Recent from talks

Nothing was collected or created yet.

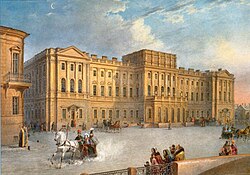

Mariinsky Palace

View on WikipediaMariinsky Palace (Russian: Мариинский дворец, romanized: Mariinskij dvorec), also known as Marie Palace, was the last neoclassical Imperial residence to be constructed in Saint Petersburg. It was built between 1839 and 1844, designed by the court architect Andrei Stackenschneider. It houses the city's Legislative Assembly.

Key Information

Location

[edit]

The palace stands on the south side of Saint Isaac's Square, just across the Blue Bridge from Saint Isaac's Cathedral. The site had been previously owned by Zakhar Chernyshev, and contained his home designed by Jean-Baptiste Vallin, which was built between 1762 and 1768. Chernyshev occasionally lent his home to foreign dignitaries visiting the capital, such as Louis Henri, Prince of Condé.

From 1825 to 1839, the Chernyshev Palace, as it was then known, was the site of the Nicholas Cavalry College, where Mikhail Lermontov was known to have studied for two years. The palace was demolished in 1839, and materials were reused in the construction of the Mariinsky Palace.

Conception and style

[edit]

The palace was conceived by Nicholas I as a present to his eldest daughter, Grand Duchess Maria Nikolaevna, on the occasion of her marriage to Maximilian de Beauharnais, Empress Joséphine's grandson.

Although the reddish-brown facade is elaborately rusticated and features corinthian columns arranged in a traditional Neoclassical mode, the whole design was inspired by the 17th-century French Baroque messuages. Other eclectic influences are visible in the Renaissance details of exterior ornamentation, and the interior decoration, with each room designed in a different historic style. The palace is now painted white.

State Council

[edit]The Mariinsky Palace returned to Imperial ownership in 1884, where it remained until 1917. During that period, the palace housed the State Council, Imperial Chancellery, and Committee of Ministers, which after 1905 became the Council of Ministers. The grand hall for the sessions of the State Council was designed by Leon Benois.

On April 15, 1902, Socialist Revolutionary Party member Stepan Balmashov assassinated the Minister of Internal Affairs, Dmitry Sipyagin, while the minister was between meetings at the palace.

In 1904, painter Ilya Repin completed Ceremonial Sitting of the State Council on 7 May 1901. The painting was commissioned as a commemoration of the State Council's centenary. The canvas is 4 by 8.77 metres (13.1 ft × 28.8 ft), and features 81 historical figures, including Nicholas II. Repin recorded in his journal the painting was on display at the Winter Palace for some time before its installation at Mariinsky Palace.

Government use

[edit]The Russian Provisional Government took full possession of the palace in March 1917, and gave it over to the Provisional Council soon after. Following the October Revolution, the palace housed various Soviet ministries and academies. During the war with Germany, the palace was converted to a hospital, and was subject to intense bombing.

After the war, the palace became the residence of the Petrograd Soviet. During the 1991 coup attempt, the Emergency Committee used the palace as a base of operations. Barricades and heavy fortifications were constructed along the palace's perimeter, which remained for some time after the coup was suppressed.

The palace has been the site of the Legislative Assembly of Saint Petersburg since 1994.

References

[edit]- Belyakova Z.I. Mariinsky dvorets. SPb, 1996.

- Petrov G.F. Dvorets u Sinego mosta: Mariinsky dvorets v Sankt-Petersburge. SPb, 2001.