Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

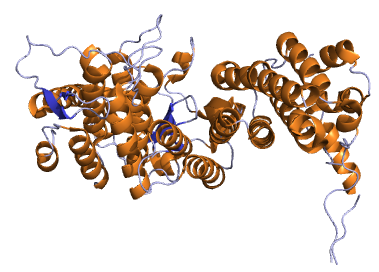

Menin is a protein that in humans is encoded by the MEN1 gene.[5] Menin is a putative tumor suppressor associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1 syndrome) and has autosomal dominant inheritance.[6] Variations in the MEN1 gene can cause pituitary adenomas, hyperparathyroidism, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors, gastrinoma, and adrenocortical cancers.

In vitro studies have shown that menin is localized to the nucleus, possesses two functional nuclear localization signals, and inhibits transcriptional activation by JunD. However, the function of this protein is not known. Two messages have been detected on northern blots but the larger message has not been characterized. Two variants of the shorter transcript have been identified where alternative splicing affects the coding sequence. Five variants where alternative splicing takes place in the 5' UTR have also been identified.[5]

History

[edit]In 1988, researchers at Uppsala University Hospital and the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm mapped the MEN1 gene to the long arm of chromosome 11.[7] The gene was finally cloned in 1997.[8]

Genomics

[edit]The gene is located on long arm of chromosome 11 (11q13) between base pairs 64,570,985 and 64,578,765. It has 10 exons and encodes a 610-amino acid protein.

Over 1300 mutations have been reported to date (2010). The majority (>70%) of these are predicted to lead to truncated forms are scattered throughout the gene. Four - c.249_252delGTCT (deletion at codons 83-84), c.1546_1547insC (insertion at codon 516), c.1378C>T (Arg460Ter) and c.628_631delACAG (deletion at codons 210-211) have been reported to occur in 4.5%, 2.7%, 2.6% and 2.5% of families.[6]

Clinical implications

[edit]The MEN1 phenotype is inherited via an autosomal-dominant pattern and is associated with neoplasms of the pituitary gland, the parathyroid gland, and the pancreas (the 3 "P"s). While these neoplasias are often benign (in contrast to tumours occurring in MEN2A), they are adenomas and, therefore, produce endocrine phenotypes. Pancreatic presentations of the MEN1 phenotype may manifest as Zollinger–Ellison syndrome.

MEN1 pituitary tumours are adenomas of anterior cells, typically prolactinomas or growth hormone-secreting. Pancreatic tumours involve the islet cells, giving rise to gastrinomas or insulinomas. In rare cases, adrenal cortex tumours are also seen.

Role in cancer

[edit]Most germline or somatic mutations in the MEN1 gene predict truncation or absence of encoded menin resulting in the inability of MEN1 to act as a tumor suppressor gene.[9] Such mutations in MEN1 have been associated with defective binding of encoded menin to proteins implicated in genetic and epigenetic mechanisms.[10] Menin is a 621 amino acid protein associated with insulinomas[11] which acts as an adapter while also interacting with partner proteins involved in vital cell activities such as transcriptional regulation, cell division, cell proliferation, and genome stability. Insulinomas are neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas with an incidence of 0.4 %[citation needed] which usually are benign solitary tumors but 5-12 % of cases have distant metastasis at diagnosis.[12] These familial MEN-1 and sporadic tumors may arise either due to loss of heterozygosity or the chromosome region 11q13 where MEN1 is located, or due to presence of mutations in the gene.[13][14]

MEN1 mutations comprise mostly frameshift deletions or insertions, followed by nonsense, missense, splice-site mutations and either part or complete gene deletions resulting in disease pathology.[15] Frameshift and nonsense mutations result in a supposed inactive and truncated menin protein while splice-site mutations result in incorrectly spliced mRNA. Missense mutations of MEN1 are especially important as they result in a change to crucial amino acids needed in order to bind and interact with other proteins and molecules. As menin is located predominantly in the nucleus,[16] these mutations can impact the stability of the cell and may further affect functional activity or expression levels of the protein. Studies have also shown that single amino acid changes in genes involved in oncogenic disorders may result in proteolytic degradation leading to loss of function and reduced stability of the mutant protein; a common mechanism for inactivating tumor suppressor gene products.[17][18] MEN1 gene mutations and deletions also play a role in the development of hereditary and a subgroup of sporadic pituitary adenomas and were detected in approximately 5% of sporadic pituitary adenomas.[19] Consequently, alterations of the gene represent a candidate pathogenetic mechanism of pituitary tumorigenesis especially when considered in terms of interactions with other proteins, growth factors, oncogenes play a rule in tumorigenesis.

Although the exact function of MEN1 is not known, the Knudson "two-hit" hypothesis provides strong evidence that it is a tumor suppressor gene. Familial loss of one copy of MEN1 is seen in association with MEN-1 syndrome. Tumor suppressor carcinogenesis follows Knudson's "two-hit" model.[20] The first hit is a heterozygous MEN1 germline mutation either developed in an early embryonic stage and consequently present in all cells at birth for the sporadic cases, or inherited from one parent in a familial case. The second hit is a MEN1 somatic mutation, oftentimes a large deletion occurring in the predisposed endocrine cell and providing cells with the survival advantaged needed for tumor development.[21] The MEN-1 syndrome often exhibits tumors of parathyroid glands, anterior pituitary, endocrine pancreas, and endocrine duodenum. Less frequently, neuroendocrine tumors of lung, thymus, and stomach or non-endocrine tumors such as lipomas, angiofibromas, and ependymomas are observed neoplasms.[22]

In a study of 12 sporadic carcinoid tumors of the lung, five cases involved inactivation of both copies of the MEN1 gene. Of the five carcinoids, three were atypical and two were typical. The two typical carcinoids were characterized by a rapid proliferative rate with a higher mitotic index and stronger Ki67 positivity than the other typical carcinoids in the study. Consequently, the carcinoid tumors with MEN1 gene inactivation in the study were considered to be characterized by more aggressive molecular and histopathological features than those without MEN1 gene alterations.[23]

Pharmaceuticals

[edit]Anticancer drugs that exert their pharmacological effect by interfering with menin's interactions include the approved drug revumenib and the experimental drugs enzomenib, icovamenib, and ziftomenib.

Interactions

[edit]MEN1 has been shown to interact with:

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000133895 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000024947 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: MEN1 multiple endocrine neoplasia I".

- ^ a b Thakker RV (June 2010). "Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1)". Best Practice & Research. Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 24 (3): 355–70. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2010.07.003. PMID 20833329.

- ^ Byström C, Larsson C, Blomberg C, Sandelin K, Falkmer U, Skogseid B, Oberg K, Werner S, Nordenskjöld M (March 1990). "Localization of the MEN1 gene to a small region within chromosome 11q13 by deletion mapping in tumors". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 87 (5): 1968–72. Bibcode:1990PNAS...87.1968B. doi:10.1073/pnas.87.5.1968. PMC 53606. PMID 1968641.

- ^ Chandrasekharappa SC, Guru SC, Manickam P, Olufemi SE, Collins FS, Emmert-Buck MR, Debelenko LV, Zhuang Z, Lubensky IA, Liotta LA, Crabtree JS, Wang Y, Roe BA, Weisemann J, Boguski MS, Agarwal SK, Kester MB, Kim YS, Heppner C, Dong Q, Spiegel AM, Burns AL, Marx SJ (April 1997). "Positional cloning of the gene for multiple endocrine neoplasia-type 1". Science. 276 (5311): 404–7. doi:10.1126/science.276.5311.404. PMID 9103196.

- ^ Agarwal SK, Lee Burns A, Sukhodolets KE, Kennedy PA, Obungu VH, Hickman AB, Mullendore ME, Whitten I, Skarulis MC, Simonds WF, Mateo C, Crabtree JS, Scacheri PC, Ji Y, Novotny EA, Garrett-Beal L, Ward JM, Libutti SK, Richard Alexander H, Cerrato A, Parisi MJ, Santa Anna-A S, Oliver B, Chandrasekharappa SC, Collins FS, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ (April 2004). "Molecular pathology of the MEN1 gene". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1014 (1): 189–98. Bibcode:2004NYASA1014..189A. doi:10.1196/annals.1294.020. PMID 15153434. S2CID 27333205.

- ^ Jyotsna VP, Malik E, Birla S, Sharma A (2015-01-01). "Novel MEN 1 gene findings in rare sporadic insulinoma--a case control study". BMC Endocrine Disorders. 15: 44. doi:10.1186/s12902-015-0041-2. PMC 4549893. PMID 26307114.

- ^ Chandrasekharappa SC, Guru SC, Manickam P, Olufemi SE, Collins FS, Emmert-Buck MR, Debelenko LV, Zhuang Z, Lubensky IA, Liotta LA, Crabtree JS, Wang Y, Roe BA, Weisemann J, Boguski MS, Agarwal SK, Kester MB, Kim YS, Heppner C, Dong Q, Spiegel AM, Burns AL, Marx SJ (April 1997). "Positional cloning of the gene for multiple endocrine neoplasia-type 1". Science. 276 (5311): 404–7. doi:10.1126/science.276.5311.404. PMID 9103196.

- ^ Schussheim DH, Skarulis MC, Agarwal SK, Simonds WF, Burns AL, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ (2001-06-01). "Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1: new clinical and basic findings". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 12 (4): 173–8. doi:10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00372-6. PMID 11295574. S2CID 32447772.

- ^ Thakker RV (April 2014). "Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) and type 4 (MEN4)". Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 386 (1–2): 2–15. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2013.08.002. PMC 4082531. PMID 23933118.

- ^ Friedman E, Sakaguchi K, Bale AE, Falchetti A, Streeten E, Zimering MB, Weinstein LS, McBride WO, Nakamura Y, Brandi ML (July 1989). "Clonality of parathyroid tumors in familial multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1". The New England Journal of Medicine. 321 (4): 213–8. doi:10.1056/nejm198907273210402. PMID 2568586.

- ^ Lemos MC, Thakker RV (January 2008). "Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1): analysis of 1336 mutations reported in the first decade following identification of the gene". Human Mutation. 29 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1002/humu.20605. PMID 17879353. S2CID 394253.

- ^ Guru SC, Manickam P, Crabtree JS, Olufemi SE, Agarwal SK, Debelenko LV (June 1998). "Identification and characterization of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) gene". Journal of Internal Medicine. 243 (6): 433–9. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00346.x. PMID 9681840. S2CID 23149408.

- ^ Agarwal SK, Guru SC, Heppner C, Erdos MR, Collins RM, Park SY, Saggar S, Chandrasekharappa SC, Collins FS, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ, Burns AL (January 1999). "Menin interacts with the AP1 transcription factor JunD and represses JunD-activated transcription". Cell. 96 (1): 143–52. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80967-8. PMID 9989505. S2CID 18116746.

- ^ Yaguchi H, Ohkura N, Tsukada T, Yamaguchi K (2002). "Menin, the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 gene product, exhibits GTP-hydrolyzing activity in the presence of the tumor metastasis suppressor nm23". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (41): 38197–204. doi:10.1074/jbc.M204132200. PMID 12145286.

- ^ Zhuang Z, Ezzat SZ, Vortmeyer AO, Weil R, Oldfield EH, Park WS, Pack S, Huang S, Agarwal SK, Guru SC, Manickam P, Debelenko LV, Kester MB, Olufemi SE, Heppner C, Crabtree JS, Burns AL, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ, Chandrasekharappa SC, Collins FS, Emmert-Buck MR, Liotta LA, Asa SL, Lubensky IA (December 1997). "Mutations of the MEN1 tumor suppressor gene in pituitary tumors". Cancer Research. 57 (24): 5446–51. PMID 9407947.

- ^ Knudson AG (December 1993). "Antioncogenes and human cancer". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (23): 10914–21. Bibcode:1993PNAS...9010914K. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.23.10914. PMC 47892. PMID 7902574.

- ^ Marx SJ, Agarwal SK, Kester MB, Heppner C, Kim YS, Emmert-Buck MR, Debelenko LV, Lubensky IA, Zhuang Z, Guru SC, Manickam P, Olufemi SE, Skarulis MC, Doppman JL, Alexander RH, Liotta LA, Collins FS, Chandrasekharappa SC, Spiegel AM, Burns AL (June 1998). "Germline and somatic mutation of the gene for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1)". Journal of Internal Medicine. 243 (6): 447–53. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00348.x. PMID 9681842. S2CID 20132064.

- ^ Metz DC, Jensen RT, Bale AE, Skarulis MC, Eastman RC, Nieman L, Norton JA, Friedman E, Larsson C, Amorosi A, Brandi ML, Marx SJ (1994). "Multiple endocrine neoplasia type I. Clinical features and management". In Bilezikian JP, Levine MA, Marcus, R (eds.). The Parathyroids. New York: Raven Press Publishing Co. pp. 591–646.

- ^ Debelenko LV, Brambilla E, Agarwal SK, Swalwell JI, Kester MB, Lubensky IA, Zhuang Z, Guru SC, Manickam P, Olufemi SE, Chandrasekharappa SC, Crabtree JS, Kim YS, Heppner C, Burns AL, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ, Liotta LA, Collins FS, Travis WD, Emmert-Buck MR (December 1997). "Identification of MEN1 gene mutations in sporadic carcinoid tumors of the lung". Human Molecular Genetics. 6 (13): 2285–90. doi:10.1093/hmg/6.13.2285. PMID 9361035.

- ^ Jin S, Mao H, Schnepp RW, Sykes SM, Silva AC, D'Andrea AD, Hua X (July 2003). "Menin associates with FANCD2, a protein involved in repair of DNA damage". Cancer Research. 63 (14): 4204–10. PMID 12874027.

- ^ a b Heppner C, Bilimoria KY, Agarwal SK, Kester M, Whitty LJ, Guru SC, Chandrasekharappa SC, Collins FS, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ, Burns AL (August 2001). "The tumor suppressor protein menin interacts with NF-kappaB proteins and inhibits NF-kappaB-mediated transactivation". Oncogene. 20 (36): 4917–25. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204529. PMID 11526476. S2CID 44195141.

- ^ Agarwal SK, Guru SC, Heppner C, Erdos MR, Collins RM, Park SY, Saggar S, Chandrasekharappa SC, Collins FS, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ, Burns AL (January 1999). "Menin interacts with the AP1 transcription factor JunD and represses JunD-activated transcription". Cell. 96 (1): 143–52. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80967-8. PMID 9989505. S2CID 18116746.

- ^ Yokoyama A, Wang Z, Wysocka J, Sanyal M, Aufiero DJ, Kitabayashi I, Herr W, Cleary ML (July 2004). "Leukemia proto-oncoprotein MLL forms a SET1-like histone methyltransferase complex with menin to regulate Hox gene expression". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 24 (13): 5639–49. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.13.5639-5649.2004. PMC 480881. PMID 15199122.

- ^ Sukhodolets KE, Hickman AB, Agarwal SK, Sukhodolets MV, Obungu VH, Novotny EA, Crabtree JS, Chandrasekharappa SC, Collins FS, Spiegel AM, Burns AL, Marx SJ (January 2003). "The 32-kilodalton subunit of replication protein A interacts with menin, the product of the MEN1 tumor suppressor gene". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 23 (2): 493–509. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.2.493-509.2003. PMC 151531. PMID 12509449.

- ^ Lopez-Egido J, Cunningham J, Berg M, Oberg K, Bongcam-Rudloff E, Gobl A (August 2002). "Menin's interaction with glial fibrillary acidic protein and vimentin suggests a role for the intermediate filament network in regulating menin activity". Experimental Cell Research. 278 (2): 175–83. doi:10.1006/excr.2002.5575. PMID 12169273.

Further reading

[edit]- Tsukada T, Yamaguchi K, Kameya T (2002). "The MEN1 gene and associated diseases: an update". Endocrine Pathology. 12 (3): 259–73. doi:10.1385/EP:12:3:259. PMID 11740047. S2CID 30681290.

- Kong C, Ellard S, Johnston C, Farid NR (November 2001). "Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1Burin from Mauritius: a novel MEN1 mutation". Journal of Endocrinological Investigation. 24 (10): 806–10. doi:10.1007/bf03343931. PMID 11765051. S2CID 71097157.

- Thakker RV (2002). "Multiple endocrine neoplasia". Hormone Research. 56 (Suppl 1): 67–72. doi:10.1159/000048138. PMID 11786689. S2CID 85195319.

- Stowasser M, Gunasekera TG, Gordon RD (December 2001). "Familial varieties of primary aldosteronism". Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology & Physiology. 28 (12): 1087–90. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1681.2001.03574.x. PMID 11903322. S2CID 23091842.

- Kameya T, Tsukada T, Yamaguchi K (2004). "Recent Advances in MEN 1 Gene Study for Pituitary Tumor Pathogenesis". Recent advances in MEN1 gene study for pituitary tumor pathogenesis. Frontiers of Hormone Research. Vol. 32. pp. 265–91. doi:10.1159/000079050. ISBN 3-8055-7740-0. PMID 15281352.

- Balogh K, Rácz K, Patócs A, Hunyady L (November 2006). "Menin and its interacting proteins: elucidation of menin function". Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism. 17 (9): 357–64. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2006.09.004. PMID 16997566. S2CID 8063335.

- Lytras A, Tolis G (2006). "Growth hormone-secreting tumors: genetic aspects and data from animal models". Neuroendocrinology. 83 (3–4): 166–78. doi:10.1159/000095525. PMID 17047380. S2CID 45606794.

External links

[edit]- GeneReviews/NIH/NCBI/UW entry on Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1

- MEN1 gene variant database Archived 2017-10-10 at the Wayback Machine

- MEN1+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: O00255 (Menin) at the PDBe-KB.