Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

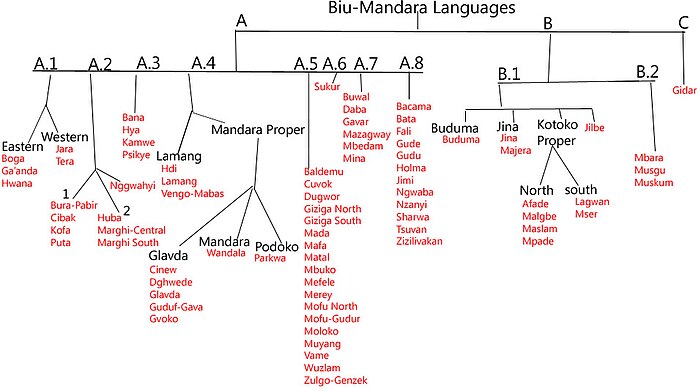

Biu–Mandara languages

View on Wikipedia| Biu–Mandara | |

|---|---|

| Central Chadic | |

| Geographic distribution | Nigeria, Chad, Cameroon |

| Linguistic classification | Afro-Asiatic

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Central Chadic |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | bium1280 |

The Biu–Mandara or Central Chadic languages of the Afro-Asiatic family are spoken in Nigeria, Chad and Cameroon.

A reconstruction of Proto-Central Chadic has been proposed by Gravina (2014).[1]

Languages

[edit]Gravina (2014)

[edit]Gravina (2014) classifies Central Chadic as follows, as part of a reconstruction of the proto-language. Letters and numbers in parentheses correspond to branches in previous classifications. The greatest changes are breaking up and reassigning the languages of the old Mafa branch (A.5) and Mandage (Kotoko) branch (B.1).[2]

- Central Chadic

- South

- Hurza

- North

- Margi–Mandara–Mofu

- Margi (A.2)

- Mandara (A.4):

- Mofu (part of South A.5 Mafa)

- Tokombere: Ouldeme, Mada, Muyang, Molokwo

- Meri: Zulgo, Gemzek, Merey, Dugwor

- Mofu Proper: Mofu North, Mofu-Gudur

- Maroua

- Maroua (part of South A.5 Mafa (c)): Giziga North, Giziga South, Mbazla

- Lamang

- Higi

- Higi (A.3): Bana, Hya, Psikyɛ, Kamwe, Kirya-Konzel

- Musgum – North Kotoko

- Kotoko Centre

- Kotoko South

- Gidar

- Margi–Mandara–Mofu

Jilbe was not classified, as no sources were available.

Blench (2006)

[edit]The branches of Biu–Mandara traditionally go by either names or letters and numbers in an outline format. Blench (2006) organizes them as follows:[4]

- Biu–Mandara

- Tera (A.1): Tera, Pidlimdi (Hinna), Jara, Ga'anda, Gabin, Boga, Ngwaba, Hwana

- Bura–Higi

- Bura (A.2): Bura-Pabir (Bura), Cibak (Kyibaku), Nggwahyi, Huba (Kilba), Putai (Marghi West), Marghi Central (Margi, Margi Babal), Marghi South

- ? Kofa

- Higi (A.3): Kamwə (Psikyɛ, Higi), Bana, Hya, ? Kirya-Konzəl

- Wandala–Mafa

- Wandala (Mandara) (A.4)

- Mafa (A.5)

- Northeast Mafa: Vame (Pəlasla), Mbuko, Gaduwa

- Matal (Muktele)

- South Mafa

- (a) Wuzlam (Ouldémé), Muyang, Maɗa, Məlokwo

- (b) Zəlgwa-Minew, Gemzek, Ɗugwor, Mikere, Merey

- (c) North Giziga, South Giziga, North Mofu, Mofu-Gudur (South Mofu), Baldemu (Mbazlam)

- (d) Cuvok, Mafa, Mefele, Shügule

- Daba (A.7)

- Bata (Gbwata) (A.8): Bacama, Bata (Gbwata), Sharwa, Tsuvan, Gude, Fali of Mubi, Zizilivakan (Ulan Mazhilvən, Fali of Jilbu), Jimi (Jimjimən), Gudu, Holma (†), Nzanyi

- Mandage (Kotoko) (B.1)

- Buduma (Yedina)

- East–Central

Newman (1977)

[edit]Central Chadic classification per Newman (1977):

Names and locations (Nigeria)

[edit]Below is a list of language names, populations, and locations (in Nigeria only) from Blench (2019).[5]

| Branch | Code | Primary locations |

|---|---|---|

| Tera | A1 | Gombi LGA, Adamawa State and Biu LGA, Borno State |

| Bata | A8 | Mubi LGA, Adamawa State |

| Higi | A3 | Michika LGA, Adamawa State |

| Mandara | A4 | Gwoza LGA, Borno State and Michika LGA, Adamawa State |

South

[edit]| Language | Branch | Cluster | Dialects | Alternate spellings | Own name for language | Endonym(s) | Other names (location-based) | Other names for language | Exonym(s) | Speakers | Location(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daba | Daba | Daba | A single village, less than 1,000. Mostly in Cameroun | Adamawa State, Mubi LGA. Between Mubi and Bahuli | ||||||||

| Mafa | Mafa | Mafa (Mofa) in Nigeria. Cameroon dialects divided into West, Central and Eastern. | Mofa | Matakam (not recommended) | 2,000 (1963), 136,000 in Cameroon (1982 SIL) | Borno State, Gwoza LGA; mainly in Cameroon | ||||||

| Sakun | Sukur | Sakun, Gemasakun | Gә̀mà Sákún | Sugur | Adikummu Sukur | 5,000 (1952); 10,000 (1973 SIL). 7 villages | Adamawa State, Madgali LGA | |||||

| Ga’anda cluster | Tera | Ga’anda | Tlәka’andata pl. Ka’andәca | Kaɓәn | Mokar [name of the place where the rolling pot stopped] | 7,600 (1952); 10,000 (1973 SIL);␣4. Six villages | Adamawa State, Gombi LGA | |||||

| Kaɓәn | Tera | Ga’anda | Gabin | Tlәkaɓәnɗa pl. Kaɓәnca | 12 villages | |||||||

| Fәrtata | Tera | Ga’anda | Tlәfәrtata pl. Fәrtaca | 5 villages | ||||||||

| Boga | Tera | Boka | 5 villages | Adamawa State, Gombi LGA | ||||||||

| Hwana | Tera | Hona, Hwona | 6,604 (1952 W&B); 20,000 (1973 SIL), estimate more than 20,000 (Blench 1987) | Adamawa State, Gombi LGA, Guyuk and 30 other villages | ||||||||

| Jara | Tera | Jera | 4,000 (SIL) | Borno State, Biu LGA; Bauchi State, Ako LGA | Also refers to the languages of the Jarawan Bantu group including: the Jarawa cluster, Mbárù, Gùra, Rúhû, Gubi, Dulbu, Láb̀r, Kulung, and Gwa | |||||||

| Tera cluster | Tera | Tera | 46,000 (SIL); 50,000 (Newman 1970) | Borno State, Biu LGA; Gombe State, Gombi LGA, Kwami district, Ako LGA, Yamaltu and Ako districts, Dukku LGA, Funakaye district | ||||||||

| Nyimatli | Tera | Tera | Wuyo-Ɓalɓiya-Waɗe; Deba-Zambuk-Hina-Kalshingi-Kwadon [orthography based on this cluster] | Yamaltu, Nimalto, Nyemathi | Gombe State, Ako, Gombe, Kwami, Funakai, Yamaltu LGAs; Borno State, Ɓayo LGA | |||||||

| Pidlimdi | Tera | Tera | Hinna, Hina, Ghәna | Borno State, Biu LGA | ||||||||

| Bura Kokura | Tera | Tera | Borno State, Biu LGA | |||||||||

| Boga | Tera, Eastern | Boka | Adamawa State, Gombi LGA | |||||||||

| Bata cluster | Bata | Bata | ||||||||||

| Bwatye | Bata | Bata | Mulyen (Mwulyin), Dong, Opalo, Wa-Duku | Gboare, Bwatiye | Kwaa–Ɓwaare | Ɓwaare | Bachama | 11,250 (1952) 20,000 (1963) | Adamawa State, Numan and Guyuk LGAs, Kaduna State, north east of Kaduna town. Bacama fishermen migrate long distances down the Benue River, with camps as far as the Benue/Niger confluence. | |||

| Bata | Bata | Bata | Koboci, Kobotschi (Kobocĩ, Wadi, Zumu (Jimo), Malabu, Bata of Ribaw, Bata of Demsa, Bata of Garoua, Jirai | Batta, Gbwata | 26,400 (1952), est. 2,000 in Cameroon; 39,000 total (1971 Welmers) | Adamawa State, Numan, Song, Fufore and Mubi LGAs; also in Cameroon | ||||||

| Fali cluster | Bata | Fali | Fali of Mubi, Fali of Muchella | Vimtim, Yimtim | 4 principal villages. Estimate of more than 20,000 (1990) | Adamawa State, Mubi LGA | ||||||

| Vin | Bata | Fali | Uroovin | Uvin | Vimtim | Vimtim town, north of Mubi | ||||||

| Huli | Bata | Fali | Bahuli | Urahuli | Huli, Hul | Bahuli town, northeast of Mubi | ||||||

| Madzarin | Bata | Fali | Ura Madzarin | Madzarin | Muchella | Muchella town, northeast of Mubi | ||||||

| Ɓween | Bata | Fali | Uramɓween | Cumɓween | Bagira | Bagira town, northeast of Mubi | ||||||

| Gudu | Bata | Gutu, Gudo | 1,200 (LA 1971) | Adamawa State, Song LGA, 120 km. west of Song. Approximately 5 villages. | ||||||||

| Guɗe | Bata | Gude, Goudé | Mubi | Cheke, Tcheke, Mapuda, Shede, Tchade, Mapodi, Mudaye, Mocigin, Motchekin | 28,000 (1952), est. 20,000 in Cameroon | Adamawa State, Mubi LGA; Borno State, Askira–Uba LGA; and in Cameroon | ||||||

| Holma | Bata | Holma | Da Holmaci | Bali Holma | 4 speakers (Blench, 1987). The language has almost vanished and has been replaced by Fulfulde. | Adamawa State. Spoken north of Sorau on the Cameroon border | ||||||

| Ngwaba | Bata | Gombi, Goba | Fewer than 1000 | Adamawa State, Gombi LGA, at Fachi and Gudumiya | ||||||||

| Nzanyi | Bata | Paka, Rogede (Rɨgudede), Nggwoli, Hoode, Maiha, Magara, Dede, Mutidi; and Lovi in Cameroon | Njanyi, Njai, Njei, Zany, Nzangi, Zani, Njeny, Jeng, Njegn, Njeng, | Nzangɨ sg., Nzanyi pl. | Jenge, Jeng, Mzangyim, Kobochi, Kobotshi | 1.B Wur Nzanyi | 14,000 in Nigeria (1952), 9,000 in Cameroon. | Nigeria: Adamawa State, Maiha LGA. Cameroon: West of Dourbeye near Nigerian border in Doumo region, Mayo-Oulo Subdivision, Mayo-Louti Division, North Province. | ||||

| Zizilivәkan | Bata | Zilivә | ÀmZírív | Fali of Jilbu | ‘a few hundred’ in Cameroon | Adamawa State, Mubi LGA, Jilbu town; and in Cameroon |

North

[edit]| Language | Branch | Cluster | Dialects | Alternate spellings | Own name for language | Endonym(s) | Other names (location-based) | Other names for language | Exonym(s) | Speakers | Location(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huba | Bura | Luwa | Hәba | Huba | Huba | Chobba Kilba | 32,000 (1952); 100,000 (1980 UBS) | Adamawa State, Hong, Maiha, Mubi and Gombi LGAs | ||||

| Margi | Bura | Central: Margi babal = ‘Margi of the Plain’ around Lasa, Margi Dzәrŋu = ‘Margi near the Hill öu’ around Gulak; Gwàrà; Mə̀lgwí (Mulgwe, Molgheu); Wúrgà (Urga); South Margi is counted as a separate language and is more closely related to Huba | Marghi, Margyi | Màrgí | Màrgí | For Margi, Margi South and Putai: 135,000 (1955); 200,000 (1987 UBS) | Borno State, Askira–Uba and Damboa LGAs; Adamawa State, Madagali, Mubi and Michika LGAs | |||||

| Nggwahyi | Bura | Ngwaxi, Ngwohi | One village | Borno State, Askira–Uba LGA | ||||||||

| Putai | Bura | Margi West | Margi Putai = ‘West Margi’, Margi of Minthla | Language dying out, but ethnic population large | Borno State, Damboa LGA | |||||||

| Margi South | Bura | Wamdiu, Hildi | Margi ti ntәm | For Margi, Margi South and Putai: 135,000 (1955) | Borno State, Askira–Uba LGA; Adamawa State, Mubi and Michika LGAs | Hoffmann (1963) relates the language of Margi South to Huba rather than to Margi. | ||||||

| Bura–Pabir | Bura | Bura Pela (Hill Bura), Bura Hyil Hawul (Plains Bura) | Bourrah, Burra, Babir, Babur | Mya Bura | Two peoples with one language: the Bura and the Pabir | Kwojeffa, Huve, Huviya | 72,200 (1952 W&B), 250,000 (1987 UBS) | Borno State, Biu and Askira–Uba LGAs | ||||

| Cibak | Bura | Chibak, Chibuk, Chibbuk, Chibbak, Kyibaku, Kibaku | Cíbɔ̀k, Kikuk | 20,000 (1973 SIL) | Borno State, Damboa LGA, south of Damboa town | |||||||

| Kamwe | Higi | Nkafa, Dakwa (Bazza), Sәna, Wula, Futu, Tili Pte, Kapsiki (Ptsәkɛ) in Cameroon | Vәcәmwe | Higi, Hiji, Kapsiki | 64,000 (1952); 180,000 (1973 SIL) est. 23,000 in Cameroon | Adamawa State, Michika LGA and into Cameroon | ||||||

| Mukta | Higi | Kamwe | Mukta | Mukta village | Adamawa State | |||||||

| Kirya-Konzәl cluster | Higi | Kirya-Konzәl | Fali | Adamawa State, Michika LGA. | ||||||||

| Kirya | Higi | Kirya-Konzәl | myá Kákíryà | ndá Kákìryà pl. Kákìryà | Fali of Kiriya | 7,000 est. 2007. Kirya: 13 villages | ||||||

| Konzәl | Higi | Kirya-Konzәl | myá Kónzә̀l | ndá Kónzә̀l pl. Kónzә̀l | Fali of Mijilu | 9000 est. 2007. Konzәl: 15 villages | ||||||

| Cinene | Mandara | Cinene | Cinene | 3200 (Kim 2001) | Borno State, Gwoza LGA, east of Gwoza town in the mountains. 5 villages. | |||||||

| Dghweɗe | Mandara | Dghwede, Hude, Johode, Dehoxde, Tghuade, Toghwede, Traude | Dghwéɗè | Azaghvana, Wa’a, Zaghvana | 19,000 (1963), 7,900 (TR 1970), 30,000 (1980 UBS) | Borno State, Gwoza LGA | ||||||

| Guduf–Cikide cluster | Mandara | Guduf–Cikide | Afkabiye (Lamang) | 21,300 (1963) | Borno State, Gwoza LGA, east of Gwoza town in the mountains. Six main villages. | |||||||

| Guduf | Mandara | Guduf–Cikide | Guduf, Cikide (Chikide) | Kәdupaxa | Ɓuxe, Gbuwhe, Latәghwa (Lamang), Lipedeke (Lamang). Also applied to Dghwede. | |||||||

| Gava | Mandara | Guduf–Cikide | Gawa | Kәdupaxa | Linggava, Ney Laxaya, Yaghwatadaxa, Yawotataxa, Yawotatacha, Yaxmare, Wakura | |||||||

| Cikide | Mandara | Guduf–Cikide | Cikide | Cikide | ||||||||

| Gvoko | Mandara | Gәvoko | Ngoshe Ndaghang, Ngweshe Ndhang, Nggweshe | Ngoshe Sama | 2,500 (1963); 4,300 (1973 SIL); estimated more than 20,000 (1990) | Borno State, Gwoza LGA; Adamawa State, Michika LGA | ||||||

| Lamang cluster | Mandara | Lamang | Laamang | Waha | 15,000 (TR 1970), 40,000 (1963) | |||||||

| Zaladva | Mandara | Lamang | Zaladeva (Alataghwa), Dzuuɓa (Dzuuba), Lәghva (Lughva), Gwózà Wakane (Gwozo) | Zәlәdvә | Lamang North | Borno State, Gwoza LGA | ||||||

| Ghumbagha | Mandara | Lamang | Hә̀ɗkàlà (Xәdkala, Hidkala, Hitkala), Waga (Wagga, Woga, Waha) | Lamang Central | Borno State, Gwoza LGA; Adamawa State, Michika LGA; | |||||||

| Ghudavan | Mandara | Lamang | Ghudeven, Ghudәvәn | Lamang South | Borno State, Gwoza LGA; Adamawa State, Michika LGA; and in Cameroon | |||||||

| Glavda | Mandara | Ngoshe (Ngweshe) | Galavda, Glanda, Gelebda, Gәlәvdә | Wakura | 20,000 (1963); 2,800 in Cameroon (1982 SIL) | Borno State, Gwoza LGA; also in Cameroon | ||||||

| Hdi | Mandara | Hidé, Hide, Xide, Xedi | Xәdi | Gra, Tur, Turu, Tourou, Ftour | Borno State, Gwoza LGA; Adamawa State, Michika LGA; and in Cameroon | |||||||

| Vemgo–Mabas cluster | Mandara | Vemgo–Mabas | ||||||||||

| Vemgo | Mandara | Vemgo–Mabas | Borno State, Gwoza LGA; Adamawa State, Michika LGA; and in Cameroon | |||||||||

| Mabas | Mandara | Vemgo–Mabas | A single village on the Nigeria/Cameroon frontier | Adamawa State, Michika LGA. 10 km. S.E. of Madagali | ||||||||

| Wandala cluster | Mandara | Wandala | Mandara, Ndara | 19,300 in Nigeria (1970); 23,500 in Cameroon (1982 SIL) | Borno State. Bama, Gwoza LGAs. | |||||||

| Wandala | Mandara | Wandala | Wandala | Mandara | Used as a vehicular language in this locality of Nigeria and Cameroon | |||||||

| Mura | Mandara | Wandala | Mura | Mora, Kirdi Mora | An archaic form of Wandala spoken by non–Islamized populations | Uncertain if Mura is spoken in Nigeria | ||||||

| Malgwa | Mandara | Wandala | Gwanje | Mәlgwa | Malgo, Gamargu, Gamergu | 10,000 (TR 1970) | Borno State, Damboa, Gwoza and Konduga LGAs | |||||

| Afaɗә | Mandage | Afade, Affade, Afadee | Afaɗә | Kotoko, Mogari | Twelve villages in Nigeria, estimate Fewer than 20,000 (1990) | Borno State, Ngala LGA; and in Cameroon | ||||||

| Jilbe | Mandage | Jilbe | ? 100 speakers (Tourneux p.c. 1999) | Borno State, a single village on the Nigeria Cameroon border, south of Dikwa | ||||||||

| Yedina | Yedina | Yedina, Kuri (not in Nigeria) | Yídә́nà | Buduma | 20,000 in Chad; 25,000 total (1987 SIL) | Borno State, islands of Lake Chad and mostly in Chad |

Numerals

[edit]Comparison of numerals in individual languages:[6]

| Classification | Language | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A, A.1, Eastern | Boga (Boka) | ɨrtà | cə̀p | məkkən | fwəɗà | ɗurmən | tyɛ̀xxɛɬ | mwut | fwotfwə̀ɗà (2 x 4) | hàhìrta (10–1) | kum |

| A, A.1, Eastern | Ga'anda | ar̃ta (r̃ is a trill) | sur̃r̃i | mahkə̀n | fwəɗà | ɗɨrmən | mɪca | mwùt(n) | fwətfwəɗà (2 x 4) | wə̀nhəhəʔar̃tà (10–1) ? | kum |

| A, A.1, Eastern | Hwana (Hwona) | tìtal | suɣurì | maxə̀n | faɗà | tuf(ù) | mɪ̀ki | mɨɗ(u) | (w)ùvwəɗà (2 x 4) | wùtàrè (10–1) ? | ɡumdìɗi / kum |

| A, A.1, Western | Tera (1) | dà / da | rāp / rap | kúnúŋ / kununɡ | vàt / vat | qúrmún / qurmun | ⁿjòŋ / njoŋ | mút / mut | mʲāsī / myaasi | mɨ̄ɮām / mu̠dlam | ɡʷàŋ / ɡwanɡ |

| A, A.1, Western | Tera (2) | da | rab | kunuk | fad | ɠurmun | njoŋ | mut | miyasi | milam | ɡwan |

| A, A.2 | Nggwahyi (Ngwaxi) | tə̀ŋ | sɪɗà | makùr̃ | fwə̀r̃ | tufù | nkwɔ̀ | mur̃fà | ncis | mɪða | kuma |

| A, A.2, 1 | Bura (Bura-Pabir) (1) | ntànɡ | sùɗà | màkə̀r | fwàr | ntìfù | nkwà | mùrfà | cìsù | ùmðlà | kùmà |

| A, A.2, 1 | Bura (Bura-Pabir) (2) | ntaŋ | suɗà | makùr̃ | fwar̃ | ntufù | ŋ̀kwà | murfà | ncɨsù | ḿðà | kuma |

| A, A.2, 1 | Cibak (Bura-Pabir) | tə̀ŋ / patù / dukù | sudæ̀ | makùr̃ | fwòɗu | tufù | ŋ̀kwà | murɨfwæ̀ | ntsisù | mɨðæ | kuma |

| A, A.2, 1 | Putai (West Margi) | duku / təŋ / duɡu | suɗà / fɨɗɛ̀ | makùr | fɔɗu / fwoɗu | tufù | kwa / kwɔ̀ | muɗufā / muɗɨfɛ̀ | cisù / ncɪsù | ḿðà / mðɛ̀ | kuma / kumɛ |

| A, A.2, 2 | Huba (Kilba) | dzàŋ | mətlù | màkə̀r / màkərù | fòɗù | tùfù | kwà | məɗəfà | cìsù | dlà | kùmà / kùm |

| A, A.2, 2 | Central Marghi | taŋ / paɬu / tɪtɨkù | mɨɬù / sɪɗàŋ | makùr̃ | fwoɗù | ntɪfù | ŋ̀kwà | mɪɗɪfù | ntsisù | ḿðù | kumu |

| A, A.3 | Bana (1) | tánə̀ | bákə̀ | máhə̀kánə̀ | fáɗə̀ | cífə̀ | kwáŋ | bə̀rfàŋ | də̀ɣə̀sə̀ | mə̀ɬísɗə̀ | mə̀ŋ |

| A, A.3 | Bana (2) | kwətiŋ | bakə | mahkan | faɗə | cifə | kwaŋ | mbərfəŋ | dəghəs | məsliɗ | məŋ |

| A, A.3 | Hya (Higi Ghye) | paðɛ / tanɛ | ɓaɡɛ | màŋkɛ | fwaɗɛ | wcivi | kwaŋəy | mbùr̃ùfəŋəy | tùɡùzi | wɨɬti | mùŋəy |

| A, A.3 | Kafa (1) | ʔìkkòó | ɡùttòó | kèèmó | áwùddò | ʔùùttʃòó | ʃírìttòó | ʃábààttòó | ʃímìttòó | jììtʼijòó | ààʃìròó |

| A, A.3 | Kafa (2) | ʔikko | ɡutto | keemo | ʔauddo | ʔuutʃtʃo | ʃiritto | ʃabaatto | ʃimitto | jiitʼijo | ʔaaʃiro |

| A, A.3 | Kafa (3) | ʔikko | ɡutto | keemo | auddo | uuččo | širitto | šabaatto | šimitto | yiitʼtʼio | aaširo |

| A, A.3 | Kwame (Fali of Kiria) | ɡutàn / tanəy | ɓwukuʔ | màkun(u) | fwaɗùʔ | (w)cɪfuʔ | ŋkwaŋ | mbùrùfūŋ | tùɣùsùʔ | ǹwɬti(ʔyì) | ɡwùm(ù) |

| A, A.3 | Psikye (Kapsiki) | kwetɛŋe | bake | mahekene | wəfaɗe | mcɛfe | ŋkwaŋe | mberefaŋe | deɡhese | mesli | meŋe |

| A, A.4, Lamang | Hadi (Hdi) | tèkw | hìs | hə̀kə̀n | fwáɗ | hùtáf | mə̀kúʔ | ndə̀fáŋ | tə̀ɣás | tə̀mbáy / timbe | ɣwàŋ |

| A, A.4, Lamang | Lamang | tíuwá / tálá | χésá | χ̀kə́ná | ùfáɗá | χẁtáfá | m̀kwá / m̀kuwá | ə̀lfáŋá | tə̀ɣásá | tə̀mbáyá | ɣwáŋá |

| A, A.4, Lamang | Vemgo-Mabas | pál / tékw | hés | xə̀kə̀n | úfáɗ | xútáf | ŋ́ku | lə̀fàŋ | tə̀ɣàs | tə̀mbàj | ɣə̀wàŋ |

| A, A.4, Mandara Proper, Glavda | Cinene | pàlà | bùʷà | xə̀kə̀rɗà | ùfàɗà | ɮɨ̀ɓà | ŋkʷàxà | ùɗifà | tə̀ɣsà | vaslambàɗà | klawà |

| A, A.4, Mandara Proper, Glavda | Dghwede | tɨtɨkwì, tekwè | micè | xəkùrè | fiɗì | ðiɓi | ŋ́kwe | wuɗìfi | təɣə̀še / təxəse | təmbə̀ | ɣwàŋɡa |

| A, A.4, Mandara Proper, Glavda | Glavda | páll | bwa | xkərɗ | ufáɗ | ɮəɓ | ŋkwax | uɗif | tə́xs | vaslambaɗ | klàáwá |

| A, A.4, Mandara Proper, Glavda | Guduf-Gava | tekʷè / kitakʷè | mitsè | xəkərɗè | ùfəɗè | ɮɨ̀ɓè | ŋkʷaxè | ùɗifè | tə̀ɣəsè | vaslambàɗè | kuləkè |

| A, A.4, Mandara Proper, Glavda | Gvoko | palò / tekò | xecò | xəkʷarò | fwaɗò | ɮaʔò | ŋkoyò | ntfaŋɡò | tə̀ɣasò | tɨ̀mbayò | ɣʷaŋɡò |

| A, A.4, Mandara Proper, Mandara | Wandala (Malgwa) | pálle | búwa | kəɠyé | ufáɗe | iiɮəbé | unkwé | vúye | tiise | másə́lmane | kəláwa |

| A, A.4, Mandara Proper, Podoko | Podoko | kutəra | səra | makəra | ufaɗa | zlama | məkuwa | maɗəfa | za | metɨrəce | jɨma |

| A, A.5 | Cuvok (Tchouvok) (1) | ámə̀tà | át͡ʃèw | máákàr | fáɗ | ɮám | máákwà | tásə̀là | t͡ʃáákàr | t͡ʃʉ́ɗ | kùràw |

| A, A.5 | Cuvok (Tchouvok) (2) | amta, mta | ɛt͡ʃəw | maakar | faɗ | ɮam | makwa | tasəla | tsaakar | t͡ʃyɗ | kuraw |

| A, A.5 | Dugwor | bek | səla | makar | məfaɗ | zlam | mukwa | tsela | tsaamakar | tseuɗ | kurow |

| A, A.5 | Zulgo-Gemzek | ilík | súla | màkər | əfáɗ | ə̀zləm | ndílík | təsəlá | tsàmàkə̀r | tswíɗ | kúrwá |

| A, A.5 | North Giziga | ɓlà | cêw | màːkàr | m̀fàɗ | ɮòm | mérkêɗ | tàːrnà | dàːɡàfàɗ | nɡòltêr | krô |

| A, A.5 | South Giziga | plá | cúw | máakə̀r | mə̀fáɗ | ɮúm | mérkéɗ | tàrnà | dàaŋɡàfáɗ (2 x 4) ? | nɡòltír | kúrú |

| A, A.5 | Mada | ftek | séla | mahkaɾ | wfaàë | zzlaèm | mokkoà | slaasélaà | slalahkaàr | oàboèlmboè | dzmoèkw |

| A, A.5 | Mafa | sə́táɗ | cew / cecew | makár | fáɗ | zlám | mokwa | tsáraɗ | tsamakaɗ | cœ́ɗ | kula |

| A, A.5 | Matal (1) | dì / tēkùlā | sɨ̄là | màkɨ̀r | ùfàɗ | ɨ̀ɮù | mùkʷā | mɨ̀ɗɨf | m̀tìɡìʃ | làdɨ̀ɡà | kùlù |

| A, A.5 | Matal (2) | dìì / tékùlá | sə̀là | mákə̀r | úfàɗ | ə́ɮùw | mə̀kwá | mə̀də̀f | mə̀tə̀ɡìʃ | ládə̀ɡá | kùlù |

| A, A.5 | Mbuko | kərtek | tsew | maakaŋ | fuɗo | ɗara | mbərka | tsuwɓe | dzəmaakaŋ | dəsuɗo | kuro |

| A, A.5 | Mefele | mə̀tá | cécèw | màhkár | fwàɗ | ɮàm | mòkwá | tsə̀làɗ | t͡ʃáhkàr | t͡ʃʉ́ɗ | dùmbók |

| A, A.5 | Merey | nə̀tê | súlò | màkàr | fàɗ | ɮàm | m̀kô | tàsə́là | tsàːmàːkàr | cö̂ɗ | krôw |

| A, A.5 | Mofu-Gudur | teɗ / ték (counting), pál (enumation) | t͡sew | máakar | məfaɗ | ɮam | maakwáw | maasála | daaŋɡafaɗ | ɮam-leték / ɮam-leteɗ | kúráw |

| A, A.5 | North Mofu | nettey | suho | makar | fáɗ | ɮàm | mukó | taasə́lá | tsamakàŋ | tsəɗ | kuro |

| A, A.5 | Moloko | bɪ̀lɛ́ŋ | tʃɛ́w | màkáɾ | ùfáɗ / mɔ̀fáɗ | ɮɔ̀m | mʊ̀kʷɔ̀ | ʃɪ̀sɛ́ɾɛ́ | ɬálákáɾ | hɔ́lɔ́mbɔ́ | kʷʊ̀ɾɔ́ |

| A, A.5 | Muyang | bílìŋ | tʃỳ | màhkə̄r | fāɗ | ɮàm | mʊ̀kʷū | ādə́skə̄lā | āɮáláxkə̄r | āmbʊ́lmbō | krū |

| A, A.5 | Ouldeme (Wuzlam) | ʃɛ̄lɛ́ŋ | brɛ̄tʃâw / tʃâw | mākár | mə̄fáɗ | ɮàm | mōkō | sə̄sə̄lā | fə̄rfáɗ | álɓìt | kōlō |

| A, A.5 | Vame (Pelasla) | ɓìlɛ́ | tʃâw | máŋɡàn | fúːɗàw | ɗáːrà | márkà | tʃíɓà | ʒíːrɛ̀ | táhkɛ̀ | dʒɛm |

| A, A.6 | Sukur (1) | kə̀lí | bák | ma̋ken | fwáɗ | ɮám | mʊ́kwà | máɗáf | tə̀kə̀z | míçí / míɬí | ʔwàn |

| A, A.6 | Sukur (2) | tá.í | bákʼ | máːkə̀n | fwáɗ | ɮám | mə́kkwà | máɗaf | tə́kkəz | məɬi | wàŋ |

| A, A.7 | Buwal | tɛ́ŋɡʷʊ̄lɛ̀ŋ | ɡ͡bɑ́k | mɑ̄xkɑ́t̚ | ŋ̀fɑ́t̚ | dzɑ̄ɓɑ́n | ŋ̀ʷkʷɑ́x | ŋ̀ʃɪ́lɛ́t̚ | dzɑ̄mɑ̄xkɑ̄t̚ (5 + 3) | dzɑ́fɑ́t̚ (5 + 4) | wɑ́m |

| A, A.7 | Daba | takan | səray | makaɗ | faɗ | jeɓin | koh | cesireɗ | cəfaɗcəfaɗ (4 + 4) | dərfatakan (10–1) | ɡuɓ təɓa təɓa |

| A, A.7 | Gavar | ŋ̀tɑ́t̚ | ɡ͡bɑ̀k | mɑ̄xkɑ̀t̚ | ŋ̀fɑ̄t̚ | dzɑ̄ɓə̄n | ŋ̀kʷɑ́x | ŋ̀ʃɪ́lít̚ | dzɑ̄mɑ̄xkɑ̄t̚ (5 + 3) | dzɑ́ŋfɑ́t̚ (5 + 4) | wɑ̄m |

| A, A.7 | Mbedam | ntɑɗ | bɑk | mɑxkɑɗ | mfɑɗ | dʒəɓɑn | ŋkwɑx | diʃliɗ | dʒɑmɑxkɑɗ (5 + 3) | tsɑfɑɗ (5 + 4) | wɑm |

| A, A.7 | Mina (Hina) | ǹtá | suloɗ | mahkaɗ | mfáɗ | dzəbuŋ | ǹkú | dìsùlùɗ | fáɗfáɗ (2 x 4) | varkanta | ɡə̀ɓ |

| A, A.8 | Bacama (Bachama) | hiɗò | k͡pe | ḿwɔ̀kun | fwət | tuf | tukwə̀ltaka (5 + 1) | tukòluk͡pe (5 + 2) | fwɔ̂fwət (2 x 4) | ɗɔ̀mbiɗò (10–1) | bə̌w |

| A, A.8 | Fali (Fali of Mucella) | tɛ̀n / ʔar̃mə | bek / buk | màxk(u) | fwəɗ | tuf | yiɗə̀w | mbùr̃fuŋ | tùɣus | mɪ̀ðɪŋ | ɡùm |

| A, A.8 | Gude | tèen / rûŋ | bə̀ráʔy | màkk | ǹfwáɗ | tə́f | kùwà | mə̀ɗə̀f | tə̀ɣə́s | ìllíŋ | puʔ |

| A, A.8 | Gudu (Gudo) | ǰə́ŋ | bœ̀k | māːkə́n | fwád | tùf | kwǎ | mīskàtā | fɔ̄rfwād (2 x 4) | žīɛ́tə́pə̀n | pú |

| A, A.8 | Jimi (Mwulyen) | híɗò / tɛ̂n | búk / bíkə̌ | mwàkɨ́n / maxkə́n | fwad / fwátʼ | túhf / tɯ́f | túkwàldèáká / bə̌rfǐŋ | túkwàlóʔpé / tɯ̀ʁɯ́s | fwáfwàɗ (2 x 4) / mìɮíɲ | táàmbíɗò / pó? | bù |

| A, A.8 | Nzanyi | hɪɗè | buk | mɨ̀dɨfəl | fwət | tuf | kwɔx | mɨ̀skatə̀ | fwəfwaɗè (2 x 4) | təmɓeɗè | pu |

| A, A.8 | Zizilivakan | lɪm | sul | màxku | fwəy | mùxtyup | ŋ̀kwaʔ | mbùrfìŋ | tə̀ɣìs | mɨ̀ðì | ɡumù |

| B, B.1, Buduma | Buduma (Yedina) | ɡə̀tté | kí | ɡàkə́nnə́ | híɡáy | híŋɟì | hə̀ràkkə́ | tùlwár | wósə́kə́ | hílíɡár | hákkán |

| B, B.1, Kotoko Proper, North | Afade | sə́rə̀jā | sɗā | ɡàrkə̀ | ɡàɗē | ʃìʃí | və̀nārkə̄ (2 x 3) | kàtùl | vìyāɗē (2 x 4) | dìʃẽ̄ | χkàn |

| B, B.1, Kotoko Proper, North | Mpade | pál | ɡāsì | ɡòkúrò | ɡāɗè | ʃénsī | ʃéskótē | túlùr < Kanuri | jìlìɡàɗè (2 x 4) | jìàtálà | kán |

| B, B.1, Kotoko Proper, South | Lagwan | sə́ɣdia, tkú | χsɗá | ɡǎχkər | ɡǎɗe | ʃēʃí | vɛnǎχkər / vɛnǎχəkər (2 x 3) | kátul | vɛɲáɗe (2 x 4) | diʔiʃén | χkan |

| B, B.2 | Mbara | kítáy, ɗów | mòk | ùhú | púɗú | íɬím | ɬírá | mìɡzàk / mùɡizàk | mìsílày / mùsílày | wáːŋá | dòːɡò / dòk |

| B, B.2 | Musgu | kítáy, ɗáw | súlú | hú | púɗú | ɬím | ɬàːrà | mìɡzàk / mùɡzàk | mìtwìs / mìtìs | tíklá | dòːɡò |

| C | Gidar | tákà | súlà | hókù | póɗò | ɬé | ɬré | bùhúl | dòdòpórò (2 x 4) ? | váyták (10–1) ? | kláù |

Proto Language

[edit]The phonology of Proto-Central Chadic consists of 31 consonants, three vowels and a morpheme-level palatalization prosody. The 3 vowel phonemes are /a/, /i/ and /ɨ/. The consonants are as follows: [7]

| Bilabial | Alveolar | Laminal | Velar | Labiovelar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ||||

| Stop | Voiceless | p | t | t͡s | k | kʷ |

| Voiced | (b) | d | d͡z | g | gʷ | |

| Implosive | ɓ | ɗ | ||||

| Prenasalized | ᵐb | ⁿd | ⁿd͡z | (ᵑg) | (ᵑgʷ) | |

| Fricative | Voiceless | ɬ | s | x | xʷ | |

| Voiced | v | ɮ | z | ɣ | ɣʷ | |

| Trill | r | |||||

| Approximant | j | w | ||||

For the reconstructions see

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Gravina, Richard. 2014. Proto-Central Chadic Lexicon. Webonary.

- ^ Gravina, R. (2014). The phonology of Proto-Central Chadic: the reconstruction of the phonology and lexicon of Proto-Central Chadic, and the linguistic history of the Central Chadic languages (Doctoral dissertation, LOT: Utrecht).

- ^ Languages are closer to each other than are those of the northern branch

- ^ Blench, 2006. The Afro-Asiatic Languages: Classification and Reference List (ms)

- ^ a b Blench, Roger (2019). An Atlas of Nigerian Languages (4th ed.). Cambridge: Kay Williamson Educational Foundation.

- ^ Chan, Eugene (2019). "The Afro-Asiatic Language Phylum". Numeral Systems of the World's Languages.

- ^ "Central Chadic Reconstructions » Phonology". Retrieved 2025-10-06.

References

[edit]- Central Chadic resources at africanlanguages.org

Biu–Mandara languages

View on GrokipediaOverview

Definition and Affiliation

The Biu–Mandara languages, also known as the Central Chadic languages, form a major branch of the Chadic subfamily within the Afroasiatic language family. This branch encompasses over 70 languages spoken primarily by various ethnic groups in West Africa, particularly in the border regions of Nigeria, Cameroon, and Chad.[8][9] The name "Biu–Mandara" originates from prominent geographical features associated with the languages' core areas: the Biu Plateau in northeastern Nigeria and the Mandara Mountains straddling the Nigeria-Cameroon border. These languages are distinguished from the other primary Chadic branches—West Chadic, East Chadic, and Masa—by their intermediate position in the family's internal classification and shared phonological and lexical innovations.[9][10] Collectively, the Biu–Mandara languages are estimated to have over 2 million speakers, a figure derived from survey data up to the early 2000s that requires revision due to population growth and linguistic shifts.[2]Historical Development

The recognition of the Biu–Mandara languages, also known as Central Chadic, as a distinct subgroup within the Chadic branch of the Afroasiatic family emerged in the early 20th century amid broader efforts to classify African languages. Diedrich Westermann's 1927 analysis of West Sudanic languages first highlighted Chadic tongues, including those later identified as Central Chadic, by noting their typological affinities with Hamitic (now Cushitic and other Afroasiatic branches) elements, though he grouped them provisionally under a Sudanic umbrella.[11] This laid initial groundwork for separating Chadic from Niger-Congo and Nilo-Saharan families. Joseph Greenberg's seminal 1950 study further advanced this by formally integrating all Chadic languages into Afroasiatic, designating an early "Central Chadic" cluster encompassing languages from the Biu, Mandara, and related areas, based on shared lexical and morphological traits like pronominal systems.[12] A pivotal development occurred in the 1970s with Paul Newman's refinements to Chadic classification. In his 1977 framework, Newman separated the Masa languages as a coordinate fourth branch of Chadic—alongside West, East, and Central—due to their divergent phonology and lexicon, such as unique implosive series and verb morphology.[13] This redefinition positioned the residual Central Chadic languages, spanning Nigeria, Cameroon, and Chad, as the Biu–Mandara group, emphasizing innovations like vowel prosodies and consonant palatalization that distinguished them from Masa. Newman's work built on Greenberg's subgroups, consolidating Biu–Mandara into three primary divisions (A, B, and C) while underscoring the need for deeper comparative reconstruction to resolve internal diversity.[14] Advancing reconstruction efforts, Richard Gravina's 2014 doctoral thesis provided the first systematic phonology of Proto-Central Chadic, positing an inventory of 31 consonants (including stops, fricatives, nasals, and liquids across labial, alveolar, laminal, velar, and labialized velar places) and a minimal vowel system of three phonemes (/a/, /i/, /ɨ/), with no phonemic length contrasts.[14] Notably, Gravina reconstructed palatalization prosody as a suprasegmental feature operating at the morpheme or word level, influencing vowel harmony (fronting) or consonant shifts (e.g., laminals like *ts to [tʃ]), a trait preserved variably across Biu–Mandara subgroups. This model, supported by comparative data from over 60 languages, highlighted areal contact effects around Lake Chad and the Mandara Mountains as shaping post-proto divergences.[15] Debates on the branch's status persist into the 2020s, informed by broader Afroasiatic comparisons that probe Chadic's retention of proto-Afroasiatic features like gender marking and verb derivation. Recent studies question the genetic unity of certain Biu–Mandara subgroups (e.g., Kotoko's ties to North vs. South Central Chadic), attributing similarities to substrate influences from Nilo-Saharan or admixtures during migrations, while affirming the core group's coherence through shared prosodies and lexicon.[16] These discussions, drawing on lexicostatistics and phonological modeling, continue to refine the historical trajectory without altering the established quadripartite Chadic structure.[17]Geographic Distribution

In Nigeria

In northern Nigeria, Biu–Mandara languages are concentrated in Borno, Adamawa, and Gombe States, encompassing the Lake Chad basin and the Biu Plateau region. Key languages in this area include Tera, spoken by the Tera ethnic group in areas such as Akko, Yamaltu/Deba, Funakaye Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Gombe State, and Bayo and Kwaya LGAs of Borno State; Jara, primarily in Borno State; and Bura (also known as Pabir), associated with the Biu Plateau. The Tera language, with its endonym Nyimatli referring to its speakers, exemplifies colonial exonyms imposed during British administration, contrasting with native self-designations like Terawa used by communities. These languages are linked to ethnic groups such as the Tera and Bura, whose socio-cultural practices, including farming and traditional governance, reinforce linguistic identity amid regional conflicts.[9][18][19][20] In northeastern Nigeria, particularly Adamawa State, Biu–Mandara languages appear in highland and lowland zones, with distinctions between elevated terrains like the Mambilla Plateau fringes and riverine lowlands. Languages such as Kamwe and Marghi are spoken here, with Kamwe prevalent in Michika and Madagali LGAs, and Marghi Central in areas around Gombi LGA and southern Borno borders. The Kamwe ethnic group, native to these highlands, uses their language in daily interactions, while Marghi speakers, part of the broader Margi ethnic community, maintain it alongside cultural traditions like weaving and ironworking. Post-colonial naming often retains English-derived terms (e.g., "Kamwe" from administrative records), differing from native forms that emphasize clan affiliations. Multilingualism is common in border zones near Cameroon, where speakers alternate between Biu–Mandara varieties and neighboring Chadic or Niger-Congo languages for trade and social ties.[21][22][9] Hausa, as the dominant lingua franca in northern Nigeria, profoundly influences Biu–Mandara language use, promoting bilingualism among speakers for education, commerce, and administration, which has led to lexical borrowing and code-switching in urbanizing areas. This Hausa dominance contributes to varying vitality levels; for instance, Tera and Kamwe remain stable with intergenerational transmission, but smaller varieties face pressure from language shift, as noted in surveys up to the early 2020s. Ethnic associations, such as the Tera and Marghi cultural unions, actively promote language preservation through community events and literacy programs to counter these impacts.[23][24][25]In Cameroon and Chad

In Cameroon, the Biu–Mandara languages are primarily concentrated in the Far North Region, especially within the Mandara Mountains, where they are spoken by communities in areas around Maroua and Mokolo.[2] Key examples include Mafa (endonym Mafaak) and Daba, which reflect the region's linguistic diversity tied to montagnard ethnic groups.[26] Mafa, a prominent language in this area, has over 100,000 speakers.[27] The mountainous terrain of the Mandara Mountains has significantly shaped these languages, fostering strong dialectal variation due to isolated villages and rugged landscapes that limit inter-community contact.[28] For instance, dialects of Mafa and related languages exhibit adaptations in phonology and vocabulary influenced by highland agriculture and terraced farming practices.[5] Additionally, speakers of Biu–Mandara languages frequently interact with Fulfulde-speaking Fulbe groups, who dominate regional trade and herding; Fulfulde serves as a lingua franca, leading to lexical borrowing and bilingualism in mixed settlements.[29] In Chad, Biu–Mandara languages have a sparser presence, mainly near the Chari River and Lake Chad basins in the west, with examples such as Kotoko and Musgu occurring along the Cameroon border.[2][1] These feature cross-border dialects shared with Nigerian and Cameroonian communities, reflecting historical migrations across the porous frontiers.[30] The lacustrine environment around Lake Chad influences vocabulary related to fishing and seasonal flooding, contrasting with the highland adaptations in Cameroon.[5] Recent shifts in the 2020s, particularly in border zones, include increased migration driven by conflict and climate pressures, contributing to language endangerment among smaller dialects; assessments highlight risks from urbanization and displacement affecting intergenerational transmission as of 2023–2025.[31] For example, some Biu–Mandara varieties in these areas face vitality challenges due to the dominance of French, Arabic, and Fulfulde in education and administration.[32]Classification

Newman (1977)

In his 1977 classification, Paul Newman divided the Biu–Mandara languages into three main subgroups—A, B, and C—encompassing more than 40 languages spoken primarily in northern Nigeria and northern Cameroon. This tripartite model was grounded in a systematic comparison of shared lexical items, such as basic vocabulary for body parts and natural phenomena, and regular sound changes, including consonant shifts like the development of labialized velars in certain environments. Newman's approach critiqued earlier classifications, such as Johannes Lukas's expansive "Mandara" or "Chadic" groupings from the 1930s and 1950s, which relied on limited data and overlooked key phonological correspondences that better delimited internal relationships.[33] Subgroup A includes Tera, Hona, and Ga’anda, among others.[33] Subgroup B consists of Mandara, Sukur, and Daba, which exhibit shared innovations in morphology and lexicon.[33] Subgroup C encompasses Biu, Margi, and Bura, set apart by certain phonological and lexical features, including numeral systems that show resemblances to those in West Chadic languages.[33] Newman's framework provided the foundational structure for understanding Biu–Mandara internal diversity, influencing later refinements by emphasizing evidence-based subgrouping over geographic proximity alone.[33]Blench (2006)

In 2006, Roger Blench proposed a revised classification of the Biu–Mandara languages, maintaining the three primary branches A, B, and C while providing finer subdivisions, particularly within A, to better reflect genetic diversity and historical contacts. This approach integrated comparative evidence with sociolinguistic data, estimating around 50 languages. Blench's work critiques aspects of Newman's subgroup C as potentially paraphyletic.[34] Biu–Mandara A, the largest, is subdivided into clusters such as Tera (A.1), Bura (A.2), Margi (A.3), Mandara/Wandala (A.4, including Mafa and Kamwe), and Bata/Gude (further subgroups). These show influences from neighboring groups and conservative retentions in core vocabulary. Biu–Mandara B includes Kotoko and Musgu, unified by lowland features and shared lexical items related to riverine environments. Biu–Mandara C comprises Gidar, distinguished by unique phonological traits and possible areal influences.Gravina (2014)

In 2014, Richard Gravina presented a refined classification of the Biu–Mandara languages within Central Chadic, building on prior lexical approaches by emphasizing phonological evidence from regular sound changes and cognate density to establish genetic unity. His model aligns broadly with Blench's (2006) framework but introduces finer distinctions, such as subgroup A1 and A2, alongside subgroup B and C, determined through comparative analysis of lexical cognates and shared innovations in consonant systems across 78 lects. As of 2023, Ethnologue lists approximately 80 Biu–Mandara languages.[3][14][35] Gravina's phonological reconstructions underpin this classification, positing a Proto-Central Chadic inventory with three underlying vowels (*i, *a, ɨ) and a consonant system featuring fricatives like *ɬ and *hʷ, where vowel harmony operates via prosodic features such as palatalization (e.g., realizations influenced by front-high harmony). Key innovations include consonant shifts, such as *k > /x/ in word-final positions in branches like Hdi and certain Mafa varieties, and *ɬ > ɮ in southern subgroups, which correlate with high cognate density (over 30% in core vocabulary) to delineate boundaries between A, B, and C. These reconstructions draw from data in 59 languages and dialects, enabling proto-forms like *pɨri 'butterfly' (reflected as pə́ripə̀rínə in Gude) to illustrate shared heritage. Subgroup A1 (e.g., Mafa, Daba) features vowel prosody; A2 (e.g., Margi, Higi) consonant prosody; B (e.g., Vame and Mbuko in Hurza) mixed prosody; C (e.g., Kotoko like Afade) lacks active palatalization.[14][15] A notable aspect of Gravina's work is the incorporation of lesser-known lects, such as Jilbe (integrated into subgroup B based on phonological matches like the retention of *ts > /s/ and vowel prosody alignments). This expands the dataset to encompass 78 lects total, providing a more comprehensive phylogeny for Biu–Mandara within Chadic.[14][35] Gravina's contributions extend beyond classification, including an online lexicon of over 200 reconstructed Proto-Central Chadic items with supporting reflexes, hosted at Webonary, which facilitates further comparative research. These efforts have implications for broader Chadic phylogeny, highlighting areal contacts (e.g., with East Chadic via borrowed terms) and supporting the unity of Central Chadic against West and East branches through consistent phonological trajectories.[15][36]Languages

Subgroups

The Biu–Mandara languages are classified into three main branches—A, B, and C—following Paul Newman's 1977 framework, with refinements by Roger Blench (2006) and Richard Gravina (2011). These divisions are based on shared phonological, morphological, and lexical features. Blench further subdivides into clusters such as Tera-Bidiya, Bura-Higi, Bata, and Mafa-Mandara, while Gravina proposes eight internal subgroups (A1–A8). The following outlines key languages within these groups, drawing from consensus classifications.[1][37][6] Newman's A branch (Blench's core Central Chadic clusters) includes:- Tera-Bidiya cluster: Tera, Bidiya, Jara, Hwana, Ga'anda, Nyimatli, primarily in northeastern Nigeria and western Chad. These show innovations like labialized consonants.[14]

- Bura-Higi cluster: Bura (including Pabir, Cibak), Higi (Kamwe with dialects Nkafa, Dakwa), Hona (Hwana), Margi (North, South, Central varieties). Spoken in Adamawa and Borno States, Nigeria, and northern Cameroon, featuring suffix-based plural marking like /-j/.[37]

- Mandara-Mafa cluster (Gravina A4–A6): Mafa (North/South varieties), Mandara, Sukur, Dghwede, Glavda, Gvoko, Podoko, Lamang (Zaladva, Ghudavan), Hdi. Located in the Mandara Mountains of Cameroon and Nigeria, with high mutual intelligibility and vowel harmony.[38]

- Bata cluster (Gravina A8): Bata, Bacama (Bwatye), Zizilivakan, Gude, Fali (Vin, Huli dialects), Mbade, Mbudum. Forming dialect continua across Nigeria-Cameroon borders, treated as a genetic unit due to gradual variation.[6]

- Biu–Mandara (A)

- Tera-Bidiya (Tera, Bidiya, Jara, Hwana, Ga'anda)

- Bura-Higi (Bura, Kamwe, Margi, Hona)

- Mandara-Mafa (Mafa, Mandara, Sukur, Dghwede, Lamang, Hdi)

- Bata (Bata, Gude, Fali, Bacama)

- Biu–Mandara (B)

- Kotoko, Musgu

- Biu–Mandara (C)

- Gidar

- Unclassified: Jilbe, Nzanyi

Major Languages and Speakers

Mafa, a key Southeastern language, is spoken by ~700,000 people (as of 2023) primarily in northern Cameroon, with robust vitality. This marks a significant increase from ~136,000 in 1963.[41][42] Tera, from the Northern subgroup, has ~200,000 speakers (as of 2023) mainly in northeastern Nigeria, though some urban communities shift to Hausa.[43][24] Kamwe, in the Central subgroup, is spoken by ~660,000 people (as of 2020) across Nigerian highlands and Cameroon, including Mbam-Nkam dialects.[25] Among smaller languages, Daba has ~24,000 speakers (as of 2019) in Cameroon and Nigeria and is stable, though facing contact pressures.[32][44] Bata has ~300,000 speakers (as of 2020) but requires updated surveys for precise vitality.[45] Speaker counts draw from Ethnologue's 26th edition (2023) and related sources, with many Biu–Mandara languages showing stable to vigorous vitality amid Hausa/Fulfulde influence.[46] Dialect clusters like Mandara include over 10 varieties across Cameroon and Nigeria, with close mutual intelligibility.[47]Linguistic Features

Phonology

The Biu–Mandara languages, also known as Central Chadic, exhibit a proto-phonological system reconstructed with 33 consonants and a three-vowel inventory, characterized by prosodic features such as palatalization that influence both consonants and vowels across daughter languages.[14] This system reflects shared traits among the approximately 70 languages spoken in northeastern Nigeria, northern Cameroon, and western Chad, with variations emerging in northern and southern branches due to prosody types and sound shifts.[14] The proto-consonant inventory includes 33 phonemes, encompassing voiceless and voiced plosives (p, t, k, kʷ, b, d, g, gʷ), implosives (ɓ, ɗ), fricatives (ɬ, s, h, hʷ, v, ɮ, z, ɣ, ɣʷ), nasals (m, n), prenasalized stops (ᵐb, ⁿd, ⁿdz, ᵑg, ᵑgʷ), a trill (r), glides (j, w), and glottal stops (ʔ, ʔʲ).[14] Glottal elements like ʔ and h (including labialized hʷ) are reconstructed as core features, while ejectives (e.g., tsʼ, sʼ, kʼ, ɬʼ) appear in descendant languages such as Malgbe but are not proto-level.[14] Common shifts include the development of labialized consonants beyond velars in southern branches, such as pʷ in Proto-Margi and Proto-Bata, often arising from prosodic innovations.[14] The vowel system is based on three underlying phonemes (*a, *i, ɨ), with ɨ being the most frequent (64% in roots) and no evidence of advanced tongue root (ATR) harmony at the proto level.[14] Prosodic palatalization, reconstructed for Proto-Central Chadic and affecting about 20% of roots, triggers fronting (e.g., a → [ɛ] in Moloko) or consonant palatalization (e.g., s → sʲ in Proto-Higi), while labialization causes back-rounding (e.g., a → [ɔ]).[14] Many languages surface 5–7 vowels through these prosodies, though southern branches often reduce to two-vowel systems (a, ɨ) with harmony-driven alternations.[14] Most Biu–Mandara languages are tonal, typically with two to four registers (high, low, mid, downstep) that distinguish lexical items and grammatical categories, accompanied by downdrift where high tones lower after low ones.[48] For instance, in Lamang (northern branch), verb roots like kàli (low-low, continuous aspect) contrast with kálì (high-high, durative), and high tone often marks focus or perfective aspects.[48] Tone reconstruction remains preliminary due to data limitations.[14] Phonological variations distinguish branches: northern languages (e.g., Proto-Higi, Ouldeme) feature consonant prosody with expanded palatalized and labialized series (e.g., tsʲ, sʲ), more fricatives like lateral ɬ and ɮ, and shifts such as r → l or kʷ → ɓ.[14] Southern branches (e.g., Mofu-Gudur, Proto-Musgum) emphasize vowel prosody with harmony effects, retain implosives (ɓ, ɗ) without clicks, and show innovations like ɬ → ɮ or broader labialization from velars.[14] These differences arise from areal contacts and internal developments post-proto stage.[14]Numeral Systems

The numeral systems in Biu–Mandara languages are predominantly decimal, reflecting a base-10 structure inherited from Proto-Chadic, though some languages incorporate quinary elements, particularly in forming numerals 6–9 as combinations involving "five." These systems feature lexical innovations alongside cognates traceable to proto-forms, such as shared roots for "three" (*makir) and "four" (*fwar/vat) across subgroups. Higher numerals are typically constructed through addition and multiplication, with occasional contact-induced resemblances to West Chadic languages like Hausa in northern varieties.[49] Basic numerals from 1 to 10 vary across subgroups but show systematic patterns. Note that numeral forms can vary across dialects and orthographies within each language. In the Tera subgroup, Tera employs forms like 1 dà, 2 rap, 3 kúnú, 4 vàt, 5 fàd, 6 njò, 7 mut, 8 míyasi, 9 mìlam, and 10 gwan, where 10 serves as the primary compounding base.[50] In the Bura–Margi subgroup, Margi uses 1 ntang, 2 suda, 3 makir, 4 nfwar, 5 ntufu, 6 nkwa, 7 murfa, 8 ncisu, 9 umdla, and 10 kuma, with evident cognates to Tera in numbers 3 and 4.[50] The Higi subgroup, represented by Kamwe, has 1 tan, 2 bak, 3 maxkan, 4 fwar, 5 ncifa, 6 kwa, 7 birfunga, 8 tikisa, 9 thi, and 10 gum, highlighting shared kwa for 6 with Margi.[50] In the Mafa–Mandara subgroup, forms diverge more, as seen in partial data for Mafa (1 sətáɗ, 2 cew, 3 makár, 4 fwar), retaining the makár/fwar cognates.[49] Higher numerals are formed via decimal compounds, often using "ten" as a multiplier or addend. In Margi, 20 is mətlkùmnyì ("two tens"), 30 is expressed as "three tens," and 11 as kùmáu à sər táŋ ("ten and one"), combining multiplication and addition; 100 is ghàrú and 1000 dúbú (the latter borrowed from Hausa).[51] Northern Biu–Mandara languages, such as those in the Mandara group, show parallels to Hausa in compound structures for teens and tens due to historical contact. Some systems extend beyond pure decimal, with quinary innovations where 6–9 are phrasal, e.g., in Mandara, 6 is "five plus one" (napaririem potsu kes "five and one"), 7 "five plus two," up to 9 "five plus four," blending bases before shifting to decimal multiples of 10.[52][49] Gender distinctions appear in some languages, where numerals agree in gender with the modified noun, akin to patterns in other Chadic branches; for instance, Kamwe exhibits feminine forms for certain numerals when counting feminine nouns. Vigesimal elements are rare but present in select varieties, with 20 functioning as a secondary head in compounding for larger numbers.[9] The following table compares basic numerals 1–10 in representative Biu–Mandara languages, illustrating cognates (e.g., makir/maxkan for 3) and divergences. Forms are selected from specific sources and may vary by dialect:| Language (Subgroup) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tera (Tera) | dà | rap | kúnú | vàt | fàd | njò | mut | míyasi | mìlam | gwan |

| Margi (Bura–Margi) | ntang | suda | makir | nfwar | ntufu | nkwa | murfa | ncisu | umdla | kuma |

| Kamwe (Higi) | tan | bak | maxkan | fwar | ncifa | kwa | birfunga | tikisa | thi | gum |

| Mandara (Mandara) | kes | luo | tour | voveit | paririem | (5+1) | (5+2) | (5+3) | (5+4) | sinangavour |