Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

Marginal product

View on Wikipedia

In economics and in particular neoclassical economics, the marginal product or marginal physical productivity of an input (factor of production) is the change in output resulting from employing one more unit of a particular input (for instance, the change in output when a firm's labor is increased from five to six units), assuming that the quantities of other inputs are kept constant.[1]

The marginal product of a given input can be expressed[2] as:

where is the change in the firm's use of the input (conventionally a one-unit change) and is the change in the quantity of output produced (resulting from the change in the input). Note that the quantity of the "product" is typically defined ignoring external costs and benefits.

If the output and the input are infinitely divisible, so the marginal "units" are infinitesimal, the marginal product is the mathematical derivative of the production function with respect to that input. Suppose a firm's output Y is given by the production function:

where K and L are inputs to production (say, capital and labor, respectively). Then the marginal product of capital (MPK) and marginal product of labor (MPL) are given by:

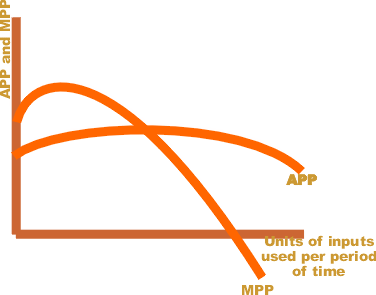

In the law of diminishing marginal returns, the marginal product initially increases when more of an input (say labor) is employed, keeping the other input (say capital) constant. Here, labor is the variable input and capital is the fixed input (in a hypothetical two-inputs model). As more and more of variable input (labor) is employed, marginal product starts to fall. Finally, after a certain point, the marginal product becomes negative, implying that the additional unit of labor has decreased the output, rather than increasing it. The reason behind this is the diminishing marginal productivity of labor.

The marginal product of labor is the slope of the total product curve, which is the production function plotted against labor usage for a fixed level of usage of the capital input.

In the neoclassical theory of competitive markets, the marginal product of labor equals the real wage. In aggregate models of perfect competition, in which a single good is produced and that good is used both in consumption and as a capital good, the marginal product of capital equals its rate of return. As was shown in the Cambridge capital controversy, this proposition about the marginal product of capital cannot generally be sustained in multi-commodity models in which capital and consumption goods are distinguished.[3]

Relationship of marginal product (MPP) with the total product (TPP)

[edit]The relationship can be explained in three phases- (1) Initially, as the quantity of variable input is increased, TPP rises at an increasing rate. In this phase, MPP also rises. (2) As more and more quantities of the variable inputs are employed, TPP increases at a diminishing rate. In this phase, MPP starts to fall. (3) When the TPP reaches its maximum, MPP is zero. Beyond this point, TPP starts to fall and MPP becomes negative.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brewer, Anthony (2010). The Making of the Classical Theory of Economic Growth. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415486200.

- ^ Mukherjee, Sampat; Mukherjee, Mallinath; Ghose, Amitava (2003). Microeconomics. New Delhi: Prentice-Hall of India. ISBN 81-203-2318-1.

- ^ Kurz, Heinz D. and Neri Salvadori (1995) Theory of Production: A Long-Period Analysis. Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Beck, Bernhard (2008). Volkswirtschaft verstehen. vdf, Hochsch.-Verlag an der ETH. ISBN 978-3-7281-3207-9.

- Rothbard, Murray N. (1995). Classical Economics: An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought, Volume II (PDF). Auburn, Alabama: Ludwig von Mises Institute. ISBN 0-945466-48-X.

Marginal product

View on GrokipediaDefinition and Formulation

Core Definition

The marginal product of an input, such as labor or capital, refers to the additional output produced by employing one more unit of that variable input while holding all other inputs constant.[1] This concept, often denoted in economic analysis as the marginal product of labor (MPL) or marginal product of capital (MPK), measures the incremental contribution of the extra input to total production in the short run, where at least one factor remains fixed.[5] The idea of marginal product traces its origins to classical economics in the 19th century, with significant development by American economist John Bates Clark in the late 1800s as part of the neoclassical revolution.[6] Clark's seminal work, The Distribution of Wealth (1899), formalized marginal productivity theory, arguing that factors of production receive remuneration equal to their marginal contributions to output under competitive conditions, building on earlier ideas from economists like John Stuart Mill.[7] This framework shifted economic thought from labor theories of value toward a productivity-based explanation of income distribution.[6] Marginal product typically focuses on the marginal physical product, which quantifies the physical increase in output units, distinct from the marginal revenue product that incorporates the monetary value of that output by multiplying the physical increment by the marginal revenue from selling additional units.[8] For instance, in agriculture, the marginal physical product of labor might manifest as the extra bushels of crops harvested when one additional worker is added to a fixed plot of land, assuming tools and weather remain unchanged.[9]Mathematical Formulation

The marginal product of an input, such as labor, measures the additional output produced by employing one more unit of that input, holding all other factors constant. In discrete terms, it is formulated as the ratio of the change in total product to the change in the input level:where TP denotes total product (output) and L represents the units of the variable input, such as labor. This formulation applies in scenarios where inputs are adjusted in whole units, common in empirical production analysis.[10] In continuous models, the marginal product is the derivative of the total product with respect to the input:

This captures the instantaneous rate of change in output as the input varies smoothly. For production processes modeled with multiple inputs, the marginal product of labor (MP_L) derives from the total production function Q = f(L, K), where K is fixed capital:

This partial derivative assumes ceteris paribus conditions, with other inputs held constant to isolate the effect of the variable input. The short-run context typically features one variable input, such as labor, while capital remains fixed, reflecting real-world constraints like plant capacity.[11][12] To illustrate the discrete formula, consider a firm where total output increases from 100 units to 115 units upon hiring one additional worker, raising labor from 5 to 6 units; the marginal product is then (115 - 100) / (6 - 5) = 15 units per worker. This calculation highlights how marginal product quantifies incremental productivity contributions under fixed other factors.[10]