 BC), Lu's military and economic weakness made it vulnerable to conquest, with no significant alliances or innovations to counter the professionalized warfare of the period.[1] In 249 BC, Chu under King Kaolie invaded and annexed Lu, extinguishing the state after nearly 800 years of existence.[2] Duke Qing, the final ruler, was deposed and reduced to commoner status, marking the end of the Ji clan's direct rule in Lu.[1] This conquest reflected broader patterns of consolidation among the Warring States' major powers, where smaller entities like Lu were absorbed without prolonged resistance.[2]Rulers and Political Structure

List of Dukes and Reigns

The state of Lu was governed by dukes from the Ji clan, tracing descent from the Duke of Zhou (Ji Dan), who enfeoffed his son Boqin as the first hereditary ruler around the 11th century BCE during the Western Zhou dynasty.[1] Reign lengths and successions are documented in primary sources like Sima Qian's Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian), cross-referenced with the Spring and Autumn Annals, though early dates are approximate due to limited contemporaneous records, and later ones align more closely with the Chunqiu era (722–481 BCE).[1] Internal power struggles, including usurpations and assassinations, frequently disrupted orderly succession, particularly from the 8th century BCE onward, as noble clans like the Three Huan gained influence.[1]| Duke Title | Reign (BCE) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Boqin (Duke of Lu) | ca. 1042–1013 | Son of Duke of Zhou; established administrative control over Lu territory.[1] |

| Gao | ca. 1013–? | Early successor; limited records.[1] |

| Shang | ? | -[1] |

| You | ? | -[1] |

| Wei | ? | -[1] |

| Li | ? | -[1] |

| Xian | ? | -[1] |

| Zhen | ca. 856–826 | -[1] |

| Wu | 826–816 | Succession dispute with Duke Yi.[1] |

| Yi | 816–807 | Assassinated by Prince Boya's supporters.[1] |

| Boya (usurper) | 807–796 | Executed by Zhou King Xuan for usurpation.[1] |

| Xiao | 796–769 | Selected for moral conduct post-usurpation.[1] |

| Hui | 769–723 | -[1] |

| Yin | 723–712 | First duke in Spring and Autumn Annals; assassinated.[1] |

| Huan | 712–694 | Killed by Qi's Duke Xiang amid scandal.[1] |

| Zhuang | 694–662 | Allied with smaller states; slew Qi's Prince Jiu.[1] |

| Min (Ji Ban) | 662 | Assassinated by Qing Fu.[1] |

| Min (Ji Qifang) | 662–660 | Brief reign.[1] |

| Xi | 660–627 | Emergence of Three Huan clans (Shusun, Jisun, Mengsun).[1] |

| Wen I | 627–609 | -[1] |

| Xuan | 609–591 | Reforms attempted.[1] |

| Cheng | 591–573 | Introduced tax and military reforms.[1] |

| Xiang | 573–542 | Era of Confucius's birth (551 BCE).[1] |

| Zhao | 542–510 | Exiled to Qi and Jin; died in exile.[1] |

| Ding | 510–495 | Struggles with Three Huan and Qi influence.[1] |

| Ai | 495–467 | Confucius's death (479 BCE); defeats by Wu and Qi.[1] |

| Dao | 467–429 | -[1] |

| Yuan | 429–408 | -[1] |

| Mu | 408–377 | Temporary ducal power restoration; clashes with Chu.[1] |

| Gong | 377–353 | -[1] |

| Kang | 353–344 | -[1] |

| Jing | 344–315 | -[1] |

| Ping | 315–296 | -[1] |

| Wen II (or Min) | 296–273 | -[1] |

| Qing | 273–255 | Final duke; Lu annexed by Chu in 255 BCE, he demoted to commoner status.[1] |