Recent from talks

Contribute something

Nothing was collected or created yet.

October Revolution

View on Wikipedia

| October Revolution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Russian Revolution and the revolutions of 1917–1923 | |||||||

The Winter Palace of Petrograd, one day after the insurrection, 8 November | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Few Red Guard soldiers wounded[3] | All imprisoned or deserted | ||||||

The October Revolution,[b] also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution[c] (in Soviet historiography), October coup,[4][5] Bolshevik coup,[5] or Bolshevik revolution,[6][7] was the second of two revolutions in Russia in 1917. It was led by Vladimir Lenin's Bolsheviks as part of the broader Russian Revolution of 1917–1923. It began through an insurrection in Petrograd (now Saint Petersburg) on 7 November 1917 [O.S. 25 October]. It was the precipitating event of the Russian Civil War. The initial stage of the October Revolution, which involved the assault on Petrograd, occurred largely without any casualties.[8][9][10]

The October Revolution followed and capitalised on the February Revolution earlier that year, which had led to the abdication of Nicholas II and the creation of the Russian Provisional Government. The provisional government, led by Alexander Kerensky, had taken power after Grand Duke Michael, the younger brother of Nicholas II, declined to take power. During this time, urban workers began to organize into councils (soviets) wherein revolutionaries criticized the provisional government and its actions. The provisional government remained unpopular, especially because it was continuing to fight in World War I, and had ruled with an iron fist throughout mid-1917 (including killing hundreds of protesters in the July Days). It declared the Russian Republic on 1 [N.S. 14] September 1917.

The situation grew critical in late 1917 as the Directorate, led by the left-wing Party of Socialist-Revolutionaries (SRs), controlled the government. The far-left Bolsheviks were deeply unhappy with the government, and began spreading calls for a military uprising. On 10 [N.S. 23] October 1917, the Petrograd Soviet, led by Leon Trotsky, voted to back a military uprising. On 24 October [N.S. 6 November], the government closed numerous newspapers and closed Petrograd, attempting to forestall the revolution; minor armed skirmishes ensued. The next day, a full-scale uprising erupted as a fleet of Bolshevik sailors entered the harbor and tens of thousands of soldiers rose up in support of the Bolsheviks. Bolshevik Red Guards under the Military-Revolutionary Committee began to occupy government buildings. In the early morning of 26 October [N.S. 8 November], they captured the Winter Palace — the seat of the Provisional government located in Petrograd, then capital of Russia.

As the revolution was not universally recognized, the country descended into civil war, which lasted until late 1922 and led to the creation of the Soviet Union. The historiography of the event has varied. The victorious Soviet Union viewed it as a validation of its ideology and the triumph of the working class over capitalism. On the other hand, the western allies later intervened against the Bolsheviks in the civil war. The Revolution inspired many cultural works and ignited communist movements globally. October Revolution Day was a public holiday in the Soviet Union, marking its key role in the state's founding, and many communist parties around the world still celebrate it.

Etymology

[edit]Despite occurring in November of the Gregorian calendar, the event is most commonly known as the "October Revolution" (Октябрьская революция) because at the time Russia still used the Julian calendar. The event is sometimes known as the "November Revolution", after the Soviet Union modernized its calendar.[11][12][13] To avoid confusion, both O.S. and N.S. dates have been given for events. For more details see Old Style and New Style dates. It was sometimes known as the Bolshevik Revolution, or the Communist Revolution.[14]

Initially the event was referred to as the "October coup" (Октябрьский переворот) or the "Uprising of the 3rd", as seen in contemporary documents, for example in the first editions of Lenin's complete works.[citation needed]

Background

[edit]February Revolution

[edit]The February Revolution had toppled Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and replaced his government with the Russian Provisional Government. However, the provisional government was weak and riven by internal dissension. It continued to wage World War I, which became increasingly unpopular. There was a nationwide crisis affecting social, economic, and political relations. Disorder in industry and transport had intensified, and difficulties in obtaining provisions had increased. Gross industrial production in 1917 decreased by over 36% of what it had been in 1914. In the autumn, as much as 50% of all enterprises in the Urals, the Donbas, and other industrial centers were closed down, leading to mass unemployment. At the same time, the cost of living increased sharply. Real wages fell to about 50% of what they had been in 1913. By October 1917, Russia's national debt had risen to 50 billion roubles. Of this, debts to foreign governments constituted more than 11 billion roubles. The country faced the threat of financial bankruptcy.

German support

[edit]Vladimir Lenin, who had been living in exile in Switzerland, with other dissidents organized a plan to negotiate a passage for them through Germany, with whom Russia was then at war. Recognizing that these dissidents could cause problems for their Russian enemies, the German government agreed to permit 32 Russian citizens, among them Lenin and his wife, to travel in a sealed train carriage through their territory.

Upon his arrival in Petrograd on 3 April 1917, Lenin issued his April Theses that called on the Bolsheviks to take over the Provisional Government, usurp power, and end the war.

Unrest by workers, peasants, and soldiers

[edit]Throughout June, July, and August 1917, it was common to hear working-class Russians speak about their lack of confidence in the Provisional Government. Factory workers around Russia felt unhappy with the growing shortages of food, supplies, and other materials. They blamed their managers or foremen and would even attack them in the factories. The workers blamed many rich and influential individuals for the overall shortage of food and poor living conditions. Workers saw these rich and powerful individuals as opponents of the Revolution and called them "bourgeois", "capitalist", and "imperialist".[15]

In September and October 1917, there were mass strike actions by the Moscow and Petrograd workers, miners in the Donbas, metalworkers in the Urals, oil workers in Baku, textile workers in the Central Industrial Region, and railroad workers on 44 railway lines. In these months alone, more than a million workers took part in strikes. Workers established control over production and distribution in many factories and plants in a social revolution.[16] Workers organized these strikes through factory committees. The factory committees represented the workers and were able to negotiate better working conditions, pay, and hours. Even though workplace conditions may have been increasing in quality, the overall quality of life for workers was not improving. There were still shortages of food and the increased wages workers had obtained did little to provide for their families.[15]

By October 1917, peasant uprisings were common. By autumn, the peasant movement against the landowners had spread to 482 of 624 counties, or 77% of the country. As 1917 progressed, the peasantry increasingly began to lose faith that the land would be distributed to them by the Social Revolutionaries and the Mensheviks. Refusing to continue living as before, they increasingly took measures into their own hands, as can be seen by the increase in the number and militancy of the peasant's actions. Over 42% of all the cases of destruction (usually burning down and seizing property from the landlord's estate) recorded between February and October occurred in October.[17] While the uprisings varied in severity, complete uprisings and seizures of the land were not uncommon. Less robust forms of protest included marches on landowner manors and government offices, as well as withholding and storing grains rather than selling them.[18] When the Provisional Government sent punitive detachments, it only enraged the peasants. In September, the garrisons in Petrograd, Moscow, and other cities, the Northern and Western fronts, and the sailors of the Baltic Fleet declared through their elected representative body Tsentrobalt that they did not recognize the authority of the Provisional Government and would not carry out any of its commands.[19]

Soldiers' wives were key players in the unrest in the villages. From 1914 to 1917, almost 50% of healthy men were sent to war, and many were killed on the front, resulting in many females being head of the household. Often—when government allowances were late and were not sufficient to match the rising costs of goods—soldiers' wives sent masses of appeals to the government, which went largely unanswered. Frustration resulted, and these women were influential in inciting "subsistence riots"—also referred to as "hunger riots", "pogroms", or "baba riots". In these riots, citizens seized food and resources from shop owners, who they believed to be charging unfair prices. Upon police intervention, protesters responded with "rakes, sticks, rocks, and fists."[20]

Antiwar demonstrations

[edit]In a diplomatic note of 1 May, the minister of foreign affairs, Pavel Milyukov, expressed the Provisional Government's desire to continue the war against the Central Powers "to a victorious conclusion", arousing broad indignation. On 1–4 May, about 100,000 workers and soldiers of Petrograd, and, after them, the workers and soldiers of other cities, led by the Bolsheviks, demonstrated under banners reading "Down with the war!" and "All power to the soviets!" The mass demonstrations resulted in a crisis for the Provisional Government.[21] 1 July saw more demonstrations, as about 500,000 workers and soldiers in Petrograd demonstrated, again demanding "all power to the soviets," "down with the war," and "down with the ten capitalist ministers." The Provisional Government opened an offensive against the Central Powers on 1 July, which soon collapsed. The news of the offensive's failure intensified the struggle of the workers and the soldiers.

July days

[edit]

On 16 July, spontaneous demonstrations of workers and soldiers began in Petrograd, demanding that power be turned over to the soviets. The Central Committee of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party provided leadership to the spontaneous movements. On 17 July, over 500,000 people participated in what was intended to be a peaceful demonstration in Petrograd, the so-called July Days. The Provisional Government, with the support of Socialist-Revolutionary Party-Menshevik leaders of the All-Russian Executive Committee of the Soviets, ordered an armed attack against the demonstrators, killing hundreds.[22]

A period of repression followed. On 5–6 July, attacks were made on the editorial offices and printing presses of Pravda and on the Palace of Kshesinskaya, where the Central Committee and the Petrograd Committee of the Bolsheviks were located. On 7 July, the government ordered the arrest and trial of Vladimir Lenin, who was forced to go underground, as he had done under the Tsarist regime. Bolsheviks were arrested, workers were disarmed, and revolutionary military units in Petrograd were disbanded or sent to the war front. On 12 July, the Provisional Government published a law introducing the death penalty at the front. The second coalition government was formed on 24 July, chaired by Alexander Kerensky and consisted mostly of Socialists.[23] Kerensky's government introduced a number of liberal rights, such as freedom of speech, equality before the law, and the right to form unions and arrange labor strikes.[citation needed]

In response to a Bolshevik appeal, Moscow's working class began a protest strike of 400,000 workers. They were supported by strikes and protest rallies by workers in Kiev, Kharkov, Nizhny Novgorod, Ekaterinburg, and other cities.

Kornilov affair

[edit]In what became known as the Kornilov affair, General Lavr Kornilov, who had been Commander-in-Chief since 18 July, with Kerensky's agreement directed an army under Aleksandr Krymov to march toward Petrograd to restore order.[24] According to some accounts, Kerensky appeared to become frightened by the possibility that the army would stage a coup, and reversed the order. By contrast, historian Richard Pipes has argued that the episode was engineered by Kerensky.[25] On 27 August, feeling betrayed by the government, Kornilov pushed on towards Petrograd. With few troops to spare at the front, Kerensky turned to the Petrograd Soviet for help. Bolsheviks, Mensheviks, and Socialist Revolutionaries confronted the army and convinced them to stand down.[26] The Bolsheviks' influence over railroad and telegraph workers also proved vital in stopping the movement of troops. The political right felt betrayed, and the left was resurgent. The first direct consequence of Kornilov's failed coup was the formal abolition of the monarchy and the proclamation of the Russian Republic on 1 September.[27]

With Kornilov defeated, the Bolsheviks' popularity in the soviets grew significantly, both in the central and local areas. On 31 August, the Petrograd Soviet of Workers and Soldiers Deputies—and, on 5 September, the Moscow Soviet Workers Deputies—adopted the Bolshevik resolutions on the question of power. The Bolsheviks were able to take over in Briansk, Samara, Saratov, Tsaritsyn, Minsk, Kiev, Tashkent, and other cities.[citation needed]

Revolution

[edit]Planning

[edit]

On 10 October 1917 (O.S.; 23 October, N.S.), the Bolsheviks' Central Committee voted 10–2 for a resolution saying that "an armed uprising is inevitable, and that the time for it is fully ripe."[28] At the Committee meeting, Lenin discussed how the people of Russia had waited long enough for "an armed uprising," and it was the Bolsheviks' time to take power. Lenin expressed his confidence in the success of the planned insurrection. His confidence stemmed from months of Bolshevik buildup of power and successful elections to different committees and councils in major cities such as Petrograd and Moscow.[29] Membership of the Bolshevik party had risen from 24,000 members in February 1917 to 200,000 members by September 1917.[30]

The Bolsheviks created a revolutionary military committee within the Petrograd soviet, led by the Soviet's president, Leon Trotsky. The committee included armed workers, sailors, and soldiers, and assured the support or neutrality of the capital's garrison. The committee methodically planned to occupy strategic locations through the city, almost without concealing their preparations: the Provisional Government's President Kerensky was himself aware of them; and some details, leaked by Lev Kamenev and Grigory Zinoviev, were published in newspapers.[31][32]

Onset

[edit]In the early morning of 24 October (O.S.; 6 November N.S.), a group of soldiers loyal to Kerensky's government marched on the printing house of the Bolshevik newspaper, Rabochiy put (Worker's Path), seizing and destroying printing equipment and thousands of newspapers. Shortly thereafter, the government announced the immediate closure of not only Rabochiy put but also the left-wing Soldat, as well as the far-right newspapers Zhivoe slovo and Novaia Rus. The editors and contributors of these newspapers were seen to be calling for insurrection and were to be prosecuted on criminal charges.[33]

In response, at 9 a.m. the Bolshevik Military Revolutionary Committee issued a statement denouncing the government's actions. At 10 a.m., Bolshevik-aligned soldiers successfully retook the Rabochiy put printing house. Kerensky responded at approximately 3 p.m. that afternoon by ordering the raising of all but one of Petrograd's bridges, a tactic used by the government several months earlier during the July Days. What followed was a series of sporadic clashes over control of the bridges, between Red Guard militias aligned with the Military-Revolutionary Committee and military units still loyal to the government. At approximately 5 p.m. the Military-Revolutionary Committee seized the Central Telegraph of Petrograd, giving the Bolsheviks control over communications through the city.[33][34]

On 25 October (O.S.; 7 November, N.S.) 1917, the Bolsheviks led their forces in the uprising in Petrograd (now St. Petersburg, then capital of Russia) against the Provisional Government. The event coincided with the arrival of a pro-Bolshevik flotilla—consisting primarily of five destroyers and their crews, as well as marines—in Petrograd harbor. At Kronstadt, sailors announced their allegiance to the Bolshevik insurrection. In the early morning, from its heavily guarded and picketed headquarters in Smolny Palace, the Military-Revolutionary Committee designated the last of the locations to be assaulted or seized. The Red Guards systematically captured major government facilities, key communication installations, and vantage points with little opposition. The Petrograd Garrison and most of the city's military units joined the insurrection against the Provisional Government.[32] The insurrection was timed and organized to hand state power to the Second All-Russian Congress of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, which began on this day.

After the majority of the petrograd Soviet passed into the hands of the Bolsheviks, [Trotsky] was elected its chairman and in that position organized and led the insurrection of October 25.

Kerensky and the Provisional Government were virtually helpless to offer significant resistance. Railways and railway stations had been controlled by Soviet workers and soldiers for days, making rail travel to and from Petrograd impossible for Provisional Government officials. The Provisional Government was also unable to locate any serviceable vehicles. On the morning of the insurrection, Kerensky desperately searched for a means of reaching military forces he hoped would be friendly to the Provisional Government outside the city and ultimately borrowed a Renault car from the American embassy, which he drove from the Winter Palace, along with a Pierce Arrow. Kerensky was able to evade the pickets going up around the palace and to drive to meet approaching soldiers.[33]

As Kerensky left Petrograd, Lenin wrote a proclamation To the Citizens of Russia, stating that the Provisional Government had been overthrown by the Military-Revolutionary Committee. The proclamation was sent by telegraph throughout Russia, even as the pro-Soviet soldiers were seizing important control centers throughout the city. One of Lenin's intentions was to present members of the Soviet congress, who would assemble that afternoon, with a fait accompli and thus forestall further debate on the wisdom or legitimacy of taking power.[33]

Assault on the Winter Palace

[edit]A final assault against the Winter Palace—against 3,000 cadets, officers, cossacks, and female soldiers—was not vigorously resisted.[33][36] The Bolsheviks delayed the assault because they could not find functioning artillery.[37] At 6:15 p.m., a large group of artillery cadets abandoned the palace, taking their artillery with them. At 8:00 p.m., 200 cossacks left the palace and returned to their barracks.[33]

While the cabinet of the provisional government within the palace debated what action to take, the Bolsheviks issued an ultimatum to surrender. Workers and soldiers occupied the last of the telegraph stations, cutting off the cabinet's communications with loyal military forces outside the city. As the night progressed, crowds of insurgents surrounded the palace, and many infiltrated it.[33] At 9:45 p.m, the cruiser Aurora fired a blank shot from the harbor. Some of the revolutionaries entered the palace at 10:25 p.m. and there was a mass entry 3 hours later.

By 2:10 a.m. on 26 October, Bolshevik forces had gained control. The cadets and the 140 volunteers of the Women's Battalion surrendered rather than resist the 40,000 strong attacking force.[38][39] After sporadic gunfire throughout the building, the cabinet of the Provisional Government surrendered, and were imprisoned in Peter and Paul Fortress. The only member who was not arrested was Kerensky himself, who had already left the palace.[33][40]

With the Petrograd Soviet now in control of government, garrison, and proletariat, the Second All Russian Congress of Soviets held its opening session on the day, while Trotsky dismissed the opposing Mensheviks and the Socialist Revolutionaries (SR) from Congress.

Dybenko's disputed role

[edit]Some sources contend that as the leader of Tsentrobalt, Pavlo Dybenko played a crucial role in the revolt and that the ten warships that arrived at the city with ten thousand Baltic Fleet mariners were the force that took the power in Petrograd and put down the Provisional Government. The same mariners then dispersed by force the elected parliament of Russia,[41] and used machine-gun fire against demonstrators in Petrograd,[citation needed] killing about 100 demonstrators and wounding several hundred.[citation needed] Dybenko in his memoirs mentioned this event as "several shots in the air". These are disputed by various sources, such as Louise Bryant,[42] who claims that news outlets in the West at the time reported that the unfortunate loss of life occurred in Moscow, not Petrograd, and the number was much less than suggested above. As for the "several shots in the air", there is little evidence suggesting otherwise.

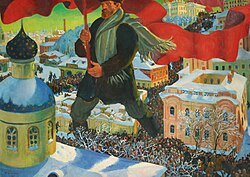

Later Soviet portrayal

[edit]While the seizure of the Winter Palace happened almost without resistance, Soviet historians and officials later tended to depict the event in dramatic and heroic terms.[32][43][44] The historical reenactment titled The Storming of the Winter Palace was staged in 1920. This reenactment, watched by 100,000 spectators, provided the model for official films made later, which showed fierce fighting during the storming of the Winter Palace,[45] although, in reality, the Bolshevik insurgents had faced little opposition.[36]

Later accounts of the heroic "storming of the Winter Palace" and "defense of the Winter Palace" were propaganda by Bolshevik publicists. Grandiose paintings depicting the "Women's Battalion" and photo stills taken from Sergei Eisenstein's staged film depicting the "politically correct" version of the October events in Petrograd came to be taken as truth.[46]

Historical falsification of political events such as the October Revolution and the Brest-Litovsk Treaty became a distinctive element of Stalin's regime. A notable example is the 1938 publication, History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (Bolsheviks),[47] in which the history of the governing party was significantly altered and revised including the importance of the leading figures during the Bolshevik revolution. Retrospectively, Lenin's primary associates such as Zinoviev, Trotsky, Radek and Bukharin were presented as "vacillating", "opportunists" and "foreign spies" whereas Stalin was depicted as the chief discipline during the revolution. However, in reality, Stalin was considered a relatively unknown figure with secondary importance at the time of the event.[48]

In his book, The Stalin School of Falsification, Leon Trotsky argued that the Stalinist faction routinely distorted historical events and the importance of Bolshevik figures especially during the October Revolution. He cited a range of historical documents such as private letters, telegrams, party speeches, meeting minutes, and suppressed texts such as Lenin's Testament.[49]

Outcome

[edit]

New government established

[edit]Lenin initially turned down the leading position of Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars when the Bolsheviks formed a new government, after the October Revolution in 1917, and suggested Trotsky for the position. However, Trotsky refused the position and other Bolsheviks insisted that Lenin assume principal responsibility which resulted in Lenin eventually accepting the role of chairman.[51][52][53]

The Second Congress of Soviets consisted of 670 elected delegates: 300 were Bolsheviks and nearly 100 were Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, who also supported the overthrow of the Alexander Kerensky government.[54] When the fall of the Winter Palace was announced, the Congress adopted a decree transferring power to the Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies, thus ratifying the Revolution.

The transfer of power was not without disagreement. The center and right wings of the Socialist Revolutionaries, as well as the Mensheviks, believed that Lenin and the Bolsheviks had illegally seized power and they walked out before the resolution was passed. As they exited, they were taunted by Trotsky who told them "You are pitiful isolated individuals; you are bankrupts; your role is played out. Go where you belong from now on—into the dustbin of history!"[55]

The following day, 26 October, the Congress elected a new cabinet of Bolsheviks, pending the convocation of a Constituent Assembly. This new Soviet government was known as the council (Soviet) of People's Commissars (Sovnarkom), with Lenin as a leader. Lenin allegedly approved of the name, reporting that it "smells of revolution".[56] The cabinet quickly passed the Decree on Peace and the Decree on Land. This new government was also officially called "provisional" until the Assembly was dissolved.

Anti-Bolshevik sentiment

[edit]That same day, posters were pinned on walls and fences by the Socialist Revolutionaries, describing the takeover as a "crime against the motherland" and "revolution"; this signaled the next wave of anti-Bolshevik sentiment. The next day, the Mensheviks seized power in Georgia and declared it an independent republic; the Don Cossacks also claimed control of their government. The Bolshevik strongholds were in the cities, particularly Petrograd, with support much more mixed in rural areas. The peasant-dominated Left SR party was in coalition with the Bolsheviks. There were reports that the Provisional Government had not conceded defeat and were meeting with the army at the Front.

Anti-Bolshevik sentiment continued to grow as posters and newspapers started criticizing the actions of the Bolsheviks and repudiated their authority. The executive committee of Peasants Soviets "[refuted] with indignation all participation of the organized peasantry in this criminal violation of the will of the working class".[57] This eventually developed into major counter-revolutionary action, as on 30 October (O.S., 12 November, N.S.) when Cossacks, welcomed by church bells, entered Tsarskoye Selo on the outskirts of Petrograd with Kerensky riding on a white horse. Kerensky gave an ultimatum to the rifle garrison to lay down weapons, which was promptly refused. They were then fired upon by Kerensky's Cossacks, which resulted in 8 deaths. This turned soldiers in Petrograd against Kerensky as being the Tsarist regime. Kerensky's failure to assume authority over troops was described by John Reed as a "fatal blunder" that signaled the final end of his government.[58] Over the following days, the battle against the anti-Bolsheviks continued. The Red Guard fought against Cossacks at Tsarskoye Selo, with the Cossacks breaking rank and fleeing, leaving their artillery behind. On 31 October 1917 (13 November, N.S.), the Bolsheviks gained control of Moscow after a week of bitter street-fighting. Artillery had been freely used, with an estimated 700 casualties. However, there was continued support for Kerensky in some of the provinces.

After the fall of Moscow, there was only minor public anti-Bolshevik sentiment, such as the newspaper Novaya Zhizn, which criticized the Bolsheviks' lack of manpower and organization in running their party, let alone a government. Lenin confidently claimed that there is "not a shadow of hesitation in the masses of Petrograd, Moscow and the rest of Russia" in accepting Bolshevik rule.[59]

Governmental reforms

[edit]On 10 November 1917 (23 November, N.S.), the government applied the term "citizens of the Russian Republic" to Russians, whom they sought to make equal in all possible respects, by the nullification of all "legal designations of civil inequality, such as estates, titles, and ranks."[60]

The long-awaited Constituent Assembly elections were held on 12 November (O.S., 25 November, N.S.) 1917. In contrast to their majority in the Soviets, the Bolsheviks only won 175 seats in the 715-seat legislative body, coming in second behind the Socialist Revolutionary Party, which won 370 seats, although the SR Party no longer existed as a whole party by that time, as the Left SRs had gone into coalition with the Bolsheviks from October 1917 to March 1918 (a cause of dispute of the legitimacy of the returned seating of the Constituent Assembly, as the old lists, were drawn up by the old SR Party leadership, and thus represented mostly Right SRs, whereas the peasant soviet deputies had returned majorities for the pro-Bolshevik Left SRs). The Constituent Assembly was to first meet on 28 November (O.S.) 1917, but its convocation was delayed until 5 January (O.S.; 18 January, N.S.) 1918 by the Bolsheviks. On its first and only day in session, the Constituent Assembly came into conflict with the Soviets, and it rejected Soviet decrees on peace and land, resulting in the Constituent Assembly being dissolved the next day by order of the Congress of Soviets.[61]

On 16 December 1917 (29 December, N.S.), the government ventured to eliminate hierarchy in the army, removing all titles, ranks, and uniform decorations. The tradition of saluting was also eliminated.[60]

On 20 December 1917 (2 January 1918, N.S.), the Cheka was created by Lenin's decree.[62] These were the beginnings of the Bolsheviks' consolidation of power over their political opponents. The Red Terror began in September 1918, following a failed assassination attempt on Lenin. The French Jacobin Terror was an example for the Soviet Bolsheviks. Trotsky had compared Lenin to Maximilien Robespierre as early as 1904, when Trotsky was a critic of Lenin and his political opponent within the Marxist movement.[63] In his book, Terrorism and Communism: A Reply to Karl Kautsky, Trotsky argued that the reign of terror began with the White Terror under the White Guard forces and the Bolsheviks responded with the Red Terror.[64]

The Decree on Land ratified the actions of the peasants who throughout Russia had taken private land and redistributed it among themselves. The Bolsheviks viewed themselves as representing an alliance of workers and peasants signified by the Hammer and Sickle on the flag and the coat of arms of the Soviet Union. Other decrees:

- All private property was nationalized by the government.

- All Russian banks were nationalized.

- Private bank accounts were expropriated.

- The properties of the Russian Orthodox Church (including bank accounts) were expropriated.

- All foreign debts were repudiated.

- Control of the factories was given to the soviets.

- Wages were fixed at higher rates than during the war, and a shorter, eight-hour working day was introduced.

Timeline of the spread of Soviet power (Gregorian calendar dates)

[edit]- 5 November 1917: Tallinn.

- 7 November 1917: Petrograd, Minsk, Novgorod, Ivanovo-Voznesensk and Tartu

- 8 November 1917: Ufa, Kazan, Yekaterinburg, and Narva; (failed in Kiev)

- 9 November 1917: Vitebsk, Yaroslavl, Saratov, Samara, and Izhevsk

- 10 November 1917: Rostov, Tver, and Nizhny Novgorod

- 12 November 1917: Voronezh, Smolensk, and Gomel

- 13 November 1917: Tambov

- 14 November 1917: Orel and Perm

- 15 November 1917: Pskov, Moscow, and Baku

- 27 November 1917: Tsaritsyn

- 1 December 1917: Mogilev

- 8 December 1917: Vyatka

- 10 December 1917: Kishinev

- 11 December 1917: Kaluga

- 14 December 1917: Novorossisk

- 15 December 1917: Kostroma

- 20 December 1917: Tula

- 24 December 1917: Kharkov (invasion of Ukraine by the Muravyov Red Guard forces, the establishment of Soviet Ukraine and hostilities in the region)

- 29 December 1917: Sevastopol (invasion of Crimea by the Red Guard forces, the establishment of the Taurida Soviet Socialist Republic)

- 4 January 1918: Penza

- 11 January 1918: Yekaterinoslav

- 17 January 1918: Petrozavodsk

- 19 January 1918: Poltava

- 22 January 1918: Zhitomir

- 26 January 1918: Simferopol

- 27 January 1918: Nikolayev

- 29 January 1918: (failed again in Kiev)

- 31 January 1918: Odessa and Orenburg (establishment of the Odessa Soviet Republic)

- 7 February 1918: Astrakhan

- 8 February 1918: Kiev and Vologda (defeat of the Ukrainian government)

- 17 February 1918: Arkhangelsk

- 25 February 1918: Novocherkassk

Russian Civil War

[edit]

Bolshevik-led attempts to gain power in other parts of the Russian Empire were largely successful in Russia proper—although the fighting in Moscow lasted for two weeks—but they were less successful in ethnically non-Russian parts of the Empire, which had been clamoring for independence since the February Revolution. For example, the Ukrainian Rada, which had declared autonomy on 23 June 1917, created the Ukrainian People's Republic on 20 November, which was supported by the Ukrainian Congress of Soviets. This led to an armed conflict with the Bolshevik government in Petrograd and, eventually, a Ukrainian declaration of independence from Russia on 25 January 1918.[65] In Estonia, two rival governments emerged: the Estonian Provincial Assembly, established in April 1917, proclaimed itself the supreme legal authority of Estonia on 28 November 1917 and issued the Declaration of Independence on 24 February 1918;[66] but Soviet Russia recognized the executive committee of the Soviets of Estonia as the legal authority in the province, although the Soviets in Estonia controlled only the capital and a few other major towns.[67]

After the success of the October Revolution transformed the Russian state into a soviet republic, a coalition of anti-Bolshevik groups attempted to unseat the new government in the Russian Civil War from 1918 to 1922. In an attempt to intervene in the civil war after the Bolsheviks' separate peace with the Central Powers (Germany and the Ottoman Empire), the Allied Powers (the United Kingdom, France, Italy, the United States, and Japan) occupied parts of the Soviet Union for over two years before finally withdrawing.[68] By the end of the violent civil war, Russia's economy and infrastructure were heavily damaged, and as many as 10 million perished during the war, mostly civilians.[69] Millions became White émigrés,[70] and the Russian famine of 1921–1922 claimed up to five million victims.[71] The United States did not recognize the new Russian government until 1933. The European powers recognized the Soviet Union in the early 1920s and began to engage in business with it after the New Economic Policy (NEP) was implemented.[citation needed]

Historiography

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Marxism–Leninism |

|---|

|

There have been few events where the political opinions of researchers have influenced their historical research as significantly as the October Revolution.[72] Generally, the historiography of the Revolution generally divides into three camps: Soviet-Marxist, Western-Totalitarian, and Revisionist.[73]

Soviet historiography

[edit]Soviet historiography of the October Revolution is intertwined with Soviet historical development. Many of the initial Soviet interpreters of the Revolution were themselves Bolshevik revolutionaries.[74] Bolshevik figures such as Anatoly Lunacharsky, Moisei Uritsky and Dmitry Manuilsky agreed that Lenin's influence on the Bolshevik party was decisive but the October insurrection was carried out according to Trotsky's, not to Lenin's plan.[75] After the initial wave of revolutionary narratives, Soviet historians worked within "narrow guidelines" defined by the Soviet government. The rigidity of interpretive possibilities reached its height under Stalin.[76]

Soviet historians of the Revolution interpreted the October Revolution as being about establishing the legitimacy of Marxist ideology and the Bolshevik government. To establish the accuracy of Marxist ideology, Soviet historians generally described the Revolution as the product of class struggle and that it was the supreme event in a world history governed by historical laws. The Bolshevik Party is placed at the center of the Revolution, as it exposes the errors of both the moderate Provisional Government and the spurious "socialist" Mensheviks in the Petrograd Soviet. Guided by Lenin's leadership and his firm grasp of scientific Marxist theory, the Party led the "logically predetermined" events of the October Revolution from beginning to end. The events were, according to these historians, logically predetermined because of the socio-economic development of Russia, where monopolistic industrial capitalism had alienated the masses. In this view, the Bolshevik party took the leading role in organizing these alienated industrial workers, and thereby established the construction of the first socialist state.[77]

Although Soviet historiography of the October Revolution stayed relatively constant until 1991, it did undergo some changes. Following Stalin's death, historians such as E. N. Burdzhalov and P. V. Volobuev published historical research that deviated significantly from the party line in refining the doctrine that the Bolshevik victory "was predetermined by the state of Russia's socio-economic development".[78] These historians, who constituted the "New Directions Group", posited that the complex nature of the October Revolution "could only be explained by a multi-causal analysis, not by recourse to the mono-causality of monopoly capitalism".[79] For them, the central actor is still the Bolshevik party, but this party triumphed "because it alone could solve the preponderance of 'general democratic' tasks the country faced" (such as the struggle for peace and the exploitation of landlords).[80]

During the late Soviet period, the opening of select Soviet archives during glasnost sparked innovative research that broke away from some aspects of Marxism–Leninism, though the key features of the orthodox Soviet view remained intact.[76]

Following the turn of the 21st century, some Soviet historians began to implement an "anthropological turn" in their historiographical analysis of the Russian Revolution. This method of analysis focuses on the average person's experience of day-to-day life during the revolution, and pulls the analytical focus away from larger events, notable revolutionaries, and overarching claims about party views.[81] In 2006, S. V. Iarov employed this methodology when he focused on citizen adjustment to the new Soviet system. Iarov explored the dwindling labor protests, evolving forms of debate, and varying forms of politicization as a result of the new Soviet rule from 1917 to 1920.[82] In 2010, O. S. Nagornaia took interest in the personal experiences of Russian prisoners-of-war taken by Germany, examining Russian soldiers and officers' ability to cooperate and implement varying degrees of autocracy despite being divided by class, political views, and race.[83] Other analyses following this "anthropological turn" have explored texts from soldiers and how they used personal war-experiences to further their political goals,[84] as well as how individual life-structure and psychology may have shaped major decisions in the civil war that followed the revolution.[85]

Western historiography

[edit]"Totalitarian" historians

[edit]During the Cold War, Western historiography of the October Revolution developed in direct response to the assertions of the Soviet view. As a result, Western historians exposed what they believed were flaws in the Soviet view, thereby undermining the Bolsheviks' original legitimacy, as well as the precepts of Marxism.[86] The view which originated in the early years of the Cold War became known as "traditionalist" and "totalitarian" as well as "Cold War" historians for relying on concepts and interpretations rooted in the early years of the Cold War and even in the sphere Russian White émigrés of the 1920s.[87][88]

These "traditionalist" historians described the revolution as the result of a chain of contingent accidents. Examples of these accidental and contingent factors they say precipitated the Revolution included World War I's timing, chance, and the poor leadership of Tsar Nicholas II as well as that of liberal and moderate socialists.[76] According to "totalitarian" historians, it was not popular support, but rather a manipulation of the masses, ruthlessness, and the party discipline of the Bolsheviks that enabled their triumph. For these historians, the Bolsheviks' defeat in the Constituent Assembly elections of November–December 1917 demonstrated popular opposition to the Bolsheviks' revolution, as did the scale and breadth of the Civil War.[89]

"Totalitarian" historians saw the organization of the Bolshevik party as totalitarian. Their interpretation of the October Revolution as a violent coup organized by a totalitarian party which aborted Russia's experiment in democracy.[90] Thus, Stalinist totalitarianism developed as a natural progression from Leninism and the Bolshevik party's tactics and organization.[91] To these historians, Soviet Russia in 1917 was as totalitarian as the USSR under Joseph Stalin in 1930s.[88] More to it, such historians have blamed Lenin and the Bolsheviks for inventing policies further implemented by totalitarian regimes of the 20th century, such as the Holocaust: for example, according to Richard Pipes, a prominent "totalitarian", "The Stalinist and Nazi holocausts" stemmed from Lenin's Red Terror and had "much greater decorum" than the latter.[92]

"Revisionist" historians

[edit]The 1960s-1970s saw a rise of a young historians who opposed the "totalitarian" historians and began challenging, revising and refuting the dominant and accepted conceptions, as well as criticizing the bias towards the USSR and the Left in general; they lacked a full-fledged doctrine or philosophy of history, but were distinguished as "revisionists"; in contrast with the focus of "totalitarian" historians on "politics" "from above" and on personalities of the leaders of political movements, "the one man", the revisionists have produced "history from below" and put attention on social history.[87][88] These historians tend to see a rupture between Stalinist totalitarianism and Leninism and refute the definition of the Revolution as a totalitarian coup carried out by a minority group; the 'revisionists' stress the genuinely 'popular' nature of the Bolshevik Revolution. According to Evan Mawdsley, "the 'revisionist' school had been dominant from the 1970s" in academic circles, and achieved "some success" in challenging the traditionalists;[88] however, they continued to be criticized by "totalitarians" who accused them of "Marxism" and failing to see the primary reason of political events, the personality of the leaders. During the rise of the "revisionists", "totalitarians" retained popularity and influence outside academic circles, especially in politics and public spheres of the United States, where they supported harder policies towards the USSR: for example, Zbigniew Brzezinski served as National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter, while Richard Pipes headed the CIA group Team B; after 1991, their views have found popularity not only in the West, but also in the former USSR.[32]

Effect of the dissolution of the Soviet Union on historical research

[edit]The dissolution of the Soviet Union affected historical interpretations of the October Revolution. Since 1991, increasing access to large amounts of Soviet archival materials has made it possible to re‑examine the October Revolution.[74] Though both Western and Russian historians now have access to many of these archives, the effect of the dissolution of the USSR can be seen most clearly in the work of the latter. While the disintegration essentially helped solidify the Western and Revisionist views, post-USSR Russian historians largely repudiated the former Soviet historical interpretation of the Revolution.[93] As Stephen Kotkin argues, 1991 prompted "a return to political history and the apparent resurrection of totalitarianism, the interpretive view that, in different ways...revisionists sought to bury".[74]

Legacy

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (November 2018) |

The October Revolution marks the inception of the first communist government in Russia, and thus the first large-scale and constitutionally ordained socialist state in world history. After this, the Russian Republic became the Russian SFSR, which later became the Soviet Union.

The October Revolution also made the ideology of communism influential on a global scale in the 20th century. Communist parties would start to form in many countries after 1917.

Ten Days That Shook the World, a book written by American journalist John Reed and first published in 1919, gives a firsthand exposition of the events. Reed died in 1920, shortly after the book was finished.

Dmitri Shostakovich wrote his Symphony No. 2 in B major, Op. 14, and subtitled it To October, for the 10th anniversary of the October Revolution. The choral finale of the work, "To October", is set to a text by Alexander Bezymensky, which praises Lenin and the revolution. The Symphony No. 2 was first performed on 5 November 1927 by the Leningrad Philharmonic Orchestra and the Academy Capella Choir under the direction of Nikolai Malko.

Sergei Eisenstein and Grigori Aleksandrov's film October: Ten Days That Shook the World, first released on 20 January 1928 in the USSR and on 2 November 1928 in New York City, describes and glorifies the revolution, having been commissioned to commemorate the event.

The Hollywood film, Reds, released in 1981 was based on Reed's account of the October Revolution and featured interviews with historical contemporaries from the period for the film.[94]

The term "Red October" (Красный Октябрь, Krasnyy Oktyabr) has been used to signify the October Revolution. "Red October" was given to a steel factory that was made notable by the Battle of Stalingrad,[95] a Moscow sweets factory that is well known in Russia, and a fictional Soviet submarine in both Tom Clancy's 1984 novel The Hunt for Red October and the 1990 film adaptation of the same name.

The date 7 November, the anniversary of the October Revolution according to the Gregorian Calendar, was the official national day of the Soviet Union from 1918 onward and still is a public holiday in Belarus and the breakaway territory of Transnistria. Communist parties both in and out of power celebrate 7 November as the date Marxist parties began to take power.

The Russian Revolution was perceived as a rupture with imperialism for various civil rights and decolonization struggles and providing a space for oppressed groups across the world. This was given further credence with the Soviet Union supporting many anti-colonial third world movements with financial funds against European colonial powers.[96]

See also

[edit]Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ 50,000 workers passed a resolution in favour of Bolshevik demand for transfer of power to the soviets.[1][2]

- ^ Russian: Октябрьская революция, romanized: Oktyabrskaya revolyutsiya, IPA: [ɐkˈtʲabrʲskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə].

- ^ Russian: Великая Октябрьская социалистическая революция, romanized: Velikaya Oktyabrskaya sotsialisticheskaya revolyutsiya, [vʲɪˈlʲikəjə ɐkˈtʲabrʲskəjə sətsɨəlʲɪˈsʲtʲitɕɪskəjə rʲɪvɐˈlʲutsɨjə]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Head, Michael (12 September 2007). Evgeny Pashukanis: A Critical Reappraisal. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-1353-0787-5.[page needed]

- ^ Shukman 1994, p. 21 The Workers: February–October 1917 .

- ^ "Russian Revolution". HISTORY. 9 November 2009. Archived from the original on 26 August 2023.

- ^ Figes 1996, Section 6: The October Revolution 1917.

- ^ a b "The Russian Revolution". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ "What Was the Bolshevik Revolution?". American Historical Association. Retrieved 1 June 2024.

- ^ "Russian Revolution, 1917". Holocaust Encyclopedia.

- ^ Shukman 1994, p. 343.

- ^ Bergman, Jay (2019). The French Revolutionary Tradition in Russian and Soviet Politics, Political Thought, and Culture. Oxford University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-1988-4270-5.

- ^ McMeekin, Sean (30 May 2017). The Russian Revolution: A New History. Basic. ISBN 978-0-4650-9497-4.[page needed]

- ^ "Russian Revolution – Causes, Timeline & Definition". www.history.com. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ "Russian Revolution | Definition, Causes, Summary, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- ^ Bunyan & Fisher 1934, p. 385.

- ^ Samaan, A.E. (2013). From a "Race of Masters" to a "Master Race": 1948 to 1848. A.E. Samaan. p. 346. ISBN 978-0-6157-4788-0. Retrieved 9 February 2017.

- ^ a b Steinberg, Mark (2017). The Russian Revolution 1905–1921. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 143–146. ISBN 978-0-1992-2762-4.

- ^ Mandel 1984.

- ^ Trotsky 1932, pp. 859–864.

- ^ Steinberg 2017, pp. 196–197.

- ^ Upton, Anthony F. (1980). The Finnish Revolution: 1917–1918. Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-4529-1239-4.

- ^ Steinberg 2017, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Pipes, Richard (1990). The Russian Revolution. Knopf Doubleday. p. 407. ISBN 978-0-3077-8857-3.

- ^ Kort, Michael (1993). The Soviet colossus: the rise and fall of the USSR. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-8733-2676-6.

- ^ Hickey, Michael C. (2010). Competing Voices from the Russian Revolution: Fighting Words: Fighting Words. ABC-CLIO. p. 559. ISBN 978-0-3133-8524-7.

- ^ Beckett 2007, p. 526

- ^ Pipes 1997, p. 51: "There is no evidence of a Kornilov plot, but there is plenty of evidence of Kerensky's duplicity."

- ^ Service 1998, p. 54

- ^ "Провозглашена Российская республика". Президентская библиотека имени Б.Н. Ельцина (in Russian). Retrieved 6 November 2021.

- ^ "Central Committee Meeting". www.marxists.org. 10 October 1917.

- ^ Steinberg, Mark (2001). Voices of the Revolution, 1917. Binghamton, New York: Yale University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-3001-0169-0. OL 9360660M.

- ^ Cohen, Stephen (1980). Bukharin and the Bolshevik Revolution: A Political Biography 1888–1938. London: Oxford University Press. p. 46.

- ^ "1917 – La Revolution Russe". Arte TV. 16 September 2007. Archived from the original on 1 February 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ^ a b c d Suny, Ronald Grigor (2011). The Soviet Experiment. Oxford University Press. pp. 63–67.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rabinowitch 2004, pp. 273–305

- ^ Bard College: Experimental Humanities and Eurasian Studies. "From Empire To Republic: October 24 – November 1, 1917". Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (1962). The Stalin School of Falsification. Pioneer Publishers. p. 12.

- ^ a b Beckett 2007, p. 528

- ^ Rabinowitch 2004

- ^ Lynch, Michael (2015). Reaction and revolution : Russia 1894–1924 (4th ed.). London: Hodder Education. ISBN 978-1-4718-3856-9. OCLC 908064756.

- ^ Raul Edward Chao (2016). Damn the Revolution!. Washington DC, London, Sydney: Dupont Circle Editions. p. 191.

- ^ "1917 Free History". Yandex Publishing. Archived from the original on 8 November 2017. Retrieved 8 November 2017.

- ^ "ВОЕННАЯ ЛИТЕРАТУРА – [ Мемуары ] – Дыбенко П.Е. Из недр царского флота к Великому Октябрю". militera.lib.ru (in Russian).

- ^ Bryant, Louise (1918). Six Red Months in Russia: An Observer's Account of Russia Before and During the Proletarian Dictatorship. New York: George H. Doran Company. pp. 60–61. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- ^ Schell, Jonathan (2003). "The Mass Minority in Action: France and Russia'" (PDF). The Unconquerable World. Power, nonviolence and the will of the people. London: Penguin. pp. 167–185. ISBN 9780805044577. OL 36779W.

- ^ (See a first-hand account by British General Alfred Knox.)

- ^ Eisenstein, Sergei M.; Aleksandrov, Grigori (1928). October: Ten Days That Shook the World (Motion picture). First National Pictures.

- ^ Argumenty I Fakty newspaper

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (2 January 2022). "Stalin, Falsifier in Chief: E. H. Carr and the Perils of Historical Research Introduction". Revolutionary Russia. 35 (1): 11–14. doi:10.1080/09546545.2022.2065740. ISSN 0954-6545.

- ^ Bailey, Sydney D. (1955). "Stalin's Falsification of History: The Case of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty". The Russian Review. 14 (1): 24–35. doi:10.2307/126074. ISSN 0036-0341. JSTOR 126074.

- ^ Trotsky, Leon (13 January 2019) [1932]. Shachtman, Max (ed.). The Stalin School of Falsification. Pickle Partners Publishing. pp. vii-89. ISBN 978-1-7891-2348-7.

- ^ "The Constituent Assembly". jewhistory.ort.spb.ru.

- ^ Pipes, Richard (1990). The Russian Revolution. New York : Knopf. p. 499. ISBN 978-0-3945-0241-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: publisher location (link) - ^ Deutscher, Isaac (1954). The prophet armed: Trotsky, 1879-1921. New York, Oxford University Press. p. 325.

- ^ Sukhanov, Nikolai Nikolaevich (14 July 2014). The Russian Revolution 1917: A Personal Record by N.N. Sukhanov. Princeton University Press. p. 266. ISBN 978-1-4008-5710-4.

- ^ Service, Robert (1998). A history of twentieth-century Russia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-6744-0347-9 p. 65

- ^ Reed 1997, p. 217

- ^ Steinberg 2001, pp. 251.

- ^ Reed 1997, p. 369

- ^ Reed 1997, p. 410

- ^ Reed 1997, p. 565

- ^ a b Steinberg 2001, p. 257

- ^ Llewellyn, Jennifer; Rae, John; Thompson, Steve (2014). "The Constituent Assembly". Alpha History. Retrieved 7 March 2022.

- ^ Figes 1996.

- ^ Pipes, Richard (2011). The Russian Revolution. Knopf Doubleday. p. 789. ISBN 978-0-3077-8857-3.

- ^ Kline, George L. (1992). "In Defence of Terrorism". In Brotherstone, Terence; Dukes, Paul (eds.). The Trotsky reappraisal. Translated by Drummond, Andrew; Pearce, Brian; Brine, J. J. Edinburgh University Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7486-0317-6.

- ^ See Encyclopedia of Ukraine online

- ^ Miljan, Toivo (2015). Historical Dictionary of Estonia." Historical Dictionary of Estonia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-8108-7513-5.

- ^ Raun, Toivo U. (2002). "7. The Emergence of Estonian Independence 1917–1920". Estonia and the Estonians. Hoover Inst. Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-8179-2853-7.

- ^ Ward, John (2004). With the "Die-Hards" in Siberia. Dodo Press. p. 91. ISBN 1-4099-0680-9.

- ^ "Russian Civil War – Casualties and consequences of the war". Encyclopedia Britannica. 29 May 2024.

- ^ Schaufuss, Tatiana (May 1939). "The White Russian Refugees". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 203. SAGE Publishing: 45–54. doi:10.1177/000271623920300106. JSTOR 1021884. S2CID 143704019.

- ^ Haller, Francis (8 December 2003). "Famine in Russia: the hidden horrors of 1921". Le Temps. International Committee of the Red Cross.

- ^ Acton 1997, p. 5

- ^ Acton 1997, pp. 5–7

- ^ a b c Kotkin, Stephen (1998). "1991 and the Russian Revolution: Sources, Conceptual Categories, Analytical Frameworks". The Journal of Modern History. 70 (2). University of Chicago Press: 384–425. doi:10.1086/235073. ISSN 0022-2801. S2CID 145291237.

- ^ Deutscher, Isaac (5 January 2015). The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky. Verso Books. p. 1283. ISBN 978-1-7816-8721-5.

- ^ a b c Acton 1997, p. 7.

- ^ Acton 1997, p. 8.

- ^ Litvin, Alter (2001). Writing History in Twentieth-Century Russia. New York: Palgrave. pp. 49–50.

- ^ Markwick, Roger (2001). Rewriting History in Soviet Russia: The Politics of Revisionist Historiography. New York: Palgrave. p. 97.

- ^ Markwick 2001, p. 102.

- ^ Smith, S. A. (2015). "The historiography of the Russian Revolution 100 Years On". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 16 (4): 733–749. doi:10.1353/kri.2015.0065. S2CID 145202617.

- ^ Iarov, S.V. (2006). "Konformizm v Sovetskoi Rossii: Petrograd, 1917–20". Evropeiskii Dom (in Russian).

- ^ Nagornaia, O. S. (2010). "Drugoi voennyi opyt: Rossiiskie voennoplennye Pervoi mirovoi voiny v Germanii (1914–1922)". Novyi Khronograf (in Russian).

- ^ Morozova, O. M. (2010). "Dva akta dreamy: Boevoe proshloe I poslevoennaia povsednevnost ' veteran grazhdanskoi voiny". Rostov-on-Don: Iuzhnyi Nauchnyi Tsentr Rossiiskoi Akademii Nauk (in Russian).

- ^ Morozova, O. M. (2007). "Antropologiia grazhdanskoi voiny". Rostov-on-Don: Iuzhnyi Nauchnyi Tsentr RAN (in Russian).

- ^ Acton 1997, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Acton 1997, pp. 4–13.

- ^ a b c d Mawdsley, Evan (2011). The Russian Civil War. Birlinn. ISBN 9780857901231.

- ^ Acton 1997, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Francis, Norbert. "Revolution in Russia and China: 100 Years" (PDF). International Journal of Russian Studies. 6 (July 2017): 130–143.

- ^ Hanson, Stephen E. (1997). Time and Revolution: Marxism and the Design of Soviet Institutions. University of North Carolina Press. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-8078-4615-5.

- ^ Suny, Ronald Grigor (2017). Red Flag Unfurled: History, Historians and the Russian Revolution. Verso Books.

- ^ Litvin 2001, p. 47.

- ^ Berger, Hanno (20 September 2022). Thinking Revolution Through Film: On Audiovisual Stagings of Political Change. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 123–130. ISBN 978-3-1107-5470-4.

- ^ Ivanov, Mikhail (2007). Survival Russian. Montpelier, VT: Russian Life Books. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-8801-0056-1. OCLC 191856309.

- ^ Thorpe, Charles (28 February 2022). Sociology in Post-Normal Times. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-7936-2598-4.

Sources

[edit]- Acton, Edward (1997). Critical Companion to the Russian Revolution.

- Beckett, Ian F. W. (2007). The Great war (2 ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-1252-8.

- Bunyan, James; Fisher, Harold Henry (1934). The Bolshevik Revolution, 1917–1918: Documents and Materials. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. OCLC 253483096.

- Figes, Orlando (1996). A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891–1924. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-8050-9131-1.

- Mandel, David (1984). The Petrograd Workers and the Soviet Seizure of Power :From the July Days, 1917 to July 1918. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-3126-0395-3. OCLC 9682585. OL 3171762M.

- Pipes, Richard (1997). Three "whys" of the Russian Revolution. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0-6797-7646-8.

- Rabinowitch, Alexander (2004). The Bolsheviks Come to Power: The Revolution of 1917 in Petrograd. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-2268-1.

- Reed, John (1997) [1919]. Ten Days that Shook the World. New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Service, Robert (1998). A history of twentieth-century Russia. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-6744-0347-9.

- Shukman, Harold, ed. (1994). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of the Russian Revolution. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-6311-9525-2.

- Trotsky, Leon (1932) [1930]. The History of the Russian Revolution. Vol. III: The Triumph of the Soviets. Translated by Eastman, Max. London: Gollancz. OCLC 605191028.

- Wade, Rex A. "The Revolution at One Hundred: Issues and Trends in the English Language Historiography of the Russian Revolution of 1917." Journal of Modern Russian History and Historiography 9.1 (2016): 9–38. doi:10.1163/22102388-00900003

Further reading

[edit]- Ascher, Abraham (2014). The Russian Revolution: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Publications.

- Bone, Ann (trans.) (1974). The Bolsheviks and the October Revolution: Central Committee Minutes of the Russian Social-Democratic Labour Party (Bolsheviks) August 1917 – February 1918. Pluto Press. ISBN 0-9028-1854-6.

- Chamberlin, William Henry (1935). The Russian Revolution. Vol. I: 1917–1918: From the Overthrow of the Tsar to the Assumption of Power by the Bolsheviks. online vol 1; also online vol 2

- Guerman, Mikhail (1979). Art of the October Revolution.

- Kollontai, Alexandra (1971). "The Years of Revolution". The Autobiography of a Sexually Emancipated Communist Woman. New York: Herder and Herder. OCLC 577690073.

- Krupskaya, Nadezhda (1930). "The October Days". Reminiscences of Lenin. Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House. OCLC 847091253.

- Luxemburg, Rosa (1940) [1918]. The Russian Revolution. Translated by Bertram Wolfe. New York City: Workers Age. OCLC 579589928.

- Radek, Karl (1995) [First published 1922 as "Wege der Russischen Revolution"]. "The Paths of the Russian Revolution". In Bukharin, Nikolai; Richardson, Al (eds.). In Defence of the Russian Revolution: A Selection of Bolshevik Writings, 1917–1923. London: Porcupine Press. pp. 35–75. ISBN 1-8994-3801-7. OCLC 33294798.

- Read, Christopher (1996). From Tsars to Soviets.

- Serge, Victor (1972) [1930]. Year One of the Russian Revolution. London: Penguin Press. OCLC 15612072.

- Swain, Geoffrey (2014). Trotsky and the Russian Revolution. Routledge.

- Trotsky, Leon (1930). "XXVI: From July to October". My Life. London: Thornton Butterworth. OCLC 181719733.

External links

[edit]- free books on Russian Revolution

- Read, Christopher: Revolutions (Russian Empire), in: 1914–1918 online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Peeling, Siobhan: July Crisis 1917 (Russian Empire), in: 1914–1918 online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- The October Revolution Archive

- Let History Judge Russia's Revolutions, commentary by Roy Medvedev, Project Syndicate, 2007

- October Revolution and Logic of History

- Maps of Europe Archived 16 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine and Russia Archived 21 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine at time of October Revolution at omniatlas.com

- How the Bolshevik party elite crushed the democratically elected workers and popular councils – soviets – and established totalitarian state capitalism.

October Revolution

View on GrokipediaTerminology and Interpretations

Names and Etymological Origins

The October Revolution derives its name from the principal events of the Bolshevik seizure of power, which occurred on 25 October 1917 according to the Julian calendar then prevailing in Russia. This Julian dating corresponded to 7 November 1917 in the Gregorian calendar, the solar-based system adopted earlier in Western Europe to correct the Julian calendar's gradual drift from astronomical seasons, but Russia retained the Julian system until February 1918 due to ecclesiastical and administrative inertia. The persistence of the "October" designation post-calendar reform reflects Bolshevik efforts to commemorate the event in terms of its original local chronology, embedding it in revolutionary mythology despite the shift to Gregorian reckoning.[6] In Russian, the event is termed Oktyabr'skaya revolyutsiya (Октябрьская революция), literally "October Revolution," with oktyabr' stemming from the Latin octō, denoting the eighth month in the ancient Roman calendar (prior to the Julian reform's addition of January and February).[7] Soviet official nomenclature expanded this to Velikaya Oktyabr'skaya sotsialisticheskaya revolyutsiya (Великая Октябрьская социалистическая революция), or "Great October Socialist Revolution," a formulation codified in party doctrine and state propaganda to underscore the proletarian, socialist triumph over bourgeois provisional rule, first prominently invoked in Lenin's writings and congress declarations shortly after the events.[7] Other contemporaneous and historiographical appellations include "Bolshevik Revolution," emphasizing the vanguard role of Lenin's Bolshevik faction within the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, and "Red October," evoking the symbolic red banners of socialist insurgents amid urban unrest.[8] These variants arose in both émigré critiques and Western analyses, often contrasting with Soviet glorification by framing the upheaval as a factional putsch rather than a mass uprising, though the calendrical "October" root remains consistent across usages.[9]Debate: Revolution vs. Coup d'État

The debate over whether the events of October 1917 (November 7 Gregorian) constituted a genuine revolution or a coup d'état centers on the scale of popular participation, the Bolsheviks' mandate, and the mechanics of power seizure. Proponents of the coup interpretation argue that the Bolshevik takeover was executed by a relatively small, organized force without widespread national uprising or electoral legitimacy, resembling a palace intrigue more than a mass revolt.[2][10] In contrast, defenders frame it as a revolutionary culmination of class conflict, driven by worker and soldier discontent with the Provisional Government, though this view often relies on Bolshevik-controlled soviet resolutions rather than broader empirical measures of support.[11] Key evidence for the coup characterization includes the limited scope of action: the seizure was confined primarily to Petrograd, involving an estimated 20,000–25,000 Red Guards—factory militias loyal to the Bolsheviks—who targeted key sites like bridges, telegraph offices, and the Winter Palace with minimal opposition and few casualties (under 10 reported deaths).[6] This contrasts sharply with the February Revolution's spontaneous involvement of hundreds of thousands across multiple cities. Historian Richard Pipes described it as a "coup d'état" orchestrated by Lenin and the Bolshevik Central Committee, bypassing democratic processes amid the Provisional Government's weakness rather than reflecting irreducible popular will.[10] The Bolsheviks' lack of majority backing is underscored by the November–December 1917 elections to the Constituent Assembly, Russia's first nationwide vote by universal suffrage, where they secured only about 24% of the vote (roughly 9.8 million votes) and 175 of 715 seats, trailing the Socialist Revolutionaries' 38–40% (16 million votes) and 370+ seats.[12][13] Lenin dissolved the Assembly by force on January 6, 1918 (January 18 Gregorian), after it convened with an SR majority, further evidencing prioritization of party control over plebiscitary validation.[5] Arguments portraying it as a revolution emphasize Bolshevik influence in Petrograd's soviets and garrisons, where anti-war sentiment and "All Power to the Soviets" slogans resonated among urban proletarians and mutinous soldiers, enabling the Military Revolutionary Committee's de facto control before the putsch.[9] Some Marxist historians, like Ernest Mandel, contend it initiated a social revolution by empowering the proletariat against bourgeois provisional rule, citing subsequent land redistribution and factory committees as causal extensions of worker agency.[11] However, these claims falter under scrutiny: Bolshevik urban strength (e.g., 51–63% in some northern districts) did not translate nationally, and soviet "support" often reflected manipulated voting in Bolshevik-dominated bodies rather than organic consensus, as peasant majorities favored land-focused SR policies.[14] Soviet-era historiography amplified the revolutionary narrative to legitimize one-party rule, while post-1991 reevaluations in Russia increasingly term it a "coup" due to its top-down execution and suppression of rivals.[15] Ultimately, the event's coup-like traits—elite orchestration, localized force, and rejection of electoral outcomes—prevailed over revolutionary hallmarks like diffuse mass mobilization, enabling Bolshevik consolidation but sowing seeds of civil war through alienated majorities. This interpretation aligns with causal analysis: the Provisional Government's failures (war continuation, delayed reforms) created opportunity, but Bolshevik success hinged on vanguard seizure, not inexorable popular tide.[16][17]Pre-Revolutionary Context

Tsarist Russia's Structural Weaknesses

Russia's economy remained overwhelmingly agrarian into the early 20th century, with roughly 80 percent of the population consisting of peasants tied to subsistence farming on inefficient communal lands (obshchina), which discouraged individual investment and technological improvements. [18] [19] This structure perpetuated chronic food shortages, land scarcity post-1861 emancipation, and vulnerability to poor harvests, as peasants faced high redemption payments, taxes, and limited access to markets. [20] [21] Industrial development, spurred by state-led policies under Sergei Witte from the 1890s, achieved some growth in sectors like railways and coal but was uneven, regionally concentrated (e.g., Ukraine and the Urals), and heavily dependent on foreign capital and expertise, leaving the broader economy technologically backward relative to Western Europe. [22] [23] By 1913, manufacturing contributed only about 20 percent to GDP, with low productivity due to unskilled labor, obsolete machinery, and inadequate infrastructure, fostering urban worker discontent amid rapid proletarianization without commensurate wage gains or social supports. [19] [24] The autocratic governance under Tsar Nicholas II exacerbated these issues through a bloated, corrupt bureaucracy where officials, often poorly educated and underpaid, routinely engaged in bribery and favoritism, undermining policy implementation and fiscal management. [25] [26] State finances strained by prior defeats (e.g., Crimean War, 1853–1856; Russo-Japanese War, 1904–1905) and high military spending left little for reforms, while the nobility's privileges stifled merit-based administration. [19] [27] Socially, low literacy—estimated at around 40 percent overall by 1913, with rural rates far lower—hindered human capital development and perpetuated inequality, as the elite captured most gains from limited growth while peasants and workers endured overpopulation and minimal mobility. [28] [29] The military, though vast (over 1.4 million standing troops by 1914), suffered structural flaws including outdated tactics, supply chain deficiencies, and officer cronyism, rendering it ill-equipped for modern warfare despite numerical advantages. [30] [31] These interlocking weaknesses—economic stagnation, administrative rot, and institutional rigidity—eroded regime legitimacy and amplified vulnerabilities to internal unrest. [32] [33]Impact of World War I

Russia entered World War I on August 1, 1914, following its mobilization on July 30 in support of Serbia against Austria-Hungary, aligning with the Entente Powers against the Central Powers.[34] Early campaigns proved disastrous, exemplified by the defeat at the Battle of Tannenberg in late August 1914, where the Russian Second Army suffered heavy losses due to poor coordination, inadequate intelligence, and supply shortages, resulting in the capture of over 90,000 prisoners and the death or wounding of approximately 250,000 soldiers.[35] Despite some successes, such as the Brusilov Offensive in June-September 1916, which inflicted over 1 million casualties on Austro-Hungarian forces but cost Russia around 1 million of its own troops, the overall military effort exposed systemic weaknesses including obsolete equipment, insufficient artillery, and incompetent leadership, leading to repeated retreats and the "Great Retreat" of 1915.[34] By mid-1916, Russian casualties exceeded 5.3 million, including over 2 million dead or permanently disabled, surpassing those of any other belligerent and eroding army morale through desertions, mutinies, and widespread disillusionment with Tsar Nicholas II's personal command of the front from September 1915.[36] These losses, compounded by equipment shortages—such as soldiers advancing without rifles or sufficient ammunition—fostered anti-war sentiment, particularly among peasants conscripted en masse, who comprised the bulk of the infantry and faced attritional warfare without corresponding territorial gains.[35] The Bolsheviks capitalized on this war weariness, promoting slogans like "Peace, Land, and Bread" to contrast with the Provisional Government's continuation of the conflict after the February Revolution.[37] On the home front, the war triggered economic collapse, with industrial production disrupted by resource diversion to the military, leading to hyperinflation that devalued the ruble by over 300% between 1914 and 1917 and caused real wages to plummet by half.[38] Agrarian output declined due to labor shortages from mobilization—over 15 million men conscripted—and disrupted rail transport, resulting in chronic food deficits; by 1916, urban centers like Petrograd experienced severe bread shortages and queues, exacerbated by hoarding and speculation amid fixed prices.[39] Fuel and coal scarcities further paralyzed factories and heating, sparking strikes and riots that undermined civilian support for the regime, as inflation rendered wartime promises of prosperity hollow and highlighted the Tsarist government's logistical failures.[34] These strains collectively delegitimized the autocracy, as military defeats and domestic privation fueled radicalization; the army's breakdown provided Bolshevik forces with sympathetic soldiers during the October events, while economic chaos enabled Lenin's return and agitation against the war, directly precipitating the revolution by eroding the Provisional Government's authority to prosecute the conflict.[35][37]February Revolution and Provisional Government

The February Revolution erupted in Petrograd on February 23, 1917 (Julian calendar), triggered by mass strikes over food shortages, with around 130,000 workers from 50 factories walking out on the first day, primarily women textile operatives protesting on International Women's Day.[40] Demonstrations demanding "Bread and Peace" rapidly swelled, fueled by wartime inflation that had halved real wages since 1914 and transport breakdowns leaving granaries full in rural areas while cities starved.[3] By February 24, strikers numbered over 200,000, including metalworkers from the Putilov plant, as crowds looted shops and clashed with police, who killed about 40 protesters.[41] [3] Government troops initially fired on crowds on February 25, killing dozens more, but exhaustion from 2.5 million casualties in World War I eroded discipline, prompting Volynsky Regiment mutineers to shoot their officers and join demonstrators by evening.[3] On February 26, further mutinies spread across the Petrograd garrison of 160,000 soldiers, with park artillery and Pavlovsk regiments defecting, enabling revolutionaries to storm jails and release 72,000 prisoners, including socialists.[41] [3] Tsar Nicholas II, en route from the front, ordered suppression but faced ministerial collapse; isolated at Pskov, he abdicated on March 2 (Julian; March 15 Gregorian) for himself and his hemophiliac son Alexei, initially naming brother Grand Duke Michael successor, who renounced the throne the next day amid mob threats, terminating 304 years of Romanov rule without formal trial or violence against the imperial family at that stage. [3] The Provisional Government coalesced on March 1 from the Duma's Temporary Committee, chaired by liberal Octobrist Mikhail Rodzianko, excluding socialists initially to maintain order; Prince Georgy Lvov served as premier, with Foreign Minister Pavel Milyukov (Kadets) and War Minister Alexander Guchkov (Octobrists) dominating, pledging civil liberties, amnesty for political exiles, and elections for a Constituent Assembly by November while upholding Russia's war alliances and debt obligations.[42] Concurrently, the Petrograd Soviet formed on March 1 with 3,000 delegates from factories and mutinous units, dominated by Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries, issuing Order No. 1 on March 3 that democratized army committees, elected officers, and prioritized soviet over government directives in military matters, inaugurating "dual power" where the bourgeoisie-led executive coexisted uneasily with proletarian councils.[41] [42] The government's policies prioritized stabilizing the war front—reinforcing the Brusilov Offensive's remnants despite 1.5 million desertions—and deferred radical reforms like land seizure, arguing such changes awaited constituent deliberation to avoid anarchy, though this alienated peasants holding 90% of arable land under noble titles and workers facing 300% price hikes. [42] Milyukov's April 1917 note reaffirming annexations provoked the "April Days" crisis, forcing socialist inclusions in a First Coalition under Lvov, then Alexander Kerensky after Lvov's July resignation, but persistent food requisitions and offensive failures (e.g., June 1917 Kerensky Offensive yielding 60,000 casualties) eroded its legitimacy, empowering Bolshevik critiques of bourgeois provisionalism.[42] [41]Bolshevik Ascendancy

Dual Power Dynamics